Abstract

Sorting permutations with various operations has applications in genetics and computer interconnection networks where an operation is specified by its generator set. A transposition tree is a spanning tree over n vertices . T denotes an operation in which each edge is a generator. A value assigned to a vertex is called a token or a marker. The markers on vertices u and v can be swapped only if the pair . The initial configuration consists of a bijection from the set of vertices to the set of markers . The goal is to sort the initial configuration of T, i.e., an input permutation, by applying the minimum number of swaps or moves in T. Computationally tractable optimal algorithms to sort permutations are known only for a few classes of transposition trees. We study a class of transposition trees called a broom and its variation a double broom. A single broom is a tree obtained by joining the centre vertex of a star with one of the two leaf vertices of a path graph. A double broom is an extension of a single broom where the centre vertex of a second star is connected to the terminal vertex of the path in a single broom. We propose a simple and efficient algorithm to obtain an optimal swap sequence to sort permutations with the transposition tree broom and a novel optimal algorithm to sort permutations with a double broom. We also introduce a new class of trees named millipede tree and prove that yields a tighter upper bound for sorting permutations with a balanced millipede tree compared to . Algorithms and are designed previously.

1. Introduction

Sorting permutations with various operations has applications in genetics and computer interconnection networks [1,2,3,4] and is an active field of research.Reversals, transpositions, prefix reversals, prefix transpositions have been extensively studied with respect to upper bounds, lower bounds, exact distances for all permutations in etc. Transposition tree is one such operation which has applications in solving puzzles and robot motion planning [5,6].

Hypercube architecture was a golden standard in 1980s for computer interconnection networks. Later, Akers and Krishnamurthy [1] proposed a transposition tree called star, and showed that the Cayley graph corresponding to star, called star graph can accommodate nodes and has diameter sub-logarithmic in number of vertices. Star graphs surpass the then topology Hypercube, both in scalability and diameter because the later can accommodate only vertices and has diameter logarithmic in number of vertices. Diameter is an important quality of service parameter deciding the latency of interconnection networks [7,8]. There is a natural trade-off between diameter and the cardinality of the generator set. That is, a larger generator set decreases the diameter and vice-versa. The diameter of a Cayley graph , can be trivially reduced to 1 if the degree of each node in is one less than the total number of nodes. However, if the number of symbols, i.e., the label length of a vertex is n, then this would require the degree to be and this is infeasible. Thus, a good balance is sought. In this regard, the degree of generated using any transposition tree is a relatively small value of and for some trees the diameter can be small as well. For example, for a star graph the diameter is [1]. Thus, Cayley networks were established as a better topology than hypercubes for interconnection networks. Cayley networks also possess other desirable features such as vertex symmetry and small diameter [1]. These are detailed in Heydemann [3], Lakshmivarahan et al. [4], and Xu [8].

In this article we study the problem of sorting permutations under the operation specified by specific transposition trees—single broom, double broom and millipede tree. A transposition tree is a spanning tree over n vertices . T denotes an operation in which each edge is a generator [1]. A value assigned to a vertex is called token or marker. The markers on vertices u and v can be swapped only if the pair . This is equivalent to applying the corresponding generator and is referred to as making a move. Since swap is symmetric, the edge is undirected. The initial configuration consists of a bijection from to ; i.e., from the set of vertices to the set of markers over the alphabet . That is, one can view each vertex as an index i in an array where some marker j resides. Thus, input consists of a permutation. The vertex is the home for the corresponding marker i and we seek to home all markers with minimum number of moves. Note that if for all i, then the permutation is sorted. Thus, the goal is to sort the initial configuration, i.e., an input permutation, by applying the minimum number of generators (or swaps or moves) of T. In the remainder of the article, ‘sorting’ refers to transforming a given permutation into the identity permutation with a minimum number of moves of T.

Example 1.

LetTbe a transposition tree withand. The generators are the permutations.

The computational complexity of sorting permutations with transposition trees is unknown in general. However, computationally tractable optimal algorithms to sort permutations are known for a few classes of transposition trees such as star [1], path [9], broom [5,6,10], etc.

We study the problem of sorting permutations with a single broom and a double broom transposition trees. A broom, also referred to as a single broom, is a transposition tree obtained by joining the center vertex of a star with one of the leaf vertices of a path. Several efficient optimal algorithms are known to sort permutations using a broom [5,10,11]. In Section 3 we design a new efficient optimal algorithm for sorting permutations using single broom. In Section 4 we design a novel efficient optimal algorithm for sorting permutations using double brooms. This algorithm is designed by extending the algorithm for single broom. The problem of sorting permutations using a new class of trees called millipede tree, is studied in Section 5. Section 6 demonstrates the limitation of the proposed algorithms when performed on an n-Broom providing a new direction for future research in the field of sorting permutations using transposition trees.

2. Preliminaries and Background

In this article, we employ the alphabet to generate the symmetric group . The permutation is the identity permutation in . An operation is specified by a generator set that is a subset of ; . Each permutation in the generator set is a generator. Let be a permutation in , and be a generator. Applying on yields another permutation, say . We say that transforms into . Given two permutations , and an operation , the minimum number of generators of required to transform into is called the distance from to under , denoted by and in general, it is hard to compute the same if the number of generators is two or more [12]. When is symmetric, then . If the target permutation is I, then is succinctly denoted as , which is called the distance of . Transforming into I is called as sorting , and thus is the number of generators required to sort parsimoniously. Let be a shortest sequence of generators such that . Then . That is, the number of moves required to transform into is same as that of transforming into the identity permutation I. Thus, the problem of finding minimum distance between two given permutations reduces to the problem of sorting a related permutation. If the target permutation is I, then is denoted as , which is called the distance of a single permutation .

Various operations have been studied in the past. Some of them are reversal, transposition, block interchange, etc. A block move operation moves a block; e.g., block transposition, suffix block transposition etc. A small sample of the research in this broad area follows. Christie studied sorting permutations by transpositions and proved a tighter lower bound based on the hurdles of the underlying cycle graph and designed a simpler 3/2-approximation algorithm [13]. The first non-trivial lower and upper bounds for prefix transposition distance over permutations were given in [2]. Chitturi et al. [14] shows how to compute the transposition distances of all permutations in in an amortized time of . Recently, subsets of permutations related to a certain type of block move operation have been counted [15]. These results are varied in type that employ distinct techniques such as dynamic programming and applications of graph properties, and constructs such as cycle graphs and adjacencies in permutations.

