LCA of 1,4-Butanediol Produced via Direct Fermentation of Sugars from Wheat Straw Feedstock within a Territorial Biorefinery

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

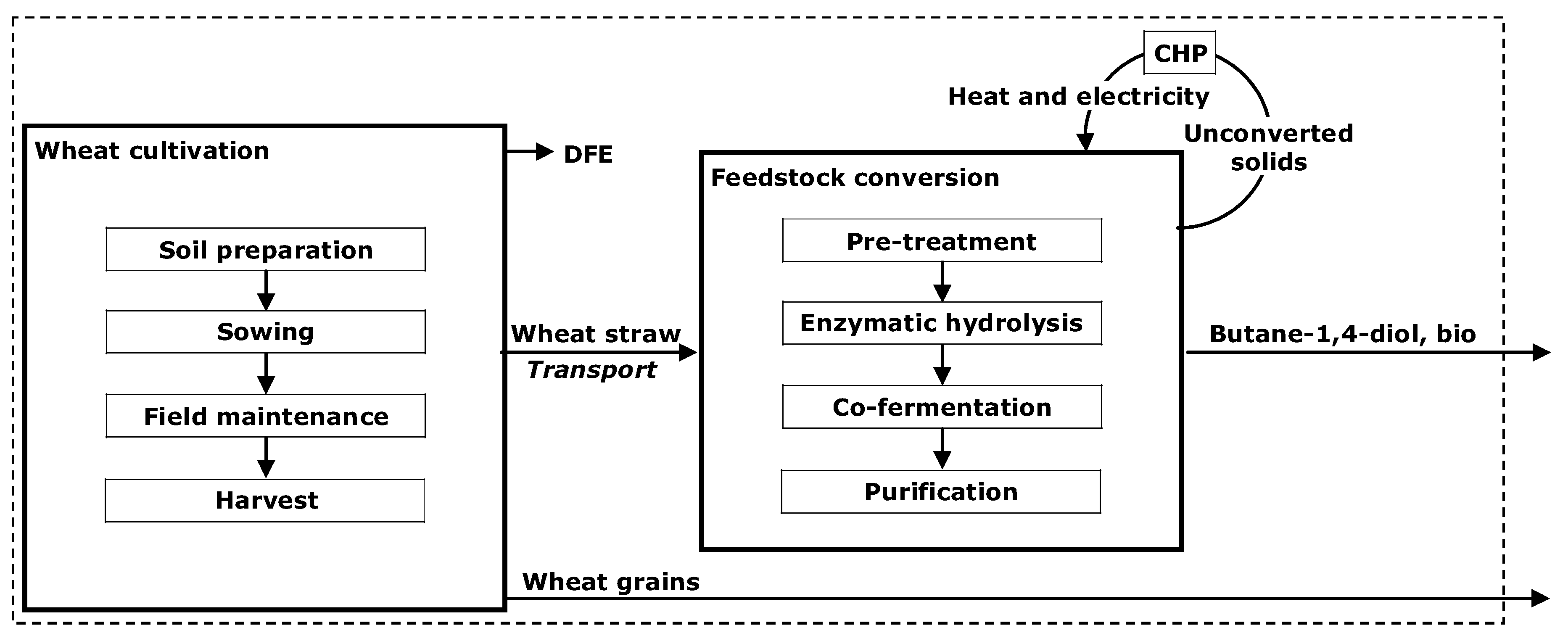

2.1. Goal and Scope

2.2. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

2.2.1. LignocellulosicFeedstock Cultivation

2.2.2. Feedstock Conversion in the Industrial Plant

2.3. Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

2.4. Interpretation

Results Evaluation

3. Results

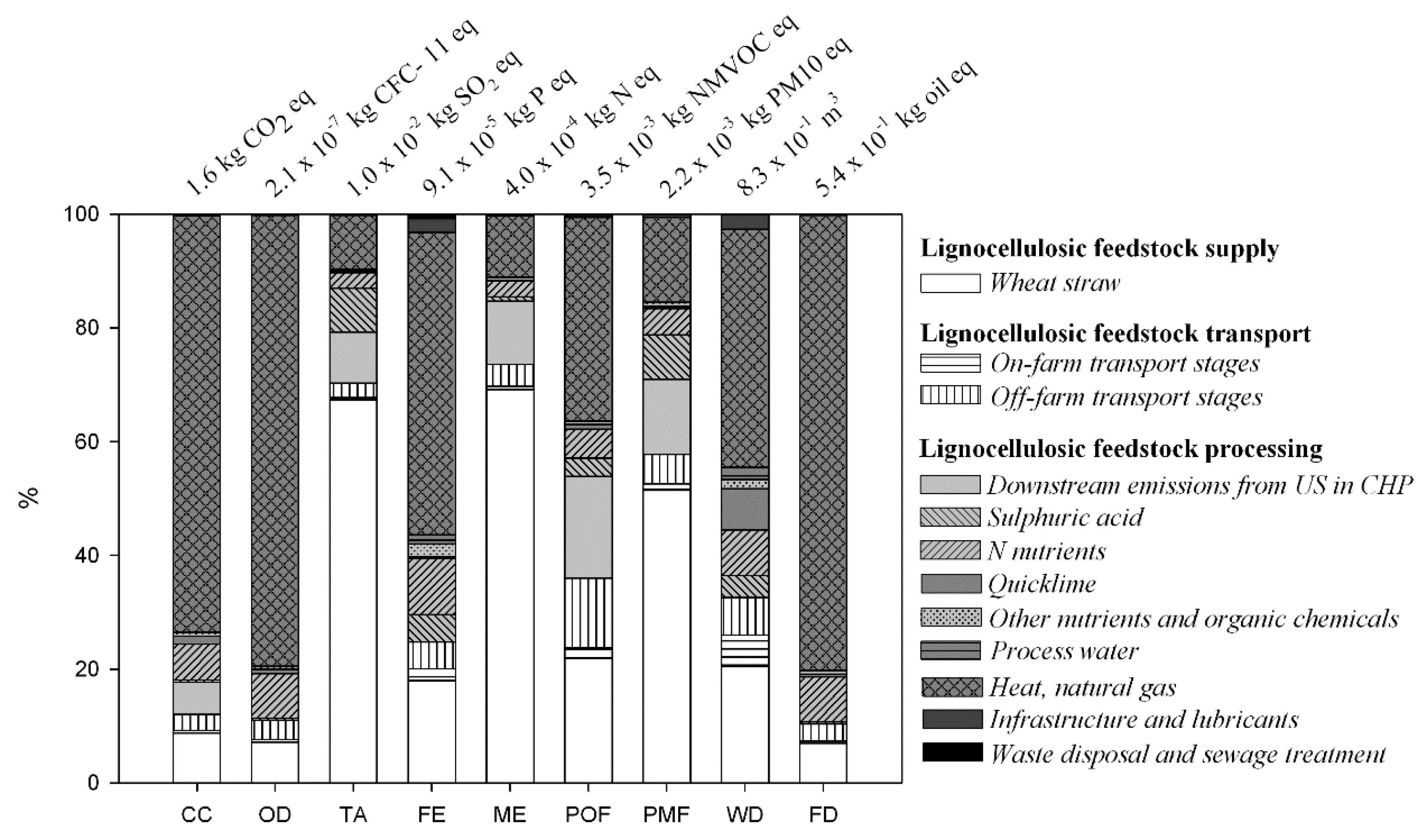

3.1. Cradle-to-Factory Gate Impacts of Bio-Based BDO

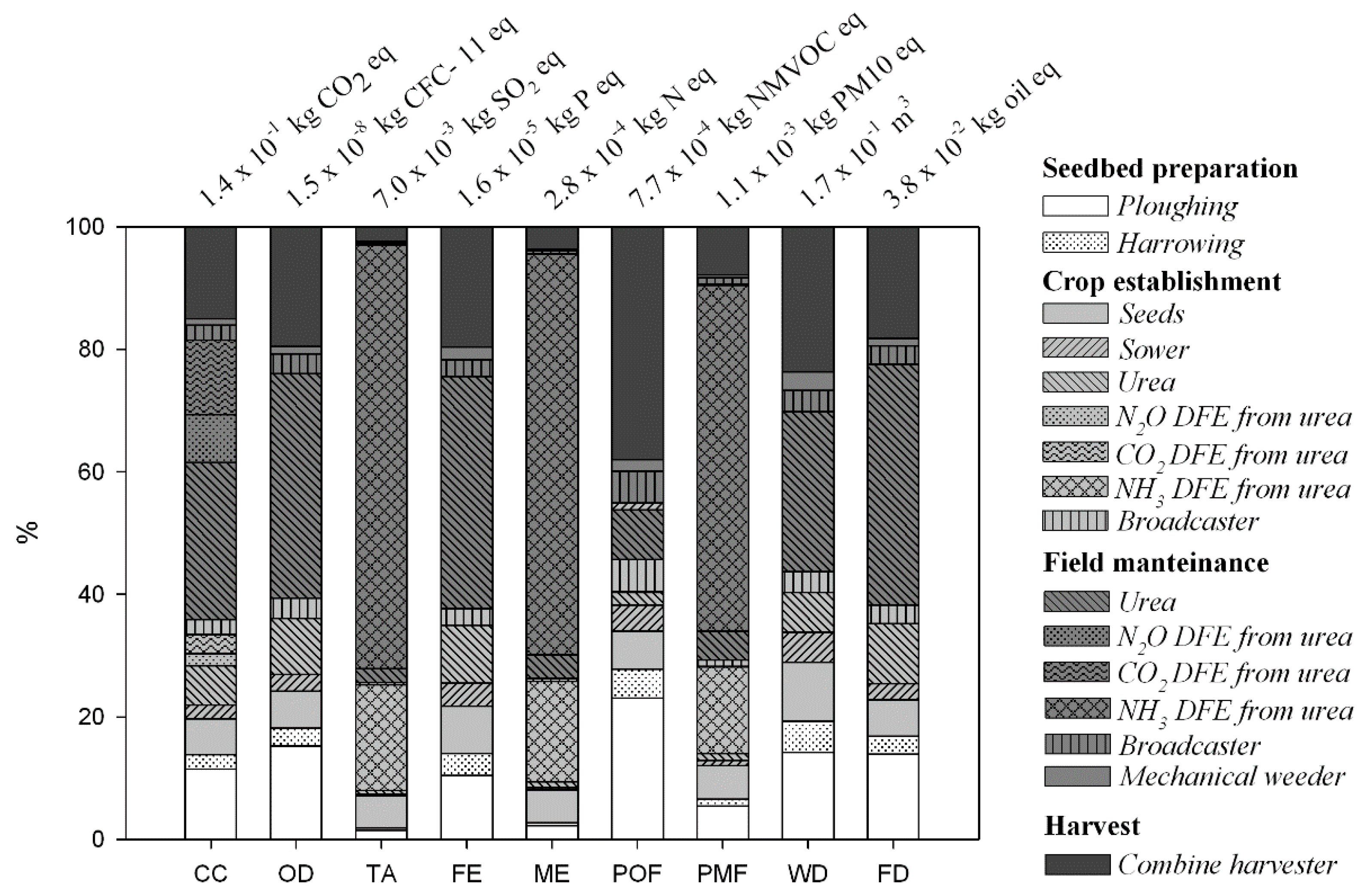

