Application of Potato Peels as an Unconventional Sorbent for the Removal of Anionic and Cationic Dyes from Aqueous Solutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Potato Peels

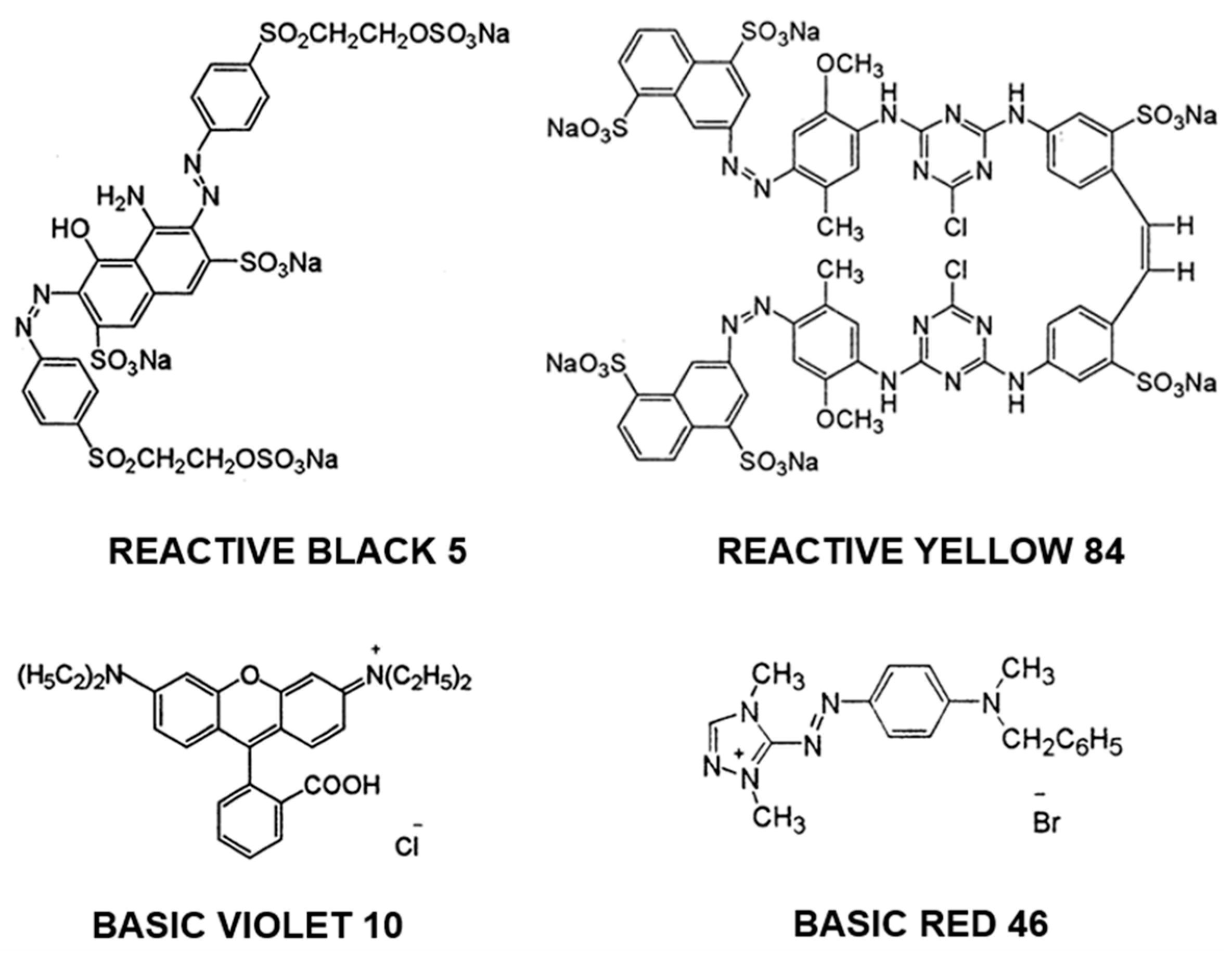

2.2. Dyes

2.3. Chemical Reagents

- NaOH (sodium hydroxide) > 99.9%—(pH correction of dye solutions);

- HCl (hydrochloric acid)—37%—(pH correction of dye solutions)

2.4. Laboratory Equipment

2.5. Sorbent Preparation—Potato Peels (PP)

2.6. FTIR Analysis of the PP

2.7. Impact of Initial Solution pH on the Sorptive Removal of Dyes by PP

2.8. Kinetic Studies of Dye Sorption onto PP

2.9. Determination of the Maximum Sorption Capacity of PP for Dyes

- PP (potato peels) was tested against four dyes: RB5, RY84, BV10, and BR46.

- Dye stock and working solutions were prepared exclusively with high-purity deionized water.

- All batch experiments were conducted thrice (in triplicate) to ensure the statistical reliability of the collected data.

- The PP dosage was kept constant at 10.00 g d.m./L (grams dry matter per liter) in all experiments.

- The research used PP in its fresh, not dried, form.

- The PP portions were accurately weighed (to ±0.001 g) using a precision balance.

- Continuous agitation, provided by either the orbital shaker or the magnetic stirring units, facilitated the complete and consistent suspension of the biomass across the entire reactive volume.

- Dye concentrations were quantified by spectrophotometry using a UV-VIS spectrophotometer with a 10 mm optical path length cuvette.

- Standard curves permitted the determination of RB5, RY84, and BR46 levels within a 50 mg/L limit, whereas BV10 concentrations were measured using a 0–10 mg/L calibration scale. Curves were prepared at λmax (values given in Table 2, Section 2.2). Solutions exceeding the linearity range of the calibration curves were diluted with deionized water before measurement.

- The laboratory air temperature was maintained at a stable 25 °C throughout the analyses.

2.10. Calculations

- QS—amount of dye adsorbed [mg/g]

- C0—initial dye concentration in solution [mg/L]

- CS—dye concentration remaining in solution after sorption [mg/L]

- V—volume of the dye solution utilized [L]

- m—mass of the dry sorbent used [g]

- q—instantaneous amount of dye adsorbed at time [mg/g].

- qe—the amount of dye sorbed at equilibrium [mg/g].

- t—sorption contact time [min].

- k1—the rate constant of the pseudo-first-order kinetic model [1/min].

