Influence of Processing and Mix Design Factors on the Water Demand and Strength of Concrete with Recycled Concrete Fines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods of Research

2.1. Materials

- Portland cement CEM I 42.5 (VIPCEM, Kyiv, Ukraine) of the following chemical composition (%): SiO2—22.47, Al2O3—5.26, Fe2O3—4.07, CaO—66.18, MgO—0.64, SO3—0.46, MnO—0.29;

- Silica sand with a fineness modulus of 2.1 and 1.9% of silt and dusty particles;

- Granite crushed stone with a particle size of 5–20 mm;

- Superplasticizer of polyacrylate type Dynamon SR3 (Mapei, Milan, Italy) (SP);

- Sodium silicofluoride (Na2SiF6) was applied as a chemical activator;

- Recycled concrete fines (RCF) produced in the lab with a particle size less than 1 mm (Figure 1).

2.2. Methods of Testing

2.3. Design of Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Recycled Concrete Fines

3.2. Planning of Experiments and Experimental Data

- Water demand

- Compressive strength

- Control;

- 20% recycled concrete fines;

- 20% recycled concrete fines + Na2SiF6 (chemical activation);

- 20% recycled concrete fines (ground/nonground = 50/50);

- 20% recycled concrete fines (ground + thermally treated).

4. Case Study of Concrete Proportioning

- For a given 28-day compressive strength, and for a specified amount of RCF chosen based on the required RCF content, the regression Equation (3) is used to determine the necessary dosage of superplasticizer and activation parameters (specific surface area, thermal treatment temperature, and chemical activator dosage) from the standpoint of minimum cost. This task can be solved using multicriteria optimization with local refinement, implemented in the available software (e.g., Microsoft Excel Solver (Microsoft Excel for Microsoft 365, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA), MATLAB (R2023b, MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA)).

- For the parameters obtained from Equation (3), the water demand is necessary to achieve a concrete slump class S3 determined by substituting the obtained values into Equation (1).

- Considering the selected cement, water, and RCF dosages, the consumption of aggregates is calculated from the equation of absolute volumes:

- Finally, the dosages of SP and Na2SiF6 are determined:

5. Conclusions

- By applying a set of mechanical, chemical, thermal and physico-chemical combined activation methods, the quality parameters of concrete rubble and recycled concrete fines (RCF) derived from it were determined, including the strength of the original concrete, chemical and phase composition, specific surface area, and pozzolanic activity.

- The pozzolanic activity of RCF increases with increasing specific surface area of the particles.

- Using the methodology of experimental design, six-factor experimental-statistical models were obtained for the water demand and compressive strength of concrete, taking into account cement consumption, RCF content and fineness, superplasticizer dosage, accelerator content (sodium silicofluoride), and RF thermal treatment temperature.

- Analysis of the models allowed quantitative evaluation of the influence of the studied factors, ranking them by their effect on water demand and strength, and identifying significant interaction effects. The SEM-EDS results provide evidence that the use of RCF, particularly with chemical treatment, can significantly alter the hydration chemistry and microstructure of concrete. The formation of low-Ca, Al-rich C–A–S–H phases improves durability potential, while chemical activation helps suppress carbonation and refine the matrix. Conversely, untreated or mechanically treated RCF introduces greater heterogeneity. These findings support the use of the combined activation methods as a more effective strategy for the application of RCFC in cement and concrete.

- It was established that the increase in water demand and reduction in compressive strength caused by RCF addition can be mitigated by using a polyacrylate superplasticizer and by RCF activation through thermal treatment combined with sodium silicofluoride. At a cement consumption of 300 kg/m3, RCF can be added up to 25%; at 400 kg/m3, up to 20%; and at 500 kg/m3, up to 15%, yielding comparable compressive strengths.

- The recommended ranges of fine fractions of recycled concrete (RCF) established in this study are consistent with the general provisions of existing concrete standards (e.g., EN 206 [44], ACI 318 [45]/ACI 555 [46]), which permit the use of mineral admixtures provided that the required performance criteria are met. Accordingly, RCF can be practically classified and utilized as an active mineral admixture without violating current standard specifications for structural concrete.

- Based on analysis of the models for water demand and compressive strength, and using appropriate software, a method of optimal concrete proportioning with the addition of the recycled concrete has been proposed.

