Purification of Isosorbide via Ion Exchange Resin for High-Performance Bio-Based Polycarbonate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Ion Exchange Resin Pre-Treatment

2.3. Purify Isosorbide by Ion Exchange Chromatography

2.4. Adsorption Kinetics Studies

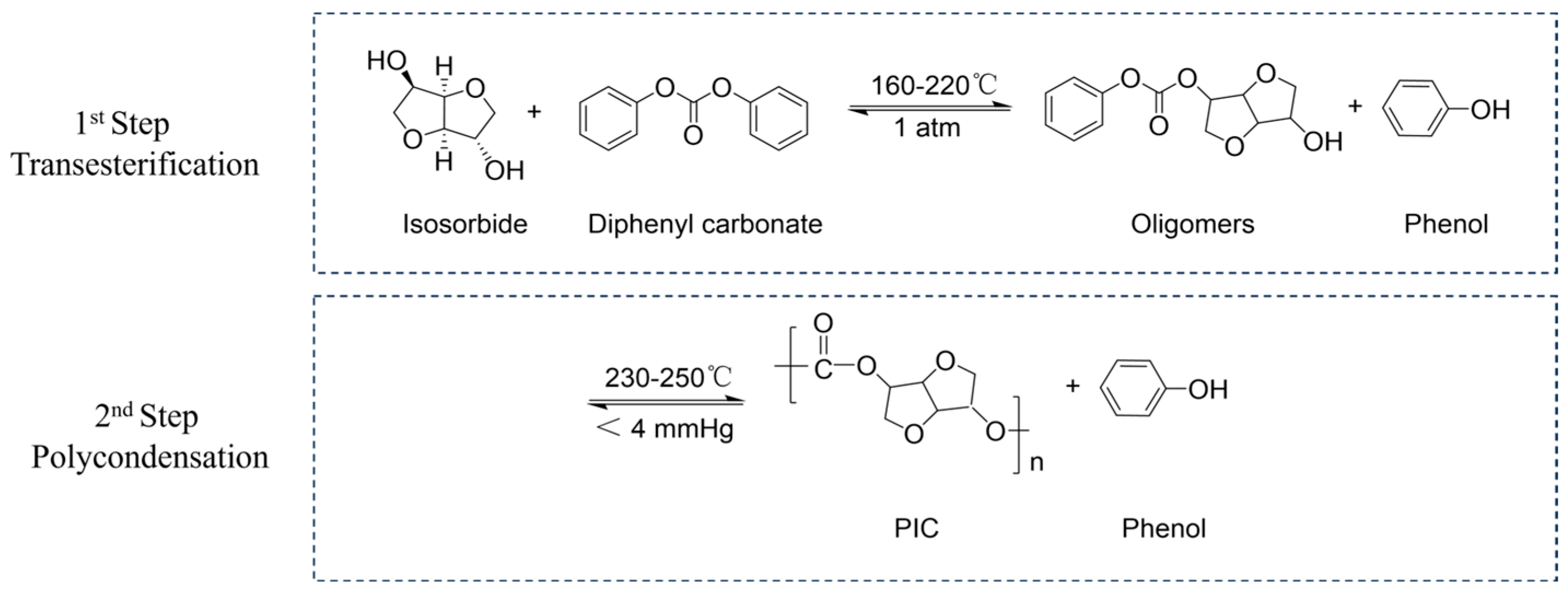

2.5. Synthetic Isosorbide-Based Polycarbonate (PIC)

2.6. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. FTIR Spectra and HPLC Chromatogram of ISB Before and After Purification

