Abstract

We investigate and compare two versions of the Nelder–Mead simplex algorithm for function minimization. Two types of convergence are studied: the convergence of function values at the simplex vertices and convergence of the simplex sequence. For the first type of convergence, we generalize the main result of Lagarias, Reeds, Wright and Wright (1998). For the second type of convergence, we also improve recent results which indicate that the Lagarias et al.’s version of the Nelder–Mead algorithm has better convergence properties than the original Nelder–Mead method. This paper concludes with some open questions.

MSC:

65K10; 90C56

1. Introduction

The original Nelder–Mead (NM) simplex algorithm was constructed in 1965 by Nelder and Mead [1] as an improved version of the simplex method of Spendley, Hext and Himsworth [2]. During the almost six decades that have passed, the Nelder–Mead algorithm has became a truly popular and widely used method for the minimization problem

in derivative-free optimization (see, e.g., [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]).

In spite of its widespread use, only a few convergence results are known. They are of essentially two types. The first type of results are related to the convergence of function values at the vertices of the simplex sequence. They say nothing about the vertices. The most famous results of this type are due to Lagarias, Reeds, Wright and Wright [12]. The other type of results are related to the convergence of simplex vertices or simplices. The first result of this type is due to Kelley [13], who proved that under a certain (Armijo-type) descent condition, the accumulation points of the simplex sequence are critical points of f. Recent results on the convergence of the simplex sequence to a common limit point are given in papers [14,15,16].

Wright [17,18] raised several questions concerning the Nelder–Mead method:

- (a)

- Do the function values at all vertices necessarily converge to the same value?

- (b)

- Do all vertices of the simplices converge to the same point?

- (c)

- Why is it sometimes so effective (compared to other direct search methods) in obtaining a rapid improvement in f?

- (d)

- One failure mode is known (McKinnon [19])—but are there other failure modes?

- (e)

- Why, despite its apparent simplicity, should the Nelder–Mead method be difficult to analyze mathematically?

In fact, there are several recent examples that indicate different types of convergence behavior:

- The function values at the simplex vertices may converge to a common limit value, while the function f has no finite minimum and the simplex sequence is unbounded (Example 5 of [14]; Examples 1 and 2 of [15]; Example 4 of [20]).

- The simplex vertices may converge to a common limit point, but it is not a stationary point of f (McKinnon [19] and Example 3 of [15]).

- The simplex sequence may converge to a limit simplex of a positive diameter, resulting in different limit values of f at the vertices at the limit simplex (Theorem 1 of [21]; Example 4 of [14]; Examples 4 and 5 of [15]; Examples 1, 2 and 3 of [20]).

- The function values at the simplex vertices may converge to a common value, while the simplex sequence converges to a limit simplex with a positive diameter (Example of 5 [20]).

These examples are answering questions (a), (b) and (d) of Wright negatively.

There are several variants of the original Nelder–Mead method [1]. Here, we study two main versions of the Nelder–Mead algorithm: the ’original’ (unordered) method of Nelder and Mead [1] (Algorithm 1) and the ’ordered’ version of Lagarias, Reeds, Wright and Wright [12] (Algorithm 2). In Section 2, we introduce both algorithms, while Section 3 contains their matrix representations. In Section 4, we study the connection and spectral properties of these matrices. In Section 5, we prove convergence of the function values at the simplex vertices for both algorithms. These results are more general than those of Lagarias et al. [12], while their proof is quite simple.

In Section 6, we study the convergence of the generated simplex sequence. Here, we give necessary and sufficient conditions for the convergence of the simplex sequence (for both algorithms). This relates the convergence to the convergence of an infinite matrix product. We pay particular attention to the case when the simplex sequence converges to a common limit point. The results show why the convergence problem (questions (c) and (e) of Wright) is difficult. This paper closes with computational results, conclusions and open questions.

2. Two Versions of the Nelder–Mead Method

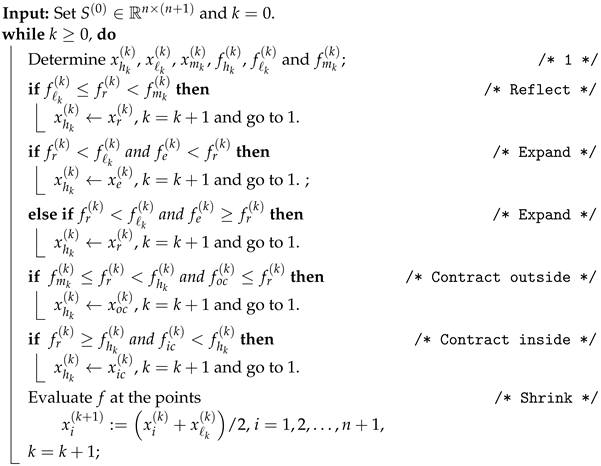

We first define the original Nelder–Mead simplex method in the following form (see [1,6,22]).

