A Faster Algorithm for Reducing the Computational Complexity of Convolutional Neural Networks

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Related Work

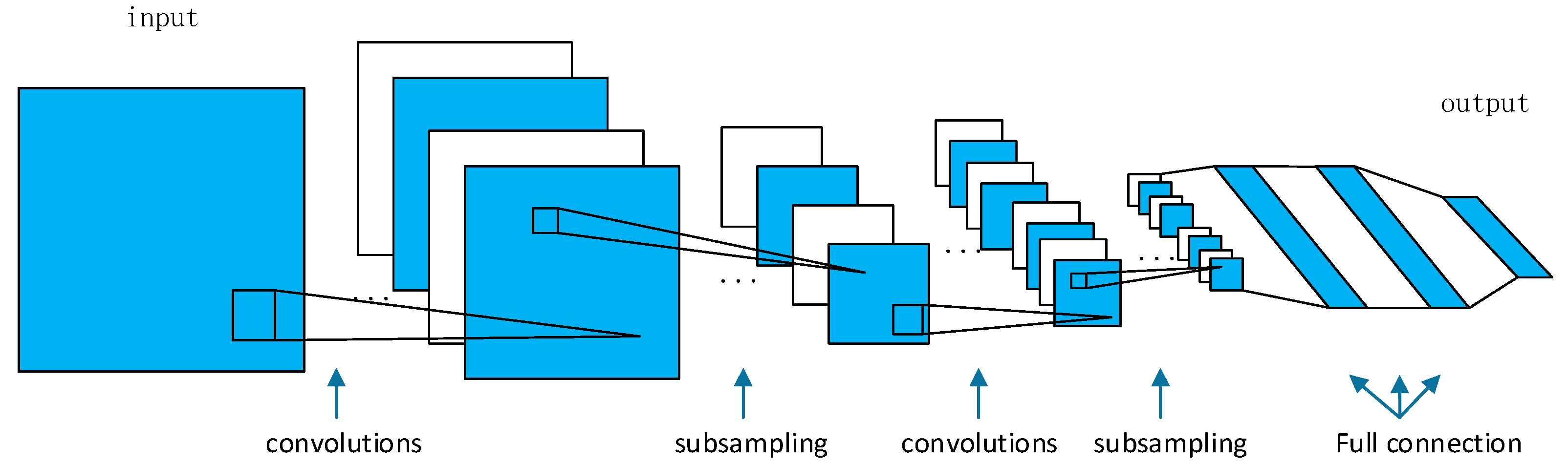

2.1. Convolutional Neural Networks

2.2. Winograd Algorithm

2.3. Strassen Algorithm

3. Proposed Algorithm

| Algorithm 1. Implementation of the Winograd algorithm. |

| 1 for r = 1 to the number of output maps 2 for q = 1 to the number of input maps 3 U = GwGT 4 end 5 end 6 for p = 1 to batch size 7 for q = 1 to the number of input maps 8 for k = 1 to the number of image tiles 9 V = BTxB 10 end 11 end 12 end 13 for p = 1 to batch size 14 for r = 1 to the number of output maps 15 for j = 1 to the number of image tiles 16 M = zero; 17 for q = 1 to the number of input maps 18 M = M + AT(UV)A 19 end 20 end 21 end 22 end |

