Abstract

The development of robotic applications for agricultural environments has several problems which are not present in the robotic systems used for indoor environments. Some of these problems can be solved with an efficient navigation system. In this paper, a new system is introduced to improve the navigation tasks for those robots which operate in agricultural environments. Concretely, the paper focuses on the problem related to the autonomous mapping of agricultural parcels (i.e., an orange grove). The map created by the system will be used to help the robots navigate into the parcel to perform maintenance tasks such as weed removal, harvest, or pest inspection. The proposed system connects to a satellite positioning service to obtain the real coordinates where the robotic system is placed. With these coordinates, the parcel information is downloaded from an online map service in order to autonomously obtain a map of the parcel in a readable format for the robot. Finally, path planning is performed by means of Fast Marching techniques using the robot or a team of two robots. This paper introduces the proof-of-concept and describes all the necessary steps and algorithms to obtain the path planning just from the initial coordinates of the robot.

1. Introduction

Agriculture is an important industry to the national economy in Spain, Italy, France, Switzerland, and other countries around the world. In the case of Spain, the primary forms of property holding are large estates and tiny land plots. According to the 2009 National Agricultural Census (http://www.ine.es/jaxi/Tabla.htm?path=/t01/p042/ccaa_prov/l0/&file=010101.px&L=0), of the agricultural terrain was held in properties of 5 or more hectares. Those farms are located in those zones which are mainly devoted to permanent crops: orchards, olive groves, citric groves, and vineyards. However, only in the area of Valencia (Spain), there are more than 100,000 small farms with an exploitation area lower than 1 hectare. This represents 50% of the total number of farms located in Valencia and 20% of the small farms located in Spain.

The agricultural industry is suffering diverse problems which are causing the progressive leave of fields, groves, and orchards in Spain. The main problems are the ageing of the agricultural active population, the low incorporation of young people, and the financial crisis suffered in early 2010. The bitter campaign for the Spanish citrus sector in 2019, where the average price has been around 35% lower than previous campaigns, is accelerating the abandonment of small citrus groves in Valencia. This drives to an undesirable scenario where the active and the abandoned farms coexist. A small active grove next to abandoned ones is more prone to being affected by plagues or, even, wildfires. Thus, more effective maintenance tasks are needed.

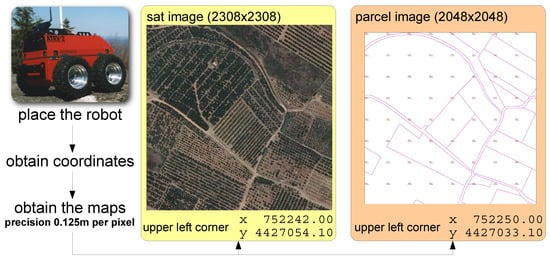

One possible solution to minimize costs is to automatize maintenance and surveillance tasks. This can be done by teams of robots in large farms. In most large farms, the structure and the distribution of elements (e.g., citric trees) are homogeneous and well known. In contrast, in those areas where the small farms are located, the structure and distribution depend on the owners (see Figure 1), who usually are not technology-friendly and do not have digital information about their farms. Thus, to ease the operation of maintenance robots in such kinds of farms, a procedure to automatically retrieve information about where they have to operate is needed.

Figure 1.

Sample of small farms, including abandoned ones, in Valencia (Spain).

Remote sensing can be used to extract information about the farm. Blazquez et al. [1] introduced a manual methodology for citrus grove mapping using infrared aerial imagery. However, access to aerial imagery is often limited and using dedicated satellite imagery is not widely used for navigation tasks. As the authors of Reference [2] stated, multispectral remote imagery can provide accurate weed maps but the operating costs might be prohibitive.

This paper introduces a proof-of-concept where we target the combination of public satellite imagery along with parcel information provided by governmental institutions. In particular, the system uses the maps and orthophotos provided by SIGPAC (Sistema de Información Geográfica de parcelas agrícolas) to minimize operational costs. The proposed approach in the present paper is similar to the system introduced in Reference [3] with some differences. First, it uses public open data. Second, our system adopts only a binarization of the remote image instead of using classifiers because determining the kind of tree or grove is not critical. Third, the orange tree lines are also determined in the proposed mapping.