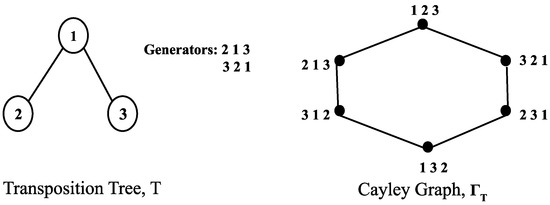

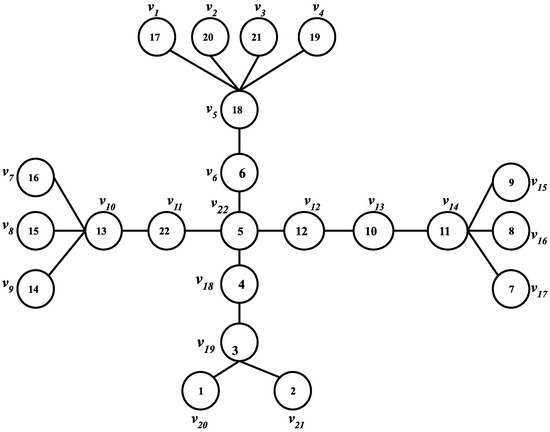

A Cayley graph under the operation T over is defined as follows. The vertex set V of consists of all permutations in . There is an edge from vertex u to vertex v if there is a generator such that . The distance between two permutations , and under the operation T, is equal to the number of edges in the shortest path between the corresponding vertices in . The diameter of , . A transposition tree in turn gives rise to a Cayley graph (refer Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A Transposition tree T and the corresponding Cayley graph .

The problem of sorting permutations using transposition trees is also known as token swapping on trees [5,6,11,16,17,18,19]. Given a tree T consisting of n vertices and edge set E, a configuration of T is an assignment of n distinct markers or tokens to the vertices of T. Tokens can be moved along the tree edges only. Given an initial configuration and a target configuration of a tree T, token swapping problem is to transform T from to with minimum number of moves.

A transposition tree with vertex set and edge set is called a path of length n. An optimal algorithm for sorting permutations using path requires k moves where k is the number of inversions in the given permutation [20]. The reverse permutation is the diametral permutation of that requires moves to sort. Another transposition tree studied in the past is star. A star (with center, say ) is a transposition tree with vertex set and edge set . Efficient optimal algorithms for sorting permutations using a star are known [1,21,22]. The optimum number of moves required to sort permutations using star is , where m is the number of un-homed leaf markers, and c is the number of permutation cycles of length , in the given permutation, consisting of un-homed leaf markers only [5]. When all cycles in a given permutation are of length 2, it takes the maximum number of moves to sort that permutation. Thus, the diameter of star graph is [1].

Generic algorithms to compute upper bounds (not necessarily tight) for sorting permutations with any given transposition tree have been studied. Akers and Krishnamurthy [1] propose the first known such algorithm that require exponential running time. Ganesan [23] proposed a method to compute an upper bound in exponential time which is an estimate of the upper bound by analyzing the structure of the transposition tree. Chitturi [24] designed two polynomial (O) time algorithms, and for computing upper bounds. The cumulative sum of upper bound values of and for all trees of a particular size were found to be tighter than the values provided by earlier methods. Furthermore, these algorithms solely analyzed the structure of the tree and were computationally efficient. Kraft [25] proposed randomized algorithms with polynomial running time which were looser than the other upper bounds. Uthan and Chitturi define a class of trees called [26] and prove an exact upper bound for the same.

3. Sorting Permutations with a Single Broom

In this section, we design a polynomial time optimal algorithm for sorting permutations using a single broom. A single broom is a tree obtained by joining the center vertex of a star with one of the two leaf vertices of a path graph, using a new edge. A single broom has n vertices, partitioned into two sets called star vertices , and path vertices , where . Note that the center of the star, i.e., is also a path node. Similarly, markers are partitioned into two sets called star markers and path markers. A star marker is a marker whose home is a star node, and a path marker is a marker whose home is a path node. A new efficient optimal algorithm called , for sorting permutations using single broom is given in Section 3.1.

3.1. Algorithm

Let be the star marker that is closest to its home residing on the path and be the largest path marker that is not homed. Our algorithm for single broom that transforms a given input configuration to a sorted configuration, consists of the following 3 steps in the given order.

- While (∃ a ), efficiently home ;

- While (∃ a ), efficiently home ;

- Efficiently home the markers in the star that need to be homed.

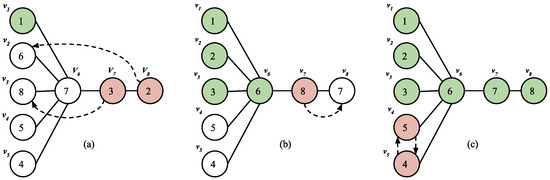

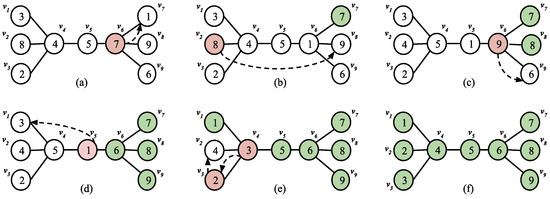

An illustration of algorithm for a single broom is given in Figure 2. In the initial setup, we have two unhomed star markers on path, i.e., 3 on and 2 on . is 3 in the first iteration and in the next it will be 2. Homing markers 3 and 2 take 5 swaps in total. Then, there will be no star markers residing on the path. Thus, we can start with Step 2 of our algorithm. is 8 and a swap with 7 homes both the markers. Only the star markers 5 and 4 at and respectively need to be homed. Our algorithm homes all markers in total of 9 swaps, exactly the same number of swaps that are taken by the algorithms of Biniaz et al. [5], Yamanaka et al. [6] and Vaughan [10].

Figure 2.

Illustration for Algorithm . The star vertices are , , , , and the path vertices are , , . (a) (i) = 3, Swaps = 2; (ii) = 2, Swaps = 3. (b) = 8, Swaps = 1. (c) Unhomed Markers are 5 and 4, Swaps = 3.

Step 1 and Step 2 of have the following properties:

- Star markers residing on the path always move to the left in the increasing order of their distances from their respective homes;

- A path marker moves right to its home; thereby moving the smaller path markers towards the center;

- Swap involving two star markers will not take place on a path edge.