The simplex of iteration k is denoted by , where denotes vertex i of iteration k. The function values at the vertices are denoted by (). We define the index of the worst vertex (), the best vertex () and the second worst vertex () as follows:

Note that , and they are not necessarily unique. Define the center and straight line as follows:

The reflection, expansion, outside and inside contraction points of simplex are defined as

The corresponding function values are denoted by , , and , respectively.

The original Nelder–Mead simplex method is given by Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Original Nelder–Mead algorithm. |

|

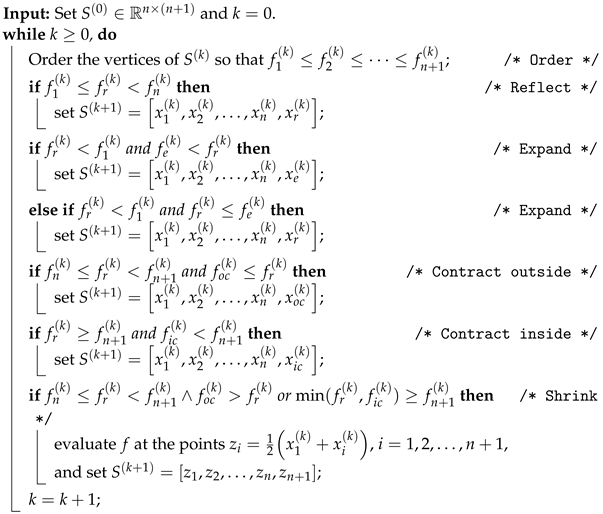

The “decision boundaries” are the same as in the ordered Nelder–Mead method of Lagarias et al. [12], which is given in Algorithm 2. Suppose that

holds for the initial simplex vertices and that this ordering is kept during the subsequent iterations. Here, , and for all k.

There are two rules of reindexing after each iteration. For a nonshrink step, is replaced by a new point . The following cases are possible: , and . Define

Then, the new simplex vertices are

This ‘insertion rule’ puts v into the ordering with the highest possible index, guaranteeing that () and

If shrinking occurs, then the new vertices must be ordered such that if ().

For a given and f, the sequence is uniquely defined by Algorithm 2. Clearly, this is not true for Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 2: Ordered Nelder–Mead algorithm. |

|

3. Matrix Representations for the Two Algorithms

The steps of both algorithms can be easily described by transformation matrices. We first consider Algorithm 1. If the incoming vertex () belongs to , then

where v replaces vertex . For , define the vector

with at the position j and the matrix

where is the j-th unit vector. Then, and

The shrinking iteration can be written as

where . It follows that

where

The set has exactly nonsingular matrices. Note that and .

For Algorithm 2, we have the following (see, e.g., [14,15]). Assume that simplex satisfies condition (4). Then, for nonshrinking iterations, the new simplex is given by

where

and

is a permutation matrix. If shrinking occurs, the new simplex is

where the permutation matrix is defined by the ordering condition (4) and is the set of all possible permutation matrices of order .

Define the sets

and

It follows that

where

The set consists of nonsingular matrices. For any , .

Observe that both algorithms are nonstationary iterations. Note that the number of shrinking matrices for Algorithm 2 increased to compared to the shrinking matrices of Algorithm 1.

4. Connections and Properties

Here, we investigate the connection between the transformation matrices of both algorithms, their consequences and the spectral properties of the matrices.

The corresponding transformation matrices of Algorithms 1 and 2 are connected by orthogonal similarities. For any ,

with and

with .

With and , denote the kth simplices of Algorithms 1 and 2, respectively. If a permutation matrix exists such that , and , then we can ask if and define the same simplex. The assumption implies that and . Hence, and

Since , and , we have

In the case of shrinking,

Note that . Hence,

Since , we have that

Hence, the simplices of iteration are the same for the ordering of vertices. Since the continuation of the original Nelder–Mead method is not uniquely determined, unlike in the case of Algorithm 2, we can expect similar although not identical results for both algorithms.