The remaining of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 shows some related and state-of-the-art works in this field. Section 3 describes the algorithms to extract satellite imagery and the mask of the parcel where the path planning is to be determined. Section 4 describes the steps required to autonomously determine the path planning according to the available information (reduced satellite imagery, cadastral information, and the current position of the autonomous robots). Although this work lacks experimental validation, Section 5 shows an example of the intermediate and final outputs on a real case as a proof of concept. Finally, a few cases are introduced to show the potential of the proposed path planning generated for a single robot and a team composed of two robots.

2. State of the Art

As already mentioned, the agricultural sector is one of the least technologically developed. Nonetheless, some robotic systems have been already proposed for harvesting [4,5,6,7] and for weed control/elimination [8,9,10,11]. All these tasks have a common element: the robotic systems should autonomously navigate.

A major part of related works on autonomous mapping is based on remote imagery. An interesting review can be found in Reference [2]. However, as the authors stated, hyperspectral images produce highly accurate maps but this technology might not be portable because of the prohibitive operating costs. Similarly, other approaches (e.g., imagery provided by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) [12] or airborne high spatial resolution hyperspectral images combined with Light Radar (LiDAR) data [13]) also have high operating costs. Amores et al. [3] introduced a classification system to perform mapping tasks on different types of groves using airborne colour images and orthophotos.

A semi-autonomous navigation system controlled by a human expert operator was introduced by Stentz et al. [14]. This navigation was proposed to supervise the path planning and navigation of a fleet of tractors using the information provided by vision sensors. During its execution, the system determines the route segment where each tractor should drive trough to perform crop spraying. Each segment is assigned by tracking positions and speeds previously stored. When an obstacle is detected, the tractor stops and the human operator decides the actions to be carried out.

A sensor fusion system using a fuzzy-logic-enhanced Kalman Filter was introduced by Subramanian et al. [15]. The paper aimed to fuse the information of different sensor systems for pathfinding. They used machine vision, LiDAR, an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), and a speedometer to guide an autonomous tractor trough citrus grove alleyways. The system was successfully tested on curved paths at different speeds.

In the research introduced by Rankin et al. [16], a set of binary detectors were implemented to detect obstacles, tree trunks, and tree lines, among other entities for off-road autonomous navigation by an unmanned ground vehicle (UGV). A compact terrain map was built from each frame of stereo images. According to the authors, the detectors label terrain as either traversable or non-traversable. Then, a cost analysis assigns a cost to driving over a discrete patch of terrain.

Bakker et al. [17] introduced a Real Time Kinematic Differential Global Positioning System-based autonomous field navigation system including automated headland turns. It was developed for crop-row mapping using machine vision. Concretely, they used a colour camera mounted at 0.9 m above the ground with an inclination of for the vertical. Results from the field experiments showed that the system can be guided along a defined path with cm precision using an autonomous robot navigating in a crop row.

A navigation system for outdoor mobile robots using GPS for global positioning and GPRS for communication was introduced in Reference [18]. A server–client architecture was proposed and its hardware, communication software, and movement algorithms were described. The results on two typical scenarios showed the robot manoeuvring and depicted the behaviour of the novel implemented algorithms.

Rovira-Mas et al. [19] proposed a framework to build globally referenced navigation grids by combining global positioning and stereo vision. First, the creation of local grids occurs in real time right after the stereo images have been captured by the vehicle in the field. In this way, perception data is effectively condensed in regular grids. Then, global referencing allows the discontinuous appendage of data to succeed in the completion and updating of navigation grids over time over multiple mapping sessions. With this, global references are extracted for every cell of the grid. This methodology takes the advantages of local and global information so navigation is highly benefited. Finally, the whole system was successfully validated in a commercial vineyard.