The next section covers the analysis and correctness proof of the algorithm .

3.2. Analysis of

We begin our analysis for the number of swaps with Step 1. Let be the distance from to its home, where are the star markers residing on the path of the broom. , can reside either on the central node or on the rest of the nodes in the path. Note that homing a marker from central node to a star leaf takes exactly a single swap. is the total number of swaps executed in Step 1. Since, we home the nearest markers first, the distances of the markers that are homed subsequently do not increase. Thus, we have the following expression.

Observe that for Step 2, we are now left only with the path containing path markers. The total moves required on the path to place the markers at their desirable vertices is same as the number of inversions [9,27,28]. Let be the distance from the path marker to its home, where is the path marker residing on the path of the broom. is the total number of swaps executed in Step 2. Then, for the reason stated for in Step 1,

For the final step in , let be the number of permutation cycles not containing the center vertex that have a length ≥ 2 and be the number of markers in these cycles. These markers are not swapped in Step 1 or Step 2. So, as discussed before in Section 2, the number of swaps to home the star markers is .

, the total number of swaps performed in is:

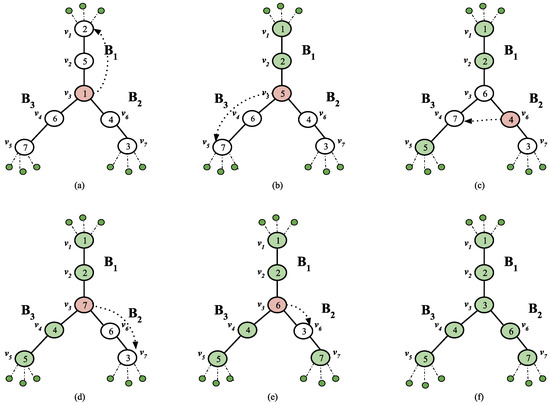

Step 1 of takes a distance-based approach in which is selected on the basis of its distance from the leaf nodes in the star. Step 2 obeys a value-based approach in which a maximum valued path marker is homed first. Biniaz’s, Kawahara’s and Vaughan’s algorithms are strictly based on a value-based approach and work in time. Figure 3 compares the traversal of markers in with the algorithms proposed by Biniaz and Kawahara.

Figure 3.

Comparison of algorithm with Biniaz’s and Kawahara’s algorithms. (a) = 3, Swaps = 2; = 4, Swaps = 3. (b) Maximum valued path token () = 9, Swaps = 3; = 8, Swaps = 3. (c) Maximum valued token () = 9, Swaps = 3; = 8, Star tokens = {3}, Swaps = 4. (d) = 5, Swaps = 1; = 2, Swaps = 4. (e) = 7, centered star chain = {4,5,3,7}, Swaps = 4. (f) = 7, Star tokens = {4,5}, Swaps = 3. (g) = 1, Swaps = 1; = 8, Swaps = 1, Total Swaps = 12. (h) = 6, centered star chain = {2,1,6}, Swaps = 2, Total Swaps = 12. (i) = 6, Star tokens = {2,1}, Swaps = 2, Total Swaps = 12.

Time complexity of can be expressed in terms of number of moves. The total number of markers possible in Step 1 is where S is the number of star vertices and P is the number of path vertices. The worst case of this step occurs when all the path nodes are occupied by star markers and the homes of these star markers are occupied by other star markers. The total number of moves required in Step 1 is . The worst case of Step 2 occurs when all P path markers need to be homed with a total swap count of . Solving the star in step 3 requires a maximum of moves. Since , Algorithm runs in time.

As the number of edges in a single broom is , the tree requires space, and the algorithm does not require any additional space.

3.3. Correctness of

In this section, we prove that finds an optimal swap sequence, , which always follows some interesting properties. To show that, is optimal, we first prove that these properties hold for a given marker on a broom and then apply induction on n.

Lemma 1.

An optimal path sequence will obey following properties:

- A pair of markers swap at most once.Proof.We prove it using contradiction. Suppose the swap sequence , contains the swap of twice at and . Modify S by deleting and . Then, for each swap where , replace x with y and vice-versa. Resulting swap sequence is shorter and achieves the same results. □

- Star markers that enter the star from path do so in the increasing order of their distance from center.Proof.Consider two star markers x and y residing on the path. Assume x and y are at a distance d and respectively from their home. Let S be the swap sequence containing the swap which swaps y and x on the path. Marker y will be homed after a swap with the marker residing on its home , call this swap where . Similarly x will be homed after a final swap with where . Call this intermediate configuration of markers as . We show how S can be modified in order to obtain an optimal sequence. To modify S, omit and carry out further swaps with x & y and & exchanged, until the swap . Observe that we have obtained the same marker configuration as in but with fewer swaps. □

- Two star markers will never swap on a path edge.Proof.Let us take x and y to be the star markers that swap on the path edge in S. We show how S can be modified to obtain a swap sequence with a lesser number of swaps on the path. After the swap of x and y in S, at some point of time, both x and y will get into the star. Let be a sub sequence of S, where y resides on a star leaf and x on the center node. To modify S, remove the swap of x and y and replace x with y and vice versa for the following swaps. Iterate this till the point is reached in S and add a swap of x and y. We have achieved the same target state, but a swap carried out on the path is removed and compensated by adding an additional swap in the star. □To illustrate the same, consider the swap sequence . Note that , where we have 2 at star leaf (say x) and 1 at the center (say y).If we omit the swap move (1, 2) and exchange , we get the modified swap sequence as (refer Figure 4). Followed by a swap move of x and y we achieve the same configuration as but the swap of x and y on path edge is replaced by a swap on star edge, resulting in lesser swaps on path edges.

Figure 4. (a) S = (1, 2), (2, 6), (2, 3), (1, 6), (1, 3), (1, 4). (b) Modified Swap Sequence = (1, 6), (1, 3), (2, 6), (2, 3).