Cradle-to-Farm Gate Impacts of Lignocellulosic Feedstock Production

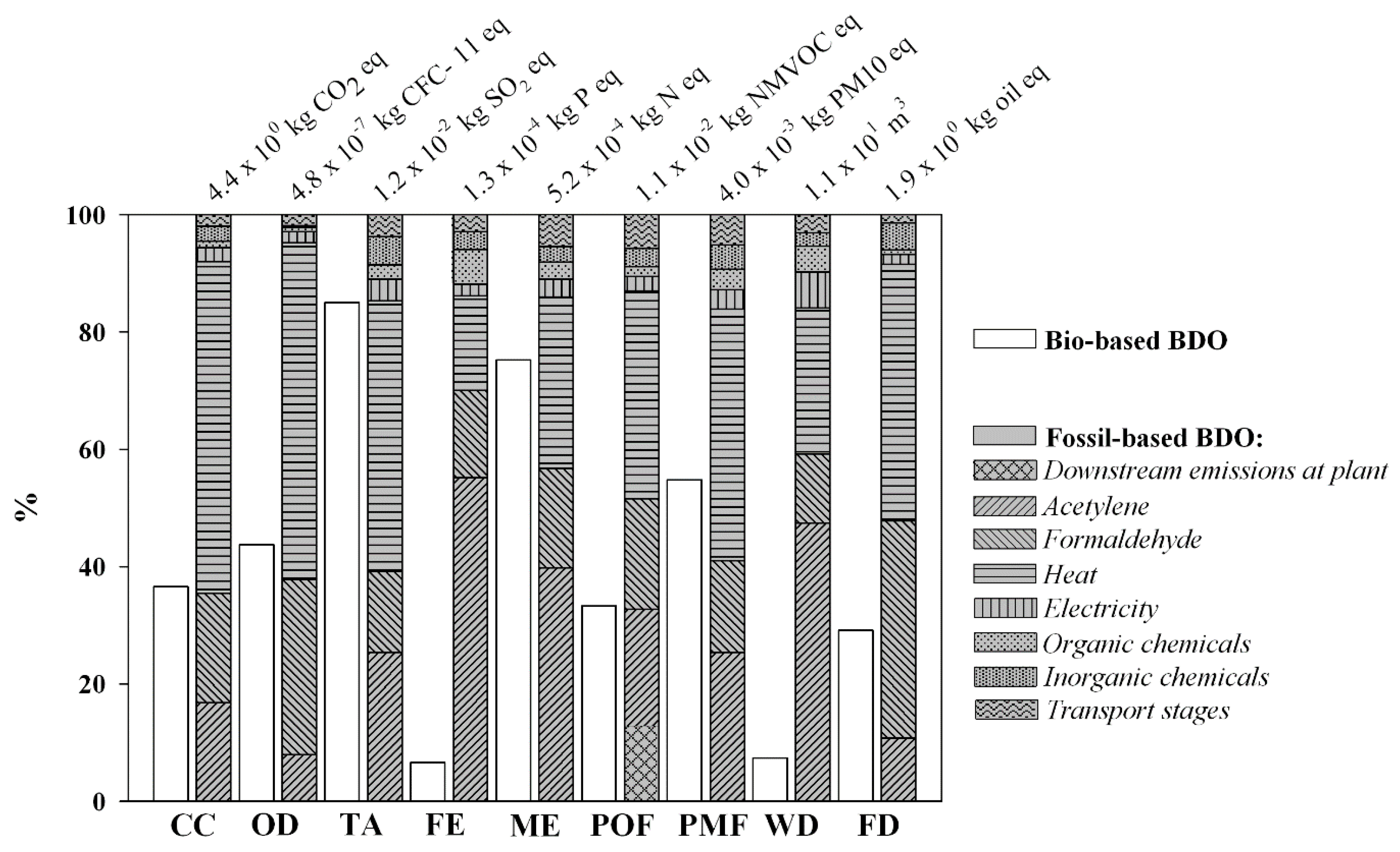

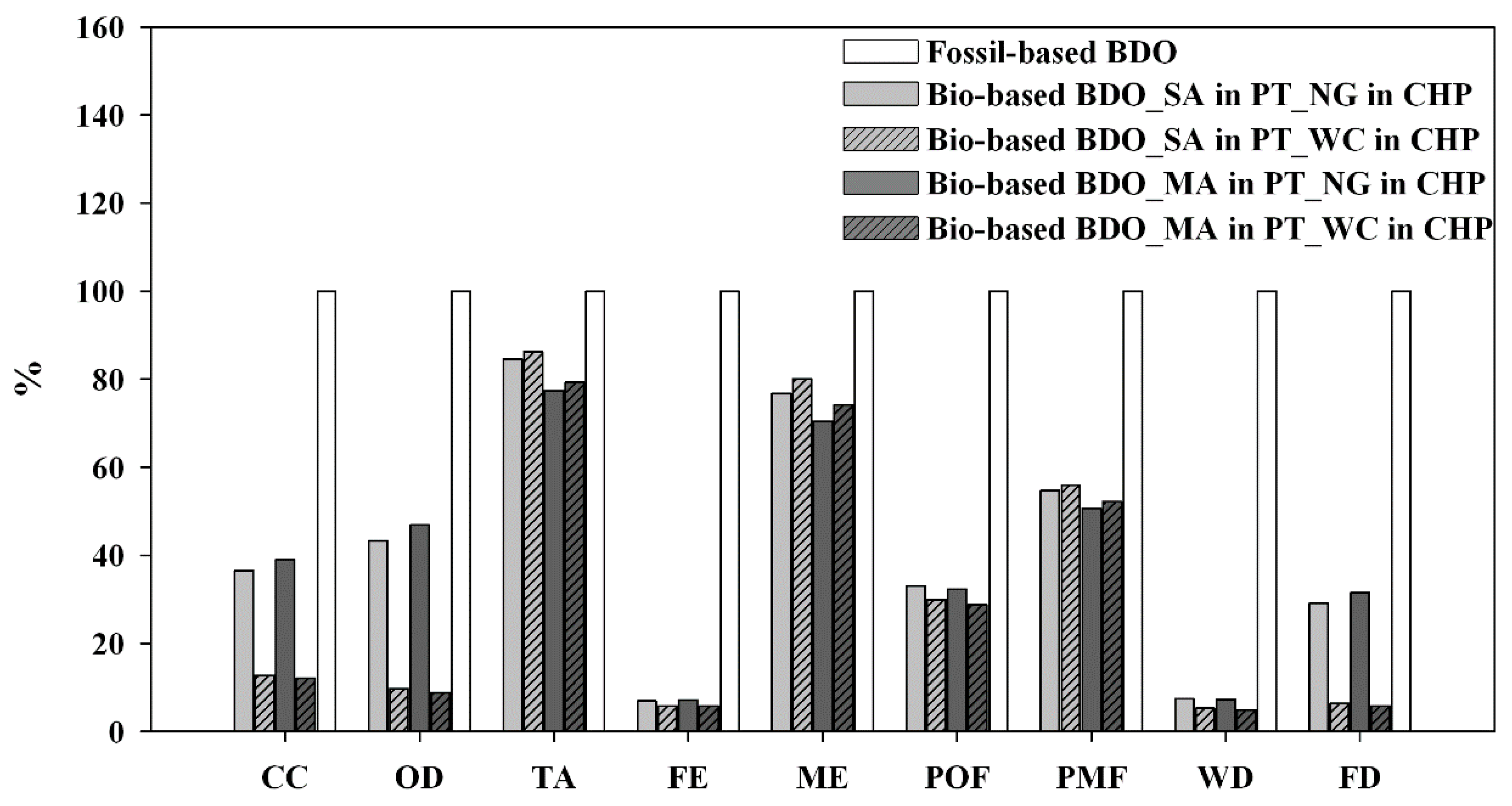

3.2. Bio-Based BDO vs. the Fossil Counterpart

3.3. Results Evaluation

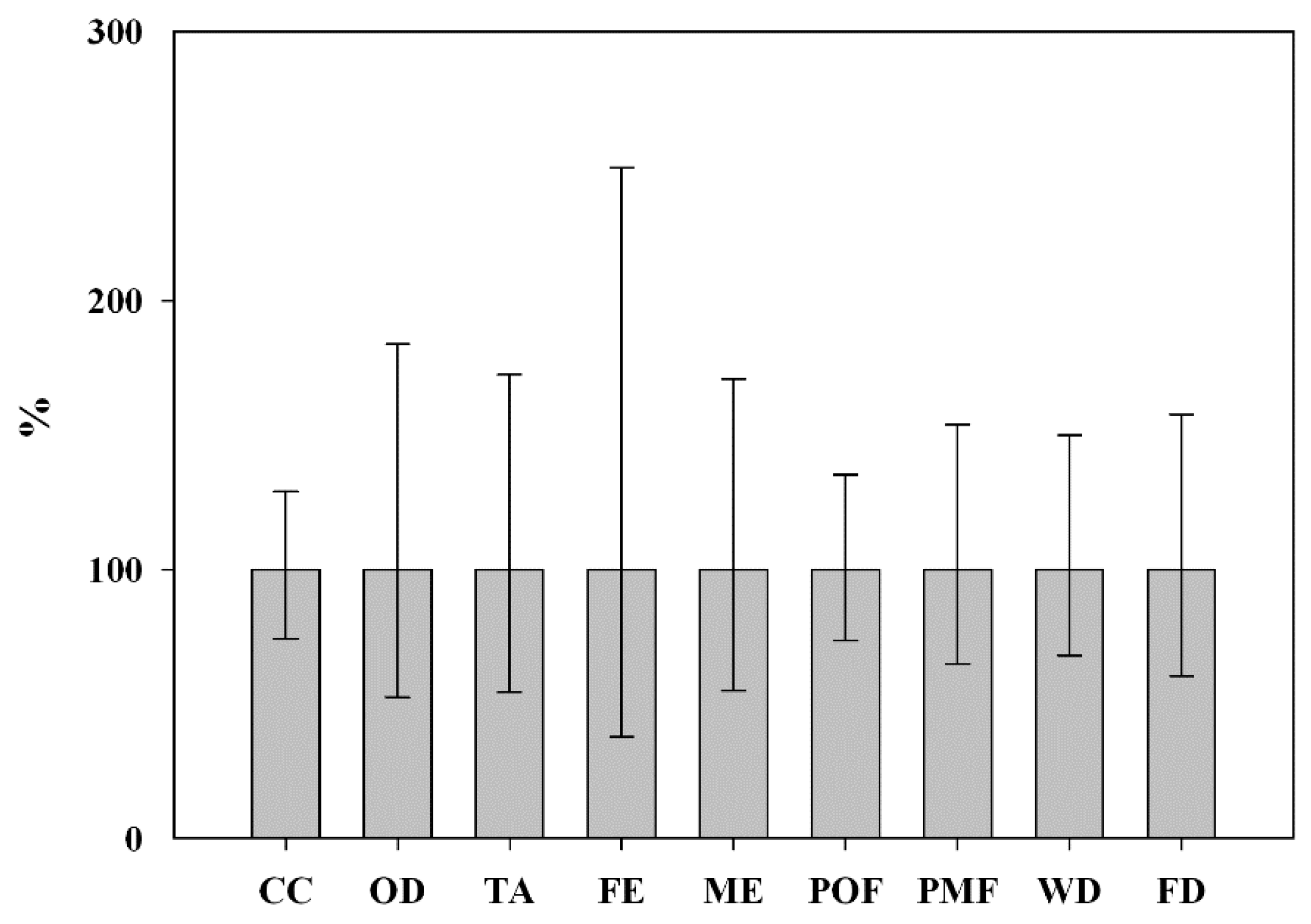

3.3.1. Uncertainty Analysis

3.3.2. Sensitivity Check

4. Discussion

4.1. Cradle-to-Factory Gate Impacts of Bio-Based BDO

4.2. Potential Benefits of Bio-Based BDO vs. the Fossil Counterpart

- Agronomic practices: The N fertilizer management could be implemented by optimizing fertilization rates and/or through the use of N formulations with reduced potential for NH3 volatilization, such as ammonium nitrate fertilizers [41] or urea-containing fertilizers with urease inhibitors to constrain the downstream emissions of NH3 [73,74,75]. However different rate and formulations of N fertilizer might result in different agronomic yields and costs of fertilization practice, which also should be taken in consideration. Similarly, the effective mitigation potential of inhibitors in terms of ammonia volatilization need to be further verified [76].

- Methodological assumptions: Site-specific NH3 volatilization emission and characterization factors would be beneficial for more reliable estimate of NH3 emissions from Mediterranean cropped soils, which appear not yet extensively investigated [46].

- Technical aspects inherent the industrial processing steps: Higher holocelluloses recovery efficiencies, as well as fermentation yields, would affect and restrain indirectly the environmental load of the crop phase. Considering all this, new analyses will be performed to test the benefits of other potential pathways for biomass processing (such as steam-explosion pre-treatment) and identify the most environmental promising routes to achieve scalable integrated biorefinery chains for BDO production.

