1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of Earth observation technologies, high-resolution remote sensing imagery has become an indispensable data foundation for numerous fields including environmental monitoring, urban planning, and national defense security [

1,

2]. Among these, object detection—as the core technology for automatically identifying and locating objects of interest within vast image datasets—directly impacts the efficiency and accuracy of information extraction. Its performance remains a long-standing research focus and challenge in this domain [

3,

4].

Although deep learning-based object detection models, particularly single-stage detectors, have achieved remarkable success in natural image domains [

5], their direct application to remote sensing imagery remains fraught with significant challenges. This stems primarily from the inherent characteristics of remote sensing images: First, the background exhibits high complexity with numerous ground object types, often causing objects to be obscured by vast quantities of similar objects or intricate textures, resulting in insufficient feature discriminability; second, the extreme diversity in object scales—where large facilities spanning hundreds of pixels coexist with small vehicles comprising only tens of pixels—places high demands on the model’s feature extraction and multi-scale perception capabilities. Finally, the pronounced class imbalance issue makes it difficult for models to adequately learn the features of minority classes [

6,

7].

Currently, although researchers have proposed a series of improvement methods from different perspectives to address these challenges, existing studies tend to focus on optimizing individual components of detection networks in isolation, such as feature extraction, regression strategies, or activation functions [

8]. This research paradigm largely overlooks the potential synergistic effects among components within the network, failing to establish a coordinated, mutually reinforcing optimization mechanism at the system level. This has become a critical bottleneck limiting further improvements in model performance.

Based on this, this paper proposes an object detection algorithm named AFDNet. Its core concept lies in transcending traditional isolated optimization approaches by constructing an internal collaborative evolution mechanism. This mechanism aims to promote mutual reinforcement and co-optimization among the network’s three core components—feature perception, bounding box regression, and nonlinear transformation—during training, forming a powerful internal optimization cycle. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) Introduces a dual-channel–spatial-perception module that integrates contextual information from both spatial and channel dimensions through parallel attention paths, adaptively enhancing key object features while effectively suppressing complex background interference.

(2) Designs a dynamic bounding box optimization module that significantly improves localization accuracy and regression stability for multi-scale objects by incorporating distance-aware and scale-normalization strategies.

(3) A Gaussian adaptive activation unit is introduced, offering superior nonlinear fitting capabilities while maintaining computational efficiency, thereby enhancing the model’s representation of fine-grained features.

(4) The comprehensive experimental results on the public remote sensing datasets RSOD and NWPU VHR-10 show that AFDNet is significantly superior to the existing mainstream methods in many key indicators such as the mAP@50 and F1-Score, which fully verifies the effectiveness of the co-evolution mechanism and the advanced nature of the proposed algorithm.

This study proposes a novel approach to address the aforementioned challenges by establishing an internal co-evolution mechanism. The following sections will provide a detailed discussion on the specific design and implementation of the AFDNet algorithm, experimental validation, and analysis of results.

3. Algorithm Model

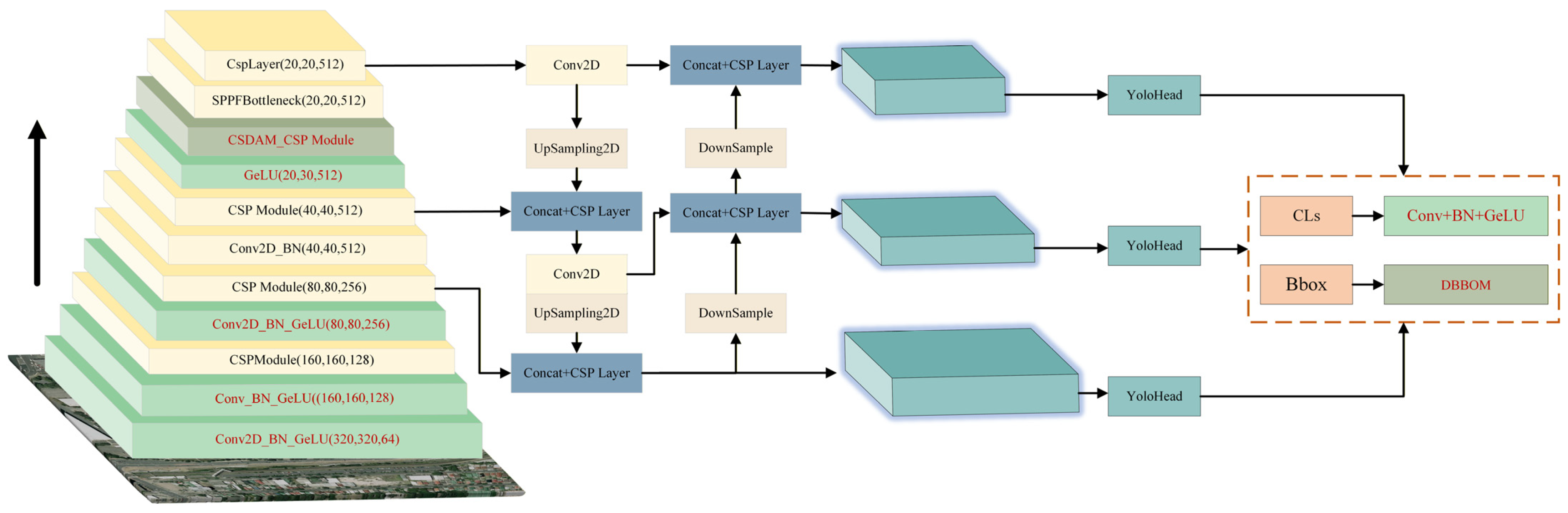

The overall architecture of the AFDNet algorithm is shown in

Figure 1. Following the general design paradigm of single-stage detectors, it primarily consists of three components: the backbone network, the Feature Pyramid Network (Neck), and the detection head. The core of this algorithm lies in the objected design and optimization of the backbone network and detection head through a collaborative evolution mechanism.