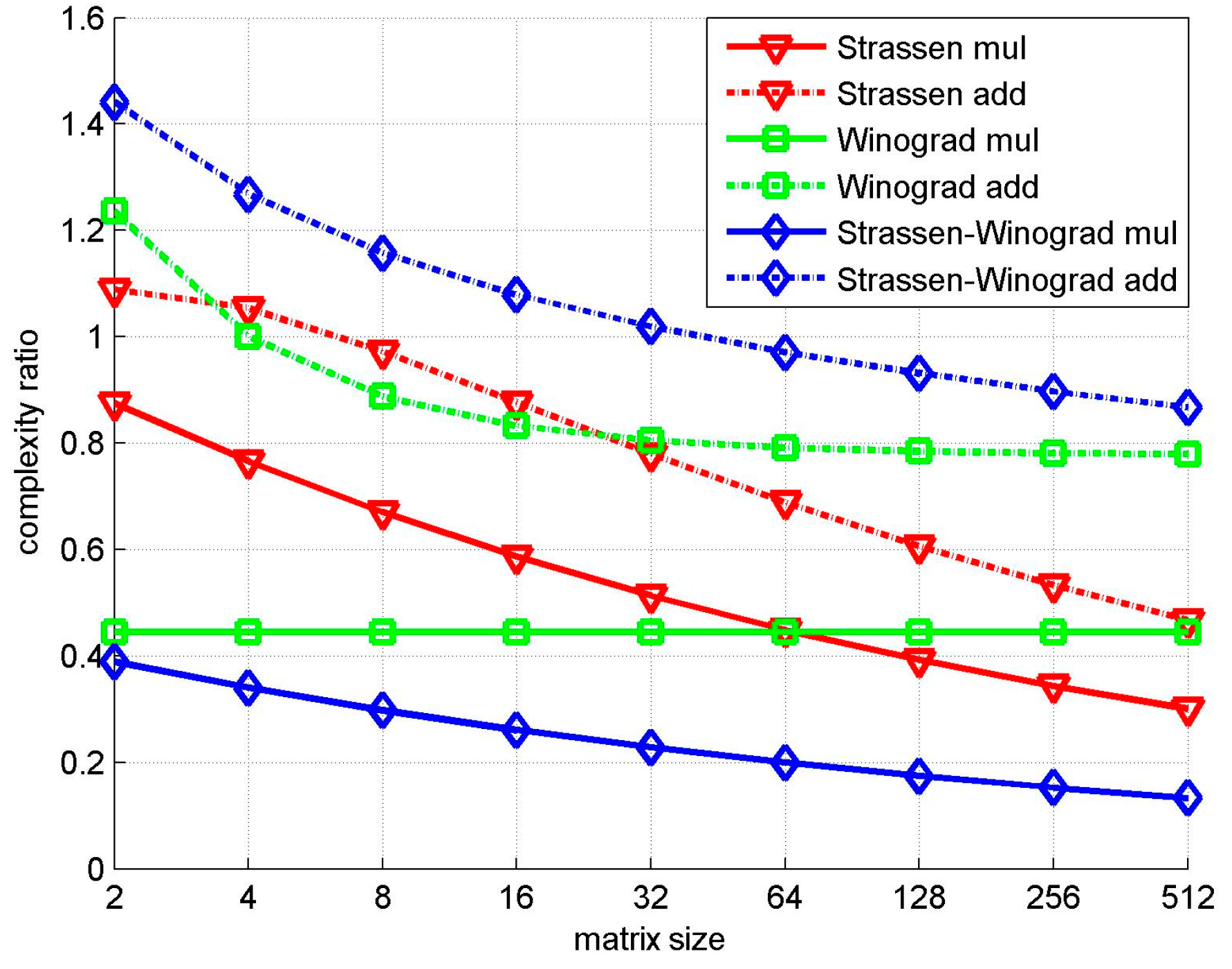

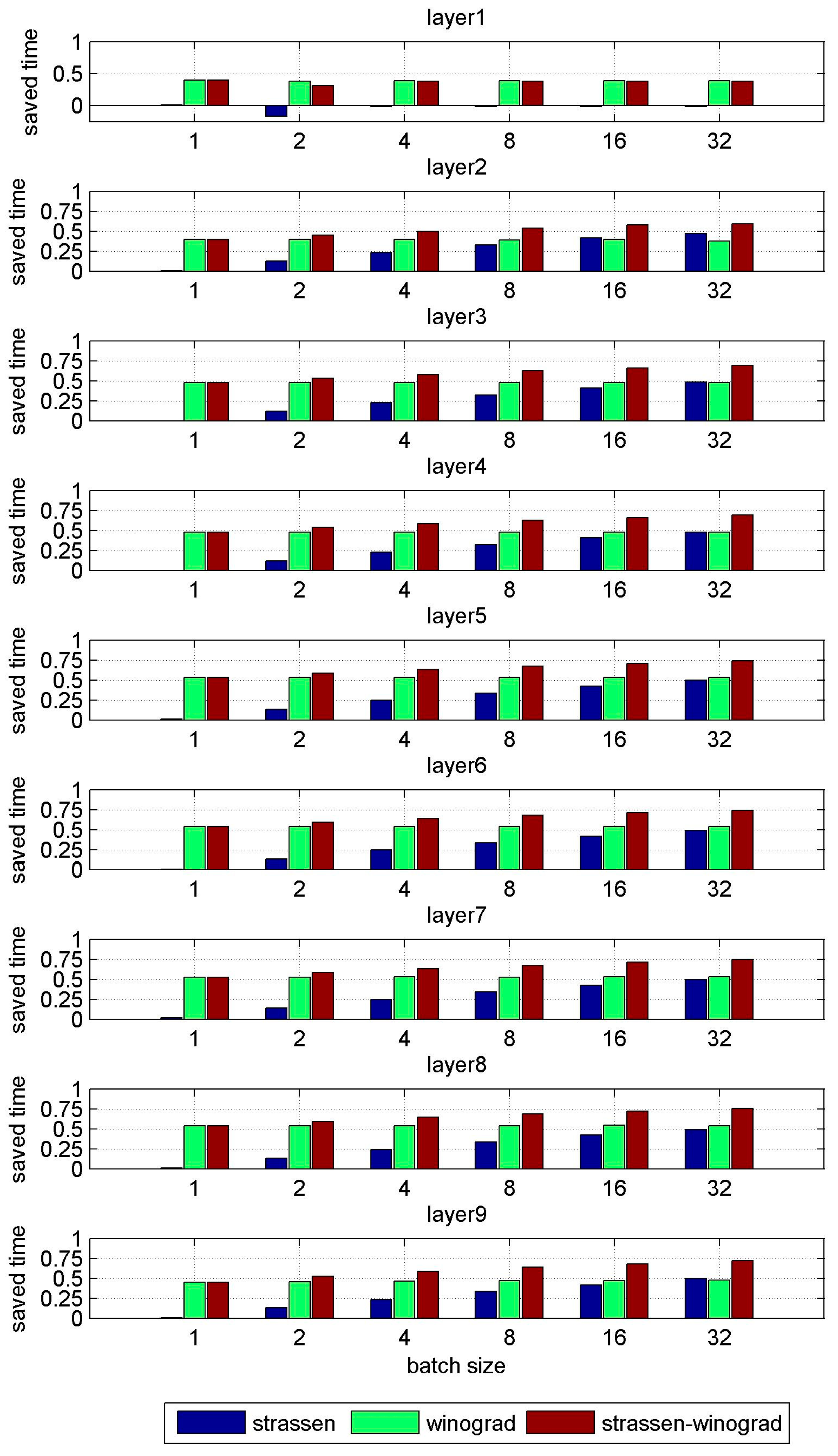

4. Simulation Results

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv, 2014; arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.; Wan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, T.; Huo, H.; Fang, T. Exploiting Convolutional Neural Networks with Deeply Local Description for Remote Sensing Image Classification. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 11215–11228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 3–6 December 2012; Volume 60, pp. 1097–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Le, N.M.; Granger, E.; Kiran, M. A comparison of CNN-based face and head detectors for real-time video surveillance applications. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Image Processing Theory, Tools and Applications, Montreal, QC, Canada, 28 November–1 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014; pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Denil, M.; Shakibi, B.; Dinh, L. Predicting Parameters in Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 5–10 December 2013; pp. 2148–2156. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Pool, J.; Tran, J. Learning both Weights and Connections for Efficient Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Istanbul, Turkey, 9–12 November 2015; pp. 1135–1143. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Yao, A.; Chen, Y. Dynamic Network Surgery for Efficient DNNs. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 1379–1387. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J.; Wang, J.; Yao, S. Going Deeper with Embedded FPGA Platform for Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the ACM/SIGDA International Symposium on Field-Programmable Gate Arrays, Monterey, CA, USA, 21–23 February 2016; pp. 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Courbariaux, M.; Bengio, Y.; David, J.P. Low Precision Arithmetic for Deep Learning. arXiv, 2014; arXiv:1412.0724. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Agrawal, A.