The following results are obvious. For any ,

Lemma 1.

The eigenvalues of are () and (). has the eigenvalues and () for . Both and have a diagonal Jordan form.

Corollary 1.

Sequences and are uniformly bounded for and convergent for (see, e.g., [23,24,25]).

Note that and , where

and

The first expression follows from a result on the singular values of companion matrices (see, e.g., Barnett [26] or Kittaneh [27]), while the second follows from a result of Montano, Salas and Soto [28].

Matrices , , , , () are left-stochastic. Hence,

We note that () is an involution. If is multiplied by a permutation matrix (), this property is lost. However, for , is a 6-involutory matrix, which is exploited in proving Theorem 3 (for k-involutory matrices, see Trench [29]).

The multiplication of or by a permutation matrix or P makes a significant change in the eigenstructure. The following results hold (see Theorem 3 and Corollary 1 of Galántai [15]).

Theorem 1.

- (i)

- has at least one eigenvalue .

- (ii)

- () has at least two eigenvalues .

- (iii)

- If and , then has exactly eigenvalues .

- (iv)

- For , has exactly one eigenvalue , while the remaining n eigenvalues are in the open unit disk.

- (v)

- If and , then has exactly eigenvalues , while eigenvalues are in the open unit disk.

- (vi)

- If and , then all the eigenvalues of are on the unit circle.

- (vii)

- If and , then has a second eigenvalue in the interval and all its eigenvalues are in the annulus .

Corollary 2.

The eigenvalues of () are and for .

5. Convergence of the Function Values at the Vertices

Lagarias et al. [12] studied the convergence of function values at the simplex vertices for Algorithm 2. We cite their two most important results, before proving more general results for both Algorithms.

Lemma 2

(Lemma 3.3 of [12]). If function f is bounded from below on and only a finite number of shrink iterations occur, then each sequence (generated by Algorithm 2) converges to some limit for and .

Lemma 2 guarantees the convergence under rather general conditions. In general, the limit values can be different as shown by Examples 1 and 2 of [20] (also see [15,21]).

Theorem 2

(Theorem 5.1 of [12]). Assume that f is a strictly convex function on with bounded level sets. Assume that is non-degenerate. Then, the Nelder–Mead simplex method (Algorithm 2) converges in the sense that .

Theorem 2 is generally considered as the main result of [12]. In addition, it can be proved (see [20]) that if f is strictly convex on with bounded level sets, is non-degenerate (affine invariant); thus, any accumulation point of the simplex sequence (generated by Algorithm 2) has the form .

We need the following concept and results.

Definition 1.

Let f be defined on a convex set . The function f is said to be quasiconvex on S if

for every and for every .

Convexity implies quasiconvexity.

Lemma 3

(Lemma 6 of [20]). If f is quasiconvex and bounded below on , then each sequence is monotone decreasing and converges to some limit for . Furthermore, .

Corollary 3

(Corollary 2 of [20]). If f is convex on and an index exists such that , then and no shrinking occurs in iteration k.

Lemma 4

(Lemma 10 of [20]). Assume that f is convex and bounded below on . If for some integer ℓ (),

then there is an index such that for all , , that is, the first ℓ vertices do not change.

Lemma 5

(Lemma 11 of [20]). If f is convex and bounded below on , then .

The following generalization of Theorem 2 of Lagarias et al. was proved in [20]. Here, we present it with a new short proof.

Theorem 3.

Assume that f is a convex function on and is bounded below. Then, the Nelder–Mead simplex method (Algorithm 2) converges in the sense that .

Proof.

It follows (Lemmas 3 and 5) that . Assume that . It follows from Lemma 4 that there exists an index such that for , . Hence, only and may change. The insertion rule and the impossibility of shrinking (Corollary 3) imply that only the following cases are possible:

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- and ;

- (iii)

- and .

We assume that is big enough, so that for , , (), where is such that . Depending on the selected case, , or must hold. In case (i), replaces and . In case (ii), since , we have

Hence, case (ii) cannot occur. Similarly, in case (iii),

showing that case (iii) cannot occur. Hence, we can only have the simplex sequence

Since is a 6-involutory matrix (), is a periodic sequence and , which is impossible by the insertion rule. This is a contradiction; thus, . □

For Algorithm 1, we prove the following results. First, observe the following facts. For nonshrink steps, we have

- (i)

- for , ;

- (ii)

- () and ;

- (iii)

- ;

- (iv)

- and .