Backbone: The backbone is responsible for extracting multi-level feature representations from input images. This algorithm adopts a CSPDarknet-based structure as its foundation, integrating CSDAM and GeLU to enhance its feature extraction capabilities. The network input size is 640 × 640 × 3. Through convolution and downsampling operations, it progressively generates feature maps at different scales (e.g., 160 × 160, 80 × 80, 40 × 40, and 20 × 20), providing foundational features for subsequent multi-scale detection.

Feature Pyramid Network: The Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) receives outputs from the backbone network, fusing features from different levels to enhance the model’s detection capability for multi-scale objects. This algorithm employs the Path Aggregation Network (PANet) structure in this component. By utilizing bidirectional pathways (top-down and bottom-up) combined with lateral connections, this architecture effectively merges deep semantic information with shallow localization information, constructing an enhanced multi-scale feature pyramid (P3, P4, and P5).

Detection Head: The detection head receives multi-scale features from the feature pyramid and performs the final classification and localization tasks. This algorithm employs a decoupled design for the detection head, comprising two independent branches.

Classification Branch (Cls): This branch consists of Conv + BN + GeLU operations and is responsible for predicting the confidence scores of object categories contained within each anchor box.

Regression Branch (Bbox): This branch integrates DBBOM to predict the precise location and dimensions of the object’s bounding box.

Through deep feature extraction from the backbone network, multi-scale information fusion via the feature pyramid, and precise classification and localization by the detection head, this architecture constructs a comprehensive co-evolutionary detection framework. It provides robust technical support for object recognition in complex remote sensing scenarios.

3.1. Channel–Space Dual-Perception Module

In remote sensing image object detection, complex terrain backgrounds often intertwine with key objects, posing a severe challenge to the model’s discrimination capabilities. Traditional attention mechanisms typically employ serial structures or simple parallel approaches, struggling to fully capture the deep interactions between the channel and spatial dimensions. Furthermore, these methods often normalize attention weights using the softmax function, which is prone to vanishing or exploding gradients when encountering extreme input values, thereby limiting the model’s convergence stability and robustness. To overcome these limitations, we designed the Channel and Spatial Dual-Attention Module (CSDAM). Through a parallel dual-path architecture and an innovative feature fusion mechanism, CSDAM achieves the precise enhancement of key features while effectively suppressing background interference.

While preserving the efficiency of lightweight attention mechanisms, this module achieves performance breakthroughs by reconstructing feature interaction mechanisms. Compared to classical methods like CBAM, CSDAM employs a collaborative attention paradigm based on batch normalization (BN), establishing a dynamically coupled weight generation mechanism between the channel and spatial dimensions.

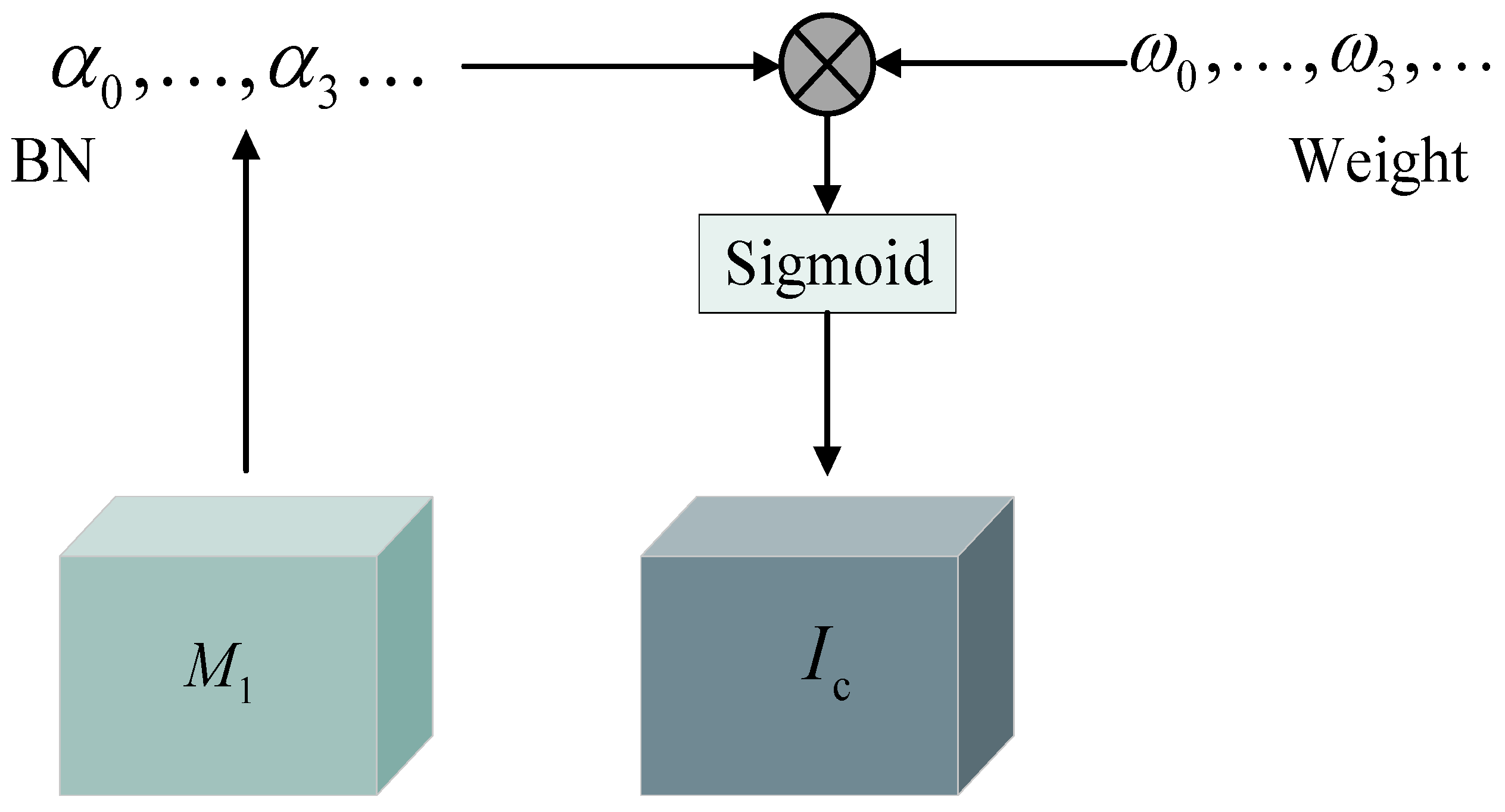

In the channel attention branch, the module innovatively utilizes the scaling factor inherent in the batch normalization operation to characterize the importance of each channel. The magnitude of this factor is learned during training, and its physical meaning is to measure the degree of variation in the corresponding channel features across batches of data. The batch normalization operation itself is defined as shown in Equation (1).

