Abstract

Cryptographic S-boxes are vectorial Boolean functions that must fulfill strict criteria to provide security for cryptographic algorithms. There are several existing methods for generating strong cryptographic S-boxes, including stochastic search algorithms. These search algorithms typically generate random candidate Boolean functions (or permutations) that are improved during the search by examining the search space in a specific way. Here, we introduce a new type of stochastic algorithm for generating cryptographic S-boxes. We do not generate and then improve the Boolean function; instead, we build the vector of values incrementally. New values are obtained by randomized search driven by restrictions on the differential spectrum of the generated S-box. In this article, we formulate two new algorithms based on this new approach and study the better one in greater detail. We prove the correctness of the proposed algorithm and evaluate its complexity. The final part contains an experimental evaluation of the method. We show that the algorithm generates S-boxes with better properties than a random search. We believe that our approach can be extended in the future by adopting more advanced stochastic search methods.

1. Introduction

A substitution box (S-box) is a principal component of a large class of symmetric ciphers. The main task of the S-box is to provide nonlinearity to the cipher design, creating a property called confusion [1]. From the mathematical point of view, a cryptographic S-box is a vectorial Boolean function , which fulfills specific criteria. We refer the reader to [2] for a more thorough study of Boolean functions used in cryptography.

We can evaluate a vectorial Boolean function with respect to some S-box criteria and assign a quality to an S-box (with respect to these criteria). An S-box that fulfills prescribed criteria is called a strong S-box, while an S-box that lacks in some criterion is called a weak S-box. The S-box criteria include:

- Nonlinearity, which measures the resistance against the linear cryptanalysis [3]. Nonlinearity is computed as a minimum distance to all affine functions, which can be efficiently implemented with a Fast Walsh–Hadamard transform. Cryptographic applications require S-boxes with nonlinearity that is as high as possible.

- Differential profile, which measures the resistance against the differential cryptanalysis [4]. The differential profile measures the probability of the difference propagation, and should be as flat as possible. In this article, we focus exclusively on the differential profile. We provide more details in the following text.

- Balancedness [5], which is required to achieve uniform distribution of output bits. A balanced Boolean function has the same number of zeroes and ones in its vector of values. Note that it is easy to show that Boolean permutation (bijective vectorial Boolean function) is always balanced.

- Strict Avalanche (SAC) and Output Bit Independence (BIC) [6,7], which measure the diffusion properties of the S-box.

- Algebraic immunity [8], which measures the resistance against algebraic attacks on symmetric ciphers.

- Multiplicative complexity [9], which measures the complexity of the S-box implementation in terms of the number of AND gates required to implement the S-box. High multiplicative complexity means that S-box implementation in hardware is more costly. On the other hand, S-boxes with low multiplicative complexity can be weak with respect to other criteria.

- Other criteria, such as differential profile with respect to addition modulo [10]. This can cover special cases required by non-standard cipher designs.

An important task in cipher design is to generate strong S-boxes, as using a weak S-box can weaken the cipher. Even if the overall cipher design fixes the weakness introduced by a weak S-box, it would be less efficient than the design which uses strong S-boxes. There are multiple methods for generating strong S-boxes, which we review in Section 2. While efficient algebraic constructions of S-boxes with good cryptographic properties are known, we prefer to generate S-boxes with stochastic methods that can choose S-boxes from a large set of possible candidates and are not restricted to specific algebraic classes. Our main reason is that some cipher designs can be vulnerable against algebraic attacks (see, e.g., [11]), and these types of attacks can be specific to only certain classes of S-boxes.

Thus, our goal is to generate S-boxes with better properties than can be obtained from a randomly generated vectorial Boolean function while keeping the S-box space as large (and diverse) as possible. For this purpose, we have introduced a new algorithm for generating S-boxes with prescribed differential properties. Unlike other known stochastic methods, our algorithms build the S-box in incremental steps. After each new value, we check the partial differential table. If the partial S-box does not fulfill the criteria, we use backtracking to explore a different branch of the search space. The algorithm is formally presented in Section 3.

Note that in our search algorithm we focus on a single S-box criterion, the maximum value of the so-called Difference Distribution Table (DDT). We define the Difference Distribution Table (sometimes called the XOR table) of S-box S as a matrix over , with dimension . When S is known from the context, we simply write . Rows of are indexed by vectors , while columns are indexed by vectors . An element at position has a value

The differential profile of an S-box S is a multiset of values from for . S-box S is differentially -uniform if , that is, is the maximum value in the whole DDT excluding the case . Our goal is to construct S-boxes with low differential uniformity, which are important in constructing ciphers resistant to differential cryptanalysis.

