Impact of Anaerobic Pyrolysis Temperature on the Formation of Volatile Hydrocarbons in Wheat Straw

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Feedstock Preparation

2.2. Pyrolysis Procedure

2.3. Identification and Quantification

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Thermal Characterization of Chemical Compounds in Willow

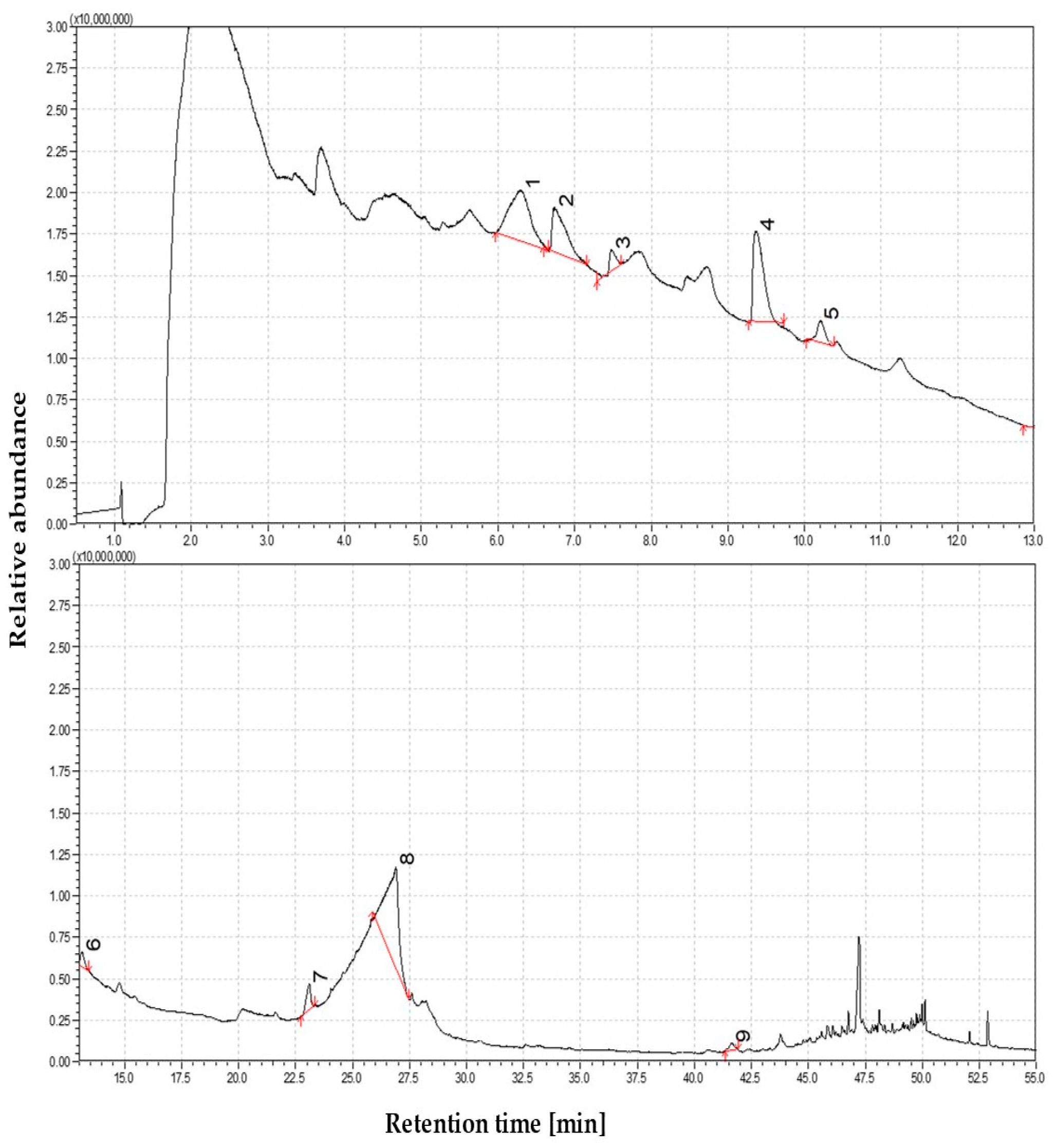