In Reference [20], the authors proposed a novel field-of-view machine system to control a small agricultural robot that navigates between rows in cornfields. The robot was guided using a camera with pitch and yaw motion control in the prototype, and it moved to accommodate the near, far, and lateral fields of view mode.

The approach we propose differs from others since satellite imagery and a camera placed in the autonomous robot (see References [21,22]) are combined for advanced navigation. GPS sensor and satellite imagery are used (1) to acquire global knowledge of the groves where the robots should navigate and (2) to autonomously generate a first path planning. This first path planning contains the route where each robotic system should navigate. Moreover, the local vision system at the autonomous robot, that is composed by a colour Charge Coupled Device (CCD) camera with auto iris control, is used to add real-time information and to allow the robot to navigate centred in the path (see Reference [21]). Although the first path planning already introduces a route to navigate centred in the paths, local vision provides more precise information. We can benefit from combining global and local information; we can establish a first path planning from remote imagery which can be updated by local imagery captured in real time.

4. Results on a Real Case: Proof-of-Concept Validation

The previous section introduced the algorithms to obtain the path that a robot or system of two robots have to follow to cover the whole citric grove for, for instance, maintenance tasks. To show the feasibility of the proposed system, the system has been evaluated in a real context as a proof-of-concept.

4.1. Results of the Mapping System

First, given the current position of the robot (or team of robots), the maps and parcel masks are obtained. For our test, a GPS receiver with submeter precision was used. It is important to remark that the system must be inside the parcel to get the data accurately. From the initial position of the system, inside the parcel, the satellite maps of the parcel will be obtained using a satellite maps service via the Internet. In our case, two images were downloaded from the SIGPAC service, the photography of the parcel and the image with the boundaries of the parcel, as can be seen in Figure 3. Due to the characteristics of the latter image, some additional steps were included in Algorithm 3.

Figure 3.

Obtaining the satellite maps from the current position.

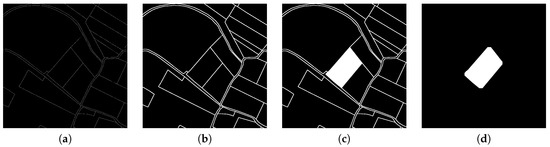

In Algorithm 3, the image with the borders of the parcel (see parcel image in Figure 3) is first processed to obtain a binary mask with pixels which belongs to the parcel and the pixels which are outside the parcel. For this reason, this image is first converted to black and white with a custom binarization algorithm (see Figure 4a). The purpose of the binarization is double: (1) to remove watermarks (red pixels in Figure 3) and (2) to highlight the borders (purple pixels in Figure 3).

Figure 4.

Filtering the parcel images to detect the parcel or grove where the robots are located. (a) after applying the custom binarization, (b) after dilating, (c) after filling the current parcel, (d) after erosion.

This early version of the binary mask is then dilated to perform a better connection between those pixels which correspond to the border (see Figure 4b). The dilation is performed three times with a 5 × 5 mask. Then, the pixel corresponding to the position of the robots is flood-filled in white (see Figure 4c). Finally, the image is eroded to revert the dilated filtering previously performed and to remove the borders between parcels. For this purpose, the erosion algorithm is run 6 times with the same 5 × 5 mask. After applying this last filter, the borders are removed and the parcel area is kept in the mask image. After obtaining the last binary mask, it is dilated again 3 times to better capture the real borders of the parcel (see Figure 4d).

