Correlations Between Carbon Structure and Properties by XRD and Raman Structural Studies During Coke Formation in Various Rank Coals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Coal Selection and Analysis

2.2. Sample Preparation and Method

2.3. Analysis of Coal Samples

2.3.1. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TG) Analysis Method

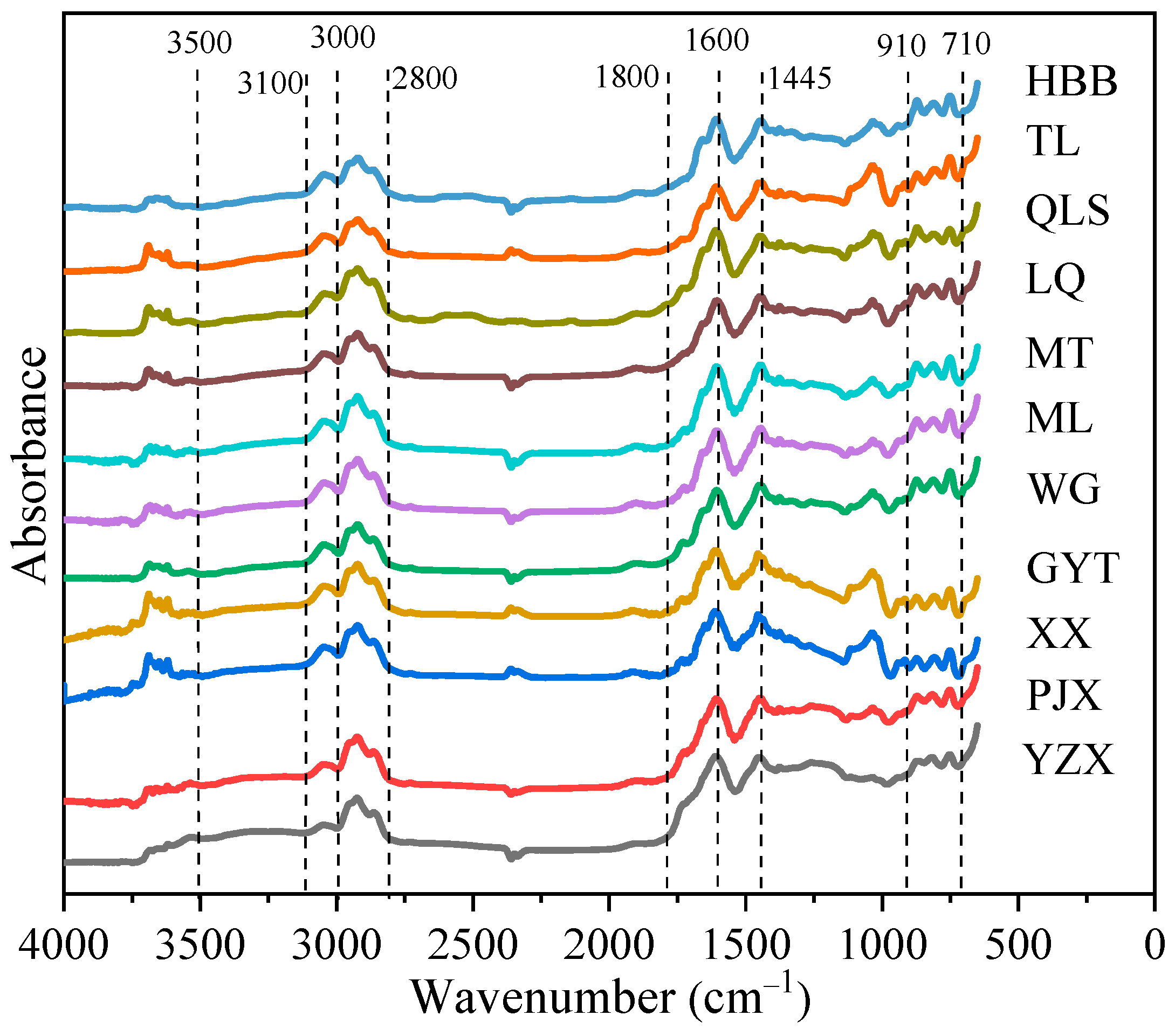

2.3.2. FTIR Analysis Method

2.3.3. XRD Analysis of Samples

2.3.4. Raman Analysis of Samples

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Analysis of Different Coals During Pyrolysis

