Analyses of Stress-State-Dependent Ductile Damage and Fracture Behavior of Zirconium

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

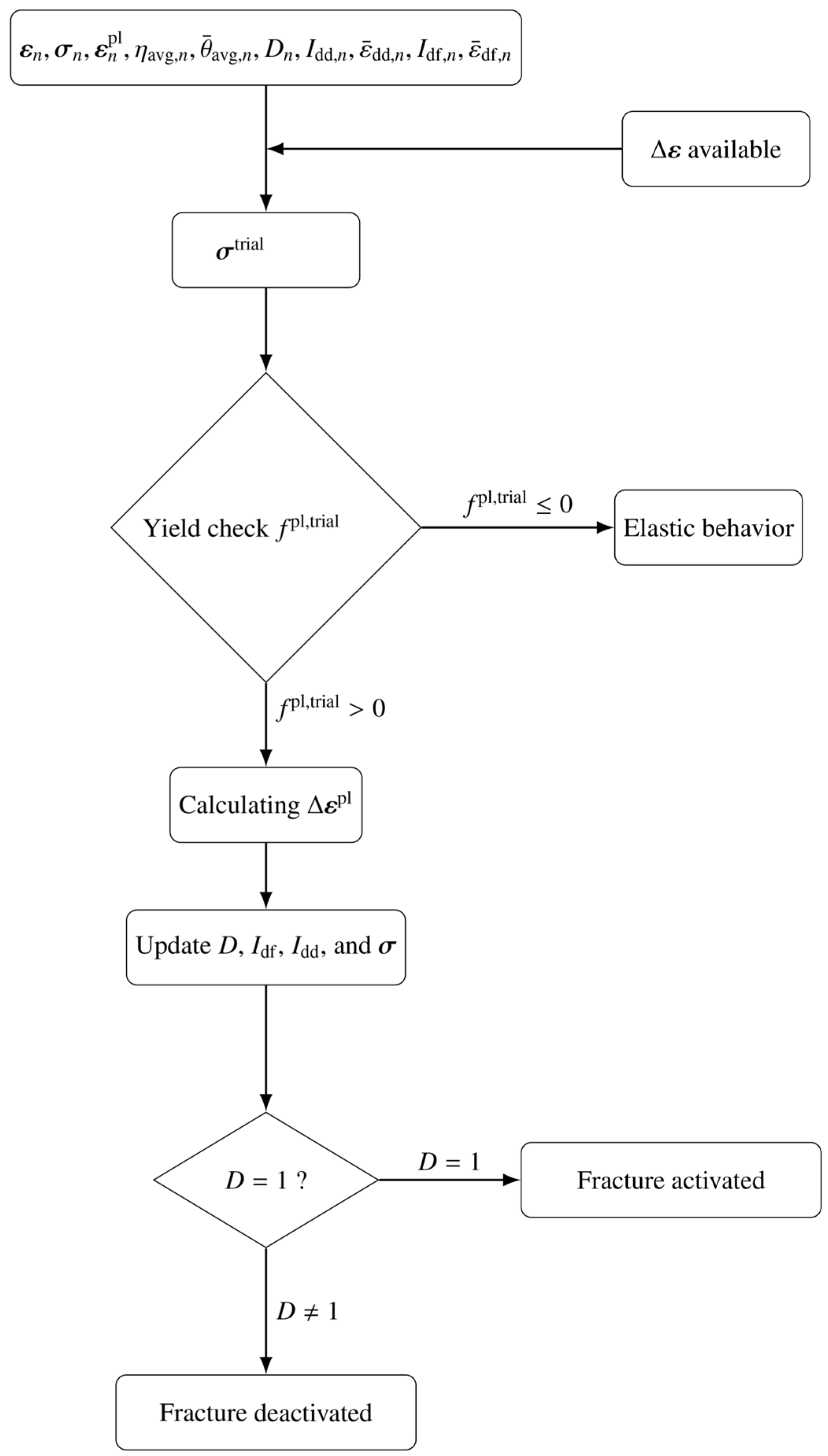

3. Material Models

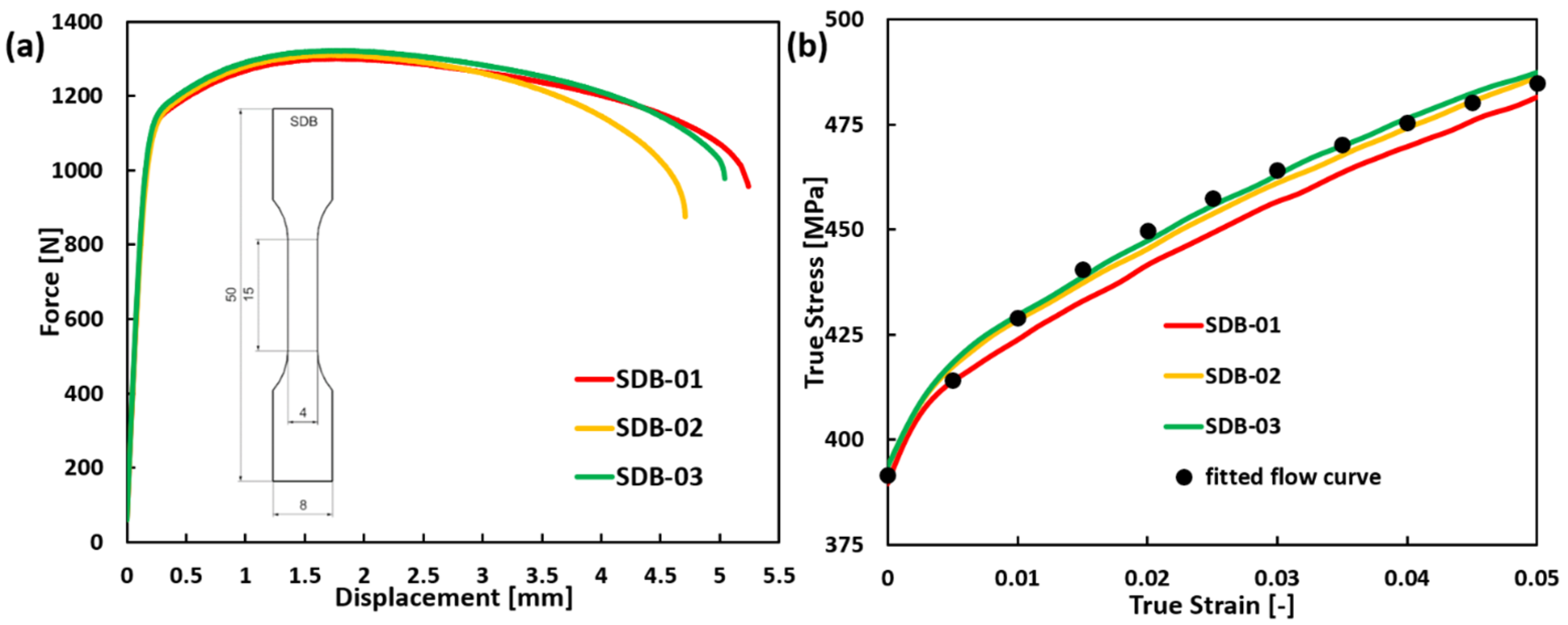

3.1. Elasto-Plasticity Model

3.2. Fracture Criterion

4. Results and Discussion

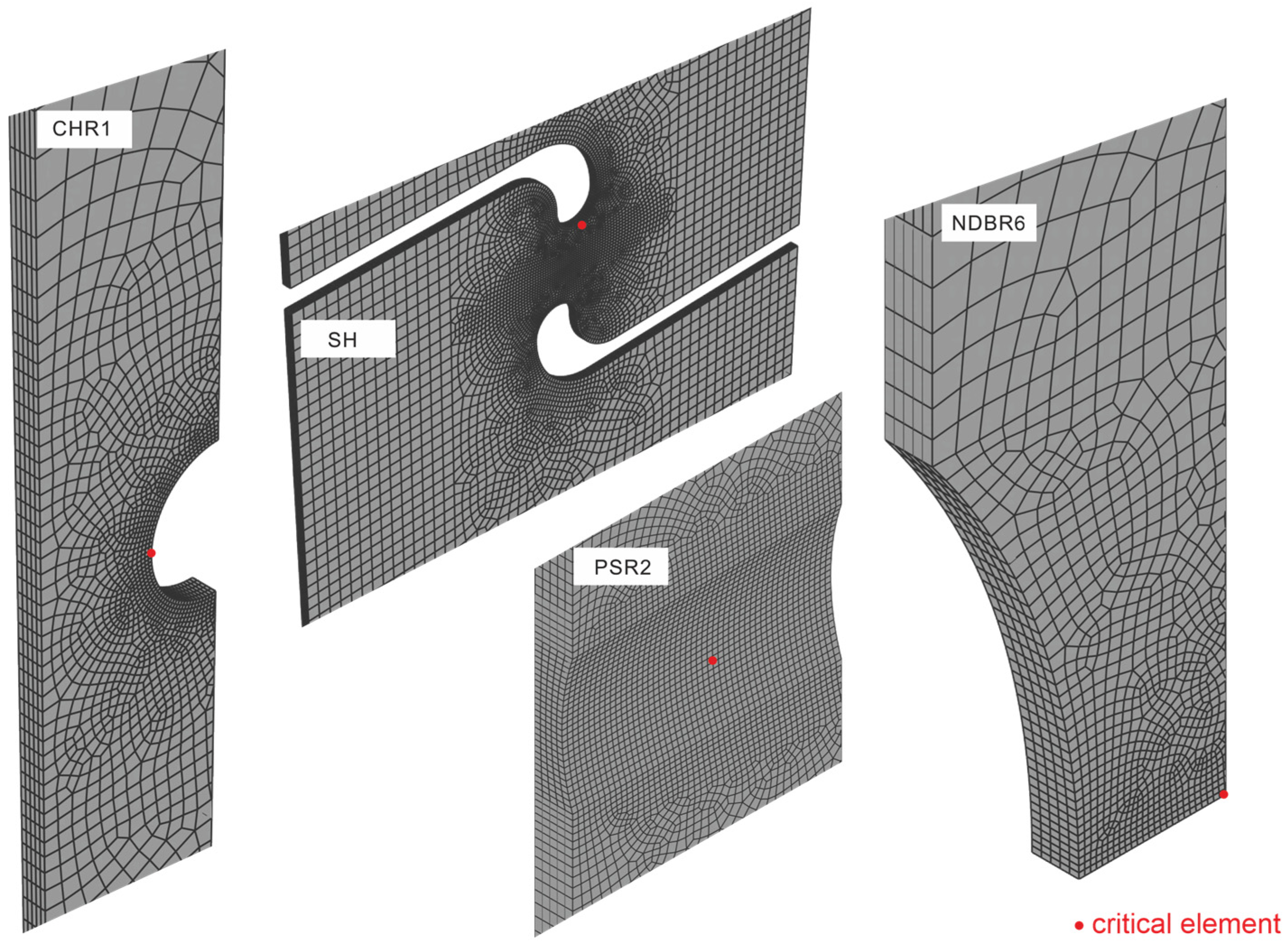