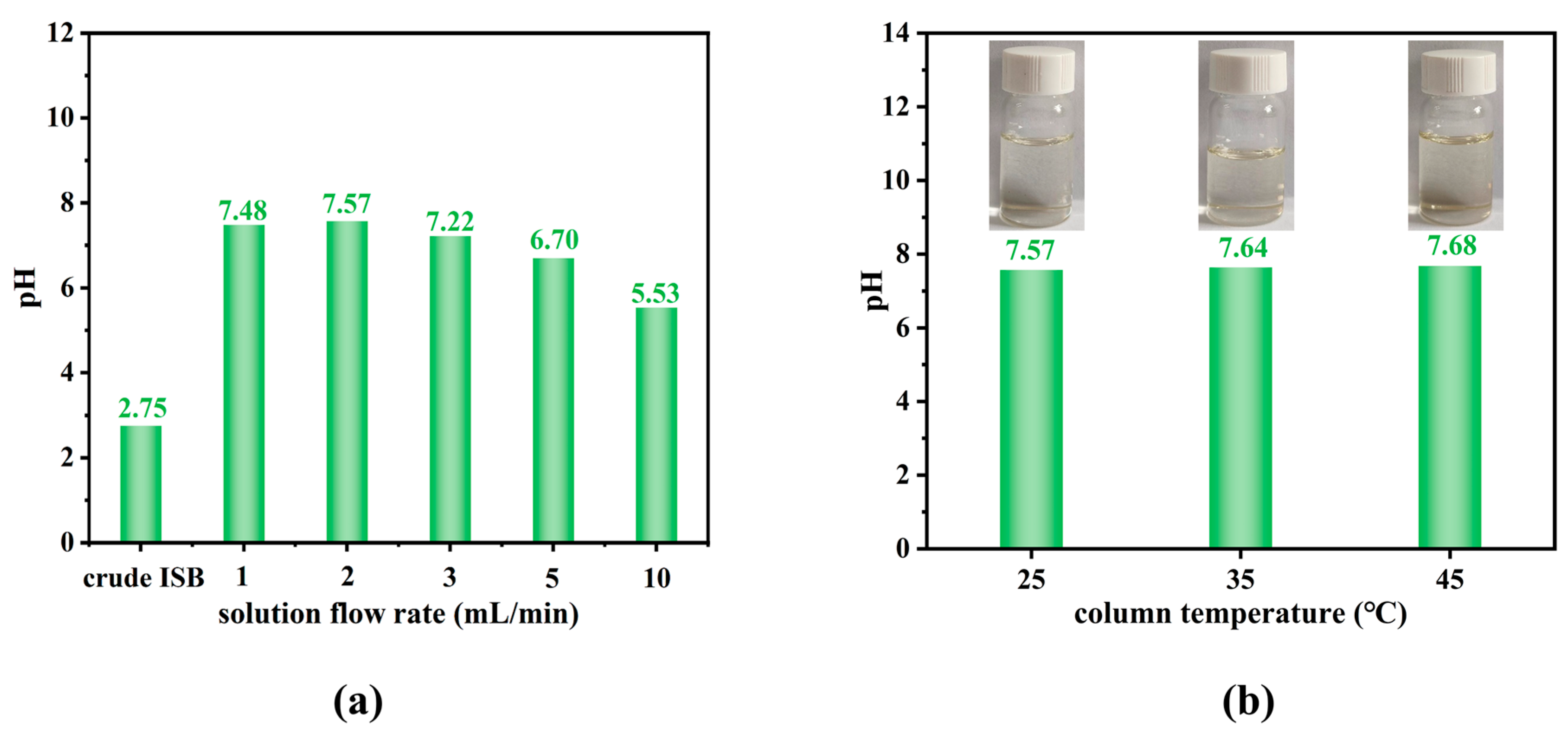

3.2. The Influence of Chromatographic Parameters on Purification Efficiency

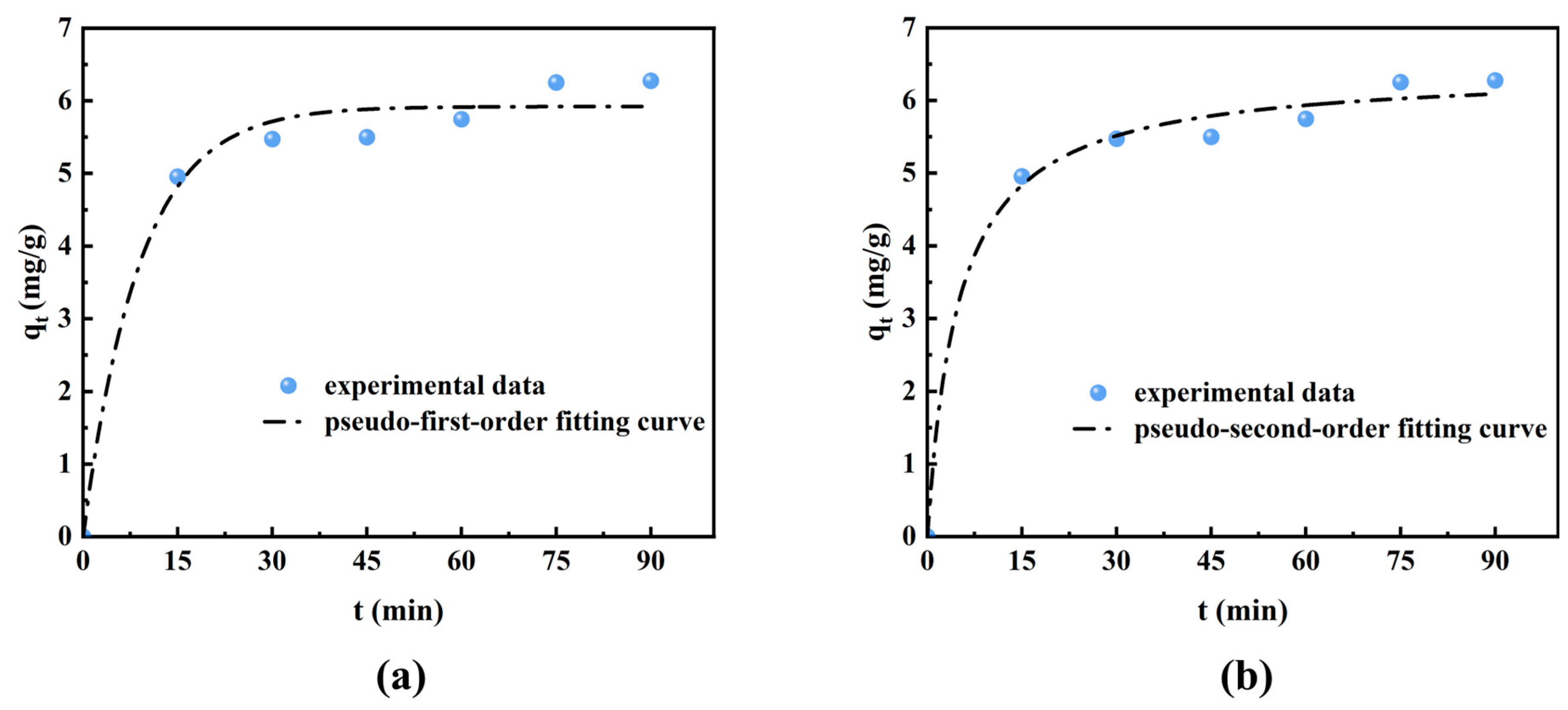

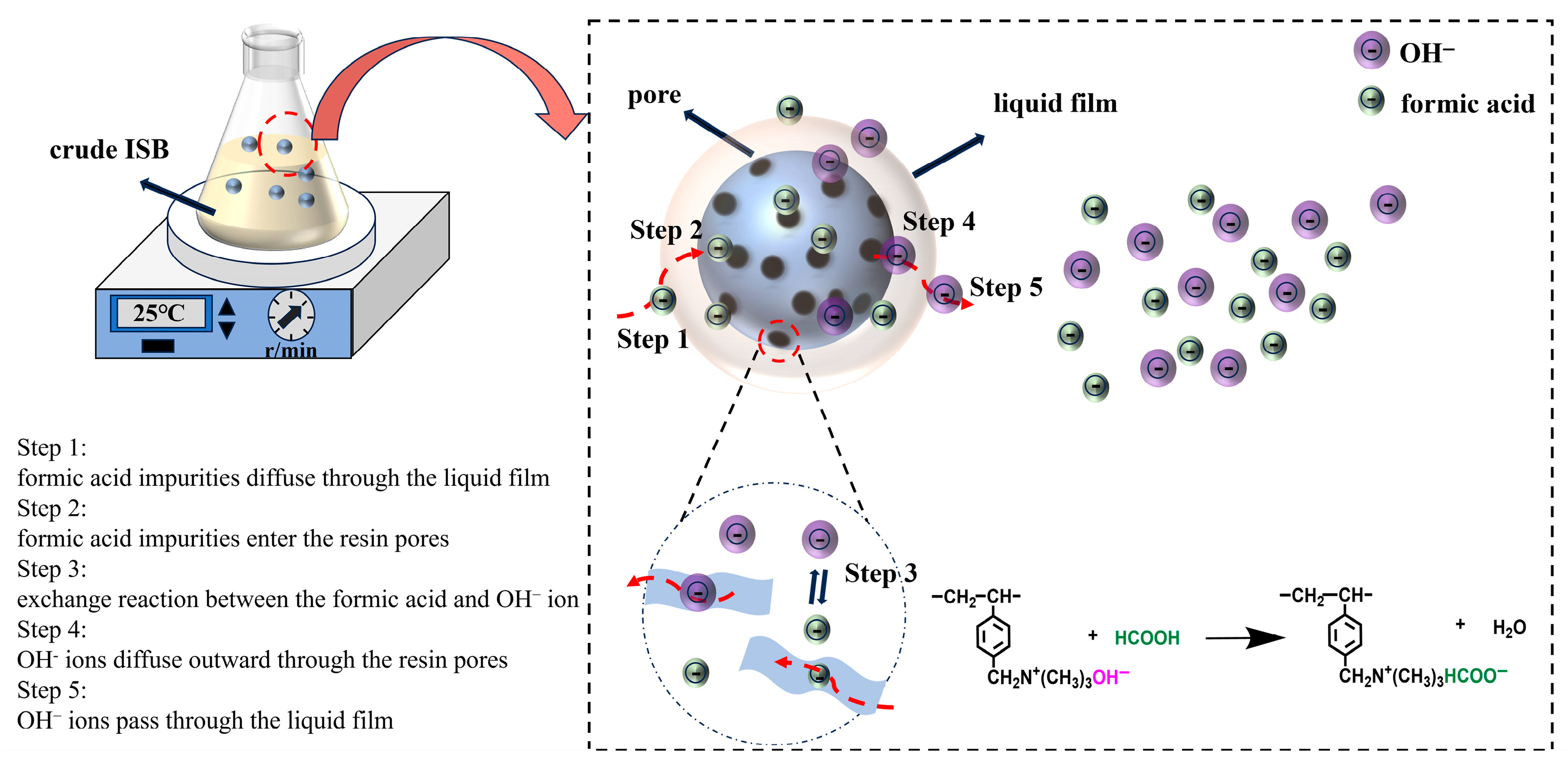

3.3. Adsorption Kinetics

3.4. Moving Boundary Model

3.5. Synthesis of High-Performance PIC

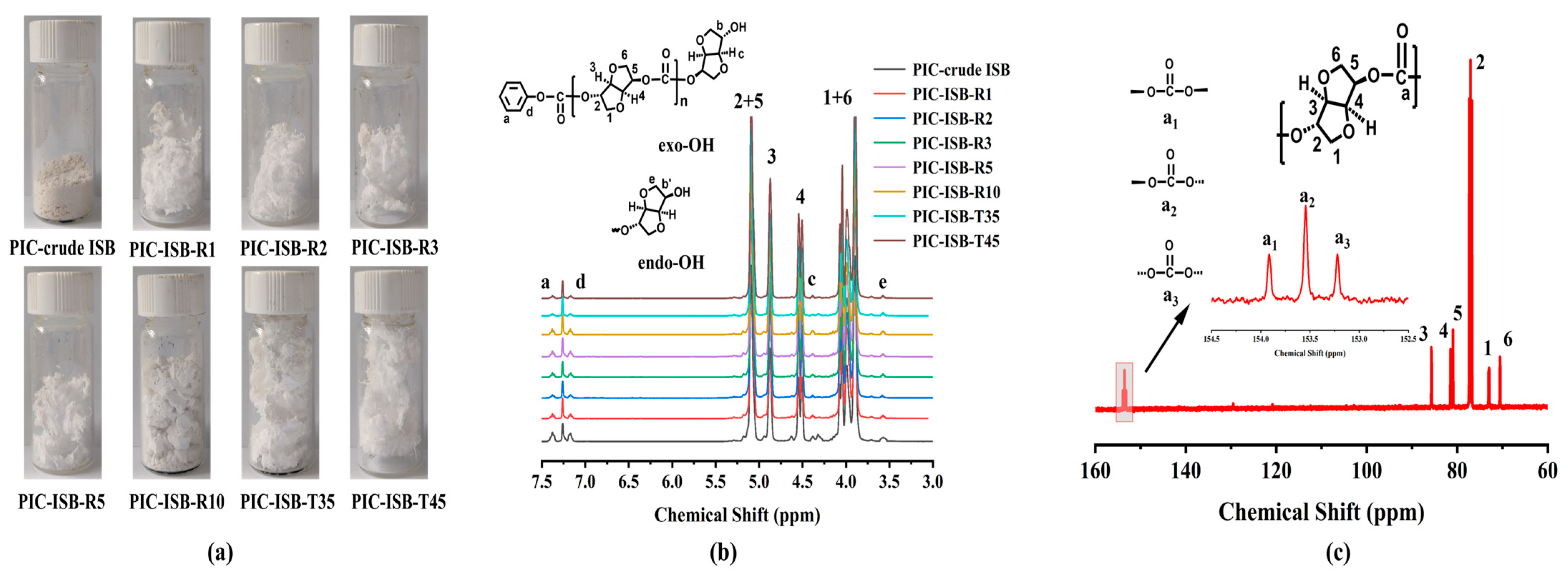

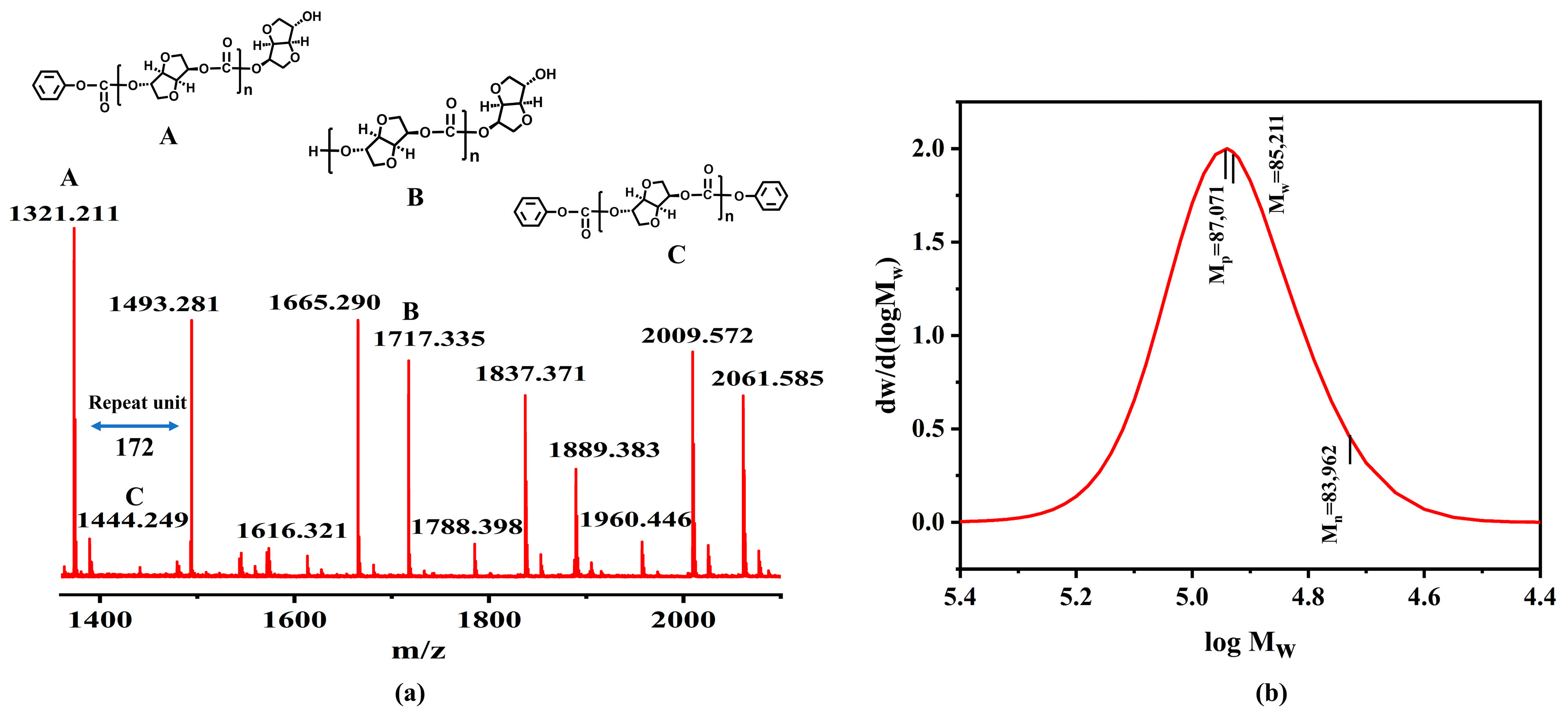

3.5.1. Molecular Weight and Chemical Structure

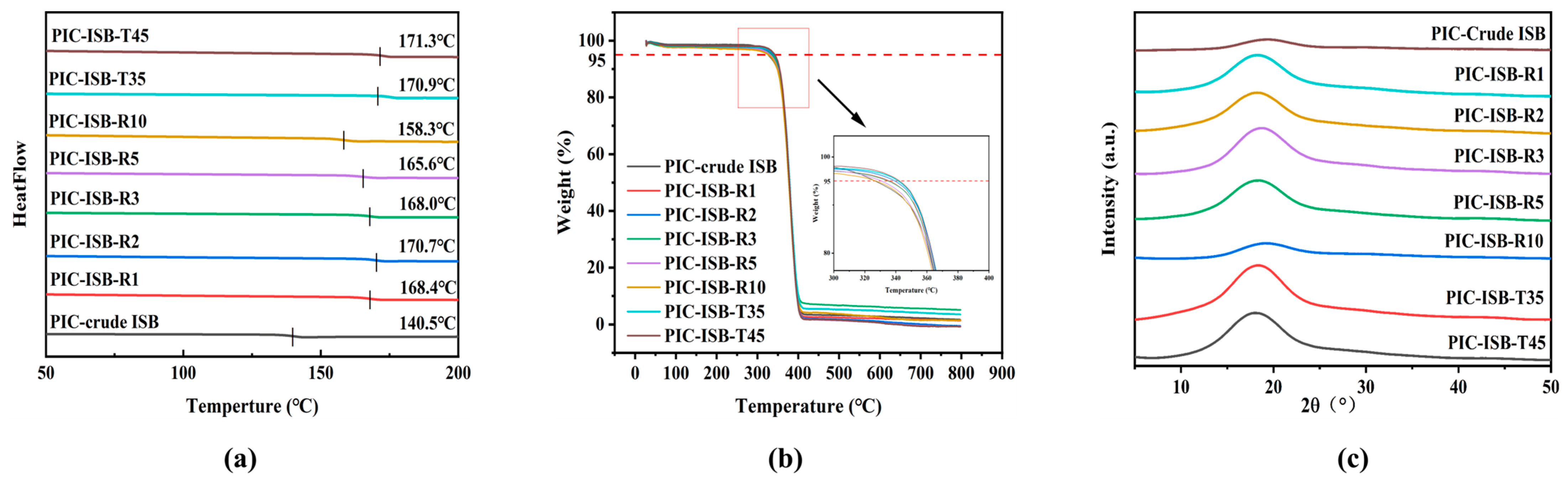

3.5.2. Thermal Properties

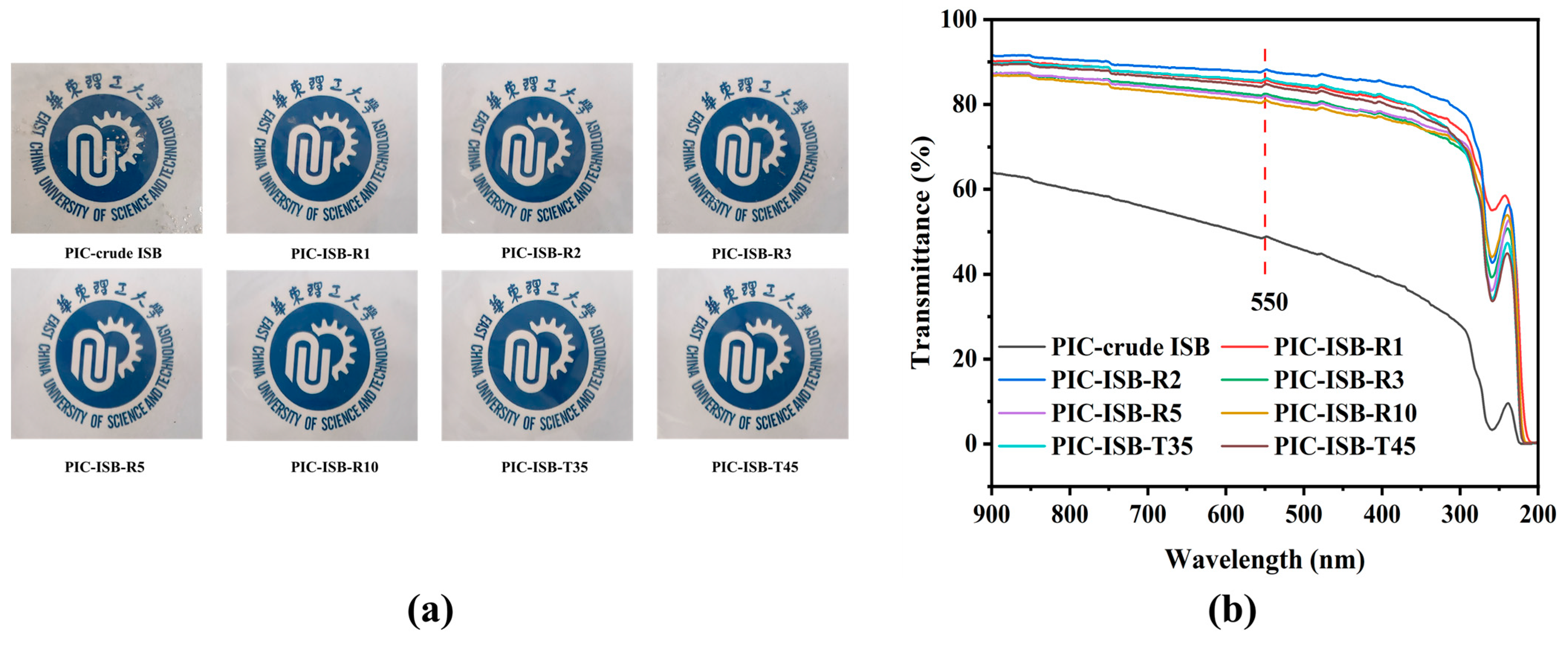

3.5.3. Optical Properties

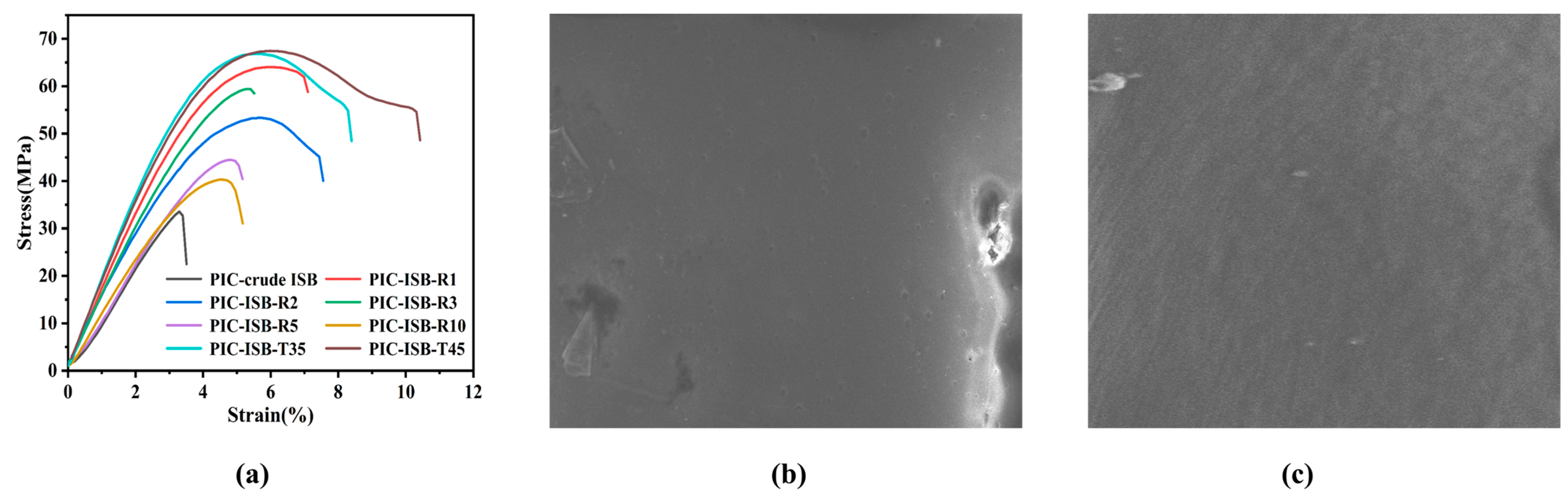

3.5.4. Mechanical Properties

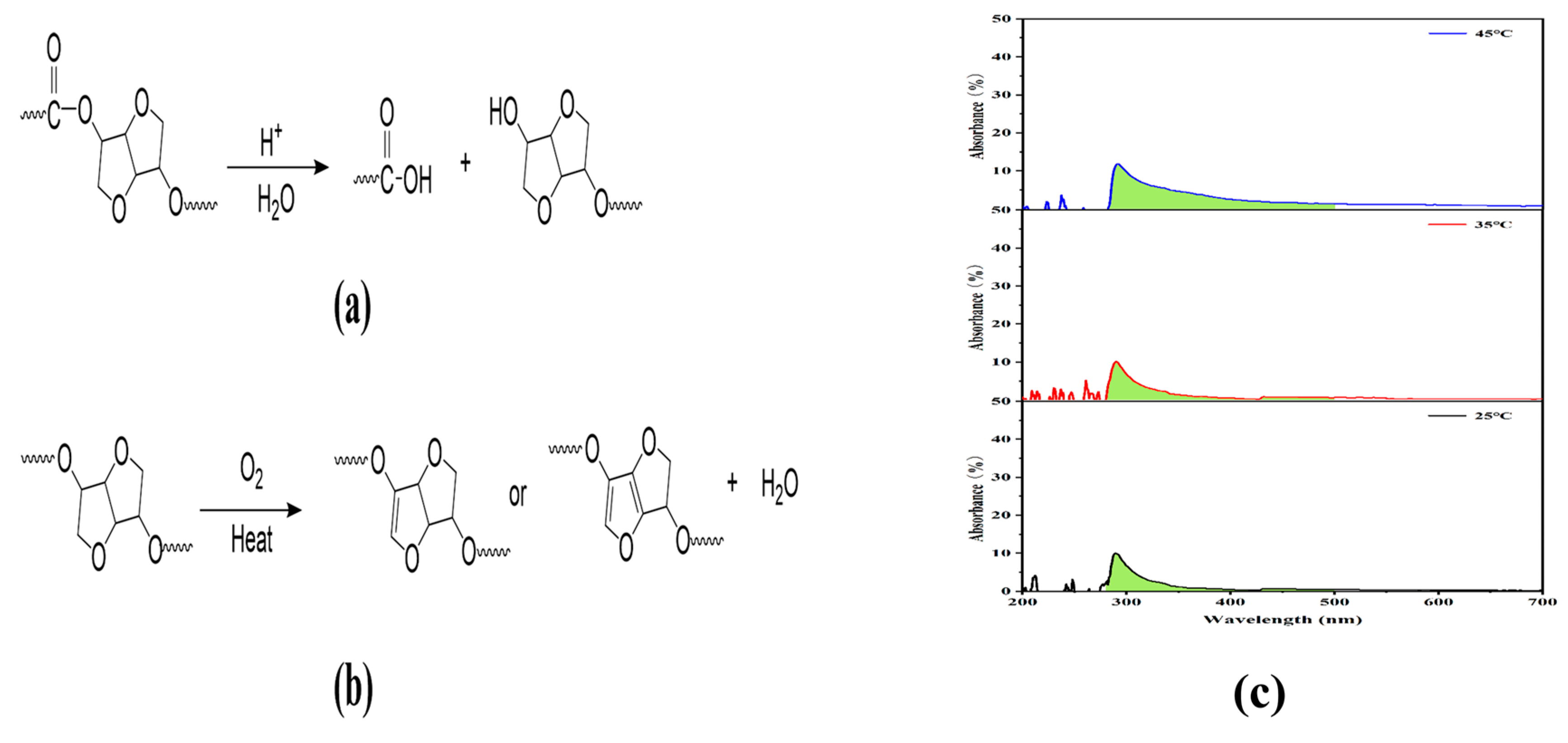

3.5.5. Polymer Backbone Structure and Terminal Groups

3.5.6. Structure of the Transurethanization/Polycondensation Distillates

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soliman, O.R.; Mabied, A.F.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Labeeb, A.M. Nanosilica/recycled polycarbonate composites for electronic packaging. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 329, 130105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotaka, T.; Kondo, F.; Niimi, R.; Togashi, F.; Morita, Y. Industrialization of automotive glazing by polycarbonate and hard-coating. Polym. J. 2019, 51, 1249–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, V.D.; Patil, A.J.; Kandasubramanian, B. Polycarbonate nanocomposites for high impact applications. In Handbook of Consumer Nanoproducts; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Xia, R.; Zhang, Y.; Guan, Z. Enhanced Mechanical and Hydrophobic Antireflective Nanocoatings Fabricated on Polycarbonate Substrates by Combined Treatment of Water and HMDS Vapor. Materials 2023, 16, 3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačič, A.; Gys, C.; Gulin, M.R.; Kosjek, T.; Heath, D.; Covaci, A.; Heath, E. The migration of bisphenols from beverage cans and reusable sports bottles. Food Chem. 2020, 331, 127326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Yan, Y. Molecular dynamics study of the migration of Bisphenol A from polycarbonate into food simulants. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 741, 137125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Alamilla, P.; Castillo-Sanchez, R.; Cortes-Reynosa, P.; Sanchez-Juarez, M.; Gomez, R.; Salazar, E.P. 4T1 breast cancer cells exposed to extracellular vesicles from MDA-MB-231 cells stimulated with bisphenol A increase the growth of mammary tumors and metastasis in female Balb/cJ mice. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2025, 608, 112641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yum, S.; Kim, H.; Seo, Y. Synthesis and characterization of isosorbide based polycarbonates. Polymer 2019, 179, 121685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Xu, W.; Cai, B.; Wang, L.; Luo, Z.; Wang, B. A DOPO-Based Compound Containing Aminophenyl Silicone Oil for Reducing Fire Hazards of Polycarbonate. Materials 2023, 16, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.B.; Lim, S.; Lee, Y.; Park, C.H.; Lee, H.J. Green Chemistry for Crosslinking Biopolymers: Recent Advances in Riboflavin-Mediated Photochemistry. Materials 2023, 16, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, M.; Palkovits, R. Isosorbide as a renewable platform chemical for versatile applications—Quo vadis? ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Pu, Z.; Hou, H.; Li, X.; Zhu, R.; Wang, X.; Yu, D.; Zhong, J. Comparison of the properties of bioderived polycarbonate and traditional bisphenol-A polycarbonate. J. Polym. Res. 2023, 30, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aricò, F.; Tundo, P. Isosorbide and dimethyl carbonate: A green match. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 2256–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; He, H.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, F. Design and synthesis of gradient-refractive index isosorbide-based polycarbonates for optical uses. React. Funct. Polym. 