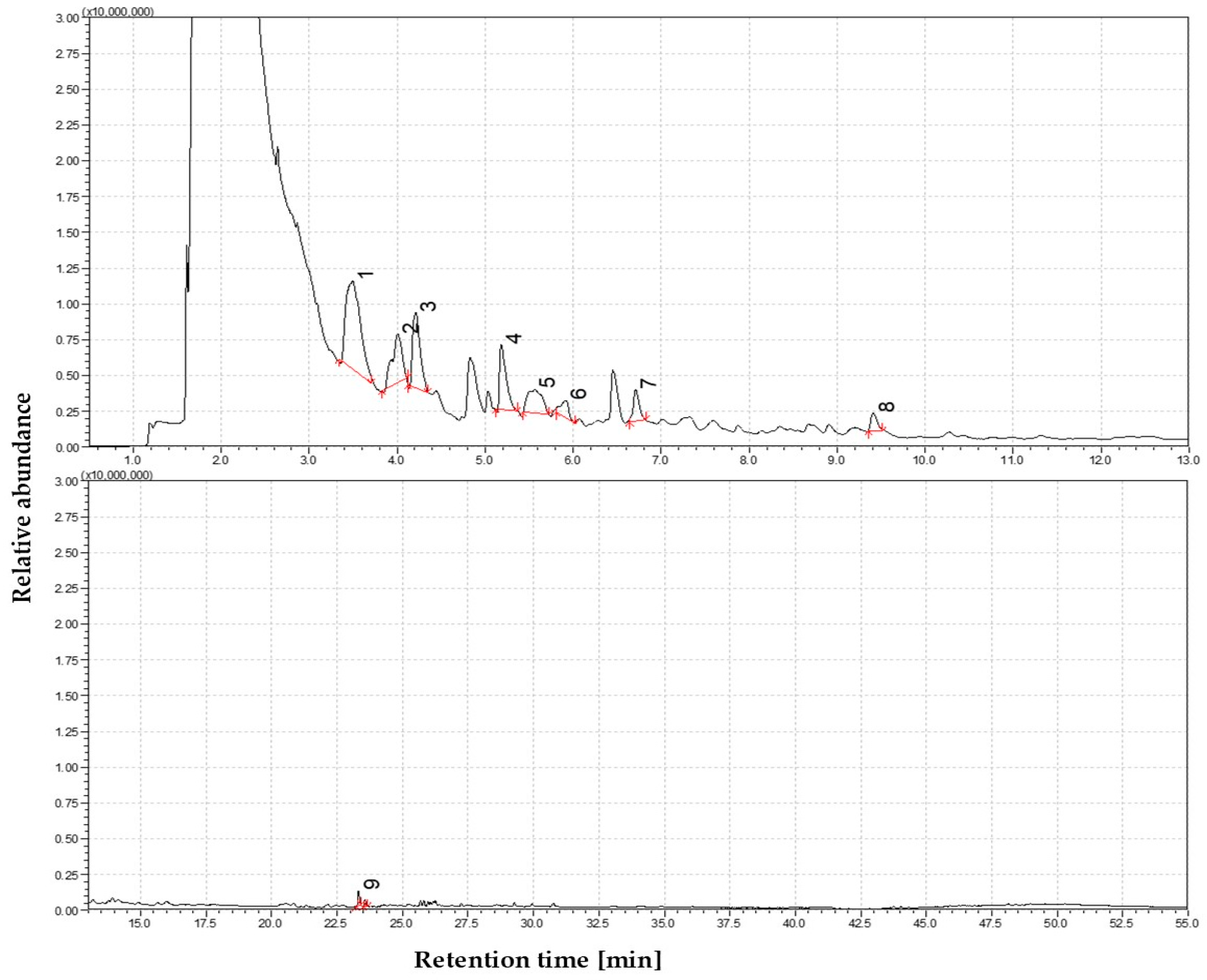

3.1.1. The Volatile Profile of Straw Pyrolysis at 350 °C

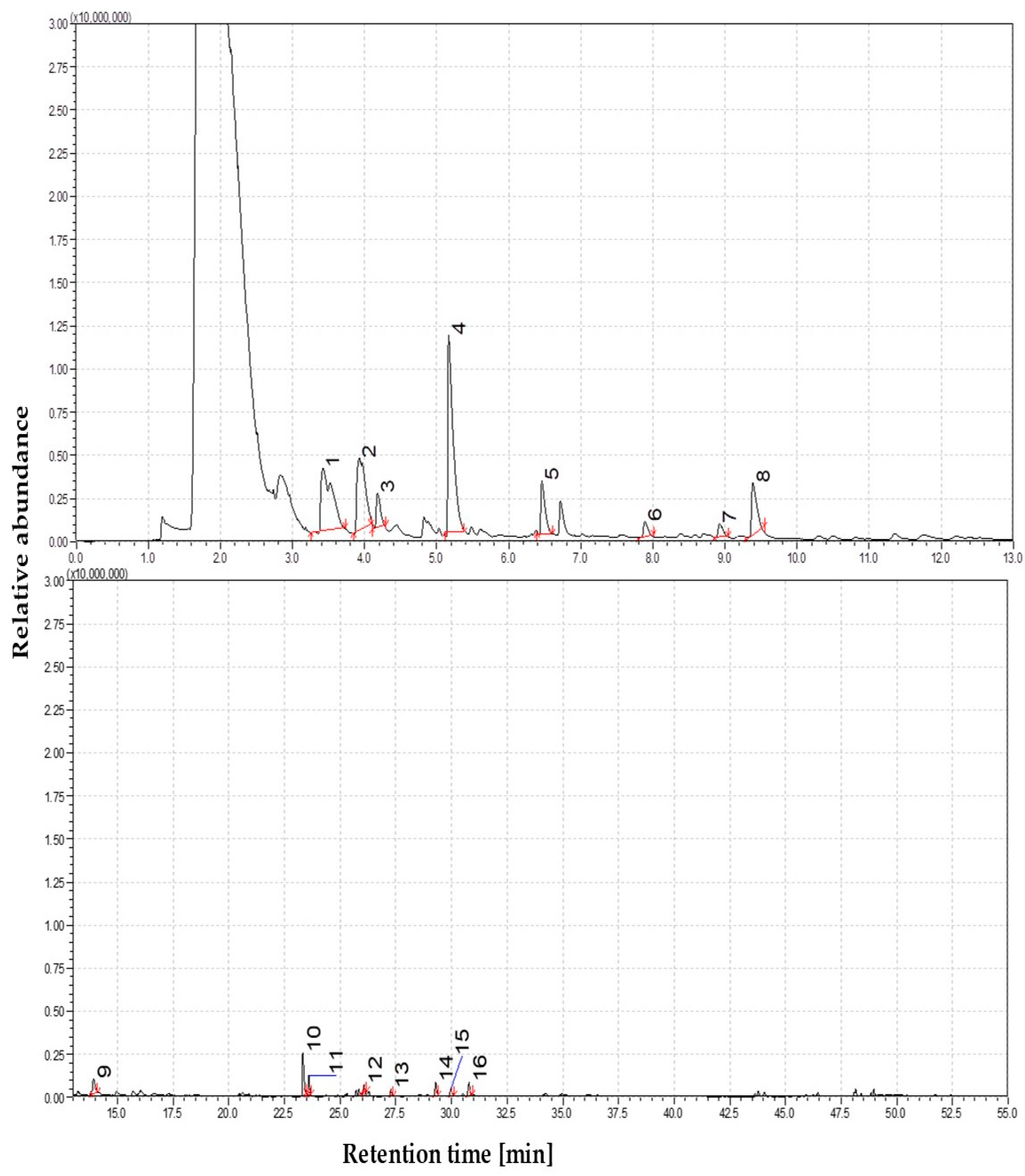

3.1.2. The Volatile Profile of Straw Pyrolysis at 450 °C

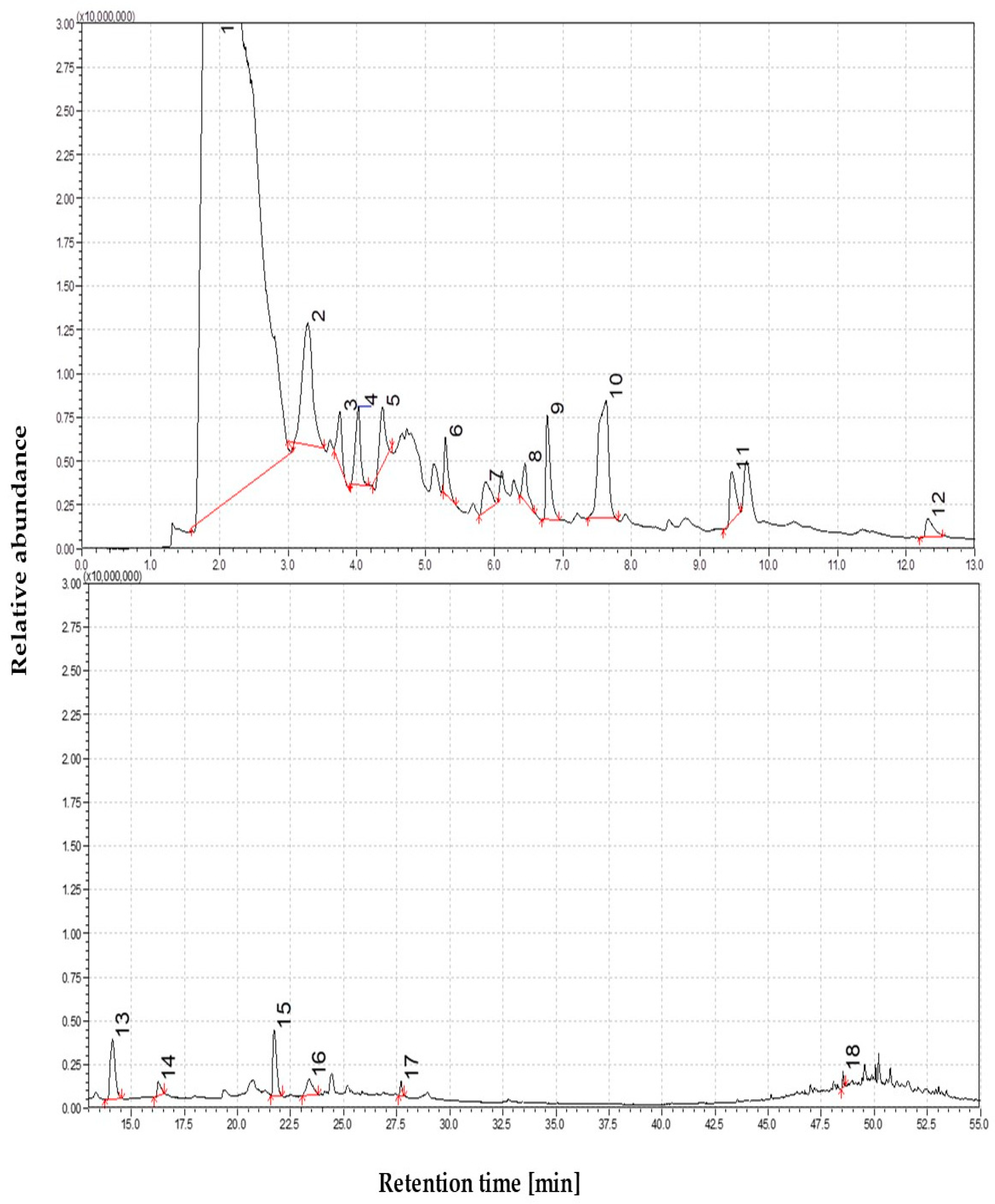

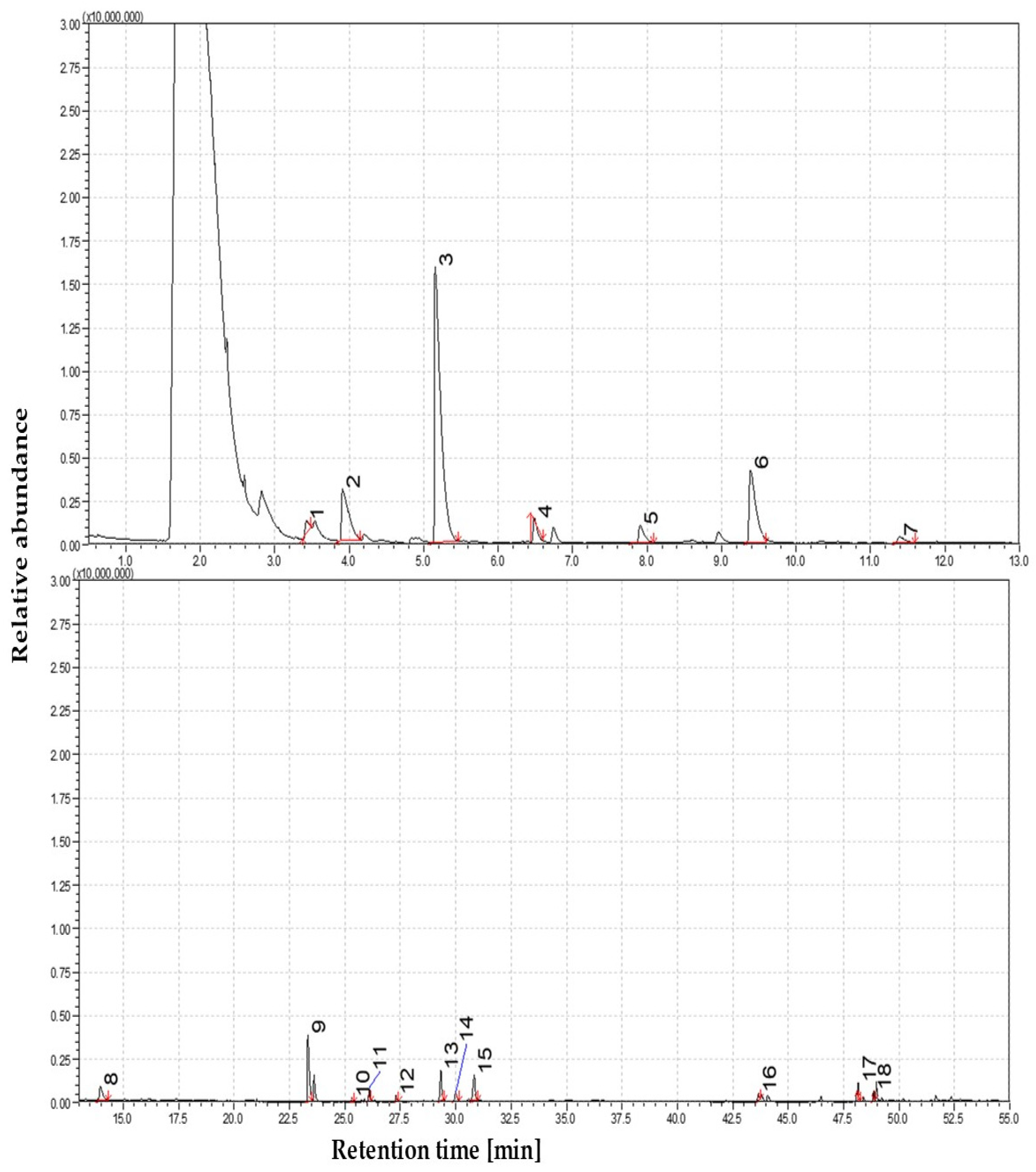

3.1.3. The Volatile Profile of Straw Pyrolysis at 550 °C

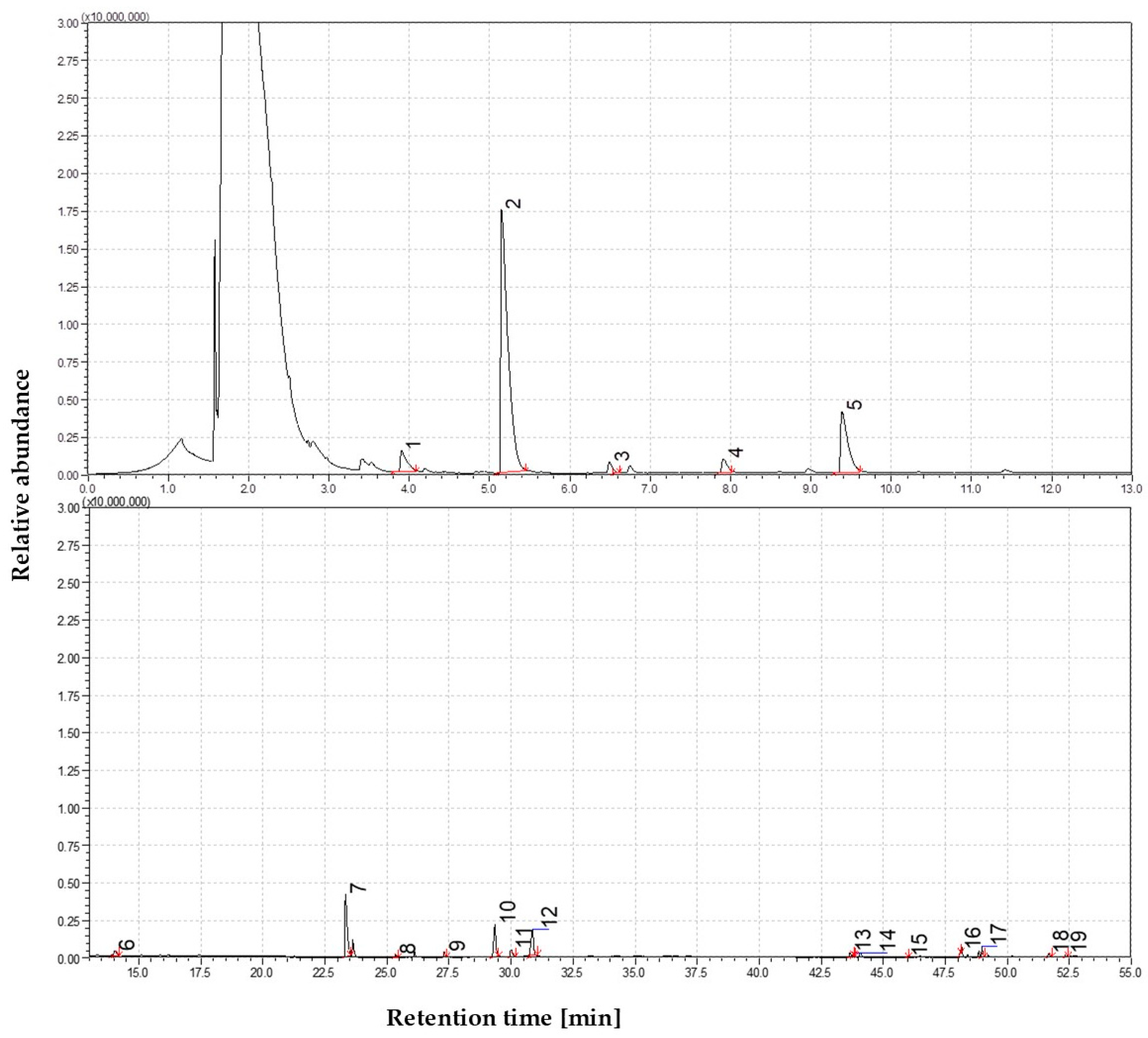

