3.1. Algorithm: General Framework for Parameter Space Exploration and Categorization

The suggested framework is extensible since it is model-independent. It is also meant to be used on a nonlinear dynamical system through the redefinition of the governing equations and parameter ranges; that is, each step, such as the definition of parameters and their classification, is a standalone module. The algorithm enables simulations to be parallelized across multiple cores or nodes, enabling an effective exploration of higher-dimensional parameter spaces of interest. As an illustration, the same framework can be used with the Rossler system as well as with other systems, without making any changes to the basic framework. This scalability to higher-dimensional systems and larger networks is guaranteed by this modular design and computational flexibility. The framework is designed as a sequence of systematic steps that mutually allow for efficient exploration of parameters and categorization of stability, beginning with the definition of parameter space and leading to the classification and storage of results.

The methodology starts with the definition of the parameter space in which an analysis will be performed. This includes specifying the ranges of all system parameters , the choice of appropriate initial conditions, and the choice of sampling. The sampling plan or step size is selected carefully to trade off between computational feasibility and the resolution required to resolve key transitions in the system behavior.

After defining the parameter space, the external control variables, including the strength of the coupling , are prescribed. The data structures at this level are also ready to hold the results of simulations and related classifications. It is an organization that makes all results available for analysis later and prevents redundancy in the iterative process.

The fundamental structure of the framework is a systematic exploration loop through a parameter space that is automated. Each control variable is tested in each entry of all triplets of parameters . The simulation is either a combination of the system trajectories or a calculation of the Jacobian at every point, and the resultant eigenvalue or trajectory data are saved to be used later. This removes the issue of individual codes or the manual execution of individual cases.

Once the data are collected, they undergo a classification scheme in order to differentiate the various types of system behavior. Statistical parameters such as growth, decay, and periodicity are investigated when these are based on trajectories. Alternatively, using the eigenvalue analysis, the Jacobian matrix is obtained, and its eigenvalues are evaluated to obtain the type of stability of the system. All cases are then defined by the dynamics they exhibit; that is, divergent, non-divergent, periodic, or certain types of stability, namely, and .

All parameter sets, initial conditions, and their corresponding categories are stored in well-formatted forms to facilitate reproducibility and scalability. It is possible to export the results to CSV files or other standard storage systems, and thus efficiently retrieve, share, and process further with additional statistics without repeating the simulations.

Lastly, the results are categorized and visualized to provide clear information on the system’s behavior in the parameter space. Scatter plots, distribution charts, and coordinate plots are used to draw attention to trends and changes in dynamical regimes. These visualizations help us to understand the complicated parameters, initial conditions, and relationships between the outcomes of the system.

3.2. Application

In this paper, a brain-inspired dynamical system is a term used to describe a mathematical model that recapitulates important dynamic properties of a brain activity, including oscillations, synchronization, and chaotic transitions. This study was based on the Rossler system, which is chaotic in nature. It was initially generalized to a 360-node network with each node modeling an individual Rossler oscillator that interacts with the others via coupling terms. Such a network configuration allowed for the achievement of a wide range of complex collective behaviors, including synchronization and phase correlations among nodes. However, here in the current study, the emphasis is on one node of the system to examine the behavior of the node itself and to obtain the local properties of the system in the context of the network.

The given case study is devoted to the Rossler system as one of the representatives of the nonlinear ODEs, due to the wide variety of dynamic behaviors that can be observed in the system; thus, it serves as a suitable test case for the proposed framework in the exploration and classification of the parameter space. The selection of one system was aimed at providing a strong and descriptive illustration of the procedure and its working process. However, the framework itself is model-independent and can be applied directly to other nonlinear dynamical systems, e.g., the Lorenz, Chen, or Hindmarsh–Rose models, by merely redefining the governing equations and parameter ranges. This flexibility is used to ensure that the approach is always general and applicable in real life within different fields of science and engineering. The dynamical system taken into account in this work is provided by the following set of corresponding nonlinear differential equations [

22].