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Narayanan, P. Deep Learning with Limited Numerical Precision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Lille, France, 7–9 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rastegari, M.; Ordonez, V.; Redmon, J. XNOR-Net: ImageNet Classification Using Binary Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 525–542. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Han, S.; Mao, H. Trained Ternary Quantization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Toulon, France, 24–26 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zou, J.; Ming, X.; Sun, J. Efficient and accurate approximations of nonlinear convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2014; pp. 1984–1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu, M.; Henaff, M.; Lecun, Y.; Chintala, S.; Piantino, S.; Lecun, Y. Fast Training of Convolutional Networks through FFTs. arXiv, 2013; arXiv:1312.5851. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilache, N.; Johnson, J.; Mathieu, M. Fast Convolutional Nets with fbfft: A GPU Performance Evaluation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Toom, A.L. The complexity of a scheme of functional elements simulating the multiplication of integers. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1963, 150, 496–498. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, S.A. On the Minimum Computation Time for Multiplication. Ph.D. Thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Winograd, S. Arithmetic Complexity of Computations; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Jin, J.; Wang, X. A novel multilayer correlation maximization model for improving CCA-based frequency recognition in SSVEP brain-computer interface. Int. J. Neural Syst. 2018, 28, 1750039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L. An adaptive neural network approach for operator functional state prediction using psychophysiological data. Integr. Comput. Aided Eng. 2015, 23, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavin, A.; Gray, S. Fast Algorithms for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Caesars Palace, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 4013–4021. [Google Scholar]