3.1.4. The Volatile Profile of Straw Pyrolysis at 650 °C

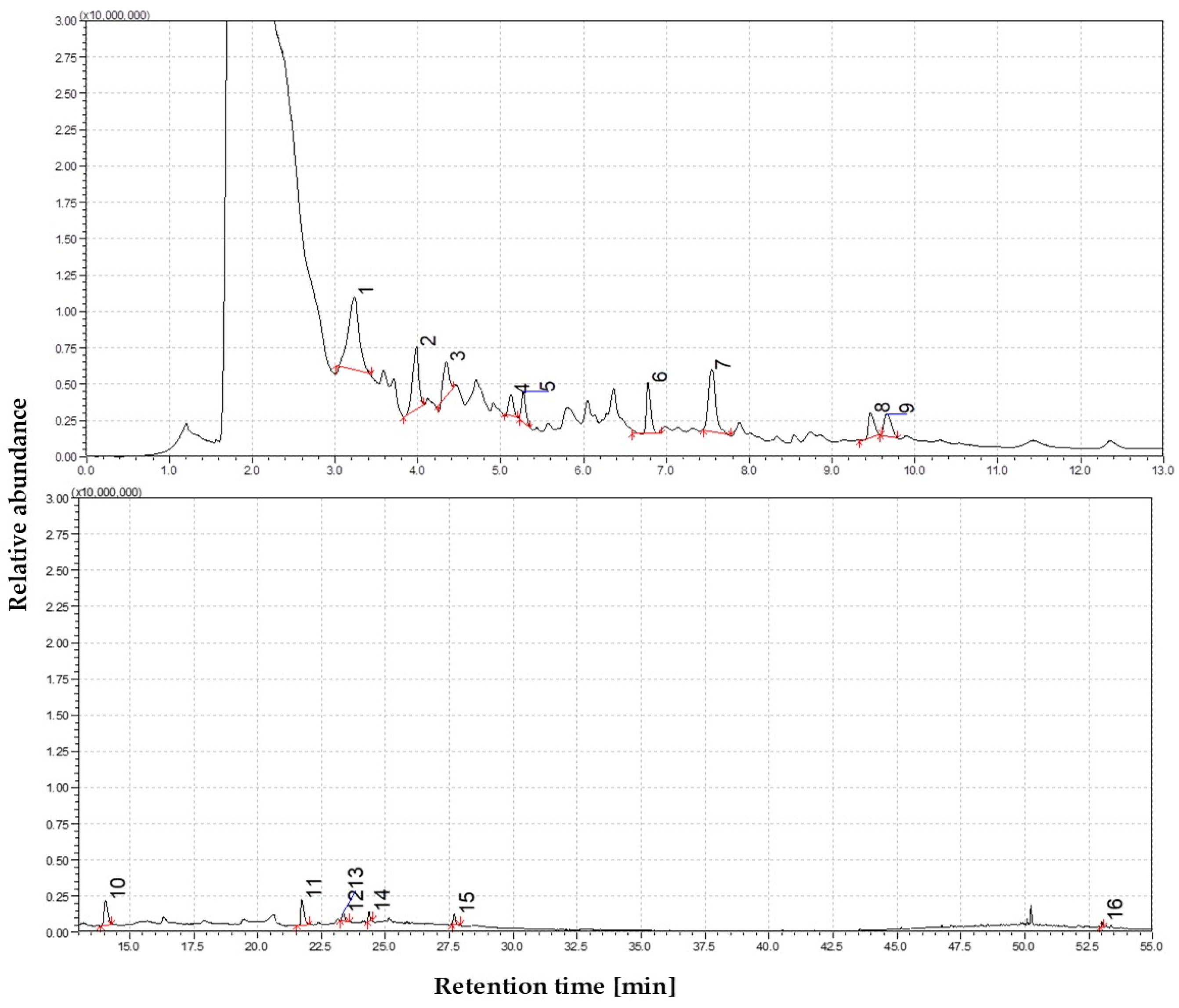

3.1.5. The Volatile Profile of Straw Pyrolysis at 750 °C

3.1.6. The Volatile Profile of Straw Pyrolysis at 850 °C

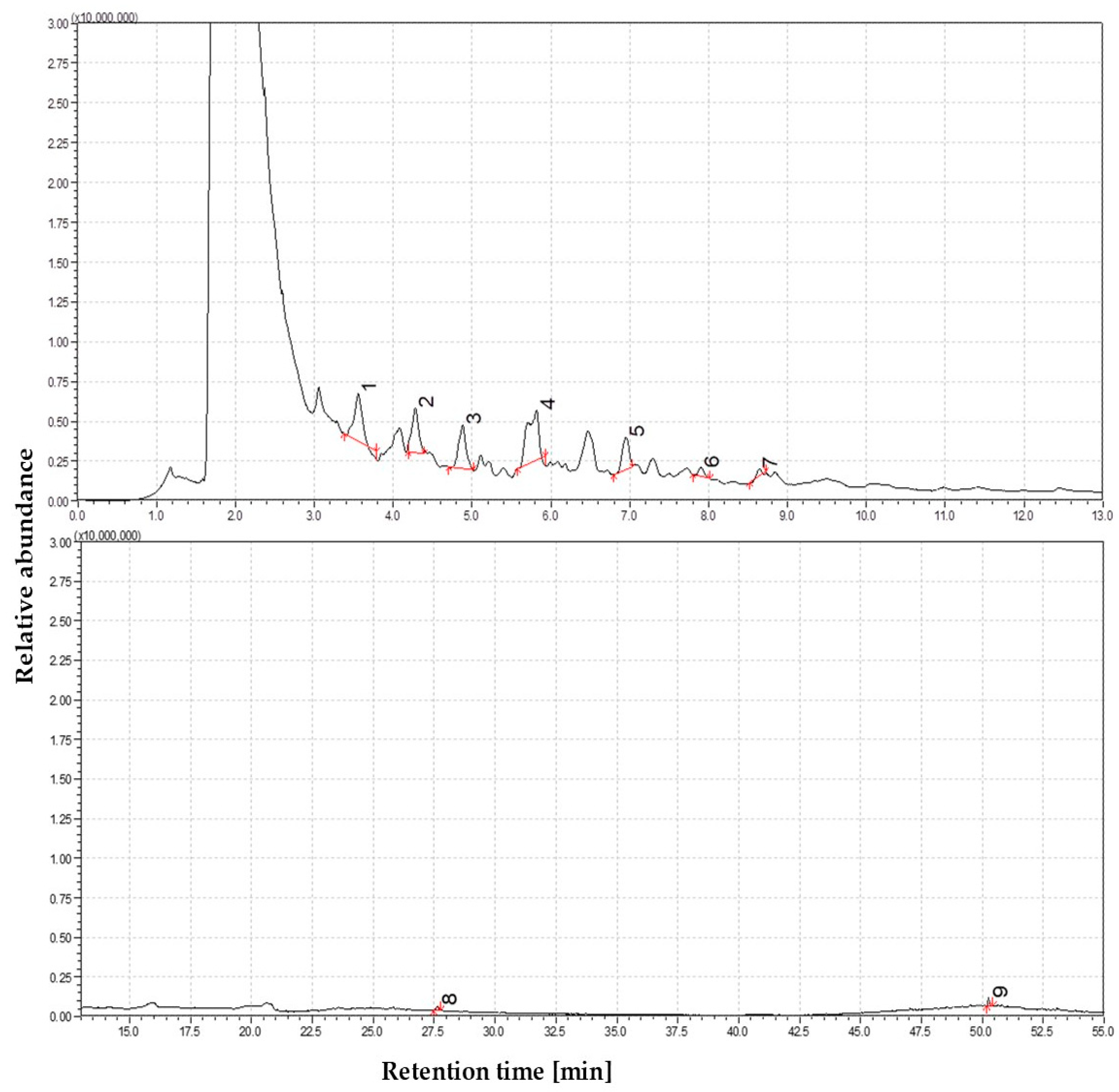

3.1.7. The Volatile Profile of Straw Pyrolysis at 950 °C

3.1.8. The Volatile Profile of Straw Pyrolysis at 1050 °C

3.2. Statistical Comparison of Volatile Compounds

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mandraveli, E.; Mitani, A.; Terzopoulou, P.; Koutsianitis, D. Oil Heat Treatment of Wood—A Comprehensive Analysis of Physical, Chemical, and Mechanical Modifications. Materials 2024, 17, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.C.; Mizanur, A.H.; Siddique, R.; Pham, H.-L. A Study on Wood Gasification for Low-Tar Gas Production. Energy 1999, 24, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Smith, C.T. A Comparative Analysis of Woody Biomass and Coal for Electricity Generation under Various CO2 Emission Reductions and Taxes. Biomass Bioenergy 2006, 30, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmaraja, J.; Shobana, S.; Arvindnarayan, S.; Vadivel, M.; Atabani, A.E.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Kumar, G. Chapter 5—Biobutanol from Lignocellulosic Biomass: Bioprocess Strategies. In Lignocellulosic Biomass to Liquid Biofuels; Yousuf, A., Pirozzi, D., Sannino, F., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 169–193. ISBN 978-0-12-815936-1. [Google Scholar]