It might be possible to generalize our algorithm for multiple criteria; however, we wanted to keep this research focused. We suspect that it would be too difficult to understand and analyze the method properly if we wanted to include multiple criteria. By investigating a single criterion, we can evaluate the complexity of the algorithm analytically (Section 4). We provide experimental results for small S-boxes in Section 5. Finally, we discuss our results and open research questions in Section 6.

2. Methods for Generating Cryptographic S-Boxes

There are a large number of different methods for generating cryptographic S-boxes. In this section, we provide a brief non-exhaustive overview of existing methods. The S-box generation methods can be categorized into the following main categories:

- (Pseudo-)random generation

- Stochastic search

- Mathematical construction

- Construction from smaller components.

2.1. Random S-Boxes

The easiest way to generate an S-box is to choose a candidate randomly. It is obvious that such a randomly generated S-box will not have the strongest cryptographic properties. On the other hand, a randomly generated Boolean function will not be too weak, either. Pseudo-random S-box generation is based on a known pseudo-random generator initialized with a known seed. If the seed is not controlled by the cipher designers, the randomness of the S-box generation can be verifiable by third parties.

A (pseudo-)random S-box generation can be improved by examining a larger set of S-boxes and taking either the best candidate or the first candidate that fulfills the required design restrictions. An example is the basis of the algorithm used to generate S-boxes for the AES candidate MARS [12]. The authors tested roughly candidates on five differential and four linear criteria. Note that this algorithm combines random generation with an extra “early abort”, that is, when a special criterion (with a low probability of occurrence) is encountered, a candidate is modified in such a way that the criterion is satisfied.

2.2. Stochastic Search

Random S-box generation is a complex computational problem, as it takes a very long time to enumerate and examine all possible candidates until a suitable candidate with the required properties is found. With increasing size of the S-boxes, the space of potential candidates grows super-exponentially. For a fixed S-box size, strengthening the criteria increases the search time exponentially. One of the methods for decreasing the search time and increasing the quality of S-box candidates is to apply various stochastic search heuristics from the areas of artificial intelligence and evolutionary computation.

Artificial intelligence and evolutionary computation play an important in both cryptanalysis [13] and cipher design [14]. The seminal works in this area include the use of Simulated Annealing [15], Hill-Climbing [16,17], and their combinations and extensions [17] for generating cryptographic S-boxes.

Modern stochastic search methods provide very strong experimental results, especially when considering multi-objective optimization [18]. In [19], the authors presented an optimization of the simulated annealing (SA) algorithm. In [20], a parallel application of tabu search and simulated annealing was employed. A method based on a memorable simulated annealing algorithm was successfully applied in [21] to generate chaotic S-boxes. A reversed genetic algorithm for generating S-boxes was proposed in [22]. The search starts from a mathematically constructed set of candidates (see the next section) and improves the diversity and quality of candidates by stochastic search based on genetic algorithms. Genetic algorithms can be used to find cellular automata-based S-boxes [23,24]. Stochastic search methods can be improved in terms of both the quality of results and the complexity of algorithms by investigating new implementation techniques and cost functions [25].

Our proposed algorithm is based on an exhaustive search with early rejection. We believe that it might be possible to improve the proposed method by adopting a combination of the proposed search method and evolutionary search methods. Inspiration can be found in [26], for instance, where a combination of a special genetic algorithm and total tree searching produced S-boxes with high nonlinearity.

2.3. Mathematical Construction

A different approach to the construction of S-boxes is to use mathematical (or algebraic) construction of S-boxes. Mathematically constructed S-boxes are based on using a family of Boolean functions with known security properties [2], such as the Gold functions [27], the Kasami functions [28], the Bracken–Leander functions [29], Dillon’s permutation [30], and others. New functions with good properties can be derived mathematically from these known constructions [31].

One of the most commonly used families of functions is based on inverse mapping. As an example, the function in is known to be four-differentially uniform [32] and to have high nonlinearity and algebraic degree. The S-box of the current Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) was constructed by applying an affine transformation to this function. Another way of mathematical constructing S-boxes is using cubic polynomial mapping [33].

In [34,35,36,37], the authors applied various optimizations to AES S-box generation. A key-dependent mechanism to generate S-boxes with good cryptographic properties was used in [38,39]. A similar approach combined with other proposed optimizations was applied by the authors of [40,41,42,43].

A different approach was used in [44,45]. The authors replaced the binary representation of S-boxes with a domain quasigroup G, making it possible to find functions that are at the same time both balanced and perfectly nonlinear. Such functions have a completely flat difference distribution table.