- k2—the rate constant of the pseudo-second-order kinetic model [g/(mg*min)].

- kid—the intraparticle diffusion rate constant [mg/(g*min0.5)].

- Q—amount of dye adsorbed at equilibrium [mg/g].

- Qmax—maximum monolayer sorption capacity in the Langmuir model [mg/g].

- b1—the theoretical maximum loading of the high-energy (Type I) active centers [mg/g].

- b2—the theoretical maximum loading of the high-energy (Type II) active centers [mg/g].

- KC—Langmuir adsorption constant [L/mg].

- K1, K2—adsorption constants for type I and type II sites in the Langmuir 2 model [L/mg].

- K—Freundlich equilibrium constant (sorption capacity indicator).

- n—Freundlich adsorption intensity indicator.

- C—the equilibrium dye concentration in the aqueous phase [mg/L].

- I—ionic strength of the solution [mol/L].

- ci—molar concentration of the i-th ion [mol/L].

- zi—charge number of the i-th ion.

- ∑—summation over all ions in the solution.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of the PP

3.1.1. FTIR Analysis

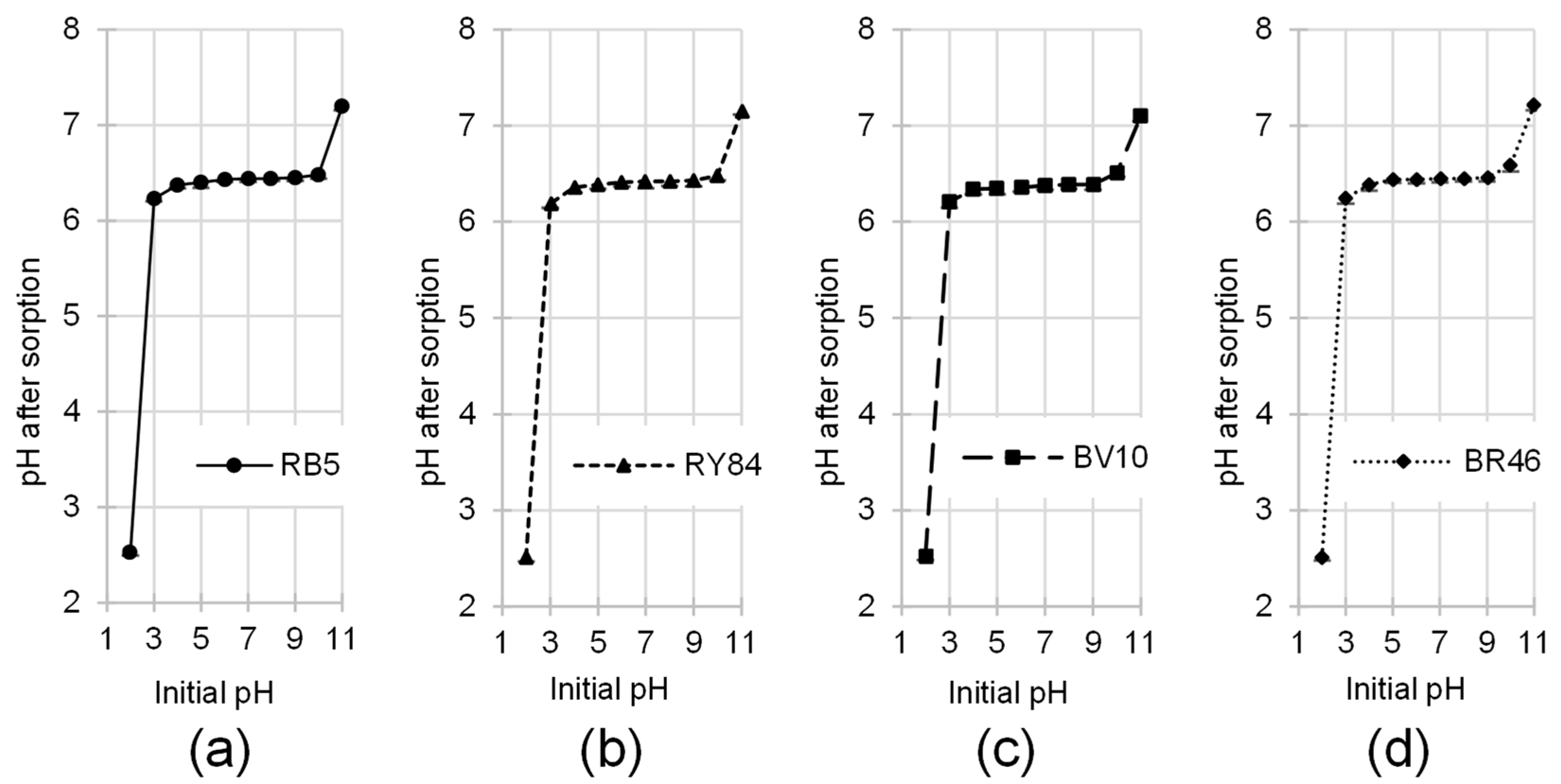

3.1.2. Determination of the Sorbent pHPZC

3.2. Effect of pH on Dye Sorption by PP

3.3. Kinetics of Dyes Sorption onto PP

3.4. Maximum Sorption Capacity of PP

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Synthetic Dyes and Pigments Market Size, Share & Report [2033]. Available online: https://www.marketreportsworld.com/market-reports/synthetic-dyes-and-pigments-market-14715350 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Slama, H.B.; Bouket, A.C.; Pourhassan, Z.; Alenezi, F.N.; Silini, A.; Cherif-Silini, H.; Oszako, T.; Luptakova, L.; Golińska, P.; Belbahri, L. Diversity of Synthetic Dyes from Textile Industries, Discharge Impacts and Treatment Methods. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Rani, R.M.; Patle, D.S.; Kumar, S. Emerging Bioremediation Technologies for the Treatment of Textile Wastewater Containing Synthetic Dyes: A Comprehensive Review. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2022, 97, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Ye, W.; Xie, M.; Seo, D.H.; Luo, J.; Wan, Y.; Van der Bruggen, B. Environmental Impacts and Remediation of Dye-Containing Wastewater. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 785–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Adhikary, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Roy, D.; Chatterjee, S.; Chakraborty, A.; Banerjee, D.; Ganguly, A.; Nanda, S.; Rajak, P. Contamination of Textile Dyes in Aquatic Environment: Adverse Impacts on Aquatic Ecosystem and Human Health, and Its Management Using Bioremediation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsukaibi, A.K.D. Various Approaches for the Detoxification of Toxic Dyes in Wastewater. Processes 2022, 10, 1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, D.; Rana, I.; Mishra, V.; Ranjan, K.R.; Singh, P. Unveiling the Impact of Dyes on Aquatic Ecosystems through Zebrafish–A Comprehensive Review. Environ. Res. 2024, 261, 119684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Cherwoo, L.; Singh, R. Decoding Dye Degradation: Microbial Remediation of Textile Industry Effluents. Biotechnol. Notes 2023, 4, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragaw, T.A. A Review of Dye Biodegradation in Textile Wastewater, Challenges Due to Wastewater Characteristics, and the Potential of Alkaliphiles. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 16, 100493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuyucu, A.E.; Selçuk, A.; Önal, Y.; Alacabey, İ.; Erol, K. Effective Removal of Dyes from Aqueous Systems by Waste-Derived Carbon Adsorbent: Physicochemical Characterization and Adsorption Studies. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, J.; Wu, Y.; Jin, L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Z. Study on the Adsorption Properties of Multiple-Generation Hyperbranched Collagen Fibers towards Isolan-Series Acid Dyes. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 6855–6868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenkie, K.M.; Wu, W.Z.; Clark, R.L.; Pfleger, B.F.; Root, T.W.; Maravelias, C.T. A Roadmap for the Synthesis of Separation Networks for the Recovery of Bio-Based Chemicals: Matching Biological and Process Feasibility. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 1362–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Wang, B.; Wang, R.; Kozhevnikov, I.V. New Adsorption Materials for Deep Desulfurization of Fuel Oil. Materials 2024, 17, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-González, A.M.; Caldera-Villalobos, M.; Peláez-Cid, A.A. Adsorption of Textile Dyes Using an Activated Carbon and Crosslinked Polyvinyl Phosphonic Acid Composite. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 234, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, W.; Zhang, A.; Mian, M.M.; Zhang, Q.; Xiao, L.; Xiao, J.; Ou, T.; Deng, S. Moderate-Temperature Alkaline-Assisted Hydrothermal Regeneration of Spent Activated Carbon after Treating Agrochemical and Pharmaceutical Wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutkoski, J.P.; Schneider, E.E.; Michels, C. How Effective Is Biological Activated Carbon in Removing Micropollutants? A Comprehensive Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, J.A.; Ahmad Zaini, M.A.; Surajudeen, A.; Aliyu, E.N.U.; Omeiza, A.U. Surface Modification of Low-Cost Bentonite Adsorbents—A Review. Part. Sci. Technol. 2019, 37, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhemkhem, A.; Pizarro, A.H.; Molina, C.B. Enhancement of the Adsorption Properties of Two Natural Bentonites by Ion Exchange: Equilibrium, Kinetics and Thermodynamic Study. Clay Miner. 2020, 55, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.S.; Abdul Razak, A.A.; Muslim, M.A. The Use of Inexpensive Sorbents to Remove Dyes from Wastewater-A Review. Eng. Technol. J. 2022, 40, 498–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.N.M.A.; Sultana, N.; Sayem, A.S.M.; Smriti, S.A. Sustainable Adsorbents from Plant-Derived Agricultural Wastes for Anionic Dye Removal: A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caovilla, M.; Oro, C.E.D.; Mores, R.; Venquiaruto, L.D.; Mignoni, M.L.; Di Luccio, M.; Treichel, H.; Dallago, R.M.; Tres, M.V. Exploring Chicken Feathers as a Cost-Effective Adsorbent for Aqueous Dye Removal. Separations 2025, 12, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, M.A.; Ahammad, F.; Chandra Das, B.; Enan, E.T.; Maoya, M.; Khan, M.J.H.; Miem, M.M. Dye Adsorption on Fish Scale Biosorbent from Tannery Wastewater. Next Sustain. 