1. Introduction

With the rapid development of artificial intelligence technology, digital humans (meta-humans) have been applied to news anchors, virtual e-commerce live streaming, AI-assisted teaching, and humanoid robots. Generating appropriate expressions for digital humans and robots will improve their visual impact. Therefore, the recognition, analysis, and generation of digital human facial expressions are topics worthy of study. The recognition and analysis of facial expressions provide the technical basis for facial expression generation.

Facial expression is one of the most intuitive external manifestations of human emotions and psychological states, playing a vital role in human communication throughout history. Facial expression recognition (FER) is an important research direction in computer vision and pattern recognition, aiming to equip computer systems with the ability to interpret the emotional information in human facial expressions. In the field of human–computer interaction, it can enable computer systems to perceive users’ emotions more naturally and intelligently, thereby optimizing the interactive experience. For example, intelligent customer service can adjust the response strategy according to users’ expressions and enhance quality of service [

1]. In medical health, it can assist doctors in diagnosing patients’ mental states and help with mental health assessment and disease monitoring [

2]. In security monitoring, it can provide timely warnings of potentially dangerous behaviors by identifying abnormal expressions, ensuring public safety. In recent years, the generation of digital humans and the widespread use of humanoid robots have also made facial expression recognition applicable in a large number of scenarios.

Since the 20th century, research on facial expression recognition has been widely conducted. Early on, due to limitations in computer performance and image processing technology, research on facial expression recognition focused on developing basic theory and exploring simple approaches. With the rapid development of computer technology, especially the iterative advancement of image processing, pattern recognition, machine learning (ML), and related technologies, FER research has gradually shifted from traditional methods based on prior knowledge to deep learning (DL) models. Traditional methods often use geometric features, such as the relative position and contour shape of facial organs, or texture features, such as local binary pattern (LBP) and its variants, to extract the features of expression, and then combine support vector machine (SVM) and adaptive boosting (AdaBoost) classifiers to realize expression classification [

3]. With the development of deep learning, convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and their derived models have been widely used. CNNs’ powerful image feature extraction capabilities allow them to automatically learn multi-level features from expression images [

4]; RNNs can effectively process expression sequence data and capture dynamic changes in expression over time [

5]. In addition, some hybrid learning (HL) methods integrating multiple features or models have emerged in the field of deep learning technology, such as cascaded networks and multimodal models [

6], aiming to fully leverage the advantages of different technologies and improve the performance of expression recognition technologies [

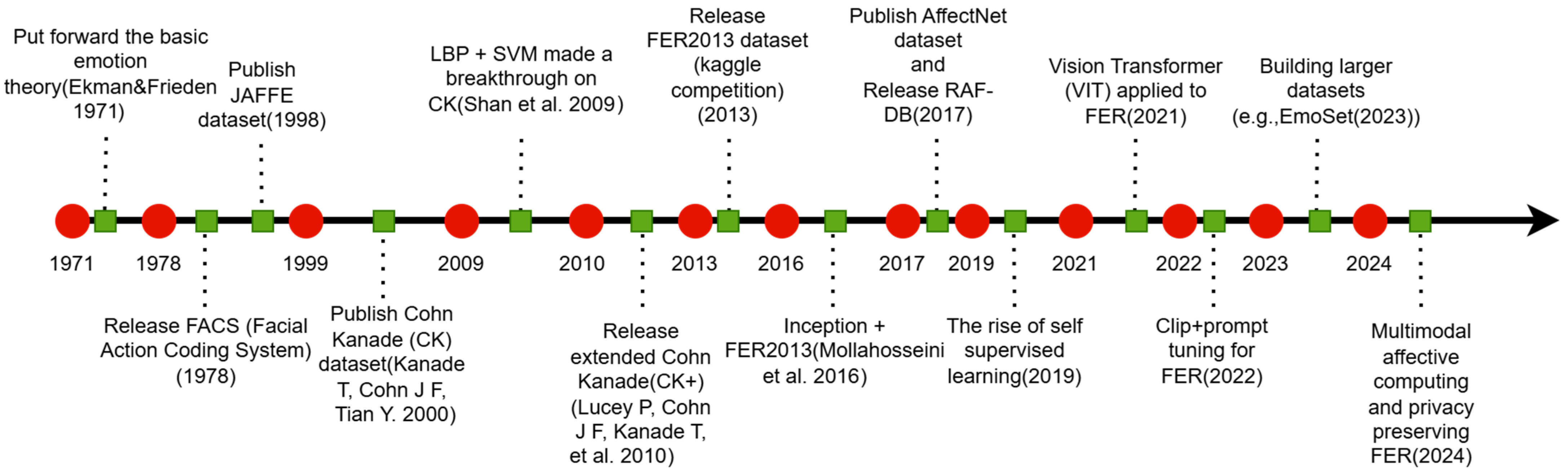

7]. The general history of facial expression recognition is shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows the development timeline of FER, which can be summarized into the following key stages:

- i.

Theory and data foundation (1971–2000): In 1971, Ekman and Friesen [

8] proposed the basic emotion theory applicable across cultures, before establishing the facial motion coding system (FACS) in 1978, defining action units (AUs), which laid the theoretical foundation for subsequent algorithm annotation. To support data-driven research, the Jaffe dataset was released in 1998, and the CK dataset was released in 2000 [

9], establishing an early standard for expression recognition in controlled environments.

- ii.

Machine learning and Feature Engineering (2009–2012): This period focused on the effectiveness of manual features. In 2009, Shan et al. [

10] demonstrated that combining local binary patterns (LBPs) with SVMs achieved a breakthrough performance on a Cohn–Kanade dataset. In 2010, the release of the extended CK dataset [

11] provided more complete annotations for action units and emotion, and these factors remain important benchmarks.

- iii.

Deep learning and field challenges (2013–2019): The release of FER2013 in 2013 marked a shift in research focus to large-scale “in the wild” data. Subsequently, Mollahosseini et al. [

12] successfully applied the concept and other deep networks to FER. In 2017, the release of AffectNet and RAF-DB further developed the field to address the complexity of real-world expressions (e.g., complex emotions). Self-supervised learning (such as SimCLR) also began to affect the FER pre-training paradigm in around 2019.

- iv.

Transformer and multimodal integration (2021-present): Since 2021, vision transformers (VITs) have been systematically introduced into FER to capture global dependencies. The EmoSet released in 2023 represents a trend toward larger-scale, richer visual emotion data. The current research frontier is gradually shifting toward multimodal fusion (images, voices, and physiological signals) and exploring privacy-preserving technologies.

Although FER technology has made significant progress, it still faces many significant challenges in achieving wider applications. One problem is the changeable real environment. Dramatic changes in lighting conditions, facial gestures from different angles, and partial occlusion caused by wearing masks and glasses will seriously compromise the accuracy of expression recognition [

13]. Another challenge is the richness and diversity of human expressions. In addition to basic expressions such as happiness, surprise and sadness, there are many subtle and fuzzy composite expressions, which are difficult to identify [

14] accurately; the differences in the facial structure and muscle movement patterns of different individuals, as well as the diversity of expression and understanding in individuals from different cultural backgrounds, all add difficulty to the construction of a unified and accurate expression recognition model [

15]. In addition, reducing the model’s parameter count and floating-point operations is a challenge. The lightweight model can be better deployed on some edge devices, reducing deployment costs [

16]. Therefore, in the absence of a unified standard method, in this study, we survey the existing methods to help researchers further promote the development of expression recognition technology, as well as to select appropriate methods according to different needs. Unlike most existing reviews [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21] that focus on text analysis, i.e., comparing data, conclusions, method names, ideas, and performance indicators, we add a comprehensive experimental comparison. The similarities and differences between our review and these existing reviews are listed in

Table 1. As shown in the table, the highlights of this study include a detailed literature review, algorithmic comparisons across multiple datasets, and suggestions for future research directions using large language models (LLMs).

