1. Introduction

Real-world problems in fields, such as bio-informatics, logistics, telecommunications, and others, are often modeled using graphs and solved with search for the shortest paths between node pairs of the graph [

1]. The shortest path problem has three main variations: finding the shortest path between two specific nodes, computing shortest paths from a single node to all other nodes (single-source shortest path, SSSP), and determining shortest paths between all node pairs (all-pairs shortest path, APSP). There are two fundamentally different approaches to solve the APSP problem. In the first one, we solve the SSSP problem for each node in the graph and combine the results, while in the second approach, we simultaneously construct shortest paths for all node pairs of the graph. In the first approach, usually a Dijkstra-like algorithm is used for graphs with non-negative edge weights. In this paper, we restrict ourselves to graphs with non-negative edge weights, leaving the treatment of negative weights for future work.

Probably the best known second approach is the Floyd–Warshall algorithm, which employs the dynamic programming technique. However, in both approaches, the key operation is a relaxation and it turns out that the time complexity of the solution is linear in the number of relaxation attempts. Consequently, the first approach proves to be more appropriate for sparse graphs and the second for dense ones.

In this paper, we study the feasibility of the second approach on sparse graphs, particularly disconnected directed graphs. In our approach, we propose first identifying strongly connected components of the graph, on each of which we then apply the “APSP algorithm” independently. This is reasonable, as within each strongly connected component, each pair of nodes is mutually reachable. To handle shortest paths between pairs of nodes in different components, we rely on a simple observation: if there is no path from an arbitrarily chosen node in the source component to an arbitrarily chosen node in the destination component, then relaxations can be safely skipped for all node pairs where the first node belongs to the source component and the second to the destination component.

The objective of this paper is first to present a new approach to solve the APSP problem and then empirically evaluate and compare it with the existing algorithms. Empirical evaluation is performed on artificially generated graphs (Erdős–Rényi method [

2,

3] and the Barabási–Albert method [

4]) and real-world graphs derived from practical datasets.

Section 2 reviews related work in all-pairs shortest path algorithms and it is followed by basic definitions. Our solution is presented in

Section 4 and evaluated in

Section 5.

Section 6 summarizes the results and research insights.

2. Related Work

The Floyd–Warshall algorithm [

5,

6] is a classic APSP solution using dynamic programming, performing

relaxation attempts on a graph with

n nodes. However, [

7] shows that many relaxations are unnecessary, and for complete directed graphs with uniformly distributed weights, their modified version runs in expected

time. Similarly, SmartForce [

8] achieves significant speedups by avoiding all other but a small fraction relaxation attempts. For graphs that are not complete or are sparse, the Rectangular Algorithm [

9] improves performance by blocking the distance matrix and skipping inactive regions. The Improved Floyd–Warshall algorithm [

10] further optimizes sparse graphs by dynamically maintaining reachability lists and prioritizing nodes with low in-/out-degree products, reducing iterations when the number in a graph is bigger the number of edges. All variants, however, retain the worst-case

time bound.

Another approach to solve the APSP problem is to solve the SSSP problem for each node in the graph (cf. [

11]). For graphs with

m edges, all of which have non-negative weights, Dijkstra’s algorithm [

12] solves the SSSP problem in

when a priority queue with amortized

deletes min operation and

other operations is used (e.g., [

13]). However, in practice, Dijkstra with pairing heaps [

14], despite weaker theoretical bounds, performs better. Returning to the APSP problem, the SSSP-based approach gives us

solution. Typically, on sparse graphs (e.g.,

), this approach is more efficient than Floyd–Warshall [

15]; however, for

, it matches Floyd–Warshall’s

. Finally for complete graphs, the Hidden Paths algorithm [

16] and Uniform Paths algorithm [

17,

18] give an expected

time bound (uniform weights on

).

3. Preliminaries

A directed graph G is an ordered pair , where V is a finite, non-empty set of nodes, and is a set of directed edges. We assume that for some integer n.

Each directed edge connects two nodes, called its end nodes, where u is referred to as the initial node, denoted by and v is referred as the terminal node, denoted by .