2022, 170, 105145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, M.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, S. Bio-based polycarbonates: Progress and prospects. RSC Sustain. 2023, 1, 2162–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-de-Miranda-Jiménez-de-Aberasturi, O.; Centeno-Pedrazo, A.; Prieto Fernández, S.; Rodriguez Alonso, R.; Medel, S.; María Cuevas, J.; Monsegue, L.G.; De Wildeman, S.; Benedetti, E.; Klein, D. The future of isosorbide as a fundamental constituent for polycarbonates and polyurethanes. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2021, 14, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, L.; An, H.; Li, C.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, W.; Xu, F.; Zhang, S. Cost-effective synthesis of high molecular weight biobased polycarbonate via melt polymerization of isosorbide and dimethyl carbonate. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 9968–9979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-A.; Choi, J.; Ju, S.; Jegal, J.; Lee, K.M.; Hwang, S.Y.; Oh, D.X.; Park, J. Copolycarbonates of bio-based rigid isosorbide and flexible 1, 4-cyclohexanedimethanol: Merits over bisphenol-A based polycarbonates. Polymer 2017, 116, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.; Kim, S.; Im, S. Structural deformation phenomenon of synthesized poly (isosorbide-1, 4-cyclohexanedicarboxylate) in hot water. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 6315–6322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, W.; Niu, D.; He, H.; Xu, F. Efficient synthesis of isosorbide-based polycarbonate with scalable dicationic ionic liquid catalysts by balancing the reactivity of the endo-OH and exo-OH. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, F.; He, H.; Ding, W.; Fang, W.; Sun, W.