Bloom Filters at Fifty: From Probabilistic Foundations to Modern Engineering and Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations of Bloom Filters

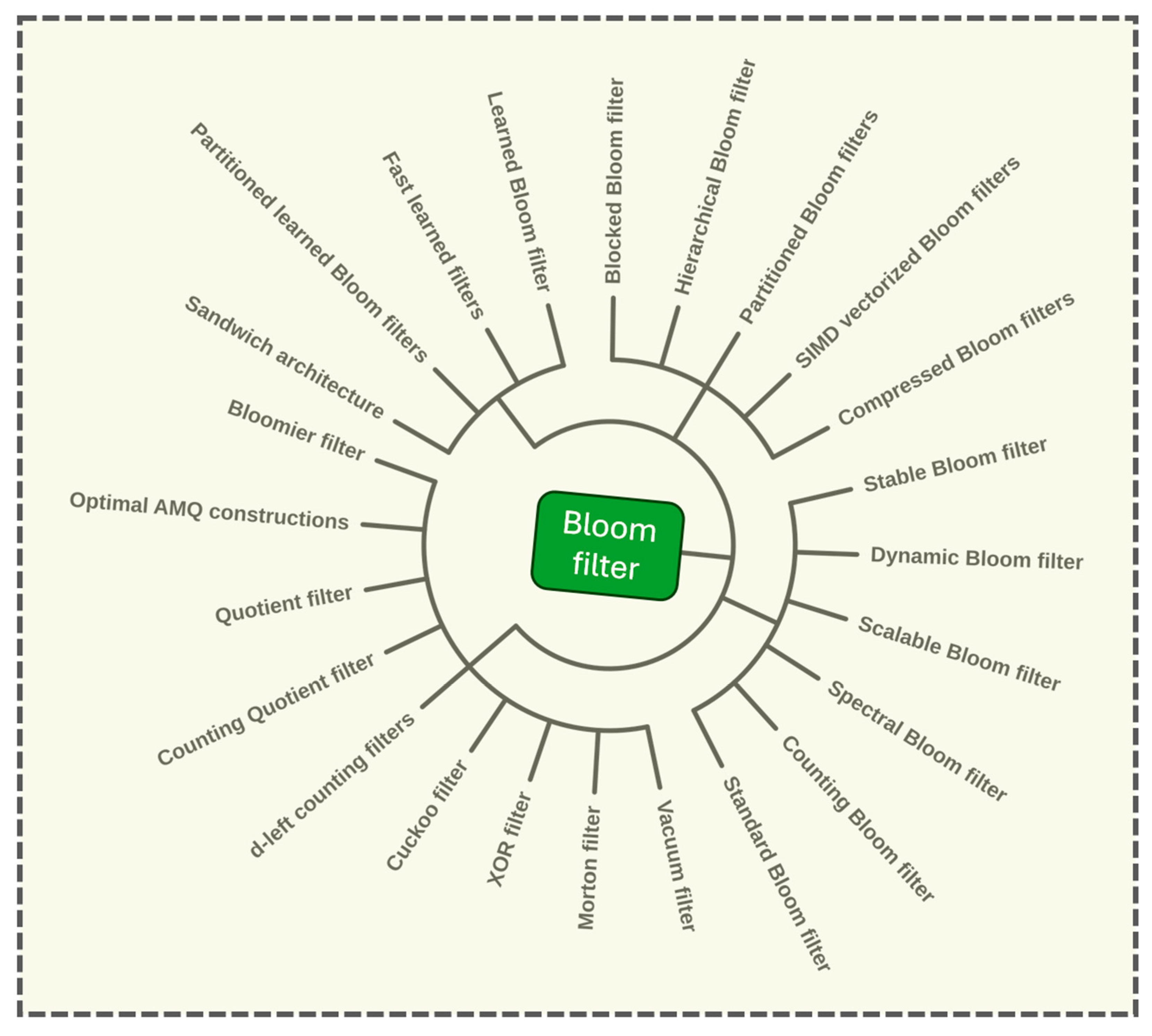

3. Engineering the Classic Bloom Filter

4. Functional Extensions and Variants

4.1. Counting Bloom Filters

4.2. Spectral Bloom Filters

4.3. Scalable and Dynamic Bloom Filters

4.4. Stable Bloom Filters

4.5. Partitioned and Hierarchical Bloom Filters

5. Beyond Membership: Bloomier Filters and Optimal Replacements

6. Modern Successors and Competing Data Structures

7. The Learned Bloom Filter Paradigm

8. Applications Across Domains

9. Security, Privacy, and Adversarial Robustness

10. Open Problems and Future Directions

10.1. Contemporary Context and Cross-Domain Relevance

10.2. Practical Interpretation of the Theoretical Framework

10.3. Security-Critical Risks and Future Directions

11. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BF | Bloom Filter |

| CBF | Counting Bloom Filter |

| DNS | Domain Name System |

| AMQ | Approximate Membership Query |

| SBF | Scalable Bloom Filter |

| StBF | Stable Bloom Filter |

| DBF | Dynamic Bloom Filter |

| QF | Quotient Filter |

| CQF | Counting Quotient Filter |

| XORF | XOR Filter |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| FPGA | Field-Programmable Gate Array |

| NIC | Network Interface Card |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Supplementary Implementation Example

Appendix A.2. Supplementary Glossary

References

- Bloom, B.H. Space/Time Trade-offs in Hash Coding with Allowable Errors. Commun. ACM 1970, 13, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broder, A.; Mitzenmacher, M. Network Applications of Bloom Filters: A Survey. Internet Math. 2004, 1, 485–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitzenmacher, M. Compressed Bloom Filters. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2002, 10, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, P.S.; Baquero, C.; Preguiça, N.; Hutchison, D. Scalable Bloom Filters. Inf. Process. Lett. 2007, 101, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomi, F.; Mitzenmacher, M.; Panigrahy, R.; Singh, S.; Varghese, G. An Improved Construction for Counting Bloom Filters. In Proceedings of the European Symposium on Algorithms (ESA), Zurich, Switzerland, 11–13 September 2006; pp. 684–695. [Google Scholar]

- Mitzenmacher, M. A Model for Learned Bloom Filters and Related Structures. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.00884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagniuc, P.A. Antivirus Engines: From Methods to Innovations, Design, and Applications; Elsevier Syngress: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch, A.; Mitzenmacher, M. Less Hashing, Same Performance: Building a Better Bloom Filter. Random Struct. Algorithms 2008, 33, 187–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagh, A.; Pagh, R.; Rao, S.S. An Optimal Bloom Filter Replacement. In Proceedings of the ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms (SODA), Vancouver, British Columbia, 23 January 2005; pp. 823–829. [Google Scholar]

- Dietzfelbinger, M. Universal Hashing and k-Wise Independent Random Variables via Integer Arithmetic without Primes. In Proceedings of the Annual Symposium on Theoretical Aspects of Computer Science, Grenoble, France, 22–24 February 1996; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (STACS). Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; Volume 1046, pp. 569–580. [Google Scholar]