A path of length k in a directed graph is a sequence of pair-wise distinct nodes such that for each i where , the directed edge .

A directed graph, , is a sub-graph of a directed graph if and .

A node v is reachable from another node u in a directed graph if there exists a path from u to v. That is, there is a sequence of nodes such that , , and for each i where , the directed edge belongs to E.

A strongly connected component (SCC) of a directed graph is a maximal sub-graph —with respect to the number of nodes—such that for every pair of nodes , there exists a path from u to v and a path from v to u, meaning the nodes are mutually reachable.

Given a SCC

, the set of outgoing edges from

C is defined as

A directed graph is a directed acyclic graph (DAG) if it contains no directed cycles. That is, there does not exist a sequence of distinct nodes such that .

A topological ordering of a DAG is a linear ordering of its nodes such that for every directed edge , node u appears before v in the ordering.

A weighted digraph is a digraph with a weight function that assigns each directed edge a weight . A weight function w can be extended to a path by . A shortest path from s to d is a path in G whose weight is infimum among all paths from s to d. The distance between two nodes s and d, denoted by , is the weight of a shortest path from s to d in G.

For simplicity, we will refer to directed graphs simply as graphs throughout the rest of this paper.

4. Our Solution

We propose a shortest-path algorithm that exploits the strongly disconnected structure of graphs. The key idea is to decompose the graph into SCCs and process them in topological order, computing distances within each component and propagating paths across components only via outgoing edges.

4.1. Formal Definition of Shortest Path via SCCs

Let G be a directed graph partitioned into t strongly connected components , ordered topologically such that there are no edges from to for . Further, we denote the union by . Furthermore, for nodes let denote the length of shortest path from s to d containing only nodes from . We shorten the notation to .

Corollary 1. The length of the shortest path in G is

The following lemmata establish several structural properties of shortest paths with respect to the SCC decomposition, which will allow us to derive a recursive formulation for .

Lemma 1. Let be a SCC and let . Then the shortest path from s to d containing only nodes from lies entirely within .

Proof. Assume, for contradiction, that the shortest path from s to d exits , passing through a node . Since s can reach v, and v can reach d, by transitivity, this implies v is part of the same SCC as s and d. This contradicts the maximality of . Therefore, the shortest path must remain inside . □

Lemma 2. Let and let . Then the shortest path from s to d contains only nodes from and is of the formwhere is a shortest path containing only nodes from , the edge e is contained in , and is a shortest path containing only nodes from . Proof. First, since SCCs are topologically ordered, for the edge we have that and where . The first consequence of this observation is that the shortest path from s to d contains only nodes from . The second consequence is that the only way that to reach a later component from is to traverse an edge , and hence traverses an edge . Let denote the sub-path of from s to , and let denote the sub-path of from to d. Since a sub-path of a shortest path is also a shortest path, both and are shortest paths. Next, since starts and ends in , by Lemma 1 we have that contains only nodes from . Moreover, since starts outside the component , by Lemma 4 we have that lies entirely within . This completes the proof. □

Remark 1. Lemma 2 defines the structure of a shortest path , which permits us to perform relaxations only over .

Lemma 3. Let and let . Then .

Proof. Since for some , and the SCCs are topologically ordered, no node in is reachable from s. Hence, there is no path from s to d, and so . □

Lemma 4. Let s and d be nodes in . Then the shortest path form s to d containing only nodes from lies entirely within .

Proof. Since for some , and the SCCs are topologically ordered, no node in is reachable from s. Hence, there is no path from s that enters the component . Consequently, the shortest path from s to d lies entirely within . □

We now summarize these observations into the following theorem.