The variables , , and represent the dynamic states of the i-th unit in the network and evolve over time. This set of control coefficients incorporates the local control coefficients, where the self-feedback of is provided by , a constant external feed to is provided by , and the decay rate of is provided by . An interaction between the components and has a nonlinear term in the equation. The diffusion conditions are represented in summation terms that indicate the interconnectivity of the nodes. The products , , and indicate the intensity of association between the nodes i and j. Using a combination of these, we can obtain a very highly flexible system that can display many different behaviors, and all this depends on the parameter values, as well as the strengths of the interactions. The dynamical system studied in this paper originates from a brain-inspired nonlinear circuit model, and it is constructed from a number of locally interconnected nonlinear ordinary differential equations that model the time-dependent behavior of three state variables , , and at node i. Such variables are states of electricity in a simplified circuit model of a neural unit using circuit analogs, capacitors, and resistors. The system exhibits a wide range of dynamics, including local feedback, nonlinearity, and inter-node coupling.

We examine a nonlinear dynamical system represented as a network of interconnected components. Each unit of the network is described by three state variables that capture its behavior under different conditions. The internal parameters of the system, , , and , are systematically varied over a wide range to explore the response of the system across diverse parameter settings. The strength of the interaction controls the coupling between the units, indicating the level of influence they exert on each other. Three coupling strengths are considered: 0% (no coupling), 10% (moderate coupling), and 20% (strong coupling) to study how different levels of interaction affect the overall dynamics of the system.

The external nodes have fixed values, and for the purpose of studying the internal behavior, we set , , and . These act as constant injections or background inputs from neighboring areas and, in effect, create a closed system in which the dynamics of the local nodes can be observed and classified.

We also performed a systematic sweep of initial conditions to enable a finer analysis of the system’s sensitivity to initial conditions, as well as the resulting dynamical behaviors. Specifically, the initial conditions of the form

,

, and

are varied using a discrete grid with a step of 0.3 in the domain [−0.2, 0.2]. In order to study the behavior of the system under any of these initial conditions, we introduce an automatic structure of simulations, where all the possible consistent dynamical trajectories and their indexed results can be constructed during a single run. This also eliminates the necessity of handling each initial condition separately with manual analysis and allows all of the relevant parametric behavior to be plotted simultaneously, saving significantly on computing and visualization expenses, with much of the systematic exploration preserved. A direct choice of the parameter ranges and initial conditions was made to be consistent with the original system specification in the reference model [

22]. The parameters

,

, and

used in that model are positive control coefficients that should act within a reasonably positive range. Therefore, the range

was adopted to encompass the entire meaningful operating space, as well as to permit systematic exploration. Similarly, the reference model specifies that the starting conditions applied in its simulations were randomly chosen within the interval [−0.2, 0.2] for each state variable and were maintained the same in the current work. On the whole, these options allow for maintaining the parameters of the original formulation in balance, in addition to enabling a complete exploration of the dynamics of the system.

Table 2 illustrates the ranges and fixed values of the parameters involved in the analysis of the dynamical system with different coupling strengths

, which set the shape parameters.

Table 3 provides the initial conditions used in the simulation, including the range and step size of each state variable

.

In order to investigate the stability behavior of the nonlinear dynamical system, we perform an eigenvalue analysis by computing the Jacobian matrix at the chosen initial conditions for each combination of parameters. The system is linearized around the sampled initial states instead of determining the explicit equilibrium point, and the local response of the system to small disturbances at these points is determined. That way, we obtain the information on whether the local flow around the initial state is divergent, non-divergent, or periodic, which aids in categorizing the behavior in the parameter space. Once the Jacobian J has been calculated at every sampled point, the characteristic equation is solved to extract the eigenvalues, and then these eigenvalues are used to classify the local linear behavior of the system. In a three-variable system whose state variables are

, the Jacobian matrix will acquire the general form:

Once the Jacobian is calculated, we find the eigenvalues using the characteristic polynomial, which is obtained through the following determinant equation:

where

represents the eigenvalues and

I is the identity matrix. When the real parts of all the eigenvalues are negative, the system is locally stable; if there is one eigenvalue with a positive real part, the system is unstable. Imaginary eigenvalues completely solve a problem that is oscillatory or periodic. Such an eigenvalue-based classification systematizes and makes rigorous the analysis of the dynamic behavior of the system across parameter regimes.

