3D Printing of Cement-Based Materials Using Seawater for Simulated Marine Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. General Assessment of the Use of Seawater for 3D Printing Applications

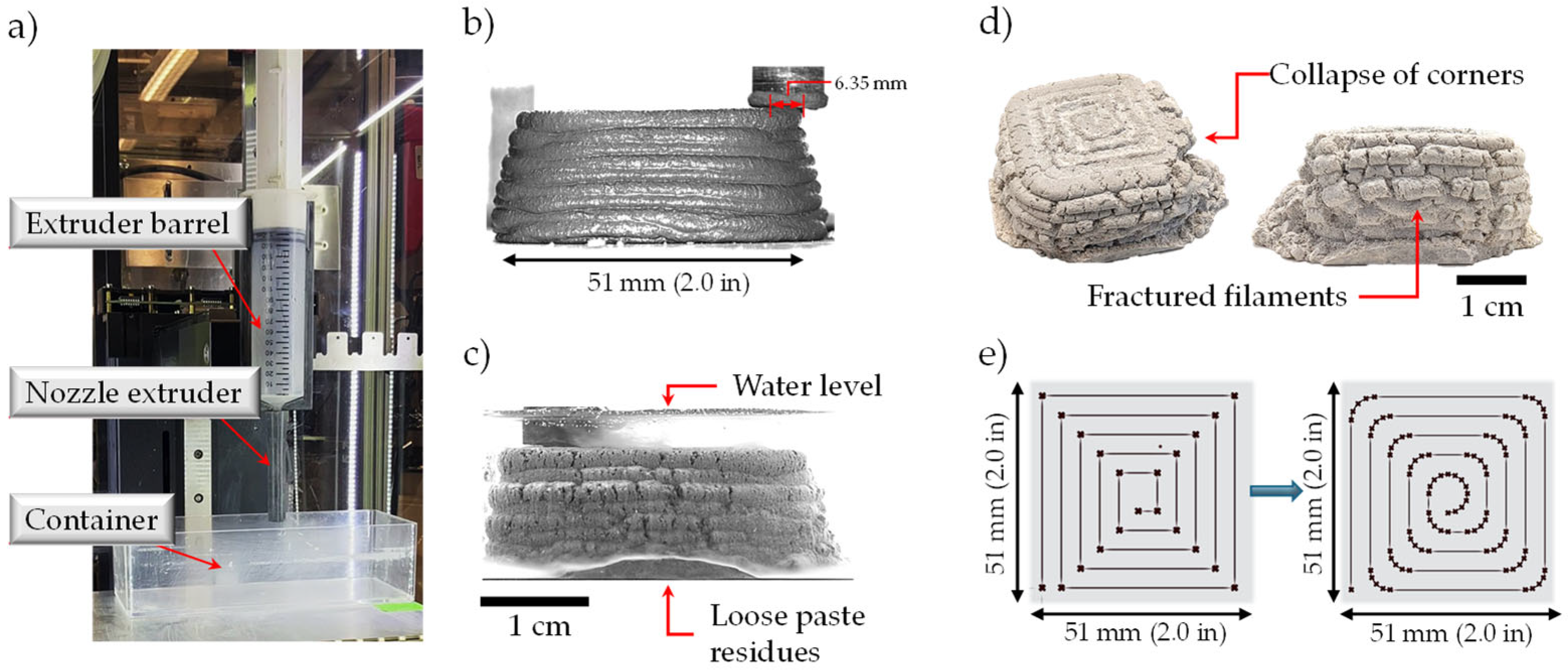

2.2.2. 3D Printing System

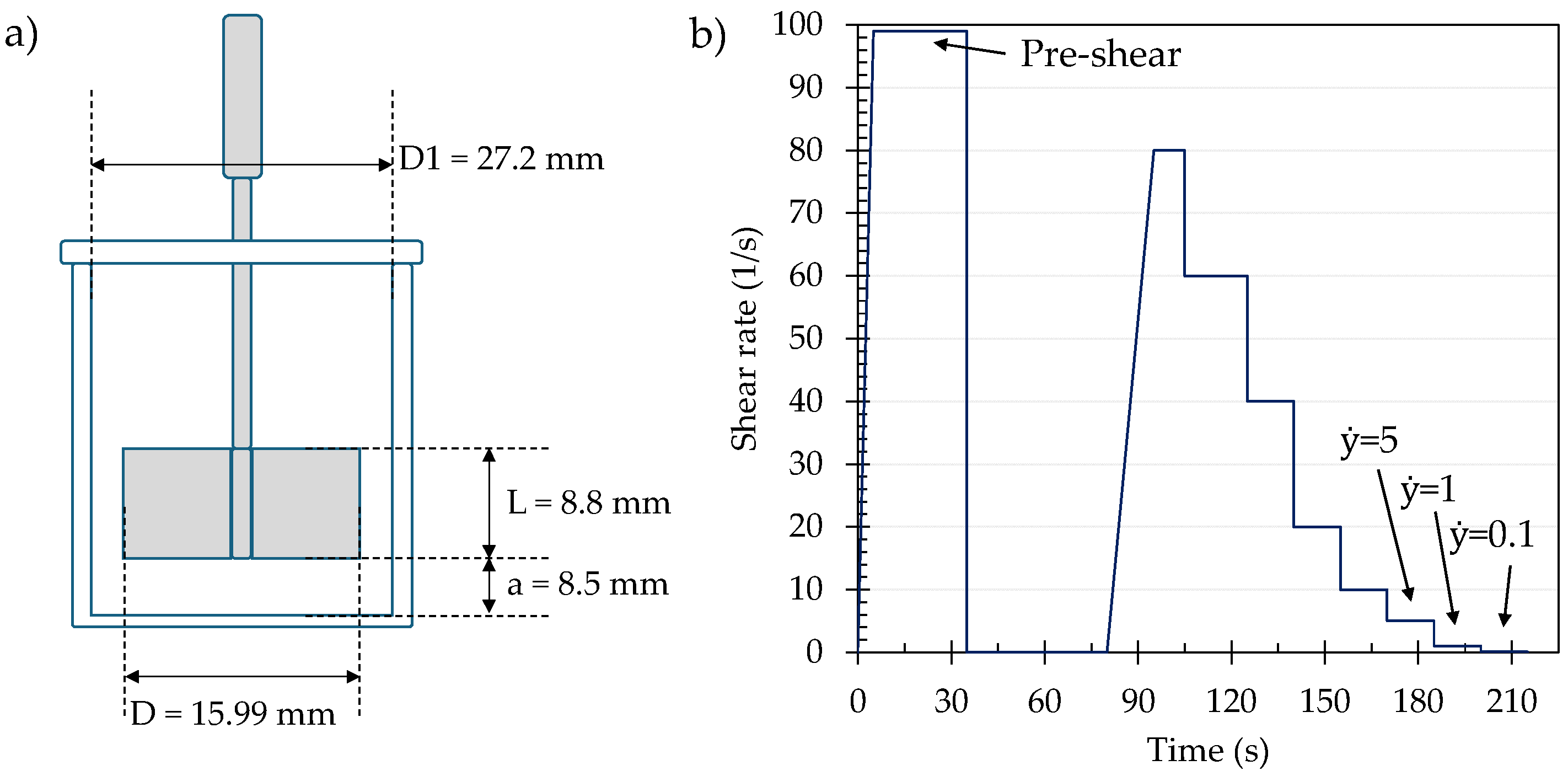

2.2.3. Rheological Characterization