- Aftab, M.N.; Iqbal, I.; Riaz, F.; Karadag, A.; Tabatabaei, M. Different Pretreatment Methods of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Use in Biofuel Production. In Biomass for Bioenergy; Abomohra, A.E.-F., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chaib, O.; Abatzoglou, N.; Achouri, I.E. Lignocellulosic Biomass Valorisation by Coupling Steam Explosion Treatment and Anaerobic Digestion. Energies 2024, 17, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, K.; Capareda, S.C.; Kamboj, B.R.; Malik, S.; Singh, K.; Arya, S.; Bishnoi, D.K. Biofuels Production: A Review on Sustainable Alternatives to Traditional Fuels and Energy Sources. Fuels 2024, 5, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festel, G.; Würmseher, M.; Rammer, C.; Boles, E.; Bellof, M. Modelling Production Cost Scenarios for Biofuels and Fossil Fuels in Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, A.; Funke, A.; Titirici, M.M. Hydrothermal Conversion of Biomass to Fuels and Energetic Materials. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2013, 17, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbaş, A. Biomass Resource Facilities and Biomass Conversion Processing for Fuels and Chemicals. Energy Convers. Manag. 2001, 42, 1357–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, T. Biomass for Energy. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 1755–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawan Muhammad, U. Biofuels as the Starring Substitute to Fossil Fuels. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 2, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibet, J.K.; Khachatryan, L.; Dellinger, B. Phenols from Pyrolysis and Co-Pyrolysis of Tobacco Biomass Components. Chemosphere 2015, 138, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Bai, P.; Hayakawa, K.; Zhang, L.; Tang, N. Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Emitted from Open Burning and Stove Burning of Biomass: A Brief Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; Zeng, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, J.; Cao, C.; Li, W.; Yang, J.; Qi, F. Experimental and Kinetic Modeling Investigation on Anisole Pyrolysis: Implications on Phenoxy and Cyclopentadienyl Chemistry. Combust. Flame 2019, 201, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Collado, A.; Blanco, J.M.; Gupta, M.K.; Dorado-Vicente, R. Advances in Polymers Based Multi-Material Additive-Manufacturing Techniques: State-of-Art Review on Properties and Applications. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 50, 102577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochany, J.; Maguire, R.J. Abiotic Transformations of Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Polynuclear Aromatic Nitrogen Heterocycles in Aquatic Environments. Sci. Total Environ. 1994, 144, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, K.; Gosselin, S.; Seifali Abbas-Abadi, M.; De Coensel, N.; Lizardo-Huerta, J.-C.; El Bakali, A.; Van Geem, K.M.; Gasnot, L.; Tran, L.-S. Experimental Detection of Oxygenated Aromatics in an Anisole-Blended Flame. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 6355–6369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundstedt, S.; White, P.A.; Lemieux, C.L.; Lynes, K.D.; Lambert, I.B.; Öberg, L.; Haglund, P.; Tysklind, M. Sources, Fate, and Toxic Hazards of Oxygenated Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) at PAH- PAH-Contaminated Sites. Ambio 2007, 36, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, P.; Tan, Z. Block-Wise Primal-Dual Algorithms for Large-Scale Doubly Penalized ANOVA Modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2024, 194, 107932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Agricultural Production—Crops. In Statistics Explained; Eurostat: Luxembourg City, Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Erdei, B.; Barta, Z.; Sipos, B.; Réczey, K.; Galbe, M.; Zacchi, G. Ethanol Production from Mixtures of Wheat Straw and Wheat Meal. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2010, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Sharifi, V.N.; Swithenbank, J. Environmental Sustainability of Bioethanol Production from Wheat Straw in the UK. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 28, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiasmin, M.; Waleed, A.-A.; Hua, X. Methods For Pretreatment Of Lignocellulosic Biomassand By-Products For Lignocellulolytic Enzymes Modification: A Review. Int. J. Agric. Environ. Res. 2021, 7, 102–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Mago, G.; Balan, V.; Wyman, C.E. Physical and Chemical Characterizations of Corn Stover and Poplar Solids Resulting from Leading Pretreatment Technologies. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 3948–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, F.P. Flavours: Gas chromatography. In Encyclopedia of Separation Science; Wilson, I.D., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 2814–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinhut, T.; Hadar, Y.; Chen, Y. Degradation and transformation of humic substances by saprotrophic fungi: Processes and mechanisms. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2007, 21, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wampler, T.P. Paints and coatings: Pyrolysis: Gas chromatography. In Encyclopedia of Separation Science; Wilson, I.D., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 3596–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, N.; Kothiya, S.; Rutter, A.; Walker, B.R.; Andrew, R. Gas chromatography tandem mass spectrometry offers advantages for urinary steroids analysis. Anal. Biochem. 2017, 538, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tursunov, O.; Karimov, I.; Abduganiyev, N.; Kodirov, D.; Yuhnevich, G.M.; Ali, U.F.; Mohamed, A.R.; Duong, V.; Nurfahasdi, M.; Abdivakhidov, K. Characterisation and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis of products from pyrolysis of municipal solid waste using a fixed-bed reactor. J. Ecol. Eng. 2025, 26, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaulya, S.K.; Prasad, G.M. Chapter 3—Gas Sensors for Underground Mines and Hazardous Areas. In Sensing and Monitoring Technologies for Mines and Hazardous Areas; Chaulya, S.K., Prasad, G.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 161–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheithauer, M. 17-CONCENTRATION OF SOLVENTS IN VARIOUS INDUSTRIAL ENVIRONMENTS. In Handbook of Solvents, 3rd ed.; Wypych, G., Ed.; ChemTec Publishing: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2019; pp. 1255–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage, S. 1-Chromatography. In Principles and Applications of Clinical Mass Spectrometry; Rifai, N., Horvath, A.R., Wittwer, C.T., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ingemarsson, Å.; Nilsson, M.; Pedersen, J.R.; Olsson, J.O. Slow pyrolysis of willow (Salix) studied with GC/MS and GC/FTIR/FID. Chemosphere 1999, 39, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szadkowska, D.; Szadkowski, J. The Chromatographic Analysis of Extracts from Poplar (Populus sp.)-Laying Program GC-MS. In Annals of Warsaw University of Life Sciences SGGW Forestry and Wood Technology; Warsaw University of Life Sciences: Warsaw, Poland, 2020; p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Gholizadeh, M.; Tran, C.C.; Kaliaguine, S.; Li, C.Z.; Olarte, M.; Garcia-Perez, M. Hydrotreatment of Pyrolysis Bio-Oil: A Review. Fuel Process. Technol. 2019, 195, 106140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, K.; Roman, M.; Szadkowska, D.; Szadkowski, J.; Grzegorzewska, E. Evaluation of Physical and Chemical Parameters According to Energetic Willow (Salix viminalis L.) Cultivation. Energies 2021, 14, 2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, A.V. Review of Fast Pyrolysis of Biomass and Product Upgrading. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 38, 68–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, D.; Thunman, H.; Matos, A.; Tarelho, L.; Gómez-Barea, A. Characterization and Prediction of Biomass Pyrolysis Products. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2011, 37, 611–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Kukkadapu, G.; Kiuchi, S.; Wagnon, S.W.; Kinoshita, K.; Takeda, Y.; Sakaida, S.; Konno, M.; Tanaka, K.; Oguma, M.; et al. Formation of PAHs, Phenol, Benzofuran, and Dibenzofuran in a Flow Reactor from the Oxidation of Ethylene, Toluene, and n-Decane. Combust. Flame 2022, 241, 112136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwuoha, G.N.; Oritsebinone, E.I. Chemical Fingerprinting, PAHs Characterization and Ecological Risks of Carcinogenic PAHs in Surficial Sediments of Egi Crude Oil Producing Communities, Niger-Delta, Nigeria 1 Godson Ndubuisi Iwuoha, 2 Esther Imoh Oritsebinone. Int. J. Adv. Multidiscip. Res. Stud. 2024, 4, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Kruse, S.; Schmid, R.; Cai, L.; Hansen, N.; Pitsch, H. Oxygenated PAH Formation Chemistry Investigation in Anisole Jet Stirred Reactor Oxidation by a Thermodynamic Approach. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rumaihi, A.; Shahbaz, M.; Mckay, G.; Mackey, H.; Al-Ansari, T. A Review of Pyrolysis Technologies and Feedstock: A Blending Approach for Plastic and Biomass towards Optimum Biochar Yield. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelo, N.; Antxustegi, M.; Corro, E.; Baloch, M.; Volpe, R.; Gagliano, A.; Fichera, A.; Alriols, M.G. Use of Residual Lignocellulosic Biomass for Energetic Uses and Environmental Remediation through Pyrolysis. Energy Storage Sav. 2022, 1, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, D.; Pittman, C.U., Jr.; Steele, P.H. Pyrolysis of Wood/Biomass for Bio-Oil: A Critical Review. Energy Fuels 2006, 20, 848–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, P.J. Review of the Toxicity of Biomass Pyrolysis Liquids Formed at Low Temperatures; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 1997.