2.4. Construction from Smaller Components

A Boolean function can be implemented in (AND, XOR) algebra (or any other Boolean algebra). The minimum number of AND-gates in the (AND, XOR) representation of a Boolean function is called the multiplicative complexity (MC). The MC is an important property for various problems connected to S-boxes, such as logic circuit minimization, algebraic cryptanalysis, and optimal masking against higher-order power analysis attacks. However, low multiplicative complexity can conflict with other S-box criteria, such as nonlinearity and differential uniformity.

In [9], we provided an analysis of multiplicative complexity for all bijective S-boxes and showed that MC of any S-box is at most 5. It is, however, difficult to determine the MC of an existing (larger) S-box. Thus, in [46], we described the process of generic construction, which can be applied in the construction of strong S-boxes with low multiplicative complexity. Instead of analyzing an existing complex Boolean function, we constructed an S-box from smaller primitives with known multiplicative complexity.

3. New Algorithm for Generating S-Boxes with Prescribed Differential Properties

The goal of an S-box generation algorithm is to produce an S-box, which is a vectorial Boolean function

that fulfills specific criteria. For a given there are possible functions S. In general, for each potential S, we define some evaluation function that returns a score with respect to selected criteria. If the score is below some limit, we reject the Boolean function (a weak S-box); otherwise, we produce S as a result of the S-box generation. We aim to obtain an S-box with as high a score as possible, but are limited by computational resources, as even for small it might be impossible to examine the whole search space.

Our new algorithm is based on a randomized search with early rejection. Our search criteria are reduced to a single dimension; we evaluate the Difference Distribution Table (DDT) of the S-box and reject all S-boxes with DDTs containing values above some pre-selected threshold . Threshold should be selected according to the security requirements. Our algorithm either produces a -uniform S-box or proves that no such S-box exists. Note that if we set the threshold too low, the algorithm might take too long to find a suitable S-box or exhaust the search space. The complexity analysis provided in Section 4 can help to select a suitable threshold that balances security requirements and the running time of the algorithm.

The main advantage of our algorithm in comparison with a simple search is that we can evaluate the DDT based on a piece of partial information about the function S. This allows us to reduce the search tree size by cutting whole unproductive branches, essentially performing an early rejection sampling in the search space. Thus, it can produce good S-boxes with less work than a simple exhaustive or random search.

3.1. Partial DDT

Let be a vectorial Boolean function. We say that S is partially determined on P if we have a set of points with , , and for each . The Partial Difference Distribution Table of partially determined S is a matrix with elements

We can compute the partial DDT of an S-box given lists with Algorithm 1. We suppose that lists encode pairs in a given order of elements. Note that if lists are extended by one element, the next PDDT can be computed efficiently by simply adding extra values to the previous PDDT by computing differences of the last added pair with previous pairs in the partial S-box.

| Algorithm 1 Partial DDT construction algorithm. | |

| Require: | {Lists defining a partial S-box of the same length l.} |

| Require: | {S-box dimensions.} |

| for all do | |

| for all do | |

| end for | |

| end for | |

| return | |

Because , each . Thus, given a partially evaluated S, we can check whether satisfies our pre-selected threshold . If for some , , then as well. Thus, we can quickly reject partial S without evaluating other points from \X and use backtracking to check for other more suitable branches of the search tree.

Note that we can place other stricter criteria on DDT. However, we require that these criteria are preserved when using partial DDT, e.g., we can have more strict restrictions on specific rows or columns of the DDT. This can be useful for cipher designs based on simple substitution permutation networks, e.g., a present-like cipher [47] with a custom S-box, which requires stronger criteria on rows and columns of the DDT indexed by indices with low Hamming weight. In general, we can define a function with the input being a partial DDT, which returns true if the partial DDT satisfies S-box criteria and false otherwise. In our analyses, we use a simple function that only checks whether for each .

3.2. General Idea of the Algorithm

The general idea of our randomized search algorithm is presented as Algorithm 2. We store a partially determined S-box using lists . In each step, we choose a random new point a from the remaining unassigned points from and determine a random coordinate . Then, we check the partial DDT; if it satisfies the conditions, we extend lists and continue with the algorithm. When we have assigned a value to each point from , we return a finished S-box with a DDT that satisfies the criteria.