The channel attention sub-module, as shown in

Figure 2, serves as the scaling factor for each channel. It takes the input feature map as the input and outputs the feature map as shown in Equation (2).

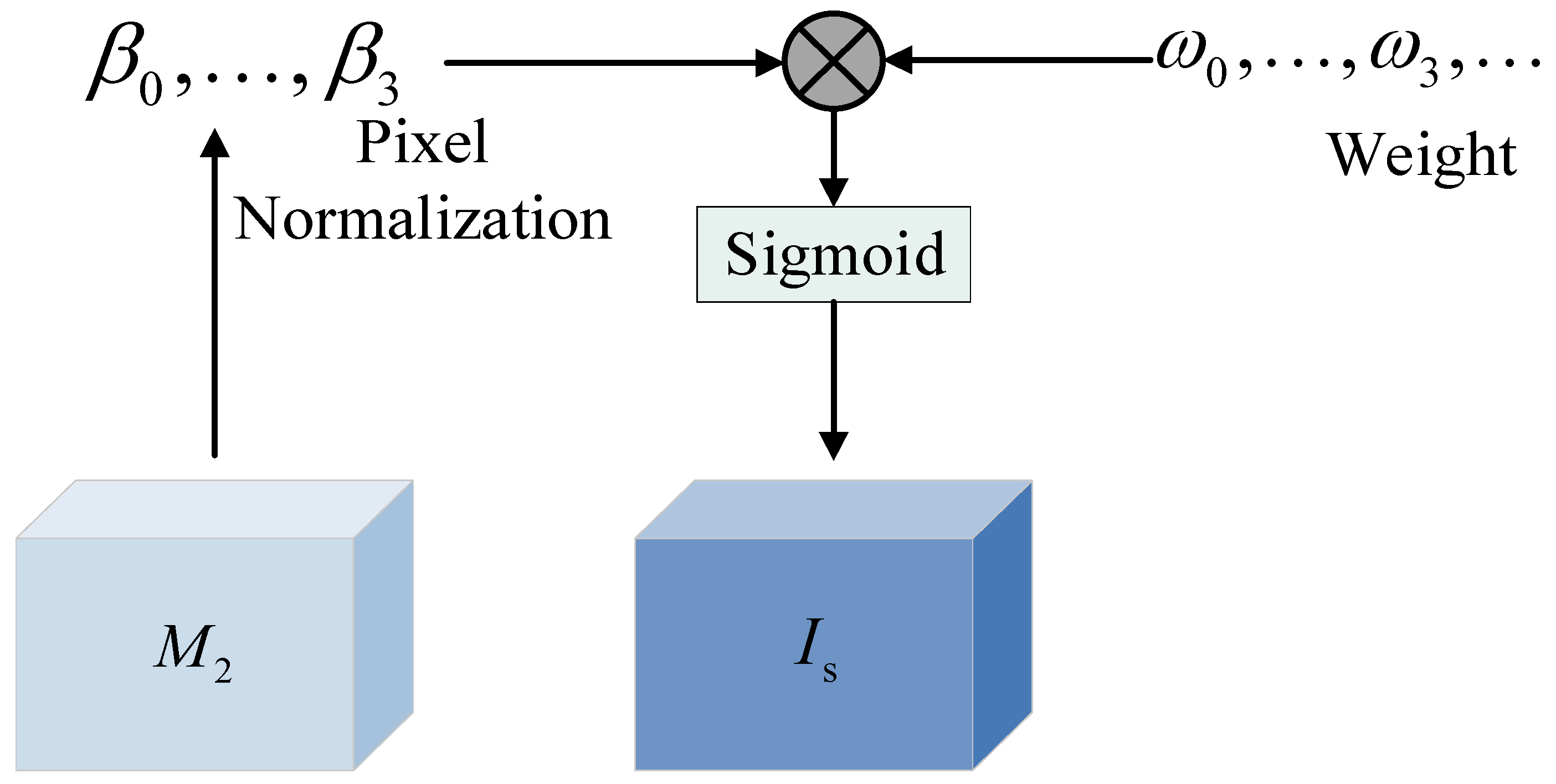

In the spatial attention branch, we extend the normalization concept by evaluating the importance of each position in the feature map space. This branch first processes the input features through a standard convolutional layer to obtain the intermediate feature

. Subsequently, it applies batch normalization to the spatial dimension and generates spatial attention weights via the sigmoid function with pixel normalization, as shown in Equation (3). The pixel attention map is illustrated in

Figure 3.

denotes batch normalization in the spatial dimension, and

represents the convolutional layer weights.

This parallel fusion mechanism, combined with a weight generation strategy based on batch-normalized statistics, enables the CSDAM to reliably enhance key features and suppress background interference while maintaining lightweight computational properties.

3.2. Bounding Box Regression Optimization Module

The performance of object detection largely depends on the accuracy of bounding box regression. Traditional IoU and its variants face significant challenges when handling extreme scale variations and complex scene distributions in remote sensing images: on one hand, training data inevitably contains numerous low-quality samples, and traditional geometric penalty mechanisms excessively amplify the loss weights of these samples, causing the model optimization direction to deviate; on the other hand, the enormous scale differences make it difficult for traditional methods to establish balanced regression gradients across objects of different sizes.

To address this issue, we propose the dynamic bounding box optimization module (DBBOM). This module significantly enhances the accuracy and robustness of bounding box regression by establishing a synergistic mechanism that is both distance-aware and scale-adaptive. Unlike traditional static loss functions, DBBOM introduces a dynamic weight adjustment strategy, enabling the model to adaptively shift its regression focus based on object characteristics.