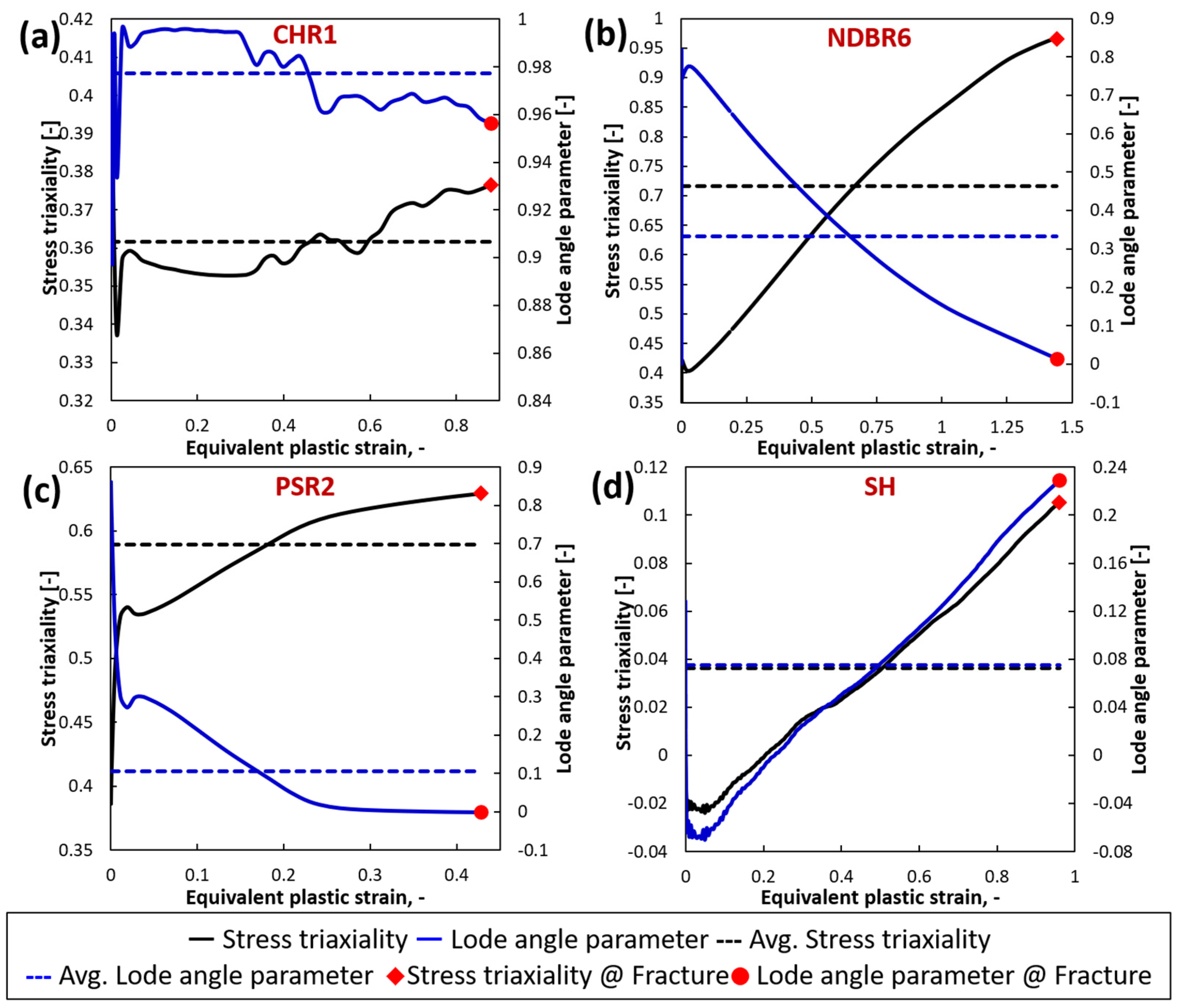

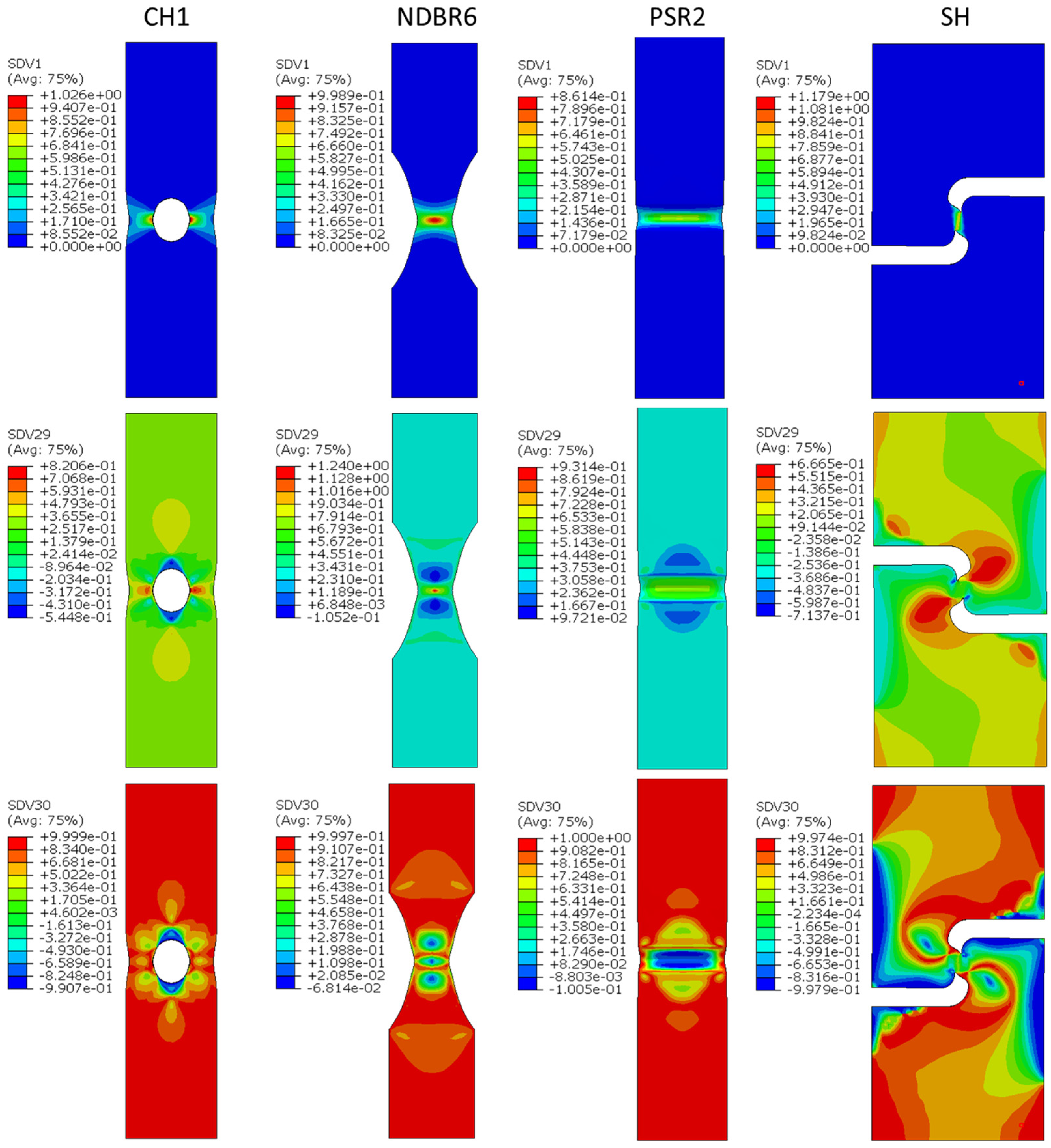

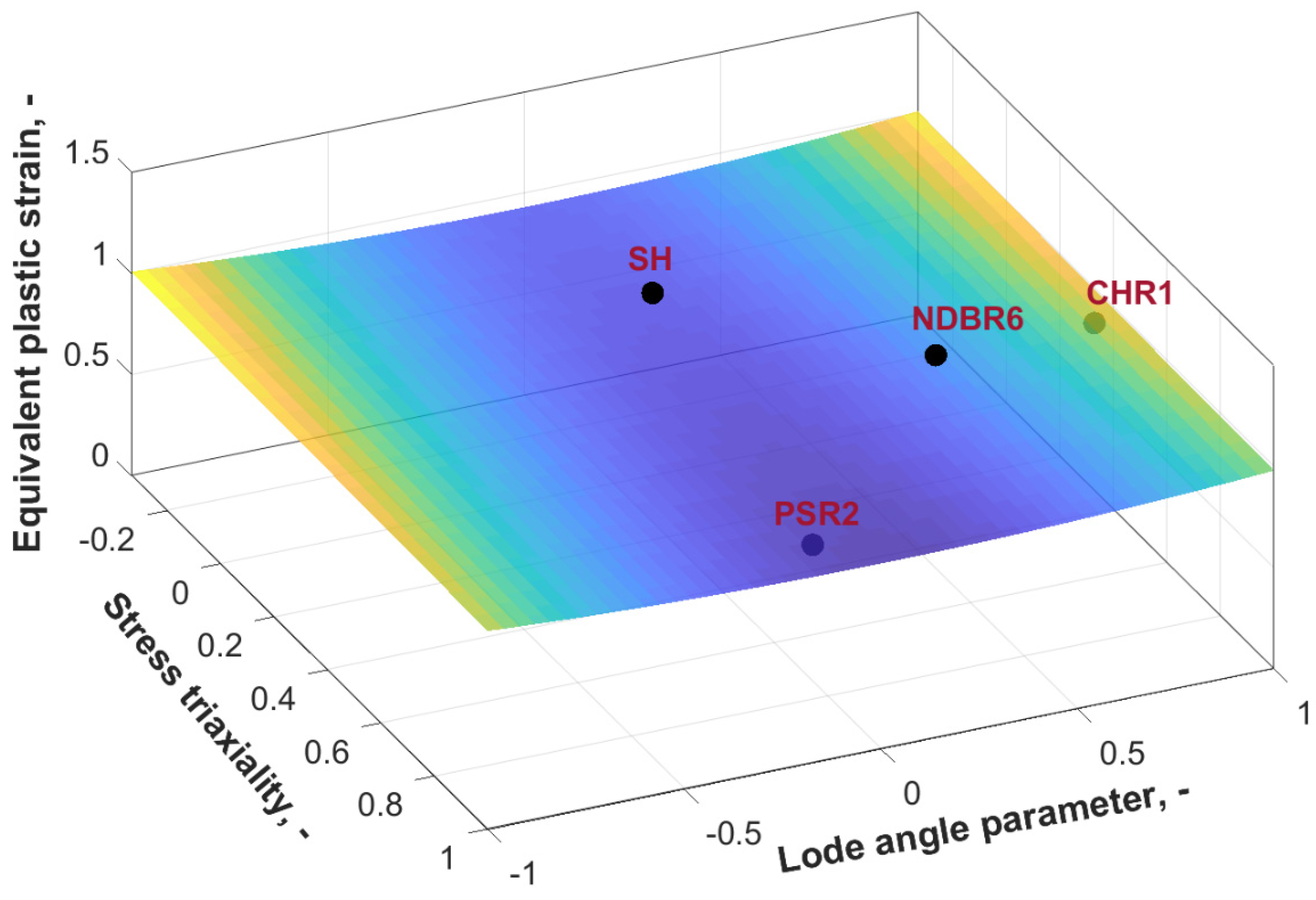

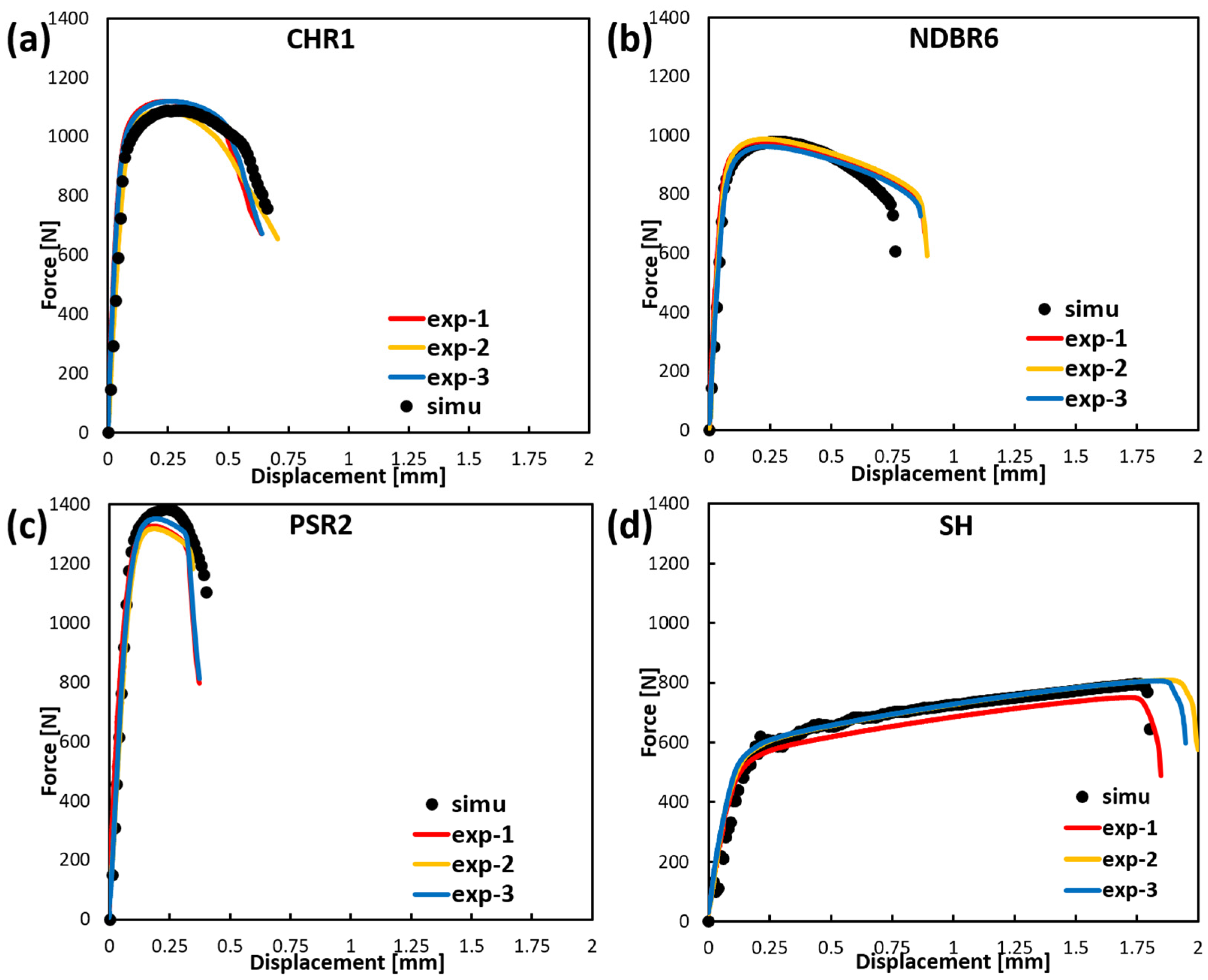

4.1. Calibration of the Model Parameters

4.2. Prediction of Fracture Behavior of Zirconium

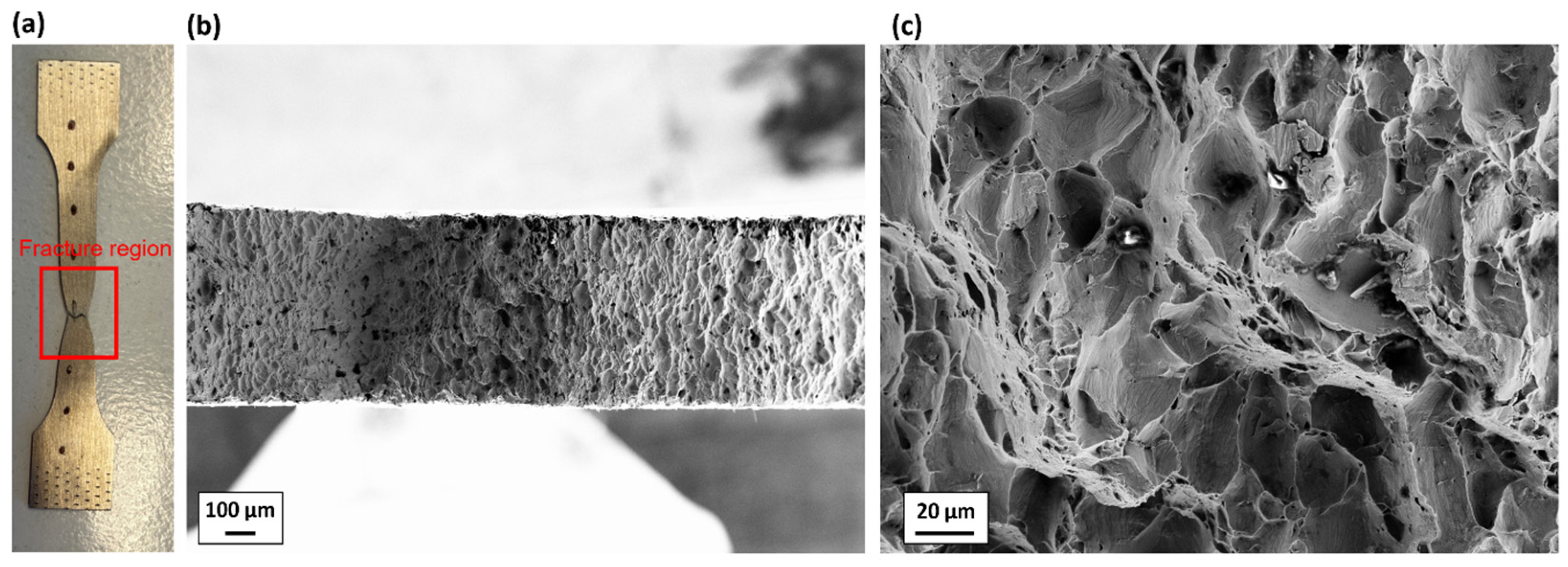

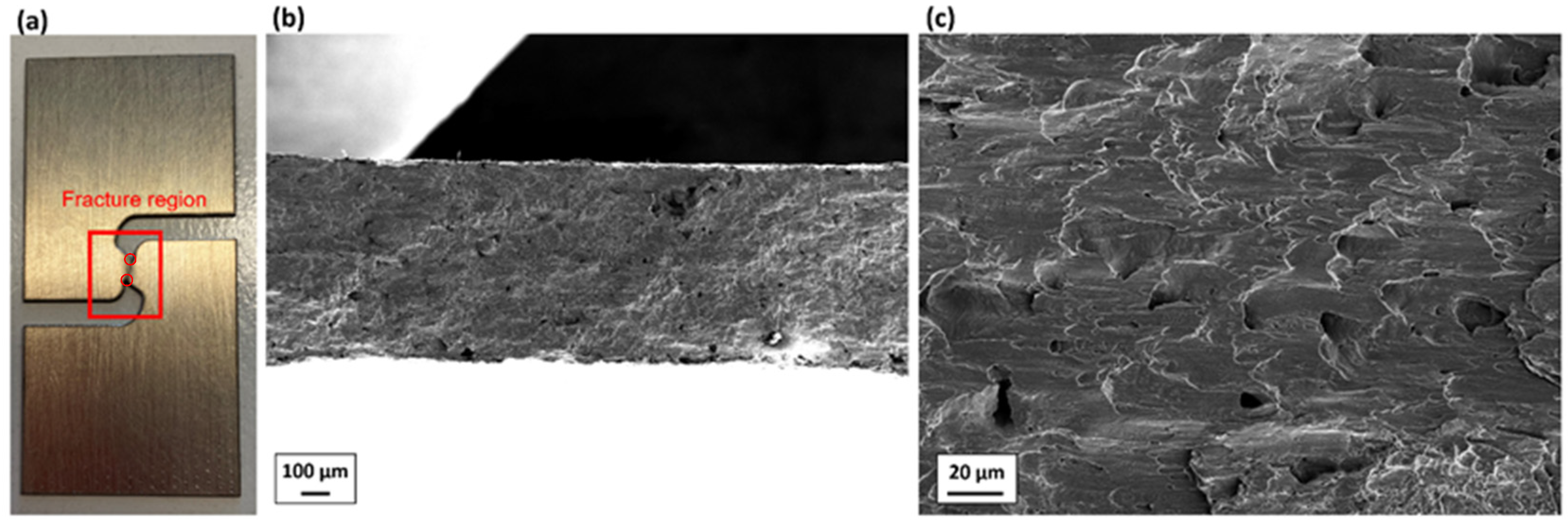

5. Fractography

6. Conclusions

- Characterizing fracture behavior covering a wide range of stress states by conducting uniaxial tensile tests on samples with different geometries. Necking was observed in the SDB sample, which is a typical feature for ductile fracture. Shear was observed at two tips of the crack in the pure shear sample.

- The elasto-plasticity behavior of Zr was modeled using the Yoon2014 asymmetric yield function, and the MBW fracture model was successfully calibrated using stress-state-dependent data extracted from FE simulations. The calibrated model reproduced the experimental force–displacement response for all specimen types with good accuracy.

- The fractographic analysis of the fracture surface reveals that the micro-damage mechanisms of the investigated Zr shift from a shear-dominated mechanism to a tension-dominated mechanism with increasing stress triaxiality.

- From a practical standpoint, the combined macroscopic and microscopic findings highlight which stress-state regimes are most detrimental for zirconium components. Low stress triaxiality shear states favor shear-band localization and early fracture, while high-triaxiality plane-strain conditions promote void growth and rapid loss of load-carrying capacity. Avoiding geometric features or loading configurations that impose these critical stress states can therefore reduce the risk of premature fracture.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MBW | Modified Bai-Wierzbicki model |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| LOCA | Loss of cooling agent |

