Atomic-Scale Insights into Alloying-Induced Interfacial Stability, Adhesion, and Electronic Structure of Mg/Al3Y Interfaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Section

3. Results and Discussion

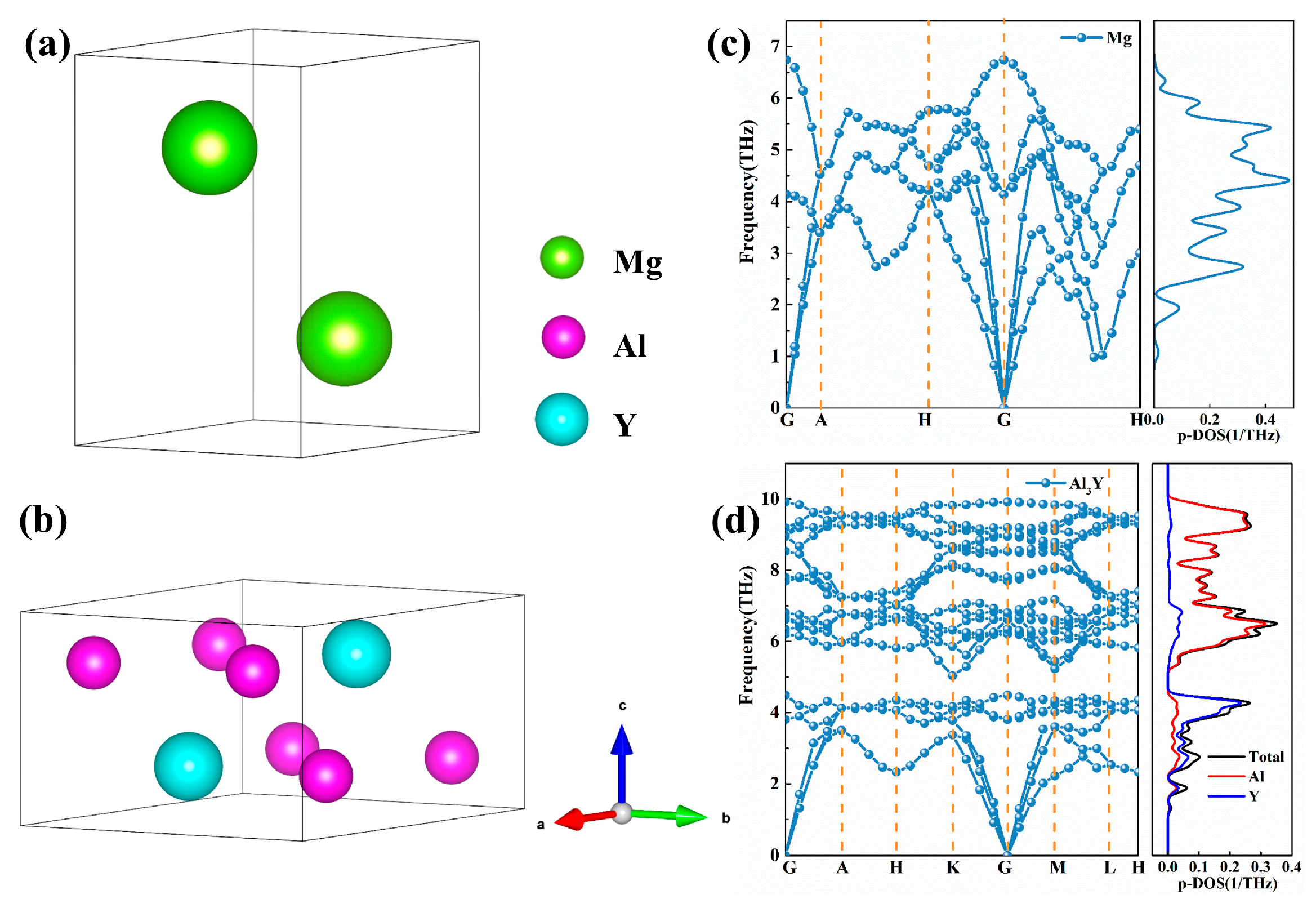

3.1. Bulk and Surface Properties

3.2. Properties of the Mg/Al3Y Interface

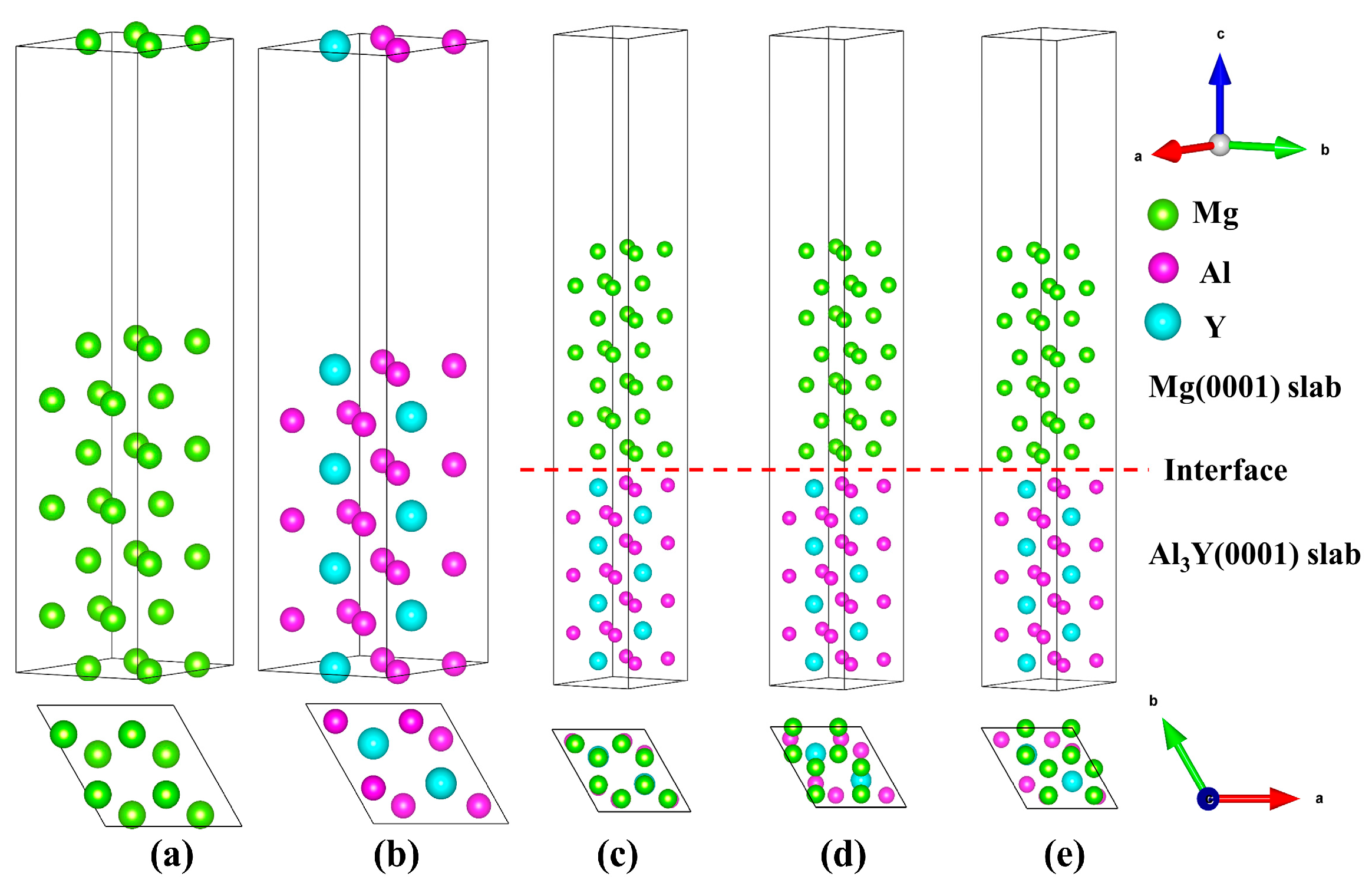

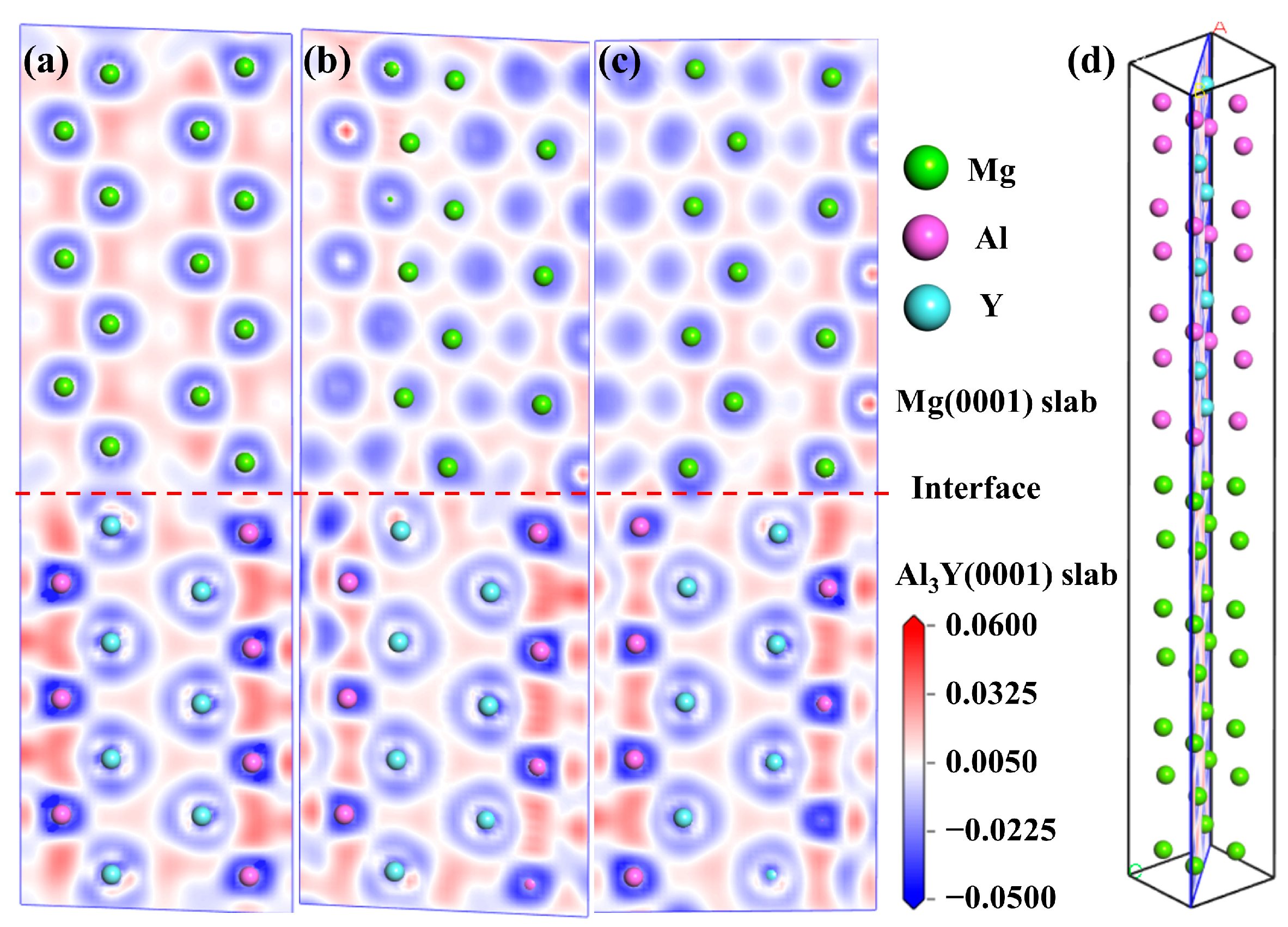

3.2.1. Interfacial Configuration

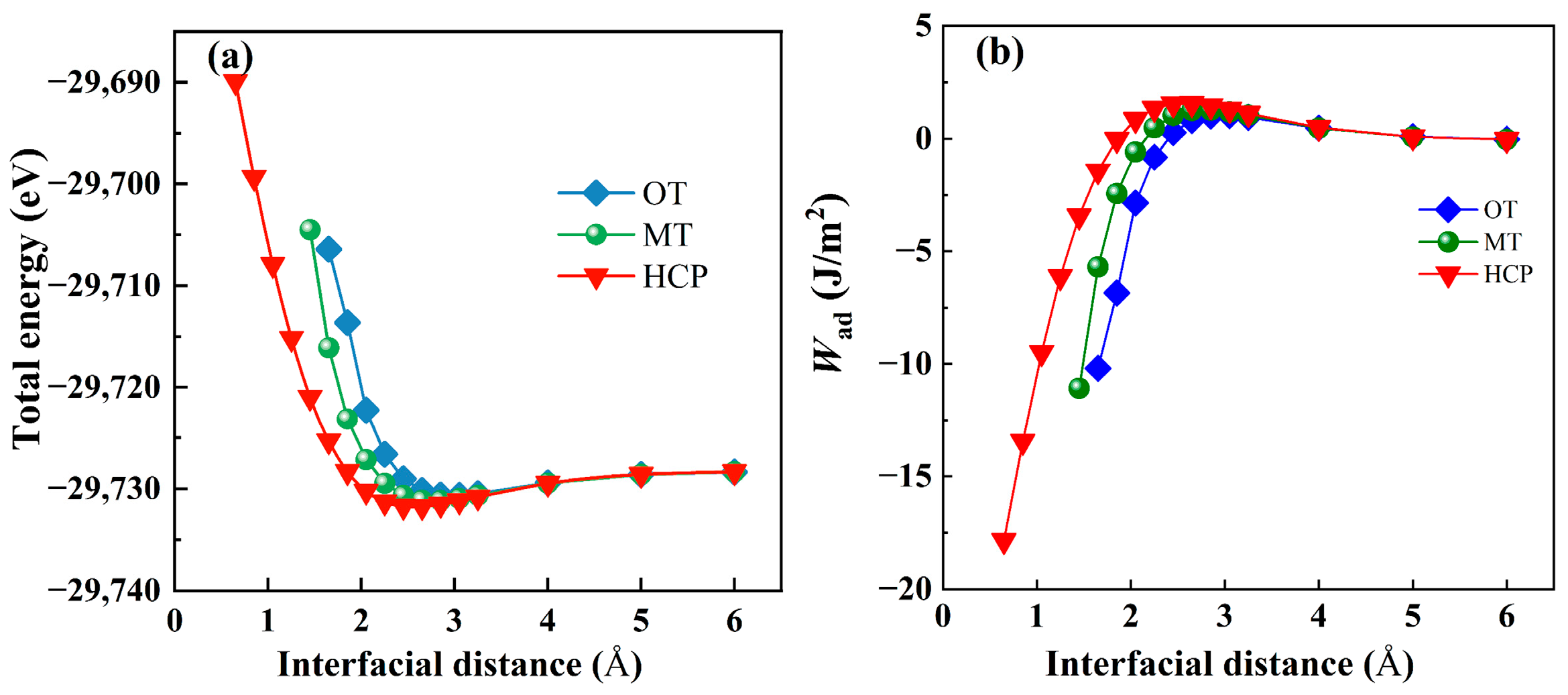

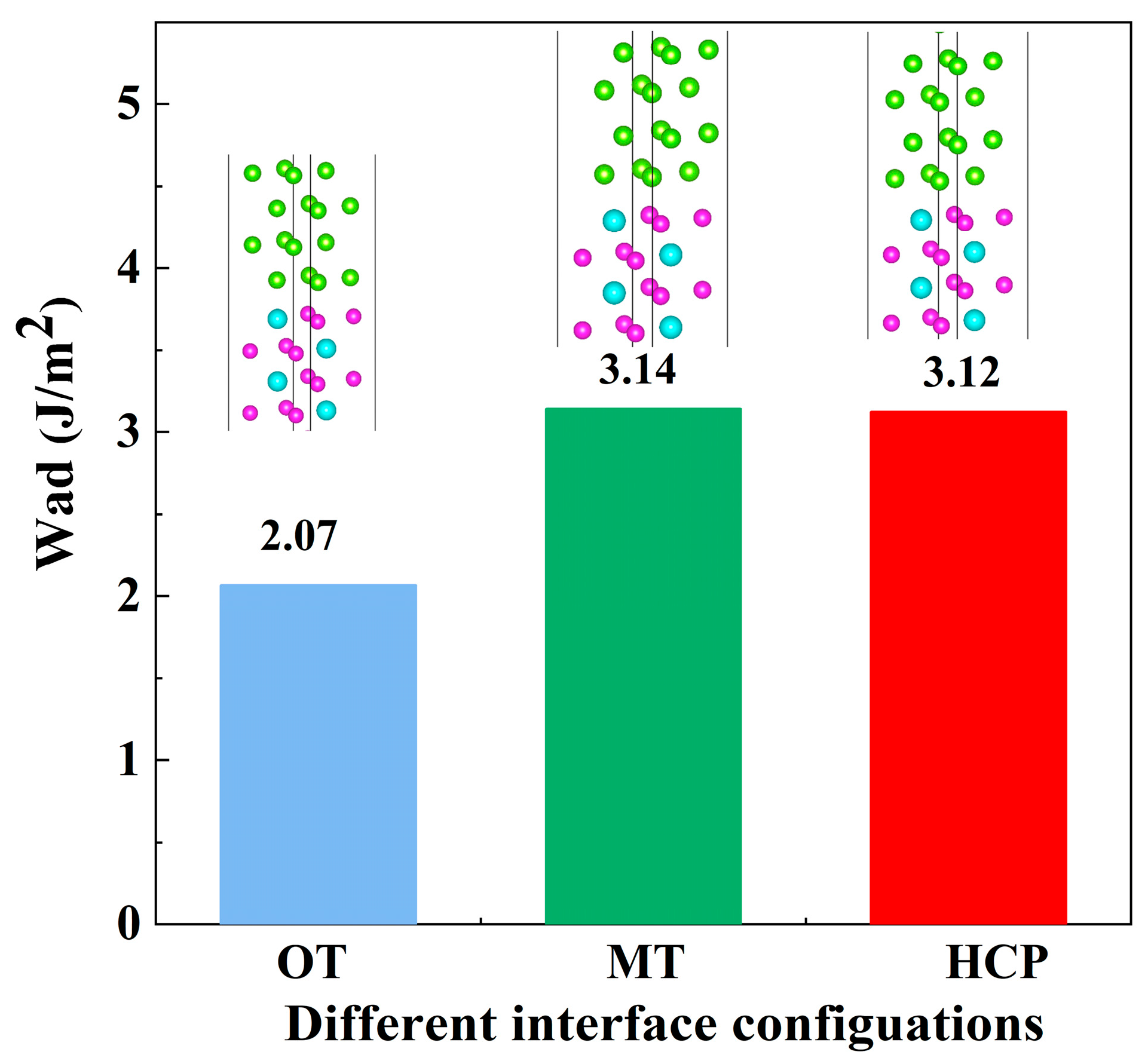

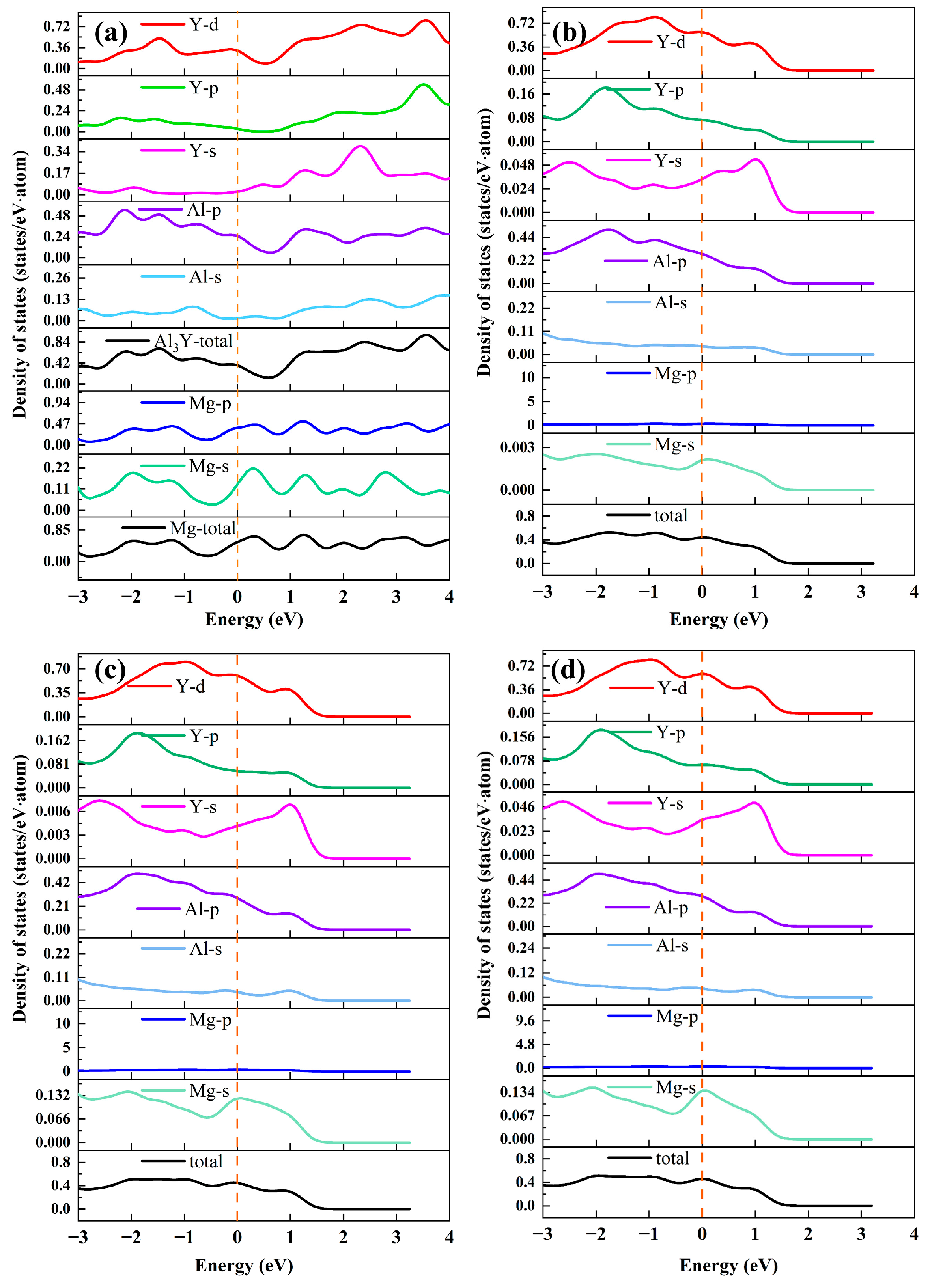

3.2.2. Interfacial Stabilities and Electronic Structure

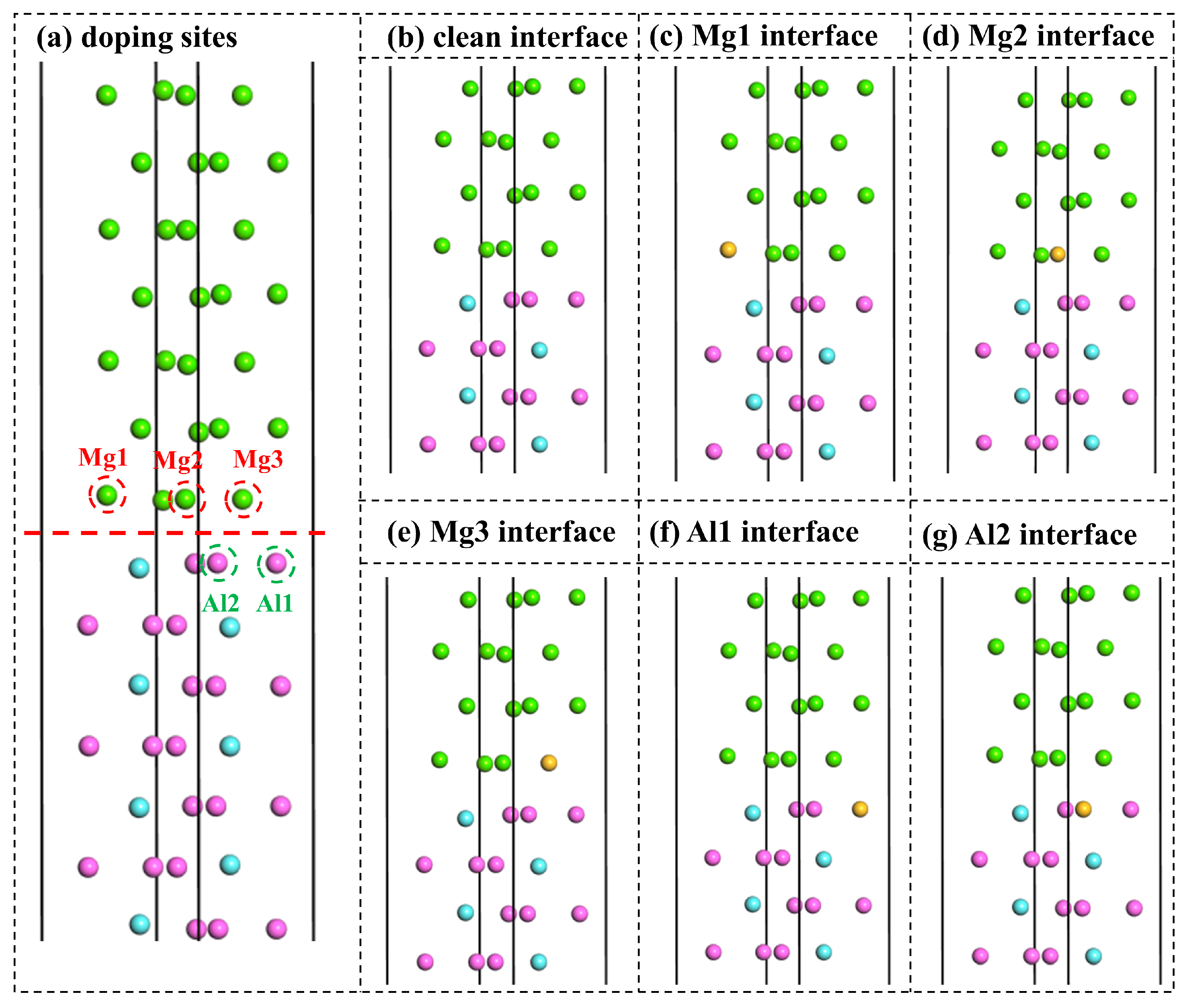

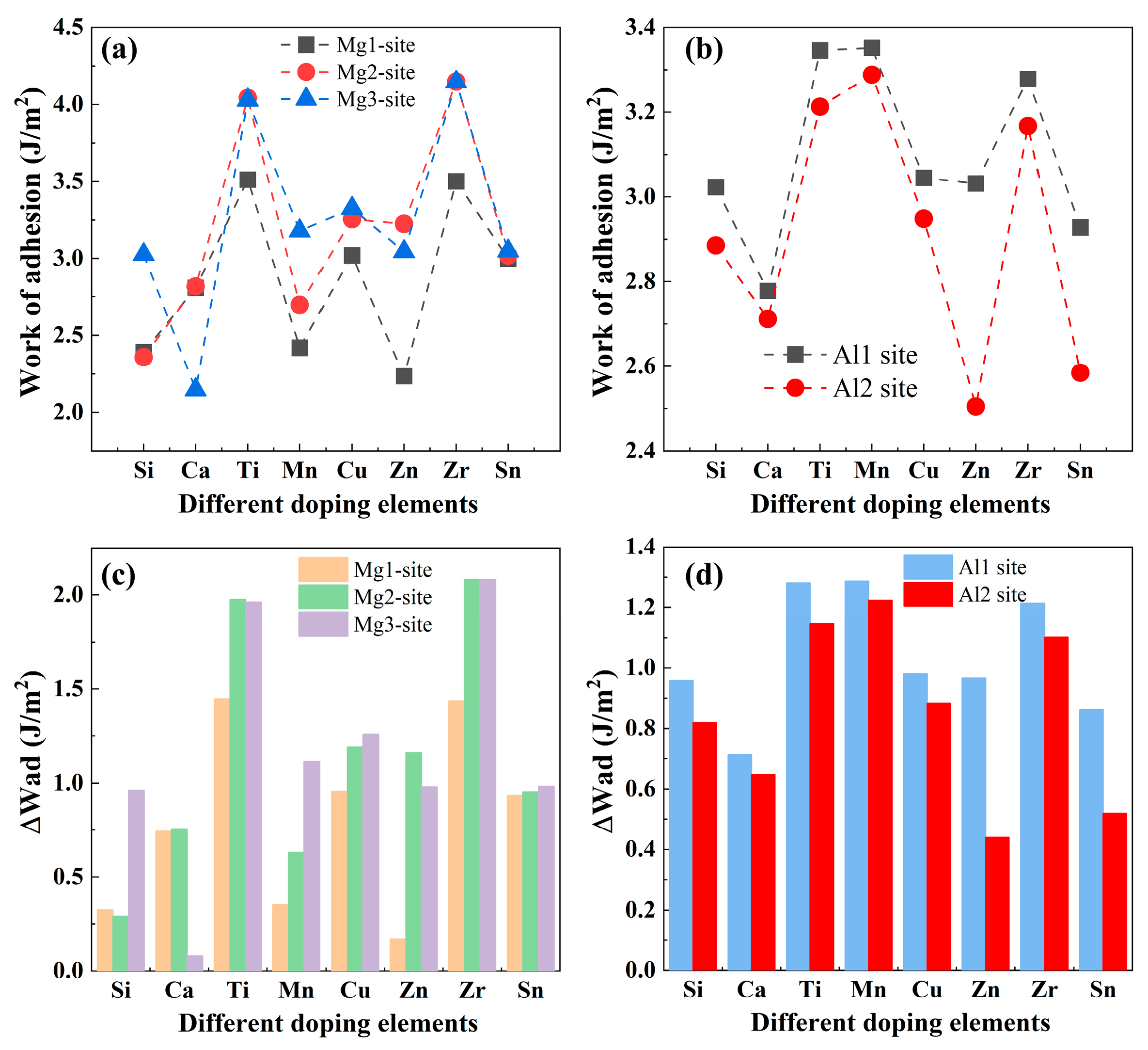

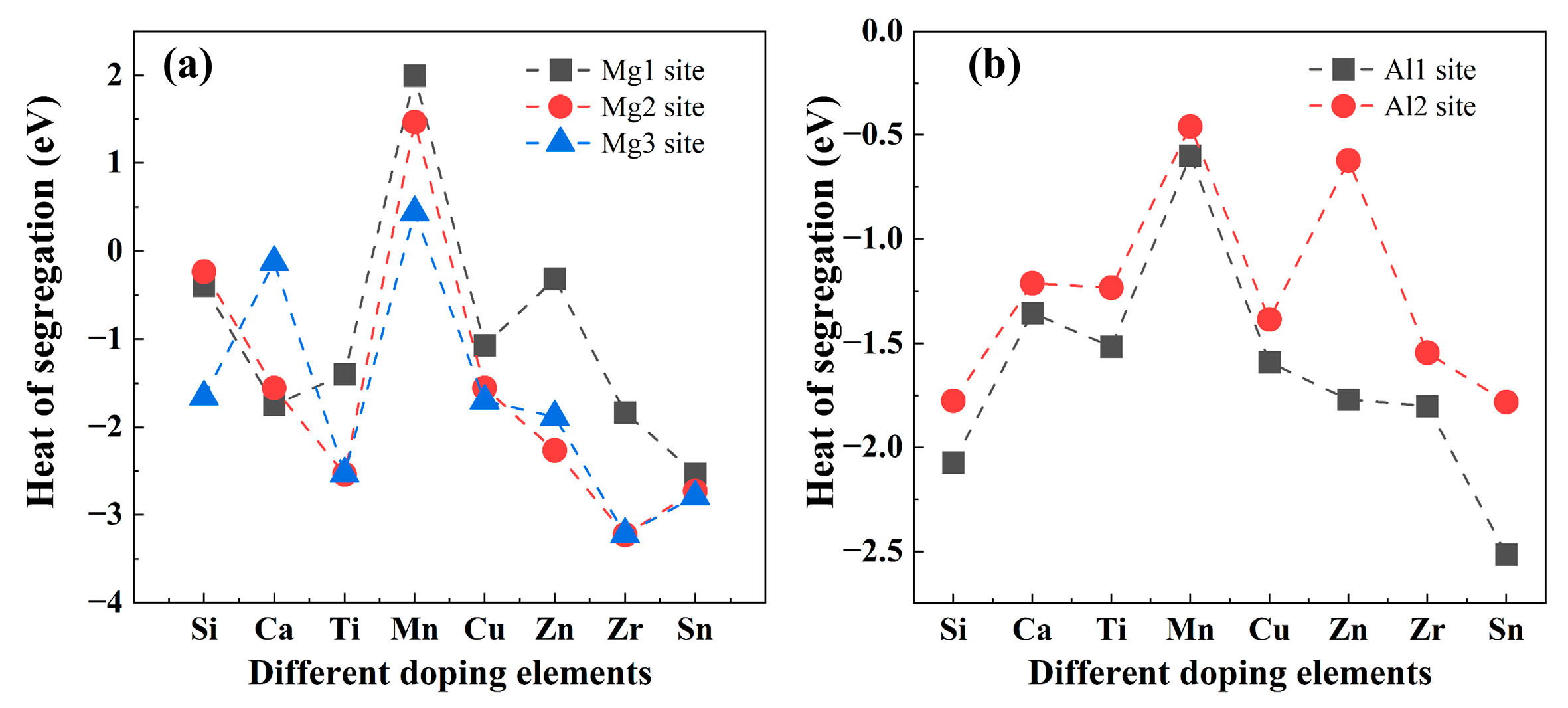

3.2.3. Interfacial Segregation and Adhesion Enhancement

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, W.; Zhao, D.; Huang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Xu, X.; Zhang, H.; Huang, G. Research progress of heterogeneous structure magnesium alloys: A review. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 12, 2147–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; He, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, L.; Jiang, S.; Jia, N. Achieving excellent strength-ductility synergy in orientation-heterostructured Mg-Y alloy via element segregation-assisted pinning of twin boundary. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2026, 248, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Wan, H.; Ding, Z.; Chen, Y.; Pan, F. Tailoring hydrogen diffusion pathways in Mg-Ni alloys through Gd addition: A combined experimental and computational study. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 502, 157767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherian, Z.; Shahed Gharahshiran, V.; Wei, X.; Khataee, A.; Yoon, Y.; Orooji, Y. Revisiting the mitigation of coke formation: Synergism between support & promoters’ role toward robust yield in the CO2 reformation of methane. Nano Mater. Sci. 2024, 6, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Chen, X.; Xiong, X.; Li, K.; Tan, J.; Yang, Y.; Peng, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, D.; Pan, F. Research advances of magnesium and magnesium alloys globally in 2024. J. Magnes. Alloys 2025, 13, 4689–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Tan, J.; Geng, T.; Wang, H.; Shi, H.; Lin, Y.; Bin, J.; Eckert, J. Advances in high-strength and high-thermal conductivity cast magnesium alloys: Strategies for property optimization. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1029, 180843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, M.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Tan, J.; Chen, X.; Pan, F. Probing the mechanical properties and interfacial bonding mechanism of AM60 alloy reinforced with co-addition of Si3N4 and Ti particles. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 941, 148625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, H.; Sheng, P.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Guo, S.; Zhao, D. An overview of RE-Mg-based alloys for hydrogen storage: Structure, properties, progresses and perspectives. J. Magnes. Alloys 2025, 13, 41–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, N.; Zhao, L.; Yan, H.; Liu, B.; Mao, Y.; Shan, Z.; Chen, R. Texture tailoring and microstructure refinement induced by {11−21} and {10−12} twinning in an extruded Mg-Gd alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 966, 171590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Feng, L.; Wang, S.; Ji, G.; Addad, A.; Yang, H.; Nyberg, E.A.; Ji, S. On the exceptional creep resistance in a die-cast Gd-containing Mg alloy with Al addition. Acta Mater. 2022, 232, 117957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Y.; Ouyang, L.; Cui, Y.; Bian, H.; Li, Q.; Chiba, A. Grain refinement and weak-textured structures based on the dynamic recrystallization of Mg–9.80Gd–3.78Y–1.12Sm–0.48Zr alloy. J. Magnes. Alloys 2021, 9, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Dong, Z.; Jiang, B.; Wang, L.