The main contributions of this study include the following three points:

We review some typical facial expression recognition methods by category, based on the theoretical ideas and modeling tools of the algorithms. The selection criteria for a reference to be included in this review are twofold. The first is that it selects at least one representative method from each category or subcategory. The second is that it selects a reference that proposed a method that was significant or showed significant technological progress.

We compare the performances of 12 FER algorithms based on 4 outdoor facial expression datasets. Comparisons of experiments using the same dataset on the same computer are lacking in many existing review articles.

We propose potential future research directions in the field of FER, especially by combining LLMs and digital human technology, based on summarizing the gap between the existing methods and the future demand of technology.

The structure of this paper is as follows: The second section introduces the standard preprocessing technology used for facial expression data. In the third section, the existing expression recognition methods are reviewed, including traditional feature extraction methods and deep learning methods. In the fourth section, several typical FER methods are summarized, and comparative experiments are conducted to reveal the performances of these methods. Finally, the fifth section summarizes the conclusion and points out future research directions.

2. Preprocessing

In FER, data preprocessing can improve model performance. Due to the poor quality of public facial expression datasets, problems such as face occlusion, non-uniform lighting (too dark or too bright), and blurred or low-resolution images often occur, significantly affecting the accuracy of feature extraction and classification. Therefore, it is usually necessary to preprocess the original image to reduce noise interference and improve data consistency. Here, we present several image preprocessing methods used in facial expression recognition.

Face detection and alignment are used to locate the face and align the positions of facial features (such as the eyes and mouth corners) [

22]. Zhang et al. [

23] proposed a multiple-task cascaded convolutional network (MTCNN) for face detection and alignment. This method achieves robust detection across multiple poses and complex lighting conditions by refining candidate boxes iteratively and combining face detection and keypoint localization. Wang et al. [

24] introduced the image inpainting and the structural similarity index measure (SSIM) method to address the occlusion problem in expression images. They used completion technology based on structural constraints to fill the occluded area and ensured the overall consistency of the repaired image and the original face through structural similarity.

Normalization and scale adjustment are used to normalize the input image. After normalization, these input images are resized to a fixed size and normalized to a uniform gray range (e.g., [0,1] or a standard normal distribution), thereby avoiding training instability caused by resolution differences or inconsistent pixel value ranges. Cootes et al. [

25] used the active appearance model (AAM) to realize the geometric normalization of the face. By jointly optimizing the shape and texture models, this method aligns different face images to a unified reference coordinate system, enabling comparisons of changes in expression in a structured space.

Illumination and contrast enhancement can be implemented using histogram equalization, gamma correction, or adaptive brightness adjustment, thereby alleviating feature distortion caused by changes in illumination intensity. Pizer et al. [

26] used adaptive histogram equalization to improve image visual quality by enhancing local contrast. This method can maintain good texture details across different lighting conditions, thereby alleviating the interference of lighting differences on expression feature extraction.

Image enhancement and denoising can be achieved using smoothing and super-resolution reconstruction. Tomasi and Manduchi [

27] proposed a bilateral filtering method combining spatial-domain and pixel-intensity-domain weights to remove noise while preserving image edges. When applied to facial images, this method can effectively reduce blur and noise and improve the identifiability of facial texture features.

In general, reasonable preprocessing can not only effectively alleviate adverse factors such as occlusion, illumination, and blur but also enhance the discriminability of feature expression to a certain extent, thereby improving the facial expression recognition performance of subsequent traditional machine learning or deep learning models.

3. Facial Expression Recognition Method

This section reviews the FER methods developed and applied in the past 20 years. These methods can be divided into two categories according to whether it is necessary to actively extract features: methods based on prior features (machine learning-based methods) and methods based on deep learning (deep learning-based methods). The former type relies on researchers to design features (such as facial texture and organ position) and extract features based on prior knowledge to recognize facial expressions, such as SVM algorithm, which offers fast speed and strong interpretability when constructing classifiers. However, its effect depends on the characteristics of the data and the design, and its generalizability is generally weak. The latter type is based on deep learning and can automatically learn features, such as a convolutional neural network, offering high recognition performance but weak interpretability and a high parameter learning cost. The main progress in the development of the FER methods is outlined in the following subsections. Although the models selected overlap with the above survey references, our survey covers both classic manual features and the latest architectures from 2024 to 2025, providing an effective technical supplement to the existing survey literature.

3.1. Methods Based on Prior Features

The prior features listed here refer to the statistics constructed by researchers based on specific theories, mainly including wavelet transform (WT), local binary patterns (LBPs), histogram of oriented gradients (HOG), the gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM), local phase quantization (LPQ), and scale-invariant feature transform (SIFT). The methods are described in detail below.

Figure 2 shows the general traditional machine learning method flow for classification tasks.

3.1.1. Wavelet Transform-Based Method

Wavelet transform has a good effect in terms of extracting the texture features of facial expressions, so it is also used in expression recognition. For example, using Gabor wavelets, a key complex function of the method is

where

are the coordinates of pixel points;

is the wavelength of the sine wave, where the smaller the value, the finer the detection;

is the direction of the filter; and

is the phase offset. When

= 0, it represents the even symmetric filter, and when

, it represents the odd symmetric filter;

is the standard deviation of Gaussian function, which controls the size of the filter window, while

is the spatial aspect ratio.

We searched for articles from 2000 to 2024 on the “IEEE Xplore” platform using the keyword “facial expression recognition” and obtained 15,924 results. Then, we added the keyword “Gabor” to the advanced search function and obtained 1107 results. This shows that the Gabor filter plays a role in expression recognition due to its excellent texture analysis capabilities across multiple scales and orientations. In 2008, Bashyal et al. proposed a method of facial expression recognition using Gabor wavelet and learning vector quantization [

28]. The method noted that the two-dimensional Gabor function is a plane wave with wave factor

, which is limited by a Gaussian envelope function with a relative width

:

where

is set to

when the image has a resolution of 256 × 256. A set of discrete Gabor kernels is used, which are the spatial frequencies

and six different directions from 0° to 180° (every 30°). A filter group consisting of 18 filters is obtained. The filter group is applied to 34 target points of the image to obtain the feature vector. Then, principal component analysis (PCA) is used to reduce the dimension. Finally, classification is performed using learning vector quantization.

Zhou et al. [

29] proposed a quaternion wavelet transformer (QWTR) in 2025. This method is oriented toward facial expression recognition in a complex field environment. It aims to address the decline in recognition accuracy caused by factors such as illumination changes, head pose deviations, and occlusions. This method combines quaternion mathematical theory with transformer structure, and the overall framework is composed of three parts: quaternion histogram equalization (QHE) is used to enhance image brightness and contrast and maintain color structure; quaternion wavelet transform-based feature selection (QWT-FS) extracts high-quality emotional features by decomposing and filtering the most relevant wavelet coefficients; quaternion-valued transformer (QVT) integrates a quaternion CNN and a multi-head attention transformer module to jointly model facial emotional information from local and global levels. The experiment was carried out on four typical FER in-the-wild datasets (RAF-DB, AffectNet, SFEW, and ExpW). QWTR surpassed the current state-of-the-art model across many evaluation metrics, demonstrating excellent robustness and generalization. Particularly in challenging scenes such as illumination changes, skin color differences, occlusions, and negative postures, the model maintains stable, efficient recognition performance.

3.1.2. Local Binary Pattern-Based Method

Local binary pattern (LBP) is also used to extract texture features. The idea behind this method is to describe the local texture features of an image by comparing the gray values of each pixel with those of its adjacent pixels. Let the central pixel be

and its corresponding gray value be

. The gray value of the

adjacent pixels of the pixel is

:

It is referred to as the 0–1 encoding of the ith-nearest-neighbor pixel. Then, it arranges the 0–1 codes of the adjacent pixels in clockwise or counterclockwise order to obtain a binary code and convert it to decimal to obtain the LBP value of the central pixel. At present, many improved versions of the traditional LBP method have been developed, such as circular LBP and rotation-invariant LBP. In facial expression recognition, the face can be divided into multiple regions, LBP histograms are created on each region, and then histograms are concatenated to form feature vectors.