- The multiparametric optimization of concrete mixtures with RCF, carried out using the developed methodology from the standpoint of minimum cost, indicates that for a target strength of 50–60 MPa, the incorporation of RCF in the amount of 50–75 kg/m3 allows a reduction in cement consumption by 18–30 kg/m3 while maintaining the overall cost of concrete.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Statistical Indicators of the Experimental–Statistical Models

Appendix A.1. Water Demand (W, Equation (1))

| Source | Sum of Squares (SS) | df | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | 400.1667 | 1.0 | 752.1205 | <0.001 |

| X2 | 6534.0 | 1.0 | 12,280.7711 | <0.001 |

| X3 | 192.6667 | 1.0 | 362.1205 | <0.001 |

| X4 | 18,704.1667 | 1.0 | 35,154.8193 | <0.001 |

| X5 | 240.0 | 1.0 | 4510.8434 | <0.001 |

| X6 | 96.0 | 1.0 | 180.4337 | <0.001 |

| I(X1 ^ 2) | 94.2937 | 1.0 | 177.2266 | <0.001 |

| I(X2 ^ 2) | 1086.5079 | 1.0 | 2042.1113 | <0.001 |

| I(X3 ^ 2) | 53.3651 | 1.0 | 100.3006 | <0.001 |

| I(X4 ^ 2) | 653.7222 | 1.0 | 1228.6827 | <0.001 |

| I(X5 ^ 2) | 343.3651 | 1.0 | 645.3609 | <0.001 |

| I(X6 ^ 2) | 30.5079 | 1.0 | 57.3402 | <0.001 |

| X1:X2 | 32.0 | 1.0 | 60.1446 | <0.001 |

| X1:X3 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.9398 | 0.3413 |

| X1:X4 | 16.0 | 1.0 | 30.0723 | <0.001 |

| X1:X5 | <0.001 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| X1:X6 | 72.0 | 1.0 | 135.3253 | <0.001 |

| X2:X3 | <0.001 | 1.0 | <0.001 | 1.0 |

| X2:X4 | 72.0 | 1.0 | 135.3253 | <0.001 |

| X2:X5 | 144.0 | 1.0 | 270.6506 | <0.001 |

| X2:X6 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 15.0361 | 0.0006 |

| X3:X4 | 4.5 | 1.0 | 8.4578 | 0.0073 |

| X3:X5 | <0.001 | 1.0 | <0.001 | 1.0 |

| X3:X6 | 144.0 | 1.0 | 270.6506 | <0.001 |

| X4:X5 | 200.0 | 1.0 | 375.9036 | <0.001 |

| X4:X6 | <0.001 | 1.0 | <0.001 | 1.0 |

| X5:X6 | <0.001 | 1.0 | <0.001 | 1.0 |

| Residual | 13.8333 | 26.0 |

Appendix A.2. Compressive Strength at 7 Days (Equation (2))

| Source | Sum of Squares (SS) | Df | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | 47.320 | 1.0 | 964.177 | 4.426 × 10−22 |

| X2 | 2167.90 | 1.0 | 44,172.077 | 1.566 × 10−43 |

| X3 | 47.039 | 1.0 | 958.464 | 4.772 × 10−22 |

| X4 | 2910.603 | 1.0 | 59,305.036 | 3.406 × 10−45 |

| X5 | 507.839 | 1.0 | 10,347.499 | 2.39 × 10−35 |

| X6 | 100.860 | 1.0 | 2055.073 | 2.816 × 10−26 |

| I(X1 ^ 2) | 47.545 | 1.0 | 968.768 | 4.167 × 10−22 |

| I(X2 ^ 2) | 35.680 | 1.0 | 727.001 | 1.561 × 10−20 |

| I(X3 ^ 2) | 13.900 | 1.0 | 283.223 | 1.694 × 10−15 |

| I(X4 ^ 2) | 0.057 | 1.0 | 1.178 | 0.287 |

| I(X5 ^ 2) | 59.245 | 1.0 | 1207.161 | 2.546 × 10−23 |

| I(X6 ^ 2) | 5.221 | 1.0 | 106.392 | 1.107 × 10−10 |

| X1:X2 | 0.061 | 1.0 | 1.248 | 0.274 |

| X1:X3 | 30.420 | 1.0 | 619.823 | 1.152 × 10−19 |

| X1:X4 | 72.675 | 1.0 | 1480.802 | 1.878 × 10−24 |

| X1:X5 | 7.605 | 1.0 | 154.955 | 1.851 × 10−12 |

| X1:X6 | 0.320 | 1.0 | 6.520 | 0.0168 |

| X2:X3 | 0.044 | 1.0 | 0.916 | 0.347 |

| X2:X4 | 6.661 | 1.0 | 135.726 | 8.052 × 10−12 |

| X2:X5 | 1.322 | 1.0 | 26.946 | 2.031 × 10−5 |

| X2:X6 | 1.037 × 10−29 | 1.0 | 2.113 × 10−28 | 1.0 |

| X3:X4 | 1.620 | 1.0 | 33.008 | 4.76 × 10−6 |

| X3:X5 | 0.0449 | 1.0 | 0.916 | 0.347 |

| X3:X6 | 6.0024 | 1.0 | 122.304 | 2.503 × 10−11 |

| X4:X5 | 15.124 | 1.0 | 308.179 | 6.158 × 10−16 |

| X4:X6 | 5.12 | 1.0 | 104.322 | 1.362 × 10−10 |

| X5:X6 | 5.404 × 10−29 | 1.0 | 1.101 × 10−27 | 1.0 |

| Residual | 1.276 | 26.0 |

Appendix A.3. Compressive Strength at 28 Days (Equation (3))

