Characterization of Ti/Cu Dissimilar Metal Butt-Welded by the Cold Welding Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

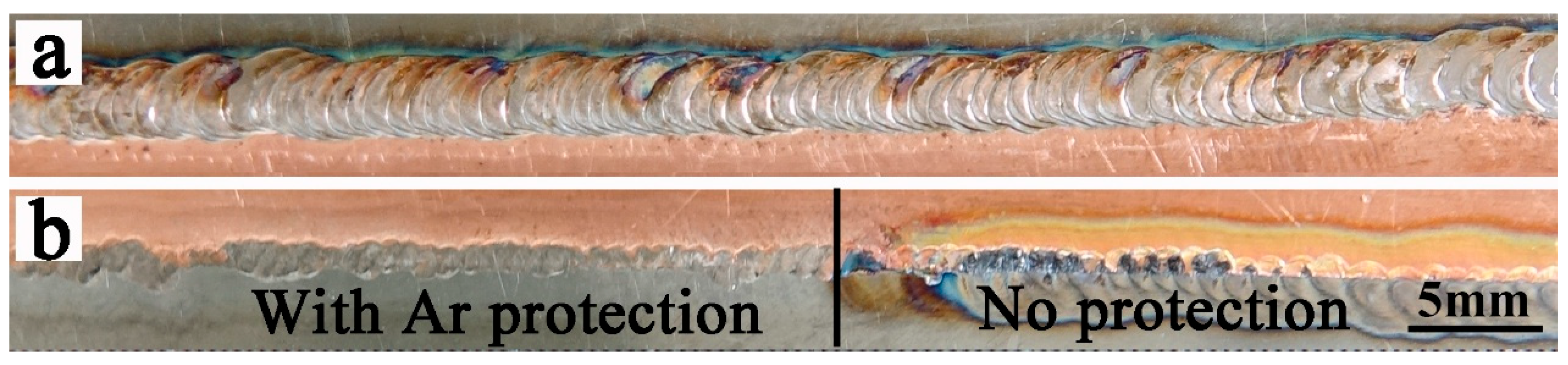

3.1. Analysis of Surface Morphology and Microstructure of Welded Joints

3.2. Mechanical Properties and Fracture Analysis of Joints

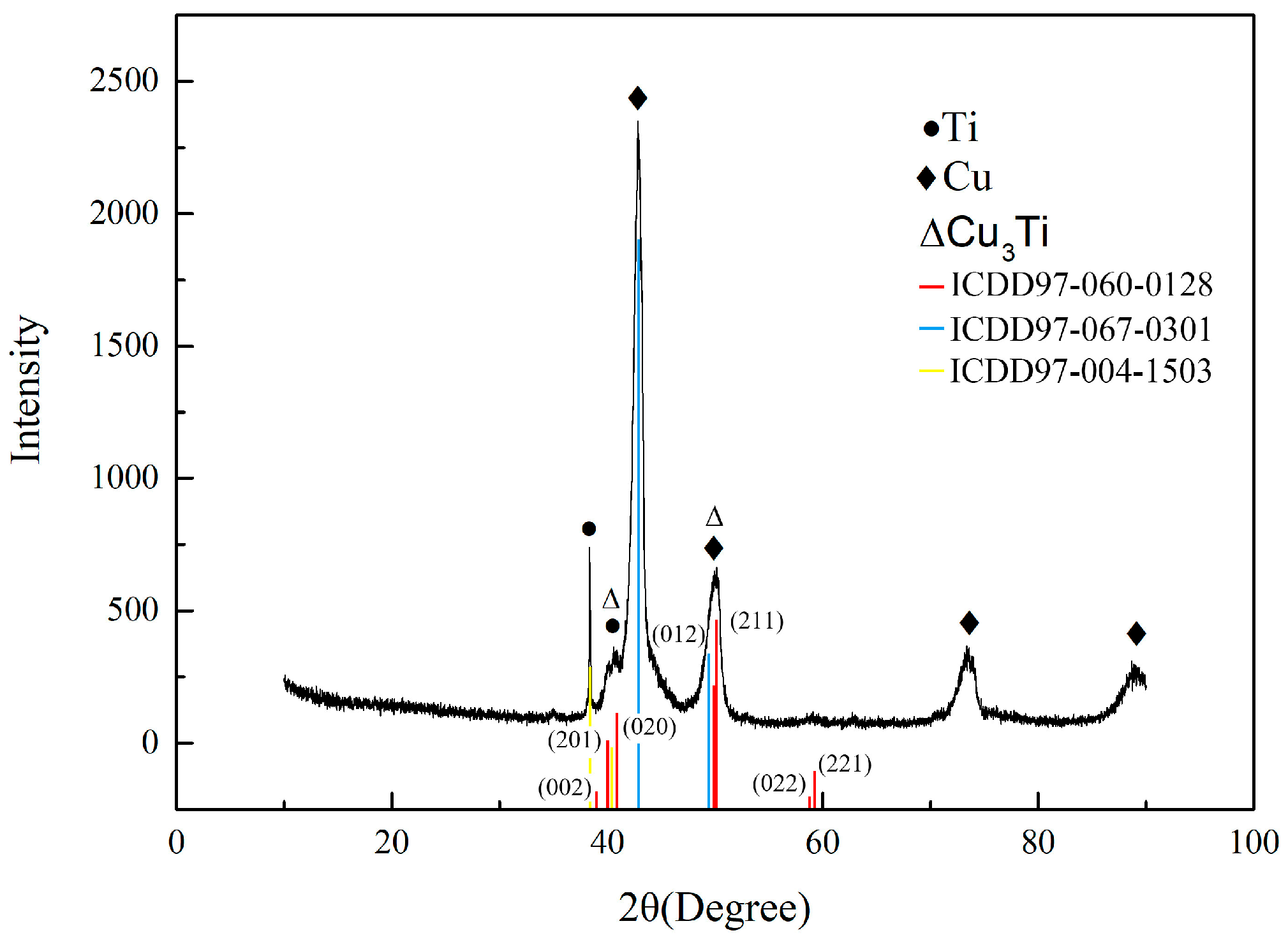

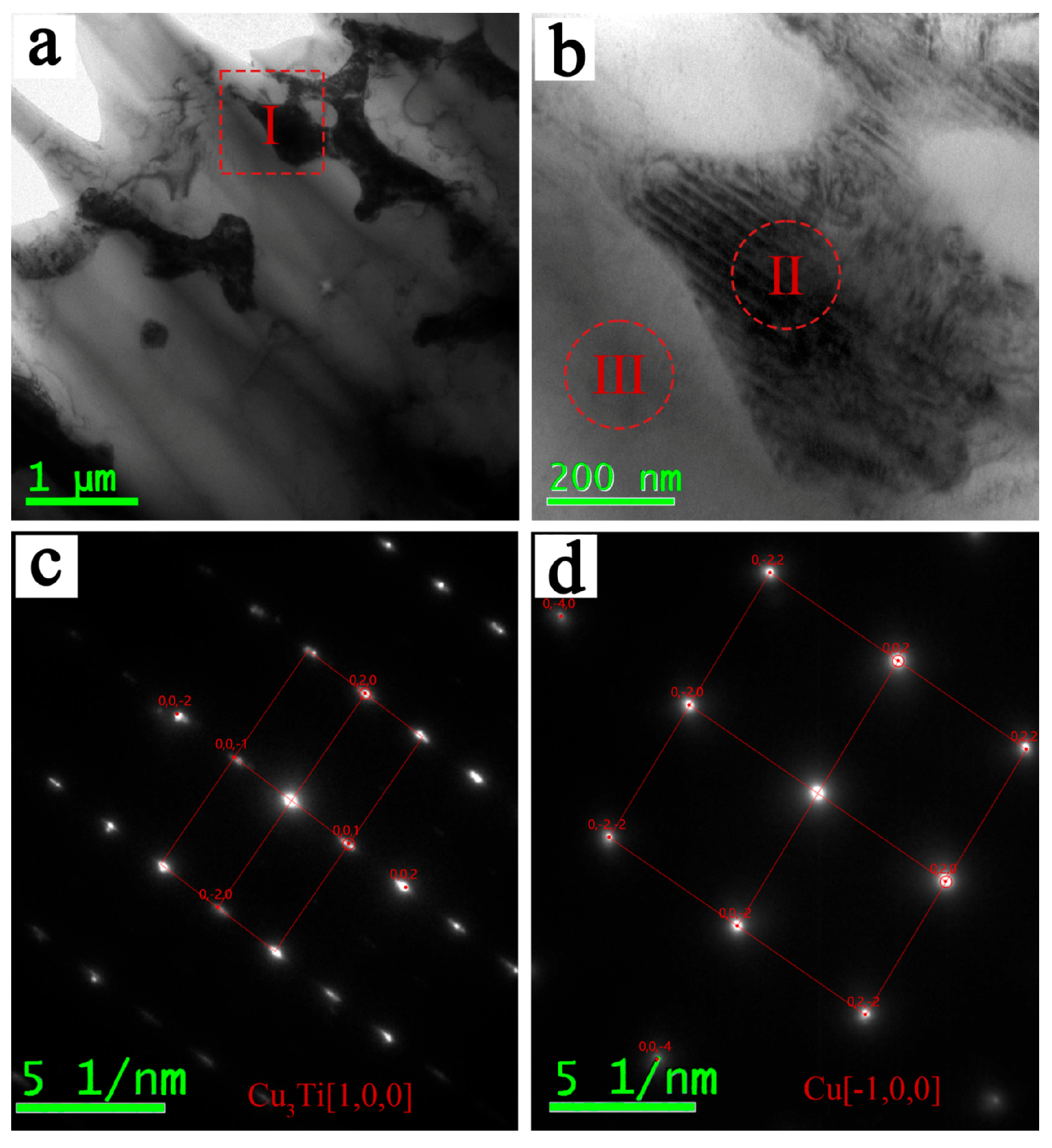

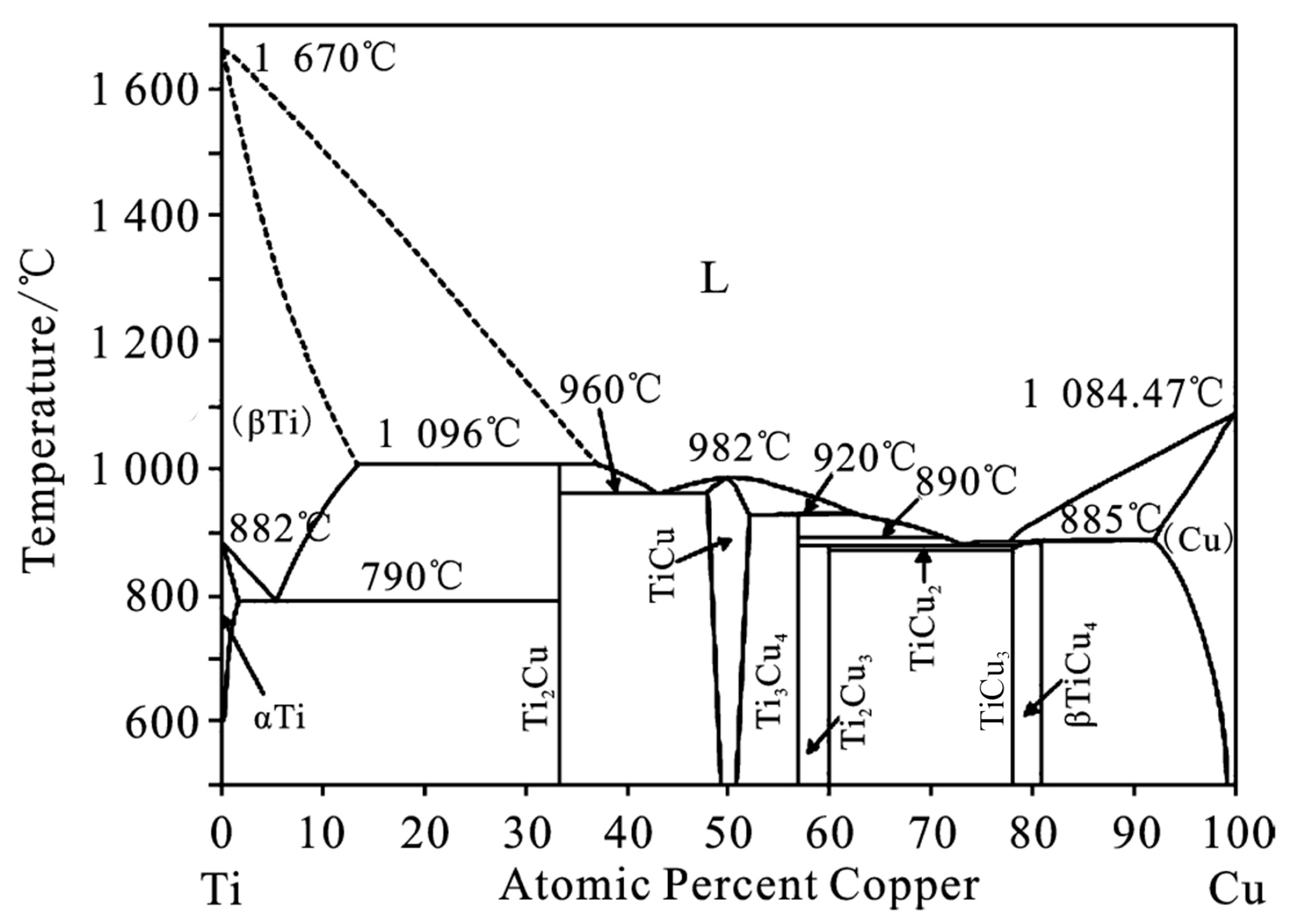

3.3. Formation Mechanism of Cu3Ti in the Weld

3.4. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| EPMA | Electron Probe Micro-Analyzer |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| FZ | Fusion Zone |

| IMC | Intermetallic Compound |

| HAZ | Heat-Affected Zone |

References

- Banerjee, D.; Williams, J.C. Perspectives on titanium science and technology. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 844–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Tan, C.; You, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; Nie, Z.; Yu, X.; Zhao, X. Effect of α phase on high-strain rate deformation behavior of laser melting deposited Ti-6.5Al-1Mo-1V-2Zr titanium alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A Struct. Mater. 2019, 750, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, A.; Suwas, S.; Kailas, S.V. Significance of tool offset and copper interlayer during friction stir welding of aluminum to titanium. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 100, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, W.; Song, X.; Huang, Y. Influence of dwell time on microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of dissimilar friction stir spot welded aluminum–copper metals. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 2613–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladkovsky, S.V.; Kuteneva, S.V.; Sergeev, S.N. Microstructure and mechanical properties of sandwich copper/steel composites produced by explosive welding. Mater. Charact. 2019, 154, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Feng, Z.; Chen, J. Microstructures and properties of titanium–copper lap welded joints by cold metal transfer technology. Mater. Des. 2014, 53, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, H.; Chulist, R.; Miszczyk, M.; Lityńska-Dobrzyńska, L.; Cios, G.; Gałka, A.; Petrzak, P.; Szlezynger, M. Towards a better understanding of the phase transformations in explosively welded copper to titanium sheets. Mater. Sci. Eng. A Struct. Mater. 2020, 784, 139285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhou, Q.; Peng, Y.; Xu, X.; Diao, C.; Kong, J.; Luo, T.; Wang, K.; Zhu, J. Study on strengthening mechanism of Ti/Cu electron beam welding. Mater. Des. 2017, 121, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, P.; Shi, H.; Wang, L. Influence of filler metal on microstructure and properties of titanium/copper weld joint by GTAW weldments. Mater. Sci. Eng. A Struct. Mater. 2022, 833, 142508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Wang, T.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Feng, J. Effect of Cu66V34 filler thickness on the microstructure and properties of titanium/copper joint by electron beam welding. J. Mater. Process Technol. 2019, 267, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zhang, B.; Liu, W.; Feng, J.-C. Influence of electron-beam superposition welding on intermetallic layer of Cu/Ti joint. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2012, 22, 2416–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, J.; Yu, H. Laser welding of Ti6Al4V to Cu using a niobium interlayer. J. Mater. Process Technol. 