2025, 6, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, M.E.A.; de Sousa, K.S.M.G.; Clericuzi, G.Z.; Ferreira, A.L.d.O.; Soares, M.C.d.S.; Neto, J.C.d.Q. Adsorption of Reactive Dye onto Uçá Crab Shell (Ucides cordatus): Scale-Up and Comparative Studies. Energies 2021, 14, 5876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Dutta, R.K. Adsorptive Removal of Toxic Dyes Using Chitosan and Its Composites; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 223–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Assis Filho, R.B.; Baptisttella, A.M.S.; de Araujo, C.M.B.; Fraga, T.J.M.; de Paiva, T.M.N.; de Abreu, C.A.M.; da Motta Sobrinho, M.A. Removal of Textile Dyes by Benefited Marine Shells Wastes: From Circular Economy to Multi-Phenomenological Modeling. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 296, 113222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murcia-Salvador, A.; Pellicer, J.A.; Rodríguez-López, M.I.; Gómez-López, V.M.; Núñez-Delicado, E.; Gabaldón, J.A. Egg By-Products as a Tool to Remove Direct Blue 78 Dye from Wastewater: Kinetic, Equilibrium Modeling, Thermodynamics and Desorption Properties. Materials 2020, 13, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Leo, C.P.; Show, P.L. Recent Advances in the Synthesis and Applications of PH-Responsive CaCO3. Biochem. Eng. J. 2022, 187, 108446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipkowska, U.; Jόźwiak, T.; Szymczyk, P.; Kuczajowska-Zadrożna, M. The Use of Active Carbon Immobilised on Chitosan Beads for RB5 and BV10 Dye Removal from Aqueous Solutions. Prog. Chem. Appl. Chitin. Deriv. 2017, 22, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, N.; Shefa, N.R.; Reza, K.; Shawon, S.M.A.Z.; Rahman, M.W. Adsorption of Crystal Violet Dye from Synthetic Wastewater by Ball-Milled Royal Palm Leaf Sheath. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quansah, J.O.; Hlaing, T.; Lyonga, F.N.; Kyi, P.P.; Hong, S.H.; Lee, C.G.; Park, S.J. Nascent Rice Husk as an Adsorbent for Removing Cationic Dyes from Textile Wastewater. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkliarenko, Y.; Halysh, V.; Nesterenko, A. Adsorptive Performance of Walnut Shells Modified with Urea and Surfactant for Cationic Dye Removal. Water 2023, 15, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolkou, A.K.; Tsoutsa, E.K.; Kyzas, G.Z.; Katsoyiannis, I.A. Sustainable Use of Low-Cost Adsorbents Prepared from Waste Fruit Peels for the Removal of Selected Reactive and Basic Dyes Found in Wastewaters. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2024, 31, 14662–14689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwiak, T.; Filipkowska, U. Aminated Rapeseed Husks (Brassica napus) as an Effective Sorbent for Removing Anionic Dyes from Aqueous Solutions. Molecules 2024, 29, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Górska-Warsewicz, H.; Rejman, K.; Kaczorowska, J.; Laskowski, W. Vegetables, Potatoes and Their Products as Sources of Energy and Nutrients to the Average Diet in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Potato Production: Insights and Trends from the Latest FAOSTAT Data–Potato News Today. Available online: https://www.potatonewstoday.com/2025/01/09/global-potato-production-in-2023-insights-and-trends-from-faostat-data/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Vescovo, D.; Manetti, C.; Ruggieri, R.; Spizzirri, U.G.; Aiello, F.; Martuscelli, M.; Restuccia, D. The Valorization of Potato Peels as a Functional Ingredient in the Food Industry: A Comprehensive Review. Foods 2025, 14, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mickiewicz, B.; Volkova, E.; Jurczak, R. The Global Market for Potato and Potato Products in the Current and Forecast Period. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2022, 25, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailemariam, T.T.; Madugula, D.R.; Babu, P.J. Production and Characterization of Bio Fertilizer from Potato Peel. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2024, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Bascones, M.; Díez-Gutiérrez, M.A.; Hernández-Navarro, S.; Corrêa-Guimarães, A.; Navas-Gracia, L.M.; Martín-Gil, J. Use of Potato Peelings in Composting Techniques: A High-Priority and Low-Cost Alternative for Environmental Remediation; Global Science Books: Isleworth, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Matin, H.H.A.; Damarjati, B.Y.; Shidqi, M.I.G.; Budiyono, B.; Othman, N.H.; Wahyono, Y. Biogas Production from the Potato Peel Waste: Study of the Effect of C/N Ratio, EM-4 Bacteria Addition and Initial PH. Rev. Gest. Soc. Ambient. 2024, 18, e05421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arapoglou, D.; Varzakas, T.; Vlyssides, A.; Israilides, C. Ethanol Production from Potato Peel Waste (PPW). Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 1898–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awogbemi, O.; Von Kallon, D.V.; Owoputi, A.O. Biofuel Generation from Potato Peel Waste: Current State and Prospects. Recycling 2022, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, S.K.; Sharma, B.; Sharma, A.; Thakur, B.; Soni, R.; Soni, S.K.; Sharma, B.; Sharma, A.; Thakur, B.; Soni, R. Exploring the Potential of Potato Peels for Bioethanol Production through Various Pretreatment Strategies and an In-House-Produced Multi-Enzyme System. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, M.K.; Tiwari, R.K.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, D.; Jaiswal, A.; Changan, S.S.; Dutt, S.; Popović-Djordjević, J.; Singh, B.; et al. Methodological Breakdown of Potato Peel’s Influence on Starch Digestibility, In Vitro Glycemic Response and Pasting Properties of Potato. Am. J. Potato Res. 2024, 101, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Yin, J.Y.; Nie, S.P.; Xie, M.Y. Applications of Infrared Spectroscopy in Polysaccharide Structural Analysis: Progress, Challenge and Perspective. Food Chem. X 2021, 12, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadul, T.Y.S.; Flórez, J.A.F.; Velásquez, H.J.C.; Mendoza, J.G.S.; Ruydiaz, J.E.H. Hydrothermal and Biocatalytic Processes on Native Cassava Flours: Behavior of the Physicochemical, Morphological and Pasting Properties. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2024, 27, e2024014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Copeland, L. Changes of Multi-Scale Structure during Mimicked DSC Heating Reveal the Nature of Starch Gelatinization. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiozon, R.N.; Bonto, A.P.; Padua, J.A.H.; Elbo, E.G.A.; Sampang, J.R.; Kamkajon, K.; Camacho, D.H.; Thumanu, K. Investigating the Effect of Ultrasonication on the Molecular Structure of Potato Starch Using Synchrotron-Based Infrared Spectroscopy. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2022, 12, 6686–6698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saimaiti, M.; Gençcelep, H. Thermal and Molecular Characteristics of Novel Water-Soluble Polysaccharide from the Pteridium Aquilinum and Dryopteris Filix-Mas. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 3, 100401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md Salim, R.; Asik, J.; Sarjadi, M.S. Chemical Functional Groups of Extractives, Cellulose and Lignin Extracted from Native Leucaena Leucocephala Bark. Wood Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukprasert, J.; Thumanu, K.; Phung-On, I.; Jirarungsatean, C.; Erickson, L.E.; Tuitemwong, P.; Tuitemwong, K. Synchrotron FTIR Light Reveals Signal Changes of Biofunctionalized Magnetic Nanoparticle Attachment on Salmonella sp. J. Nanomater. 2020, 2020, 6149713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasylieva, A.; Doroshenko, I.; Vaskivskyi, Y.; Chernolevska, Y.; Pogorelov, V. FTIR Study of Condensed Water Structure. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1167, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multescu, M.; Marinas, I.C.; Susman, I.E.; Belc, N. Byproducts (Flour, Meals, and Groats) from the Vegetable Oil Industry as a Potential Source of Antioxidants. Foods 2022, 11, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivakumar, S.; Prasad Khatiwada, C.; Sivasubramanian, J.; Jini, P.; Prabu, N.; Venkateson, A.; Soundararajan, P. FT-IR Study of Green Tea Leaves and Their Diseases of Arunachal Pradesh, North East, India. Pharm. Chem. J. 2014, 1, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ariffin, I.A.; Marsi, N.; Huzaisham, N.A.; Rus, A.Z.M.; Said, A.M. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy, Energy-Dispersive X-Ray, and Physical Characteristics of Biodegradable Plastics of Banana Peel (Musa Paradisiaca) Mixed Tapioca Starch. J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2024, 18, 10127–10139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, F.; Liang, J.; Li, Q. Fast and Simple Evaluation of the Chemical Composition and Macroelements of Xylem and Bark of Sweet Cherry Branches Based on Ftir and Xps. 2023. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4334882 (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Shi, Z.; Xu, G.; Deng, J.; Dong, M.; Murugadoss, V.; Liu, C.; Shao, Q.; Wu, S.; Guo, Z. Structural Characterization of Lignin from D. sinicus by FTIR and NMR Techniques. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2019, 12, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunkar, B.; Bhukya, B. An Approach to Correlate Chemical Pretreatment to Digestibility Through Biomass Characterization by SEM, FTIR and XRD. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 802522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vârban, R.; Crișan, I.; Vârban, D.; Ona, A.; Olar, L.; Stoie, A.; Ștefan, R. Comparative FT-IR Prospecting for Cellulose in Stems of Some Fiber Plants: Flax, Velvet Leaf, Hemp and Jute. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, D.S.; Rogova, O.B.; Proskurnin, M.A. Temperature Dependences of Ir Spectra of Humic Substances of Brown Coal. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozhiarasi, V.; Natarajan, T.S. Bael Fruit Shell–Derived Activated Carbon Adsorbent: Effect of Surface Charge of Activated Carbon and Type of Pollutants for Improved Adsorption Capacity. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 14, 8761–8774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uçar, D.; Armağan, B. The Removal of Reactive Black 5 from Aqueous Solutions by Cotton Seed Shell. Water Environ. Res. 2012, 84, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwiak, T.; Filipkowska, U.; Brym, S.; Zyśk, M. The Use of Aminated Cotton Fibers as an Unconventional Sorbent to Remove Anionic Dyes from Aqueous Solutions. Cellulose 2020, 27, 3957–3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwiak, T.; Filipkowska, U.; Brym, S.; Kopeć, L. Use of Aminated Hulls of Sunflower Seeds for the Removal of Anionic Dyes from Aqueous Solutions. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 17, 1211–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsholme, P.; Stenson, L.; Sulvucci, M.; Sumayao, R.; Krause, M. Amino Acid Metabolism. In Comprehensive Biotechnology, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, H.; Yu, X. On the Protonation and Deuteration of Simple Phenols. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202201083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meot-Ner, M. The Ionic Hydrogen Bond. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 213–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, A.; Zavala-Arce, R.E.; Avila-Pérez, P.; Salazar-Rábago, J.J.; Garcia-Rivas, J.L.; Barrera-Díaz, C.E. Effect of Protonated Media on Dye Diffusion in Chitosan–Cellulose-Based Cryogel Beads. Gels 2025, 11, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, R.J.; Godínez, L.A.; Robles, I. Waste Resources Utilization for Biosorbent Preparation, Sorption Studies, and Electrocatalytic Applications. In Valorization of Wastes for Sustainable Development: Waste to Wealth; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 395–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, C.; Putra, A.; Emriadi, E.; Refilda, R.; Zein, R.; Ighalo, J.O. Eco-Friendly Removal of Indigo Carmine from Aqueous Solutions Using Avocado Peel: A Response Surface Methodology Approach. Adv. J. Chem. Sect. A 2026, 9, 556–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwiak, T.; Filipkowska, U. The Use of Rapeseed Husks to Remove Acidic and Basic Dyes from Aquatic Solutions. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwiak, T.; Filipkowska, U.; Struk-Sokołowska, J.; Bryszewski, K.; Trzciński, K.; Kuźma, J.; Ślimkowska, M. The Use of Spent Coffee Grounds and Spent Green Tea Leaves for the Removal of Cationic Dyes from Aqueous Solutions. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Józwiak, T.; Filipkowska, U.; Kowalkowska, A.; Struk-Sokoowska, J.; Werbowy, D. The Influence of Amination of Sorbent Based on Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) Husks on the Sorption Effectiveness of Reactive Black 5 Dye. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mook, W.T.; Aroua, M.K.; Szlachta, M. Palm Shell-Based Activated Carbon for Removing Reactive Black 5 Dye: Equilibrium and Kinetics Studies. Bioresources 2016, 11, 1432–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwiak, T.; Filipkowska, U.; Bednarowicz, A.; Zielińska, D.; Wiśniewska-Wrona, M. The Use of Various Types of Waste Paper for the Removal of Anionic and Cationic Dyes from Aqueous Solutions. Molecules 2024, 29, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villabona-Ortíz, Á.; Figueroa-Lopez, K.J.; Ortega-Toro, R. Kinetics and Adsorption Equilibrium in the Removal of Azo-Anionic Dyes by Modified Cellulose. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, N.; Selimi, T.; Mele, A.; Thaçi, V.; Halili, J.; Berisha, A.; Sadiku, M. Theoretical, Equilibrium, Kinetics and Thermodynamic Investigations of Methylene Blue Adsorption onto Lignite Coal. Molecules 2022, 27, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonawane, M.R.; Chhowala, T.N.; Suryawanshi, K.E.; Fegade, U.; Isai, K.A. Adsorption of MO Dyes Using Various Adsorbents: Past, Present and Future Perspective. Next Sustain. 2025, 6, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wei, Y.; Ma, Z. Modified Dual-Site Langmuir Adsorption Equilibrium Models from A GCMC Molecular Simulation. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, Z.; Acar, F.N. Adsorption of Reactive Black 5 from an Aqueous Solution: Equilibrium and Kinetic Studies. Desalination 2006, 194, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heibati, B.; Rodriguez-Couto, S.; Amrane, A.; Rafatullah, M.; Hawari, A.; Al-Ghouti, M.A. Uptake of Reactive Black 5 by Pumice and Walnut Activated Carbon: Chemistry and Adsorption Mechanisms. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2014, 20, 2939–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwiak, T.; Filipkowska, U.; Walczak, P. The Use of Aminated Wheat Straw for Reactive Black 5 Dye Removal from Aqueous Solutions as a Potential Method of Biomass Valorization. Energies 2022, 15, 6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucun, H. Equilibrium, Thermodynamic and Kinetics of Reactive Black 5 Biosorption on Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica) Seed. Sci. Res. Essays 2011, 6, 4113–4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indhu, S.; Muthukumaran, K. Removal and Recovery of Reactive Yellow 84 Dye from Wastewater and Regeneration of Functionalised Borassus Flabellifer Activated Carbon. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 3111–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, T.; Ramírez, R. Interpretation of Sorption Kinetics for Mixtures of Reactive Dyes on Wool. Turk. J. Chem. 2005, 29, 617–625. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, M.; Hassani, A.J.; Mohamed, A.R.; Najafpour, G.D. Removal of Rhodamine B from Aqueous Solution Using Palm Shell-Based Activated Carbon: Adsorption and Kinetic Studies. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2010, 55, 5777–5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parab, H.; Sudersanan, M.; Shenoy, N.; Pathare, T.; Vaze, B. Use of Agro-Industrial Wastes for Removal of Basic Dyes from Aqueous Solutions. Clean 2009, 37, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.J.; Artola, A.; Balaguer, M.D.; Rigola, M. Activated Carbons Developed from Surplus Sewage Sludge for the Removal of Dyes from Dilute Aqueous Solutions. Chem. Eng. J. 2003, 94, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, N.A.I.; Zainudin, N.F.; Ali, U.F.M. Adsorption of Basic Red 46 Using Sea Mango (Cerbera odollam) Based Activated Carbon. AIP Conf. Proc. 2015, 1660, 070068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laasri, L.; Elamrani, M.K.; Cherkaoui, O. Removal of Two Cationic Dyes from a Textile Effluent by Filtration-Adsorption on Wood Sawdust. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2007, 14, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, J.; Gao, W. Reviewing Textile Wastewater Produced by Industries: Characteristics, Environmental Impacts, and Treatment Strategies. Water Sci. Technol. 2022, 85, 2076–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmen, Z.; Daniel, S. Textile Organic Dyes–Characteristics, Polluting Effects and Separation/Elimination Procedures from Industrial Effluents–A Critical Overview. In Organic Pollutants Ten Years After the Stockholm Convention-Environmental and Analytical Update; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, O.; Iwaszczuk, N.; Kharebava, T.; Bejanidze, I.; Pohrebennyk, V.; Nakashidze, N.; Petrov, A. Neutralization of Industrial Water by Electrodialysis. Membranes 2021, 11, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkika, D.A.; Tolkou, A.K.; Katsoyiannis, I.A.; Kyzas, G.Z. The Adsorption-Desorption-Regeneration Pathway to a Circular Economy: The Role of Waste-Derived Adsorbents on Chromium Removal. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 368, 132996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda-Mbanga, B.G.; Onotu, O.P.; Tywabi-Ngeva, Z. Advantages of the Reuse of Spent Adsorbents and Potential Applications in Environmental Remediation: A Review. Green Anal. Chem. 2024, 11, 100156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, A.; Jóźwiak, T.; Zieliński, M. The Possibility of Using Waste from Dye Sorption for Methane Production. Energies 2024, 17, 4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januszewicz, K.; Kazimierski, P.; Cymann-Sachajdak, A.; Hercel, P.; Barczak, B.; Wilamowska-Zawłocka, M.; Kardaś, D.; Łuczak, J. Conversion of Waste Biomass to Designed and Tailored Activated Chars with Valuable Properties for Adsorption and Electrochemical Applications. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 96977–96992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | Content (Range) [%] |