Figure 4. (a) S = (1, 2), (2, 6), (2, 3), (1, 6), (1, 3), (1, 4). (b) Modified Swap Sequence = (1, 6), (1, 3), (2, 6), (2, 3). - In every swap on the path edge involving at least one path marker, the larger of the markers will move to the right.Proof.Considering the contradiction of the stated property, a bad swap involves moving a smaller valued path marker to the right and larger valued path marker to the left. Suppose S contains a bad swap. We show how S can be modified to obtain a new swap sequence which contains fewer swaps on the path. Assume smaller marker s is swapped to the right and larger marker l to the left. Property 1 restricts us from directly swapping them again. Therefore, marker l will move to the star leaf, then marker s to another star leaf and then l goes to the center of the star. Let us call this intermediate placement as . Now, to modify S, remove the swap of s and l, and continue with the preceding swaps with s and l exchanged until the state is reached. We have achieved the same target state, but a swap carried out on the path is removed and compensated for by adding an additional swap in the star; hence, reducing the swap count on the path edge. □

- No star marker moves past the first path edge from left to right.Proof.Let S include a swap in which a maker x moves past the first path edge to the right using a swap with a marker p. Let, is a swap belonging to S where which results in x reentering the star with the help of a swap with q. Taking the least possible j into account, we first establish that the marker q was residing on the star leaf during . Suppose q was on path node during , then q will lie on the right to x. Swaps involving x between and will only keep it on path nodes and not move it past the first path edge as per our assumption. Marker q is restricted to swap twice with x on the path edge as per Property 1, which proves that q lies on the right of x during , which is contradictory. We show how S can be modified to obtain a swap sequence with a lesser number of swaps on the path. Before , carry out a swap of x and q and continue with the following swaps till with x replaced with y and vice-versa. We have achieved the same target state but the swap on a path edge is removed and replaced by a swap on a star edge, hence reducing the number of swaps on the path edge. □

Theorem 1.

Algorithm computes an optimal swap sequence, i.e., a sorting sequence with the least possible number of swaps.

Proof.

We prove that our algorithm obtains an optimal swap sequence by applying induction on marker n. The base case is just a star S. Depending on the position of and , we consider different cases and prove them individually. Moreover, for the general induction step, we prove that swaps performed by and are a part of an optimal swap sequence.

Case (1): The initial position of is any path vertex other than the center vertex. Let be the optimal swap sequence. Property 2 and Property 3 ensures that n will never encounter a star marker on the path and hence it will only swap path markers on its way home. Let d be the distance from the initial position of marker n to its home vertex . So, contains d swaps which involves marker n. Let be the swap that homes marker n, therefore contain d swaps which includes marker n and swaps that do not include marker n. Call this intermediate configuration T. Create a separate swap sequence which homes n in first d swaps followed by swaps that do not involve n and then carry on with rest of the swaps from . Homing marker n does not alter the relative order of the remaining markers. Clearly, we have attained the same configuration state as in T, implying is an optimal swap sequence which is generated by our algorithm .

Consider be an optimal swap sequence which brings n to the center vertex. Observe that n can be placed on center in exactly swaps, where d is the distance of n from its home vertex on the star leaf. Let be the swap in that places marker n on the center and T be the intermediate configuration of the markers after . Create a swap sequence S that homes the marker n first in swaps and carries out the rest of the swaps, which does not include n. Clearly, you will get the same resulting configuration as of T with the same number of swaps. Hence, S is an optimal swap sequence.

Now, call the swap that homes n from the center vertex by swapping it with an arbitrary marker t residing on . Aforementioned discussion assumes that no swaps which involve star edges occur before . Otherwise, when n is initially placed on the center vertex or arrives at the center with the swap , it suffices to show that is optimal which does not alter the position of n before the swap . We do some modifications in to make this true. Split the subsequence into and , where the subsequence contains the swaps that occur on path edges and the subsequence contains the swaps that occur on star edges. Note that does not move marker n from its position and always places n back to the center. We can rearrange this subsequence containing and as there are no star markers moving towards the path and vice versa as mentioned in Property 5. After , carry out the swap and then perform the swaps in but with t and n exchanged. This results in the same placement of markers with no change in the swap count on the star and path. Hence, is same as the optimal sequence generated by our algorithm .

Case (2): After Step 1 of , it is important to observe that we are now only left with path markers as all the star markers are either homed or residing on star nodes (will be homed in Step 3). So, lets consider marker is on a path vertex, except the center vertex. According to the property proved before, will always move to the right, swapping the lesser value marker to the left. Let S be the swap sequence which contains swap moves for homing . Consider to be the swap which slots in its home and T be the configuration at that instance. Considering distance d between and its home, we can say will have d swaps involving and not involving (say be that swap sequence). To modify S, we first make d swap moves which involve , followed by and then , call this swap sequence . It is interesting to observe that initial d swap moves will not change the relative order of the rest of the path markers, post which, swap moves can be performed, ultimately resulting in the same configuration T; hence is optimal.

Now, suppose is on the center vertex. Let be the swap that marker n on the first path edge with an arbitrary marker t. If we assume there are no swaps before , we can just prove it with the above mentioned discussion in Case 2. Else, it suffices to show that is optimal and does not alter the position of n before . We modify to make this true. Split the subsequence into and , where contains the swaps that occur on path edges and contains the swaps that occur on star edges. Note that does not move marker n from its position and always places n back to the center. Additionally, as per Property 5 we can rearrange the subsequence containing and as there are no star markers moving towards the path and vice versa. To rearrange this subsequence, perform the swaps in , then the swap followed by the swaps in . While performing the saps in replace the marker n with marker t. This results in same placement of markers with no change in the swap count on the star and path edges; hence, is optimal and is the same as the one generated by our algorithm .

Case (3): As discussed before, for Step 3 the optimal number of swaps are where be the number of permutations that have a length ≥ 2 not involving the center vertex (say ) and be the number of markers that are in these permutations. In case of star, consider a sequence P of length ≥ 2 and the star vertices (say ). If , then the total swap count to sort P is . If , then the total swap count is . As the cycles in are not related to each other, gives the optimal swap count. □

4. Sorting Permutations with a Double Broom

A novel polynomial algorithm is designed in this section for optimally sorting permutations using a double broom. A double broom is a double star with their central vertices joined with a path (also known as a stem) [24]. Suppose double broom has a total of n vertices, on the left star, residing on the path (or stem) and on the right star. Note that we consider the central vertices and of the stars as path vertices of the double broom.

Let and be the left and right stars respectively, with corresponding center vertices and . Let and be the closest star marker residing on the path to and respectively and be the maximum valued unhomed path marker.