3.2.1. Case 1:

When there is no coupling of nodes, the coefficient

assumes a value of zero. This disconnects the system node from the network, and only its internal dynamics are governed by the parameters

. The resulting system is as follows:

In order to analyze the local behavior of this system in the parameter space, a Jacobian matrix is computed as such at the chosen initial conditions. The eigenvalues of this Jacobian determine whether the local flow around those locations is rotational, contracting, or divergent. The classification of eigenvalues allows us to plot the various types of responses within the range of parameters being investigated.

3.2.2. Case 2:

In this case, the coupling is moderate, and

. The internal parameters belong to the interval

. The external node values are assigned as

,

, and

. Replacing them in the system, we obtain the following:

The stability behavior of this case is also evaluated in the same way. The Jacobian is evaluated at the selected initial states, and the eigenvalues obtained characterize the local dynamics of each simulation parameter combination.

3.2.3. Case 3:

Here, the coupling effect is considered stronger with

. The internal parameters are now in the range [0, 6], and the external parameters are set to the same values as before:

,

, and

. The results of substitution are as follows:

At higher coupling strengths, the obtained expressions are discussed using the same Jacobian-based procedure employed throughout this paper. The local eigenvalues that are calculated in the sampled states show how strong the coupling is and how it shifts the immediate tendencies of the system.

3.3. Systematic Parameter Space Categorization

A systematic investigation of how system responses change as important parameters and initial conditions change is necessary to comprehend the dynamic behavior of nonlinear systems. In order to thoroughly map the dynamics of a brain-inspired nonlinear system, we use a methodical parameter space classification approach in this study. We are able to capture a large range of potential system behaviors by building a grid in a three-dimensional parameter space, specified by , , and , each of which ranges from 0 to 6. Critical transitions and areas of qualitative change in system dynamics, such as bifurcations, stability loss, and oscillation beginning, can be detected using this grid-based method. To demonstrate the sensitivity of the system to initial conditions, we chose three representative initial states from a large number of conditions , , and . These have been selected as examples to show the range of behavior levels. Two distinct methodologies are employed within this framework to categorize system behavior.

Analysis of Statistical Behavior: This method assesses the system time-series trajectories to identify if the behavior is periodic, non-divergent, or diverging. It provides a global view of the long-term behavior of the system by concentrating on how it changes over time under various circumstances. This approach demonstrates how changes to the initial conditions or parameters affect the trajectory results.

Eigenvalue Classification: The Jacobian matrix is calculated at the local behavior of the system under the chosen initial conditions. The eigenvalues of this Jacobian explain the response of the system to small disturbances around the sampled states. Having sorted the eigenvalues into real, complex, positive, negative, or zero, we can deduce the existence of tendencies in the general behavior of the parameter space, e.g., divergence, non-divergence, or periodicity.

3.3.1. Parametric Space

We constructed a thorough three-dimensional parameter space for searching in order to methodically investigate the multidimensional nature of the nonlinear dynamical system that our model equations specify. This is accomplished by specifying discrete sets of intervals, created using locations that are equidistant by 8, in which the values of the system parameters vary:

,

, and

, individually within the range

. With different configurations

= 512, the resulting parametric grid then enables us to investigate a wide range of dynamical behaviors. The

grid was chosen as a convenient sampling option in order to sample a large parameter space in three dimensions and have the simulations manageable, since each parameter combination was also sampled in a variety of initial conditions and coupling strengths. Simulation behaviors are classified and characterized under a variety of initial conditions to achieve robustness. Dynamics that are not visible in a single-trajectory analysis can be revealed with the use of this multi-initial condition technique.