|---|---|

| Starch | 23.0–52.1 |

| Cellulose | 32.4–55.0 |

| Hemicellulose | 10.0–12.0 |

| Monosaccharides (soluble) | 1.0–7.3 |

| Lignin | 14.0–20.0 |

| Proteins | 8.0–14.2 |

| Lipids | 1.0–2.6 |

| Ash and minerals | 2.1–9.1 |

| Dye Name | Reactive Black 5 (RB5) | Reactive Yellow 84 (RY84) | Basic Violet 10 (BV10) | Basic Red 46 (BR46) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other trade names | Diamira Black B, Begazol Black B, Remazol Black B | Lamafix Yellow HER, Apollocion Yellow H-E4R, Active Yellow HE-4R | Basic Red RB, Violet B, Rhodamine B, | Sevron Fast Red GRL, Cationic Red X-GRL, Anilan Red GRL |

| Chemical formula | C26H21N5Na4O19S6 | C56H38Cl2N14Na6O20S6 | C28H31ClN2O3 | C18H21BrN6 |

| Molecular weight | 991.8 g/mol | 1628.2 g/mol | 479.0 g/mol | 321.4 g/mol |

| Dye class | double azo dye | double azo dye | xanthene dye | single azo dye |

| Dye type | anionic (reactive) | anionic (reactive) | cationic | cationic |

| λmax | 600 nm | 356 nm | 554 nm | 530 nm |

| Uses |

dyeing wool and

cotton | dyeing polyester, cotton, rayon | dyeing textiles, paper, leather |

dyeing leather,

paper, wool |

| Dye | Ionic strength I [mol/L] of dye solutions (50 mg/L) at different pH | ||||

| pH 2 | pH 3 | pH 4 | pH 5 | pH 6 | |

| RB5 | 1.05 × 10−2 | 1.50 × 10−3 | 6.04 × 10−4 | 5.14 × 10−4 | 5.05 × 10−4 |

| RY84 | 1.06 × 10−2 | 1.62 × 10−3 | 7.24 × 10−4 | 6.34 × 10−4 | 6.25 × 10−4 |

| BV10 | 1.02 × 10−2 | 1.16 × 10−3 | 2.56 × 10−4 | 1.66 × 10−4 | 1.57 × 10−4 |

| BR46 | 1.01 × 10−2 | 1.10 × 10−3 | 2.04 × 10−4 | 1.14 × 10−4 | 1.05 × 10−4 |

| Dye | Ionic strength I [mol/L] of dye solutions (50 mg/L) at different pH | ||||

| pH 7 | pH 8 | pH 9 | pH 10 | pH 11 | |

| RB5 | 5.04 × 10−4 | 5.05 × 10−4 | 5.14 × 10−4 | 6.04 × 10−4 | 1.50 × 10−3 |

| RY84 | 6.24 × 10−4 | 6.25 × 10−4 | 6.34 × 10−4 | 7.24 × 10−4 | 1.62 × 10−3 |

| BV10 | 1.56 × 10−4 | 1.57 × 10−4 | 1.66 × 10−4 | 2.56 × 10−4 | 1.16 × 10−3 |

| BR46 | 1.04 × 10−4 | 1.05 × 10−4 | 1.14 × 10−4 | 2.04 × 10−4 | 1.10 × 10−3 |

| Dye | Dye Conc. | Pseudo-First-Order Model | Pseudo-Second-Order Model | Exp. Data | Equil. Time | ||