Theorem 1. Let s and d be nodes in , then using the above assumptions and notation, the length of a shortest path can be computed by the recurrence 4.2. Algorithm SCC

The algorithm SCC designed by Equation (

1) is a classical dynamic programming algorithm, which is also reflected in its structure. A naïve implementation in Algorithm 1 starts with a call of function SCC_Out on the input graph

G, which returns a topologically sorted list of SCCs associated with corresponding sets of outgoing edges (line 1). Next, we compute the base cases defined in the first line of Equation (

1) (lines 2–4). The remaining distances are computed using the second line and the third line of Equation (

1) (lines 6–16). The last line of Equation (

1) is reflected in line 6 of Algorithm 1. Note that the outer iteration loop goes over all destination nodes and the inner over all source nodes, which is counter-intuitive, but will prove useful later.

| Algorithm 1 Naïve APSP algorithm on input graph G using SCC decomposition |

| 1: | |

| 2: for to t do | |

| 3: APSP() | {Base case for each component} |

| 4: end for | |

| 5: | {Process in reverse topological order} |

| 6: for to 1 do | |

| 7: for each node do | |

| 8: for each node do | |

| 9: | {Initialize} |

| 10: for each edge do | |

| 11: | {Relaxation} |

| 12: end for | |

| 13: | {Third line of (1)} |

| 14: end for | |

| 15: end for | |

| 16: end for | |

The time complexity of Algorithm 1 depends on the number of relaxations performed in line 11. Consequently, we want to avoid unnecessary relaxation attempts, which happens, in particular, when the destination node d is not reachable from the source node s.

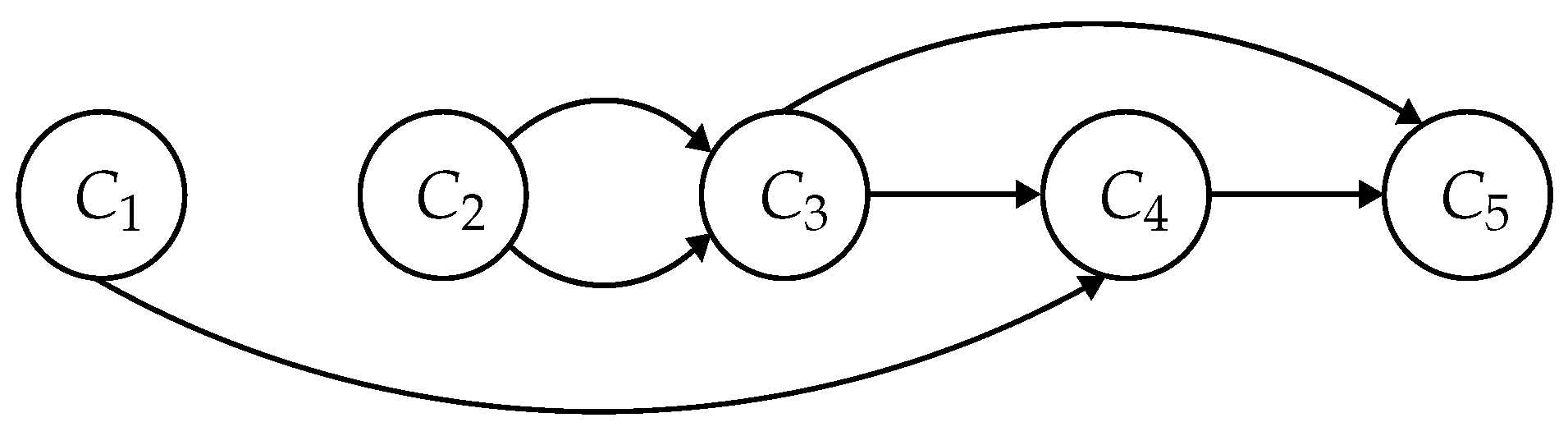

Such a situation occurs in

Figure 1, where destination nodes in components

and

are not reachable from source nodes in component

. Furthermore, destination nodes in component

are reachable from source nodes in

only through one edge in

. We observe that if one node of the component

is not reachable from the source node

s through an edge

, no node in

is reachable via

e. This brings us to the final version of our algorithm presented in Algorithm 2. To iterate only over the

-edges via which nodes in

are reachable the structure

in lines 8–14 is built. The relaxation in line 19 remains the same as in Algorithm 1.