Our algorithm , that transforms a given input configuration to a sorted configuration, is as follows:

- While ∃ a marker, efficiently home ;

- While ∃ a marker, efficiently home ;

- (At this point, only the stem is left) While ∃ a marker, efficiently home ;

- Efficiently home the markers of and .

Note that any vertex to the right of (inclusive) will be considered as a path vertex from the perspective of a marker residing in . Similarly, any marker to the left of (including) will be a path vertex for markers in .

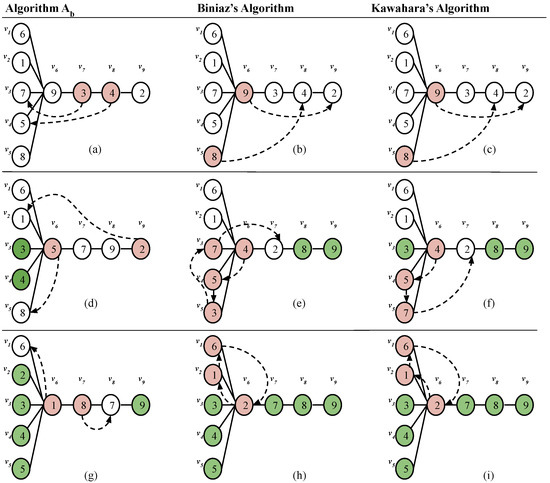

Our algorithm places each marker at its respective vertex in 10 swaps (refer Figure 5). It is also noteworthy to mention that the happy leaves are swapped in the process, hence abiding to the Happy Leaves conjecture. obeys following interesting properties which we use to analyse the algorithm in the next section.

Figure 5.

Illustration for Algorithm . (a) = 7, Swaps = 1. (b) = 8, Swaps = 4. (c) = 9, Swaps = 1. (d) = 1, Swaps = 2. (e) = 3, Swaps = 1, = 2, Swaps = 1. (f) All markers are homed. Total Swaps = 10.

- Swap of two star markers belonging to a same star will never take place on a path edge;

- Stem marker moves right to its home, swapping smaller markers to the left.

4.1. Analysis of

Let be the total number of swaps performed in . We first consider step 4 of our algorithm. For , let be the non trivial cycles and be the number of markers in these cycles. Similarly, for , let be the non trivial cycles and be the number of markers in these cycles. As these markers retain their relative positions till Step 4 of our algorithm, our total number of swaps in Step 4 will be:

Let and be the total number of swaps carried out in Step 1 and Step 2 respectively. To analyse and , we allocate each of its swaps to closest star marker residing on the path and involved in the swap. Then,

where is the number of swaps allocated to closest star marker . For , define to be the distance from a star leaf to ’s home. With reference to the initial configuration state of the markers, let be the number of markers smaller than and on the right of .

Similarly, for , define to be the distance from a star leaf to ’s home and let be the number of markers greater than and on the right of .

Claim 1.

is the minimum ofand

Proof.

If or are at star leaf of or respectively in the current configuration of markers, we can say = implying . = , where and thus validating our claims. □

Claim 2.

is the minimum ofand.

Proof.

If is not at a star leaf of , we can say . Similarly, in case of , justifying the above mentioned claims. □

Claim 3.

In algorithm, swapping Steps 1 and 2 does not alter the swap count.

Proof.

In the initial configuration, let and to be the number of star markers residing in and on the path, respectively, whose homes are in . Similarly, let and be the number of star markers residing in and on the path respectively whose homes are in . Path markers can be in , , or on the path. Let the total swaps required for homing path markers be , where , , and let be the swap count for homing markers residing on the path, and respectively.

Case (1): Perform Step 1 of followed by Step 2. Moving towards the right, shifts the markers it encounters on the way to the left. This shift decreases and . Path markers entering into (say ) during a swap increase P and the number of path tokens leaving , i.e., will result in the decrease of P.

In Step 2, can encounter only path markers on the way home. shifts both markers which entered into in Step 1 and markers to the right.

At this point, we are now left only with as all the path markers are now residing on the path, for which the swap count will be the total number of inversions.

Case (2): Perform Step 2 of followed by Step 1. Moving towards the left, shifts the markers it encounters on the way to the right. This shift decreases and . Path markers entering into (say ) during a swap increase P and the number of path tokens leaving i.e., will result in the decrease of P.

In Step 2, can encounter only path markers on the way home. shifts both markers which entered into in Step 1 and markers to the left.

At this point, we are now left only with , the same as what we arrived at in Case 1. Markers traversing towards in Step 1 of shift all the markers whose home is in to the left. Similarly, markers traversing towards shift all markers to the right; hence, there are no bad swaps and the properties of are obeyed. □

In Step 3, observe that we are now left only with the stem markers. The total number of swaps on path are the same as the number of inversions required to place the markers at their desirable vertex. Let be the distance from the marker to its home. Similarly, we can say:

where are the total number of swaps in Step 3 and are the markers residing on the stem of the broom.

Lemma 2.

Similar to algorithm , time complexity of is also expressed in terms of the number of moves. The worst case of Step 1 occurs when all path vertices are occupied by star markers of and the homes of these star markers are occupied by other markers. The total number of moves required in this case is , where and P are the number of vertices in and path respectively. The worst case of Step 2 occurs when all the path vertices are occupied by star markers of and the homes of these star markers are occupied by other markers. The total number of moves required in this case is , where is the number of vertices in . In the worst case of Step 3, moves are required to home the P path markers. Step 4 requires moves at most. Since , Algorithm runs in time. The tree requires space, and the algorithm does not require any additional space.

4.2. Correctness of

In this section, we prove that our algorithm generates an optimal swap sequence on a double broom. Initially, we discuss some properties required to prove the correctness of our algorithm. Section 1 covers the proof for properties 1 to 5.

- Two same markers will not swap more than once;

- Star markers belonging to the respective star enter into the star in the increasing order of their distances from that star;

- Star markers belonging to the respective star never swap with each other on the path edges. Note that the star marker belonging to treats the edges of the as path edges and vice-versa;

- Swaps on the stem involving at least one stem marker—the larger of the markers will move to the right’

- No star marker residing on one if its star vertices moves past the first path edge;

- In a swap s = () where and , l always moves to the left and r to the right.

