Localized Induction Heating for Crack Healing of AISI 1020 Steel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wire-Cut Slit of AISI 1020 Steel

2.2. Repetitive Bending Crack of AISI 1020 Steel

2.3. Induction Heating

2.4. Sample Characterization

2.5. Numerical Simulations

3. Results

3.1. Wire-Cut Slit Changes After Induction Heating

3.2. Fine Cracks from Repetitive Bending Changes After Induction Heating

4. Discussion

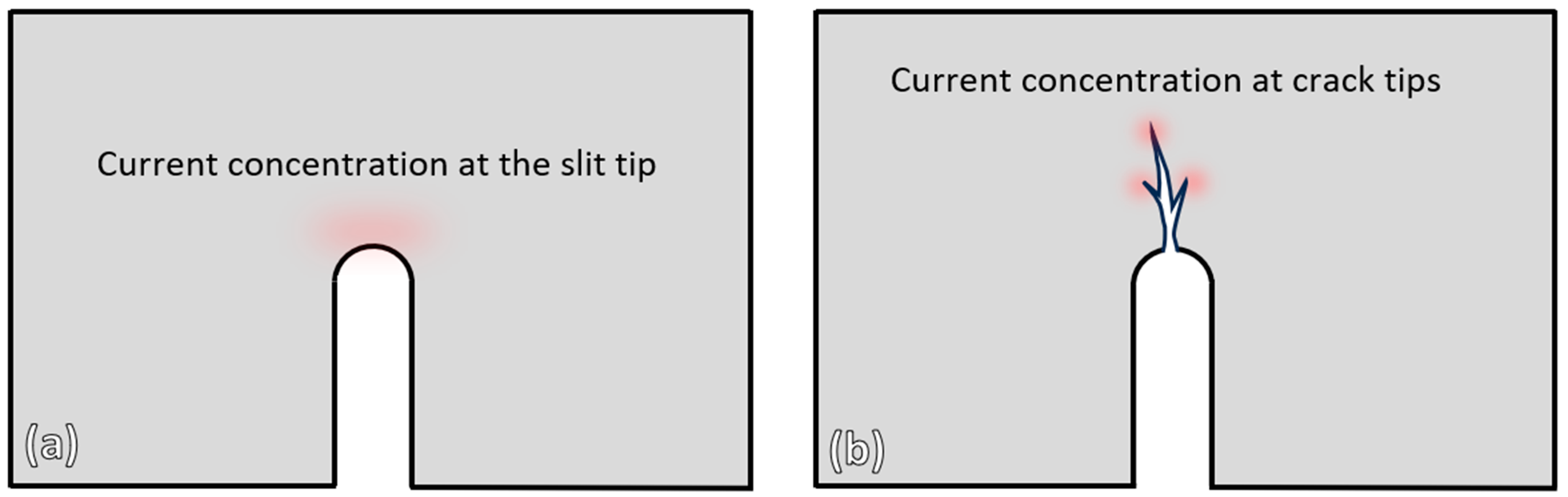

4.1. Detouring and Crowding of Eddy Current

4.2. Selective and Localized Healing of Cracks in Induction Heating

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Current crowding occurred at the slit tip of the wire-cut slit sample and at the fine crack tips of the repetitive-bent sample. This resulted in localized melting in the wire-cut slit sample and successful crack healing of fine cracks in the repetitive-bent sample.

- (2)

- Current detouring and crowding of induction heating are useful for crack-healing applications, as cracks within the material can be automatically located and treated without significantly affecting the surrounding bulk material.

- (3)

- Localized induction heating using a pancake coil has the advantage of providing a non-singular current flow direction within the material, enhancing the effectiveness of crack healing. The pancake coil configuration also offers the flexibility to only treat a specific localized region within a component.

- (4)