| SDB | Standard dog bone |

| DIC | Digital image correlation |

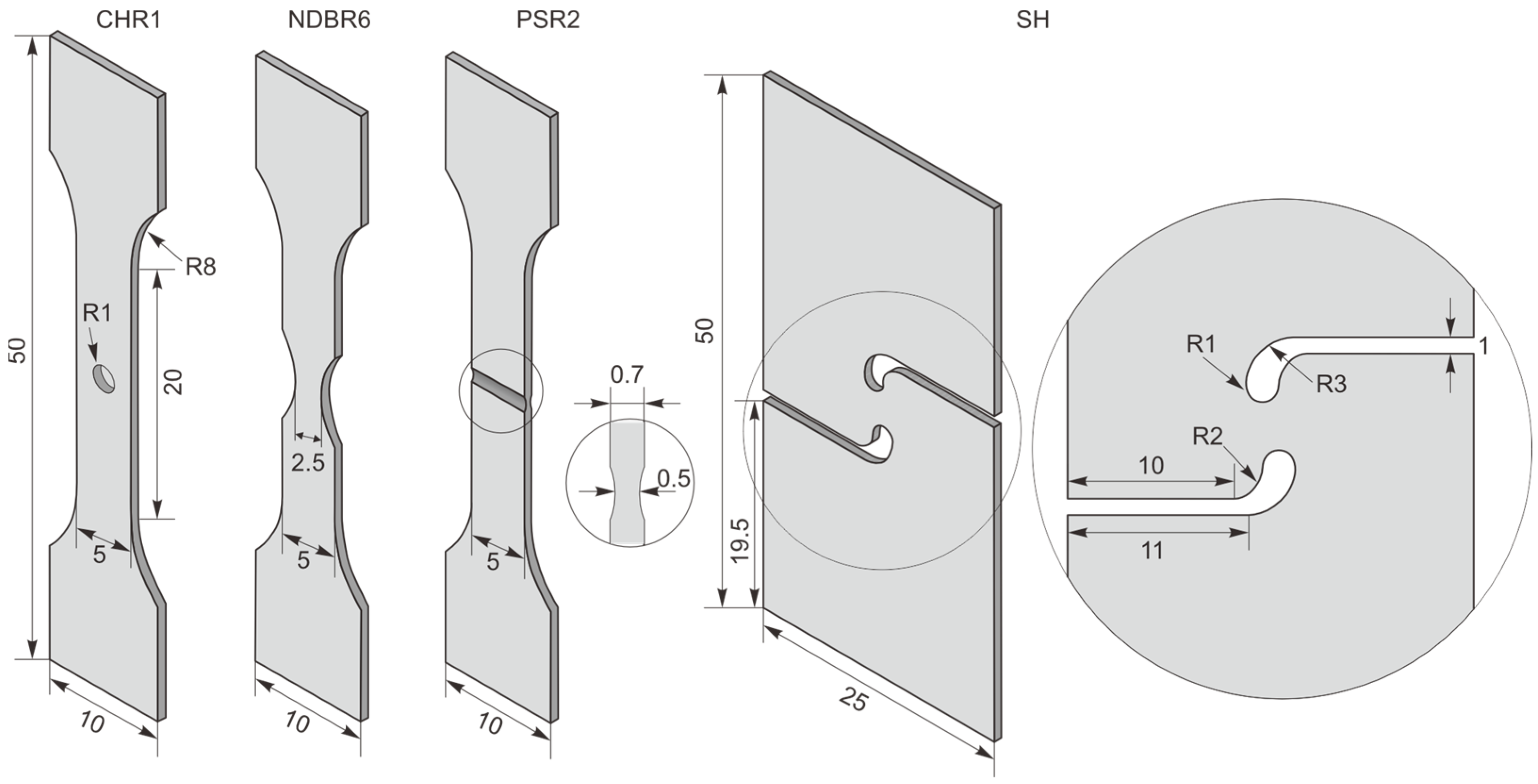

| CHR1 | Central hole samples with a radius of 1 mm |

| NDBR6 | Notched-dog bone samples with a notch radius of 6 mm |

| PSR2 | Plane strain samples with a radius of 2 mm |

| SH | Shear sample |

| SD | Strength differential |

| HCP | hexagonal close-packed |

| PEEQ | equivalent plastic strain |

| DIL | Ductile damage initiation locus |

| DFL | Ductile fracture locus |

| TolFun | Function convergence |

| TolX | Step size tolerance |

References

- Wang, W.; Lou, L.-Y.; Liu, K.-C.; Chen, T.-H.; Bi, Z.-J.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.-X. Structure and oxidation behavior of a chromium coating on Zr alloy cladding tubes deposited by high-speed laser cladding. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2024, 33, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Okamoto, K.; Pellegrini, M.; Tian, W.; Qiu, S.; Su, G. Model development for oxidation and degradation behavior of accident tolerant Cr coating on Zr alloy cladding under high temperature steam atmosphere. J. Nucl. Mater. 2024, 589, 154836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zuo, J.; Xiao, X.; Wu, K.; Zhang, J.; Liu, G.; Sun, J. High-temperature steam oxidation behavior and failure mechanisms of Al alloyed Cr coatings on Zr-4 alloy. Corros. Sci. 2024, 230, 111898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeom, H.; Johnson, G.; Maier, B.; Dabney, T.; Sridharan, K. High temperature oxidation of cold spray Cr-coated accident tolerant zirconium-alloy cladding with Nb diffusion barrier layer. J. Nucl. Mater. 2024, 588, 154822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Geng, D.; Sun, Q.; Song, Z.; Sun, J. Steam oxidation of Cr-coated zirconium alloy claddings at 1200 °C: Kinetics transition and failure mechanism of Cr coatings. J. Nucl. Mater. 2023, 586, 154684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.R. A constitutive model and data for metals subjected to large strains, high strain rates and high temperatures. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Ballistics, The Hague, The Netherlands, 19–21 April 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, G.R.; Cook, W.H. Fracture characteristics of three metals subjected to various strains, strain rates, temperatures and pressures. Eng. Fract. Mech. 1985, 21, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wu, Z.; Bao, C.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, G. Investigation of the tensile fracture behavior and failure criteria of domestic Zr-2.5 Nb alloy under different stress triaxiality conditions. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2025, 318, 110991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Ding, F.; Chen, F.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, J. Study on the fracture behaviour of 6061 aluminum alloy extruded tube during different stress conditions. Crystals 2023, 13, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Cui, G.; Li, Y.; Bao, C. Investigation on the dynamic fracture behavior of A508-III steel based on Johnson–Cook model. Int. J. Fract. 2023, 243, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, E.; Cavusoglu, O.; Güral, A. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Strain Rate Dependent Flow and Fracture Behavior of 6181A-T4 Alloy Using the Johnson–Cook Model. Crystals 2025, 15, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wierzbicki, T. A new model of metal plasticity and fracture with pressure and Lode dependence. Int. J. Plast. 2008, 24, 1071–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Sharaf, M.; Archie, F.; Münstermann, S. A hybrid approach for modelling of plasticity and failure behaviour of advanced high-strength steel sheets. Int. J. Damage Mech. 2013, 22, 188–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Shen, F.; Fekete, M.; Ramesh, D.J.; Schneider, J.; Münstermann, S. Investigation of the failure mechanisms of Zr alloy with Cr2AlC coatings using in-situ bending tests: Experiments and simulations. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 167, 108964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Zhu, L.; Shen, F.; Münstermann, S. Dual-scale Investigation of Temperature-Dependent Plasticity and Damage of DP780. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 302, 110565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Jiang, Z.; Shen, F.; Tekkaya, B.; Münstermann, S. Cross-Scale Study of DP780 Steel: From Crystal Plasticity Modeling to Failure and Formability Prediction. Steel Res. Int. 2025, 96, 2500266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Fehlemann, N.; Herrig, T.; Lenz, D.; Könemann, M.; Bergs, T.; Münstermann, S. Forming Limit of Dual Phase Steel: An Experimental and Numerical Investigation. In International Conference on the Technology of Plasticity; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Volume 96. [Google Scholar]