We conclude the section with an analysis of the space complexity. First, if

or

, we extend the definition of

by setting

. Second, if both

, then by Lemma 4 and Corollary 1 we have

.

| Algorithm 2 APSP algorithm SCC on input graph G avoiding unnecessary relaxations |

| 1: | |

| 2: for to t do | |

| 3: APSP() | {Base case for each component} |

| 4: end for | |

| 5: | {Process in reverse topological order} |

| 6: for to 1 do | |

| 7: for to t do | |

| 8: | {Collect only edges via which is reachable} |

| 9: an arbitrary node in | |

| 10: for each edge do | |

| 11: if then | |

| 12: | {All nodes in are reachable from } |

| 13: end if | |

| 14: end for | { consist of -edges via which nodes in are reachable} |

| 15: for each node do | |

| 16: for each node do | |

| 17: | {Initialize} |

| 18: for each edge do | |

| 19: | {Relaxation} |

| 20: end for | |

| 21: | {Third line of (1)} |

| 22: end for | |

| 23: end for | |

| 24: end for | |

| 25: end for | |

Consequently, we can drop the exponent notation, yielding only , which in turn means that our algorithm needs to only store a single matrix of shortest path values. For this purpose, we can use a 2D array D[s,d].

Notably, in case of sparse graphs, in general, the majority of entries in the distance matrix

are

∞ corresponding to unreachability of a node

d from a node

s. To avoid storing these redundant entries, we, inspired by [

19], adopt a more space efficient storing of the matrix

—instead of a 2D array

D[,] we use a hashmap implementation of dictionary. The two operations on matrix

, assigning the value and reading the value, are implemented in straightforward way. The assignment is implemented as a combination of insertion and update, while the value reading uses the find operation, which in case of failure, returns

∞. Consequently, if the time complexity of our solution with a 2D array was

in the worst case, it stays the same but in the expected case. Moreover, we observe that since the value

is never increased, it is assigned value

∞ only once. However, this assignment is already implicitly done at the beginning since

is not inserted into a dictionary and hence takes no action and no time.

However, the space complexity changes from to , where is the number of pairs of nodes s and d, where d is reachable from s. This is optimal.

5. Evaluation

We empirically evaluated SCC algorithm against some other solutions, which the literature recognizes to be among the most efficient ones. This section first introduces the graphs on which the evaluation was performed. The test cases description is followed by brief description of implementation and concluded with the results and a brief discussion.

5.1. Test Cases

The tests were performed on generated graphs and graphs taken from real cases. Furthermore we used two different kinds of generated graphs. The first ones were generated using the Erdős–Rényi random graph model [

3]. The generation program takes two parameters

n, the number of nodes, and

, the graph density measure. The generated graph has nodes

and

edges. In a generation process, a list of all possible edges

is formed and randomly permuted. The first

m edges are then taken and assigned weights uniformly in the interval

, and they become edges of a generated graph. In our study, we focused on

, since for larger

, the number of SCCs decreases quickly to 1.

For the second kind of generated graphs, we used the Barabási–Albert approach with preferential attachment [

4]. This approach was designed to simulate real-world networks with heavy-tailed degree distributions and a hub-like structure. The generation procedure starts with a small initial complete undirected graph of

nodes. New nodes are added one by one, and each added node is connected to exactly

existing nodes. The probability of an existing node to be connected to the added node is proportional to its current degree. This results in a scale-free undirected graph with

n nodes and

edges. In the second step we produce a directed graph from the generated undirected graph by replacing each undirected edge

randomly with either

or

. Each edge is in final step assigned a weight drawn uniformly from the interval

.

For the graphs from the real-world, we used the

Stanford Large Network Dataset Collection (SNAP) [

20]. In particular we concentrated on

Internet peer-to-peer networks collection of graphs modeling the Gnutella file-sharing system [

21]. The nodes in these graphs represent the hosts of the Gnutella networks, while edges represent connections between the hosts: the directed edge from node

u to node

v indicates that host

u reports to host

v as a neighbor. The graphs are directed and sparse, with several thousand nodes and edges. We used seven out of the nine graphs in the collection as test cases (see

Table 1). The two omitted graphs were too big to be processed.