2019, 270, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Panton, B.; Oliveira, J.P.; Han, A.; Zhou, Y.N. Dissimilar laser welding of NiTi shape memory alloy and copper. Smart Mater. Struct. 2015, 24, 125036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M.; Saitoh, Y.; Kusaka, M.; Kaizu, K.; Fuji, A. Effect of friction pressure on joining phenomena of friction welds between pure titanium and pure copper. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2011, 16, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Jung, S.B.; Shur, C.C.; Yeon, Y.-M.; Kim, D.-U. Mechanical properties of copper to titanium joined by friction welding. J. Mater. Sci. 2003, 38, 1281–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, Y.; Chen, P.; Bataev, I.A.; Gao, X. Experimental and numerical investigations of interface properties of Ti6Al4V/CP-Ti/Copper composite plate prepared by explosive welding. Def. Technol. 2021, 17, 1592–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, K.; Kaya, Y.; Kahraman, N. Experimental study of diffusion welding/bonding of titanium to copper. Mater. Des. 2012, 37, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Shen, J.; Hu, S.; Gou, J.; Kannatey-Asibu, E. Wire and arc additive manufactured Ti–6Al–4V/Al–6.25 Cu dissimilar alloys by CMT-welding: Effect of deposition order on reaction layer. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2020, 25, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Dong, H.; Ma, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Wu, B. Interfacial layer regulation and its effect on mechanical properties of Ti6Al4V titanium alloy and T2 copper dissimilar joints by cold metal transfer welding. J. Manuf. Process 2022, 75, 1100–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Xie, S.; Chen, T.; Wang, X.; Yu, X.; Yang, L.; Ni, Z.; Ling, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Shi, J.; et