- Crack healing by induction heating can effectively occur if the crack is located within the skin depth and if the crack width is not too large for the induction power used. Induction heating is highly suitable for crack-healing applications due to its ability to selectively locate and treat cracks; however, it is primarily effective for fine surface cracks.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sheng, Y.; Hua, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, X.; Chen, L.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Berndt, C.C.; Li, W. Application of high-density electropulsing to improve the performance of metallic materials: Mechanisms, microstructure and properties. Materials 2018, 11, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Wang, C.; Chen, P.; Xu, Z.; Cheng, L.; Guo, B.; Shan, D. Investigation of electrically-assisted rolling process of corrugated surface microstructure with T2 copper foil. Materials 2019, 12, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okazaki, K.; Kagawa, M.; Conrad, H. An evaluation of the contributions of skin, pinch and heating effects to the electroplastic effect in titanium. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1980, 45, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, H.; Karam, N.; Mannan, S. Effect of electric current pulses on the recrystallization of copper. Scr. Met. 1983, 17, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, H.; Karam, N.; Mannan, S. Effect of prior cold work on the influence of electric-current pulses on the recrystallization of copper. Scr. Met. 1984, 18, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanov, G.; Babutskii, A. Stress relaxation in steel caused by a high-density current. Strength Mater. 1993, 25, 697–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanov, G.; Babutskii, A. Effect of electric current on stress relaxation in metal. Strength Mater. 1996, 28, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Qin, R.; Xiao, S.; He, G.; Zhou, B. Reversing effect of electropulsing on damage of 1045 steel. J. Mater. Res. 2000, 15, 1056–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Qiao, D.; He, G.; Guo, J. Improvement of mechanical properties in a saw blade by electropulsing treatment. Mater. Lett. 2003, 57, 1566–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Guo, J.; Gao, M.; He, G. Crack healing in a steel by using electropulsing technique. Mater. Lett. 2004, 58, 1732–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Wang, Z.J. Microcrack healing and local recrystallization in pre-deformed sheet by high density electropulsing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 490, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Wang, Z.J.; He, X.D.; Duan, J. Self-healing of damage inside metals triggered by electropulsing stimuli. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Xu, W.; Gao, B.; Tian, G.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yin, Y.; Chen, J. Pattern deep region learning for crack detection in thermography diagnosis system. Metals 2018, 8, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repelianto, A.S.; Kasai, N.; Sekino, K.; Matsunaga, M. A uniform eddy current probe with a double-excitation coil for flaw detection on aluminium plates. Metals 2019, 9, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Xu, W.; Guo, B.; Shan, D.; Zhang, J. Healing of fatigue crack in 1045 steel by using eddy current treatment. Materials 2016, 9, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Xu, W.; Chen, Y.; Guo, B.; Shan, D. Restoration of fatigue damage in steel tube by eddy current treatment. Int. J. Fatigue 2019, 124, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Yang, C.; Yu, H.; Jin, X.; Guo, B.; Shan, D. Microcrack healing in non-ferrous metal tubes through eddy current pulse treatment. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Yang, C.; Yu, H.; Jin, X.; Yang, G.; Shan, D.; Guo, B. Combination of eddy current and heat treatment for crack healing and mechanical-property improvement in magnesium alloy tube. J. Magnes. Alloys 2021, 9, 1768–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprilia, A.; Tan, J.L.; Yang, Y.; Tan, S.C.; Zhou, W. Induction brazing for rapid localized repair of Inconel 718. Metals 2021, 11, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Aprilia, A.; Tan, S.C.; Zhou, W. Rapid post processing of cold sprayed Inconel 625 by induction heating. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 872, 144955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprilia, A.; Wu, K.; Yang, Y.; Neo, R.G.; Ong, A.; Zhai, W.; Zhou, W. Rapid densification of cold-sprayed Ti-6Al-4V coatings via induction heating. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 39, 6096–6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudney, V.; Loveless, D.; Cook, R.L. Handbook of Induction Heating, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penalva-Salinas, M.; Llopis-Castelló, D.; Alonso-Troyano, C.; Garcia, A. Induction heating optimization for efficient self-healing in asphalt concrete. Materials 2024, 17, 5602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, A.; Tan, J.L.; Yang, Y.; Aprilia, A.; Chia, N.; Williams, P.; Jones, M.; Zhou, W. Misorientation and dislocation evolution in rapid residual stress relaxation by electropulsing. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 209, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, H.; Deng, D.; Hao, S.; Iqbal, A. Numerical calculation and experimental research on crack arrest by detour effect and joule heating of high pulsed current in remanufacturing. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2014, 27, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Jiang, T.; Huang, J.; Peng, L.; Lai, X.; Fu, M.W. Electroplasticity in electrically-assisted forming: Process phenomena, performances and modelling. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2022, 175, 103871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AISI 1020 Steel, Cold Rolled. Available online: https://www.matweb.com/search/DataSheet.aspx?MatGUID=10b74ebc27344380ab16b1b69f1cffbb (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- What Is Mild Steel? Applications & Uses. Available online: https://us.misumi-ec.com/blog/what-is-mild-steel/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

| C | Mn | Si | Ni | Cu | P | S | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.009 | 0.0042 | Bal. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Aprilia, A.; Ling, Z.; Gill, V.; Chia, N.; Jones, M.A.; Williams, P.E.; Zhou, W. Localized Induction Heating for Crack Healing of AISI 1020 Steel. Materials 2026, 19, 451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030451

Aprilia A, Ling Z, Gill V, Chia N, Jones MA, Williams PE, Zhou W. Localized Induction Heating for Crack Healing of AISI 1020 Steel. Materials. 2026; 19(3):451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030451

Chicago/Turabian StyleAprilia, Aprilia, Zixuan Ling, Vincent Gill, Nicholas Chia, Martyn A. Jones, Paul E. Williams, and Wei Zhou. 2026. "Localized Induction Heating for Crack Healing of AISI 1020 Steel" Materials 19, no. 3: 451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030451

APA StyleAprilia, A., Ling, Z., Gill, V., Chia, N., Jones, M. A., Williams, P. E., & Zhou, W. (2026). Localized Induction Heating for Crack Healing of AISI 1020 Steel. Materials, 19(3), 451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030451