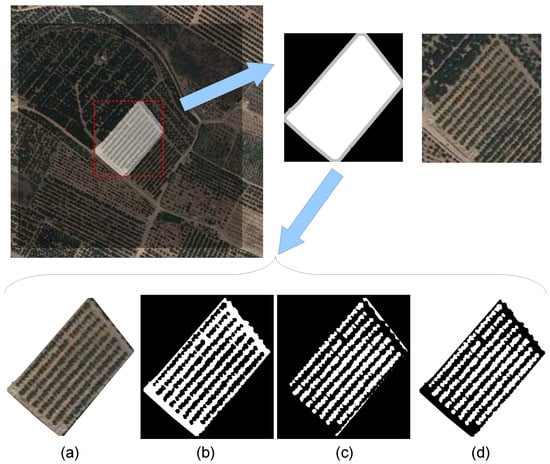

Then, it is only necessary to determine the bounding box surrounding the parcel in the parcel mask (see Figure 4d) to crop both images. This procedure is visually depicted on the top side of Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Generating binary maps from the satellite maps. (a) satellite view of the current parcel, (b) image of the current parcel, (c) image of the current parcel, (d) image of the current parcel.

4.2. Results of the Path Planner System

4.2.1. Detecting Tree Lines

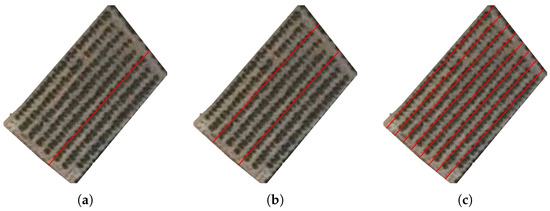

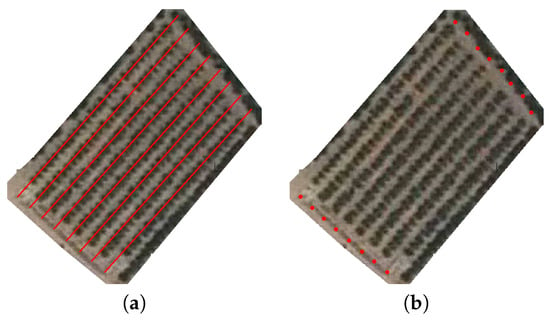

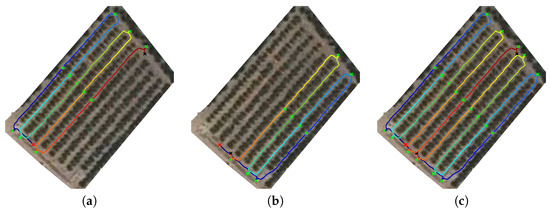

As a result of the Hough Transform application in Algorithm 7, all the orange tree rows are extracted as depicted in Figure 6. Although the order in which they are extracted does not correspond to the real order inside the grove, they are reordered and labelled according to its real order for further steps.

Figure 6.

Detecting tree rows with Hough. (a) current parcel view with the first detected row, (b) current parcel view with the first and second detected rows, (c) current parcel view with all detected rows.

4.2.2. Determining the Reference Points

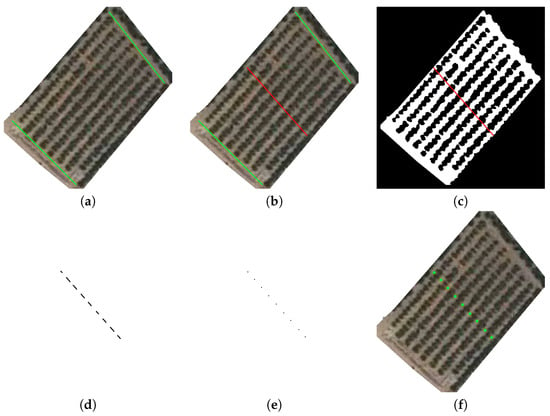

Algorithm 8 introduced how to determine the reference points that could be used as intermediate points in the path planner. Figure 7 and Figure 8 show a graphical example of these reference points. The former set of images shows how the tree row vertexes are computed, whereas the latter includes the process to extract the middle point of each path row.

Figure 7.

Detecting tree rows with Hough: (a) the extended satellite image related to the parcel with the detected lines and (b) the extended parcel with detected vertexes.

Figure 8.

Extracting reference points: (a) determining path row lines perpendicular to tree rows, (b) determining bisection between path row lines, (c,d) intersection between bisection and the Path binary map, and (e,f) new reference points and its representation on the parcel satellite image.