Benniu et al. [

30] combined LBP (local binary pattern) and ORB (Oriented FAST and Rotated BRIEF) features for facial expression recognition on the CK+, JAFFE, and MMI databases, demonstrating that this feature extraction method was effective. ORB comprises four steps: fast detection of key points, Harris corner response filtering, calculation of key point directions, and a brief description of the image around each key point. First, let

be a candidate corner,

be the intensity threshold set in advance, and

be

consecutive pixels around

.

is the gray value of point

. Similarly,

is the gray value of point

. If

for all

values, then point

is a corner. Given the possibility of overlapping corners, a non-maximum suppression strategy is adopted. Next, the main direction of the feature point, that is, the corner point, is calculated. Then, the region around the key points is described using the brief descriptor. Next, select several pairs of pixels around the feature points, compare their gray values, and express the results with 0–1. Finally, a binary code is formed.

3.1.3. Directional Gradient Histogram-Based Method

The histogram of oriented gradients (HOG) is often used to describe the local characteristics of an image by counting the distribution of gradient directions in a local region.

Firstly, the image is preprocessed to convert the color image into a gray image. Then, gamma correction is performed, that is, a power transformation is performed on each pixel value. Let

be the value of the pixel

. After gamma transformation, the new pixel value is

. Then, the Sobel operator is used to calculate the gradients

and

of the image in the horizontal and vertical directions. Then, the gradient amplitude

is obtained by

. According to

, calculate the gradient direction. The image can be divided into several patches, usually

or

pixels. In each patch, the gradient direction of each pixel is calculated and divided into nine intervals, either 0° to 180° or 0° to 360°. For each pixel, the gradient direction is used to determine the corresponding interval, and the gradient amplitude is added to it; finally, a nine-dimensional feature vector is formed. Pierluigi Carcagnì et al. [

31] verified the practicability of the HOG feature extraction method and discussed how to adjust HOG parameters to make it more suitable for the facial expression recognition task.

3.1.4. Gray-Level Co-Occurrence Matrix-Based Method

For any pixel (x, y) in an image and another point with a certain distance from it, let the gray value pairs of these points be . Assuming that the gray values are divided into intervals, there are intervals of such gray value pairs. Let traverse the entire image, count the number of occurrences of each gray value pair, and arrange it into a square matrix. The number of occurrences is normalized to the probability of the occurrence of each gray value pair. Such a square matrix is called a gray-level co-occurrence matrix. Let take a different combination, and then the gray-level co-occurrence relationships of pixel pairs at different distances and directions can be counted.

In 2014, Murty et al. [

32] proposed a facial expression recognition method based on the fusion of the gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) and distinctive local binary pattern (DLBP) based on a

first-order compressed image (FCI), which is used to accurately recognize seven kinds of expressions neutral, happy, sad, surprised, angry, disgusted, and fearful. The method consists of three steps: Firstly,

subimages are compressed into

subimages to retain key information. Secondly, two DLBPs (the sum of the upper-triangle LBP, SUTLBP, and the sum of the lower-triangle LBP, SLTLBP) are extracted from the triangular pattern of the upper and lower parts of the

subimage. Finally, GLCM is constructed based on DLBP, and characteristic parameters such as contrast, uniformity, energy and correlation are calculated for recognition. This method overcomes the generalization problem caused by the unpredictable distribution of facial images in real-world environments, a limitation of traditional statistical methods (such as PCA and LDA), and addresses the limitations of traditional LBP due to lighting, thereby improving classification performance by combining structural and statistical features. On the database containing 213 female facial expression images, the k-nearest neighbor classifier (k = 1) achieved an accuracy of 96.67%, significantly better than those of the two-tier perceptron architecture developed by Zhengyou Zhang [

33] and the expression analysis method developed by De la Torre F et al. [

34], and verified its effectiveness.

3.1.5. Local Phase Quantization-Based Method

By analyzing the phase information of the local region, detailed features of the image can be captured. Compared with the direct use of pixel values or other amplitude-based feature descriptors, phase information is more robust to illumination changes and image blur. This is because illumination changes mainly affect the image amplitude, rather than its phase. Local Phase Quantization (LPQ) is based on quantizing the phase information of the local Fourier transform. The specific calculation process is as follows: For a fixed-size window, the pixels within it are subjected to the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT). Let the image be

, the pixel be

, and its neighborhood be

. Then, the local Fourier transform of pixel

is

where

is the weighted window parameter, which is the commonly used Gaussian window, and

is the frequency vector. In most cases, four frequencies, recorded as

, are selected. Let

For each frequency point

, the symbols of the real and imaginary parts of the Fourier transform are calculated. Let

where

is the

j-th term of the vector

. Thus, an eight-bit binary number is obtained and converted into a decimal number. This decimal number is the LPQ value of pixel

. The image is then divided into several regions. The LPQ values for each region are calculated, and a histogram of the statistics is generated. Finally, the LPQ feature of the image is obtained by connecting the histograms of each region. At present, LPQ features have also been improved and varied.

Jiawaili et al. proposed a new facial expression recognition algorithm based on rotation-invariant local phase quantization (RI-LPQ) and sparse representation [

35]. RI-LPQ was used to extract expression features, combined with the sparse representation-based classification (SRC) method. The test image was represented as a linear combination of training images, and the expression was determined using sparse representation residual analysis. Compared with 2DPCA+SVM, LDA+SVM, and other algorithms, the new method achieves better performance and recognizes facial expression images with different occlusions.

Nikan et al. proposed a face recognition method combining multi-scale LPQ and multi-resolution LBP [

36]. First, the image is preprocessed to obtain a representation that is insensitive to illumination changes. Then, the image is divided into small sub-blocks, and LPQ and LBP features are extracted from them. By combining score-level and decision-level features, recognition performance under severe illumination changes is improved.

3.1.6. Method Based on SIFT

SIFT is a classic local feature extraction algorithm that was proposed by Lowe in 1999 [

37] and further improved in 2004 [

38]. Its core advantage lies in its robustness to image scaling, rotation, and illumination changes, as well as its good adaptability to angle changes and noise. In this method, the image is convolved with Gaussian kernels of different scales to generate a series of blurred images, and the differences between adjacent blurred images are calculated to obtain difference-of-Gaussian (DoG) images. In these DoG images, the local maxima or minima present within a 26-neighborhood area around each pixel at the current scale and adjacent scales are searched for candidate key points. Then, the gradient direction histogram in the neighborhood of the key points is calculated. These histograms are combined into a 128-dimensional feature vector and normalized. The SIFT feature is widely used in facial expression recognition. For example, Berretti et al. [

39] proposed an expression recognition method based on a 3D facial model, achieving a recognition rate of 78.43% on the BU-3DFE dataset by automatically detecting and combining key points and SIFT descriptors using an SVM classifier. In addition, Shi et al. [

40] proposed an improved SIFT algorithm to enhance the robustness of expression recognition under different lighting and pose conditions through shape decomposition and feature point constraint.

3.2. Deep Learning-Based Method

The deep learning-based method generally does not require researchers to design statistical features and directly uses the original image as input. Researchers mainly focus on the model architecture. The following are nine typical convolutional neural network models for facial expression recognition.

Figure 3 shows the general process of expression recognition using a deep learning method.