4.3. Concerns about WS Feedstock Availability and Potential Competition with Current Use

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CC | Climate change; |

| OD | Ozone depletion; |

| TA | Terrestrial acidification; |

| FE | Freshwater eutrophication; |

| ME | Marine eutrophication; |

| POF | Photochemical oxidant formation; |

| PMF | Particulate matter formation; |

| WD | Water depletion; |

| FD | Fossil depletion; |

| SOC | Soil organic carbon; |

| WS | Wheat straw; |

| US | Uncorverted solids; |

| CHP | Combined Heat and Power. |

References

- Jackson, T. Motivating Sustainable Consumption; Centre for Environmental Strategy, University of Surrey: Guildford, UK, 2005; pp. 1–170. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Factbook 2010: Economic, Environmental and Social Statistics; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Towards Sustainable Household Consumption? Trends and Policies in OECD Countries; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2002; p. 158. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Household Behaviour and the Environment: Reviewing the Evidence; OECD: Paris, France, 2008; p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Promoting Sustainable Consumption: Good Practices in OECD Countries; OECD: Paris, France, 2008; p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Spread sustainable lifestyles 2050 Project, 2011. In Sustainable Lifestyles: Today’s Facts, Tomorrow’s Trends, Proceedings of the Seventh Framework Programme (FP7); Energy research Centre of the Netherlands: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament on the Sustainable Production and Consumption and Sustainable Industrial Policy Action Plan; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2008; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- White Paper—Roadmap to a Single European Transport Area? Towards a Competitive and Resource Efficient Transport System; COM 144 Final, 2011; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- Bibolet, E.R.; Fernando, G.E.; Shah, S.M. Renewable 1,4-Butanediol; Penn Libraries University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011; Available online: http://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1029&context=cbe_sdr (accessed on 22 April 2016).

- Yim, H.; Haselbeck, R.; Niu, W.; Pujol-Baxley, C.; Burgard, A.; Boldt, J.; Khandurina, J.; Trawick, J.D.; Osterhout, R.E.; Stephen, R.; et al. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for direct production of 1,4-butanediol. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, B.; Nelson, J.E.; Winters, P. Perspective on opportunities in industrial biotechnology in renewable chemicals. Biotechnol. J. 2012, 7, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, N.R.; Burgard, A.P.; Burk, M.J.; Crater, J.S.; Osterhout, R.E.; Pharkya, P.; Steer, B.A.; Sun, J.; Trawick, J.D.; Van Dien, S.J.; et al. An integrated biotechnology platform for developing sustainable chemical processes. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 42, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tecchio, P.; Freni, P.; De Benedetti, B.; Fenouillot, F. Ex-ante Life Cycle Assessment approach developed for a case study on bio-based polybutylene succinate. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- From the Sugar Platform to Biofuels and Biochemicals; Final Report for the European Commission, Contract No. ENER/C2/423-2012/SI2.673791; E4tech Ltd.: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–183.

- Mang, M. Bio-Based Succinic Acid: Transforming the Chemicals Industry. Available online: http://www.myriant.com/pdf/Myriant_SCM_May2012.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2012).

- Adom, F.; Dunn, J.B.; Han, J.; Sather, N. Life-Cycle Fossil Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Bioderived Chemicals and Their Conventional Counterparts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 14624–14631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roes, A.L.; Patel, M.K. Ex-ante environmental assessments of novel technologies e improved caprolactam catalysis and hydrogen storage. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1659–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabone, M.D.; Cregg, J.J.; Beckman, E.J.; Landis, A.E. Sustainability Metrics: Life Cycle Assessment and Green Design in Polymers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 8264–8269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environmental Management Life Cycle Assessment Principles and Framework; ISO 14040 (International Standard); International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Environmental Management Life Cycle Assessment Requirements and Guidelines; ISO 14044 (International Standard); International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Lankey, R.; Anastas, P. Life-Cycle Approaches for Assessing Green Chemistry Technologies. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2002, 41, 4498–4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cok, B.; Tsiropoulos, I.; Roes, A.L.; Patel, M.K. Succinic Acid Production Derived from Carbohydrates: An Energy and Greenhouse Gas Assessment of a Platform Chemical toward a Bio-based Economy. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2014, 8, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.; Adom, F.; Sather, N.; Han, J.; Snyder, S. Life-cycle Analysis of Bioproducts and Their Conventional Counterparts in GREET™; Argonne National Laboratory: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Venkata Mohan, S.; Nikhil, G.N.; Chiranjeevi, P.; Nagendranatha Reddy, C.; Rohit, M.V.; Naresh Kumar, A.; Sarkar, O. Waste Biorefinery Models towards Sustainable Bioeconomy: Critical Review and Future Perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, H.H.; Tan, R.B.; Chng, K.W. Environmental impacts of conventional plastic and bio-based carrier bags. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gironi, F.; Piemonte, V. Life Cycle Assessment of Polylactic Acid and Polyethylene Terephthalate Bottles for Drinking Water. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2011, 30, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, Y.; Mizukoshi, T. Bionolle (Polybutylenesuccinate). In Synthetic Biodegradable Polymers; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 245, pp. 285–313. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, R.A.; Bakshi, B.R. 1,3-Propanediol from Fossils versus Biomass: A Life Cycle Evaluation of Emissions and Ecological Resources. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 8068–8082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammens, T.M.; Potting, J.; Sanders, J.P.M.; De Boer, I.J.M. Environmental Comparison of Biobased Chemicals from Glutamic Acid with Their Petrochemical Equivalents. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 8521–8528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Reference Life Cycle Data System (ILCD) Handbook—General Guide for Life Cycle Assessment—Detailed Guidance; First Edition March 2010; EUR 24708 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, Luxembourg, 2010.

- Supporting Environmentally Sound Decisions for Waste Management—A Technical Guide to Life Cycle Thinking (LCT) and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) for Waste Experts and LCA Practitioners; EUR 24916 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, Luxembourg, 2011.

- Burgess, A.A.; Brennan, D.J. Application of life cycle assessment to chemical processes. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2001, 56, 2589–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SimaPro. Pré Consultants; LE Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Goedkoop, M.; Heijungs, R.; Huijbregts, M.; De Schryver, A.; Struijs, J.; van Zelm, R. A Life Cycle Impact Assessment Method Which Comprises Harmonised Category Indicators at the Midpoint and Endpoint Level; ReCiPe 2008; Dutch Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and Environment (VROM): The Hague, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Camera di Commercio Avellino, Regione Campania, Avellino, Italy. Available online: http://www.av.camcom.gov.it (accessed on 22 November 2015).

- Camera di Commercio Forlì-Cesena, Regione Emilia Romagna, Forlì, Italy. Available online: http://www.fc.camcom.it/ (accessed on 22 November 2015).

- Frischknecht, R.; Jungbluth, N.; Althaus, H.-J.; Doka, G.; Dones, R.; Heck, T.; Hellweg, S.; Hischier, R.; Nemecek, T.; Rebitzer, G. The ecoinvent database: Overview and methodological framework. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2005, 10, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ENEA, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development. Valutazione del Potenziale Energetico delle Biomasse Vegetali della Regione Campania: Piano Energetico della Regione Campania; Published bythe Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development: Roma, Italy, 2001; pp. 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Regione Campania. Disciplinari di Produzione Integrate. DGR n. 50 del 28/02/2014. 2014. Available online: http://www.agricoltura.regione.campania.it (accessed on 22 November 2015).