Proof

We prove it by contradiction. A involves moving l to the right and r to the left. Suppose S has a on the path. We show how S can be modified to obtain a new swap sequence which contains fewer swaps on the path. Property 1 restricts us from directly swapping them again. Therefore, marker r will move to the star leaf of (or l will move to the star leaf of ), then marker l to another star leaf of (or r will move to another star leaf of ) and then l goes to the center of (or r will move to the center of ). Let us call this intermediate placement of markers . To modify S, omit the swap of l and r, and carry on with the preceding swaps with l and r exchanged until the state is reached. This results in the same swap count, though a swap on star replaces a swap on path. □

Theorem 2.

Algorithm generates an optimal swap sequence, i.e., a sorting sequence with the least possible number of swaps.

Proof.

We prove that our algorithm obtains an optimal swap sequence by applying induction on marker n. For the base case, the double broom has no path edges and it is only a star (either or ). It is interesting to note that, this algorithm is equivalent to writing:

- While ∃ a marker, home .

- Run

- Solve

As discussed in the previous section, obtains an optimal solution and we are now left to prove only in case of . Depending on the position of , we consider different cases and prove them individually. In the general induction step, we prove that swaps performed by are part of the optimal swap sequence.

Case (1): Assume marker n = is initially placed on a stem vertex, except the center node of . Let be the optimal swap sequence. Property 2 and Property 3 ensures that n will never swap with a star marker on its way home in . Let d be the distance from the position of marker n to its home . So, there are exactly d swaps in which contain marker n. Let be the swap that homes marker n, therefore , contain d swaps which includes marker n and swaps that do not include marker n. Let this intermediate configuration be T. Create a separate swap sequence which takes the initial d swaps to homes n, followed by swaps that do not involve n and then carry on with rest of the swaps from . Initial d swaps leave the remaining markers in the same relative order. We have attained the same configuration state as in T implying the swap sequence is optimal and is same as the one generated by our algorithm .

Case (2): Consider be an optimal swap sequence which brings n to the center vertex. Observe that n can be placed on center in exactly swaps, where d is the distance of n from its home vertex on the star leaf. Let be the swap in that places marker n on the center and T be the intermediate configuration of the markers after . Create a swap sequence S that homes n first in swaps and carries out the rest of the swaps which does not include n. Clearly, you will get the same resulting configuration as of T with the same number of swaps. Hence, S is an optimal swap sequence.

Now, call the swap that homes n from the center vertex of by swapping it with an arbitrary marker t residing on . Previous discussion assumes that no swaps occur on the star edges before . Otherwise, when n is initially placed on the center vertex or arrives at the center with the swap it suffices to show that is optimal and does not alter the position of n before the swap . We do some modifications in to make this true. Split the subsequence into two subsequences and . contains the swaps that occurs on path edges and contains the swaps that occurs on star edges. Note that does not move marker n from its position and always places n back to the center. We can rearrange this subsequence containing and as no star markers move towards the path and vice versa, due to the aforementioned Property 5. After , carry out the swap and then perform the swaps in but with t in place of n. Note that we can use the same argument for n placed on and prove the optimality of the subsequence as in Case 1. Clearly, this gives the same placement of markers with same swap count on the star and path. Hence, is optimal and is same as the sequence generated by our algorithm .

Case (3): Assume is on the leaf vertex of . Let t be the marker on the center vertex and be the swap involving n and t. If there are no swaps before , then just perform and use the argument from Case 2 to prove the optimality of the sequence . Otherwise, suppose there exists a cyclic permutation of length for the markers residing in . Cycles which do not include n are not taken into consideration, as solving those cycles will not alter the position of n. Similar to the argument used for star, we prove that the can be solved in swaps. Each marker in C is far away by two swaps from its home, so the total distance is . However, as one swap helps us move two markers near to their respective homes, our requirement is only swaps. Interestingly, the initial and the final swap of moves only one marker which belongs to . Adding the swap of n and t results in a total of swaps contradictory to swaps to sort . □

5. Analysis of Algorithm D* on Millipede Tree

The first known upper bound , for sorting permutations using transposition trees, was computed by Akers and Krishnamurthy [1] in 1989. The time complexity for calculating is , since it performs pair wise distance computation of each of the possible permutations. Subsequently, various polynomial time approximation algorithms were designed [23,24,25,29,30]. Chitturi introduced algorithm in [24] which finds the upper bound in polynomial time, which is the tightest known upper bound when the upper bounds of all trees are summed together. Subsequently, algorithm which identifies corresponding the upper bound was designed in [29]. It was shown that is tighter for balanced-starburst tree [29]. In [31], an analysis of both and was performed and shows that is tighter for full binary tree too. In this section we define a class of trees called millipede tree for which is tighter, compared to .

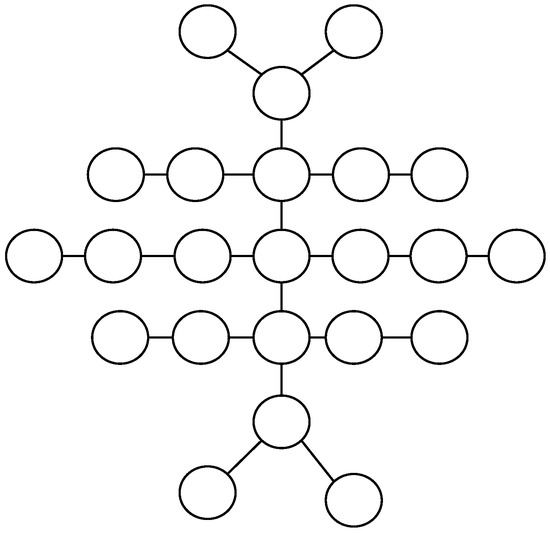

A millipede tree is obtained by connecting the centre vertices of k path graphs arranged in the order, such that k is odd and the number of vertices in is given by the following function:

The diameter of is and the total number of vertices . is the center of the tree. The center has an eccentricity of .

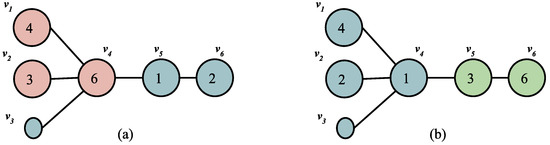

We call the subtree above the vertex the upper millipede tree and the subtree below the lower millipede tree(refer Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Millipede tree, .