| k1 | qe,(cal.) | k2 | qe,(cal.) | qe,exp | |||

| [mg/L] | [1/min] | [mg/g] | [g/mg*min] | [mg/g] | [mg/g] | [min] | |

| RB5 | 50 | 0.0631 ± 0.0041 | 4.35 ± 0.04 | 0.0225 ± 0.0016 | 4.65 ± 0.06 | 4.42 ± 0.21 | 180 |

| 200 | 0.0224 ± 0.0025 | 13.84 ± 0.45 | 0.0015 ± 0.0002 | 16.61 ± 0.45 | 14.66 ± 0.63 | 240 | |

| 500 | 0.0162 ± 0.0017 | 18.93 ± 0.60 | 0.0008 ± 0.0001 | 23.02 ± 0.71 | 19.35 ± 0.69 | 270 | |

| RY84 | 50 | 0.0635 ± 0.0027 | 4.32 ± 0.04 | 0.0197 ± 0.0015 | 4.78 ± 0.06 | 4.43 ± 0.10 | 180 |

| 200 | 0.0209 ± 0.0022 | 14.47 ± 0.43 | 0.0015 ± 0.0002 | 17.02 ± 0.41 | 14.91 ± 0.58 | 240 | |

| 500 | 0.0160 ± 0.0016 | 19.47 ± 0.61 | 0.0007 ± 0.0001 | 23.75 ± 0.71 | 20.04 ± 0.80 | 270 | |

| BV10 | 10 | 0.0160 ± 0.0013 | 0.71 ± 0.02 | 0.0193 ± 0.0014 | 0.87 ± 0.02 | 0.71 ± 0.04 | 210 |

| 50 | 0.0179 ± 0.0014 | 2.90 ± 0.07 | 0.0057 ± 0.0004 | 3.50 ± 0.07 | 2.95 ± 0.26 | 270 | |

| 200 | 0.0139 ± 0.0015 | 6.73 ± 0.24 | 0.0017 ± 0.0003 | 8.39 ± 0.32 | 6.79 ± 0.66 | 270 | |

| BR46 | 50 | 0.1268 ± 0.0049 | 4.30 ± 0.04 | 0.0683 ± 0.0085 | 4.44 ± 0.20 | 4.28 ± 0.10 | 45 |

| 200 | 0.0730 ± 0.0033 | 14.76 ± 0.16 | 0.0110 ± 0.0007 | 15.61 ± 0.38 | 14.88 ± 0.71 | 90 | |

| 500 | 0.0354 ± 0.0028 | 23.44 ± 0.45 | 0.0019 ± 0.0001 | 26.10 ± 0.23 | 23.94 ± 1.06 | 210 | |

| Model Evaluation Metrics | |||||||

| Dye | Dye Conc. | Pseudo-First-Order Model | Pseudo-Second-Order Model | ||||

| [mg/L] | R2 | RMSE | AIC | R2 | RMSE | AIC | |

| RB5 | 50 | 0.9948 | 0.1479 | −34.23 | 0.9955 | 0.0875 | −44.72 |

| 200 | 0.9727 | 0.6305 | −9.33 | 0.9919 | 0.2452 | −30.05 | |

| 500 | 0.9760 | 0.9740 | 3.33 | 0.9908 | 0.4640 | −16.01 | |

| RY84 | 50 | 0.9963 | 0.1428 | −29.92 | 0.9964 | 0.0921 | −37.28 |

| 200 | 0.9754 | 0.5049 | −11.07 | 0.9938 | 0.2760 | −23.88 | |

| 500 | 0.9769 | 1.0556 | 5.31 | 0.9914 | 0.6130 | −7.75 | |

| BV10 | 10 | 0.9921 | 0.0404 | −60.15 | 0.9971 | 0.0276 | −67.80 |

| 50 | 0.9864 | 0.1316 | −41.30 | 0.9958 | 0.0625 | −55.58 | |

| 200 | 0.9769 | 0.3807 | −19.15 | 0.9893 | 0.2370 | −30.62 | |

| BR46 | 50 | 0.9945 | 0.1922 | −14.07 | 0.9952 | 0.0917 | −8.92 |

| 200 | 0.9948 | 0.1479 | −34.23 | 0.9955 | 0.0875 | −44.72 | |

| 500 | 0.9727 | 0.6305 | −9.33 | 0.9919 | 0.2452 | −30.05 | |

| Dye | Dye Conc. | Phase I | Phase II | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kd1 | Duration | R2 | kd2 | Duration | R2 | ||