- Regione Campania. Piano Regionale Prevenzione Incendi Boschivi. Delibera della Giunta Regionale n. 330 del 08/08/2014, BURC n. 58 del 11 Agosto. Available online: http://burc.regione.campania.it (accessed on 22 November 2015).

- CRA, Consiglio per la Ricerca e l’agricoltura. Le Varietà di Frumento Duro in Italia. Risultati della Rete Nazionale di Sperimentazione 1999–2012; Ministero delle Politiche Agricole e Forestali: Roma, Italy, 2012; pp. 2–176. Available online: http://sito.entecra.it/portale/public/documenti/volume_fd_2013_redux.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2016).

- Corbeels, M.; Hofman, G.; Van Cleemput, O. Fate of fertiliser N applied to winter wheat growing on a Vertisol in a Mediterranean environment. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 1999, 53, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, A.; Michelena, A.; Lloveras, J. Effects of nitrogen supply on wheat and on soil nitrate. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 25, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noureldin, N.A.; Saudy, H.S.; Ashmawy, F.; Saed, H.M. Grain yield response index of bread wheat cultivars as influenced by nitrogen levels. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2013, 58, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sestak, I.; Mesic, M.; Zgorelec, Z.; Kisic, I.; Basic, F. Winter wheat agronomic traits and nitrate leaching under variable nitrogen fertilization. Plant Soil Environ. 2014, 60, 394–400. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, A.; Zucaro, A.; Fagnano, M.; Bastianoni, S.; Basosi, R.; Fierro, A. LCA of Arundo donax L. lignocellulosic feedstock production under Mediterranean conditions. Biomass. Bioenergy 2015, 73, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemecek, T.; Shnetzer, J. Direct Field Emissions and Elementary Flows in LCIs of Agricultural Production Systems; Updating of Agricultural LCIs for EcoInventData v3.0, Agroscope Reckenholz-Tanikon Research Station ART: Taenikon, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC, 2006. National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme.IPCC Intergovernamental Panel of Climate Change Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. In Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use; Eggleston, H.S.; Buendia, L.; Miwa, K.; Ngara, T.; Tanabe, K. (Eds.) IGES: Hayama, Japan, 2006.

- Diodato, N.; Fagnano, M.; Alberico, I.; Chirico, G.B. Mapping soil erodibility from composed data set in Sele River Basin, Italy. Nat. Hazards 2011, 58, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agritrasfer, 2007. Normetecniche di coltura- Frumentoduro. Agritrasfer-in-Sud Project (D.M. MiPAAF n.254/7303/07 del 08/11/2007), ServizioInnovazione e TrasferimentoTecnologico, Consiglio per la Ricerca e la sperimentazione in Agricoltura (CRA). Available online: http://cdp-agritrasfer.entecra.it/ (accessed on 22 November 2015).

- Sistema Informativo Nazionale per lo Sviluppodell’agricoltura, Online Statistics. Available online: http://www.sin.it/portal/page/portal/SINPubblico (accessed on 22 November 2015).

- Lee, D.K.; Owens, V.N.; Boe, A.; Jeranyama, P. Composition of Herbaceous Biomass Feedstocks; Plant Science Department, South Dakota State University: Brookings, SD, USA, 2007; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Volynets, B.; Dahman, Y. Assessment of pretreatments and enzymatic hydrolysis of wheat straw as a sugar source for bioprocess industry. Int. J. Energy Environ. 2011, 2, 427–446. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, H.A.; Cerqueira, M.A.; Silva, H.D.; Rodríguez-Jasso, R.M.; Vicente, A.A.; Teixeira, J.A. Biorefinery valorization of autohydrolysis wheat straw hemicellulose to be applied in a polymer-blend film. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 92, 2154–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jungbluth, N.; Chudacoff, M.; Dauriat, A.; Dinkel, F.; Doka, G.; Faist Emmenegger, M.; Gnansounou, E.; Kljun, N.; Schleiss, K.; Spielmann, M.; et al. Life Cycle Inventory of Bioenergy; Ecoinvent Report No. 17; Swiss Centre for Life Cycle Inventories: Dübendorf, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Phyllis2, Database for Biomass and Waste. Available online: https://www.ecn.nl/phyllis2 (accessed on 22 November 2015).

- Sleeswijk, A.W.; van Oers, L.F.; Guin_ee, J.B.; Huijbregts, M.A.J. Normalization in product life cycle assessment: An LCA of the global and European economic systems in the year 2000. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 390, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazio, S.; Monti, A. Life cycle assessment of different bioenergy production systems including perennial and annual crops. Biomass. Bioenergy 2011, 35, 4868–4878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, M.C.; Keoleian, G.A.; Volk, T.A. Life cycle assessment of a willow bioenergy cropping system. Biomass. Bioenergy 2003, 25, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renouf, M.A.; Wegener, M.K.; Nielsen, L.K. An environmental life cycle assessment comparing Australian sugarcane with US corn and UK sugar beet as producers of sugars for fermentation. Biomass. Bioenergy 2008, 32, 1144–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherubini, F.; Jungmeier, G. LCA of a biorefinery concept producing bioethanol, bioenergy, and chemicals from switchgrass. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erisman, J.L.; Grinsven, H.; Leip, A.; Mosier, A.; Bleeker, A. Nitrogen and biofuels: An overview of the current state of knowledge. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2010, 86, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renouf, M.A.; Wegener, M.K.; Pagan, R.J. Life cycle assessment of Australian sugarcane production with a focus on sugarcane growing. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godard, C.; Boissy, J.; Gabrielle, B. Life-cycle assessment of local feedstock supply scenarios to compare candidate biomass sources. Glob. Chang. Biol. Bioenergy 2013, 5, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessou, C.; Basset-Mens, C.; Tran, T.; Benoist, A. LCA applied to perennial cropping systems: A review focused on the farm stage. Int. J. LCA 2013, 18, 340–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, T.M.; Smith, R.L.; Young, D.M.; Costa, C.A. Evaluating the Environmental Friendliness, Economics and Energy Efficiency of Chemical Processes: Heat Integration. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2003, 5, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patt, J.J.; Banholzer, W.F. Improving Energy Efficiency in the Chemical Industry; The Bridge, National Academy of Engineering: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; pp. 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Groot, W.J.; Borén, T. Life cycle assessment of the manufacture of lactide and PLA biopolymers from sugarcane in Thailand. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 970–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnawornrungsee, R.; Malakul, P.; Mungcharoen, T. Life Cycle Energy and Environmental Analysis Study of a Model Biorefinery in Thailand. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2013, 32, 439–444. [Google Scholar]