The final step is similar as before and assigns a uniform random weight of to each edge. These real-world graphs allow us to evaluate the behavior of our algorithm under realistic network structures that exhibit non-random, small-world, and scale-free properties.

5.2. Algorithm Implementation and Testing System

We implemented the function SCC_Out by slightly adapting the Tarjan’s algorithm for searching SCCs [

22,

23]. Briefly, the original algorithm applies a depth-first search to find cycles in a graph as they are bases for

components. In turn, an edge that is part of a cycle becomes part of an appropriate

, while the remaining edges belong to one of

. Consequently the adapted algorithm in linear time returns topologically sorted list of pairs

.

To compute APSP distances within each component

we decided to use the Tree algorithm presented in [

7].

The evaluated algorithms and graph generation algorithms were implemented using C/C++, and compiled using GCC version 13.1.0. with no compilation switches. Experimental evaluations were conducted on a computer with an Apple M2 processor, 8 GB of RAM, and running macOS Sequoia 15.3.1. For each combination of parameters, we generated three independent graph instances and reported the average execution time, measured in elapsed real-time (in seconds). Detailed execution times for all algorithms and structural properties for all graph instances can be found in

Appendix A.

5.3. Results

This section presents the empirical results of the APSP algorithm evaluations across three distinct graph types: Erdős–Rényi, Barabási–Albert and Gnutella. We compared our SCC algorithm with Floyd–Warshall (FW) [

5,

6], Dijkstra [

12], Hidden Paths (Hidden) [

16], Uniform Paths (Uniform) [

17,

18], Tree [

7] and Improved Floyd–Warshall algorithm (Toroslu) [

10].