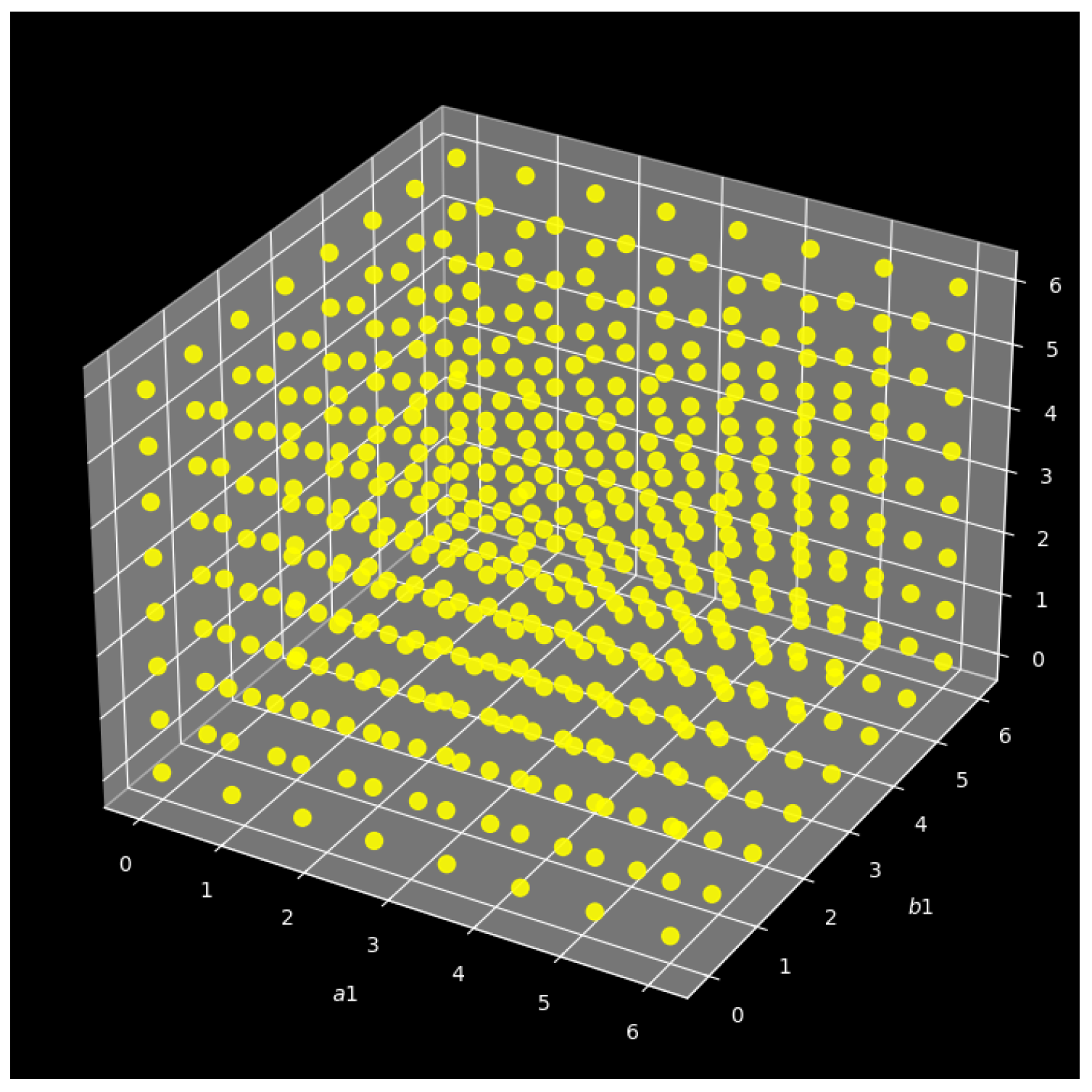

Figure 1 provides a graphic representation of the parametric space generated, with each point denoting a specific set of parameter values selected within the given limits. This hierarchical structure makes it possible to directly comprehend how modifications to the parameters impact the behavior of the system.

3.3.2. Categorization Based on Statistical Properties

In this analysis, we will explore the effect of the coupling strength (

) and the varying initial conditions on the long-term dynamics of a nonlinear dynamic system. We shall similarly vary (

) and run the system under initial conditions that differ substantially and seek to discern the impact of

on how the trajectories evolve within a three-dimensional parameter space spanned by

,

, and

. Every trajectory is classified according to the statistical behavior, which is periodic, divergent, or non-divergent. Constant displays this type of classification through

scatter plots in which every point within the parameter space is colored according to the behavior produced. The results are obtained for three coupling strength values (

, 0.1 and 0.2) and three representative initial conditions [

], [

], and [

]. This twofold variation enables us to measure the sensitivity of the system to either internal structure or external coupling and to measure how the dynamics are stabilized into periodic attractors by the growing coupling across a wide range of initial set-ups. The complete ODE-based behavioral classification, a processor of all trajectories, took an average of 8 min of computational time.