In general, Algorithm 2 is not guaranteed to find an S-box; a partial S-box given by sets may be constructed with a correct partial DDT in such a way that no successor fulfills the DTT criteria. Thus, we need to introduce an additional parameter, limit, that can be used to restrict the search to a fixed number of maximum retries.

| Algorithm 2 Randomized algorithm to construct S-boxes with prescribed differential table. | |

| Require: , S-box input size. | |

| Require: , S-box output size. | |

| Require: , a function that returns true if partial DDT satisfies criteria. | |

| Require: , the maximum number of tries. | |

| while do | |

| if then | |

| return ∅ | |

| end if | |

| {for bijective S-box use: } | |

| if then | |

| end if | |

| end while | |

| return | |

Note that the presented methods can be used to generate both general S-boxes (any vectorial Boolean function) and bijective S-boxes,. When generating bijective S-boxes, it is necessary to set the same S-box input and output size () and restrict the selection of the y values to ensure that no y value is repeated. The appropriate modification is marked in the formal descriptions of Algorithms 2 and 3 in the comments.

3.3. Main Algorithm

The disadvantages of Algorithm 2 lead us to a final version of the search algorithm that is based on a depth-first search with backtracking. This algorithm is formalized as Algorithm 3.

In Algorithm 3, we initialize arrays with potential elements from in random order. Then, we try to fill in the partial S-box in a fixed order of x, with stored in the growing list Y. For each new x, we take the next element y from (representing ) and check whether the conditions on partial DDT of the potential S-box hold. If PDDT is correct, we continue with new x; otherwise, we remove y from , and try the next one.

If all y on a level have been removed, it is neceesary to backtrack. We remove the last stored assignment of by decreasing active x and removing y from Y and the corresponding set. After backtracking, we continue to investigate the remaining options in , or backtrack again if all options are exhausted.

In practice, it is possible to speed up the search by exploiting the affine equivalence of S-boxes; see, e.g., [9]). This means that when or for some , we only use . In this case, the algorithm generates a normalized representative of an affine class of S-boxes with the required DDT. This method cannot be applied when looking for additional properties of the DDT, such as special distribution of values in rows and columns of the DDT.

| Algorithm 3 Depth-first search algorithm to find S-boxes with prescribed differential table. | |

| Require: , S-box input size. | |

| Require: , S-box output size. | |

| Require: , a function that returns true if partial DDT satisfies criteria. | |

| for all do | |

| {Store elements in random order.} | |

| end for | |

| x ← 0 | |

| while do | |

| {If bijective S-boxes are required, use instead.} | |

| for all do | |

| if then | |

| {Increse depth.} | |

| else | |

| {Dead end, try other branches.} | |

| end if | |

| end for | |

| {Search failed?} | |

| if and then | |

| return ∅ | |

| end if | |

| {Backtracking needed?} | |

| if then | |

| {Reset options on this level.} | |

| {Decrease search level.} | |

| {Remove last element of Y.} | |

| {Explored, no suitable successors.} | |

| end if | |

| end while | |

| return | {Whole S-box is determined.} |

Algorithm 3 is a typical example of an exhaustive search algorithm. Thus, it always stops and produces the required results if any S-box that satisfies the conditions exists. However, in the worst-case scenario the algorithm needs to examine the whole search space, with potential complexity as high as DDT evaluations. However, because unproductive branches are cut off, the proposed algorithm terminates sooner than a simple exhaustive search that only checks the DDT of the whole S-box. A more detailed complexity analysis is provided in Section 4.

3.4. Example Run of the Algorithm

In Table 1, we provide a small example run of Algorithm 3. We use parameters and try to restrict DDT in such a way that each . Additionally, we use affine equivalence and search only for bijective S-boxes to further restrict the search space for the sake of demonstration. Note that these choices only influence the selection of sets in Algorithm 3.

Table 1.

Example of S-box construction with (modified) Algorithm 3.

4. Complexity Analysis

Recalling our basic notation, we want to generate a suitable vectorial Boolean function variables with a differential spectrum bounded by . Thus, the difference distribution table of F should contain values d upper-bounded by .

To estimate the complexity, we abstract our algorithm using a “balls into bins” problem. We start with an matrix of empty bins. These correspond to possible DDT positions; thus, .

During the algorithm, we fill in the vector of function values of F of length N. After k steps of the algorithm, k positions out of N are filled. These fixed values determine existing differences in the partial DDT, distributed in at most rows.

In step , we add a new assignment . The k differences for address at most k rows of the DDT. For each i, we increase the DDT value in column . Due to using the ⊕ operation, all of the differences are paired; thus, we do not need to check the differences of , only to increase the DDT value directly by 2.

We abstract this in the “balls into bins” problem as follows. Each difference pair is a “ball” we throw into DDT “bins”; in iteration k, we independently and randomly choose k rows of bins, then throw a ball into bins in each of the chosen rows. The random variable represents the number of balls in a bin in row i and column j after the k-th iteration. In our algorithm the choices of DDT positions are not independent; however, we use as an estimate of the probability distribution of the generated partial DDTs after k steps of the algorithm (up to a scaling factor of 2).