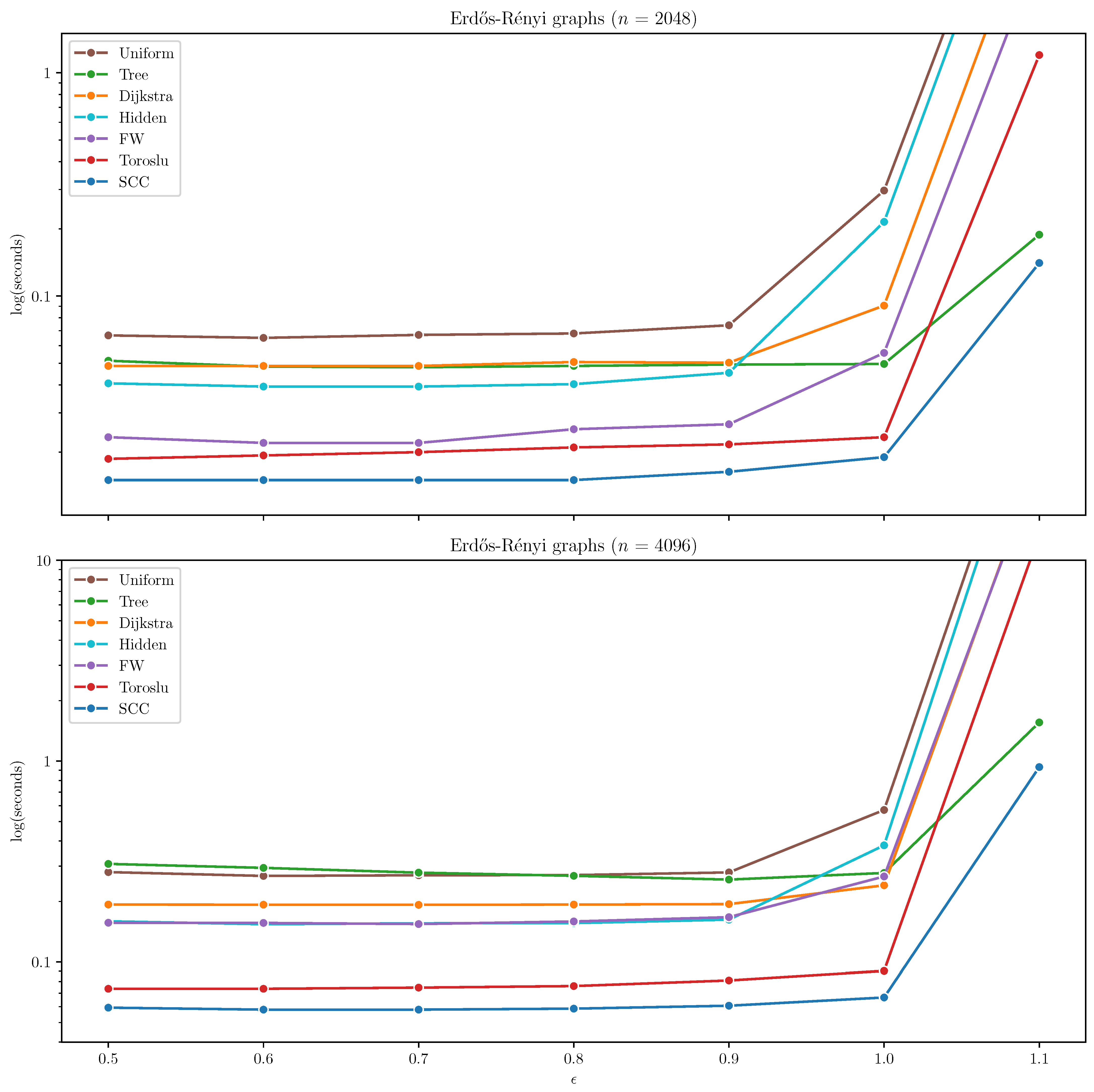

Erdős–Rényi Graphs

On Erdős–Rényi graphs, the SCC algorithm consistently outperformed all other algorithms by a significant margin across both tested graph sizes (

and

). The Toroslu algorithm demonstrated competitive performance for lower edge densities (

), but its scalability deteriorated noticeably when

, where execution times increased sharply. In contrast, SCC maintained stable and efficient runtimes even as both the graph size and density increased. The results on Erdős–Rényi graphs are presented in

Figure 2.