Hence, ().

Lemma 6

(Algorithm 1). If is bounded below and only a finite number of shrink operations occur, then there exist finite limit values such that ().

The only difference to Lemma 2 is that the function values and their limits are not ordered.

Lemma 7

(Algorithm 1). If is quasiconvex on and bounded below, then there exist finite limit values such that ().

Proof.

If f is quasiconvex, then in the case of shrinking, the inequality

also holds. So does Lemma 6. □

Lemma 8

(Algorithm 1). If is strictly convex, then no shrinking occurs.

Proof.

Shrinking happens if or holds. In general, . If , then . If , then . □

Remark 1

(Algorithm 1). Assume that is convex. Then, . If , then . If , then . However, if at least for one , holds, then and . In such a case, there is no shrinking.

Assume that is bounded below and only a finite number of shrink operations occur. Then, we have finite numbers such that as , and each is monotone decreasing (). The values are unordered. However, there is permutation of the indices such that

Lemma 9

(Algorithm 1). If f is convex and bounded below on , then .

Proof.

Assume that . Lemma 6 and Remark 1 imply that for , there exists an index such that for ,

Note that (). Hence, there cannot be shrinking, and only the worst vertex can change for (). Clearly, for . If , then by definition. Hence, only the cases are possible. For simplicity, let . Then,

and

Since (), it follows that

and

Since f is convex, we have

which is a contradiction. Hence, holds under convexity. □

Theorem 4.

If f is convex and bounded below on , then Algorithm 1 converges in the sense that .

Proof.

Lemmas 6 and 9 imply that for some permutation of . Assume that . Then, there exists an index K such that for , () holds with . Since , only vertices and can change for . Also, note that implies that no shrinking may occur. It also follows that only are possible. Consider now the following ’possible’ cases:

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- and ;

- (iii)

- and .

In the first case, and . Hence, the operation must be followed by () for some . In the second case,

which makes this particular step impossible. Similarly, in the third case,

this step is impossible. Hence, the only possible step is with and . In fact, we have for a pair of and , and this is repeated. Consider the following possible cases:

It is easy to check that for every ,

Here, we have a periodicity, , which is impossible by the condition . Hence, must hold. □

Theorems 3 and 4 are generalizations of Theorem 2 of Lagarias et al. [12], since they require only convexity and boundedness from below. Moreover, their proofs are much simpler.

6. Convergence of the Simplex Sequences

Here, we study the convergence of the simplex sequence generated by both Nelder–Mead methods. If , then (provided that f is continuous) for as . The limit vertices can be different (see, e.g., Examples 1 and 2 of [20]).

Ideally, should converge to some limit of the form , where is a stationary point of . MacKinnon’s example [19] and Example 3 of [15] show that is not always a stationary point.

If converges to a rank one matrix of the form (), then and diameter . There are several examples (see, e.g., [14,15,20,21]), where the simplex sequence converges to a limit with diameter and rank (, rank .

The following necessary and sufficient result holds for both algorithms.

Lemma 10.

Assume that is non-degenerate (affinely independent). Then, (generated by Algorithm 1 or 2) converges to some if and only if converges to some .

Proof.

In both cases , where (in case of Algorithm 1) or (in case of Algorithm 2). If , then . Since , we have

By assumption, the first matrix on the right is invertible and so

If , then

□

From now on, we assume that is always non-degenerate (its columns are affinely independent). Lemma 10 is formally independent of f. However, the decision mechanism of the NM algorithm determines the next simplex and the resulting matrix product. Certain configurations clearly cannot occur. Such is the case of strictly convex functions, when no shrinking can occur or cannot be repeated in a sequence more than five times (for the case ). In general, it is hard to tell what sequences (products) are possible for a given f.

Lemma 11.

If (, or ), then rank .

Proof.

Assume that rank . Then, is invertible. Since all of is invertible, . As ,

Hence, is necessary for an invertible . Since or is a finite set and its elements are different from I, this cannot happen and rank . □

Sylvester’s theorem on rank (see, e.g., Mirsky [30]) implies that

Since, by assumption, rank , we have rank rank . In Example 4 of [15], rank , rank and rank .

The following simple result characterizes the possible limits of infinite matrix products.

Lemma 12.