The core innovation of DBBOM lies in constructing a dual-attention mechanism: the distance attention module and the scale-aware module. The distance attention module dynamically adjusts regression weights for samples at different positions by establishing a spatial relationship model between the predicted boxes and ground-truth boxes. This mechanism is represented as shown in Equation (4).

Among these,

is the constructed distance attention mechanism, whose calculation method is shown in Equation (5).

This design embodies three theoretical advantages. First, the distance attention weight is introduced as a dynamic gradient scaling factor, drawing motivation from established loss modification techniques like Focal Loss, which prioritizes hard or misclassified samples, and the -scaling factor in IOU-based losses that smooths the loss for small gradients. Specifically, our serves as an adaptive mechanism to amplify the prediction gradient of samples with moderate optimization potential (i.e., those that are “average quality” or “less confident”), guiding the model to focus effectively on these challenging yet trainable predictions. This mechanism is theoretically supported as a way to achieve balanced sample optimization, preventing the gradient signal from being dominated by already high-quality or very low-quality samples. Second, by setting the denominator term as a gradient clipping mechanism, it mitigates the impact of abnormal gradients on training stability. Finally, when prediction boxes exhibit high overlap with object boxes, the mechanism automatically enhances the optimization of center-point distances, enabling intelligent switching between different regression stages. and denote the minimum bounding box sizes, while * indicates its separation from the computational graph to prevent convergence slowdowns.

During training, this module exhibits unique adaptive properties: for high-quality anchor boxes, term approaches zero, naturally reducing the influence of distance attention weights; whereas for average-quality samples, the amplification effect of ensures that the model receives sufficient optimization signals. This dynamic balancing mechanism effectively mitigates the issue of low-quality samples dominating the training process, significantly enhancing the model’s generalization capability in complex remote sensing scenarios.

This module forms deep synergy with the previously mentioned CSDAM feature enhancement module. The refined feature representations provided by CSDAM lay a solid foundation for bounding box regression, while this module further optimizes regression accuracy through an intelligently weighted loss function. The two modules mutually reinforce each other, constituting a complete co-evolutionary system: high-quality features generate more accurate initial predictions, and precise regression loss in turn guides the optimization direction of the feature extraction network.

3.3. Gaussian Linear Error Module

In deep neural networks, activation functions serve as the core components introducing nonlinearity, and their design decisively impacts the model’s representational capacity and training stability. From traditional ReLU to Swish and Mish, researchers have focused on enhancing network expressiveness by refining activation functions. However, existing methods still face significant limitations when handling complex feature patterns in remote sensing images: the hard zero boundary of the ReLU function leads to dead neuron issues; functions like Swish mitigate gradient vanishing but exhibit high computational complexity; and while the GeLU function performs exceptionally well in Transformers, it struggles to be efficiently deployed in computationally intensive detection tasks.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes the Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GeLU) based on the Gaussian error function. The core idea of this unit is to integrate the concept of stochastic regularization into the activation process, achieving more elegant nonlinear transformations through probabilistic modeling. The complete mathematical definition of GeLU is shown in Equation (6).

Here,

denotes the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution, whose specific expression is given by Equation (7).

Here,

is the Gaussian error function. From a probabilistic perspective, this function can be further expressed in the expectation form, as shown in Equation (8):

where

and

represent the mean and standard deviation of the normal distribution, respectively. Considering the difficulty of directly computing the above integrals, we derive two efficient computational approximations, as shown in Equation (9).

A more concise sigmoid approximation is derived, as shown in Equation (10).