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, A.; Song, J.; Zhang, D.; Vitos, L. Low thermal expansion in conjunction with improved mechanical properties achieved in Mg-Gd solid solutions. Mater. Des. 2025, 251, 113685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liu, Y.; Han, Y.; Wan, Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, Z. Microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of Mg−Gd−Zn alloy with and without LPSO phase processed by multi-directional forging. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2025, 35, 1075–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, M.; Zhan, Y.; Ling, M.; Wei, S.; Liu, Y.; Du, Y. First-principles study on the crystal, electronic structure and mechanical properties of hexagonal Al3RE (RE = La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Gd) intermetallic compounds. Solid State Commun. 2011, 151, 1135–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Gao, K.; Gao, C.; Ding, Y.; Xiong, X.; Wu, X.; Huang, H.; Wen, S.; Nie, Z.; Zhang, Q. Hardness and Young’s modulus of Al3Yb single crystal studied by nano indentation. Intermetallics 2020, 127, 106980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Bian, X.; Si, P.; Zhou, J.K.; Lin, T.; Jia, Y. Crystallization behavior of novel amorphous Al85Mg10Ce5 alloy. Phys. Lett. A 2004, 327, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Jiang, B.; Li, X.; Yang, Q.; Dong, H.; Xia, X.; Pan, F. The formation of intermetallic compounds during interdiffusion of Mg–Al/Mg–Ce diffusion couples. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 619, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiahong, D.; Hongmei, X.; Bin, J.; Cheng, P.; Zhongtao, J.; Qingshan, Y.; Fusheng, P. Interfacial Reaction Between Mg-40Al and Mg-20Ce Using Liquid-Solid Diffusion Couples. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2018, 47, 2042–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wen, J.C.; Zhang, X.Y.; Huang, Y.C. A comparative study on heterogeneous nucleation and mechanical properties of the fcc-Al/L1(2)-Al(3)M (M = Sc, Ti, V, Y, Zr, Nb) interface from first-principles calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 4718–4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Ma, T.; Li, Y.; Ren, Y.; Liu, W. Stabilities, mechanical and thermodynamic properties of Al–RE intermetallics: A first-principles study. J. Rare Earths 2022, 40, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.