Fabrication of Microfiber Patterns with Ivy Shoot-Like Geometries Using Improved Electrospinning

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

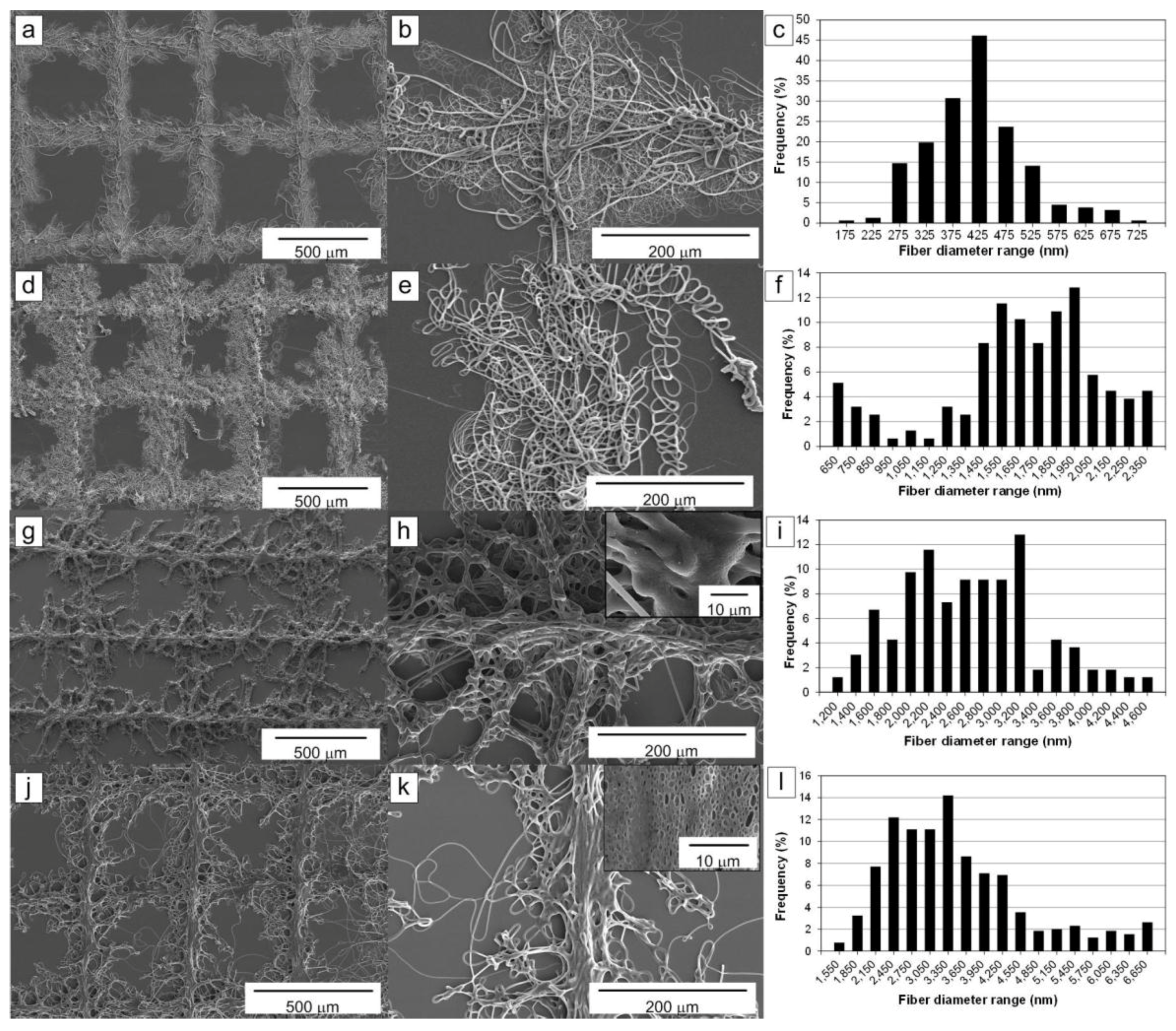

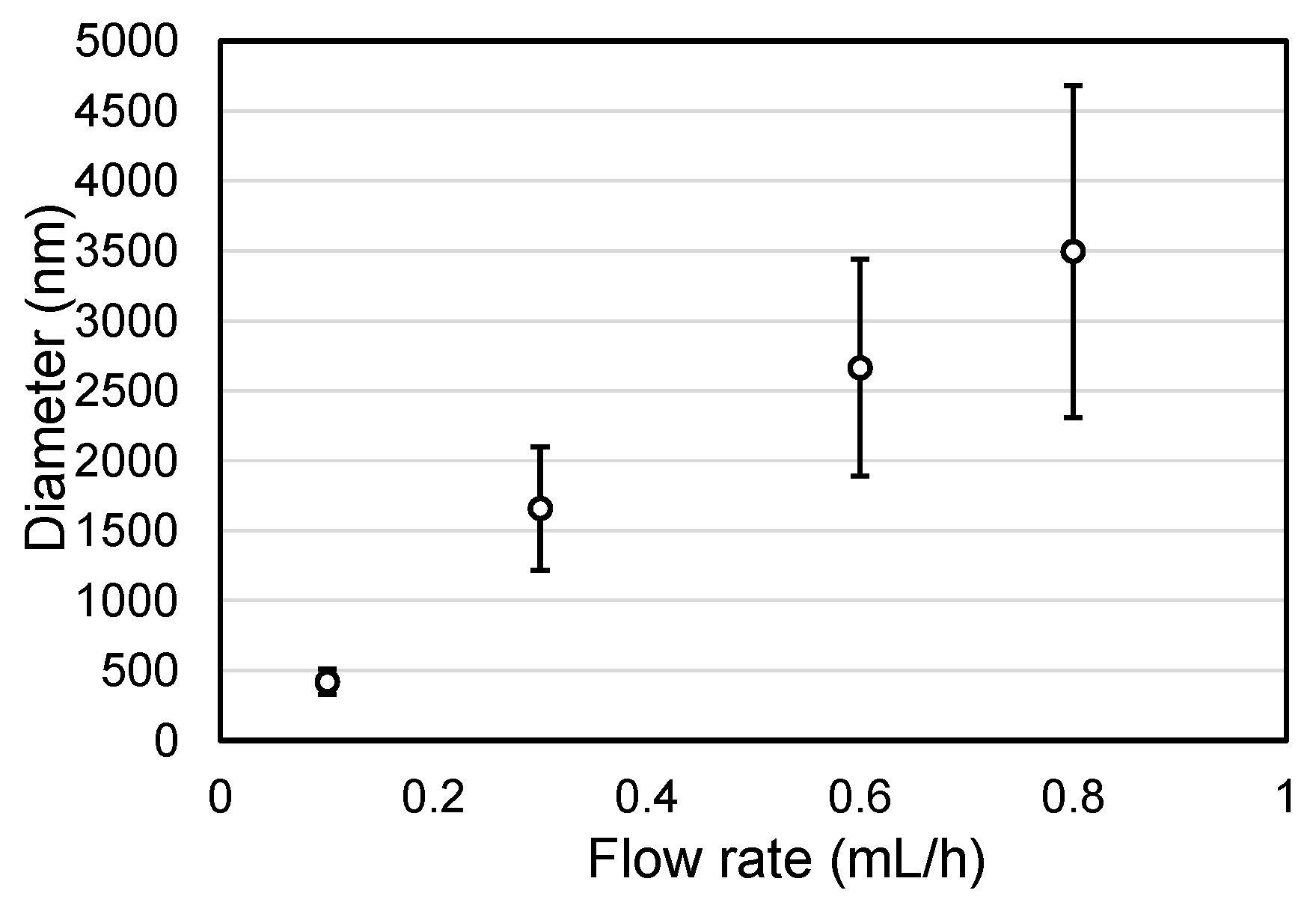

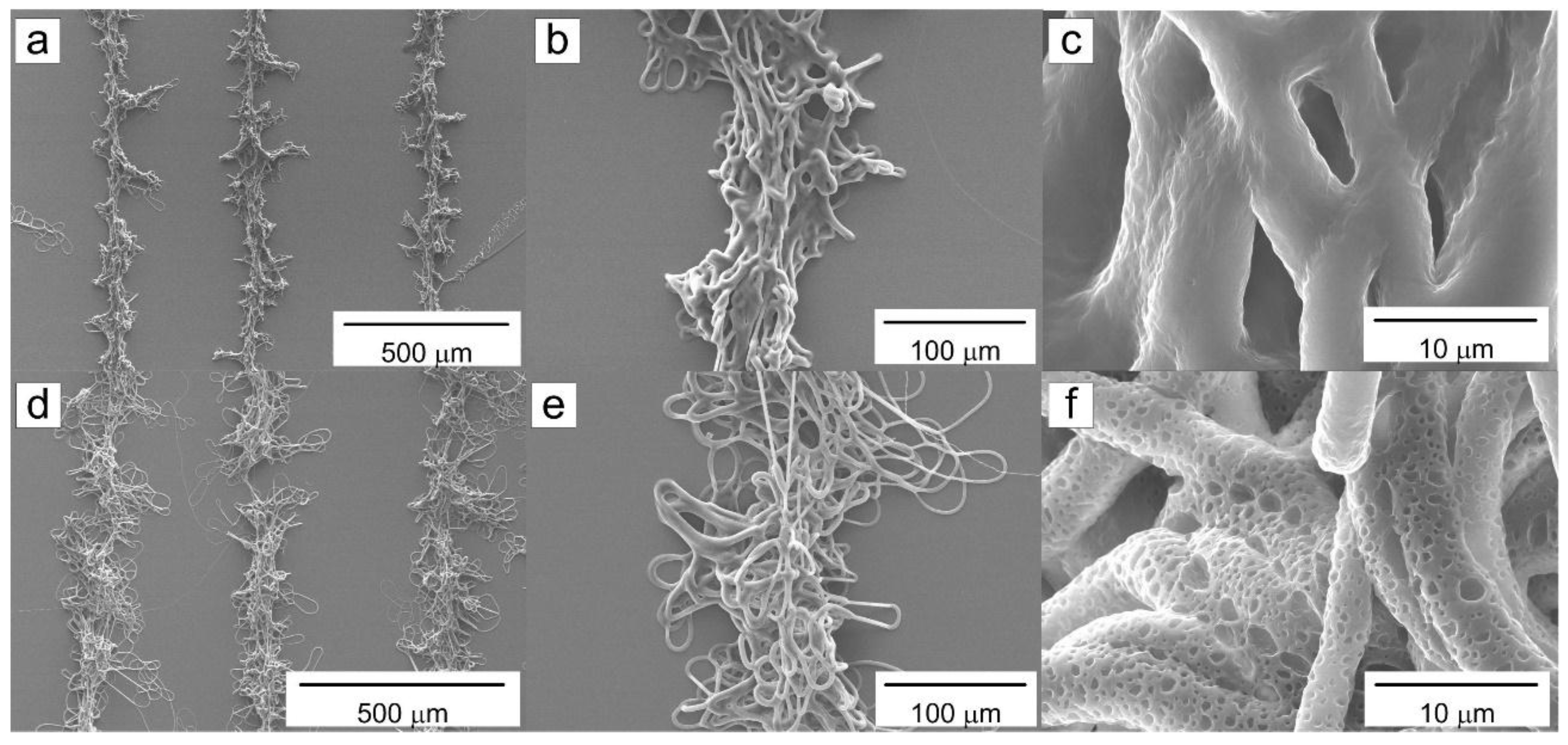

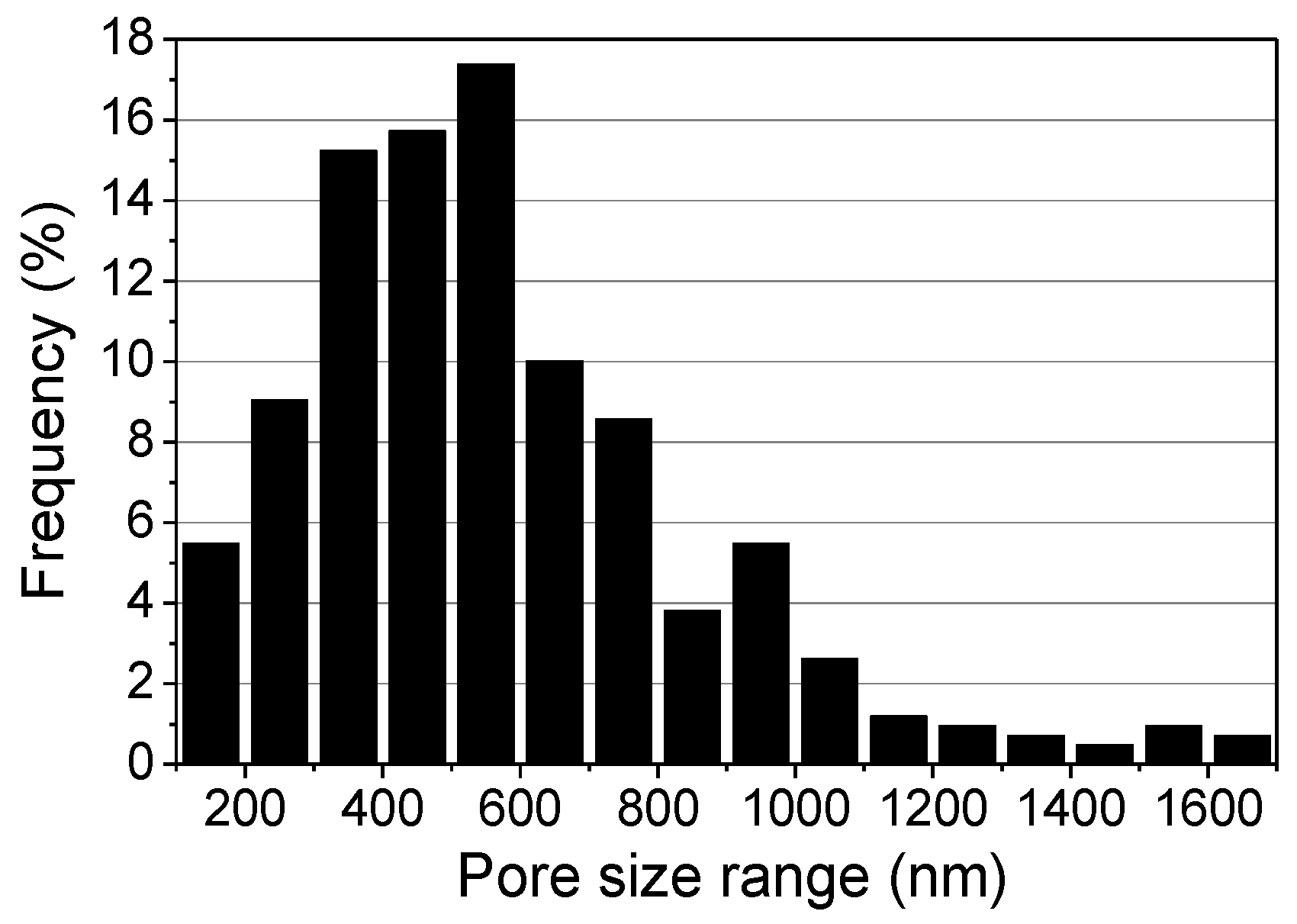

2.1. Influence of the Solution Flow Rate on the Microfibers

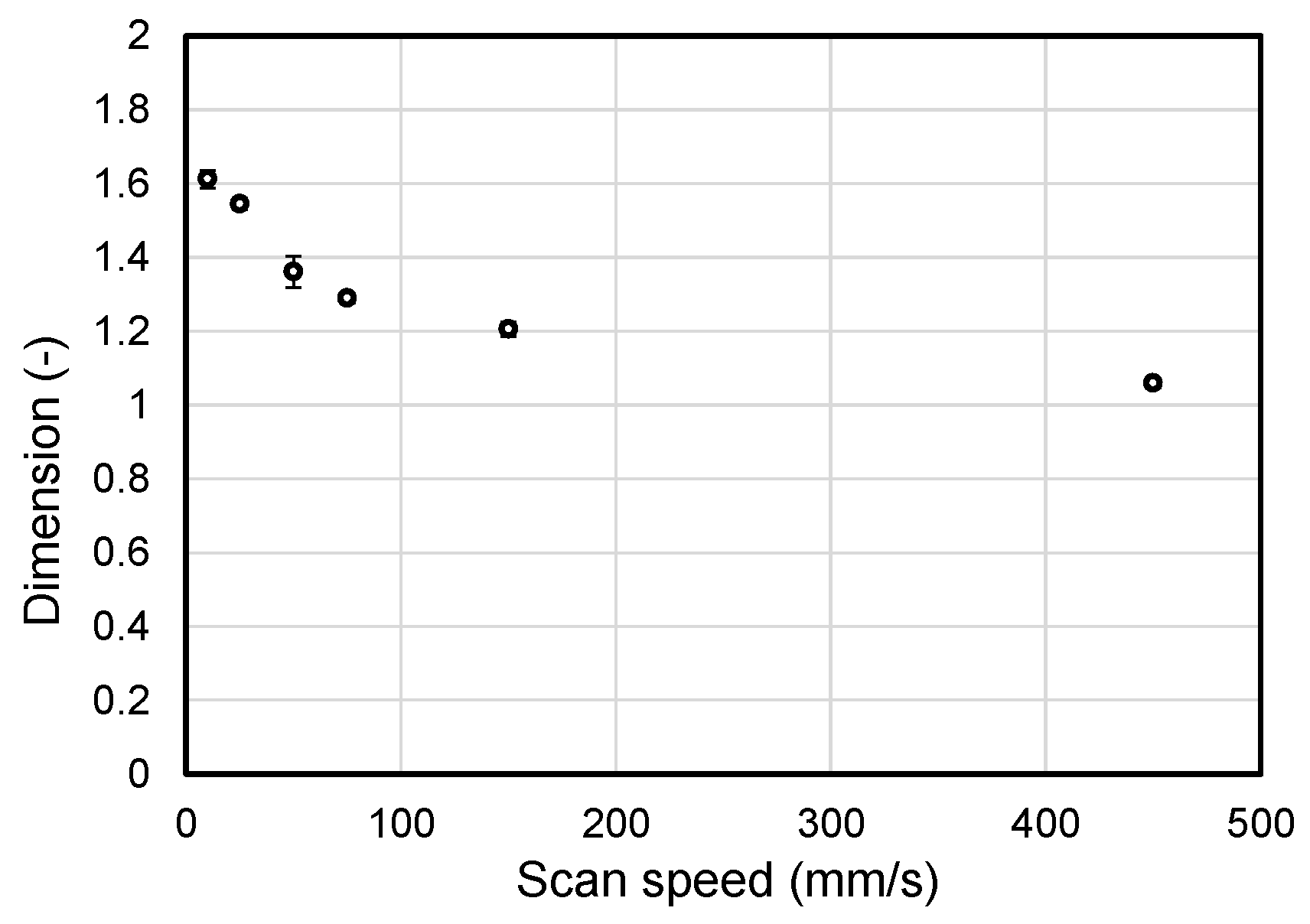

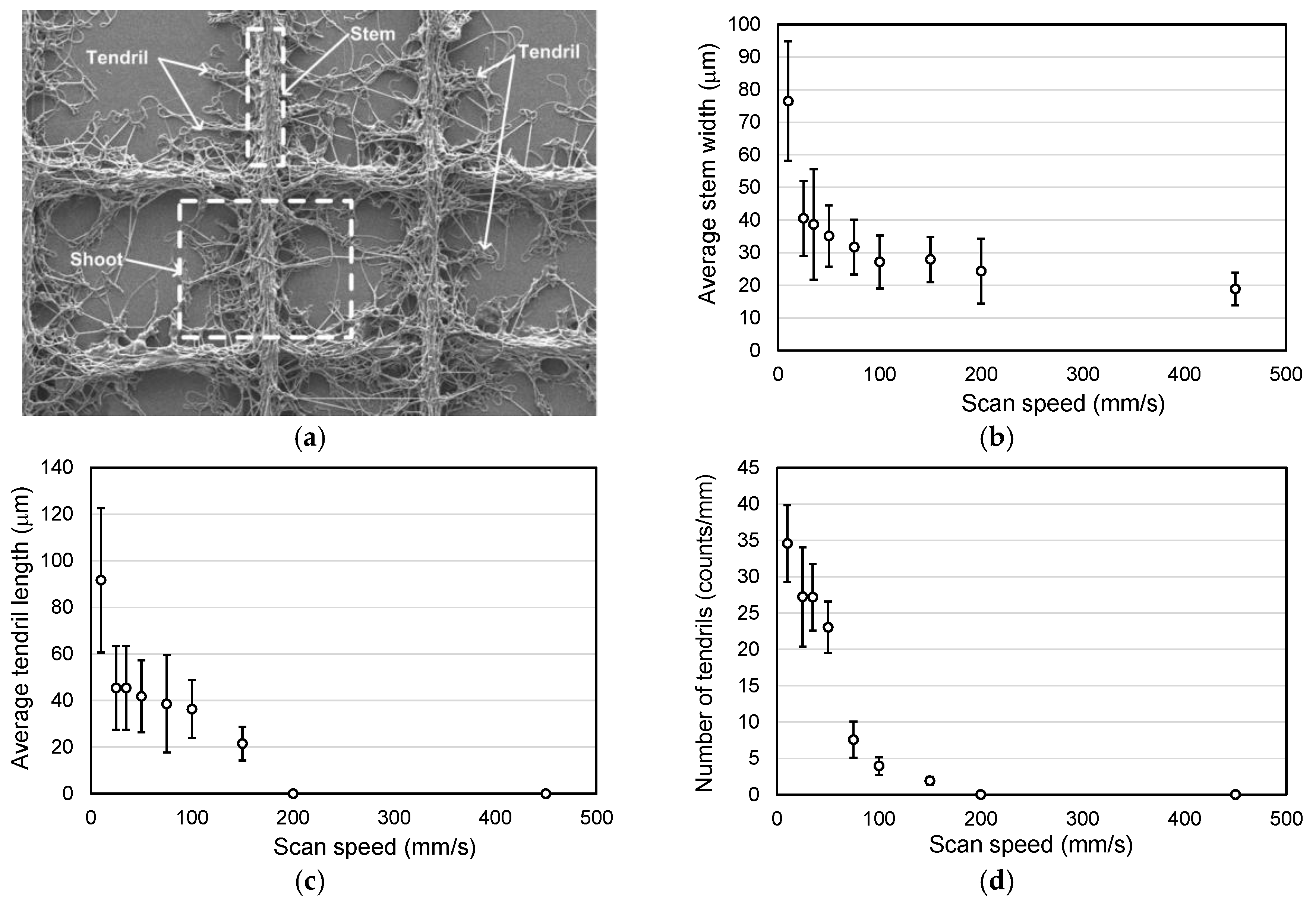

2.2. Influence of the Scan Speed of the Collector

2.3. Influence of the Relative Humidity

3. Experimental Section

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, Z.M.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Kotaki, M.; Ramakrishna, S. A review on polymer nanofibers by electrospinning and their applications in nanocomposites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2003, 63, 2223–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.M.; Khademhosseini, A.; Park, Y.; Sun, K.; Lee, S.-H. Microfluidic chip-based fabrication of PLGA microfiber scaffolds for tissue engineering. Langmuir 2008, 24, 6845–6851. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pham, Q.P.; Sharma, U.; Mikos, A.G. Electrospun poly(ε-caprolactone) microfiber and multilayer nanofiber/microfiber scaffolds: Characterization of scaffolds and measurement of cellular infiltration. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 2796–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.H.; Shin, S.J.; Park, Y.; Lee, S.H. Synthesis of cell-laden alginate hollow fibers using microfluidic chips and microvascularized tissue-engineering applications. Small 2009, 5, 1264–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sill, T.J.; von Recum, H.A. Electrospinning: Applications in drug delivery and tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 1989–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranganath, S.H.; Wang, C.-H. Biodegradable microfiber implants delivering paclitaxel for post-surgical chemotherapy against malignant glioma. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2996–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, J.E.O.; Jacoby, W.A. Microfibrous mesh coated with titanium dioxide: A self-sterilizing, self-cleaning filter. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2002, 52, 1206–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obvintseva, L.; Dmitrieva, M.; Klimuk, A.; Shepelev, A.; Kozlova, N.; Sadovskaya, N.; Tomashpol’skii, Y.A.; Avetisov, A. Action of ozone on polysulfone-based microfibrous filters. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2010, 83, 1069–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-M.; Yang, M.-B.; Lu, A.; Feng, J.-M.; Huang, R. Tensile properties of poly(ethylene terephthalate) and polyethylene in-situ microfiber reinforced composite formed via slit die extrusion and hot-stretching. Mater. Lett. 2002, 56, 756–762. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, S.-W.; Tonelli, A.E.; Hudson, S.M. Structural studies of Bombyx mori silk fibroin during regeneration from solutions and wet fiber spinning. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 1722–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuzaki, H.; Harashina, Y.; Yan, H. Highly conductive PEDOT/PSS microfibers fabricated by wet-spinning and dip-treatment in ethylene glycol. Eur. Polym. J. 2009, 45, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, J.; Shao, H.; Hu, X. Bio-inspired capillary dry spinning of regenerated silk fibroin aqueous solution. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2011, 31, 1602–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Uddin, A.J.; Aoki, K.; Gotoh, Y.; Saito, T.; Yumura, M. Fabrication of high strength PVA/SWCNT composite fibers by gel spinning. Carbon 2010, 48, 1977–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett, M.L.; Cannizzaro, C.M.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G.; Kaplan, D.L. Gel spinning of silk tubes for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 4650–4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.-H.; Choi, C.-H.; Chung, S.; Chung, Y.-M.; Lee, C.-S. Microfluidic synthesis of a cell adhesive Janus polyurethane microfiber. Lab Chip 2009, 9, 2596–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.H.; Shin, S.J.; Kim, C.B.; Kim, J.K.; Cho, Y.W.; Chung, B.G.; Lee, S.-H. Microfluidic synthesis of pure chitosan microfibers for bio-artificial liver chip. Lab Chip 2010, 10, 1328–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.; Dong, J. Direct fabrication of high-resolution three-dimensional polymeric scaffolds using electrohydrodynamic hot jet plotting. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2013, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.M.; Yang, W.; Li, L.B.; Xie, B.H.; Huang, R.; Yang, M.B. Morphology and nonisothermal crystallization of in situ microfibrillar poly(ethylene terephthalate)/polypropylene blend fabricated through slit-extrusion, hot-stretch quenching. J. Polym. Sci. Pt. B Polym. Phys. 2004, 42, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridrikh, S.V.; Yu, J.H.; Brenner, M.P.; Rutledge, G.C. Controlling the fiber diameter during electrospinning. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 90, 144502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, M.G.; Wilkes, G.L.; Colby, R.H.; Long, T.E. Correlations of solution rheology with electrospun fiber formation of linear and branched polyesters. Macromolecules 2004, 37, 1760–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Hohman, M.; Brenner, M.; Rutledge, G. Experimental characterization of electrospinning: The electrically forced jet and instabilities. Polymer 2001, 42, 09955–09967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katta, P.; Alessandro, M.; Ramsier, R.; Chase, G. Continuous