al. Numerical Simulation and Process Optimization of Laser Welding in 6056 Aluminum Alloy T-Joints. Crystals 2025, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Xie, S.; Tian, Y.; Wang, X.; Yu, X.; Chen, N.; Yuan, Z.; Han, P.; Xia, H.; Wang, P.; et al. Numerical simulation and process parameter optimization of laser spot welding for ultra-thin sheets. Opt. Laser Technol. 2026, 193, 114240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E8/E8M-2021; Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, W.; Yan, K.; Liu, C.; Zou, J. Microstructure and properties of Cu/Ti laser welded joints. J. Mater. Process Technol. 2017, 257, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, A.; Kailas, S.V.; Suwas, S. Formation sequence of intermetallics and kinetics of reaction layer growth during solid state reaction between titanium and aluminum. Materialia 2020, 11, 100702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, Y.; Hoshino, K.; Hirano, K.I. Diffusion of titanium in copper. Met. Trans A 1977, 8, 997–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffnit, P.; Stallybrass, C.; Konrad, J.; Stein, F.; Weinberg, M. A Scheil–Gulliver model dedicated to the solidification of steel. Calphad 2015, 48, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data Retrieved from the Materials Project for TiCu3 (mp-12546) from Database Version v2025.09.25. Available online: https://next-gen.materialsproject.org/materials/mp-12546 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Data Retrieved from the Materials Project for TiCu4 (mp-1188441) from Database Version v2025.09.25. Available online: https://next-gen.materialsproject.org/materials/mp-1188441 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