| [mg/L] | [mg/(g*min0.5)] | [min] | - | [mg/(g*min0.5)] | [min] | - | |

| RB5 | 50 | 0.6142 | 45 | 0.9846 | 0.0575 | 135 | 0.9524 |

| 200 | 1.2535 | 60 | 0.9984 | 0.6339 | 180 | 0.9917 | |

| 500 | 1.3533 | 150 | 0.9970 | 0.6384 | 120 | 0.9836 | |

| RY84 | 50 | 0.6147 | 45 | 0.9865 | 0.0600 | 135 | 0.9463 |

| 200 | 1.2782 | 60 | 0.9986 | 0.6656 | 180 | 0.9876 | |

| 500 | 1.3912 | 150 | 0.9969 | 0.6913 | 120 | 0.9711 | |

| BV10 | 10 | 0.0545 | 90 | 0.9918 | 0.0448 | 120 | 0.9872 |

| 50 | 0.2270 | 120 | 0.9931 | 0.0992 | 150 | 0.9553 | |

| 200 | 0.4607 | 150 | 0.9980 | 0.2596 | 120 | 0.9956 | |

| BR46 | 50 | 0.9134 | 20 | 0.9965 | 0.1134 | 45 | 0.9951 |

| 200 | 2.4494 | 30 | 0.9978 | 0.4114 | 60 | 0.8992 | |

| 500 | 2.5834 | 60 | 0.9920 | 0.6171 | 150 | 0.9814 | |

| Dye | Langmuir 1 Model | Freundlich Model | |||||||

| Qmax | Kc | k | n | ||||||

| [mg/g] | [L/mg] | - | - | ||||||

| RB5 | 20.85 ± 0.33 | 0.0540 ± 0.0042 | 4.177 ± 0.935 | 3.450 ± 0.045 | |||||

| RY84 | 21.63 ± 0.34 | 0.0514 ± 0.0038 | 4.15 ± 0.902 | 3.369 ± 5.630 | |||||

| BV10 | 10.28 ± 0.24 | 0.0162 ± 0.0014 | 1.098 ± 0.227 | 2.772 ± 0.313 | |||||

| BR46 | 27.15 ± 0.874 | 0.0285 ± 0.0034 | 3.286 ± 0.518 | 2.671 ± 0.228 | |||||

| Dye | Langmuir 2 Model | ||||||||

| Qmax | b1 | K1 | b2 | K2 | |||||

| [mg/g] | [mg/g] | [L/mg] | [mg/g] | [L/mg] | |||||

| RB5 | 20.91 ± 23,977 | 20.46 ± 16,954 | 0.0547 ± 1031 | 0.44 ± 16,954 | 0.0547 ± 47,651 | ||||

| RY84 | 21.90 ± 45.39 | 19.75 ± 33.02 | 0.0567 ± 0.0627 | 2.15 ± 31.15 | 0.0139 ± 0.1992 | ||||

| BV10 | 12.01 ± 23.64 | 6.34 ± 23.28 | 0.0037 ± 0.0115 | 5.67 ± 4.09 | 0.0370 ± 0.0115 | ||||

| BR46 | 31.88 ± 8.13 | 20.27 ± 4.19 | 0.0079 ± 0.0685 | 11.60 ± 6.97 | 0.0953 ± 0.0684 | ||||

| Model Evaluation Metrics | |||||||||

| Dye | Langmuir 1 Model | Langmuir 2 Model | Freundlich Model | ||||||

| R2 | RMSE | AIC | R2 | RMSE | AIC | R2 | RMSE | AIC | |

| RB5 | 0.9940 | 0.4795 | −12.22 | 0.9940 | 0.4795 | −12.22 | 0.9029 | 2.0104 | 19.33 |

| RY84 | 0.9966 | 0.5970 | −0.12 | 0.9969 | 0.5510 | 2.21 | 0.9017 | 2.1120 | 21.41 |

| BV10 | 0.9927 | 0.3950 | −6.23 | 0.9971 | 0.3750 | −5.45 | 0.9120 | 0.7780 | 6.94 |

| BR46 | 0.9889 | 1.1890 | 8.61 | 0.9977 | 0.8400 | 2.21 | 0.9767 | 1.3460 | 11.02 |

| Dye | Sorbent | Qmax [mg/g] | pH of Sorption | Time of Sorption [min] | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RB5 | Activated carbon (powder) | 58.8 | - | - | [80] |

| Activated carbon from palm shells | 25.1 | 2 | 300 | [74] | |

| Potato Peels | 20.9 | 2 | 270 | This work | |

| Activated carbon from wood (walnut) | 19.3 | 5 | 400 | [81] | |

| Wheat straw | 15.7 | 3 | 195 | [82] | |

| Rapeseed husks | 15.2 | 3 | 180 | [33] | |

| Eriobotrya japonica seed husks | 13.8 | 3 | 150 | [83] | |

| Cotton seed husks | 12.9 | 2 | 30 | [62] | |

| RY84 | Activated carbon from the Borassus flabellifer plant | 40.0 | - | - | [84] |

| Potato Peels | 21.6 | 2 | 270 | This work | |

| Cotton fibers | 15.9 | 2 | 240 | [63] | |

| Rapeseed husks | 13.7 | 3 | 180 | [33] | |

| Wool | 11.0 | 7 | 180 | [85] |

| Dye | Sorbent | Qmax [mg/g] | pH of Sorption | Time of Sorption [min] | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BV10 | Commercial active carbon powder | 72.5 | 4 | 1440 | [28] |

| Activated carbon (palm shell-based) | 30.0 | 3 | - | [86] | |

| Spent green tea leaves | 26.7 | 3 | 240 | [72] | |

| Corrugated cardboard (used) | 24.7 | 2 | 210 | [75] | |

| Rapeseed husks | 20.9 | 3 | 180 | [71] | |

| Sugar cane fiber | 10.4 | - | - | [87] | |

| Potato Peels | 10.3 | 2 | 270 | This work | |

| BR46 | Activated carbon “Chemviron” | 106.0 | 7.4 | 120 | [88] |

| Cerbera odollam biomass activated carbon | 65.7 | 7 | 90 | [89] | |

| Rapeseed husks | 59.1 | 6 | 180 | [71] | |

| Spent green tea leaves | 58.0 | 6 | 240 | [72] | |

| Potato Peels | 27.2 | 6 | 210 | This work | |

| Office paper (used) | 19.6 | 6 | 90 | [75] | |

| Wood sawdust | 19.2 | - | 120 | [90] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jóźwiak, T.; Filipkowska, U.; Nowicka, A.; Kaźmierczak, J. Application of Potato Peels as an Unconventional Sorbent for the Removal of Anionic and Cationic Dyes from Aqueous Solutions. Materials 2026, 19, 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010185

Jóźwiak T, Filipkowska U, Nowicka A, Kaźmierczak J. Application of Potato Peels as an Unconventional Sorbent for the Removal of Anionic and Cationic Dyes from Aqueous Solutions. Materials. 2026; 19(1):185. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010185

Chicago/Turabian StyleJóźwiak, Tomasz, Urszula Filipkowska, Anna Nowicka, and Jarosław Kaźmierczak. 2026. "Application of Potato Peels as an Unconventional Sorbent for the Removal of Anionic and Cationic Dyes from Aqueous Solutions" Materials 19, no. 1: 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010185

APA StyleJóźwiak, T., Filipkowska, U., Nowicka, A., & Kaźmierczak, J. (2026). Application of Potato Peels as an Unconventional Sorbent for the Removal of Anionic and Cationic Dyes from Aqueous Solutions. Materials, 19(1), 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010185