Assume that () and occurs infinitely often in the product , then every nonzero row of is a left eigenvector of belonging to the eigenvalue .

Proof.

Since appears infinitely many times in the product , there is a subsequence of with rightmost factor , say

where the s are products of s. Since , we have . □

Define the (left) 1-eigenspace of matrix A by . The rows of belong to . If several , say (), occur infinitely often in the product , then the rows of belong to .

Since for all and for all , we have and , respectively. If or , then has the form for some .

Note that for any or , . Hence, if , then , that is, . If , then implies that .

We recall the following definitions and results (see, e.g., Hartfiel [31,32]).

A right infinite matrix product is an expression . A set of matrices has the right convergence property (RCP), if all possible right infinite products () converge.

A set of matrices is product-bounded if there is a constant such that for all k and all .

If is an RCP set, then is also product-bounded.

Lemma 13.

If is an RCP set, and λ is an eigenvalue of , then or , and this eigenvalue is simple. Hence, each matrix of must satisfy this condition.

The matrices and have at least one eigenvalue greater than 1, and and in any induced matrix norm. Hence, and are unbounded. There are also examples when the Nelder–Mead algorithm produces unbounded simplex sequences or (see, e.g., [14,15,20]). It is clear that the whole matrix set or is not an RCP set.

Hence, we must seek for subsets of or , which are RCPs. However, Blondel and Tsitsiklis [33] proved that the product boundedness of a finite matrix set is algorithmically undecidable and it remains undecidable even in the special case, when consists of only two matrices. Since product boundedness is a weaker property than the RCP from which it follows, and although it is algorithmically undecidable, it seems difficult to decide the RCP property in general. This might answer question (e) of Wright.

However, it is relatively easy to identify one particular RCP set. For both algorithms, the corresponding shrinking matrices form an RCP set.

Lemma 14.

Both and are RCP sets.

Proof.

By using induction on k, we can prove that for ,

and

For the last formula, note that if P is a permutation matrix, then and for some j. In element-wise partial ordering, holds for and

Here, as , and the sequence is monotone increasing in component-wise partial ordering. Hence, is convergent. We also have that , as , and is monotone increasing in partial ordering. Hence, is convergent. □

Remark 2.

Corollary 2 implies that for all . If matrices () occur infinitely often in the product and (), then the nonzero rows of belong to . Hence, for some w. Lemma 1 implies that for all . It also follows from the previous argument that for some w.

The for the infinitely repeated shrinking process also follows from Cantor’s intersection theorem.

Lemma 15.

Define the matrix

Then, for all ( or ), the matrix has the common block lower triangular form

where and .

The result was proved for in [14,15]. The proof of case is similar. Since both and are finite sets, there exist two constants such that and for all or . For , the corresponding has eigenvalues of and . For (), . However, for with and , the corresponding s have all their eigenvalues in the open unit disk (see Theorem 1). Hence, they can be elements of an RCP set.

If

then

If the infinite matrix product ( () or ()) converges to a rank-one matrix of the form , that is, if (, ), then it follows that

Lemma 16.

For the convergence of the simplex sequence to a common point, it is necessary and sufficient that both

and

hold for some vector .

It is clear that the infinite products of or satisfy these conditions. We recall the following simple result.

Lemma 17

([14,15,16]). Assume that , is convergent () and that for all k. Then, converges and

for some .

If for all i, then the speed of convergence is linear (geometric). This follows from and the inequality

with .

We recall the following result (see Hartfiel [31], Corollary 6.4, Daubechies and Lagarias [34]).

Lemma 18.

Let be a compact matrix set. Then, every infinite product, taken from , converges to 0 if there is a norm such that , , for all .

Hence, there must be a norm such that , for all (or ). Note that Lemma 18 is not constructive. However, for the convergence of (for all ), the condition () is necessary and sufficient.

For Algorithm 1, is the only subset that satisfies this requirement. For Algorithm 2, define the set and assume that

- (A)

- there exists a matrix norm (induced by a vector norm ) such that if , then .

If (A) holds, then is an RCP set and every infinite product () has the form for some w. It follows from Theorem 1 that for , .

The existence of such norm of the form was proved in [14] for and in [15] for . For the cases , the corresponding matrices S, found experimentally by direct search methods, are given in Appendix A. Since the eigenvalues of (, ) that lay inside the unit disk converge to 1 for (see Lemma 3 of [15]), it is hard to find a norm with property (A) for greater n values.