| Source | Sum of Squares (SS) | Df | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | 49.15 | 1.0 | 1080.84 | <0.001 |

| X2 | 2288.68 | 1.0 | 47,592.64 | <0.001 |

| X3 | 51.30 | 1.0 | 1039.82 | <0.001 |

| X4 | 2935.07 | 1.0 | 70,898.75 | <0.001 |

| X5 | 596.69 | 1.0 | 10,382.20 | <0.001 |

| X6 | 107.08 | 1.0 | 2414.85 | <0.001 |

| I(X1 ^ 2) | 55.08 | 1.0 | 1082.12 | <0.001 |

| I(X2 ^ 2) | 36.53 | 1.0 | 747.75 | <0.001 |

| I(X3 ^ 2) | 14.89 | 1.0 | 290.59 | <0.001 |

| I(X4 ^ 2) | 0.06 | 1.0 | 1.40 | 0.2880 |

| I(X5 ^ 2) | 68.33 | 1.0 | 1261.56 | <0.001 |

| I(X6 ^ 2) | 6.16 | 1.0 | 122.37 | <0.001 |

| X1:X2 | 0.07 | 1.0 | 1.28 | 0.3001 |

| X1:X3 | 35.48 | 1.0 | 699.87 | <0.001 |

| X1:X4 | 84.34 | 1.0 | 1762.08 | <0.001 |

| X1:X5 | 9.01 | 1.0 | 171.78 | <0.001 |

| X1:X6 | 0.35 | 1.0 | 7.46 | 0.0169 |

| X2:X3 | 0.05 | 1.0 | 0.98 | 0.3692 |

| X2:X4 | 7.26 | 1.0 | 149.41 | <0.001 |

| X2:X5 | 1.33 | 1.0 | 31.13 | <0.001 |

| X2:X6 | <0.001 | 1.0 | 0.00 | 1.0643 |

| X3:X4 | 1.90 | 1.0 | 36.76 | <0.001 |

| X3:X5 | 0.04 | 1.0 | 1.09 | 0.3978 |

| X3:X6 | 7.16 | 1.0 | 126.00 | <0.001 |

| X4:X5 | 15.78 | 1.0 | 317.99 | <0.001 |

| X4:X6 | 5.92 | 1.0 | 120.34 | <0.001 |

| X5:X6 | <0.001 | 1.0 | <0.001 | 1.0000 |

| Residual | 1.47 | 26.0 |

References

- Locher, F.W. Cement—Principles of Production and Use; Verlag Bau + Technik GmbH: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2006; p. 536. [Google Scholar]

- Carriço, A.; Bogas, J.A.; Guedes, M. Thermoactivated cementitious materials—A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 250, 118873. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Guo, Y.; Tam, V.W.; Tan, J.; Shen, A.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J. Feasibility of recycled aggregates modified with a compound method involving sodium silicate and silane as permeable concrete aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 361, 129747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waste Framework Directive. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/topics/waste-and-recycling/waste-framework-directive_en (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Runying, A.; Yangyang, G. Estimating construction and demolition waste in the building sector in China: Towards the end of the century. Waste Manag. 2024, 190, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Communities Can Assess the Debris Amount by the Unified Method. 10 July 2024. Available online: https://ustcoalition.com.ua/en/gromady-zmozhut-rahuvaty-kilkist-vidhodiv-vid-rujnuvan-za-unifikovanym-metodom (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Kaptan, K.; Cunha, S.; Aguiar, J. A review of the utilization of recycled powder from concrete waste as a cement partial replacement in cement-based materials: Fundamental properties and activation methods. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Hong, B. Evolution of recycled concrete research: A data-driven scientometric review. Low-Carbon Mater. Green Constr. 2024, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.W.Y.; Soomro, M.; Jorge Evangelista, A.C. A review of recycled aggregate in concrete applications (2000–2017). Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 172, 272–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liang, C.; Xiao, J.; Xu, J.; Ma, Z. Early-age behavior and mechanical properties of cement-based materials with various types and fineness of recycled powder. Struct. Concr. 2022, 23, 1253–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorkin, L.I.; Solomatov, V.I.; Vyrovoy, V.N.; Chudnovsky, S.M. Cement Concretes with Mineral Fillers; Budivelnyk: Kyiv, Ukraine, 1991; p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, Y.; Aytekin, B.; Kaya, T.; Mardani, A. Investigation of pozzolanic activity of recycled concrete powder: Effect of cement fineness, grain size distribution and water/cement ratio. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 79, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsakulthai, V. Effect of recycled concrete powder on strength, electrical resistivity, and water absorption of self-compacting mortars. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 15, e00725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Q.; Cheng, L.X.; Ying, Y.; Yang, F.H. Utilization of all components of waste concrete: Recycled aggregate strengthening, recycled fine powder activity, composite recycled concrete and life cycle assessment. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 82, 108255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yu, Q.; Zhan, B.; Gao, P.; Guo, B.; Chu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Bian, P. Activity quantification and assessment of recycled concrete powder based on the contributions of the dilution effect, physical effect and chemical effect. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 442, 140918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donatello, S.; Tyrer, M.; Cheeseman, C.R. Comparison of test methods to assess pozzolanic activity. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2010, 32, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volmer, M. Kinetics of Phase Formation (Kinetik Der Phasenbildung); Central Air Documents: Berlin, Germany, 1966; p. 219. [Google Scholar]