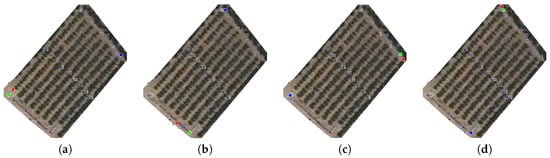

4.2.3. Determine Navigation Route from Reference Points

The results of Algorithm 9 are shown in Figure 9, where the numbered sequence of points is shown for four different initial configurations. In each one, the robot is placed near a different corner, simulating four possible initial places for the robots, so the four possible intermediate point distributions are considered.

Figure 9.

Intermediate points (numbered blue dots) for four different configurations depending on the robot initial position (red circle). The robot must move first to the closest corner (green circle), and then, it must navigate trough the intermediate points (small numbered circles) in order to achieve the last position in the opposite corner (big blue circle). (a) robot placed in the upper-left corner, (b) robot placed in the bottom-left corner, (c) robot placed in the bottom-right corner, (d) robot placed in the upper-right corner.

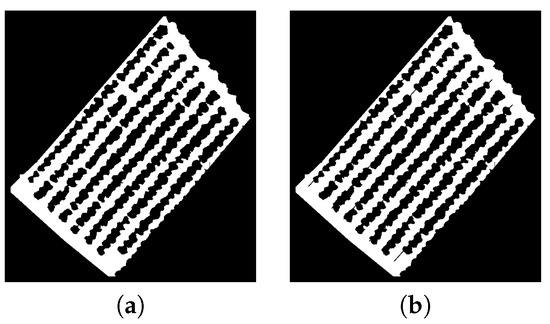

4.2.4. Path Planning Using Processed Satellite Imagery

Algorithm 11 is used to calculate the image required to determine the path that the robot should follow. Initially, the Path binary map (Figure 10a) was considered to be used as a base to determine the distances, but a modified version was used instead (Figure 10b). The modification consisted of adding the detected lines for the orange rows. The lines have been added to ensure that the robot navigates entirely through each path row and that there is no way of trespassing the orange tree rows during navigation.

Figure 10.

Generating images: (a) the original Path binary map and (b) the modified map.

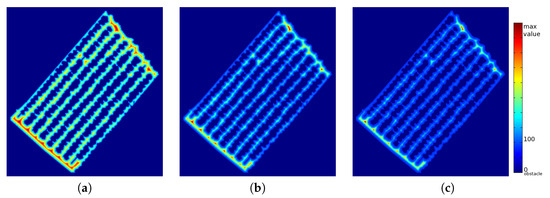

Three different images are shown in Figure 11a–c depending on the value of the parameter. After performing some experiments, the best results are obtained when the value is set to 3. With lower values of , the points close to obstacles were not penalized. With higher values, some narrow path rows were omitted from navigation due to their low-speed values. Finally, in our experiments, we used , as shown in Algorithm 11.

Figure 11.

Generating images: (a–c) graphical representations of values calculated with Equation (4) for equal to 1, 2, and 3.

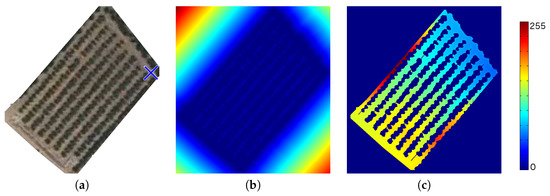

Figure 12a shows the parcel with the destination position drawn on it along with two representations of the matrix (Figure 12b,c). The first one corresponds to the normalized matrix of which the values are adapted to the range. However, it is nearly impossible to visually see how to arrive at the destination from any other point inside the parcel. It is due to the high penalty value assigned to those points belonging to obstacles (non-path points). For this reason, a modified way to visualize the distance matrix is introduced by the following equation:

Figure 12.

Distance images: (a) Parcel satellite image with the final position (blue x-cross), (b) a representation of the normalized matrix image, and (c) the modified representation.