- Strassen, V. Gaussian elimination is not optimal. Numer. Math. 1969, 13, 354–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, J.; Xiao, B. Minimizing Computation in Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning—ICANN 2014, Hamburg, Germany, 15–19 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Matrix Size | Conventional | Strassen | Winograd | Strassen-Winograd | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mul | Add | Mul | Add | Mul | Add | Mul | Add |

| 2 | 294,912 | 278,528 | 258,048 | 303,104 | 131,072 | 344,176 | 114,688 | 401,520 |

| 4 | 2,359,296 | 2,293,760 | 1,806,336 | 2,416,640 | 1,048,576 | 2,294,208 | 802,816 | 2,908,608 |

| 8 | 1.89 × 107 | 1.86 × 107 | 1.26 × 107 | 1.81 × 107 | 8.39 × 106 | 1.65 × 107 | 5.62 × 106 | 2.15 × 107 |

| 16 | 1.51 × 108 | 1.50 × 108 | 8.85 × 107 | 1.31 × 108 | 6.71 × 107 | 1.25 × 108 | 3.93 × 107 | 1.62 × 108 |

| 32 | 1.21 × 109 | 1.20 × 109 | 6.20 × 108 | 9.39 × 108 | 5.37 × 108 | 9.69 × 108 | 2.75 × 108 | 1.23 × 109 |

| 64 | 9.66 × 109 | 9.65 × 109 | 4.34 × 109 | 6.65 × 109 | 4.29 × 109 | 7.63 × 109 | 1.93 × 109 | 9.37 × 109 |

| 128 | 7.73 × 1010 | 7.72 × 1010 | 3.04 × 1010 | 4.68 × 1010 | 3.44 × 1010 | 6.06 × 1010 | 1.35 × 1010 | 7.19 × 1010 |

| 256 | 6.18 × 1011 | 6.18 × 1011 | 2.13 × 1011 | 3.29 × 1011 | 2.75 × 1011 | 4.83 × 1011 | 9.45 × 1010 | 5.55 × 1011 |

| 512 | 4.95 × 1012 | 4.95 × 1012 | 1.49 × 1012 | 2.31 × 1012 | 2.20 × 1012 | 3.86 × 1012 | 6.61 × 1011 | 4.29 × 1012 |

| Convolutional Layer | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Depth | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Q | 3 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 256 | 256 | 512 | 512 | |

| R | 64 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 256 | 256 | 512 | 512 | 512 | |

| Mw(Nw) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| My(Ny) | 224 | 224 | 112 | 112 | 56 | 56 | 28 | 28 | 14 | |

| Layer | Batch Size | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Layer1 | Conventional | 24s | 48s | 94s | 187s | 375s | 752s |