- Svatovskaya, L.B.; Sychev, M.M. Activated Cement Hardening; Stroiizdat: Leningrad, USSR, 1983; p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenholm, J.B.; Peiponen, K.-E.; Gornov, E. Materials cohesion and interaction forces. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2008, 141, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, X. Synergistic effects of nano-silica and fly ash on the mechanical properties and durability of internal-cured concrete incorporating artificial shale ceramsite. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 66, 105905. [Google Scholar]

- Dvorkin, L.; Zhitkovsky, V.; Tracz, T.; Sitarz, M.; Mróz, K. Mechanical–Chemical Activation of Cement-Ash Binders to Improve the Properties of Heat-Resistant Mortars. Materials 2024, 17, 5760. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wu, Z.; Li, C.; Pan, Y.; Wang, J.; Qiu, J.; Ren, S.; Xu, H. Synergistic effect of sodium metasilicate and sodium fluorosilicate in an accelerator on cement hydration. Adv. Cem. Res. 2025, 37, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, Z.; Rodriguez, C.; Barbera, E.; Leal da Silva, W.R.; Bezzo, F. Wet carbonation of industrial recycled concrete fines: Experimental study and reaction kinetic modeling. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 21412–21425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likes, L.; Markandeya, A.; Haider, M.M.; Bollinger, D.; McCloy, J.S.; Nassiri, S. Recycled concrete and brick powders as supplements to Portland cement for more sustainable concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 364, 132651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Wang, L.; Xu, S.; Ma, Y.; Ye, G. Surface characterization of carbonated recycled concrete fines and its effect on the rheology, hydration and strength development of cement paste. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 114, 103809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, S.A.; Bekzhanova, Z.; Murzakarimova, A. A review of improvement of interfacial transition zone and adherent mortar in recycled concrete aggregate. Buildings 2022, 12, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaud, S.; van Zijl, G.P.A.G. Combined action of mechanical pre-cracks and ASR strain in concrete. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2017, 15, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Deng, X.; Lu, Z.; Li, X.; Hou, L.; Jiang, J.; Yang, F.; Zhang, J.; He, K. Recycled concrete fines as a supplementary cementitious material: Mechanical performances, hydration, and microstructures. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teune, I.E.; Schollbach, K.; Florea, M.V.A.; Brouwers, H.J.H. Carbonation of hydrated cement: The impact of carbonation conditions on CO2 sequestration and reactivity. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 79, 107785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brabandere, L.; Grigorjev, V.; Van den Heede, P.; Nachtergaele, H.; Degezelle, K.; De Belie, N. Using fines from recycled high-quality concrete as a substitute for cement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Ma, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, S.; Hai, R.; Zhu, Z. Early-age behaviour of Portland cement incorporating ultrafine recycled powder. Materials 2024, 17, 5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Kim, G.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Park, S. Assessment of the applicability of waste concrete fine powder as raw material for cement clinker. Recycling 2025, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DSTU B V.2.7-71-98; Crushed Stone and Gravel from Dense Rocks and Industrial Waste for Construction Works. State Committee of Ukraine for Standardization, Metrology and Certification: Kyiv, Ukraine, 1998. (In Ukrainian)

- ISO 863:2008; Cement—Test Methods—Determination of Consistency and Setting Time. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- EN 196-5:2011; Methods of Testing Cement—Part 5: Pozzolanicity Test for Pozzolanic Cement. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- EN 196-6:2019; Methods of Testing Cement—Part 6: Determination of Fineness. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- ASTM E70-19; Standard Test Method for pH of Aqueous Solutions with the Glass Electrode. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- EN 12390-3: 2019; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 3: Compressive Strength of Test Specimens. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Box, G.E.P.; Hunter, J.S.; Hunter, W.G. Statistics for Experimenters: Design, Discovery, and Innovation, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; p. 655. [Google Scholar]

- Dvorkin, L.; Dvorkin, O.; Ribakov, Y. Mathematical Experiments Planning in Concrete Technology; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2012; p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- TIBCO Statistica 14.0 Installation Guide. Available online: https://docs.tibco.com/pub/stat/14.0.0/doc/pdf/TIB_stat_14.0_installation.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Chen, L.; Wei, M.; Lei, N.; Li, H. Effect of chemical–thermal activation on the properties of recycled fine powder cementitious materials. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höffgen, J.P.; Bruckschlögl, S.; Wetz, B.; Dehn, F. Influence of thermally activated industrial concrete fines of different origin on mortar strength development. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 206:2013+A2:2021; Concrete—Specification, Performance, Production and Conformity. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- ACI 318-23; Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary. American Concrete Institute (ACI): Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2023.