4.1. Random Generation of S-Boxes

If there is no restriction on DDT, we can estimate the probability distribution of the final DDTs by computing . Alternatively, this should correspond to a simpler experiment in which we simply throw balls into bins. The generated function F is expected to be -differentially uniform with a probability of event

Distribution of balls in bins follows a multinomial distribution, with exclusive events (bins), equal event probabilities , and the number of trials equal to . Thus, the expected average number of balls per bin is . The most important case for S-box generation is when , which provides us with an expected average number of balls per bin near 1/2. Considering such samples, we now ask what the is probability that all samples are at most at the threshold in order to obtain a -differentially uniform S-box.

To simplify this calculation, we can replace individual binomial distributions with their Poisson approximation

which has . The probability that the sample size reaches the threshold is

The terms in the expansion converge rapidly to 0; thus, we can take the first term as the expected probability of a single bin containing at least t balls. The probability that none of the bins contains t or more balls is then estimated by

The estimated probabilities for and are summarized numerically in Table 2.

Table 2.

Estimated probabilities of random -differentially uniform S-boxes using “bins and balls” method.

Using the approximation

and Stirling’s approximation [48], we obtain

This means that when we decrease for a fixed n, our probability of generating a -uniform S-box decreases exponentially. Thus, we need to examine exponentially more randomly generated S-boxes to obtain one of suitable quality.

4.2. Analysis of the Algorithm 3

From the complexity point of view, Algorithm 3 has the advantage of early rejection compared to the general rejection sampling employed by a randomized depth-first search for S-boxes. A classical approach is to generate the whole S-box, compute DDT, and then reject or accept based on the threshold . Our new algorithm enables partial DDT sampling. If the partial sample contains DDT values above the threshold , further iterations of the algorithm cannot improve this value, meaning that it can be immediately rejected. Moreover, using a randomized depth-first search, we can exclude the whole set of samples that are above the threshold from the search.

Similarly to Section 4.1, we can estimate the probability of distribution of PDDT cells after s steps of the algorithm as follows:

where is an expected average value of “balls per bin” after s steps of the algorithm. The number of bins, value , does not change throughout the algorithm, however, the expected average occupancy of the bins grows with s.

If we carry out rejection sampling after exactly s steps of the algorithm, we can estimate the probability of not rejecting the PDDT with threshold again as

The value of increases with s as follows. After s steps, we throw “balls” (pairs added to PDDT) into bins; thus, the average number of “balls per bin” is

For S-boxes , we have and

When s is small in comparison to , we have a low probability of rejecting a PDDT; thus, the search space quickly branches out. With growing s, we increase the number of potential branches (up to ), as well as the probability of rejecting the PDDTs. Thus, the estimated width of the search tree on level s is

The number of potential endpoints of the search tree we are looking for is . Each of these points is connected to the root of the search tree, with the paths going through the level with the maximum width of the tree, denoted by . Thus, we need to go through the search tree on average -times, which is

As for each s, it is apparent that Algorithm 3 can always find the desired S-box (if it exists) faster than random search, which has an expected complexity of .

5. Experimental Results

In this section, we present experimental results to support our theoretical analysis of the algorithm. To obtain the presented results, we used a custom software called “SBox Tool” [49], developed in Python. This software can generate a selected number of S-boxes of a given size using different methods, analyze them, and export the results for further statistical processing.

In the first experiment, we analyzed a large number of randomly generated bijective S-boxes generated using Python’s random permutation method. Table 3 contains a cumulative distribution of -differentially uniform S-boxes. The values are based on a dataset of 10,000 randomly generated S-boxes. The experimental values are consistent with the estimates obtained by the “bins and balls” method presented in Table 2.

Table 3.

Cumulative distribution of -differentially uniform S-boxes based on a dataset of 10,000 randomly generated S-boxes.

We implemented the proposed method based on depth-first search (Algorithm 3) in the “S-box tool” software. We tested the method by generating datasets of 100 bijective S-boxes with different parameter settings. As the generated S-boxes were bijective, all of them are balanced. Although our method does not focus on other S-box properties, we have included the distribution of nonlinearity of the generated S-boxes for comparison with other methods based on the suggestion of an anonymous reviewer.

The summary of the results is presented in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8. We show two different methods of S-box generation: “Random” denotes simple random generation, while our new method is denoted by the label “P_DDT”. The parameter denotes the limit on partial DDT items allowed during the search. The “time” column is the average time required to generate an S-box with the selected method, while columns in “Nr. of -uniform S-boxes” show the distribution of the maximum value in the final DDT among the generated S-boxes (out of 100 generated S-boxes). Finally, the columns in “Nonlinearity” show the distribution of the nonlinearity among the generated S-boxes (out of 100 generated S-boxes).