2.2.4. Isothermal Calorimetry

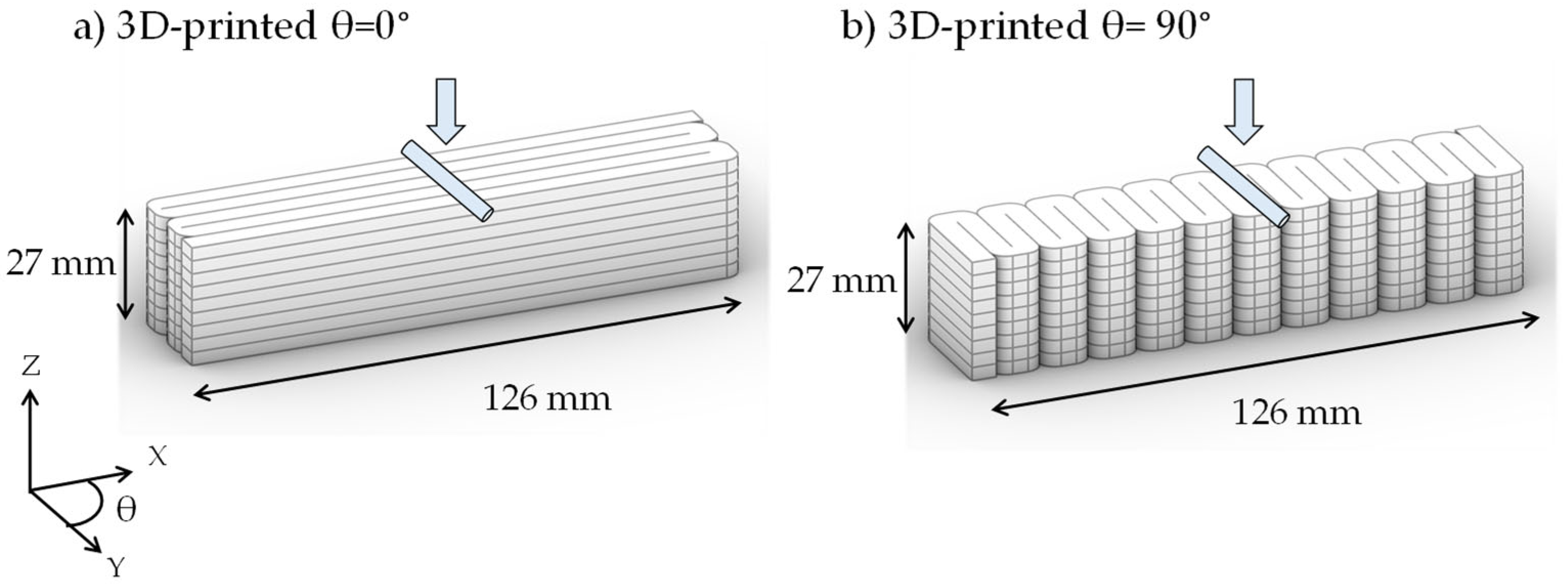

2.2.5. Compressive and Flexural Strength

2.2.6. Dimensional Accuracy of 3D-Printed Elements

2.2.7. Hardened-State Density

2.2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of the Effect of Seawater on Rheology and Heat of Hydration