- Kalvakala, K.C.; Pal, P.; Kukkadapu, G.; McNenly, M.; Aggarwal, S. Numerical Study of PAHs and Soot Emissions from Gasoline–Methanol, Gasoline–Ethanol, and Gasoline–n-Butanol Blend Surrogates. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 7052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zuo, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, H.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, L. Investigation of Component Interactions During the Hydrothermal Process Using a Mixed-Model Cellulose/Hemicellulose/Lignin/Protein and Real Cotton Stalk. Energies 2025, 18, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouches, E.; Dignac, M.F.; Zhou, S.; Carrere, H. Pyrolysis-GC–MS to Assess the Fungal Pretreatment Efficiency for Wheat Straw Anaerobic Digestion. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2017, 123, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzyka, R.; Sobek, S.; Dudziak, M.; Ouadi, M.; Sajdak, M. A Comparative Analysis of Waste Biomass Pyrolysis in Py-GC-MS and Fixed-Bed Reactors. Energies 2023, 16, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Luo, Z.; Cen, K. Mechanism Study of Wood Lignin Pyrolysis by Using TG–FTIR Analysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2008, 82, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wądrzyk, M.; Janus, R.; Lewandowski, M.; Magdziarz, A. On Mechanism of Lignin Decomposition—Investigation Using Microscale Techniques: Py-GC-MS, Py-FT-IR and TGA. Renew. Energy 2021, 177, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.Y.; Zheng, Z.Z. Analysis on Active Behavior of Wheat Straw by Py-GC-MS. In Proceedings of the Functional Materials and Nanotechnology; Trans Tech Publications Ltd.: Wollerau, Switzerland, 2012; Volume 496, pp. 189–193. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, H.S.; Park, H.J.; Park, Y.-K.; Ryu, C.; Suh, D.J.; Suh, Y.-W.; Yim, J.-H.; Kim, S.-S. Bio-Oil Production from Fast Pyrolysis of Waste Furniture Sawdust in a Fluidized Bed. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, S91–S96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Fonoll, X.; Khanal, S.K.; Raskin, L. Biological Strategies for Enhanced Hydrolysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass during Anaerobic Digestion: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 245, 1245–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brebu, M.; Vasile, C. Thermal Degradation of Lignin—A Review; Romanian Academy Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2010; Volume 44. [Google Scholar]

- Negahdar, L.; Gonzalez-Quiroga, A.; Otyuskaya, D.; Toraman, H.E.; Liu, L.; Jastrzebski, J.T.B.H.; Van Geem, K.M.; Marin, G.B.; Thybaut, J.W.; Weckhuysen, B.M. Characterization and Comparison of Fast Pyrolysis Bio-Oils from Pinewood, Rapeseed Cake, and Wheat Straw Using 13C NMR and Comprehensive GC × GC. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 4974–4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, W.-T.; Mi, H.-H.; Chang, Y.-M.; Yang, S.-Y.; Chang, J.-H. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Bio-Crudes from Induction-Heating Pyrolysis of Biomass Wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 1133–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampi, M.A.; Gurska, J.; McDonald, K.I.C.; Xie, F.; Huang, X.-D.; Dixon, D.G.; Greenberg, B.M. Photoinduced Toxicity of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons to Daphnia Magna: Ultraviolet-Mediated Effects and the Toxicity of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Photoproducts. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2006, 25, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartnik, T.; Norli, H.R.; Eggen, T.; Breedveld, G.D. Bioassay-Directed Identification of Toxic Organic Compounds in Creosote-Contaminated Groundwater. Chemosphere 2007, 66, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khudyakov, A.; Vashchenko, S.; Baiul, K.; Semenov, Y.; Krot, P. Optimization of Briquetting Technology of Fine-Grained Metallurgical Materials Based on Statistical Models of Compressibility. Powder Technol. 2022, 412, 118025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Integrated Risk Information System. EPA’s Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) Program Progress Report and Report to Congress; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer. Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs, Volumes 1–127; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Roman, K.; Szadkowska, D.; Szadkowski, J. Impact of Anaerobic Pyrolysis Temperature on the Formation of Volatile Hydrocarbons in Wheat Straw. Materials 2026, 19, 436. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020436

Roman K, Szadkowska D, Szadkowski J. Impact of Anaerobic Pyrolysis Temperature on the Formation of Volatile Hydrocarbons in Wheat Straw. Materials. 2026; 19(2):436. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020436

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoman, Kamil, Dominika Szadkowska, and Jan Szadkowski. 2026. "Impact of Anaerobic Pyrolysis Temperature on the Formation of Volatile Hydrocarbons in Wheat Straw" Materials 19, no. 2: 436. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020436

APA StyleRoman, K., Szadkowska, D., & Szadkowski, J. (2026). Impact of Anaerobic Pyrolysis Temperature on the Formation of Volatile Hydrocarbons in Wheat Straw. Materials, 19(2), 436. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020436