- ACI 555R-01; Removal and Reuse of Hardened Concrete. American Concrete Institute (ACI): Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2016.

| Category | Feature | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle morphology of RCFs | Irregular, angular particle shape | RCF after mechanical treatment (crushing and milling) exhibits a rough surface | [23] |

| High surface area of particles | Increasing the specific surface area, more reactive sites that can promote pozzolanic and nucleation activity | [24] | |

| Heterogeneous composition | Particles may contain unhydrated cement grains, calcium hydroxide (portlandite), and C–S–H, calcium carbonate | [25] | |

| Matrix Densification | Changes in ITZ density | More compact microstructure and a denser ITZ in the concrete with RCF compared to a conventional one | [26,27] |

| Pore refinement | Ultrafines may fill microvoids and capillary pores, reducing the overall porosity of the cement matrix | [27] | |

| Reaction products | Secondary hydration products | Secondary calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H), portlandite (CH), ettringite (AFt), and AFm phases. | [28] |

| c | Mainly CaCO3 formed from aged concrete | [29] | |

| Unhydrated cement clinker phases | C3S, C2S, C3A, C4AF—small but potentially reactive fraction | [7] | |

| Inert materials | SiO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3 | [30] | |

| ITZ Improvement | Enhanced bonding | ITZ in RCF containing concrete generally shows fewer voids and microcracks compared to control | [26,27] |

| Nucleation effect | Ultrafines act as nucleation sites for hydration products, improving the continuity between aggregate and paste phases | [31] | |

| Weakness of the waste | Localized defects | Microcracks or weakly bonded zones, particularly at high replacement ratios, where excess fines can disrupt hydration balance | [30] |

| Inert phases | Ultrafine fractions may include inert or carbonated particles (e.g., CaCO3), which do not contribute to reactivity and can limit performance gains | [30,32] |

| Factors | Variation Levels | Variation Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Coded | −1 | 0 | +1 | |

| Specific surface area of recycled concrete fines (Ssp, m2/kg) | X1 | 130 | 250 | 370 | 120 |

| Cement consumption (C, kg/m3) | X2 | 300 | 400 | 500 | 100 |

| Temperature of thermal treatment of recycled concrete fines, (T, °C), | X3 | 0 | 300 | 600 | 300 |

| Dosage of superplasticizer (% of cement mass), SP | X4 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Recycled concrete fines dosage (RCF, kg/m3) | X5 | 10 | 55 | 100 | 45 |

| Dosage of Na2SiF6 (as % of RCF mass), Na2SiF6 | X6 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Chemical Composition, % | CaO | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MgO | |

| 13.2 | 75.5 | 6.28 | 3.56 | 0.61 | ||

| Mineralogical Composition, % | Quartz | Feldspars | Calcite | C3S | C2S | Hydrated Cement Products |

| 43.3 | 15.5 | 10.9 | 0.86 | 2.09 | 28.3 | |

| Thermal Treatment | Specific Surface Area of Recycled Concrete Fines, m2/kg | pH | Pozzolanic Activity of Recycled Concrete Fines, mg/g |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 130 | 8.1 | 40.5 |

| 250 | 9.2 | 52.3 | |

| 370 | 10.3 | 70.4 | |

| Heat-treated 600 °C | 130 | 8.3 | 42.2 |

| 250 | 9.5 | 60.1 | |

| 370 | 11.7 | 78.8 |

| No. | Value of the Factors at Experimental Points | Output Parameters | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Demand (W, L/m3) | W/C | Compressive Strength (MPa) | ||||||||

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | X5 | X6 | |||||

| 7 Days (fcm7) | 28 Days (fcm28) | |||||||||

| 1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 199 | 0.66 | 21.0 | 25.2 |

| 2 | +1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 205 | 0.68 | 13.7 | 20.5 |

| 3 | −1 | +1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 234 | 0.47 | 38.0 | 47.6 |

| 4 | +1 | +1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 248 | 0.50 | 31.1 | 43.3 |

| 5 | −1 | −1 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 0 | 151 | 0.50 | 36.9 | 46.2 |

| 6 | +1 | −1 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 0 | 153 | 0.51 | 38.2 | 52.7 |

| 7 | −1 | +1 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 0 | 174 | 0.35 | 57.6 | 73.4 |

| 8 | +1 | +1 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 0 | 184 | 0.37 | 59.2 | 70.3 |

| 9 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 180 | 0.60 | 29.6 | 36.8 |

| 10 | 0 | +1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 207 | 0.41 | 47.9 | 60.8 |

| 11 | 0 | −1 | +1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 186 | 0.62 | 32.1 | 42.8 |

| 12 | 0 | +1 | +1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 213 | 0.43 | 50.7 | 67.2 |

| 13 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 194 | 0.65 | 19.7 | 25.4 |