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S. Synthesis of high-molecular weight isosorbide-based polycarbonates through efficient activation of endo-hydroxyl groups by an ionic liquid. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 3891–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lai, W.; Su, L.; Wu, G. Effect of catalyst on the molecular structure and thermal properties of isosorbide polycarbonates. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 4824–4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbecq, F.; Khodadadi, M.R.; Padron, D.R.; Varma, R.; Len, C. Isosorbide: Recent advances in catalytic production. Mol. Catal. 2020, 482, 110648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Yang, J.; Guo, J.; Wang, S.; Yuan, D.; Zhao, N.; Xiao, F.; Gao, J. Preparation of isosorbide by dehydration of sorbitol on hierarchical Beta zeolites under solvent-free conditions. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2024, 368, 113009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, J.; Chen, Q.; Wu, J.; Wang, H. Influence of polyol impurities on the transesterification kinetics, molecular structures and properties of isosorbide polycarbonate. Polym. Chem. 2024, 15, 4204–4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribot, A.; Amer, G.; Alio, M.A.; de Baynast, H.; Delattre, C.; Pons, A.; Mathias, J.-D.; Callois, J.-M.; Vial, C.; Michaud, P. Wood-lignin: Supply, extraction processes and use as bio-based material. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 112, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eo, Y.S.; Rhee, H.-W.; Shin, S. Catalyst screening for the melt polymerization of isosorbide-based polycarbonate. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2016, 37, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyung, D.H.; Jung, Y.J.; Kim, J.K.; Ryu, H. Method for Preparing High Purity Anhydrosugar Alcohols by Thin Film Distillation. U.S. Pantent, US9290508B2, 22 