electrospinning of aligned polymer nanofibers onto a wire drum collector. Nano Lett. 2004, 4, 2215–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chang, J. Patterning of electrospun fibers using electroconductive templates. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 3664–3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.J.; Kim, B.; An, T.; Lim, G. Replicable multilayered nanofibrous patterns on a flexible film. Langmuir 2010, 26, 14395–14399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, G.; Yu, J.; Qiu, Y.; Yi, X.; Lu, J.; Zhou, X.; Bai, X. Self-assembly of electrospun polymer nanofibers: A general phenomenon generating honeycomb-patterned nanofibrous structures. Langmuir 2011, 27, 4285–4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlberg, B.; Wang, T.; Liu, J. Direct photolithographic patterning of electrospun films for defined nanofibrillar microarchitectures. Langmuir 2010, 26, 2235–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, P.D.; Joergensen, N.T.; Groll, J.; Moeller, M. Patterned melt electrospun substrates for tissue engineering. Biomed. Mater. 2008, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellan, L.M.; Craighead, H. Control of an electrospinning jet using electric focusing and jet-steering fields. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2006, 24, 3179–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, S.Y.; Jang, J.; Jeong, Y.H.; Cho, D.-W. Fabrication of patterned nanofibrous mats using direct-write electrospinning. Langmuir 2012, 28, 7267–7275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishna, S.; Fujihara, K.; Teo, W.-E.; Lim, T.-C.; Ma, Z. An Introduction to Electrospinning and Nanofibers; World Scientific Pub Co. Inc: Singapore, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, M.J.; George, E.B. Fractals and the analysis of growth paths. Bull. Math. Biol. 1985, 47, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandelbrot, B.B.; Blumen, A. Fractal geometry: What is it, and what does it do? [and discussion]. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. 1989, 423, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fractalyse—Fractal Analysis Software. Available online: http://www.fractalyse.org/ (accessed on 28 January 2016).