- Mitzenmacher, M.; Vadhan, S. Why Simple Hash Functions Work: Exploiting the Entropy in a Data Stream. In Proceedings of the ACM–SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms (SODA), San Fracisco, CA, USA, 20–22 January 2008; pp. 746–755. [Google Scholar]

- Thorup, M. High Speed Hashing for Integers and Strings. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1504.06804. [Google Scholar]

- Putze, F.; Sanders, P.; Singler, J. Cache-, Hash-, and Space-Efficient Bloom Filters. J. Exp. Algorithmics 2009, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Matias, Y. Spectral Bloom Filters. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD), San Diego, CA, USA, 10–12 June 2003; pp. 241–252. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, G. Dynamic Bloom Filters. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (CIT), Xiamen, China, 11–14 October 2009; pp. 121–125. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L.; Cao, P.; Almeida, J.; Broder, A.Z. Summary Cache: A Scalable Wide-Area Web Cache Sharing Protocol. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2000, 8, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Byun, H.; Kim, S.W. Partitioned Bloom Filters. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference Communications (ICC), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 10–15 June 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Donnet, B.; Baynat, B.; Friedman, T. Retouched Bloom Filters: Allowing Networked Applications to Trade Off False Positives Against False Negatives. In Proceedings of the ACM CoNEXT Conference, Lisboa, Portugal, 4–7 December 2006; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chazelle, B.; Kilian, J.; Rubinfeld, R.; Tal, A. The Bloomier Filter: An Efficient Data Structure for Static Support Lookup Tables. In Proceedings of the ACM–SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms (SODA), New Orleans, LA, USA, 11–14 January 2004; pp. 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, B.; Andersen, D.G.; Kaminsky, M.; Mitzenmacher, M. Cuckoo Filter: Practically Better Than Bloom. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Emerging Networking Experiments and Technologies (CoNEXT), Sydney, Australia, 2–5 December 2014; pp. 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, M.A.; Farach-Colton, M.; Johnson, R.; Kraner, R.; Kuszmaul, B.C.; Medjedovic, D.; Montes, P.; Shetty, P.; Spillane, R.P.; Zadok, E. Don’t Thrash: How to Cache Your Hash on Flash. In Proceedings of the USENIX Workshop on Hot Topics in Storage and File Systems (HotStorage), Boston, MA, USA, 13–14 June 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Graf, T.; Lemire, D. XOR Filters: Faster and Smaller Than Bloom and Cuckoo Filters. J. Exp. Algorithmics 2020, 25, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alex, D. Breslow and Nuwan S. Jayasena. Morton Filters: Faster, Space-Efficient Cuckoo Filters via Biasing, Compression, and Decoupled Logical Sparsity. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2018, 11, 1041–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zheng, J.; Wang, K. Vacuum Filters: More Space-Efficient and Faster Replacement for Bloom and Cuckoo Filters. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference Data Engineering (ICDE), Anaheim, CA, USA, 3–7 April 2023; pp. 1611–1623. [Google Scholar]