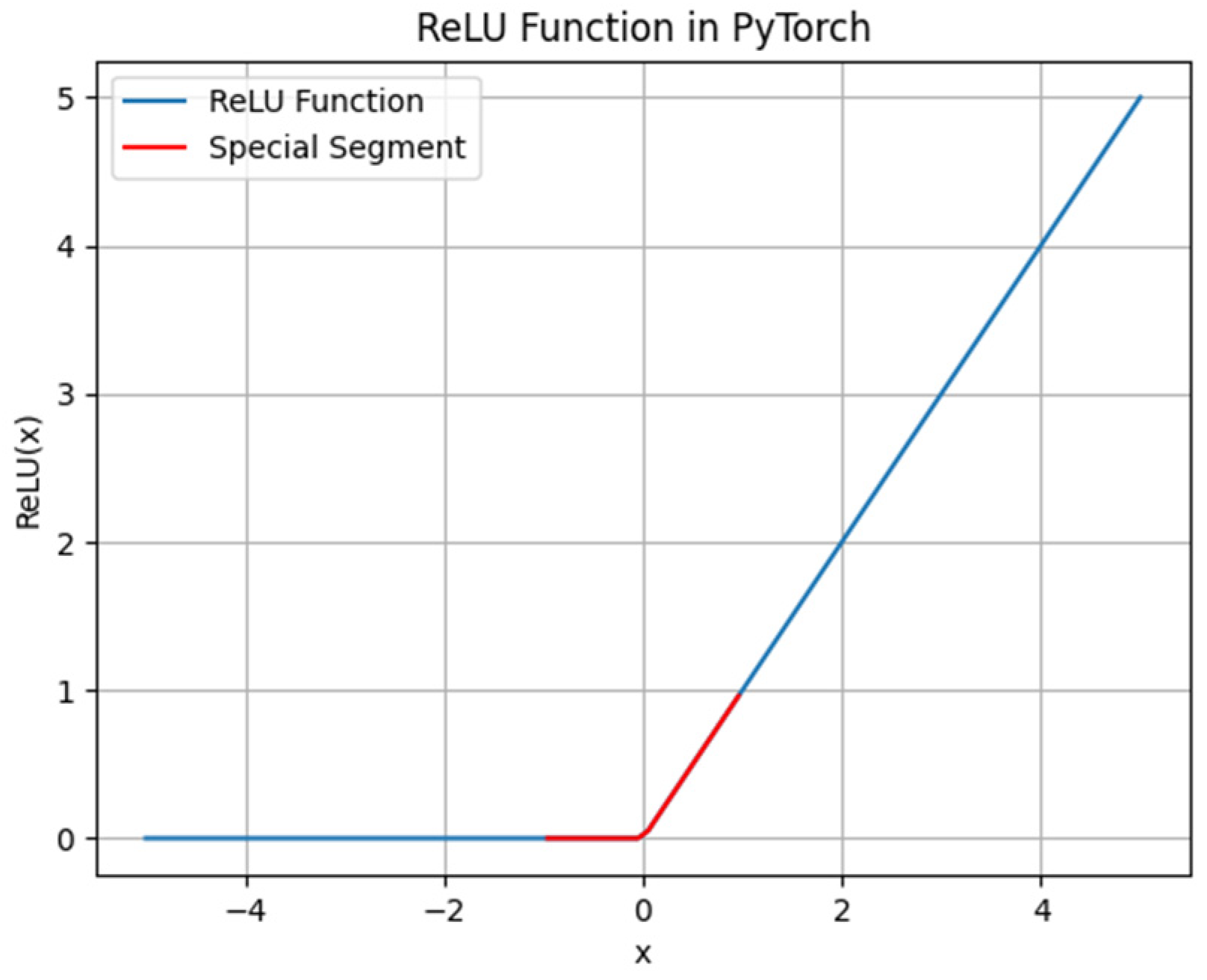

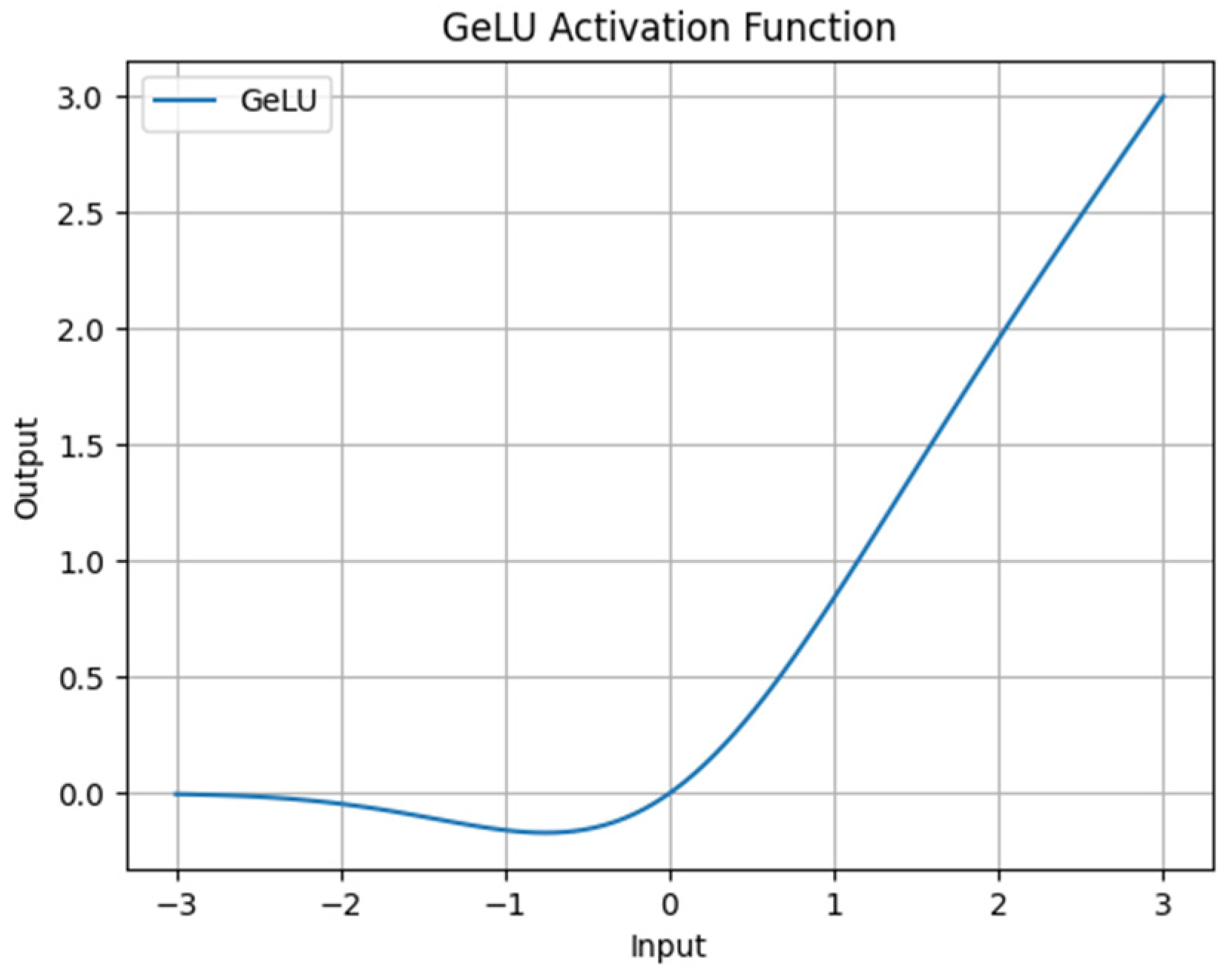

Compared to the ReLU function, the GeLU function possesses a non-zero gradient in the negative value region, thereby avoiding the issue of dead neurons. Additionally, GeLU exhibits greater smoothness near zero than ReLU, facilitating easier convergence during training. It is worth noting that GeLU involves more complex computations, thus requiring greater computational resources. Graphs of the ReLU and GeLU functions are shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

The core advantages of GeLU lay its effectiveness in remote sensing object detection. Its design concept based on probability distribution makes the function maintain a non-zero gradient in the negative region, which effectively alleviates the problem of Neuron Dropout. At the same time, the continuous differentiability of the function near the origin ensures the stable propagation of the gradient. These excellent nonlinear fitting and activation characteristics enhance the ability of the model to extract detailed information under low-resolution or weak object conditions and achieve deep collaboration with the CSDAM feature enhancement module and the dynamic bounding box optimization module, jointly building a high-performance detection framework.