5.1. Algorithm

Throughout this section, we employ the terminology used in [1,24,29]. The eccentricity of a node u in , denoted by , is equal to the maximum value of the distance between u and any other node . The Center of a tree is a node with minimum eccentricity. The Diameter of T denoted as is the maximum among all the eccentricities. The set of vertices in with maximum eccentricity is defined as S. S is a subset of the leaf nodes. Algorithm deletes a set of leaf nodes , and calculates the upper bound required to home markers destined to the vertices in L. This process is continued till the graph becomes a star. The exact upper bound for a star is defined in [1], which is . Let S be divided into kclusters such that for any in , . Let X be any one of the k clusters. When the vertices of are deleted, then the diameter of the resultant tree decreases by one. The maximum distance a marker need to travel to be homed is the diameter of the tree, . Thus, deletes all the vertices of S, except the largest cluster , so that minimum number of markers are homed at the current diameter and then reduces the diameter by one. Since the markers homed to the leaves are not required to move further, algorithm deletes such leaves from the tree. Two variants of , named and were introduced. removes the entire set S if and removes S if , where . , which calculates the upper bound [29] is an improved version of . If , then at most markers need moves each to be homed. Algorithm works based on this idea. The proof can be seen in [29,31]. deletes nodes in cost and the remaining nodes in the cluster with cost. It is observed that the is tighter than when is between one-third and half of the total size of set .

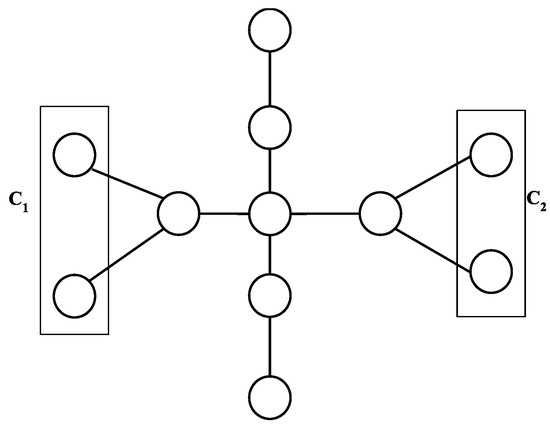

5.2. Analysis and Results

It is observed that would yield a tighter upper bound than for a millipede tree. In the first iteration of on , the set S contains all the leaf nodes and results in two clusters— and . and are of same size which contain the leaf nodes in the upper and lower millipede trees respectively (refer Figure 7). The terminal nodes in the path graph are not part of any cluster. Note that, deleting or will result in isomorphic trees (refer Figure 8). Since the size of the largest cluster ( or ) is less than half of the size of S, only markers need to be homed in cost and the remaining markers in the set S can be homed at a cost of . This results in two steps and for calculating the total cost in the iteration:

Figure 7.

Clusters in .

Figure 8.

(a) When is chosen as . (b) When is chosen as .

:

; : .

| Algorithm 1 Algorithm [29] |

|

In the case of , there is only one step and all the markers of C are homed in cost. Two nodes are homed in Step resulting in an improvement of 1 in . As and delete all the vertices of , the resultant tree after the first iteration is same for both. Similarly, every odd iteration generate two clusters and result in an improvement of 1. The second iteration generates two clusters and , which contain the leaf nodes of the upper and lower millipede trees respectively. Even iterations do not result in any improvement in , as both the algorithms remove nodes in cost. Refer Table 1, where is the cost per node for homing nodes in Algorithm , is the cost per node for homing nodes in Algorithm , is the cost per node for homing nodes in Algorithm and is the cost per node for homing nodes in Algorithm . After iterations in , the tree becomes a star, which is the base case of both the algorithms.

Table 1.

Cost of removing nodes in and on millipede tree.

As mentioned above, where is the cost computed in and is the cost computed in , for every odd iteration. Therefore after the ith iteration, the total improvement is .

The upper bound value for all millipede trees with diameters up to 16 was computed for both and . The results (refer Table 2) show that, is smaller than . and are deterministic for a millipede tree since the choice of vertices for deletion in each iteration does not alter the upper bound. establishes the fact that is tighter on a millipede tree as the difference is directly proportional to the initial diameter d. In terms of the number of path graphs k in the tree , can also be written as .

Table 2.

Comparison of and on millipede trees with various diameters.

Theorem 3.

for a millipede tree .

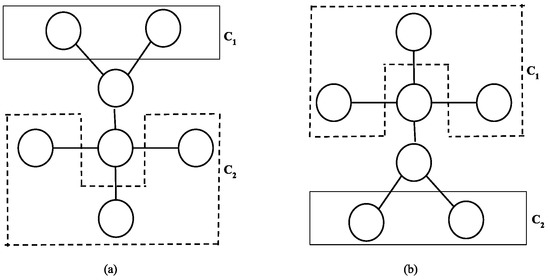

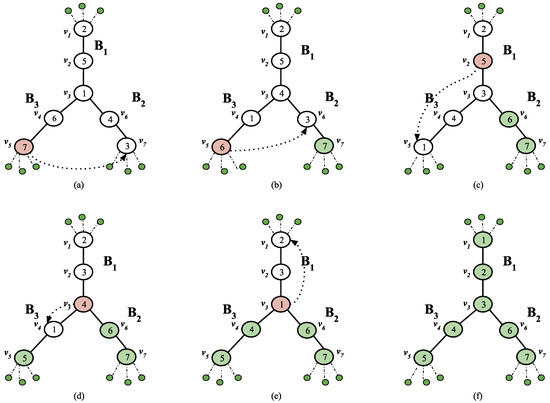

6. Scope for Future Research

An n-Broom (where n ≥ 3) is a transposition tree where the terminal node of the paths of n single brooms are connected to a common node. Figure 9 shows one of the possible 4-Brooms. Figure 10 and Figure 11 show two different possible swap sequences for a 3-Broom, where brooms , and are connected to the common node . Assume that all the star markers are homed, and only the path markers are left to be homed. The figures do not show the star markers, since these markers need not be swapped while homing the path markers. Figure 10 and Figure 11 n-Broom impacts the total swap count. Homing the path markers in before the path markers in (Figure 11) resulted in a non-optimal swap sequence which required more swaps than the swaps executed in Figure 10. Hence, does not guarantee an optimal swap sequence for an n-broom. Thus, designing a polynomial time optimal algorithm for sorting permutations on n-brooms is open.

Figure 9.

n-Broom with n = 4 and as the connecting node.

Figure 10.