- Kraska, T.; Alizadeh, M.; Beutel, A.; Chi, E.H.; Dean, A.; Polyzotis, N. The Case for Learned Index Structures. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGMOD International Conference Management of Data (SIGMOD), Houston, TX, USA, 10–15 June 2018; pp. 489–504. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Onizuka, M. Partitioned and Fast Learned Bloom Filters. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGMOD International Conference Management of Data (SIGMOD), Seattle, WA, USA, 18–23 June 2023; pp. 1650–1663. [Google Scholar]

- Naor, M.; Yogev, E. Bloom Filters in Adversarial Environments. In Proceedings of the International Conference Theory of Cryptography (TCC), Warsaw, Poland, 23–25 March 2015; pp. 565–584. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkas, B.; Schneider, T.; Zohner, M. Faster Private Set Intersection Based on OT Extension. In Proceedings of the USENIX Security Symposium, San Diego, CA, USA, 20–22 August 2014; pp. 797–812. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, C.; Chen, L.; Wen, Z. When Private Set Intersection Meets Big Data: An Efficient and Scalable Protocol. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference Computer and Communications Security (CCS), Berlin, Germany, 4–8 November 2013; pp. 789–800. [Google Scholar]

- Faber, S.; Jarecki, S.; Krawczyk, H.; Nguyen, Q.; Rosulek, M.; Steiner, M. Privacy-Preserving Data Sharing and Bloom Filters. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference Computer and Communications Security (CCS), Denver, CO, USA, 12–16 October 2015; pp. 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Niedermeyer, F.; Steinmetzer, S.; Kroll, M.; Schnell, R. Cryptanalysis of Basic Bloom Filters Used for Priva-cy-Preserving Record Linkage. J. Priv. Confidentiality 2014, 6, 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Zawoad, S.; Hasan, R. Providing Proofs of Past Data Possession in Cloud Forensics. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 5th International Conference on Cloud Computing Technology and Science (CloudCom 2013), Bristol, UK, 2–5 December 2013; pp. 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sateesan, A.; Vliegen, J.; van der Leest, V.; Cmar, R. Hardware-oriented optimization of Bloom filter algorithms and architectures for ultra-high-speed lookups in network applications. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2022, 94, 104619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Yao, Y.; Berry, M.; Qi, H.; Cao, Q. Frequent traffic flow identification through probabilistic Bloom filter and its GPU-based acceleration. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2017, 87, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durachman, Y.; Wahab, A.; Rahman, A. Blockchain and the Evolution of Decentralized Finance: Navigating Growth and Vulnerabilities. J. Curr. Res. Blockchain 2024, 1, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.P.; Priya, S.; Batumalay, M. Examining the Association Between Social Media Use and Self-Reported Social Energy Depletion: A Machine Learning Approach. J. Digit. Soc. 2025, 1, 216–229. [Google Scholar]