Table 4.

Comparison of random generation of S-boxes with the proposed method based on partial DDT for an S-box size of .

Table 5.

Comparison of random generation of S-boxes with the proposed method based on partial DDT for an S-box size of .

Table 6.

Comparison of random generation of S-boxes with the proposed method based on partial DDT for an S-box size of .

Table 7.

Comparison of random generation of S-boxes with the proposed method based on partial DDT for an S-box size of .

Table 8.

Comparison of random generation of S-boxes with the proposed method based on partial DDT for on S-box size of .

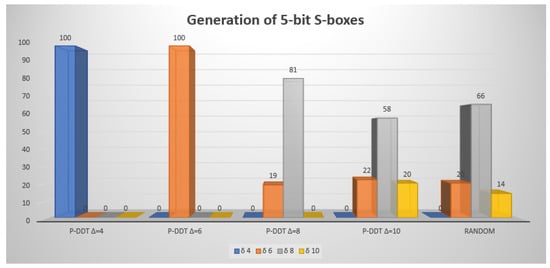

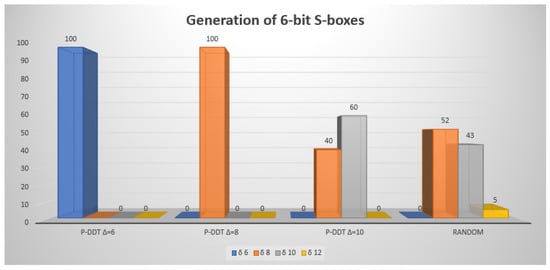

The results of S-box generation for and are available in graphical form in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. Note that we were unable to generate any S-boxes of size with the prescribed maximal DDT value of 4, as the program took too much time (more than 10 h) and did not produce any solution. Similar issues were encountered for S-boxes with and and with and .

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of comparison of the results obtained using different generation methods and different prescribed maximal value for an S-Box size of .

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of comparison of the results obtained using different generation methods and different prescribed maximal value for an SBox size of .

These results show that with the correct setting it is possible to generate S-boxes within a reasonable time that have better quality than those generated by a random search. The S-boxes generated with our method have similar nonlinearity to random S-boxes. The distribution of nonlinearity is slightly improved when setting smaller . This can be useful for future methods that might combine our algorithm with further post-processing focused on nonlinearity.

6. Discussion

In this article, we have introduced a new type of algorithm for constructing cryptographically strong S-boxes. The main idea of the proposed method is to determine S-box function values step by step and examine the partial Difference Distribution Table during the process. Setting and enforcing quality criteria during the S-box construction leads to a stochastic search algorithm with early rejection sampling. Our analysis of the algorithm, as confirmed by experimental results, shows that it outperforms purely random searches.

There are many open questions and open research topics related to our proposal. In our proposal, we focus solely on the differential properties of the S-box. To generate a good S-box that satisfies multiple criteria, these criteria can be evaluated after the algorithm reaches an S-box that fulfills the prescribed differential properties. If the S-box does not meet other criteria, it is possible to resume the original search after backtracking.

An open question is whether other criteria can be incorporated directly into the search based on the partial S-box. For certain criteria, this might be challenging. If we consider nonlinearity as an example, the nonlinearity is the minimum distance of any component of our function to any linear Boolean function. Adding additional value to a partial S-box can increase certain distances while decreasing others.

Another open question is whether it is possible to improve our method using stochastic search heuristics such as hill climbing, simulated annealing, or evolutionary algorithms. One direction to consider is changing the definition of the algorithm step from permuting two function values to filling in a partial S-box. It is, however, unclear what the fitness landscape would look like, as well as whether the optimization heuristics would provide an additional increase in performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and P.Z.; methodology, S.M. and P.Z.; software, S.M.; validation, S.M. and P.Z.; formal analysis, P.Z.; investigation, S.M. and P.Z.; resources, P.Z.; data curation, S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M. and P.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.M. and P.Z.; visualization, S.M. and P.Z.; supervision, P.Z.; project administration, P.Z.; funding acquisition, P.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under Contract no. APVV-19-0220.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions that improved this paper’s readability and content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AES | Advanced Encryption Standard |

| DDT | Difference Distribution Table |

| MC | Multiplicative Complexity |

| PDDT | Partial Difference Distribution Table |

| S-box | Substitution box |

References

- Shannon, C.E. Communication theory of secrecy systems. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1949, 28, 656–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlet, C. Boolean Functions for Cryptography and Coding Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, M. Linear cryptanalysis method for DES cipher. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT’93: Workshop on the Theory and Application of Cryptographic Techniques Lofthus, Norway, May 23–27, 1993 Proceedings 12; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; pp. 386–397. [Google Scholar]