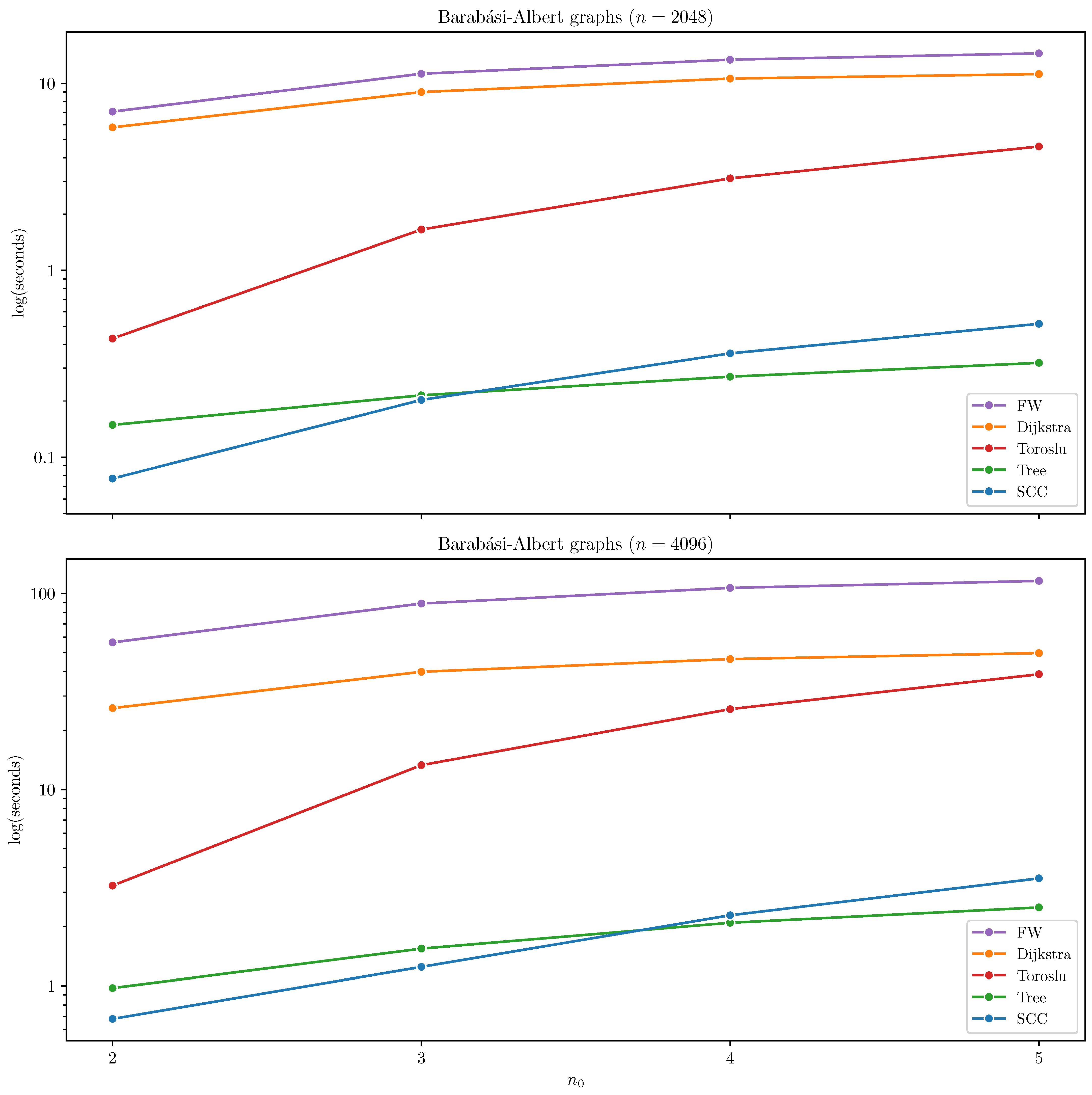

Barabási–Albert Graphs

In the case of Barabási–Albert graphs, Tree and SCC outperformed all other algorithms. SCC demonstrated particularly strong performance in sparser configurations with

and

, where the graph naturally fragments into smaller strongly connected components that can be efficiently processed independently. However, as the

increases to

and

, the largest strongly connected component begins to dominate the graph, often encompassing most of its nodes. In these denser configurations, the benefits of component decomposition diminish, and the overhead introduced by SCC becomes more pronounced. Consequently, Tree outperforms SCC in such cases. The results are summarized in

Figure 3, where algorithms with excessive runtimes are omitted for clarity (Hidden and Uniform).