- Gurram, R.; Al-Shannag, M.; Knapp, S.; Das, T.; Singsaas, E.; Alkasrawi, M. Technical possibilities of bioethanol production from coffee pulp: A renewable feedstock. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2016, 18, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.; Quintero, J.; Conejeros, R.; Aroca, G. Life cycle assessment of lignocellulosic bioethanol: Environmental impacts and energy balance. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 1349–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrionn, A.L.; McManus, M.C.; Hammond, G.P. Environmental life cycle assessment of lignocellulosic conversion to ethanol: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 4638–4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, A.; Diez, J.A.; López-Valdivia, L.M.; Gascó, A.; Jimènez, J. Nitrous oxide emissions and denitrification N-losses from soils treated with isobutyldendiurea and urea plus dicyandiamide. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2001, 34, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Cobena, A.; Misselbrook, T.H.; Arce, A.; Mingot, J.I.; Diez, J.A.; Vallejo, A. An inhibitor of urease activity effectively reduces ammonia emissions from soil treated with urea under Mediterranean conditions. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008, 126, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Cobena, A.; Sánchez-Martın, L.; Garcıa-Torres, L.; Vallejo, A. Gaseous emissions of N2O and NO and NO3− leaching from urea applied with urease and nitrification inhibitors to a maize (Zea mays) crop. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 149, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.G.; Saggar, S.; Roudier, P. The effect of nitrification inhibitors on soil ammonia emissions in nitrogen managed soils: A meta-analysis. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2012, 93, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skott, T. Straw to Energy Status, Tech and Innovation in Denmark 2011; Published by Agro Business Park A/S: Tjele, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Glithero, N.J.; Wilson, P.; Ramsden, S.J. Straw use and availability for second generation biofuels in England. Biomass. Bioenergy 2013, 55, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, F.; Kindred, D.; Bhogal, A.; Roques, S.; Kerley, J.; Twining, S.; Brassington, T.; Gladders, P.; Balshaw, H.; Cook, S.; et al. Straw Incorporation Review; Published by is the Cereals and Oilseeds Division (HGCA) of the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board: Kenilworth Warwickshire, UK, 2014; p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- Glithero, N.J.; Ramsden, S.J.; Wilson, P. Farm systems assessment of bioenergy feedstock production: Integrating bio-economic models and life cycle analysis approaches. Agric. Syst. 2012, 109, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarkalson, D.D.; Brown, B.; Kok, H.; Bjorneberg, D. Irrigated small grain residue management effects on soil chemical and physical properties and nutrient cycling. Soil Sci. 2009, 174, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkalson, D.D.; Brown, B.; Kok, H.; Bjorneberg, D. Small Grain Residue Management Effects on Soil Organic Carbon: A Literature Review. Agron. J. 2011, 103, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lu, M.; Cui, J.; Li, B.; Fang, C. Effects of straw carbon input on carbon dynamics in agricultural soils: A meta-analysis. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2014, 20, 1366–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Agronomic Input/Output a | Unit | BG | Uncertainity Range | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB | UB | D | |||||

| Input a | Soil preparation | Tillage, ploughing | n.·ha−1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | Triangular |

| Tillage, harrowing | n.·ha−1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | Triangular | ||

| Sowing | Wheat seeds | kg·ha−1 | 190 | 87 | 285 | Triangular | |

| Sowing | n.·ha−1 | 1 | – | – | – | ||

| Triple superphosphate, as P2O5 | kg·ha−1 | 0 | 0 | 70 | Triangular | ||

| Potassium sulphate, as K2O | kg·ha−1 | 0 | 0 | 70 | Triangular | ||

| Urea, as N | kg·ha−1 | 20 | 0 | 26 | Triangular | ||

| Fertilizing, by broadcaster | n.·ha−1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | Triangular | ||

| Field maintenance | Urea, as N | kg·ha−1 | 80 | 60 | 104 | Triangular | |

| Fertilizing, by broadcaster | n.·ha−1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Triangular | ||

| Tillage, currying, by weeder | n.·ha−1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | Triangular | ||

| Pesticide | kg·ha−1 | 0 | 0 | 1.6 | Triangular | ||

| Application of pesticide | n.·ha−1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Triangular | ||

| Irrigation water | m3·ha−1 | 0 | 0 | 400 | Triangular | ||

| Harvest | Combine harvesting | n.·ha−1 | 1 | – | – | – | |

| Output | Yields | Grain b | ton·ha−1 | 3.1 | 2.1 | 6.2 | Uniform |

| Straw c | ton·ha−1 | 5.6 | 3.8 | 11.2 | Uniform | ||

| Agronomic DFE d | NH3, volatilized | kg·ha−1 | 18.2 | 7.4 | 31.6 | Uniform | |

| N2O, biogenic | kg·ha−1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 2.8 | Uniform | ||

| NO3 leached | kg·ha−1 | 0 | 0 | 274.6 | Uniform | ||

| CO2 fossil from N-urea | kg·ha−1 | 157 | 94.2 | 204.1 | Uniform | ||

| PO43− runoff to surface water | kg·ha−1 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | Uniform | ||

| PO43− leaching to ground water | kg·ha−1 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | Uniform | ||

| P runoff to surface water | kg·ha−1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | Uniform | ||

| Industrial Input/Output | Amount | Unit Measure | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Water a | 5.8 | kg·kg−1BDO |

| Sulphuric acid | 0.06 | kg·kg−1BDO | |

| Nutrients and organic chemicals b | 0.3 | kg·kg−1BDO | |

| Quicklime | 0.05 | kg·kg−1BDO | |

| Total energy consumptionc | 41 | MJ·kg−1BDO | |

| Output | BDO-bio | 1 | kg |

| Parameter | Unit | BG | Uncertainty Range | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB | UB | D | |||

| Dry matter input a | kg·kg−1ws(db) | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.56 | Uniform |