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, M.A.; Wohlers, M.; Witteler, H.B.; Zey, E.G.; Kvakovszky, G.; Shockley, T.H.; Charbonneau, L.F.; Kohle, N.; Rieth, J. Process and Products of Purification of Anhydrosugar Alcohols. European Patent, EP1140733B1, 27 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandratos, S.D. Ion-exchange resins: A retrospective from industrial and engineering chemistry research. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaragal, R.; Mutnuri, S. Nitrates removal using ion exchange resin: Batch, continuous column and pilot-scale studies. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 739–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, H.; Nishihama, S.; Yoshizuka, K. Separation and recovery of gold from waste LED using ion exchange method. Hydrometallurgy 2015, 157, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachinski, A.M. Environmental Ion Exchange: Principles and Design; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Sadia, M.; Azeem, M.; Ahmad, M.Z.; Umar, M.; Abbas, Z.U. Ion exchange resins and their applications in water treatment and pollutants removal from environment: A review: Ion exchange resins and their applications. Futur. Biotechnol. 2023, 3, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mancilha, I.M.; Karim, M.N. Evaluation of ion exchange resins for removal of inhibitory compounds from corn stover hydrolyzate for xylitol fermentation. Biotechnol. Prog. 2003, 19, 1837–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlichting, H.; Gersten, K. Boundary-Layer Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Liu, L.; He, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, D. Study on the Process and Mechanism of Removing Chloride Ions from Desulfurization Ionic Liquid by Modified Ion Exchange Resin. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 21835–21845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.A.; Abad, K.; Kharel, P.; Omosebi, A.; Thompson, J. Downstream separation of formic acid with anion-exchange resin from electrocatalytic carbon dioxide (CO2) conversion: Adsorption, kinetics, and equilibrium modeling. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 2779–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Qin, J.; Fang, K.; Zhang, G.; Cao, Z.; Li, Q.; Wang, M.; Guan, W.; Wu, S.; Wu, X. Efficient lithium recovery from spent LiFePO4 cathodes via alkaline pressure leaching. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 378, 134700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H.; Ree, M.; Kim, H. Acid-and base-catalyzed hydrolyses of aliphatic polycarbonates and polyesters. Catal. Today 2006, 115, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, R.; Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Guo, M.; Yang, F.; Wu, J.; Wang, H. Strong, Tough, and Heat-Resistant Isohexide-Based Copolycarbonates: An Ecologically Safe Alternative for Bisphenol-A Polycarbonate. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 7553–7565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Ren, J.; Shen, W.; Zhang, S.; Ji, P.; Wang, C.; Wang, H. Synthesis of thermal-resistant polyester-polycarbonate with fully rigid structure from biobased isosorbide. Macromolecules 2024, 57, 6284–6294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Wu, G. Thermo-induced chain scission and oxidation of isosorbide-based polycarbonates: Degradation mechanism and stabilization strategies. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2022, 202, 110028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Zhong, J.; Pu, Z.; Hou, H.; Li, X.; Zhu, R.; Wang, X.; Wu, F.; Zheng, P.; Liu, J. Synthesis and properties of biobased polycarbonate based on isosorbitol. J. Polym. Res. 2023, 30, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Dong, X.; Liu, H. Analysis of the distillate in the polycarbonate manufacturing process by high performance liquid chromatography. World Chem. 1999, 7, 43–44. [Google Scholar]