| 14 | 0 | +1 | −1 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 233 | 0.47 | 39.1 | 51.0 |

| 15 | 0 | −1 | +1 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 200 | 0.67 | 22.5 | 31.8 |

| 16 | 0 | +1 | +1 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 239 | 0.48 | 42.2 | 57.8 |

| 17 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 210 | 0.53 | 27.9 | 34.9 |

| 18 | 0 | 0 | +1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 211 | 0.53 | 28.6 | 38.9 |

| 19 | 0 | 0 | −1 | +1 | 0 | −1 | 156 | 0.39 | 47.5 | 61.1 |

| 20 | 0 | 0 | +1 | +1 | 0 | −1 | 154 | 0.39 | 49.9 | 67.5 |

| 21 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 0 | +1 | 200 | 0.50 | 29.2 | 37.5 |

| 22 | 0 | 0 | +1 | −1 | 0 | +1 | 213 | 0.53 | 32.3 | 43.9 |

| 23 | 0 | 0 | −1 | +1 | 0 | +1 | 146 | 0.37 | 51.9 | 66.9 |

| 24 | 0 | 0 | +1 | +1 | 0 | +1 | 156 | 0.39 | 56.9 | 65.0 |

| 25 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 197 | 0.49 | 35.9 | 44.0 |

| 26 | +1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 207 | 0.52 | 26.9 | 36.9 |

| 27 | −1 | 0 | 0 | +1 | −1 | 0 | 153 | 0.38 | 50.9 | 63.8 |

| 28 | +1 | 0 | 0 | +1 | −1 | 0 | 159 | 0.40 | 50.4 | 67.9 |

| 29 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | +1 | 0 | 227 | 0.57 | 22.0 | 27.4 |

| 30 | +1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | +1 | 0 | 237 | 0.59 | 16.9 | 25.5 |

| 31 | −1 | 0 | 0 | +1 | +1 | 0 | 163 | 0.41 | 42.5 | 54.4 |

| 32 | +1 | 0 | 0 | +1 | +1 | 0 | 169 | 0.42 | 45.9 | 63.7 |

| 33 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 180 | 0.60 | 30.7 | 39.6 |

| 34 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 209 | 0.42 | 49.1 | 63.8 |

| 35 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | +1 | −1 | 194 | 0.65 | 20.9 | 28.4 |

| 36 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 0 | +1 | −1 | 235 | 0.47 | 40.5 | 54.2 |

| 37 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | +1 | 178 | 0.59 | 34.8 | 45.0 |

| 38 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | +1 | 203 | 0.41 | 53.2 | 69.2 |

| 39 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | +1 | +1 | 192 | 0.64 | 25.0 | 33.8 |

| 40 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 0 | +1 | +1 | 229 | 0.46 | 44.6 | 59.6 |

| 41 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 193 | 0.48 | 38.6 | 46.8 |

| 42 | +1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 195 | 0.49 | 32.3 | 43.4 |

| 43 | −1 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 192 | 0.48 | 36.3 | 46.8 |

| 44 | +1 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 195 | 0.49 | 37.8 | 53.7 |

| 45 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | +1 | 177 | 0.44 | 41.9 | 51.6 |

| 46 | +1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | +1 | 191 | 0.48 | 34.8 | 47.0 |

| 47 | −1 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 0 | +1 | 188 | 0.47 | 42.0 | 54.1 |

| 48 | +1 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 0 | +1 | 203 | 0.51 | 42.7 | 59.8 |

| 49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 186 | 0.47 | 40.6 | 53.4 |

| 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 188 | 0.47 | 41.3 | 52.4 |

| 51 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 187 | 0.47 | 40.9 | 53.7 |

| 52 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 190 | 0.48 | 41.0 | 52.9 |

| 53 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 190 | 0.48 | 41.5 | 53.6 |

| 54 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 188 | 0.47 | 40.1 | 52.4 |

| Output Parameter | Factors That Increase the Parameter | Factors That Decrease the Parameter |