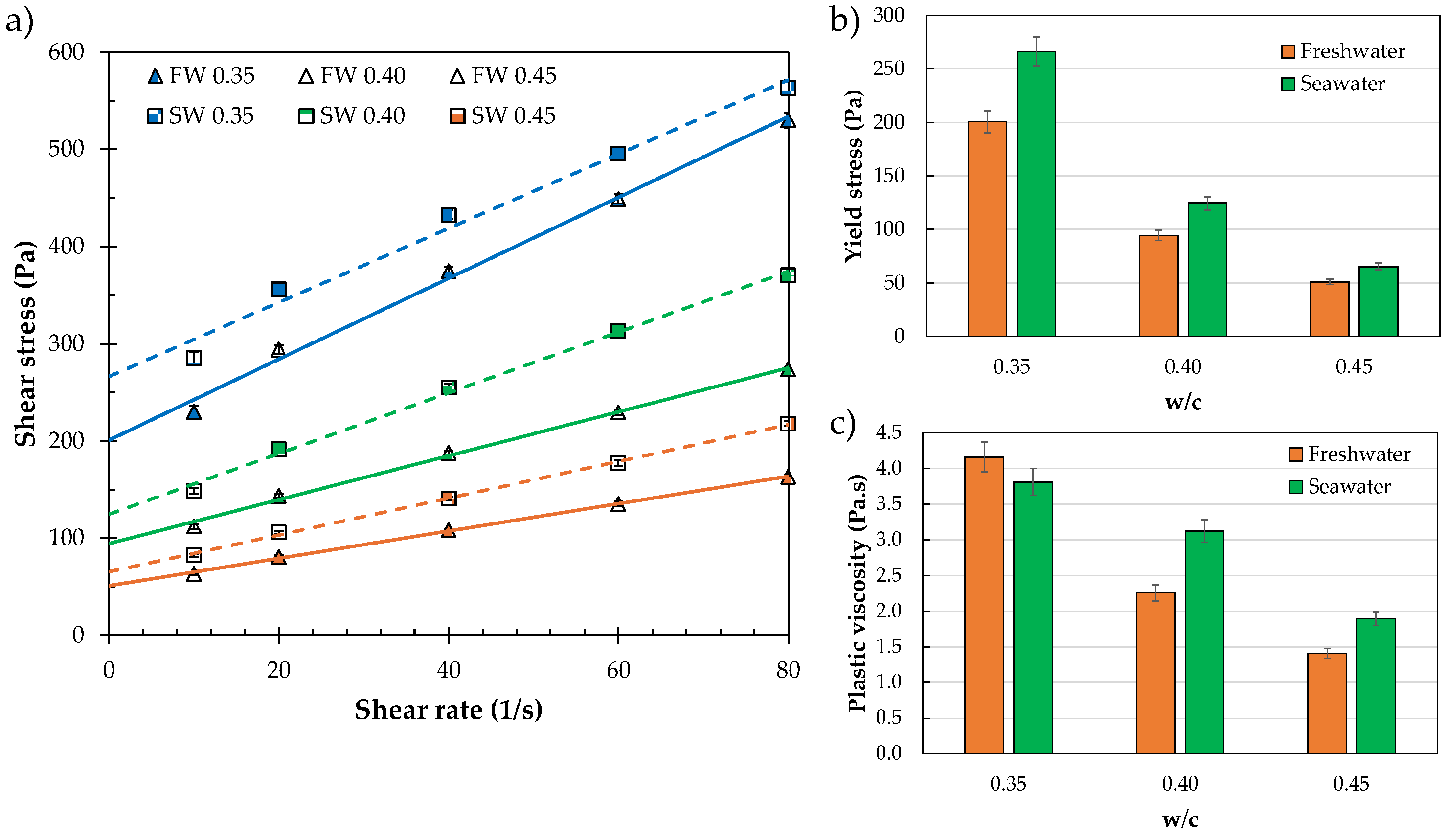

3.2. Results of Rheological Characterization

3.3. Printability in Underwater Conditions

3.4. Mechanical Performance of In-Air vs. Underwater Samples

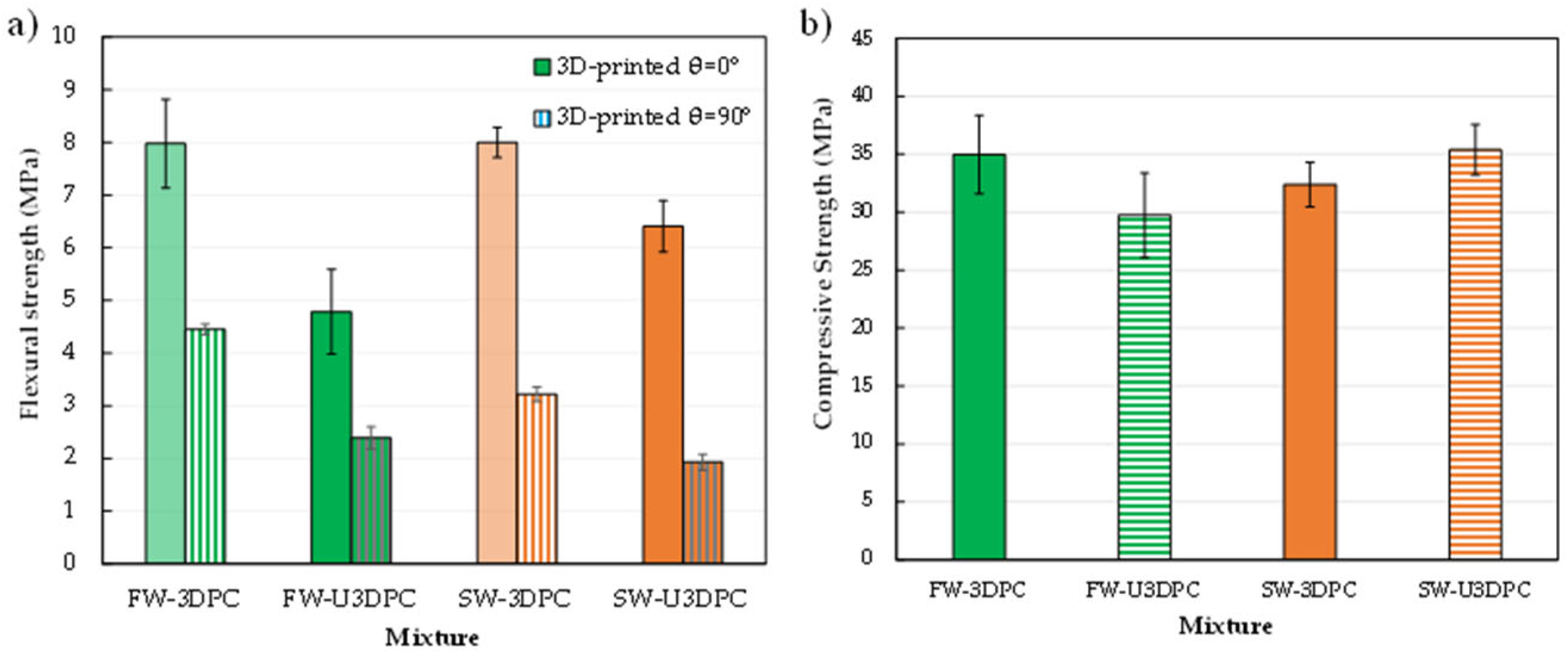

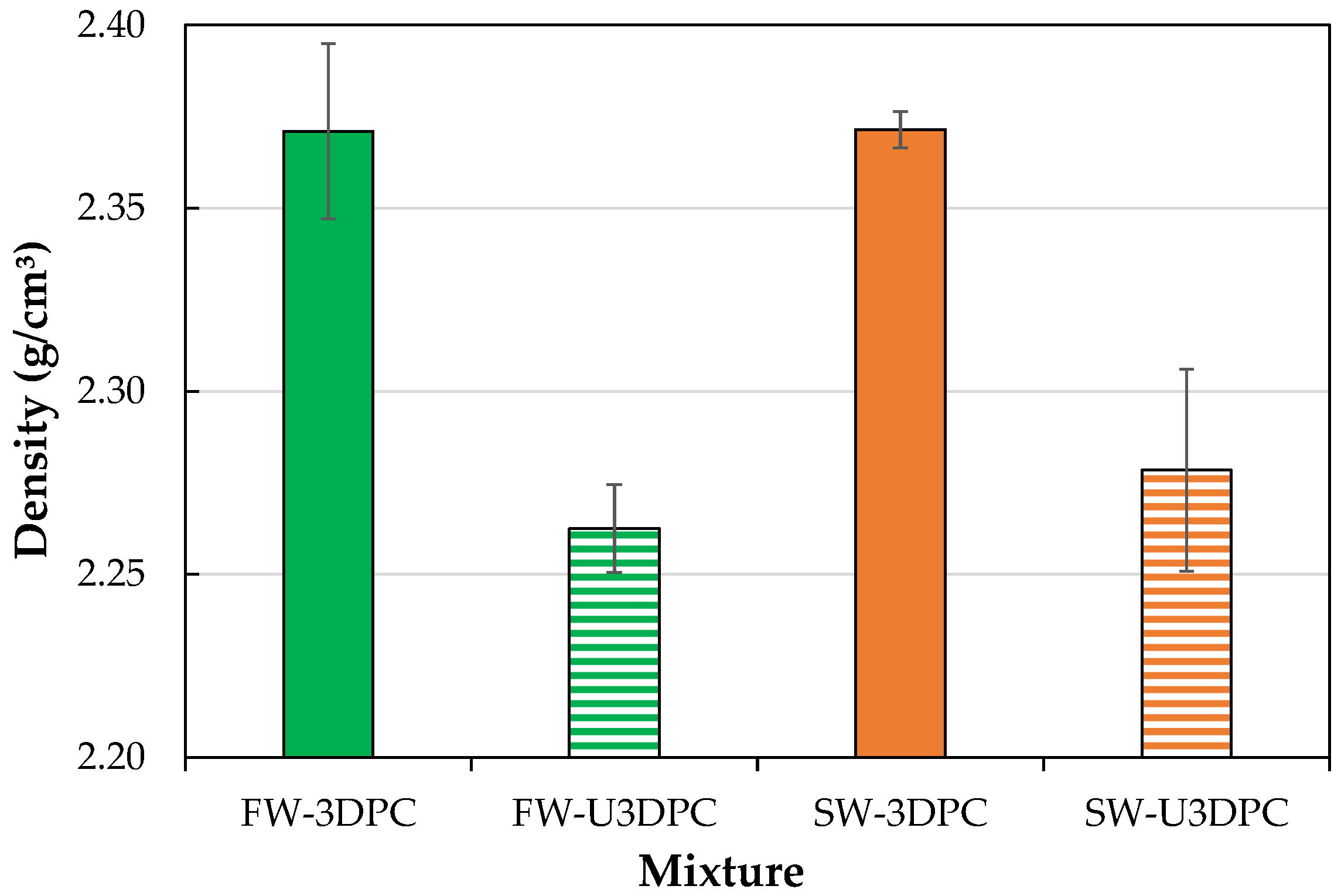

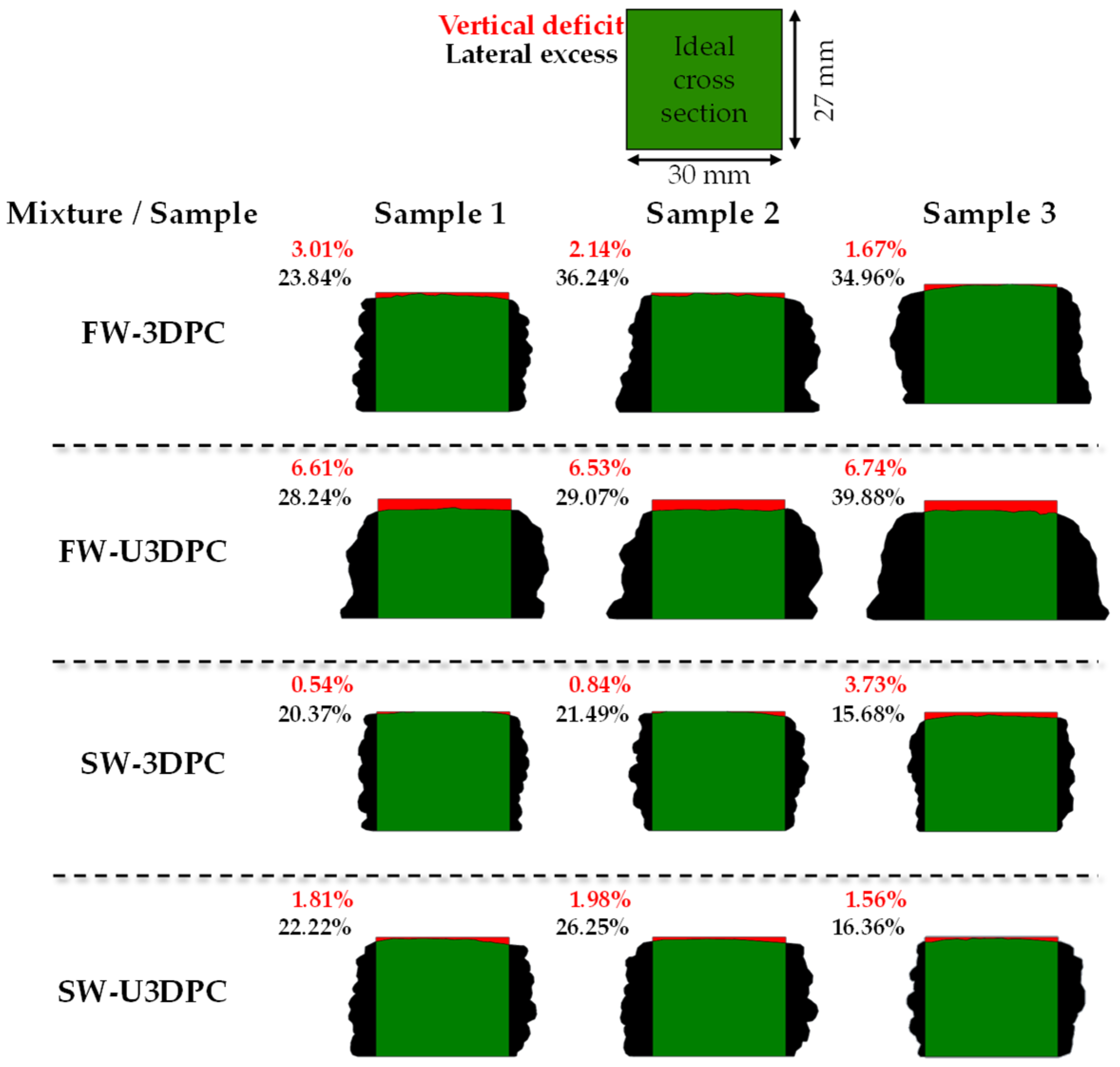

3.5. Hardened-State Density and Dimensional Accuracy

4. Considerations of Underwater 3D Printing of Concrete

5. Conclusions

- The successful formulation of printable mixtures for both in-air and underwater environments requires a balance between extrudability and buildability. For this purpose, rheological characterization established the appropriate dynamic yield stress and viscosity to enable smooth extrusion while maintaining adequate shape retention in a syringe-based printing system with the combined use of chemical admixtures, preventing bleeding, enhancing buildability, and improving shape retention in underwater conditions.

- Seawater substitution demonstrated minimal impact on yield stress but consistently increased plastic viscosity compared to freshwater mixtures. This viscosity increase contributed to improved dimensional stability without compromising the extrudability. The observed increase in hydration coupled with the increased viscosity are both beneficial to the underwater 3D printing environment.

- Mechanical testing revealed significant anisotropy in 3D-printed elements, with interfacial strength substantially lower than filament strength. In the case of compressive strength, results showed less sensitivity to printing environment and water type, with values ranging from 29.73 to 35.38 MPa at 28 days and no statistical difference between in-air and underwater samples, highlighting the potential of using seawater in 3D printing of concrete applications.