In the image, it can be seen that there are high distance values in the first and last path rows (top-left and bottom-right sides of Figure 12c) which are not present in most of the other path rows. These two rows are narrow, and the speed values are, therefore, also quite low. For example, a robot placed in the top-left corner should navigate through the second path row to achieve the top-right corner instead of navigating through the shortest path (first path row). The aim of Fast Marching is to calculate the fastest path to achieving the destination point, not the shortest one. In the first row, the distance to obstacles is almost always very low.

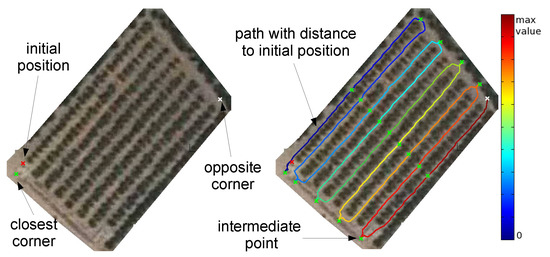

Figure 13 shows the results of the path planner for a robotic system. In the example image, the robotic is initially placed in the location marked with the red x-cross. Then, all the intermediate points, including the closest corner, are determined (green x-crosses).

Figure 13.

Example of a path planned for a robotic system.

Figure 14 introduces an example for a team composed of two robots. Figure 14a,b shows the complete determined path for the first and second robots. The first robot moves to the closest corner and then navigates through the grove, and the second robot moves to the closest opposite corner (located at the last row) and then also navigates through the grove but in the opposite direction (concerning the first robot). The path is coloured depending on the distance to the initial position (blue is used to denote low distances, and red is used to denote high distances).

Figure 14.

Determining path planning for a team composed by two robots (I). (a) path planning for robot, (b) path planning for robot, (c) real path for robot, (d) real path planning for robot, (e) superposition of (c) and (d).

However, the robotic systems will not perform all the paths because they will arrive at a point (stop point marked with a black x-cross) which has been already reached by the other robotic system and they will stop there (see Figure 14c,d). The colour between the initial point (red x-cross) and the stop point (black x-cross) graphically denotes the relative distance. Finally, Figure 14d shows a composition of the path done by each robotic system into one image.

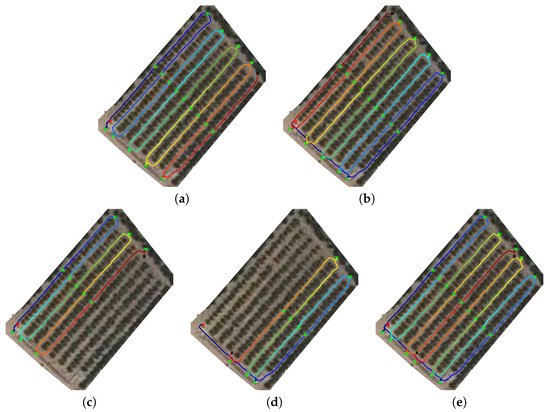

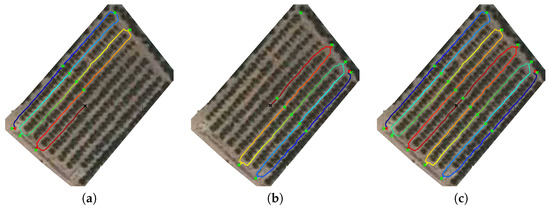

Similar examples are shown in Figure 15 and Figure 16, where the robots are not initially close to the corners. In the former example, the path between the initial position and the corners are not marked as “visited” because the robotic system navigation starts when the robot gets to the first intermediate point. In the latter case, we show an example where the robots stop when they detect that they have reached the same location.

Figure 15.

Determining path planning for a team composed by two robots (II). (a) real path for robot, (b) real path planning for robot, (c) superposition of (a) and (b).

Figure 16.

Determining path planning for a team composed by two robots (III). (a) real path for robot, (b) real path planning for robot, (c) superposition of (a) and (b).