| Carbon input, biogenic a | kg·kg−1ws(db) | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.32 | Uniform |

| Energy input b | MJ·kg−1US | 8.9 | 8.7 | 9.5 | Uniform |

| Heat production c | MJ·kg−1BDO | 20 | 13 | 35 | Uniform |

| Electricity production d | kWh·kg−1BDO | 2 | 1 | 2 | Uniform |

| C Biogenic | KgCkg−1 BDO |

|---|---|

| Input 1 | – |

| C in WS feedstock | 2 |

| Output 1 | – |

| C in bio-based BDO | 0.5 |

| C in downstream emissions from industrial processing of WS feedstock 2: | – |

| Co-fermentation | – |

| C–CO2 | 0.3 |

| US combustion in CHP | – |

| C–CH4 1 | 6 × 10−6 |

| C–CO 1 | 6 × 10−5 |

| C-non methan organic compounds 2 | 8 × 10−5 |

| C–CO2 1 | 1.2 |

| Total output C | 2 |

| Impact Category | Total Impact | Impact from Key Input Process | Input/Output | Impact from Key Pollutant Input/Output | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean a | SD b | CI c | Mean | SD b | CI c | Mean | SD b | CI c | |||||

| 2.5% | 97.5% | 2.5% | 97.5% | 2.5% | 97.5% | ||||||||

| Additional Heat | Key Input/Output from Additional Heat | ||||||||||||

| CC (kg CO2 eq) | 1.6 × 100 | 2.4 × 10−1 | 1.2 × 100 | 2.1 × 100 | 1.1 × 100 | 2.2 × 10−1 | 7.6 × 10−1 | 1.6 × 100 | CO2 (Ds, fossil) | 1.1 × 100 | 2.0 × 10−1 | 7.2 × 10−1 | 1.5 × 100 |

| OD (kg CFC-11 eq) | 2.0 × 10−7 | 7.0 × 10−8 | 1.1 × 10−7 | 3.8 × 10−7 | 1.6 × 10−7 | 6.5 × 10−8 | 7.3 × 10−8 | 3.2 × 10−7 | Halon 1211 (Us) | 1.5 × 10−7 | 6.4 × 10−8 | 6.9 × 10−8 | 3.1 × 10−7 |

| FE (kg P eq) | 9.2 × 10−5 | 5.5 × 10−5 | 3.5 × 10−5 | 2.3 × 10−4 | 4.7 × 10−5 | 3.6 × 10−5 | 1.2 × 10−5 | 1.4 × 10−4 | Phosphate (Us) | 4.7 × 10−5 | 3.6 × 10−5 | 1.2 × 10−5 | 1.4 × 10−4 |

| POF (kg NMVOC eq) | 3.6 × 10−3 | 5.7 × 10−4 | 2.6 × 10−3 | 4.9 × 10−3 | 1.2 × 10−3 | 4.0 × 10−4 | 6.3 × 10−4 | 2.2 × 10−3 | NO× (Us/Ds) | 8.1 × 10−4 | 3.2 × 10−4 | 3.7 × 10−4 | 1.6 × 10−3 |

| WD (m3) | 8.4 × 10−1 | 1.7 × 10−1 | 5.7 × 10−1 | 1.3 × 100 | 3.3 × 10−1 | 1.4 × 10−1 | 1.5 × 10−1 | 6.7 × 10−1 | Water (Us, turbin) | 3.3 × 10−1 | 1.4 × 10−1 | 1.5 × 10−1 | 6.7 × 10−1 |

| FD (kg oil eq) | 5.3 × 10−1 | 1.4 × 10−1 | 3.2 × 10−1 | 8.4 × 10−1 | 4.2 × 10−1 | 1.3 × 10−1 | 2.3 × 10−1 | 7.1 × 10−1 | Natural gas (Us) | 4.1 × 10−1 | 1.2 × 10−1 | 2.2 × 10−1 | 7.0 × 10−1 |

| Wheat Straw | Input/Output | Key Output from Wheat Straw | |||||||||||

| TA (kg SO2 eq) | 1.2 × 10−2 | 3.8 × 10−3 | 6.7 × 10−3 | 2.1 × 10−2 | 8.8 × 10−3 | 3.6 × 10−3 | 3.4 × 10−3 | 1.7 × 10−2 | NH3 (DFE) | 8.2 × 10−3 | 3.5 × 10−3 | 3.0 × 10−3 | 1.7 × 10−2 |

| ME (kg N eq) | 4.8 × 10−4 | 1.4 × 10−4 | 2.6 × 10−4 | 8.1 × 10−4 | 3.5 × 10−4 | 1.4 × 10−4 | 1.4 × 10−4 | 6.8 × 10−4 | NH3 (DFE) | 3.1 × 10−4 | 1.3 × 10−4 | 1.1 × 10−4 | 6.2 × 10−4 |

| PMF (kg PM10 eq) | 2.4 × 10−3 | 5.6 × 10−4 | 1.6 × 10−3 | 3.8 × 10−3 | 1.4 × 10−3 | 5.1 × 10−4 | 6.1 × 10−4 | 2.6 × 10−3 | NH3 (DFE) | 1.1 × 10−3 | 4.6 × 10−4 | 3.9 × 10−4 | 2.2 × 10−3 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Forte, A.; Zucaro, A.; Basosi, R.; Fierro, A. LCA of 1,4-Butanediol Produced via Direct Fermentation of Sugars from Wheat Straw Feedstock within a Territorial Biorefinery. Materials 2016, 9, 563. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9070563

Forte A, Zucaro A, Basosi R, Fierro A. LCA of 1,4-Butanediol Produced via Direct Fermentation of Sugars from Wheat Straw Feedstock within a Territorial Biorefinery. Materials. 2016; 9(7):563. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9070563

Chicago/Turabian StyleForte, Annachiara, Amalia Zucaro, Riccardo Basosi, and Angelo Fierro. 2016. "LCA of 1,4-Butanediol Produced via Direct Fermentation of Sugars from Wheat Straw Feedstock within a Territorial Biorefinery" Materials 9, no. 7: 563. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9070563

APA StyleForte, A., Zucaro, A., Basosi, R., & Fierro, A. (2016). LCA of 1,4-Butanediol Produced via Direct Fermentation of Sugars from Wheat Straw Feedstock within a Territorial Biorefinery. Materials, 9(7), 563. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9070563