3.1.1. TG Analysis

3.1.2. FTIR Analysis

3.2. XRD Analysis of Different Rank Coals During the Coking Process

3.2.1. XRD Analysis

3.2.2. The Changes in the Carbon Structure of Different Rank Coals

3.3. Changes in Carbon Structure Parameters with Coal Rank During the Coking Process

3.3.1. Relationship Between Coal Rank and Lc During Coke Formation

3.3.2. Relationship Between Coal Rank and La During Coke Formation

3.4. Changes in Carbon Structures with Coke Properties During the Coking Process

3.5. Raman Analysis of Different Rank Coals During the Coking Process

3.5.1. Raman Analysis

3.5.2. Changes in the Structure Parameters of Different Rank Coals

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Granda, M.; Blanco, C.; Alvarez, P.; Patrick, J.W.; Menéndez, R. Chemicals from coal coking. Chem. Rev. 2013, 114, 1608–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.B.; Shen, Y.F.; Guo, J.; Jin, X.; Wang, M.J.; Xie, W.; Chang, L.P. A study of coking mechanism based on the transformation of coal structure. Fuel 2022, 328, 125360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Shen, Y.F.; Wang, M.J.; Xie, W.; Kong, J.; Chang, L.P.; Bao, W.R.; Xie, K.C. Impact of chemical structure of coal on coke quality produced by coals in the similar category. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2022, 162, 105432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Z.; Li, M.F.; Zeng, F.G. Control of chemical structure on the characteristics of micropore structure in medium-rank coals. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 228, 107162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.J.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, X.F.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, H. Relevance between various phenomena during coking coal carbonization. Part 2: Phenomenon occurring in the plastic layer formed during carbonization of a coking coal. Fuel 2019, 253, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Xu, R.; Zhang, J.; Daghagheleh, O.; Schenk, J.; Li, C.; Wang, W. A comprehensive review of characterization methods for metallurgical coke structures. Materials 2022, 15, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.J.; Khanna, R.; Zhang, J.L.; Barati, M.; Liu, Z.J.; Xu, T.; Yang, T.J.; Sahajwalla, V. Comprehensive investigation of various structural features of bituminous coals using advanced analytical techniques. Energy Fuels 2015, 29, 7178–7189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Yu, J.L.; Mahoney, M.; Tahmasebi, A.; Stanger, R.; Wall, T.; Lucas, J. In-situ study of plastic layers during coking of six Australian coking coals using a lab-scale coke oven. Fuel Process. Technol. 2019, 188, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.J.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, X.F.; Yang, S.T.; Wu, H.L.; Zhang, S.; Sun, J.F. Relevance between various phenomena during coking coal carbonization. Part 3: Understanding the properties of the plastic layer during coal carbonization. Fuel 2021, 292, 120371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.X.; Lee, S.; Tahmasebi, A.; Liu, M.J.; Zhang, T.T.; Bai, J.; Tian, L.; Yu, J.L. Mechanism of carbon structure transformation in plastic layer and semi-coke during coking of Australian metallurgical coals. Fuel 2022, 315, 123205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnichenko, D.; Shmeltser, K.; Kormer, M. Factors Affecting the formation the carbon structure of coke and the method of stabilizing its physical and mechanical properties. C—J. Carbon Res. 2023, 9, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.L.; Qi, Y.X.; Tian, L.; Dou, J.X.; Appiah, J.; Wang, J.W.; Zhu, R.Z.; Chen, X.X.; Yu, J.L. Evolution of carbon structure and cross-linking structure during coking process of coking coal. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2024, 182, 106670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, A.; Cao, D.; Wei, Y.; Ding, L. Differences in macromolecular structure evolution during the pyrolysis of vitrinite and inertinite based on in situ FTIR and XRD measurements. Energies 2022, 15, 5334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.G.; Zeng, F.G.; Li, C.Y.; Xu, Q.Y.; Chen, P.F. Insight into the molecular structural evolution of a series of medium-rank coals from China by XRD, Raman and FTIR. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1303, 137616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Sahajwalla, V.; Kong, C.; Harris, D. Quantitative X-ray diffraction analysis and its application to various coals. Carbon 2001, 39, 1821–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonibare, O.O.; Haeger, T.; Foley, S.F. Structural characterization of Nigerian coals by X-ray diffraction, Raman and FTIR spectroscopy. Energy 2010, 35, 5347–5353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.W.; Pang, K.L.; Wu, J.; Liang, C. Coke characteristics and formation mechanism based on the hot tamping coking. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2022, 161, 105381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 212-2008; Proximate Analysis of Coal. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine; Standardization Administration of PRC: Beijing, China, 2009.