Figure 2 shows the classification of the behavior of the system according to the parameter statistics in the parameter space under varying initial conditions and coupling strengths.

Table 4 shows the category and description of system behavior.

Table 5 shows the summary of the behavior categorization across the initial conditions and the values

. A tabulated summary of the behavior of the system in terms of the initial conditions and the strength of the coupling among various combinations can be obtained in

Table 6.

Subfigures (a–c): Initial condition = [−0.20, −0.20, −0.20]

- (a)

When , a large number of red points can be seen (divergence), as well as green (periodic). This is a sign that the system, in which there is no coupling, is unstable in many places.

- (b)

, all points turn pink, indicating complete periodicity. This is a stabilizing influence brought about by the coupling.

- (c)

With , the preponderance is overtaken by yellows. The system is fully periodic, which means that a greater coupling results in uniform boundedness.

Subfigures (d–f): Initial condition = [−0.20, −0.20, 0.10]

- (d)

When , the parameter space is already mostly filled with periods (green), and the remaining divergent points are only small.

- (e)

When , the whole system is periodic (pink). The divergence is destroyed by coupling.

- (f)

At , fully periodic (yellow), but with even more extreme coupling, indicating a highly robust regime.

Subfigures (g–i): Initial condition = [−0.20, 0.10, −0.20]

- (g)

At , they have a heavy red presence: most of the space is diverging. The outcome of this inability to couple is a set of highly unstable trajectories.

- (h)

, fully periodic (pink) dramatic stabilization through coupling.

- (i)

With , the entire parameter space changes again to periodic (yellow) and confirms that consistency and robustness are rooted in coupling.

Notable Outcomes

Effect of Initial Conditions: The initial conditions have a great influence on the long-term behavior of the system in the absence of coupling. An example is the initial condition

, see

Figure 2g, which shows a high divergence in the case of no coupling.

Coupling Strength Effect (): By altering the coupling strength between the interacting systems, from to finally , the system moves through a mixed or divergent behavior into a complete periodic behavior. This indicates the fact that coupling creates a stabilizing factor of the dynamics.

3.3.3. Distribution Chart

In this section, we analyze in a systematic way how parameter setting and the coupling strength

affect the long-term behavior of the system, which can take one of three forms: diverging, periodic, and non-diverging. The rationale for this analysis is to gain additional insight into how sensitive the system is to the inter-node interactions and initial states, which are diagnostic issues in nonlinear and brain-inspired dynamics. For this purpose, we simulate the system in a three-dimensional parameter space

and produce 512 different parameter points for each combination of the coupling coefficient and initial condition. These results are plotted as a bar graph where three different values of the coupling coefficient are considered, namely

(no coupling),

(moderate coupling), and

(strong coupling). It is such a systematic comparison that will enable us to assess the effects of introducing and increasing the coupling on the stability and periodicity of the system within the entire parameter space. By studying how the behavior changes from divergence to periodicity as

assumes larger values, we obtain clear indications of how controllable and robust the system is. The findings may be relevant, especially where one wishes to have a stable or oscillatory system, e.g., in designing neuromorphic circuits or in adaptive control of large systems.

Figure 3 indicates the bar charts of the categorized behavior (diverging, periodic, non-diverging) of the system for the different values of

and different initial conditions.

Table 7 summarizes the key observations drawn from the behavioral analysis across different coupling strengths.

The figure indicates the distribution of the behavior under three initial conditions when no coupling is taken into account (). The initial condition provides the principal period behavior since it is manifested by the high yellow bump. In reverse, the initial conditions lead to a much higher amount of divergence behavior, as illustrated by the red bars. This implies that the system is quite sensitive to the initial state or slight variation, and without coupling, the system will jump between stable oscillations and unstable divergence. It can also be observed that there is practically no non-divergent behavior considered under this setting, which indicates that local feedback is not enough to stabilize the system.