3.2.1. Facial Expression Recognition Based on Traditional CNN

In recent years, various classic CNN architectures (such as VGGNet, ResNet, and Inception) have been introduced into the field of expression recognition, leading to significant performance improvement. In 2023, Luo et al. [

41] proposed an improved CNN model by optimizing the convolution activation function and the classification layer loss function. Using the convolution activation function, the authors comprehensively consider the pixels of the facial expression image, the convolution operation times, and the pooling operation times and attain highly integrated feature extraction. Using the classification loss function, the weights and bias values of the convolution layer, pooling layer, and classification layer are defined, enhancing the flexibility of the model. In the experimental part, three gradient descent algorithms (e.g., Full Gradient Descent, FGD; Stochastic Gradient Descent, SGD; Mini-batch Gradient Descent, MGD) and six traditional models (LBP+SVM, CSLBP/RILPQ+SVM, DeeID, Deep Face, LeNet-5, and the improved CNN model) are proposed. The experimental results show that the improved algorithm achieves 87% classification and 88% recognition accuracy, outperforming other comparison methods. In 2024, Shehada et al. [

42] proposed two methods to improve facial expression recognition performance. The first method combines negative emotions (anger, fear, sadness, disgust) into a single category to simplify the classification task. The second method introduces diverse datasets. In terms of training and testing, the authors used 80% of the FER-2013, IMDB, AffectNet, and RAF-DB dataset samples for training; 20% of the FER-2013 samples for validation; and all CK+ samples for testing, achieving 90.9% and 94.7% accuracy on the FER-2013 and CK+ datasets, respectively.

However, challenges remain in distinguishing similar negative expressions, such as anger and disgust. In 2024, Adiga et al. [

43] proposed that, based on image preprocessing, a multi-layer CNN be used to automatically extract facial features, such as edges, textures, and shapes. During training, the probability of each emotion is computed using the softmax activation function, and the model is optimized with the Adam optimizer or the SGD optimizer using the cross-entropy loss function. The experimental results show that the model achieves high accuracy and generalization on the FER-2013 dataset, especially for happy, sad, surprised, and other emotions.

3.2.2. Residual Network-Based Method

Deep residual learning addresses the degradation problem during deep neural network training. This method uses the core strategy of residual mapping and shortcut connection. In expression recognition, ResNet is often used as a benchmark model for comparison with other methods. At the same time, ResNet is often used as a part of many neural networks to increase the depth of the network, enabling the model to achieve better results.

Istiqomah A A et al. [

44] used the pre-trained ResNet-50 network as the feature extractor in the expression recognition task and introduced transfer learning to improve the performance of the model; the Kaggle public facial expression dataset was used, with 80% used for training and 20% used for testing, and edge detection and region detection were used in preprocessing, with an accuracy of 99.49% and an F1 score of 99.60%. Jiahang Li [

45] systematically compared the performances of different depth variants of ResNet (ResNet-18, 50, 101, and 152) and the attention-enhancement variant SE-ResNet. They conducted experiments on the FER-2013 dataset and used image enhancement techniques (e.g., random cropping, horizontal flipping, and brightness and contrast adjustments) to improve the model’s generalization. The results showed that SE-ResNet-34 with medium depth achieved the best performance, with an accuracy of 70.80%, better than those of SE-ResNet-50 and SE-ResNet-101 with deep depth. Roy et al. [

46] proposed ResEmoteNet, which uses a CNN to extract hierarchical features, employs squeeze-and-excitation (SE) blocks to enhance key facial feature channels selectively, and combines residual blocks to alleviate the problem of deep network gradient disappearance and improve the learning of complex features. On the open-source datasets FER-2013, RAF-DB, AffectNet-7, and ExpW, the accuracy of ResEmoteNet [

46] was 79.79%, 94.76%, 72.39%, and 75.67%, respectively, surpassing the accuracies of APViT, S2D, and other methods.

3.2.3. Attention Mechanism-Based Method

In facial expression recognition, an attention mechanism can help the model to focus on highly correlated facial regions, such as eyes, mouth corners, and eyebrows, especially under complex conditions such as subtle expressions, facial occlusion, or lighting changes, thereby improving robustness. This mechanism can be implemented using two methods: the first method is embedding traditional convolutional neural network modules (such as SE and CBAM) to enhance feature expression; the second method uses a full-attention architecture (such as a transformer) to completely replace convolutional operations. Using the former method, channel attention mainly focuses on “which feature channels are more important”, while the latter method focuses on “which positions in the image are more critical”. This mechanism improves the model’s discrimination ability and effectively alleviates feature redundancy.

Considering the illumination change, occlusion, micro-expression, and other factors present during facial expression recognition, Shiwei et al. [

47] proposed a fine-grained method of global and local feature fusion, which achieved good classification performance through multi-stage preprocessing, such as super-resolution processing, illumination and shadow processing, and texture enhancement, before using a double-branch convolutional neural network to fuse global and local features.

Because the fuzzy annotation in the dataset will affect the performance of the model, Shu Liu et al. [

48] proposed solving FER tasks through the label distribution learning paradigm and developed a two-branch adaptive distribution fusion (ADA-DF) framework, which uses the attention module to give high weights to the determined samples and low weights to the uncertain samples. The model achieved high accuracy on RAF-DB, AffectNet, and SFEW.

Amine Bohi et al. [

49] proposed using ConvNeXt as the basic framework to enhance the robustness of the model with respect to scale, rotation, and translation changes and integrated an SE module to model the dependency between channels, highlight key features, and add self-attention regularization to enhance the balance and discrimination of feature expressions by balancing the attention weight. Ablation experiments showed that each module of EmoNext [

50] (STN, SE, and SA regular terms) achieves significant performance improvement.

In 2025, Cao et al. [

51] proposed a fuzzy perception recognition framework, COA, to address the issue of “wrong labels” and “fuzzy labels” in the sample. The COA framework introduces the emotion extraction and expression description modules. The former extracts rich semantic features from multi-scale and local attention mechanisms, respectively, via the coupled flow structure; the latter generates tag pairs by accurately predicting the probability, accurately describes the multiple emotional attributes of fuzzy samples, and better guides the model to fit mixed features during training. In the study, experiments were conducted on five datasets: RAF-DB, FERPlus, AffectNet, SFEW, and CAER-S. The results show that COA has significant advantages and robustness in dealing with a high proportion of fuzzy samples.

In 2024, Ngwe et al. [

52] addressed the challenge of FER under natural and complex conditions. They proposed the lightweight network Patt-Lite, which integrates a patch extraction block and an attention classifier based on the MobileNetV1 architecture to improve recognition performance. Experiments on CK+, RAF-DB, FER-2013, FERPlus, and other datasets showed that Patt-Lite achieves 100% accuracy on CK+ and 95.05%, 92.50%, and 95.55% accuracy on RAF-DB, FER-2013, and FERPlus, respectively; these outcomes are significantly better than those of existing lightweight methods and some transformer models. The parameter is only 1.10 M, demonstrating the method’s robustness under complex conditions.

3.2.4. Transformer-Based Method

The original transformer model is a deep learning architecture based on a self-attention mechanism proposed by Vaswani et al. [

53] in 2017. Unlike the traditional RNNs or CNNs, the transformer completely discards the cyclic structure and convolutional operations and relies solely on the self-attention mechanism to model dependencies between elements at different positions in the input sequence. It can simultaneously focus on global and local information in the sequence, significantly improving the model’s ability to understand context semantics. For facial expression recognition, the transformer-based model can effectively capture the subtle changes in key areas of the face (such as eyes, mouth, and eyebrows) and their correlation, focus on the discriminant features related to expression through the multi-level attention mechanism, and alleviate the influence of interference factors such as light and posture change.

In recent years, researchers have further improved the accuracy and robustness of the model in expression recognition by improving the input representation of the transformer (such as introducing facial key point information) and optimizing the attention mechanism (such as combining local attention and global attention), making it an important research direction in this field. In 2024, Raman et al. [

54] proposed a multimodal facial expression recognition (MMFER) framework based on a hierarchical cross-attention graph convolutional network (HCA-GCN), which improves recognition accuracy and robustness by fusing multimodal data such as visual images, audio signals, and contextual information. Firstly, a CNN, a Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) and a pre-trained transformer are used to extract modal features. Then, a cross-modal graph structure is constructed by layering graph convolutions. First, the internal features of the single mode are refined, and then the dynamic correlation between modes is captured. Finally, the dynamic weighted features of the layers are fused via cross-attention, and the resulting features are classified using softmax.