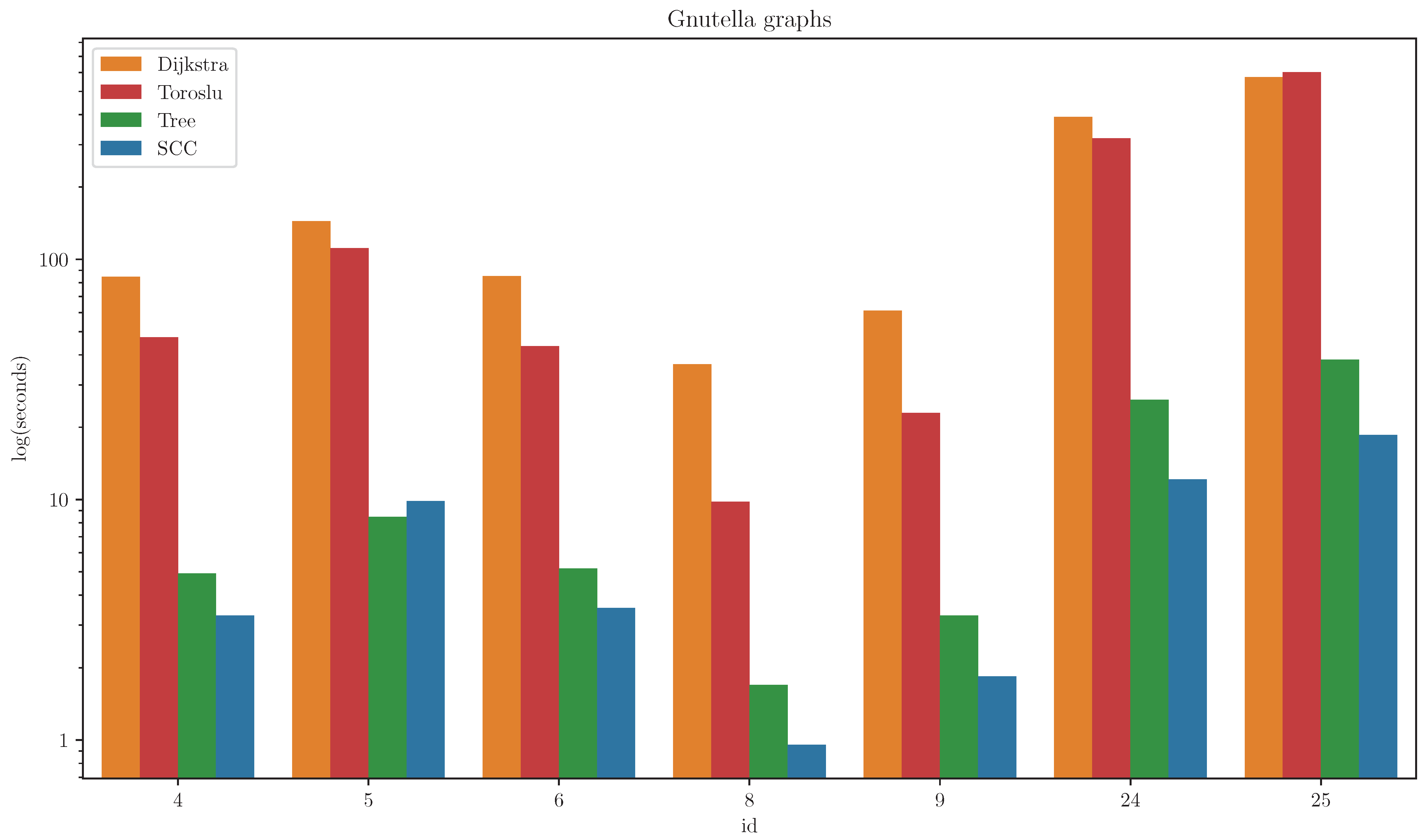

Gnutella Graphs

On the Gnutella peer-to-peer network graphs, the SCC algorithm achieved the best performance on all but one graph, on which the Tree algorithm outperformed it. The results are presented in

Figure 4. For clarity, algorithms with significantly higher runtimes are omitted from the figure (Hidden, Uniform, FW).

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed a new APSP algorithm specifically designed for disconnected graphs scenarios where classical approaches are often inefficient. Our solution combines well-established shortest path techniques with graph decomposition into SCCs and applies selective inter-component relaxations. Consequently, our approach significantly reduces redundant computations and leverages graph structure to improve runtime. A key feature of our approach is that relaxation is only performed between node pairs for which reachability is established—that is, only when intermediate distances are finite. This selective processing significantly reduces computational overhead, particularly in sparse topologies where many node pairs are disconnected. As a result, the algorithm eliminates redundant updates on unreachable paths, leading to substantial performance gains.

We note that the algorithm does not improve the theoretical worst-case bound . In the ill-formed case where the decomposition produces two strongly connected components, and , and every vertex in has an outgoing edge to every vertex in , the number of outgoing edges becomes , where denotes the number of vertices in . Under this configuration, the number of relaxation operations can approach . However, by applying a simple heuristic that detects when the number of outgoing edges becomes too large, the overall complexity can be reduced to . Thus, while the algorithm performs efficiently on sparse and disconnected graphs, its asymptotic upper bound in the worst case remains the same as that of the classical Floyd–Warshall algorithm.

The impact of this work lies in offering a practical and efficient alternative for APSP computation in domains where sparse, modular, or disconnected graphs naturally arise—such as social networks, dependency graphs, and biological networks. Future directions of research include formalizing the expected complexity in various graph models, validating the approach on real-world datasets.