- Density measurements revealed 3.9–4.6% lower density in underwater-printed samples compared to in-air counterparts, independent of water type (freshwater or seawater). This reduction may indicate higher internal porosity resulting from water interaction during filament deposition. The increased internal porosity and compromised interfacial bonding in underwater conditions directly correlate with reduced flexural strength, highlighting the critical role of layer adhesion quality in mechanical performance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spanier, R.; Kuenzer, C. Marine Infrastructure Detection with Satellite Data—A Review. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugnot, A.B.; Mayer-Pinto, M.; Airoldi, L.; Heery, E.C.; Johnston, E.L.; Critchley, L.P.; Strain, E.M.A.; Morris, R.L.; Loke, L.H.L.; Bishop, M.J.; et al. Current and Projected Global Extent of Marine Built Structures. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for Coastal Management Economics and Demographics. Available online: https://coast.noaa.gov/states/fast-facts/economics-and-demographics.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Derouin, S. Engineers vs. Hurricanes: How to Protect People, Mitigate Damage. Available online: https://www.asce.org/publications-and-news/civil-engineering-source/civil-engineering-magazine/article/2024/05/engineers-vs-hurricanes-how-to-protect-people-mitigate-damage (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Braswell, A.E.; Leyk, S.; Connor, D.S.; Uhl, J.H. Creeping Disaster along the U.S. Coastline: Understanding Exposure to Sea Level Rise and Hurricanes through Historical Development. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- True Cost of Hurricanes: Case for a Comprehensive Understanding of Multihazard Building Damage. Available online: https://ascelibrary.org/doi/epdf/10.1061/%28ASCE%29LM.1943-5630.0000178 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Safapour, E.; Kermanshachi, S.; Rouhanizadeh, B. Prediction of Cost and Schedule Performance in Post-Hurricane Reconstruction of Transportation Infrastructure. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. The Economic Aftermath of Hurricanes Harvey and Irma: The Role of Federal Aid. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 61, 102301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New York City: The Big U. Available online: https://www.greenbuildermedia.com/blog/new-york-city-the-big-u (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Zanchettin, D.; Bruni, S.; Raicich, F.; Lionello, P.; Adloff, F.; Androsov, A.; Antonioli, F.; Artale, V.; Carminati, E.; Ferrarin, C.; et al. Sea-Level Rise in Venice: Historic and Future Trends (Review Article). Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 21, 2643–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida Sea Grant. Artificial Reef Deployment and Monitoring. Available online: https://www.flseagrant.org/fisheries/artificial-reef-deployment-and-monitoring/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Jiang, H.; Xie, Y.; Zeng, S.; Guo, S.; Chen, Z.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, D. Research on Lightweight Design Performance of Offshore Structures Based on 3D Printing Technology. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Feng, Z.; Sayed, U.; Li, H. Research on the Performance of Seawater Sea-Sand Concrete: A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 409, 133921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, A.; Ebead, U.; Suraneni, P.; Nanni, A. Fresh and Hardened Properties of Seawater-Mixed Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 190, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, R.S.; Archibald, N.; Comber, S.; Knights, A.M.; Thompson, R.C.; Firth, L.B. Partial Replacement of Cement for Waste Aggregates in Concrete Coastal and Marine Infrastructure: A Foundation for Ecological Enhancement? Ecol. Eng. 2018, 120, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhondy, T.; Remennikov, A.; Shiekh, M.N. Benefits of Using Sea Sand and Seawater in Concrete: A Comprehensive Review. Aust. J. Struct. Eng. 2019, 20, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, L.; Hu, Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y. Influential Factors on Mechanical Properties and Microscopic Characteristics of Underwater 3D Printing Concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 77, 107571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, M.; Salgues, M.; Souche, J.-C.; Weerdt, K.D.; Pioch, S. How to Improve the Bioreceptivity of Concrete Infrastructure Used in Marine Ecosystems? Literature Review for Mechanisms, Key Factors, and Colonization Effects. J. Coast. Res. 2023, 39, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkol-Finkel, S.; Hadary, T.; Rella, A.; Shirazi, R.; Sella, I. Seascape Architecture—Incorporating Ecological Considerations in Design of Coastal and Marine Infrastructure. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 120, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ido, S.; Shimrit, P.-F. Blue Is the New Green—Ecological Enhancement of Concrete Based Coastal and Marine Infrastructure. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 84, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Ji, G.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, G.; Mechtcherine, V.; Pan, J.; Wang, L.; Ding, T.; Duan, Z.; Du, S. Large-Scale 3D Printing Concrete Technology: Current Status and Future Opportunities. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 122, 104115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; McNally, C. Recent Developments on Low Carbon 3D Printing Concrete: Revolutionizing Construction through Innovative Technology. Clean. Mater. 2024, 12, 100251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, C.; Hédouin, L.; Lacorne, M.C.; Dalle, J.; Lapinski, M.; Blanc, P.; Nugues, M.M. Performance of Innovative Materials as Recruitment Substrates for Coral Restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2022, 30, e13625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korniejenko, K.; Gądek, S.; Dynowski, P.; Tran, D.H.; Rudziewicz, M.; Pose, S.; Grab, T. Additive Manufacturing in Underwater Applications. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, J.S. Applications of 3D Printing Technologies in Oceanography. Methods Oceanogr. 2016, 17, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, M.; Salgues, M.; Souche, J.-C.; Cunge, E.; Giraudel, C.; Paireau, O. Influence of the Intrinsic Characteristics of Cementitious Materials on Biofouling in the Marine Environment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhoud, B.; Perrot, A.; Picandet, V.; Rangeard, D.; Courteille, E. Underwater 3D Printing of Cement-Based Mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 214, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.-J.; Yang, J.-M.; Lee, H.; Kwon, H.-K. Comparison of Properties of 3D-Printed Mortar in Air vs. Underwater. Materials 2021, 14, 5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, L.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y. 3D Concrete Printing in Air and under Water: A Comparative Study on the Buildability and Interlayer Adhesion. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, F.; Ren, C. Optimization of 3D Printing Nozzle Structure and the Influence of Process Parameters on the Forming Performance of Underwater Concrete. Materials 2025, 18, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, O.; Lunsford, C.; Strait, J.; Nair, S.D. Breaking Barriers in Underwater Construction: A Two-Stage 3D Printing System with on-Demand Material Adaptation. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 164, 106306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, L.-C.; Chen, S.-G.; Liu, Y. Novel Strategy for Enhancing Rheological Properties and Interlayer Bonding in Underwater 3D Concrete Printing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 475, 141281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.G.; Zhang, G.-H. Feasibility of Underwater 3D Printing: Effects of Anti-Washout Admixtures on Printability and Strength of Mortar. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Liang, Q.; Li, P.; You, W.; Yin, X. Experimental Assessment on Printing Performance and Mechanical Properties of Underwater Self-Protecting 3D Printing Concrete. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2025, 23, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.-A.; Kim, W.-W.; Kim, S.-W.; Kwon, H.-K.; Lee, H.-J. Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Concrete with Coarse Aggregates and Polypropylene Fiber in the Air and Underwater Environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 378, 131184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C778; Standard Specification for Standard Sand. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM D1141-98(2021); Standard Practice for Preparation of Substitute Ocean Water. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM C1882/C1882M-24; Standard Specification for Anti-Washout Admixtures for Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- C494/C494M-17; Standard Specification for Chemical Admixtures for Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Roussel, N. Rheological Requirements for Printable Concretes. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 112, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C109/C109M-24; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic Cement Mortars (Using 2-in. or [50-mm] Cube Specimens). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Rodriguez, F.B.; Olek, J.; Moini, R.; Zavattieri, P.D.; Youngblood, J.P. Linking Solids Content and Flow Properties of Mortars to Their Three-Dimensional Printing Characteristics. ACI Mater. J. 2021, 118, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Hu, X.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, D. A Review on Seawater Sea-Sand Concrete: Mixture Proportion, Hydration, Microstructure and Properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 295, 123602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, W.; Yu, T.; Qu, F.; Tam, V.W.Y. Investigation on Early-Age Hydration, Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of Seawater Sea Sand Cement Mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 249, 118776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moini, R.; Olek, J.; Zavattieri, P.D.; Youngblood, J.P. Early-Age Buildability-Rheological Properties Relationship in Additively Manufactured Cement Paste Hollow Cylinders. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 131, 104538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mixture | w/c | s/c | Cement | Sand | Water | HRWRA | VMA | AWA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kg/m3 | kg/m3 | kg/m3 | mL/100 kg | mL/100 kg | mL/100 kg | |||