In 2025, Zhou et al. [

55] proposed a high-performance facial expression recognition model, HPC, including a high-dynamic-range preprocessing module (HDR preprocessing module), a parallel attention vision transformer structure (parallel attention vision transformer), and a co-expression head. During the preprocessing stage, the HDR preprocessing module optimizes the input image through local contrast and detail enhancement technology to enhance the adaptability of the model to light and detail changes. During the feature processing stage, the parallel attention visual transformer structure uses the multi-head self-attention mechanism encoder to capture and process the multi-scale facial expression features effectively and realizes the detailed analysis of subtle expression differences. In the feature fusion stage, the cooperative expression head uses the cooperative expression mechanism to efficiently process and optimize the features of different expression states.

In 2024, Liu et al. [

56] proposed a framework based on human expression-sensitive cues (HESPs) to capture subtle expression dynamics by improving the clip model, addressing the challenge of clip models being too complex to recognize unknown expression categories in open-set video facial expression recognition (OV-FER). The framework includes three modules: the text prompt module introduces the learnable emotion template and negative text prompt to optimize the expression ability of the text encoder for known/unknown emotions; the visual cue module uses the class activation map to locate the expression sensitive area, combining with the time global pool to aggregate the video sequence characteristics; and the open-set multi-task learning scheme enhances the ability of cross-modal feature alignment and unknown category generalization through known category loss, negative representation loss, and global prediction loss.

In 2025, Mao et al. [

57] proposed a lightweight, improved version of Poster++ to address the high computational cost of the Poster [

58] model in FER, achieving improved efficiency and performance by optimizing the dual-flow design, cross-fusion mechanism, and multi-scale feature extraction. The model removes the image from the original dual-flow structure and routes it only to the landmark branch, while retaining the landmark-to-image branch to focus on key expression features. At the same time, the window-based Multi-Head Cross Self-Attention (W-MCSA) mechanism replaces traditional cross attention, reducing computational complexity from quadratic to linear and enabling feature fusion by directly extracting multi-scale features from the backbone network and combining them with the two-layer transformer module.

3.2.5. Graph Structure-Based Method

In recent years, GNNs have directly modeled non-European spatial data, making them particularly suitable for processing graph-structured data composed of facial key points, providing a new idea for expression recognition. The graph-based expression recognition process comprises three steps:

- (1)

Construct the face image structure: Hundreds of facial key points are extracted using face key point detection methods (such as Dlib, MediaPipe, or OpenFace), and each key point is used as a graph node. Then, the adjacency matrix is generated using k-nearest neighbors (KNNs), full connectivity, or prior knowledge of facial anatomical structure, so that the relationship between nodes reflects local facial geometry.

- (2)

Graph neural network modeling: After obtaining the graph structure, the graph convolutional network (GCN) or its improved version is used to extract the features of the graph data. Node features (such as keypoint coordinates, texture features, or motion features) are updated via the graph convolutional layer to transmit and aggregate information between nodes. This enables the model to capture interactions among local facial regions, thereby enhancing its ability to model complex expressions.

- (3)

Classification and identification: After several layers of graph convolution, node features are usually transformed into a graph-level representation through global pooling. Finally, the fully connected layer and softmax classifier are used to output specific expression categories.

Many studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of the graph-based expression recognition method. For example, the FERGCN model proposed by Liao et al. [

59] uses the face’s key points as nodes, constructs an adjacency matrix to capture the face’s geometric relationships, and performs feature propagation via a graph convolutional network. This method can capture the dependence between local areas of the face, especially in highly sensitive regions such as the eyebrows, eyes, nose, and mouth corners. Liu et al. [

60] proposed a video expression recognition method based on graph convolution. Firstly, CNNs are used to extract local features from different regions of the face (e.g., eyes, mouth, and eyebrows), which are modeled as graph nodes. The edges between nodes connect region features, and GCN learns the interactions between regions.

Furthermore, to capture the temporal dynamics of expression, this method combines an LSTM to model temporal features and enables joint learning of space and time. Antoniadis et al. [

61] proposed an emotion GCN model to address the significant co-occurrence and semantic dependence among expressions. This method constructs a graph in the label space, treats different emotion categories as nodes, and establishes edges based on statistical co-occurrence or semantic relationships, enabling GCN to explicitly model dependencies between categories. In addition, the method combines two expression modeling methods—classification and regression—and further improves the model’s generalization ability through multi-task learning.

3.2.6. RNN-Based Approach

An RNN is a type of deep learning model designed for processing sequential data. Its core feature is that, by introducing cyclic connections, the model can retain historical input information and apply it to the current time calculation, thereby naturally capturing temporal dependence in the sequence. RNNs are often used to process video sequences, dynamic images, and other information that contain a time dimension. For facial expression recognition, especially dynamic expression recognition, RNNs can effectively model the evolution of expression over time, capture the transition characteristics from neutral expression to target expression, and determine the temporal correlation of the movement of various regions of the face (such as the speed of rising corners of the mouth, the amplitude of frowning, etc.). For example, by inputting the video frame sequence into an RNN, the model can learn the dynamic patterns of different expressions on the time axis and then improve the recognition ability of complex expressions (such as micro expressions) or fuzzy expressions.

Furthermore, traditional RNNs suffer from gradient disappearance or gradient explosion, making it challenging to handle long-term sequence dependence. By introducing input, forgetting, and output gates to control the inflow and outflow of information, LSTM can effectively alleviate the gradient problem and better capture the characteristics of long-term time series. Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) simplifies LSTM gating and reduces computational complexity while maintaining performance. These improved models have been widely used in facial expression recognition, especially when combined with dynamic information such as facial keypoint sequences and optical flow, thereby significantly improving the model’s sensitivity to temporal changes and recognition stability. Güler et al. [

62] proposed a multimodal emotion recognition framework integrating electroencephalogram (EEG) signals and facial expressions to address the limitations of single-modality approaches. They used deep learning models such as GRUs, LSTMs, and transformers to explore the synergistic effect of multi-source data on emotion classification. This method also needs to solve the problem of modal dimension mismatch. In 2025, Yuanlun Xie et al. [

63] proposed an end-to-end low-illumination FER framework (LL-FER), which realizes the collaborative optimization of image enhancement and expression recognition by jointly training the low-illumination enhancement network (LLENet) and the FER network.

4. Experimental Comparison

Although existing reviews cover a wide range of methods, most rely on data from original studies for comparison, lacking a unified experimental environment. The core contribution of this study is the establishment of a unified benchmark framework that rigorously compares 12 methods across different technical paradigms within the same hardware environment, data partitioning, and hyperparameter settings.

The selection of the 12 assessed models is based on three criteria. The first criterion is the historical baseline. We have chosen traditional manual feature extraction methods such as LBP, GLCM, and HOG. Although they are no longer SOTA, as classic representatives of the ‘pre-deep learning era’, they provide important baselines for benchmark testing, are representative, and reflect the evolutionary representativeness of FER technology. Based on this criterion, four traditional machine learning methods, namely GLCM-SVM [

32], HOG-SVM [

64], LBP-SVM [

30], and LPQ-SRC [

35], are selected.

The second criterion is paradigm coverage. The chosen method should cover the mainstream architectures of the deep learning era to ensure the breadth of method evaluation. According to this criterion, eight DL-based models, namely ADA-DF [

48], CNN-SIFT [

65], EmoNext [

50], FERGCN [

59], GCN [

66], ResEmoteNet [

46], ResNet [

67], and Poster (Pyramid Cross-Fusion Transformer) [

58], are selected. Among them, ResNet represents the classic convolutional neural network architecture. Poster and EmoNext are the most advanced attention-based methods currently available. FERGCN is a structured modeling approach for non-Euclidean data. ADA-DF is a specialized method for solving the problems of “class imbalance” and “label ambiguity”.