- Biham, E.; Shamir, A. Differential cryptanalysis of DES-like cryptosystems. J. Cryptol. 1991, 4, 3–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, K.; Hayes, J. Balanced boolean functions. IEE Proc.-Comput. Digit. Tech. 1998, 145, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, A.F.; Tavares, S.E. On the design of S-boxes. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO’85 Proceedings; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 523–534. [Google Scholar]

- Forrié, R. The strict avalanche criterion: Spectral properties of Boolean functions and an extended definition. In Proceedings of the Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptography, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 21–25 August 1988; pp. 450–468. [Google Scholar]

- Braeken, A.; Preneel, B. On the Algebraic Immunity of Symmetric Boolean Functions. In Proceedings of the Progress in Cryptology—INDOCRYPT 2005; Maitra, S., Veni Madhavan, C.E., Venkatesan, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zajac, P.; Jókay, M. Multiplicative complexity of bijective 4× 4 S-boxes. Cryptogr. Commun. 2014, 6, 255–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, P.; Jókay, M. Cryptographic properties of small bijective S-boxes with respect to modular addition. Cryptogr. Commun. 2020, 12, 947–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheis, K.; Steinwandt, R.; Suárez Corona, A. Algebraic Properties of the Block Cipher DESL. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burwick, C.; Coppersmith, D.; D’Avignon, E.; Gennaro, R.; Halevi, S.; Jutla, C.; Matyas, S.M., Jr.; O’Connor, L.; Peyravian, M.; Safford, D.; et al. MARS-a candidate cipher for AES. NIST AES Propos. 1998, 268, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Antal, E.; Eliáš, M. Evolutionary computation in cryptanalysis of classical ciphers. Tatra Mt. Math. Publ. 2017, 70, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariot, L.; Jakobovic, D.; Bäck, T.; Hernandez-Castro, J. Artificial intelligence for the design of symmetric cryptographic primitives. In Security and Artificial Intelligence: A Crossdisciplinary Approach; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, J.A.; Jacob, J.L. Two-stage optimisation in the design of Boolean functions. In Proceedings of the Australasian Conference on Information Security and Privacy, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 10–12 July 2000; pp. 242–254. [Google Scholar]

- Millan, W.; Clark, A.; Dawson, E. Smart hill climbing finds better boolean functions. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Selected Areas in Cryptology, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 11–12 August 1997; Volume 63. [Google Scholar]

- Millan, W.; Burnett, L.; Carter, G.; Clark, A.; Dawson, E. Evolutionary heuristics for finding cryptographically strong S-boxes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information and Communications Security, EUROCRYPT 1998, Espoo, Finland, 31 May–4 June 1998; pp. 263–274. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, J.; Millan, W.; Dawson, E. Multi-objective optimisation of bijective S-boxes. New Gener. Comput. 2005, 23, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, A.; Wieclaw, L.; Poluyanenko, N.; Hamera, L.; Kandiy, S.; Lohachova, Y. Optimization of a Simulated Annealing Algorithm for S-Boxes Generating. Sensors 2022, 22, 6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souravlias, D.; Parsopoulos, K.; Meletiou, G. Designing Bijective S-boxes Using Algorithm Portfolios with Limited Time Budgets. Appl. Soft Comput. 2017, 59, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Qi, Z. Construction Method and Performance Analysis of Chaotic S-Box Based on a Memorable Simulated Annealing Algorithm. Symmetry 2020, 12, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, G.; Nikolov, N.; Nikova, S. Reversed genetic algorithms for generation of bijective s-boxes with good cryptographic properties. Cryptogr. Commun. 2016, 8, 247–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picek, S.; Mariot, L.; Yang, B.; Jakobovic, D.; Mentens, N. Design of S-boxes defined with cellular automata rules. In Proceedings of the Computing Frontiers Conference, Siena, Italy, 15–17 May 2017; pp. 409–414. [Google Scholar]