The obtained RCP sets and are quite narrow. However, we can keep the convergence of any infinite product from or by inserting an infinite number of matrices from under proper conditions (for Algorithm 2, see [14,15]). For Algorithm 2, it was also observed [16] that several fixed-length matrix products have spectral norms less than 1. Upon these observations, the convergence set of both algorithms can be significantly expanded.

Assume again that or . Moreover, introduce the notation

and consider the product , where

Let

Then,

and

where and are uniformly bounded.

Assume that and consider the expression

which is clearly equal to (32).

For , define the sets

For any , we have the estimates and . Hence, by Lemma 17, the set is an RCP set, and the limits of the infinite products are of the form .

Now, consider the product

where (), () and are fixed (). The corresponding reduced form is

Consider the product (), where the number of factors that belong to is . Clearly, . There exists a such that . Assume that there is a number such that . Then,

Since and the conditions of Lemma 17 hold, we proved the following result.

Theorem 5.

Assume that , is non-degenerate, is fixed and is not empty. Let be the number of ℓ products that belong to during the first k iterations of the Nelder–Mead method (Algorithm 2). Moreover, assume that for an integer , and for some , . Then, the Nelder–Mead method (Algorithm 2) converges in the sense that

with a convergence speed proportional to .

Note that assumption , which is a density condition, yields an infinite number of factors from the set as . The larger the ratio , the wider the convergence set. Theorem 5 is clearly true for any pair of subsets and such that and .

For Algorithm 1 and some , , to which we cannot add more elements, since in any induced matrix norm. For Algorithm 2, under Assumption (A).

Theorem 5 was first proved for Algorithm 2 for in [14,15] and for in [16] in a slightly different way and form. The conditions were verified for a spectral norm and up to dimension .

The computational results of Section 7 show that for , and (see also [16]). Hence, Theorem 5 indeed extends the convergence sets and (quite significantly).

Upon the basis of the earlier version of Theorem 5, a stochastic convergence result was proved for Algorithm 2 in [16]. Since Theorem 5 holds for both algorithms, this can be extended for Algorithm 1 as well. However, it will be published later for reasons discussed in Section 7.

7. Computational Results and Conclusions

Here, we consider the cardinality of set for both algorithms with and without shrinking operations.

Define the quantities and . The larger the ratio or , the wider the convergence set. Table 1 and Table 2 contain the computed values or , respectively.

Table 1.

Ratios for Algorithm 1.

Table 2.

Ratios for Algorithm 2.

Note that and . The ratio cannot achieve 1 (see the examples within Section 1 and Section 6). For increasing n, the shrinking matrices somehow distort the real situation, since it is unlikely that all possible shrinking steps occur for one particular function.

It is clear that Algorithm 2 has a wider convergence set than Algorithm 1.

If we discard the shrinking operations (the case of strictly convex functions), then Theorem 5 also holds for the pair of sets

and

instead of and , respectively. Define again the ratios and . Note that for and some , . Table 3 and Table 4 contain the computed values of and , respectively.

Table 3.

Ratios for Algorithm 1 without shrinking.

Table 4.

Ratios for Algorithm 2 without shrinking.

The comparison of the last two tables shows again that Algorithm 1 has a smaller convergence set and a slower convergence rate than Algorithm 2.

We can observe that the larger the ℓ, the larger is the ratio in all four tables. Although the ratios cannot achieve 1, it is conjectured that they might be quite close to 1 for a large ℓ.

For both algorithms, we can observe the increase in convergence sets, if ℓ is increasing. For larger n values, this increase is slower, especially if no shrinking is allowed. However, this requires an enormous computational time to check, even for modest pairs of n and ℓ. The reason for this behavior is unknown and yet to be investigated. However, we can establish the following conclusions. In case of the convergence of the simplex sequence, Algorithm 2 is better than Algorithm 1. Hence, the ordering of Lagarias et al. [12] significantly improved the classical Nelder–Mead simplex method.

Theorem 5 indicates that the generated simplex sequence has a strong tendency to converge to one common limit point. This, together with Lemma 2 (or Lemma 3), may guarantee that the Nelder–Mead simplex algorithm generates good practical results.