One possible swap sequence of path markers on a 3-Broom shown in (a). (a) Homing 1, Swaps = 2. (b) Homing 5, Swaps = 2. (c) Homing 4, Swaps = 2. (d) Homing 7, Swaps = 2. (e) Homing 6, Swaps = 1. (f) All markers are homed. Total Swaps = 9.

Figure 11.

Another possible swap sequence of path markers on the 3-Broom shown in Figure 10a. (a) Homing 7, Swaps = 4. (b) Homing 6, Swaps = 3. (c) Homing 5, Swaps = 3. (d) Homing 4, Swaps = 1. (e) Homing 1, Swaps = 2. (f) All markers are homed. Total Swaps = 13.

7. Conclusions

Sorting permutations using various operations has applications in computer interconnection networks and evolutionary biology. We designed a simpler time algorithm for sorting permutations using the transposition tree single broom. We designed a novel time algorithm for optimally sorting permutations with a double broom and proved its correctness.

We defined a new class of trees that we call millipede. Among the existing generic algorithms that sort with any given transposition tree, and are the tightest and are comparable to one another. We showed that yields a tighter upper bound than for a balanced millipede tree.

We also demonstrated how algorithm does not yield an optimal swap sequence in the case of n-Broom, concluding that a polynomial-time algorithm for n-broom can be a subject of future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.T.S. and B.C.; Writing—original draft, I.T.S.; Writing—review & editing, I.T.S. and B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Akers, S.B.; Krishnamurthy, B. A group-theoretic model for symmetric interconnection networks. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1989, 38, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitturi, B. On Transforming Sequences. University of Texas at Dallas. 2007. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Bhadrachalam-Chitturi/publication/308524758_ON_TRANSFORMING_SEQUENCES/links/57e64be408aed7fe4667bb11/ON-TRANSFORMING-SEQUENCES.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2017).

- Heydemann, M.-C. Cayley graphs and interconnection networks. In Graph Symmetry; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1997; pp. 167–224. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmivarahan, S.; Jwo, J.-S.; Dhall, S.K. Symmetry in interconnection networks based on Cayley graphs of permutation groups: A survey. Parallel Comput. 1993, 19, 361–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, B.A.; Lubiw, K.; Masárová, A.; Miltzow, Z.; Mondal, T.; Naredl, D.; Murty, A.; Josef, T.; Alexi, T. Token Swapping on Trees. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.06981. [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka, K.; Demaine, E.D.; Ito, T.; Kawahara, J.; Kiyomi, M.; Okamoto, Y.; Saitoh, T.; Suzuki, A.; Uchizawa, K.; Uno, T. Swapping labeled tokens on graphs. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2015, 586, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooperman, G.; Finkelstein, L. New methods for using Cayley graphs in interconnection networks. Discret. Appl. Math. 1992, 37–38, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Topological Structure and Analysis of Interconnection Networks; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Knuth, D.E. The Art of Computer Programming: Sorting and Searching, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 1997; pp. 426–458. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, T.P. Factoring a permutation on a broom. J. Comb. Math. Comb. Comput. 1999, 30, 129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara, J.; Saitoh, T.; Yoshinaka, R. The Time Complexity of the Token Swapping Problem and Its Parallel Variants. Walcom Algorithms Comput. 2017, 448–459. [Google Scholar]

- Jerrum, M.R. The complexity of finding minimum-length generator sequences. Theor. Comput. Sci. 1985, 36, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, D.A. Genome Rearrangement Problems; The University of Glasgow: Glasgow, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chitturi, B.; Das, P. Sorting permutations with transpositions in O(n3) amortized time. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2019, 766, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitturi, B. Computing cardinalities of subsets of Sn with k adjacencies. JCMCC 2020, 113, 183–195. [Google Scholar]

- Malavika, J.; Scaria, S.; Indulekha, T.S. On Token Swapping in Labeled Tree. In Proceedings of the 2021 Third International Conference on Inventive Research in Computing Applications (ICIRCA), Coimbatore, India, 2–4 September 2021; pp. 940–945. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet, É.; Miltzow, T.; Rzazewski, P. Complexity of Token Swapping and Its Variants. Algorithmica 2017, 80, 2656–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, J.; Saitoh, T.; Yoshinaka, R. The Time Complexity of Permutation Routing via Matching, Token Swapping and a Variant. JGAA 2019, 23, 29–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltzow, T.; Narins, L.; Okamoto, Y.; Rote, G.; Thomas, A.; Uno, T. Approximation and hardness of token swapping. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual European Symposium on Algorithms (ESA 2016), Aarhus, Denmark, 22–24 August 2016; Volume 57. [Google Scholar]

- Cayley, A. LXXVII. Note on the theory of permutations. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1849, 34, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, I. Reduced decompositions of permutations in terms of star transpositions, generalized catalan numbers and k-ARY trees. Discrete Math. 1999, 204, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portier, F.J.; Vaughan, T.P. Whitney Numbers of the Second Kind for the Star Poset. Eur. J. Comb. 1990, 11, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, A. An efficient algorithm for the diameter of cayley graphs generated by transposition trees. Aeng Int. J. Appl. Math. 2012, 42, 214–223. [Google Scholar]

- Chitturi, B. Upper Bounds For Sorting Permutations With A Transposition Tree. Discret. Math. Algorithm. Appl. 2013, 5, 1350003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, B. Diameters of Cayley graphs generated by transposition trees. Discret. Appl. Math. 2015, 184, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthan, S.; Chitturi, B. Bounding the diameter of Cayley graphs generated by specific transposition trees. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI), Udupi, India, 13–16 September 2017; pp. 1242–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Balcza, L. On inversions and cycles in permutations. Period. Polytech. Civ. Eng. 1992, 36, 369–374. [Google Scholar]

- Edelman, P.H. On Inversions and Cycles in Permutations. Eur. J. Comb. 1987, 8, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chitturi, B.; Indulekha, T.S. Sorting permutations with a transposition tree. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Modeling Simulation and Applied Optimization (ICMSAO), Manama, Bahrain, 15–17 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Das, D.K.; Chitturi, B.; Kuppili, S.S. An Upper Bound For Sorting Permutations With A Transposition Tree. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 171, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indulekha, T.S.; Chitturi, B. Analysis of Algorithm δ* on full binary trees. In Proceedings of the 2019 Second International Conference on Advanced Computational and Communication Paradigms (ICACCP), Gangtok, India, 25–28 February 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).