The third criterion is reproducibility. To ensure the fairness of this benchmark, we have selected models that provide official open-source code, thereby ensuring the reliability of the experimental results. This enables us to reproduce experiments with new datasets, rather than relying solely on the metric values reported in the original references.

According to the three criteria, 12 models are selected, and their publication years, method characteristics, and environmental configurations are listed in

Table 2.

4.1. Experimental Data

The comparative experiment was conducted using four datasets: AffectNet [

68], FERPlus [

69], FER-2013 [

70], and RAF-DB [

71]. The first two datasets both contain images of eight different facial expressions; the last two datasets both contain images with seven different facial expressions.

4.1.1. AffectNet

AffectNet (2017) [

68] is one of the largest and most challenging facial expression recognition datasets currently in use, and it is used to support research on expression recognition, emotion analysis, and multidimensional emotion modeling. It was built by the research team of Ohio State University, who collected more than 1 million facial images from the Internet. These images were automatically crawled using a search engine with emotional keywords and manually labeled. AffectNet provides two annotation methods: The first method uses seven (or eight) categories of basic emotional labels, including neutral, happy, sad, angry, surprised, disgusted, fear and contempt. The second method annotates the continuous emotion dimension, that is, each image has the corresponding value of happiness and arousal, which can be used for regression tasks and emotion distribution modeling. About 450,000 images in the dataset have human-labeled labels, and more than 500,000 have automatically generated labels. AffectNet reflects the complexity of the “real world” in terms of emotional category imbalance, posture change, expression subtlety, etc. It is one of the most important benchmark datasets for evaluating deep learning expression recognition models.

4.1.2. FERPlus

FERPlus (face expression recognition plus 2016) [

69] is an enhanced version of Microsoft Research relabeling based on the FER-2013 “wild” expression dataset produced in 2016: it retains the original 35,887 48 × 48 gray face images and the original training/public/private triad structure, but introduces the voting results of 10 crowdsourcing taggers for each image, as well as gives the count distributions for eight emotions (neutral, happy, surprised, sad, angry, disgusted, fear, contempt) and two auxiliary tags (“unknown” and “non face”); this ensures that either a single tag can be obtained with a majority vote or multi-tag or soft tag learning can be directly carried out using the probability distribution. Despite challenging low-resolution, real-world conditions, FERPlus has become a standard benchmark for studying noise-robust learning, expression distribution modeling, and depth network robustness.

4.1.3. FER-2013

FER-2013 (Facial Expression Recognition 2013) [

70] is a widely used facial expression recognition dataset, which Kaggle initially released in the 2013 “challenges in representation learning” competition. The dataset contains 35,887 grayscale face images, each with 48 × 48 pixels. Its data were collected from Google image searches and cover seven basic emotions: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, surprise, and neutrality. The images are all face regions subjected to automatic detection and alignment. Although there is a certain degree of noise and annotation error, its large scale, standard division (28,709 training sets, 3589 verification sets, 3589 test sets), and wide use make it one of the most classic benchmark datasets in the field of expression recognition. FER-2013 is often used for training and evaluating deep learning models, such as CNNs, ResNets, and VGGs. It plays an important role in robustness research for expression recognition, emotion classification, multi-task learning, and related areas.

4.1.4. RAF-DB

RAF-DB (Real World Effective Faces Database 2017) [

71] was proposed by Shan and Deng in the IEEE Transactions on Image Processing in 2017. It contains about 30,000 “in the wild” face images. Through crowdsourcing, each image is labeled by about 40 taggers on average, thus ensuring high reliability. The dataset includes 7 basic expressions (such as happy, sad, angry, etc.) and 12 complex expressions, and it provides face-keypoint information. It is widely used for facial expression recognition, complex emotion modeling, and robust learning and is an important benchmark dataset in the field.

Our experimental datasets were downloaded from Kaggle.

Table 3 provides a summary of the original dataset, and

Table 4 provides a summary of the number of various expressions in the datasets used in our experiment.

4.2. Implementation Details

In our experiments, we conducted analyses across two distinct computational setups tailored to model complexity. For traditional machine learning methods (GLCM-SVM, HOG-SVM, LBP-SVM, LPQ-SRC), we utilized a local workstation powered by an Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-14900HX CPU @ 2.20 GHz with 16 GB RAM. Due to the complexity of deep learning models and the large amounts of training data, they were trained on remote high-performance servers equipped with dedicated accelerators. Specifically, ADA-DF, EmoNext, ResEmoteNet, ResNet, and Poster were trained on a single NVIDIA RTX 4060 GPU (CUDA 12.4, PyTorch 2.5.1), while CNN-SIFT, FERGCN, and GCN were executed on a single NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPU (CUDA 12.8/9.0.176, PyTorch 2.8.0/1.1.0). The software environment spanned Python versions 3.7 to 3.11, ensuring compatibility with the original implementations.

The experimental settings of the four traditional methods are as follows:

GLCM-SVM: For the GLCM-SVM method, we implemented a hybrid feature extraction pipeline designed to capture texture statistics from quantized patterns. Input images were first transformed into Uniform LBP maps () and subsequently quantized into 15 discrete levels (DLBP). On these quantized maps, GLCMs were computed using three distances () and four orientations (°, 45°, 90°, 135°). Six statistical descriptors—Contrast, Dissimilarity, Homogeneity, ASM, Energy, and Correlation—were extracted and aggregated via their mean and standard deviation to form the final feature vector. The classification was performed using a linear SVM with a regularization parameter and a maximum of 5000 iterations, utilizing a random 80/20 train–test split strategy.

HOG-SVM: The HOG-SVM approach utilized the histogram of oriented gradients descriptor implemented via OpenCV to capture local shape and edge information. Input images were resized to pixels. We configured the HOG descriptor with a cell size of pixels, a block size of pixels, and a block stride of pixels. Gradient orientations were discretized into nine bins. Given the high dimensionality of the resulting feature vector, we employed an SVM with a Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel. The regularization parameter was set to 10, and the kernel coefficient was set to ‘scale’. Similarly to the GLCM method, the dataset was split randomly, with 80% for training and 20% for validation.

LBP-SVM: For the LBP-SVM method, we adopted a feature fusion strategy to combine global texture patterns with local keypoint descriptors. Texture features were extracted using uniform LBP () and represented as a normalized histogram. Simultaneously, ORB descriptors were computed with a maximum limit of 200 keypoints, which were then aggregated using mean pooling. These two feature sets were concatenated to form the final representation. Classification was conducted using a linear SVM (). Unlike the randomized splits used in other baseline methods, this experiment strictly followed the pre-defined training–validation splits provided by the respective datasets, with 80% for training and 20% for validation.

LPQ-SRC: The LPQ-SRC method employed local phase quantization features, which are known for their robustness to blur and illumination variations. The LPQ descriptor was configured with a local window size of , a frequency estimation parameter , and a correlation coefficient . The resulting feature codes were accumulated into a 256-dimensional histogram and normalized using a standard scaler. For classification, we utilized a sparse representation-based classifier (SRC). The overcomplete dictionary was constructed using all available training samples. The sparse coding problem was solved using the Orthogonal Matching Pursuit (OMP) algorithm with a sparsity constraint of non-zero coefficients, and the final class label was determined based on the minimum reconstruction residual.

The training superparameters of the deep learning models are listed in

Table 5. We optimized the solver configuration for different architectures: most models (ADA-DF, FERGCN, ResNet) use the Adam optimizer, while GCN and ResEmoteNet use SGD. Poster uses a more advanced SAM (sharpness-aware minimization) optimizer to improve its generalization ability. The learning rate falls within

according to the convergence characteristics of the model. All models were trained for 100 or 200 epochs, and the batch size was set to 16, 32, or 64 to accommodate the video memory limit.