A significant change in behavior is recorded with a moderate degree of coupling (). The three initial conditions yield 512 periodic behaviors that are all represented by uniformly tall bars of pink color. This result demonstrates that system responses move to limit cycle oscillations as inter-node coupling is introduced and that inter-node coupling prevents divergence (and fixed-point convergence). This kind of convergence of initial conditions implies that even a moderate coupling causes a decrease in the sensitivity of the system to changes in the initial state, such that robust, rhythmic dynamics occur over the entire parameter space.

With high coupling strength (), the system experiences another qualitative change—this time, fully periodic behavior in all initial conditions. This can be seen by the fact that the solid green bars show that in all 512 simulations, each initial condition converges to a limit cycle. As opposed to moderate coupling territory, where there was also dominance in periodicity, this behavior is even more stable and regular, with no indication of divergence or convergence toward a fixed point. What this means is that strong coupling does not just inhibit instability, but also, in fact, increases the robustness of the oscillatory process so that it is completely persistent, irrespective of initial conditions.

3.3.4. Coordinate Plots

The parallel coordinate plots showing the classification of system behavior for various values of the coupling factor

, under identical initial conditions

,

, and

are represented by

Figure 4. By mapping the normalized values of the parameters and coloring the trajectory according to the behavior, each graph illustrates how the parameters

,

, and

affect the behavior of the dynamical system, whether it is divergent, non-divergent, or periodic. These visualizations provide a concise representation of how the system will develop in relation to different internal parameters, focusing on the effect that initial conditions and coupling have on the dynamical characteristics of the system. The results of the classification of behavior into coordinate graphs are provided in

Table 8 and represent how the various combinations of initial values, values of the coupling parameters, and strengths result in behavior.

Subfigures (a–c): Initial condition = [−0.20, −0.20, −0.20]

- (a)

, IC: [−0.20, −0.20, −0.20]

There is a strong occurrence of blue (periodic) and some red, which implies that, in the absence of coupling, the system can access chaotic and unstable regions. The parametric space has sensitive dynamics due to the absence of interaction.

- (b)

, IC: [−0.20, −0.20, −0.20]

Yellow is overwhelming in the plot; this signifies that the system turns completely periodic with weak coupling. This demonstrates moderate stabilization that verifies that the existence of external node information is sufficient to overcome the effect of divergence.

- (c)

, IC: [−0.20, −0.20, −0.20]

Purple sweeps it away entirely, indicating very regular periodic behavior, which can even be symmetrical. This signifies a healthy stabilization, in the sense that the coupling is so tight that bounded, repeated behavior holds in larger parameter intervals as well.

Subfigures (d–f): Initial condition = [−0.20, −0.20, 0.10]

- (d)

, IC: [−0.20, −0.20, 0.10]

The predominance of blue indicates that the system is largely periodic, likely due to the chosen initial condition. This IC makes the system very periodic, even though it is not coupled.

- (e)

, IC: [−0.20, −0.20, 0.10]

The completely yellow region indicates a uniform periodic regime with particularly strong convergence across the parameter space. This periodicity is further enhanced by coupling.

- (f)

, IC: [−0.20, −0.20, 0.10]

The fully purple region indicates that under strong coupling, the dynamics move to a symmetric periodic regime, which may also include a decay or uniform cycle formation.

Subfigures (g–i): Initial condition = [−0.20, 0.10, −0.20]

- (g)

, IC: [−0.20, 0.10, −0.20]

There is a predominance of blue and red; this indicates a chaotic or divergent regime; thus, without coupling, such an initial condition results in unstable behavior throughout most of the parameter space.

- (h)

, IC: [−0.20, 0.10, −0.20]

The completely yellow region indicates that periodic dynamics are in control, implying that, in the case of unstable ICs, even weak coupling can induce order, eliminating divergence.

- (i)

, IC: [−0.20, 0.10, −0.20]

Again, completely purple, indicating that in the case of strong coupling, periodicity is strengthened, and all instability is eliminated. The complete boundedness and repeatability are confirmed.