| Impurities | Pseudo-First-Order Model | Pseudo-Second-Order Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qe (mg/g) | k1 (min−1) | R2 | qe (mg/g) | k2 (g/mg/min) | R2 | |

| Formic Acid | 5.92 | 0.112 | 0.983 | 6.42 | 0.316 | 0.992 |

| Impurities | Film Diffusion | Particle Diffusion | Chemical Reaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | k1 (min−1) | R2 | k2 (min−1) | R2 | k3 (min−1) | |

| Formic Acid | 0.926 | 0.006 | 0.828 | 0.008 | 0.890 | 0.006 |

| ISB Sample a | pH of ISB | Content of Formic Acid (mg/L) | Mn (kg/mol) | Mw (kg/mol) | PDI | Terminal Groups b | Carbonyl Structures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| endo-OH | exo-OH | -OPh | a1 | a3 | a1/a3 | ||||||

| crude ISB | 2.75 | 1.40 | 10.1 | 17.9 | 1.77 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.53 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.95 |

| ISB-R1 | 7.48 | 0.41 | 48.9 | 80.2 | 1.64 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 1.04 |

| ISB-R2 | 7.57 | 0.38 | 52.5 | 84.0 | 1.60 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 1.04 |

| ISB-R3 | 7.22 | 0.49 | 41.6 | 69.5 | 1.67 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.37 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 1.02 |

| ISB-R5 | 6.70 | 0.62 | 35.2 | 58.8 | 1.67 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 1.00 |

| ISB-R10 | 5.53 | 0.83 | 27.3 | 46.9 | 1.72 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.96 |

| ISB-T35 | 7.64 | 0.34 | 53.7 | 84.8 | 1.58 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 1.06 |

| ISB-T45 | 7.68 | 0.34 | 53.9 | 85.2 | 1.58 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 1.06 |

| ISB Sample | pH of ISB | Content of Formic Acid (mg/L) | Tg (°C) | Td-5% (°C) | 550 nm Transmittance (%) | Elongation at Break (%) | Young’s Modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| crude ISB | 2.75 | 1.40 | 140.5 | 326.9 | 48.7 | 3.5 | 1.11 |

| ISB-R1 | 7.48 | 0.41 | 168.4 | 336.9 | 85.5 | 7.1 | 1.70 |

| ISB-R2 | 7.57 | 0.38 | 170.7 | 340.1 | 88.1 | 7.6 | 1.76 |

| ISB-R3 | 7.22 | 0.49 | 168.0 | 334.4 | 82.5 | 5.7 | 1.54 |

| ISB-R5 | 6.70 | 0.62 | 165.6 | 330.1 | 82.0 | 5.3 | 1.43 |

| ISB-R10 | 5.53 | 0.83 | 158.3 | 327.3 | 80.9 | 5.2 | 1.16 |

| ISB-T35 | 7.64 | 0.34 | 170.9 | 341.5 | 86.0 | 8.4 | 1.79 |

| ISB-T45 | 7.68 | 0.34 | 171.3 | 341.7 | 84.7 | 10.2 | 1.84 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Han, F.; Zhang, Y. Purification of Isosorbide via Ion Exchange Resin for High-Performance Bio-Based Polycarbonate. Materials 2026, 19, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010030

Han F, Zhang Y. Purification of Isosorbide via Ion Exchange Resin for High-Performance Bio-Based Polycarbonate. Materials. 2026; 19(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Fei, and Yan Zhang. 2026. "Purification of Isosorbide via Ion Exchange Resin for High-Performance Bio-Based Polycarbonate" Materials 19, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010030

APA StyleHan, F., & Zhang, Y. (2026). Purification of Isosorbide via Ion Exchange Resin for High-Performance Bio-Based Polycarbonate. Materials, 19(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010030