4.3. Analysis of Experimental Results

The following two sections compare the 12 FER methods listed in

Table 2 in terms of performance and classification effect. The comparative experiment is based on the four datasets of AffectNet, FERPlus, FER-2013, and RAF-DB introduced in

Section 4.1.

4.3.1. Performance Comparison of Various Models

The experimental results of four traditional methods and eight deep learning methods across four natural datasets are listed in

Table 6. In this table, we can see that the depth model (ADA-DF [

48], EmoNext [

50], GCN [

66], ResNet [

67], ResEmoteNet [

46], and Poster [

58]) can generally achieve high accuracy on the training set. Some methods such as AffectNet and RAF-DB can even exceed 95% while also maintaining strong performance on the validation set, especially on the “in the wild” datasets, and the validation accuracy of the depth model is significantly higher than those of the traditional methods, showing good generalization ability and robustness to complex environments (such as different lighting, posture, and occlusion). In contrast, the traditional prior feature methods (CNN-SIFT [

65], GLCM-SVM [

32], HOG-SVM [

64], LBP-SVM [

30] and LPQ-SRC [

35]) perform pretty well on the training set. However, the accuracy on the validation set is generally low, especially on large-scale, real-world images, which are difficult to adapt to expression diversity and label noise, leading to significant performance degradation. In addition, it is worth noting that a deep learning model must not follow the assumption of the more complex, the better. Although ResEmoteNet [

46] has a large parameter count, its performance across multiple datasets is not the best, and it exhibits some overfitting. Moreover, although the traditional HOG-SVM [

64] method performs nearly perfectly on the training set, its performance on the verification set is clearly insufficient, indicating its limited generalization ability.

In contrast, the ADA-DF [

48] model achieves better recognition performance while maintaining low complexity through its double-branch structure, thereby verifying the effectiveness of constructing the loss function based on the actual label distribution. Particularly on the RAF-DB dataset, the model’s recognition accuracy is 89.44%, demonstrating strong generalization. However, there is still room for improvement in its performance on other datasets. The GCN [

66] model achieves good results across all expression recognition categories. Moreover, its performance is stable. The effectiveness of the Gabor feature in expression recognition is verified.

In expression recognition, in addition to accuracy, the number of parameters (trainable params) and computational complexity (MACS) of deep learning models are important indicators for evaluating their lightweight degree. Despite the high computational efficiency and low cost of traditional machine learning methods, the classification effect is poor; this study focuses on comparing the structural complexity of eight deep learning models: ADA-DF [

48], CNN-SIFT [

65], EmoNext [

50], FERGCN [

59], GCN [

66], ResEmoteNet [

46], Poster [

58] and standard ResNet [

67].

Table 7 shows significant differences in the number of parameters and calculations across different facial expression recognition models. High-performance deep networks such as ADA-DF [

48], EmoNext [

50], Poster [

58], and ResEmoteNet [

46] have tens of millions of parameters and G-level MACs. These models have strong expression capabilities and are suitable for training and reasoning on high-performance GPUs. The parameter count of the traditional convolutional network, ResNet [

67], is relatively small. However, due to the computational characteristics of the convolutional operation, its MAC count reaches 193.3 M, which still imposes a significant computational burden. The graph convolutional models GCN [

66] and FERGCN [

59] exhibit lightweight characteristics, especially FERGCN [

59], which has only 4.872 K parameters and 0.593 M MACs, making it very suitable for resource-constrained scenarios. CNN-SIFT [

65], as a method combining a priori features with a shallow network, is at a medium level in terms of the number of parameters and calculations, taking into account specific performance and efficiency.

We take eight kinds of expressions as examples. The input image size for EmoNext and Poster is 3 × 224 × 224 pixels. In contrast, the GCN model uses an input image size of 1 × 90 × 90 pixels. Other models have an input image size of 3 × 120 × 120 pixels. Additionally, the parameters and floating-point operations of each model are compared.

Overall, there is an apparent trade-off between the capacity and computational cost of facial expression recognition models. A deep network with a high number of parameters and high MACs can provide stronger learning ability, but the cost of training and deployment is high; lightweight models such as FERGCN [

59] occupy very low computing resources and are suitable for real-time or embedded applications, but their limited capacity may affect their performance in complex scenarios. Models representing a combination of the two, such as ResNet [

67] and CNN-SIFT [

65], strike a balance between performance and efficiency. Therefore, in practical applications, it is necessary to select appropriate models according to task complexity, computing resources, and real-time requirements.

4.3.2. Analysis of Identification of Each Category

We analyze the recognition accuracy of each model in each dataset. The recognition accuracy of a category is equal to the ratio of the number of correctly predicted pictures in the category to the total number of pictures in the category. The classification accuracies of each model on the validation sets of the four datasets are listed in

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10 and

Table 11.

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10 and

Table 11 show that the deep learning method is clearly superior to the traditional prior-feature method in facial expression recognition as a whole. The depth model, represented by ResNet [

67], ADA-DF [

48], EmoNext [

50], ResEmoteNet [

46], Poster [

58] and GCN [

66], can achieve high recognition accuracy in most expression categories, especially in common expression categories such as happy, neutral, and surprise, which shows that the depth model has significant advantages in feature extraction and complex pattern modeling. In particular, the ADA-DF [

48], Poster [

58], and GCN [

66] models achieve higher than 90% accuracy in some categories, reflecting their strong adaptability to high-quality annotations and grayscale images, as well as their ability to capture the fuzziness and diversity of expressions. From a global perspective, in “in the wild” datasets such as AffectNet and RAF-DB, the depth model can still maintain high performance. Recognition of some small sample categories, such as sadness, anger, and contempt, is slightly low. However, the overall accuracy is still significantly higher than those of traditional methods, reflecting the robustness of the depth method across complex scenes, varying lighting conditions, pose changes, and occlusions.

In contrast, traditional prior-feature methods (such as LBP-SVM [

30], HOG-SVM [

64], GLCM-SVM [

32], CNN-SIFT [

65], etc.) may achieve a certain level of accuracy on the training set. However, they are unstable on the verification set and have limited adaptability to rare expression categories and complex environments. The accuracy levels of some methods in a few categories are even below 20%, indicating that they struggle to capture the diversity and subtle changes in facial expressions fully.

Table 12 shows the average accuracies of both the ML-based and DL-based methods in recognizing different facial expressions. The average accuracy is calculated as a simple average of the data in

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10 and

Table 11. In

Table 12, we can see that the most difficult expression to recognize is contempt, with recognition accuracies of 10.00% and 40.06% for ML-based and DL-based methods, respectively. The accuracy of the ML-based method for identifying neutral is the highest at 35.25%; the DL-based method has the highest accuracy for identifying surprise, with 69.56%.

Overall, these results show that deep feature extraction and structured modeling methods can more comprehensively and effectively represent facial expression features, which is the mainstream and the most effective technical approach in current facial expression recognition research, and they also provide a solid foundation for further research on compound expression recognition, multimodal emotion understanding, and robustness improvement.

4.4. Discussion

Our experiment reveals a significant phenomenon: traditional machine learning methods (such as HOG-SVM and LBP-SVM) experience severe performance decline on natural scene datasets such as AffectNet and RAF-DB. The fundamental reason is the limitation of the feature extraction mechanism. Traditional descriptors are highly dependent on strict pixel alignment and local texture consistency. However, in the field, uncontrollable illumination, pose variations, and occlusion distort the distribution of these rigid features. In contrast, deep learning models (such as ResNet and Poster) extract high-level semantic features with spatial invariance via hierarchical convolutions or an attention mechanism, thereby adapting to complex environmental interference.