In the case of the convergence of function values at vertices, the novel results are essentially the same for both methods. The extension of Theorems 2, 3 or 4 for is an open question. For , all proofs exploit (implicitly or explicitly) an involuntory property, which does not hold for . How the convexity assumptions can be relaxed further is also an open question. If f is quasiconvex on and bounded from below, then . However, the other parts of the proof do not work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The author is indebted to J. Abaffy and L. Szeidl for their help and comments. He is also indebted to the unknown referees whose observations and suggestions helped to improve this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

The matrices for the norm and .

The case where :

The case where :

References

- Nelder, J.A.; Mead, R. A simplex method for function minimization. Comput. J. 1965, 7, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spendley, W.; Hext, G.; Himsworth, F. Sequential application of simplex designs in optimisation and evolutionary operation. Technometrics 1962, 4, 441–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audet, C.; Hare, W. Derivative-free and Blackbox Optimization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, A.; Scheinberg, K.; Vicente, L. Introduction to Derivative-Free Optimizations; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, C. Iterative Methods for Optimization; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochenderfer, M.; Wheeler, T. Algorithms for Optimization; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, F.; Morgan, S.; Parker, L.; Deming, S. Sequential Simplex Optimization; CRC Press LLC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, J.; Menickelly, M.; Wild, S. Derivative-free optimization methods. Acta Numer. 2019, 28, 287–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rykov, A. System Analysis. Models and Methods of Decision Making and Search Engine Optimization (in Russian); MISiS: Moscow, Russia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Heeman, P. On Derivative-Free Optimisation Methods. Master’s Thesis, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rios, L.; Sahinidis, N. Derivative-free optimization: A review of algorithms and comparison of software implementations. J. Glob. Optim. 2013, 56, 1247–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarias, J.; Reeds, J.; Wright, M.; Wright, P. Convergence properties of the Nelder-Mead simplex method in low dimensions. SIAM J. Optimiz. 1998, 9, 112–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, C. Detection and remediation of stagnation in the Nelder-Mead algorithm using an sufficient decrease condition. SIAM J. Optimiz. 1999, 10, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galántai, A. Convergence theorems for the Nelder-Mead method. J. Comput. Appl. Mech. 2020, 15, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galántai, A. Convergence of the Nelder-Mead method. Numer. Algorithms 2022, 90, 1043–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galántai, A. A stochastic convergence result for the Nelder-Mead simplex method. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M. Direct search methods: Once scorned, now respectable. In Numerical Analysis 1995 (Proceedings of the 1995 Dundee Biennial Conference in Numerical Analysis); Griffiths, D., Watson, G., Eds.; Addison-Wesley Longman: Harlow, UK, 1996; pp. 191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, M. Nelder, Mead, and the other simplex method. In Documenta Mathematica, Extra Volume: Optimization Stories; FIZ Karlsruhe GmbH: Eggenstein-Leopoldshafen, Germany, 2012; pp. 271–276. [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon, K. Convergence of the Nelder-Mead simplex method to a nonstationary point. SIAM J. Optimiz. 1998, 9, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galántai, A. Convergence of the Nelder-Mead method for convex functions. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2024, 21, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galántai, A. A convergence analysis of the Nelder-Mead simplex method. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2021, 18, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, E. ; G.-Tóth, B. Introduction to Nonlinear and Global Optimization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburger, R. Infinite powers of matrices and characteristic roots. Duke Math. J. 1940, 6, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C. Matrix Analysis and Applied Linear Algebra; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, R.; Johnson, C. Matrix Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, S. Matrices: Methods and Applications; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kittaneh, F. Singular values of companion matrices and bounds of zeros of polynomials. SIAM J. Matrix. Anal. Appl. 1995, 16, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, E.; Salas, M.; Soto, R. Positive matrices with prescribed singular values. Proyecciones 2008, 27, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trench, W. Characterization and properties of matrices with k-involutory symmetries. Linear Algebra Its Appl. 2008, 429, 2278–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsky, L. An Introduction to Linear Algebra; Dover Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hartfiel, D. Nonhomogeneous Matrix Products; World Scientific: Singapore, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyn, W.J.; Elsner, L. Infinite products and paracontracting matrices. Electron. J. Linear Al. 1997, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondel, V.; Tsitsiklis, J. The boundedness of all products of a pair of matrices is undecidable. Syst. Control Lett. 2000, 41, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubechies, I.; Lagarias, J. Sets of Matrices All Infinite Products of Which Converge. Linear Algebra Its Appl. 1992, 161, 227–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).