Within AFDNet’s co-evolutionary framework, GeLU serves as a foundational component. This unit forms a deep complementarity with the CSDAM: GeLU’s smooth nonlinear transformation provides a robust foundation for feature enhancement, while its stable gradient flow ensures training convergence for the dynamic bounding box optimization module.

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Experimental Setup

Table 1 details the hardware and software configurations used in this experiment. The experiment employs a GPU setup, NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPUs (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, United States), providing a robust computational foundation for model training. The software environment runs on the Windows 11 operating system, utilizing the PyTorch 2.1.0 and CUDA 12.1 deep learning frameworks, with data analysis performed using libraries such as Matplotlib 3.7.1. Regarding training parameter settings, input image dimensions were uniformly adjusted to 640 × 640 pixels. The initial learning rate was set to 0.01, employing the Adam optimizer with a batch size of four and a training cycle of 100 epochs.

In terms of implementation details, the AFDNet model is built upon the PyTorch framework, adopting the standard workflow of single-stage detectors. This includes a backbone feature extraction network, a multi-scale feature fusion module, and a detection head. While the foundational implementation references industry-recognized mature design paradigms to ensure fair comparisons, the core contribution of this paper lies in proposing a collaborative evolution mechanism and instantiating three key modules: CSDAM, DBBOM, and GeLU. These modules constitute the core innovation of AFDNet, whose design philosophy is versatile enough to be independently transferred to other detection frameworks. A progressive learning strategy is employed during training, dynamically adjusting loss function weights to balance classification and regression tasks, ensuring the three innovative modules can be co-optimized.

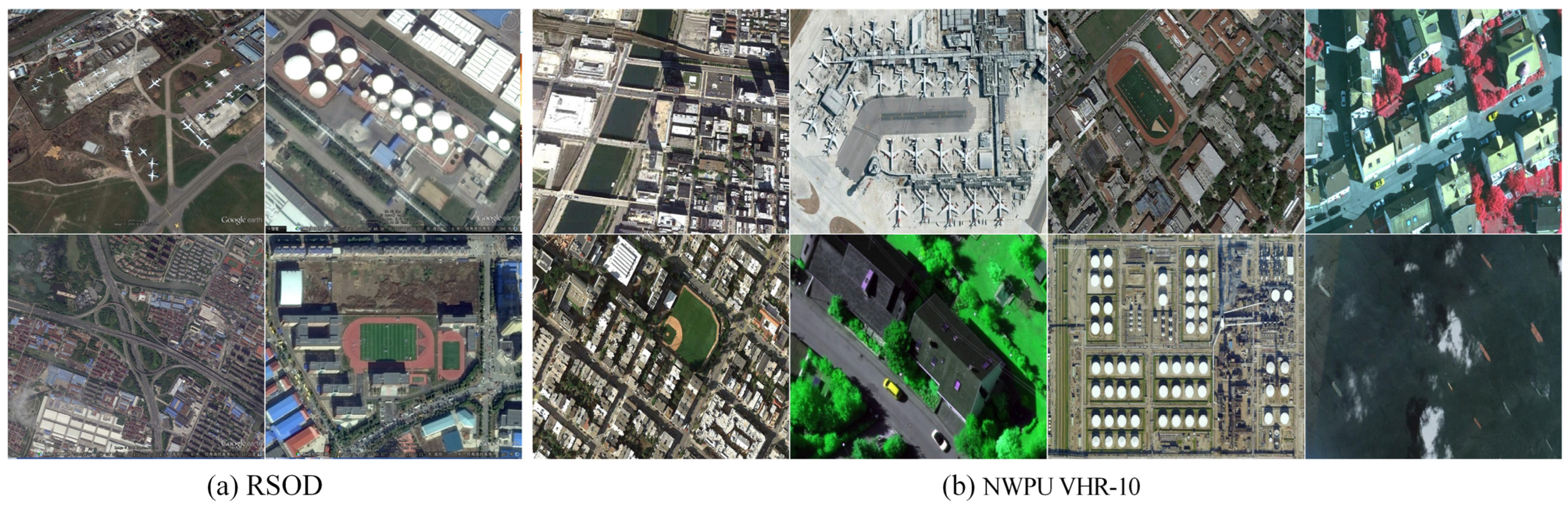

4.2. Dataset Introduction

The RSOD dataset is an open-source dataset for object detection in remote sensing images, which has attracted significant attention due to its substantial number of image samples and diverse object categories. It covers four representative types of ground objects: aircraft, oil tanks, overpasses, and playgrounds, providing researchers with abundant resources for training and testing. Specifically, the dataset includes approximately 446 aircraft images (containing 4993 objects), 165 oil tank images (containing 1586 objects), 176 overpass images (containing 180 objects), and 189 playground images (containing 191 objects).

To enable a more comprehensive evaluation of algorithm performance, this paper also utilizes the NWPU VHR-10 dataset. As a highly influential benchmark in the field of remote sensing, it contains 10 common object categories: aircraft, ships, oil tanks, baseball fields, tennis courts, basketball courts, athletic tracks, harbors, bridges, and vehicles. The dataset consists of over 800 high-resolution remote sensing images, including 650 images with objects and 150 background images. With a wider variety of object types and more complex scenes, it is often used to validate the generalization capability and robustness of object detection algorithms in diverse remote sensing scenarios.

Figure 6 shows sample remote sensing images from both datasets, visually illustrating the characteristics of typical ground objects such as aircraft, oil tanks, overpasses, and playgrounds in remote sensing imagery. Together, the RSOD and NWPU VHR-10 datasets provide essential support for remote sensing object detection research—the former focuses on the fine-grained detection of specific categories, while the latter offers broader category coverage and scene diversity.

4.3. Indicator Analysis

To comprehensively evaluate model performance, this paper employs seven key metrics that are widely recognized in the object detection field, covering both detection accuracy and computational efficiency.

mAP (mean average precision) serves as a key metric for evaluating a model’s overall performance in multi-class object detection. This paper employs mAP@50, which represents the mean average precision value at an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5. This metric first calculates the average precision (AP) for each class, then averages all class AP values to obtain mAP@50.

Precision measures the proportion of True Positive samples correctly predicted as positive, reflecting the reliability of detection results.

