Abstract

An algorithm is presented for the simulation of two partially flexible macromolecules where the interaction between the flexible parts and rigid parts is represented by energy grids associated with the rigid part of each macromolecule. The proposed algorithm avoids the transformation of the grid upon molecular movement at the expense of the significantly lesser effect of transforming the flexible part.

1. Introduction

Atomic level simulation of macromolecules is currently performed almost exclusively by molecular dynamics. Its success, due to it following the actual time course of the system, is also the source of its ultimate limitation—that of the time scale reachable by it. However, it was argued earlier that Monte Carlo, the preferred technique at the early times of molecular simulations, has the potential of overcome this limitation as it is not bound to time [1]. In spite of this potential, there are few groups working along this line [2,3,4]. A further advantage of the Monte Carlo approach over molecular dynamics is the ease of limiting the sampling to certain parts of the system and/or to a limited set of degrees of freedom.

Representing the field of rigid macromolecules on grids specific to the type of the interacting atoms is a standard technique employed in many docking softwares [5,6] where the target is held rigid and a flexible ligand is moved around the target. Assuming that there are NR atoms in the rigid part, in the energy calculation for each moving atom, the grid representation of the rigid part of the macromolecule replaces the calculation of NR distances with the calculation of the distances from the eight nearest gridpoints followed by interpolating the corresponding eight energy terms adding an effort equivalent to about two more distance calculations. Since the most likely macromolecule type to be thus modeled is a protein and protein domains have well over a thousand atoms (i.e., NR ≃ 1000 is a low estimate in most cases), using the grid representation saves a factor of NR/10, that is, likely a factor of ~100 or more. This idea has also been combined with the Monte Carlo approach for the simulation of protein loops [7] where only a small part of the molecule is moved during the simulation, achieving similar speedup. The fact that the rigid part of the macromolecule is also kept in place was an important aspect for the success of these applications since it allowed keeping the grid(s) unchanged during the entire simulation. The algorithm described here is designed to maintain the gains achievable by the use of the grids for the case when a macromolecule is moved.

When modeling the interaction of two partially rigid macromolecules, the straightforward extension of these algorithms would run into the difficulty of having to move at least one of the sets of grids. This introduces additional computation expenses: (a) finding the nearest eight gridpoints would be more involved since the rotated grids would not be aligned with the Cartesian axes and (b) the additional computational burden of transforming Nt * Ng3 grid values (with Nt being the number of grid types and Ng the number of gridpoints along one Cartesian direction) whenever a whole macromolecule is moved. The proposed algorithm would eliminate these problems at negligible added computational cost.

2. The Algorithm Proposed

This note describes an algorithm that allows the movement of the rigid part while maintaining the grids in their original positions, giving rise to the same savings as obtained for the single molecule system.

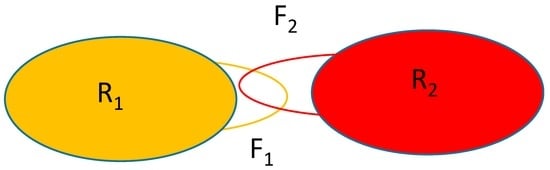

Figure 1 shows the schematics of the system considered. The rigid parts of the macromolecules are represented by the oblongs labeled with R1 and R2 and the flexible parts are represented by the loops F1 and F2. Macromolecule 2 will be held in place with only the F2 part moving while macromolecule 1 is allowed to translate/rotate whilst also changing the conformation of the part represented by the atoms forming F1.

Figure 1.

Schematics of the system considered. R1, R2: rigid part of macromolecules 1 and 2, respectively; F1, F2: flexible part of macromolecules 1 and 2, respectively.

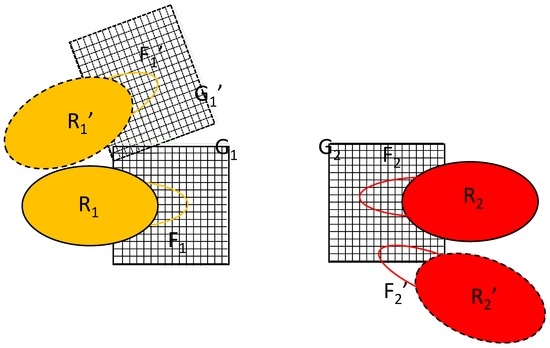

The key to the algorithm proposed is the simultaneous updating of two equivalent copies of the flexible parts, labeled F1′ and F2′ in Figure 2. The difference between the primed and unprimed versions is just a translation/rotation of the rigid part; their conformations are identical. The initial position of macromolecule 1 is R1 and its position after rigid translation/rotation is R1′. Such a transformation would also require the transformation of grid G1 into G1′, as shown in Figure 2, but the proposed algorithm avoids this. Instead, the algorithm introduces the alternative position of macromolecule 2, R2′. It is constructed by translating/rotating the whole complex in such a way that the rigid part of macromolecule 1 is overlaid on its initial position/orientation. Note that, in reality, only the coordinates of the flexible part F2 are involved in the calculation.

Figure 2.

Schematics of the copies needed for the proposed algorithm. R1, R2: rigid part of macromolecules 1 and 2, respectively; F1, F2: flexible part of macromolecules 1 and 2, respectively; G1, G2: The set of grids representing the field of the rigid parts R1 and R2, respectively; Primed items represent the systems after change from the initial position, orientation and conformation. The two interacting systems are shown with their distance increased for clarity.

Since E(F1′,G1′) = E(F1,G1) and E(F2,G1′) = E(F2′,G1) where E(F,G) represents the energy of flexible part F interacting with grid G, this arrangement allows the calculation of the energy of a new complex as follows:

where E(F1′,F2) is the energy of the interaction between flexible parts F1′ and F2.