- Khandelwal, H.; Singh, R.N.; Bind, A.; Sunil, S.; Chakravartty, J.; Ghosh, A.; Dhandharia, P.; Bhachawat, D.; Shekhar, R.; Kumar, S.J. Tensile properties and fracture toughness of Zr–2.5 Nb alloy pressure tubes of IPHWR220. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2015, 293, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Ma, F.; Zhang, J.; Du, D.; Tian, H.; Xu, Q.; Zhou, J.; Gong, W. Effect of hydride orientation on tensile properties and crack formation in zirconium alloy cladding tubes. J. Nucl. Mater. 2024, 596, 155120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilloud, D.; Pierson, J.F.; Rousselot, C.; Palmino, F. Substrate effect on the formation of ω-phase in sputtered zirconium films. Scr. Mater. 2025, 53, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, M.; Wierzbicki, T. On mechanical response of Zircaloy-4 under a wider range of stress states: From uniaxial tension to uniaxial compression. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2020, 206, 198–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed-Hill, R. Role of deformation twinning in determining the mechanical properties of metals. In The Inhomogeneity of Plastic Deformation; ASM Seminar: Materials Park, OH, USA, 1973; pp. 285–311. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, X.; Li, M.; Boger, R.; Agnew, S.; Wagoner, R. Hardening evolution of AZ31B Mg sheet. Int. J. Plast. 2007, 23, 44–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ding, J.; Fan, Z.; Tian, L.; Li, M.; Lu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, E.; Li, J.; Shan, Z. Tension–compression asymmetry in amorphous silicon. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Gerke, S.; Brünig, M. Novel uniaxial and biaxial reverse experiments for material parameter identification in an advanced anisotropic cyclic plastic-damage model. Mech. Mater. 2025, 205, 105249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzig, W.; Richmond, O. The effect of pressure on the flow stress of metals. Acta Metall. 1984, 32, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazacu, O.; Barlat, F. A criterion for description of anisotropy and yield differential effects in pressure-insensitive metals. Int. J. Plast. 2004, 20, 2027–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazacu, O.; Plunkett, B.; Barlat, F. Orthotropic yield criterion for hexagonal closed packed metals. Int. J. Plast. 2006, 22, 1171–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, F.; Hamasaki, H.; Uemori, T. A user-friendly 3D yield function to describe anisotropy of steel sheets. Int. J. Plast. 2013, 45, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Gao, X.; Sobotka, J.C.; Webler, B.A.; Cockeram, B.V. Modeling the tension–compression asymmetric yield behavior of β-treated Zircaloy-4. J. Nucl. Mater. 2014, 451, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Yoon, J.W. Analytical description of an asymmetric yield function (Yoon2014) by considering anisotropic hardening under non-associated flow rule. Int. J. Plast. 2021, 140, 102978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.W.; Lou, Y.; Yoon, J.; Glazoff, M.V. Asymmetric yield function based on the stress invariants for pressure sensitive metals. Int. J. Plast. 2014, 56, 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Shen, F.; Münstermann, S. Constitutive modeling of temperature and strain rate effects on anisotropy and strength differential properties of metallic materials. Mech. Mater. 2023, 184, 104714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandre, S.; Kotkunde, N.; Suresh, K.; Singh, S.K. Investigation of fracture forming limits of dual phase steel under warm incremental forming process. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2024, 18, 2131–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besson, J. Continuum models of ductile fracture: A review. Int. J. Damage Mech. 2010, 19, 3–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineau, A.; Benzerga, A.A.; Pardoen, T. Failure of metals I: Brittle and ductile fracture. Acta Mater. 2016, 107, 424–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzerga, A.A.; Leblond, J.-B.; Needleman, A.; Tvergaard, V. Ductile failure modeling. Int. J. Fract. 2016, 201, 29–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekkaya, A.; Bouchard, P.-O.; Bruschi, S.; Tasan, C. Damage in metal forming. CIRP Ann. 2020, 69, 600–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Könemann, M.; Dölz, M.; Münstermann, S. A new method for the toughness assessment of mobile crane components based on damage mechanics. Steel Constr. 2022, 15, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, F.; Zheng, J.; Münstermann, S.; Li, T.; Han, W.; Huang, S. Ductility prediction of HPDC aluminum alloy using a probabilistic ductile fracture model. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2022, 119, 103381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Shen, F.; Sampathkumar, S.R.; Münstermann, S. Modeling Strain Hardening of Metallic Materials with Sigmoidal Function Considering Temperature and Strain Rate Effects. Materials 2024, 17, 3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Li, X.; Di, Y.; Brinnel, V.; Lian, J.; Münstermann, S. Extension of the modified Bai-Wierzbicki model for predicting ductile fracture under complex loading conditions. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2017, 40, 2152–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Wierzbicki, T. On the cut-off value of negative triaxiality for fracture. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2005, 72, 1049–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pütz, F.; Shen, F.; Könemann, M.; Münstermann, S. The differences of damage initiation and accumulation of DP steels: A numerical and experimental analysis. Int. J. Fract. 2020, 226, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Liu, W.; Könemann, M.; Yuan, G.; Wang, G.; Münstermann, S.; Lian, J. Local formability of medium-Mn steel. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 299, 117368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekkaya, B.; Meurer, M.; Dölz, M.; Könemann, M.; Münstermann, S.; Bergs, T. Modeling of microstructural workpiece rim zone modifications during hard machining. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2023, 311, 117815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekkaya, B.; Wu, J.; Dölz, M.; Lian, J.; Münstermann, S. Coupled chemical–mechanical damage modeling of hydrogen-induced material degradation. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2025, 314, 110751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | E | A80 | ϑ * | |||

| Zirconium | 400 MPa | 89 GPa | 445 MPa | 25% | 0.34 | |

| Swift hardening law | ||||||

| Material | B | n | ||||

| Zirconium | 646 MPa | 0.0067 | 0.1 | |||

| Sample | PEEQ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CHR1 | 0.362 | 0.977 | 0.881 |

| NDBR6 | 0.716 | 0.333 | 1.442 |

| PSR2 | 0.589 | 0.106 | 0.428 |

| SH | 0.0362 | 0.0747 | 0.960 |

| 1 | 0.02098 | 0.9256 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pan, B.; Zhu, L.; Wei, Z.; Tekkaya, B.; Stebner, S.; Münstermann, S. Analyses of Stress-State-Dependent Ductile Damage and Fracture Behavior of Zirconium. Materials 2026, 19, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010081

Pan B, Zhu L, Wei Z, Tekkaya B, Stebner S, Münstermann S. Analyses of Stress-State-Dependent Ductile Damage and Fracture Behavior of Zirconium. Materials. 2026; 19(1):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010081

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Boyu, Lianghui Zhu, Zhichao Wei, Berk Tekkaya, Sophie Stebner, and Sebastian Münstermann. 2026. "Analyses of Stress-State-Dependent Ductile Damage and Fracture Behavior of Zirconium" Materials 19, no. 1: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010081

APA StylePan, B., Zhu, L., Wei, Z., Tekkaya, B., Stebner, S., & Münstermann, S. (2026). Analyses of Stress-State-Dependent Ductile Damage and Fracture Behavior of Zirconium. Materials, 19(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010081