-K.; Wang, H.-C.; Shi, T.-T.; Tian, X.; Tang, B.-Y. Thermal properties and thermoelasticity of L12 ordered Al3RE (RE=Er, Tm, Yb, Lu) phases: A first-principles study. Mater. Des. 2016, 102, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Qiao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Jang, J.; Ramamurty, U. Multimodality of critical strength for incipient plasticity in L12- precipitated (CoCrNi)94Al3Ti3 medium-entropy alloy: Coherent interface-facilitated dislocation nucleation. Acta Mater. 2025, 288, 120826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, T.; Lu, G.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.Y.; Luo, Y.; Li, J. Interactions of Re and hydrogen at γ/γ′ interfaces enhanced hydrogen-embrittlement resistance of Re-optimized Ni-based superalloy. Mater. Res. Lett. 2024, 12, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X. Ab-Initio Studies of the Micromechanics and Interfacial Behavior of Al3Y|fcc-Al. Metals 2022, 12, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dalen, M.E.; Karnesky, R.A.; Cabotaje, J.R.; Dunand, D.C.; Seidman, D.N. Erbium and ytterbium solubilities and diffusivities in aluminum as determined by nanoscale characterization of precipitates. Acta Mater. 2009, 57, 4081–4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Quan, G.F.; Ji, B.; Wan, Y.F.; Zhou, H.; Zheng, J.; Yin, D.D. Effect of Y content and equal channel angular pressing on the microstructure, texture and mechanical property of extruded Mg-Y alloys. J. Magnes. Alloys 2022, 10, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.Z.; Qiao, X.G.; Qin, S.H.; Chi, Y.Q.; Zheng, M.Y. Improved strength in wrought Mg-Y-Ni alloys by adjusting the block-shaped LPSO phase and plate-shaped gamma’ phase. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 831, 142198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-Y.; Euh, K.; Son, H.-W. Unraveling mechanism of structural transformation from D022-Al3Y to L12-Al3(Y, Zr) phase by inward diffusion of Zr and anti-phase boundary in the Al-Zr-Y alloy at elevated temperature. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2026, 245, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Ji, Y.; Yao, C.; Lv, H.; Liu, X.; Jiang, Z.; Ren, X.; Xia, Y.; Dong, C. Effect of yttrium addition and Al3Y phase dissolution on corrosion behavior of Al-Mg-Zn alloys. Corros. Sci. 2025, 256, 113205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segall, M.D.; Lindan, P.J.D.; Probert, M.J.; Pickard, C.J.; Hasnip, P.J.; Clark, S.J.; Payne, M.C. First-principles simulation: Ideas, illustrations and the CASTEP code. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2002, 14, 2717–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderbilt, D. Soft self-consistent pseudopotentials in a generalized eigenvalue formalism. Phys. Rev. B Condened Matter 1990, 41, 7892–7895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, J.D.; Zerner, M.C. A Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno optimization procedure for molecular geometries. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1985, 122, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Ruzsinszky, A.; Csonka, G.I.; Vydrov, O.A.; Scuseria, G.E.; Constantin, L.A.; Zhou, X.; Burke, K. Restoring the density-gradient expansion for exchange in solids and surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 136406, Erratum in Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 039902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Dong, Q.; Tan, J.; Chen, X.; Jiang, B.; Pan, F.; Eckert, J. Probing the stability, adhesion strength, and fracture mechanism of Mg/Al2Y interfaces via first-principles calculations. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tian, W.; Dong, Q.; Wang, H.; Tan, J.; Chen, X.; Zheng, K.; Pan, F. A First-principles study on the adhesion strength, interfacial stability, and electronic properties of Mg/Mg2Y interface. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 2023, 37, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Xie, Y. Ab initiothermodynamics of the hcp metals Mg, Ti, and Zr. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 75, 174117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yin, X.; Feng, K.; Xu, R. First-principles calculations on Mg/TiB2 interfaces. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2018, 149, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, M.; Huang, K. Dynamical Theory of Crystal Lattices; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilyev, D. Thermal expansion anisotropy of Fe23Mo16 and Fe7Mo6 mu-phases predicted using first-principles calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 3482–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Sun, J.; Li, S.; Meng, Y.; Zheng, H.; Yin, Z.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Heterogeneous nucleation mechanisms in Mg(0001)/Al3BC(0001) interfaces: Insights for advanced Mg-based composites. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 46, 104040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Z. Theoretical prediction on interfacial bonding and strengthening mechanism of polymorphic ZrO2/Fe interfaces. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2025, 699, 416871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, G.; Panwisawas, C.; Teng, X.; An, R.; Cao, J.; Huang, Y.; Dong, Z.; Leng, X. Uncovering the fracture mechanism of Laves (111)/ Ni6Nb7 (0001) interfaces by first-principles calculations. Acta Mater. 2024, 281, 120426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Yuan, Z.; Rong, J.; Feng, J.; Muzammil, I.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhan, Z. DHQ-graphene: A novel two-dimensional defective graphene for corrosion-resistant coating. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 8967–8974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lv, H.; Chen, T.; Tong, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Tan, J.; Chen, X.; Pan, F. Probing the effect of alloying elements on the interfacial segregation behavior and electronic properties of Mg/Ti interface via first-principles calculations. Molecules 2024, 29, 4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Zhang, P.; Tang, J.; Wang, L.; Deng, L.; Wu, Y.; Deng, H.; Hu, W.; Zhang, X. Segregation of alloying elements at the TiC/V interface: A first-principles study. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2023, 35, 101452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butrim, V.N.; Razumovskii, I.M.; Beresnev, A.G.; Kartsev, A.; Razumovskiy, V.I.; Trushnikova, A.S. Effect of alloying elements and impurity (N) on bulk and grain boundary cohesion in Cr-base alloys. Adv. Mater. Res. 2015, 1119, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Lyu, G.; Wang, K.; Gao, P.; Qian, P. First-principles study of the effect of solute co-segregation on Y {101¯1} twin boundary. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2026, 249, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Xing, Y.; Ning, Y.; Ding, L.; Ehlers, F.J.H.; Hao, L.; Liu, Q. Density gradient segregation of Cu at the Si2Hf/Al interface in an Al-Si-Cu-Hf alloy. Scr. Mater. 2023, 222, 115022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, X.; Wei, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, M. The segregation behavior of elements at the Ti/TiFe coherent interface: First-principles calculation. Surf. Interfaces 2022, 34, 102321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouadah, O.; Merad, G.; Abdelkader, H.S. Energetic segregation of B, C, N, O at the γ-TiAl/α2-Ti3Al interface via DFT approach. Vacuum 2021, 186, 110045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Chong, X.; Li, Z.; Feng, J.; Jiang, Y. Strain-stiffening of chemical bonding enhance strength and fracture toughness of the interface of Fe2B/Fe in situ composite. Mater. Charact. 2024, 207, 113575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Method | a (Å) | c (Å) | c/a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg | GGA + PBEsol | 3.18 | 5.32 | 1.67 |