| Strassen | 24s | 56s | 95s | 191s | 383s | 768s | |

| Winograd | 14s | 29s | 57s | 115s | 230s | 462s | |

| Strassen-Winograd | 14s | 33s | 58s | 117s | 234s | 470s | |

| Layer2 | Conventional | 493s | 986s | 1971s | 3939s | 7888s | 15821s |

| Strassen | 492s | 861s | 1508s | 2636s | 4625s | 8438s | |

| Winograd | 299s | 598s | 1196s | 2396s | 4787s | 9935s | |

| Strassen-Winograd | 299s | 543s | 992s | 1818s | 3348s | 6468s | |

| Layer3 | Conventional | 245s | 490s | 980s | 1962s | 3916s | 7858s |

| Strassen | 247s | 433s | 759s | 1328s | 2325s | 4076s | |

| Winograd | 128s | 256s | 513s | 1025s | 2049s | 4102s | |

| Strassen-Winograd | 128s | 229s | 411s | 737s | 1335s | 2417s | |

| Layer4 | Conventional | 488s | 978s | 1954s | 3908s | 7819s | 15639s |

| Strassen | 494s | 864s | 1513s | 2648s | 4626s | 8140s | |

| Winograd | 254s | 509s | 1017s | 2033s | 4075s | 8168s | |

| Strassen-Winograd | 254s | 455s | 814s | 1466s | 2645s | 4811s | |

| Layer5 | Conventional | 250s | 502s | 1007s | 2004s | 4012s | 8076s |

| Strassen | 248s | 436s | 761s | 1328s | 2317s | 4078s | |

| Winograd | 118s | 236s | 471s | 942s | 1881s | 3776s | |

| Strassen-Winograd | 118s | 209s | 370s | 656s | 1167s | 2085s | |

| Layer6 | Conventional | 498s | 1001s | 1998s | 3995s | 7948s | 15892s |

| Strassen | 494s | 868s | 1507s | 2646s | 4643s | 8102s | |

| Winograd | 231s | 462s | 923s | 1844s | 3693s | 7382s | |

| Strassen-Winograd | 231s | 410s | 725s | 1286s | 2296s | 4089s | |

| Layer7 | Conventional | 244s | 487s | 980s | 1940s | 3910s | 7820s |

| Strassen | 241s | 421s | 739s | 1283s | 2250s | 3961s | |

| Winograd | 116s | 231s | 461s | 920s | 1839s | 3680s | |

| Strassen-Winograd | 116s | 204s | 358s | 630s | 1111s | 1961s | |

| Layer8 | Conventional | 479s | 955s | 1917s | 3833s | 7675s | 15319s |

| Strassen | 474s | 829s | 1453s | 2546s | 4447s | 7811s | |

| Winograd | 222s | 443s | 884s | 1766s | 3524s | 7068s | |

| Strassen-Winograd | 223s | 391s | 686s | 1210s | 2129s | 3772s | |

| Layer9 | Conventional | 118s | 237s | 474s | 951s | 1900s | 3823s |

| Strassen | 117s | 206s | 362s | 631s | 1107s | 1937s | |

| Winograd | 65s | 128s | 254s | 507s | 1009s | 2010s | |

| Strassen-Winograd | 65s | 113s | 197s | 345s | 606s | 1063s |

| Conventional | Strassen | Winograd | Strassen-Winograd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Layer1 | 1.25 × 10−6 | 3.03 × 10−6 | 2.68 × 10−6 | 4.01 × 10−6 |

| Layer2 | 2.46 × 10−5 | 7.59 × 10−5 | 4.62 × 10−5 | 9.50 × 10−5 |

| Layer3 | 2.65 × 10−5 | 7.23 × 10−5 | 4.83 × 10−5 | 9.51 × 10−5 |

| Layer4 | 4.94 × 10−5 | 1.50 × 10−4 | 9.40 × 10−5 | 1.78 × 10−4 |

| Layer5 | 5.14 × 10−5 | 1.46 × 10−4 | 1.00 × 10−4 | 1.74 × 10−4 |

| Layer6 | 9.80 × 10−5 | 2.94 × 10−4 | 1.88 × 10−4 | 3.50 × 10−4 |

| Layer7 | 9.92 × 10−5 | 2.82 × 10−4 | 1.79 × 10−4 | 3.39 × 10−4 |

| Layer8 | 2.09 × 10−4 | 5.89 × 10−4 | 3.51 × 10−4 | 6.99 × 10−4 |

| Layer9 | 1.84 × 10−4 | 5.76 × 10−4 | 3.50 × 10−4 | 6.16 × 10−4 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, L.; Liu, P. A Faster Algorithm for Reducing the Computational Complexity of Convolutional Neural Networks. Algorithms 2018, 11, 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/a11100159

Zhao Y, Wang D, Wang L, Liu P. A Faster Algorithm for Reducing the Computational Complexity of Convolutional Neural Networks. Algorithms. 2018; 11(10):159. https://doi.org/10.3390/a11100159

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Yulin, Donghui Wang, Leiou Wang, and Peng Liu. 2018. "A Faster Algorithm for Reducing the Computational Complexity of Convolutional Neural Networks" Algorithms 11, no. 10: 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/a11100159

APA StyleZhao, Y., Wang, D., Wang, L., & Liu, P. (2018). A Faster Algorithm for Reducing the Computational Complexity of Convolutional Neural Networks. Algorithms, 11(10), 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/a11100159