5. Conclusions

This paper has shown a proof-of-concept of a novel path planning based on remote imagery publicly available. The partial results, shown as intermediate illustrative real examples of each performed step, encourage reliance on satellite imagery and cadastral information to automatically generate the path planning. According to it, useful knowledge can be obtained from the combination of satellite imagery and information about the borders that divide the land into parcels. Some limitations have been also identified: some parameters (such as thresholds) are image dependent and have been manually set for the current set of satellite images; it can only be applied in the current configuration of citric trees in rows; and changes in the grove distribution are not immediately reflected in the satellite imagery. In our platform, this path planning is complemented by local imagery, which provides navigation centred in the path.

We can conclude by remarking that the steps necessary to autonomously determine path planning in citric groves in the province of Castellón have been described in this paper and that the potential of this autonomous path planner has been shown with successful use cases. Firstly, a procedure to extract binary maps from a public remote imagery service has been described. Secondly, a novel methodology to automatically detect reference points from orange groves has been introduced using remote imagery. Some knowledge and global information about the grove can be extracted from those points. Thirdly, a procedure to determine a path has been designed for a stand-alone robotic vehicle. Moreover, it has been modified to be suitable for a team composed of two robotic systems. The first path planning provides useful information, and it may be considered the fast way to perform a maintenance task. This path is complemented by local navigation techniques (see Reference [21]) to obtain optimal results in the final implementation of the whole navigation module. Finally, although we introduced the system for orange groves, all the steps can be applied to other groves with a similar main structure (other citrus groves or some olive groves). Moreover, they could be also adapted for other crops or situations by changing the way they extract reference points, i.e., a hybrid team of multiple robots will require a specific planner and path strategy.

Finally, this paper has introduced a proof-of-concept showing the feasibility of the proposed algorithms to automatically determine path planning inside a citric grove. The proposed algorithms can be used to ease the manual labelling of satellite imagery to create manual maps for each parcel. We will identify the full implementation in different contexts and experimental validation as further work.

Author Contributions

J.T.-S. and P.N. equally contributed in the elaboration of this work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Blazquez, C.H.; Edwards, G.J.; Horn, F.W. Citrus grove mapping with colored infrared aerial photography. Proc. Fla. State Hortic. Soc. 1979, 91, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- López-Granados, F. Weed detection for site-specific weed management: Mapping and real-time approaches. Weed Res. 2011, 51, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorós López, J.; Izquierdo Verdiguier, E.; Gómez Chova, L.; Muñoz Marí, J.; Rodríguez Barreiro, J.; Camps Valls, G.; Calpe Maravilla, J. Land cover classification of VHR airborne images for citrus grove identification. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2011, 66, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.; Wolford, S. Fresh-market quality tree fruit harvester. Part II: Apples. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2003, 19, 545–548. [Google Scholar]