Recall evaluates a model’s ability to identify positive samples, calculated as the proportion of correctly detected positives relative to all true positives.

The F1-Score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced and unified assessment of both.

The evaluation metric formulas are shown in

Table 2.

FLOPs (Floating Point Operations) quantify the computational complexity of a model by measuring the total number of Floating Point Operations required for a single forward pass. This metric reflects the theoretical computational cost and is hardware-independent, making it crucial for evaluating model efficiency and suitability for resource-constrained environments.

The number of parameters indicates the model’s scale and complexity, representing the total learnable weights in the network. Fewer parameters generally suggest lower memory requirements and reduced risk of overfitting, while more parameters may indicate higher model capacity.

FPS (Frames Per Second) measures the practical inference speed by counting how many images a model can process per second. This hardware-dependent metric is crucial for real-time applications and is significantly influenced by the implementation environment, including GPU capability and software optimization.

These metrics collectively provide comprehensive insights into both the detection performance and practical deployment potential of the evaluated models.

4.4. Comparative Experimental Analysis

The performance of the proposed AFDNet model was comprehensively evaluated through comparative experiments against several mainstream object detection models on the RSOD and NWPU VHR-10 datasets. The comparison included single-stage detectors (like the YOLO series and SSD) and Transformer-based detectors (DETR, RT-DETR).

Table 3 shows the performance comparison of various object detection models including AFDNet on the RSOD dataset. On the whole, the AFDNet algorithm shows a significant advantage, with 95.16% on the mAP@50 indicator, surpassing all other models, including the latest YOLO series (such as 92.91% of YOLOv10x and 93.26% of YOLOv11) and other high-performance detectors (such as 93.51% of RT-DETR). This shows that the AFDNet has the highest detection accuracy in the RSOD dataset. In terms of important detection accuracy indicators, AFDNet’s precision is as high as 93.57%, second only to YOLOv5x, and its recall also reaches 82.02%, which is the highest value in all models that list complete indicators, which means that it can find more targets. For the F1-Score of the comprehensive precision and recall rate, AFDNet also reached 85.50%, putting it in a leading position. It is worth mentioning that, while maintaining top performance, AFDNet ‘s GFLOPs (109.0) and Parameters/M (87.31) also have better balance than some high-precision models (such as YOLOX’s 281.97 GFLOPs and 99.11 M parameters). Although its FPS is 63.84, which is lower than the lightweight model, considering its huge lead on mAP@50, AFDNet provides the best precision–recall trade-off and highest detection accuracy in this dataset.

Table 4 summarizes the performance of each object detection model in the more challenging NWPU VHR-10 dataset. In this dataset, the AFDNet also performs well, especially in key detection accuracy and recall rate. With a mAP@50 value of 96.52%, AFDNet surpassed all the comparison models again, further verifying its superior generalization ability and robustness, even higher than RT-DETR (95.89%) and YOLOv11 (95.63%), which performed best on this dataset. In terms of detailed performance indicators, AFDNet shows the advantage of compaction: its recall reaches 92.89%, which is the highest value of all models that list the complete indicators, far exceeding other models (e.g., YOLOv11 is 86.41%), meaning that AFDNet has a very low missed detection rate in complex scenarios. At the same time, the precision of the AFDNet is as high as 95.42%, which ensures the high accuracy of the test results, and the F1-Score is also ranked first at 93.80%. This fully proves the powerful ability of AFDNet in accurately identifying and locating remote sensing image targets. In terms of computational overhead, AFDNet’s FLOPs (109.0) and Parameters/M (87.31) remain within a reasonable range, indicating that its high performance does not simply depend on the huge model volume. In summary, in the benchmark test of NWPU VHR-10, a high-resolution remote sensing target detection, AFDNet, is the best comprehensive performance algorithm, especially in ensuring high detection accuracy (mAP@50) while significantly improving the recall and F1-Score of the object.

On the whole, the significant advantages of AFDNet in all evaluation indicators verify the effectiveness of the co-evolutionary mechanism it adopts. It has successfully achieved a significant increase in the recall rate while maintaining high accuracy, breaking through the classic trade-off between the accuracy and recall rate in target detection. This breakthrough performance stems from the synergistic contribution of three core innovation modules: CSDAM strengthens feature representation, DBBOM optimizes bounding box regression accuracy, and the GeLU unit guarantees the nonlinear expression ability of the network.

4.5. Melting Analysis Experiment

In order to fully verify the independent contributions of the three core innovation modules of CSDAM, DBBOM, and GeLU proposed in this paper and their synergistic optimization effects, we use a general architecture of a single-stage detector as the baseline model and conduct a series of systematic ablation experiments on the RSOD and NWPU VHR-10 datasets. The results are presented in

Table 5 and

Table 6, respectively.

Table 5 shows the independent contribution and cumulative effect of the three core innovation modules, CSDAM, DBBOM, and GeLU, proposed in this paper on the RSOD dataset. Taking Step 1’s baseline model (mAP@50 is 90.64%) as a starting point, the gradual introduction of each module has brought continuous and significant performance improvements. Firstly, CSDAM (Step 2) is introduced to immediately increase the mAP@50 to 91.49% and recall to 1.70%, which verifies the efficiency of CSDAM in enhancing feature representation. On this basis, after further introduction of DBBOM (Step 3), mAP@50 jumped to 93.05%, a significant increase (+1.56%), which clearly shows the key role of DBBOM in optimizing target positioning accuracy. Finally, on the basis that the module combination has been improved, the nonlinear activation function is optimized. The results show that GeLU (Step 6) exceeds Swish (94.61%) and Mish (95.02%) with a 95.16% mAP@50 performance, which proves that GeLU provides the most stable and efficient nonlinear transformation. Finally, the synergy of the three modules makes the mAP@50 of AFDNet reach 95.16%, which is a significant improvement of 4.52% compared with the baseline model, which fully proves the effectiveness of all innovative modules and their strong optimization potential on the RSOD dataset.