| FW-3DP | 0.32 | 0.75 | 1036.3 | 777.2 | 339.4 | 925 | 940 | 0 |

| FW-U3DP | 0.32 | 0.75 | 1036.2 | 777.1 | 339.3 | 925 | 470 | 525 |

| SW-3DP | 0.32 | 0.75 | 1036.3 | 777.2 | 339.4 | 925 | 940 | 0 |

| SW-U3DP | 0.32 | 0.75 | 1036.1 | 777.1 | 339.3 | 1110 | 470 | 525 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rodriguez, F.B.; Vugteveen, C.; Fross, X.; Wei, H.; Himmel, M.E.; Aday, A.N.; Svedruzic, D.; Kevern, J.T. 3D Printing of Cement-Based Materials Using Seawater for Simulated Marine Environments. Materials 2026, 19, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010093

Rodriguez FB, Vugteveen C, Fross X, Wei H, Himmel ME, Aday AN, Svedruzic D, Kevern JT. 3D Printing of Cement-Based Materials Using Seawater for Simulated Marine Environments. Materials. 2026; 19(1):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010093

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodriguez, Fabian B., Caiden Vugteveen, Xavier Fross, Hui Wei, Michael E. Himmel, Anastasia N. Aday, Drazenka Svedruzic, and John T. Kevern. 2026. "3D Printing of Cement-Based Materials Using Seawater for Simulated Marine Environments" Materials 19, no. 1: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010093

APA StyleRodriguez, F. B., Vugteveen, C., Fross, X., Wei, H., Himmel, M. E., Aday, A. N., Svedruzic, D., & Kevern, J. T. (2026). 3D Printing of Cement-Based Materials Using Seawater for Simulated Marine Environments. Materials, 19(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010093