In addition, through in-depth analysis of accuracy differences across various categories (see

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10 and

Table 11), we observed that all methods performed better on RAF-DB in the “happy” and “neutral” categories than in the “sad” and “disgust” categories. This performance deviation directly reflects the dataset’s long-tail distribution (as shown in

Table 4). Due to the scarcity of minority samples, the model tends to overfit the majority during training to reduce the global loss, resulting in a fuzzy decision boundary for the minority. This shows that simply improving the model architecture cannot completely solve this problem, and future research must be combined with data resampling or cost-sensitive learning strategies.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

In this study, we surveyed facial expression recognition models from recent decades that employ both machine learning and deep learning methods. Machine learning-based methods were reviewed across six subcategories: wavelet transform, LBP, HOG, GLCM, LPQ, and SIFT. Deep learning-based methods were reviewed across six subcategories: CNNs, ResNets, attention mechanisms, transformers, graph structures, and RNNs. In this way, the technical details of various methods over the past few years can be seen at a glance, a feature that sets this survey apart from many existing surveys.

We examined four datasets and compared twelve models through a series of experiments. Our comparative experiments demonstrate the following: (1) The results indicate that deep learning-based methods outperform traditional machine learning methods on the validation sets. (2) Models with the highest number of parameters or floating-point operations (MACs) do not always perform the best. For example, although ResEmoteNet has the largest number of parameters (80.24 M), its accuracy on RAF-DB is lower than that of Poster with fewer parameters (71.8 M). This discovery emphasizes an important insight: efficient architecture design, such as effective feature fusion or attention mechanisms, is more critical than simply increasing network depth or parameter size. (3) Class imbalance remains the most significant bottleneck restricting the improvement of FER accuracy. All evaluated models, regardless of their architecture, exhibit significant performance degradation in categories with few samples. This indicates that the majority of classes largely dominate the current performance improvement.

Based on the literature review and the results of our comparative experiments, future research can be further developed in the following areas:

For dataset enhancement, in view of the widespread category imbalance in facial expression recognition tasks, we should strengthen the modeling and enhancement of a small number of emotion samples; at the same time, it is necessary to consider the complex factors in the real scene, such as blur, occlusion (e.g., faces with masks), illumination change, etc., to test the robustness of a model. In addition, facial expressions are related to ethnic and cultural habits. The observer’s cultural background will significantly adjust their perception and judgment of expression [

72], so it is necessary to establish culturally relevant facial expression datasets to improve the specificity of expression recognition. Cross-cultural datasets can also be established to examine the generalization of an FER method.

Regarding model accuracy, although existing models have achieved good performance in expression recognition, some fuzzy expressions (as shown in

Figure 4) are still not recognized accurately, indicating that they require further improvement.

Noting the outstanding performances of large language models in assisting scientific research over the past two years, exploring efficient feature-extraction and fusion mechanisms for FER with large language models is a promising direction for the coming years. In addition, because the emotional information conveyed by the face is limited, we can develop a multimodal emotion recognition model that combines it with other types of data containing emotional information to improve recognition accuracy.

In the training strategy, we can leverage multi-task learning, transfer learning, and label distribution-based modeling further to improve a model’s cross-dataset and cross-scene generalization performance and enhance its practicability and adaptability.

In terms of application prospects, with the rapid development of digital human technology and humanoid robots, facial expression recognition, as one of the key technologies for natural human–computer interaction, will offer broad application value across related fields. For example, in intelligent education, expression recognition can be used to monitor learners’ emotional states in real time. In medical and health care, it can provide new means for the auxiliary diagnosis of emotional disorders and pain intensity [

73,

74]. In intelligent customer service and human–computer interaction, it helps to improve the naturalness and affinity of the system. Finally, in safety monitoring and driving assistance, it can provide support for abnormal emotion or fatigue detection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and H.L.; validation, Y.L. and H.L.; formal analysis, Y.L. and Q.F.; investigation, Y.L. and H.L.; resources, Q.F.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L. and H.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.L., H.L. and Z.Z.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, Q.F. and H.L.; project administration, Q.F. and H.L.; funding acquisition, Q.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by State Key Laboratory of Aerodynamics, grant number SKLA-JSSX-2024-KFKT-05; and the Beijing Science and Technology Plan Project, grant number Z231100005923035.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AdaBoost | Adaptive Boosting |

| CBAM | Convolutional Block Attention Module |

| CLAHE | Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DLBP | Distinctive Local Binary Pattern |

| FER | Facial Expression Recognition |

| FGD | Full Gradient Descent |

| GLCM | Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix |

| GCN | Graph Convolution Network |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| HCA-GCN | Hierarchical Cross-Attention Graph Convolution Network |

| HDR | High Dynamic Range |

| HOG | Histogram of Oriented Gradients |

| LBP | Local Binary Pattern |

| LDA | Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| LPQ | Local Phase Quantization |

| MGD | Mini-batch Gradient Descent |

| MTCNN | Multi-Task Cascaded Convolutional Networks |

| ORB | Oriented Fast And Rotated Brief |

| OV-FER | Open-Set Video Facial Expression Recognition |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| QHE | Quaternion Histogram Equalization |

| QVT | Quaternion-valued Transformer |

| QWTR | Quaternion Wavelet Transformer |

| QWT-FS | Quaternion Wavelet Transform-based Feature Selection |

| RI-LPQ | Rotation Invariant Local Phase Quantization |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| SE | Squeeze-and-Excitation |

| SGD | Stochastic Gradient Descent |

| SIFT | Scale-Invariant Feature Transform |

| SLTLBP | Sum of Lower Triangle LBP |

| SSIM | Structural Similarity Index Measure |

| SUTLBP | Sum of Upper Triangle LBP |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| W-MCSA | Window-based Multi-Head Cross Self-Attention |

| WT | Wavelet Transform |

References

- Tombs, A.G.; Russell-Bennett, R.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Recognising Emotional Expressions of Complaining Customers: A Cross-Cultural Study. Eur. J. Mark. 2014, 48, 1354–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Lindenberg, H.; Moessnang, C.; Oakley, B.; Ahmad, J.; Mason, L.; Jones, E.J.H.; Hayward, H.L.; Cooke, J.; Crawley, D.; Holt, R.; et al. Facial Expression Recognition Is Linked to Clinical and Neurofunctional Differences in Autism. Mol. Autism 2022, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, X.; Lei, B. Facial Expression Recognition Based on Local Binary Patterns and Local Fisher Discriminant Analysis. WSEAS Trans. Signal Process. 2012, 8, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Deng, W. Deep Facial Expression Recognition: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2022, 13, 1195–1215. [Google Scholar]

- Hasani, B.; Mahoor, M.H. Spatio-Temporal Facial Expression Recognition Using Convolutional Neural Networks and Conditional Random Fields. In Proceedings of the 12th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2017), Washington, DC, USA, 30 May–3 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Khomidov, M.; Lee, J.-H. The Novel EfficientNet Architecture-Based System and Algorithm to Predict Complex Human Emotions. Algorithms 2024, 17, 285. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Ciftci, U.; Yin, L. Facial Expression Recognition by De-Expression Residue Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. Constants Across Cultures in the Face and Emotion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1971, 17, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanade, T.; Cohn, J.F.; Tian, Y. Comprehensive Database for Facial Expression Analysis. In Proceedings of the Fourth IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition, Grenoble, France, 28–30 March 2000; pp. 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, C.; Gong, S.; McOwan, P.W. Facial Expression Recognition Based on Local Binary Patterns: A Comprehensive Study. Image Vis. Comput. 2009, 27, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucey, P.; Cohn, J.F.; Kanade, T.; Saragih, J.; Ambadar, Z.; Matthews, I. The Extended Cohn-Kanade Dataset (CK+): A Complete Dataset for Action Unit and Emotion-Specified Expression. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–18 June 2010; pp. 94–101. [Google Scholar]