- Mariot, L.; Picek, S.; Leporati, A.; Jakobovic, D. Cellular automata based S-boxes. Cryptogr. Commun. 2019, 11, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freyre-Echevarría, A.; Alanezi, A.; Martínez-Díaz, I.; Ahmad, M.; Abd El-Latif, A.A.; Kolivand, H.; Razaq, A. An external parameter independent novel cost function for evolving bijective substitution-boxes. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesař, P. A new method for generating high non-linearity s-boxes. Radioengineering 2010, 19, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, R. Maximal recursive sequences with 3-valued recursive cross-correlation functions (Corresp.). IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1968, 14, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasami, T. The weight enumerators for several classes of subcodes of the 2nd order binary Reed-Muller codes. Inf. Control 1971, 18, 369–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracken, C.; Leander, G. A highly nonlinear differentially 4 uniform power mapping that permutes fields of even degree. Finite Fields Their Appl. 2010, 16, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, K.; Dillon, J.; McQuistan, M.; Wolfe, A. An APN permutation in dimension six. Finite Fields Theory Appl. 2010, 518, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Calderini, M. Differentially low uniform permutations from known 4-uniform functions. Des. Codes Cryptogr. 2021, 89, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, K. Perfect nonlinear S-boxes. In Proceedings of the Workshop on the Theory and Application of Cryptographic Techniques, Brighton, UK, 8–11 April 1991; pp. 378–386. [Google Scholar]

- Zahid, A.H.; Arshad, M.J. An Innovative Design of Substitution-Boxes Using Cubic Polynomial Mapping. Symmetry 2019, 11, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juremi, J.; Mahmod, R.; Sulaiman, S. A proposal for improving AES S-box with rotation and key-dependent. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Cyber Security, Cyber Warfare and Digital Forensic (CyberSec), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 26–28 June 2012; pp. 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, O.; Kole, D.; Rahaman, H. An Optimized S-Box for Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) Design. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Advances in Computing and Communications, Cochin, India, 9–11 August 2012; pp. 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zheng, H.; Hu, B.; Tang, H. Improved Lightweight Encryption Algorithm Based on Optimized S-Box. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Computational and Information Sciences, Shiyang, China, 21–23 June 2013; pp. 734–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Huang, L.; Zhong, H.; Chang, C.; Yang, W. An improved AES S-box and its performance analysis. Int. J. Innov. Comput. Inf. Control 2011, 7, 2291–2302. [Google Scholar]

- Niemiec, M.; Machowski, L. A new symmetric block cipher based on key-dependent S-boxes. In Proceedings of the 2012 IV International Congress on Ultra Modern Telecommunications and Control Systems, St. Petersburg, Russia, 3–5 October 2012; pp. 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazlauskas, K.; Smaliukas, R.; Vaicekauskas, G. A Novel Method to Design S-Boxes Based on Key-Dependent Permutation Schemes and its Quality Analysis. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazlauskas, K.; Vaicekauskas, G.; Smaliukas, R. An Algorithm for Key-Dependent S-Box Generation in Block Cipher System. Informatica 2015, 26, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, N.; Bansode, R. AES Based Text Encryption Using 12 Rounds with Dynamic Key Selection. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 79, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobeiri, M.; Maybodi, B. Introducing a new method in cryptography by using dynamic P-Box and S-Box (DPS method) based on modular calculation and key encryption. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2017, 12, 2946–2953. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, M.; Sinha, A. Enhanced-AES encryption mechanism with S-box splitting for wireless sensor networks. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grošek, O.; Nemoga, K.; Satko, L. Ideal Difference Tables from an Algebraic Point of View. Cryptology and Information Security, Proc. of VI RECSI, Teneriffe, Spain 2000; pp. 51–58. Ammendment to Criptologia y Seguridad de la Informacion (P. Caballero-Gil, C. Hern´andez-Goya), RA-MA, Madrid. 2000. pp. 453–454. Available online: https://www.casadellibro.com/libro-criptologia-y-seguridad-de-la-informacion-vi-recsi-actas/9788478974313/727589 (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Satko, L.; Grošek, O.; Nemoga, K. Extremal generalized S-boxes. Comput. Inform. 2003, 22, 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Zajac, P. Constructing S-boxes with low multiplicative complexity. Stud. Sci. Math. Hung. 2015, 52, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, A.; Knudsen, L.R.; Leander, G.; Paar, C.; Poschmann, A.; Robshaw, M.J.; Seurin, Y.; Vikkelsoe, C. PRESENT: An ultra-lightweight block cipher. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems, Vienna, Austria, 10–13 September 2007; pp. 450–466. [Google Scholar]

- Marsaglia, G.; Marsaglia, J.C. A New Derivation of Stirling’s Approximation to n! Am. Math. Mon. 1990, 97, 826–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marochok, S. Constructing S-Boxes with Prescribed Differential Distribution Table. Master’s Thesis, Slovak University of Technology in Bratislava, Bratislava, Slovakia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).