E = E(F1,G1) + E(F2,G2) + E(F1′,G2) + E(F2′,G1) + E(F1′,F2)

Two kinds of changes are considered: translate/rotate macromolecule 1 in the current conformation of its flexible part, F1, or change the conformation of the flexible part of one of the macromolecules, F1 or F2. When macromolecule 1 is translated/rotated, the coordinates of F1′ and F2′ have to be updated. When the flexible part of macromolecule 1 is changed, the coordinates of F1 and F1′ have to be updated. When the flexible part of macromolecule 2 is changed, the coordinates of F2 and F2′ have to be updated.

Note that in Equation (1), the energy of the interaction between the two rigid parts, being separated by the layers of the flexible part, is assumed to be negligible. For the Van der Waals interactions, this assumption holds to a good approximation. As for the electrostatic interactions, it is possible to include them, at negligible computational expense, using a multipole representation of the charge distribution since the two rigid parts can be enclosed into nonoverlapping spheres, ensuring the validity of the multipole representation.

3. Discussion

This note presented an algorithm that extends the use of grid-based force fields to the modeling of two partially flexible macromolecules by eliminating the added computation involved in determining the nearest gridpoints, and the computation to transform the grids. As for the determination of the nearest gridpoints, the proposed algorithm’s use of a transformed copy is adding a similar computational expense, so there is no net effect. The main saving is achieved by eliminating the transformation of the grids.

Assuming that there are 10 different grids corresponding to different atom types, the proposed algorithm would save the transformation of ~10 × Ng3 points at the negligible expense of transforming the additional NF atoms of the flexible part. Assuming that Ng ≃ 200 (a reasonable value in our experience) and that the flexible part is about 10% of the whole molecule, about ~8 × 105 transformations can be eliminated at the negligible expense of ~2 × 102 additional transformations of the flexible part. The estimate of the overall effect is less straightforward. It is reasonable to assume that the volume of the grid is proportional to the volume of the flexible atoms or, equivalently, that the number of grids along an axis is proportional to the cube root of the number of flexible atoms, i.e., Ng = c1 × NF1/3, and that the overall energy calculation will be dominated by the direct interactions of the flexible parts. Assuming further, as is generally true for Markov-chain Monte Carlo, that a move involves a small limited fraction of the atoms available for moving, the work in calculating the energy change is c2 × NF. This means that the ratio of the work involved in the energy calculation per step and the corresponding savings by using the algorithm proposed here is [c2 × (NF)]/[W × 10 × (c1 × NF1/3)3] = c2/(10 × W × c13) where W is the fraction of the time during which the whole molecule is moved. Thus, in the limit of a large number of flexible atoms, the expense of transforming the grid is commensurable to the rest of the energy calculation, thus the upper limit of the savings is a constant, depending, among others, on the frequency of whole molecule moves. Likely applications, however, are far from this limit: assuming (a relatively large) NF ≃ 100 and Ng ≃ 200 and the number of changed flexible atoms ~50 (an overestimate), the ratio of the energy calculation to the grid transformation calculation would be (50 × 100)/(W × 10 × 2003) = 10 −4(5/(W × 8) × F where F is the ratio of the computation expenses of calculating a distance and transforming a coordinate. Clearly, it shows a significant gain for systems of systems of likely size.

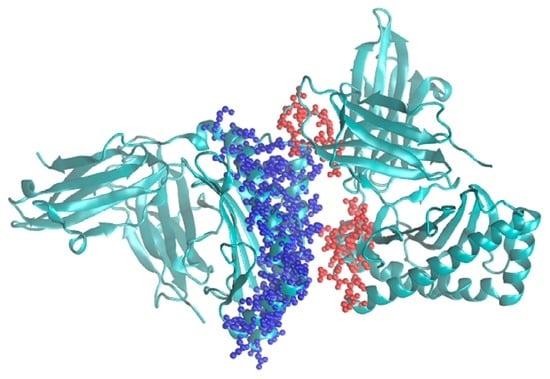

Thus, it is expected that this algorithm would significantly speed up the modeling of protein complexes where the interaction region is relatively small compared to the overall volume of the complex and foster further developments in the Monte Carlo methodology. It is planned to implement it into the program called MMC [4] that already includes the single grid version. A typical example for its use would be modeling major histocompatibility complexes (MHC) [8]. An example for such a system is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Crystal structure of MHC class I HLA-A2.1 bound to a photocleavable peptide (PDB ID: 2X70). The possible choices of flexible parts corresponding to F1 and F2 are shown in red and blue spheres, respectively.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part through the computational resources and staff expertise provided by the Department of Scientific Computing at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Mezei, M. On the potential of Monte Carlo methods for simulating macromolecular assemblies. In Third International Workshop for Methods for Macromolecular Modeling Conference Proceedings; Gan, H.H., Schlick, T., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Tirado-Rives, J. Molecular modeling of organic and biomolecular systems using BOSS and MCPRO. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1689–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullmann, R.T.; Ullmann, G.M. GMCT: A Monte Carlo simulation package for macromolecular receptors. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezei, M. MMC: Monte Carlo Program for Molecular Assemblies. Available online: http://inka.mssm.edu/~mezei/mmc (accessed on 27 December 2016).

- Goodford, P.J. A computational procedure for determining energetically favorable binding sites on biologically important macromolecules. J. Med. Chem. 1985, 28, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.-Y.; Zhang, H.-X.; Mezei, M.; Cui, M. Molecular docking: A powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery. Curr. Comput. Aided Drug Des. 2011, 7, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, M.; Mezei, M.; Osman, R. Prediction of protein loop structures using a local move Monte Carlo approach and a grid-based force field. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2008, 21, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janeway, C.A., Jr.; Travers, P.; Mark, W.; Mark, J.S. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease, 5th ed.; Garland Science: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).