| Parameter (Units) | Value |

|---|---|

| Polymer-solvent (concentration, wt %) | PCL-chloroform (8.8 wt %) |

| Temperature (°C) | 21–22 |

| Relative humidity (%) | 55–58 |

| Voltage (kV) | 21–24 |

| Tip-to-collector distance (mm) | 60.0 |

| Solution flow rate (mL/h) | 0.1, 0.3, 0.6 and 0.8 |

| Scan speed of collector (mm/s) | 25.0 |

| Parameter (Units) | Value |

|---|---|

| Polymer-solvent (concentration, wt %) | PCL-chloroform (8.8 wt %) |

| Temperature (°C) | 20–21 |

| Relative humidity (%) | 56–58 |

| Voltage (kV) | 21 |

| Tip-to-collector distance (mm) | 60.0 |

| Solution flow rate (mL/h) | 0.6 |

| Scan speed of collector (mm/s) | 10–450 |

| Parameter (Units) | Value |

|---|---|

| Polymer-solvent (concentration, wt %) | PCL-chloroform (8.8 wt %) |

| Temperature (°C) | 20–21 |

| Voltage (kV) | 21 |

| Tip-to-collector distance (mm) | 60.0 |

| Solution flow rate (mL/h) | 0.6 |

| Scan speed of collector (mm/s) | 20 |

| Relative humidity (%) | 51 and 60 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, Y.H.; Lee, J. Fabrication of Microfiber Patterns with Ivy Shoot-Like Geometries Using Improved Electrospinning. Materials 2016, 9, 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9040266

Jeong YH, Lee J. Fabrication of Microfiber Patterns with Ivy Shoot-Like Geometries Using Improved Electrospinning. Materials. 2016; 9(4):266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9040266

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Young Hun, and Jongwan Lee. 2016. "Fabrication of Microfiber Patterns with Ivy Shoot-Like Geometries Using Improved Electrospinning" Materials 9, no. 4: 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9040266

APA StyleJeong, Y. H., & Lee, J. (2016). Fabrication of Microfiber Patterns with Ivy Shoot-Like Geometries Using Improved Electrospinning. Materials, 9(4), 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9040266