Table 6 shows the ablation experimental results on the more challenging NWPU VHR-10 dataset, which further confirms the robustness of each module. Starting from the baseline model (Step 1, mAP@50 is 92.87%), the introduction of CSDAM (Step 2) brought an amazing performance improvement, mAP@50 reached 95.13% (+2.26%), while recall surged from 70.15% to 85.71%, highlighting the excellent ability of CSDAM to accurately recall targets in complex high-resolution remote sensing images. Subsequently, the integration of DBBOM (Step 3) further increased mAP@50 to 95.77% and recall to 89.18%, confirming the continuous optimization effect of DBBOM on the accuracy of bounding box regression. Consistent with the results of RSOD experiments, GeLU (Step 6) again outperformed Swish (96.24%) and Mish (96.43%), with a maximum mAP@50 performance of 96.52% when comparing the activation functions. This shows that GeLU can provide the most favorable nonlinear optimization while maintaining high positioning accuracy. In summary, the three innovative modules have formed a strong positive optimization closed-loop on the NWPU VHR-10 dataset, making the mAP@50 of the model stable to the optimal level of 96.52%, which verifies its excellent performance and complementary synergy in complex remote sensing target detection tasks.

Comprehensive analysis shows that CSDAM successfully enhances the discrimination of features; DBBOM focuses on optimizing the precise positioning of the target bounding box; and GeLU provides stable and efficient nonlinear support. These three innovative modules each play a unique and complementary key role. Their organic combination makes the performance of the entire detection system reach the optimal state, which fully proves the effectiveness and innovation of the proposed method.

4.6. Detection Effect

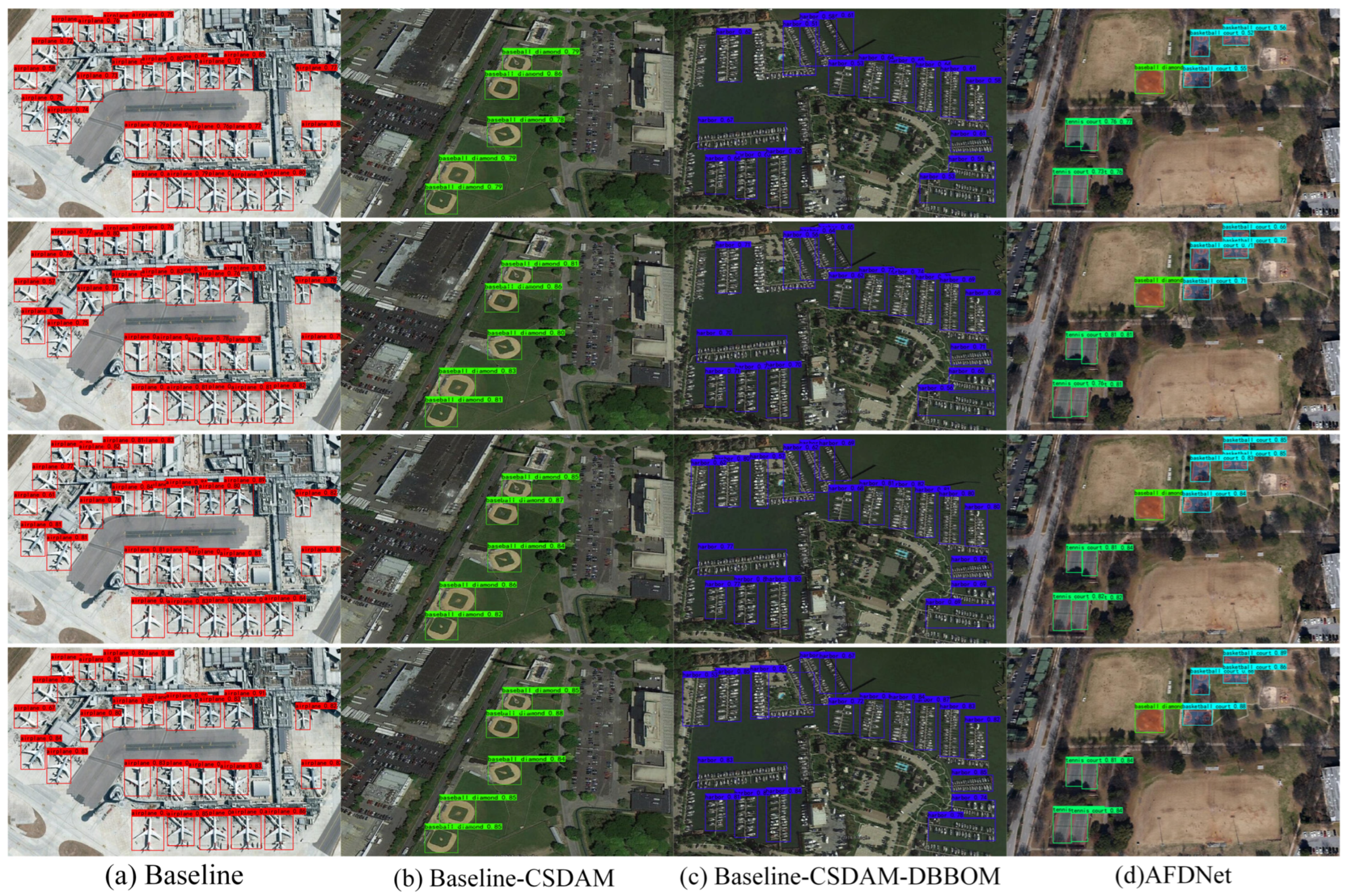

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 present the visual detection results of four ablation experiment models: (a) baseline, (b) Baseline-CSDAM, (c) Baseline-CSDAM-DBBOM, and (d) AFDNet.

Figure 7 showcases the detection performance on the RSOD dataset, demonstrating results across four typical categories: aircraft (red), oil tank (green), overpass (cyan), and playground (purple). The models’ detection capabilities for remote sensing objects of varying scales and shapes are clearly visible, with each category accurately annotated by bounding boxes of distinct colors.

Figure 8 showcases the detection performance on the NWPU VHR-10 dataset, demonstrating results across four categories: aircraft (red), baseball field (green), ship (blue), and tennis court (cyan/red). These visualizations provide an intuitive representation of the models’ actual performance in complex remote sensing scenarios, offering crucial visual references for subsequent quantitative analysis.