- Arima, S.; Kondo, N.; Monta, M. Strawberry Harvesting Robot on Table-Top Culture; Technical Report; American Society of Association Executives (ASAE): St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hannan, M.; Burks, T. Current Developments in Automated Citrus Harvesting; Technical Report; American Society of Association Executives (ASAE): St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Foglia, M.; Reina, G. Agricultural Robot Radicchio Harvesting. J. Field Robot. 2006, 23, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, J.; Aleixos, N.; Roger, J.; Rabatel, G.; Moltó, E. Robotic weed control using machine vision. Biosyst. Eng. 2002, 83, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, T.; Jakobsen, H. Agricultural robotic platform with four wheel steering for weed detection. Biosyst. Eng. 2004, 87, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, D.; Giles, D.; Slaughter, D. Weeds accurately mapped using DGPS and ground-based vision identification. Calif. Agric. 2004, 58, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, D.; Downey, D.; Slaughter, D.; Brevis-Acuna, J.; Lanini, W. Herbicide micro-dosing for weed control in field grown processing tomatoes. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2004, 20, 7355–7743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Tian, L. Development of a low-cost agricultural remote sensing system based on an autonomous unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). Biosyst. Eng. 2011, 108, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalponte, M.; Bruzzone, L.; Gianelle, D. Tree species classification in the Southern Alps based on the fusion of very high geometrical resolution multispectral/hyperspectral images and LiDAR data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 123, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stentz, A.; Dima, C.; Wellington, C.; Herman, H.; Stager, D. A System for Semi-Autonomous Tractor Operations. Auton. Robot. 2002, 13, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, V.; Burks, T.F.; Dixon, W.E. Sensor fusion using fuzzy logic enhanced kalman filter for autonomous vehicle guidance in citrus groves. Trans. ASABE 2009, 52, 1411–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, A.L.; Huertas, A.; Matthies, L.H. Stereo-vision-based terrain mapping for off-road autonomous navigation. Proc. SPIE 2009, 7332, 733210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, T.; van Asselt, K.; Bontsema, J.; Müller, J.; van Straten, G. Autonomous navigation using a robot platform in a sugar beet field. Biosyst. Eng. 2011, 109, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velagic, J.; Osmic, N.; Hodzic, F.; Siljak, H. Outdoor navigation of a mobile robot using GPS and GPRS communication system. In Proceedings of the ELMAR-2011, Zadar, Croatia, 14–16 September 2011; pp. 173–177. [Google Scholar]

- Rovira-Más, F. Global-referenced navigation grids for off-road vehicles and environments. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2012, 60, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Zhang, L.; Grift, T.E. Variable field-of-view machine vision based row guidance of an agricultural robot. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2012, 84, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sospedra, J.; Nebot, P. A New Approach to Visual-Based Sensory System for Navigation into Orange Groves. Sensors 2011, 11, 4086–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sospedra, J.; Nebot, P. Two-stage procedure based on smoothed ensembles of neural networks applied to weed detection in orange groves. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 123, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebot, P.; Torres-Sospedra, J.; Martinez, R.J. A New HLA-Based Distributed Control Architecture for Agricultural Teams of Robots in Hybrid Applications with Real and Simulated Devices or Environments. Sensors 2011, 11, 4385–4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hough, P. Method and Means for Recognizing Complex Patterns. U.S. Patent US3069654A, 18 December 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Rovira-Más, F.; Zhang, Q.; Reid, J.F.; Will, J.D. Hough-transform-based vision algorithm for crop row detection of an automated agricultural vehicle. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2005, 219, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Tan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, S. Walking Goal Line Detection Based on Machine Vision on Harvesting Robot. In Proceedings of the 2011 Third Pacific-Asia Conference on Circuits, Communications and System (PACCS), Wuhan, China, 17–18 July 2011; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, L.; Recio, J.; Fernández-Sarría, A.; Hermosilla, T. A feature extraction software tool for agricultural object-based image analysis. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2011, 76, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Hegarat-Mascle, S.; Ottle, C. Automatic detection of field furrows from very high resolution optical imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2013, 34, 3467–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchior, P.; Orsoni, B.; Lavialle, O.; Poty, A.; Oustaloup, A. Consideration of obstacle danger level in path planning using A* and Fast-Marching optimisation: Comparative study. Signal Process. 2003, 83, 2387–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, S.; Moreno, L.; Abderrahim, M.; Martin, F. Path Planning for Mobile Robot Navigation using Voronoi Diagram and Fast Marching. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Beijing, China, 9–15 October 2006; pp. 2376–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, S.; Moreno, L.; Lima, P.U. Robot formation motion planning using Fast Marching. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2011, 59, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, S.; Malfaz, M.; Blanco, D. Application of the fast marching method for outdoor motion planning in robotics. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2013, 61, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardiyanto, I.; Miura, J. Real-time navigation using randomized kinodynamic planning with arrival time field. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2012, 60, 1579–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassouna, M.; Farag, A. MultiStencils Fast Marching Methods: A Highly Accurate Solution to the Eikonal Equation on Cartesian Domains. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2007, 29, 1563–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).