| Serial Number | Percentage Composition (wt. %) | Inference composition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | Ti | Al | Zr | V | ||

| 1 | 99.66 | - | 0.34 | - | - | Cu |

| 2 | 99.06 | - | 0.94 | - | - | Cu |

| 3 | 93.24 | 5.11 | 1.31 | 0.09 | 0.25 | (Cu), Cu3Ti |

| 4 | 92.05 | 6.45 | 1.15 | 0.13 | 0.22 | (Cu), Cu3Ti |

| 5 | 91.50 | 5.93 | 2.03 | 0.08 | 0.46 | (Cu), Cu3Ti |

| 6 | 89.64 | 5.58 | 3.95 | 0.24 | 0.59 | (Cu), Cu3Ti |

| 7 | 80.83 | 15.12 | 2.66 | 0.15 | 1.24 | (Cu), TiCu4 |

| 8 | 0.12 | 89.10 | 5.51 | 0.06 | 5.21 | (Ti), TiAl3 |

| 9 | 0.08 | 91.54 | 6.38 | - | 2.01 | (Ti), TiAl3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xiao, Y.; Liu, F.; Chen, N. Characterization of Ti/Cu Dissimilar Metal Butt-Welded by the Cold Welding Process. Materials 2026, 19, 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010197

Xiao Y, Liu F, Chen N. Characterization of Ti/Cu Dissimilar Metal Butt-Welded by the Cold Welding Process. Materials. 2026; 19(1):197. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010197

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Yunyi, Fei Liu, and Nuo Chen. 2026. "Characterization of Ti/Cu Dissimilar Metal Butt-Welded by the Cold Welding Process" Materials 19, no. 1: 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010197

APA StyleXiao, Y., Liu, F., & Chen, N. (2026). Characterization of Ti/Cu Dissimilar Metal Butt-Welded by the Cold Welding Process. Materials, 19(1), 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010197