- Alamsyah, R.; Wahyuni, S. Quantifying the Financial Impact of Cyber Incidents: A Machine Learning Approach to Inform Legal Standards and Risk Management. J. Cyber Law 2025, 1, 264–281. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, R. Using Information Technology to Quantitatively Evaluate and Prevent Cybersecurity Threats in a Hierarchical Manner. Int. J. Appl. Inf. Manag. 2023, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, N.A.; Jasim, O.N. Firefly Algorithm-Optimized Deep Learning Model for Cyber Intrusion Detection in Wireless Sensor Networks Using SMOTE-Tomek. J. Appl. Data Sci. 2025, 6, 2127–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenus, L.; Hananto, A.R. Predicting User Engagement in E-Learning Platforms Using Decision Tree Classification: Analysis of Early Activity and Device Interaction Patterns. Artif. Intell. Learn. 2025, 1, 174–194. [Google Scholar]

- El Emary, I.M.M.; Sanyour, R. Examination of User Satisfaction and Continuous Usage Intention in Digital Financial Advisory Platforms: An Integrated-Model Perspective. J. Digit. Mark. Digit. Curr. 2025, 2, 114–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramlich, V.; Guggenberger, T.; Principato, M.; Schellinger, B.; Urbach, N. A multivocal literature review of decentralized finance: Current knowledge and future research avenues. Electron. Mark. 2023, 33, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, B.; Wahyuningsih, T. Navigating Financial Transactions in the Metaverse: Risk Analysis, Anomaly Detection, and Regulatory Implications. Int. J. Res. Metaverse 2024, 1, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, R.; Bachteler, T.; Reiher, J. Privacy-preserving record linkage using Bloom filters. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2009, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Huang, K.; Zhang, D.; Qin, Z. Accurate Counting Bloom Filters for Large-Scale Data Processing. Math. Probl. Eng. 2013, 2013, 516298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, X.; Shi, R.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, G. SEPSI: A Secure and Efficient Privacy-Preserving Set Intersection with Identity Authentication in IoT. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatsalan, D.; Christen, P.; Verykios, V.S. A Taxonomy of Privacy-Preserving Record Linkage Techniques. Inf. Syst. 2013, 38, 946–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkas, B.; Schneider, T.; Tkachenko, O.; Yanai, A. Efficient Circuit-Based PSI with Linear Communication. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT, Darmstadt, Germany, 19–23 May 2019; pp. 122–153. [Google Scholar]

- Simion, E.; Pătrașcu, A. Applied Cryptography and Practical Scenarios for Cyber Security Defense. UPB Sci. Bull. Ser. C 2013, 75, 131–142. [Google Scholar]

| Variant | Primary Use-Case | Strength | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Bloom Filter [1] | Static sets, minimal space | Very low memory cost | No deletion support |

| Counting Bloom Filter [5] | Dynamic sets with removal | Full deletion support | Higher memory cost due to counters |

| Spectral Bloom Filter [14] | Frequency estimation in data streams | Multiplicity estimates | Counter noise under high load |

| Scalable Bloom Filter [4] | Unknown or growing sets | Stable false-positive rate under expansion | Multiple internal layers |

| Partitioned Bloom Filter [16] | Cache-sensitive systems | Uniform and predictable memory access | Rigid segment structure |

| Blocked Bloom Filter [13] | High-performance routing and caching | Excellent cache locality | Requires careful block-size tuning |

| Cuckoo Filter [20] | Dynamic sets with low-latency removal | Constant-time deletion and good space usage | Relocation overhead under heavy occupancy |

| Quotient Filter [21] | Static sets with compact storage | Efficient space use and fast lookups | More complex structure and cluster handling |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gagniuc, P.A.; Păvăloiu, I.-B.; Dascălu, M.-I. Bloom Filters at Fifty: From Probabilistic Foundations to Modern Engineering and Applications. Algorithms 2025, 18, 767. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18120767

Gagniuc PA, Păvăloiu I-B, Dascălu M-I. Bloom Filters at Fifty: From Probabilistic Foundations to Modern Engineering and Applications. Algorithms. 2025; 18(12):767. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18120767

Chicago/Turabian StyleGagniuc, Paul A., Ionel-Bujorel Păvăloiu, and Maria-Iuliana Dascălu. 2025. "Bloom Filters at Fifty: From Probabilistic Foundations to Modern Engineering and Applications" Algorithms 18, no. 12: 767. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18120767

APA StyleGagniuc, P. A., Păvăloiu, I.-B., & Dascălu, M.-I. (2025). Bloom Filters at Fifty: From Probabilistic Foundations to Modern Engineering and Applications. Algorithms, 18(12), 767. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18120767