| Before relax | 3.17 | 5.14 | 1.62 | |

| Exp. [37] | 3.209 | 5.211 | ||

| GGA + PBE [38] | 3.221 | 5.172 | ||

| LDA [38] | 3.159 | 5.073 | ||

| Al3Y | GGA + PBEsol (this work) | 6.28 | 4.60 | 0.73 |

| Before relax | 6.27 | 4.59 | 0.73 |

| Species | Method | C11 | C33 | C44 | C12 | C13 | B | G | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg | GGA + PBEsol | 55.44 | 71.16 | 19.89 | 30.73 | 23.87 | 37.60 | 16.79 | 43.85 |

| Exp. [37] | 35.4 | ||||||||

| GGA + PBE [38] | 35.6 | ||||||||

| LDA [38] | 43.9 | ||||||||

| Al3Y | GGA + PBEsol | 161.25 | 186.57 | 71.01 | 65.33 | 24.15 | 79.36 | 62.35 | 148.23 |

| Species | Wad (J/m2) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Mg/Al3Y-OT | 2.07 | This work |

| Mg/Al3Y-MT | 3.14 | This work |

| Mg/Al3Y-HCP | 3.12 | This work |

| Mg/Al2Y-Al-OT | 1.49 | [35] |

| Mg/Al2Y-Al-MT | 1.63 | [35] |

| Mg/Al2Y-Al-HCP | 1.56 | [35] |

| Mg/Al2Y-Y-OT | 1.19 | [35] |

| Mg/Al2Y-Y-MT | 1.54 | [35] |

| Mg/Al2Y-Y-HCP | 1.68 | [35] |

| Mg/Mg2Y-Mg1-OT | 0.94 | [36] |

| Mg/Mg2Y-Mg1-MT | 0.43 | [36] |

| Mg/Mg2Y-Mg1-HCP | 1.99 | [36] |

| Mg/Mg2Y-Mg2-OT | 1.80 | [36] |

| Mg/Mg2Y-Mg2-MT | 1.84 | [36] |

| Mg/Mg2Y-Mg2-HCP | 1.82 | [36] |

| Mg/Mg2Y-Y-OT | 1.99 | [36] |

| Mg/Mg2Y-Y-MT | 2.36 | [36] |

| Mg/Mg2Y-Y-HCP | 2.38 | [36] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, Y.; Gao, L.; Hou, Q.; Tan, J.; Ding, Z. Atomic-Scale Insights into Alloying-Induced Interfacial Stability, Adhesion, and Electronic Structure of Mg/Al3Y Interfaces. Materials 2026, 19, 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030562

Zhou Y, Gao L, Hou Q, Tan J, Ding Z. Atomic-Scale Insights into Alloying-Induced Interfacial Stability, Adhesion, and Electronic Structure of Mg/Al3Y Interfaces. Materials. 2026; 19(3):562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030562

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Yunxuan, Liangjuan Gao, Quanhui Hou, Jun Tan, and Zhao Ding. 2026. "Atomic-Scale Insights into Alloying-Induced Interfacial Stability, Adhesion, and Electronic Structure of Mg/Al3Y Interfaces" Materials 19, no. 3: 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030562

APA StyleZhou, Y., Gao, L., Hou, Q., Tan, J., & Ding, Z. (2026). Atomic-Scale Insights into Alloying-Induced Interfacial Stability, Adhesion, and Electronic Structure of Mg/Al3Y Interfaces. Materials, 19(3), 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030562