|---|---|---|

| Water demand, L/m3 | X2 > X5 > X1 > X3 | X4 > X6 |

| Compressive strength (7, 28 days) | X4 > X2 > X6 > X3 | X5 > X1 |

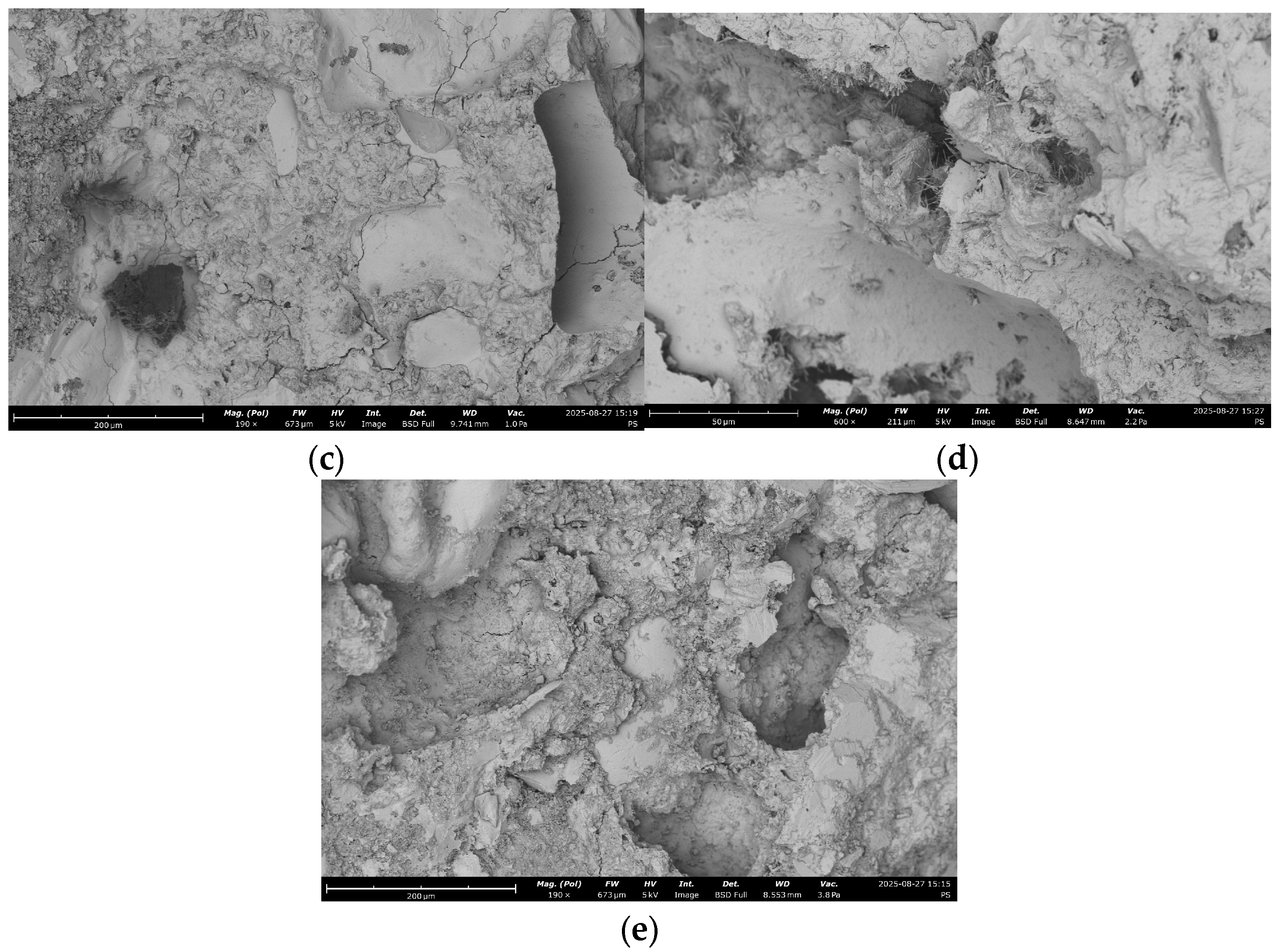

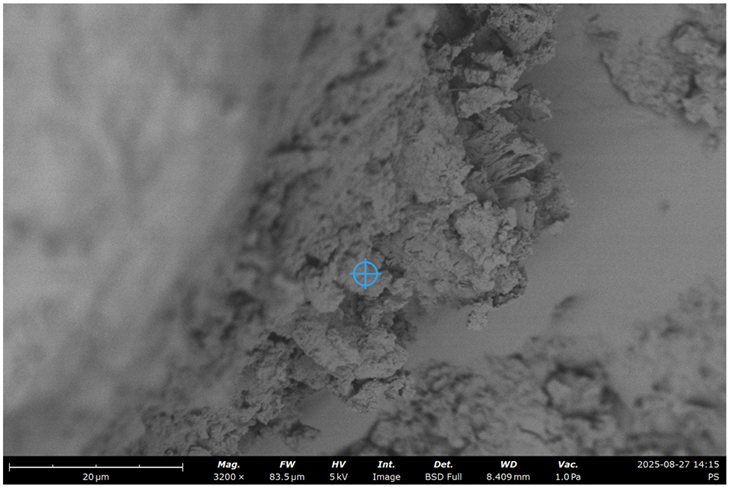

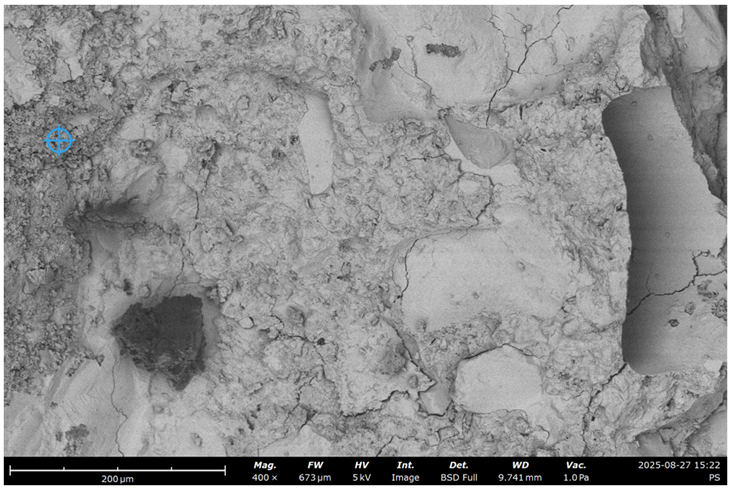

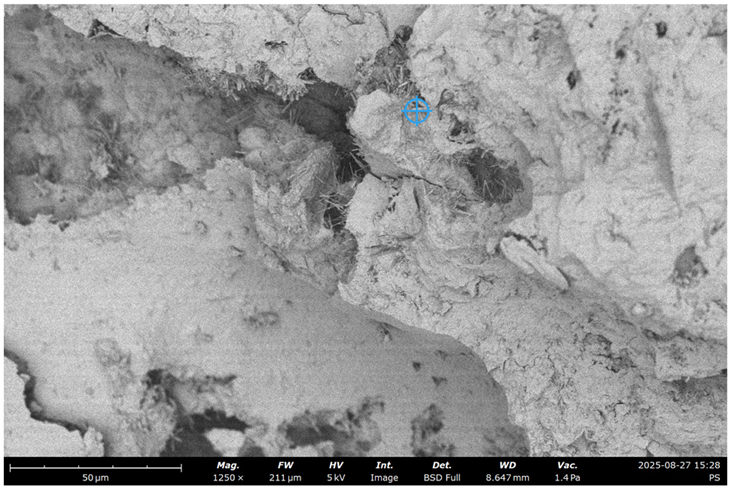

| # | RCF | Treatment | SEM Image with EDS Indicative Point | Ca/Si | Al/Si | C, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | - |  | 2.8 | 3.4 | 5.2 |

| 2 | 20% | - |  | 1.1 | 0.4 | 16 |

| 3 | 20% | Chemical |  | 1.1 | 0.2 | 4.8 |

| 4 | 20% | Mechanical |  | 1.5 | 0.4 | 12.5 |

| 5 | 20% | Mechanical + thermal |  | 1.1 | 0.16 | 2.4 |

| fc28 (MPa) | RCF (kg/m3) | C (kg/m3) | SP (% of C) | W (L/m3) | W/C | Ssp (m2/kg) | T (°C) | Na2SiF6 (% of RCF) | Cost (EUR/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 100 | 304.5 | 0.99 | 160 | 0.53 | 336 | 330 | 0.91 | 47.26 |

| 75 | 301.9 | 0.95 | 156 | 0.52 | 331 | 230 | 0.77 | 44.86 | |

| 50 | 301.2 | 0.93 | 148 | 0.49 | 207 | 54 | 0.99 | 42.93 | |

| 25 | 300.0 | 0.82 | 163 | 0.54 | 292 | 245 | 0.84 | 41.82 | |

| 0 | 318.5 | 1.00 | 162 | 0.51 | 130 | 0 | 0.00 | 44.58 | |

| 60 | 100 | 377.2 | 0.99 | 162 | 0.43 | 321 | 284 | 0.92 | 57.05 |

| 75 | 351.0 | 0.97 | 159 | 0.45 | 343 | 427 | 0.87 | 52.92 | |

| 50 | 328.1 | 0.95 | 157 | 0.48 | 313 | 524 | 0.99 | 48.55 | |

| 25 | 316.9 | 0.97 | 160 | 0.50 | 334 | 576 | 0.99 | 45.79 | |

| 0 | 384.4 | 1.00 | 161 | 0.42 | 130 | 0 | 0.00 | 53.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dvorkin, L.; Zhitkovsky, V.; Lushnikova, N.; Rudoi, V. Influence of Processing and Mix Design Factors on the Water Demand and Strength of Concrete with Recycled Concrete Fines. Materials 2026, 19, 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020237

Dvorkin L, Zhitkovsky V, Lushnikova N, Rudoi V. Influence of Processing and Mix Design Factors on the Water Demand and Strength of Concrete with Recycled Concrete Fines. Materials. 2026; 19(2):237. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020237

Chicago/Turabian StyleDvorkin, Leonid, Vadim Zhitkovsky, Nataliya Lushnikova, and Vladyslav Rudoi. 2026. "Influence of Processing and Mix Design Factors on the Water Demand and Strength of Concrete with Recycled Concrete Fines" Materials 19, no. 2: 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020237

APA StyleDvorkin, L., Zhitkovsky, V., Lushnikova, N., & Rudoi, V. (2026). Influence of Processing and Mix Design Factors on the Water Demand and Strength of Concrete with Recycled Concrete Fines. Materials, 19(2), 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020237