- GB/T 6948-2008; Method of Determining Microscopically the Reflectance of Vitrinite in Coal. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine; Standardization Administration of PRC: Beijing, China, 2009.

- GB/T 4000-2017; Determination of Coke Reactivity Index (CRI) and Coke Strength After Reaction (CSR). General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine; Standardization Administration of PRC: Beijing, China, 2018.

- GB/T 1996-2017; Coke for metallurgy. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine; Standardization Administration of PRC: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Yan, J.C.; Lei, Z.P.; Li, Z.K.; Wang, Z.C.; Ren, S.B.; Kang, S.G.; Wang, X.L.; Shui, H.F. Molecular structure characterization of low-medium rank coals via XRD, solid state 13C NMR and FTIR spectroscopy. Fuel 2020, 268, 117038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.Y.; Chen, S.C.; Han, F.; Wu, D. An experimental study on the evolution of aggregate structure in coals of different ranks by in situ X-ray diffractometry. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 8720–8726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah, J.; Tian, L.; Dou, J.X.; Chen, Y.X.; Chen, X.X.; Xu, X.L.; Yu, J.L. Investigation into the impact of coal blending on the carbon structure of chars obtained from Chinese coals during coking. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2024, 179, 106504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Liu, G.J.; Sun, R.Y.; Chen, S.C. Influences of magmatic intrusion on the macromolecular and pore structures of coal: Evidences from Raman spectroscopy and atomic force microscopy. Fuel 2014, 119, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.Q.; Liu, X.F.; Nie, B.S.; Song, D.Z. FTIR and Raman spectroscopy characterization of functional groups in various rank coals. Fuel 2017, 206, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenvold, R.J.; Dubow, J.B.; Rajeshwar, K. Thermal analyses of Ohio bituminous coals. Thermochim. Acta 1982, 53, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, P.C.; Snyder, R.W.; Starsinic, M.; Coleman, M.M.; Davis, A. Concerning the application of FT-IR to the study of coal: A critical assessment of band assignments and the application of spectral analysis programs. Appl. Spectrosc. 1981, 35, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.Y.; Gupta, S.; Yu, J.L.; Jiang, Y.; Koshy, P.; Sorrell, C.; Shen, Y.S. Effects of kaolinite addition on the thermoplastic behaviour of coking coal during low temperature pyrolysis. Fuel Process. Technol. 2017, 167, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, A.J.; Tian, S.X.; Lin, H.Y. Analysis of outburst coal structure characteristics in Sanjia coal mine based on FTIR and XRD. Energies 2022, 15, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Liu, Q.F.; Cheng, H.F.; Hu, M.S.; Zhang, S. Classification and carbon structural transformation from anthracite to natural coaly graphite by XRD, Raman spectroscopy, and HRTEM. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 249, 119286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.Y.; Lu, L.B.; Zhang, D.M.; Wei, W.W.; Jin, H.; Guo, L.J. Effects of alkaline metals on the reactivity of the carbon structure after partial supercritical water gasification of coal. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 13916–13923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Li, G.Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.P.; Ding, Z.Z.; Guo, R.; Cheng, H.; Liang, Y.H. Molecular basis for coke strength: Stacking-fault structure of wrinkled carbon layers. Carbon 2020, 162, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Tang, Y.; Che, Q.; Ma, P.; Luo, P.; Lu, X.; Dong, M. Effects of coal rank and macerals on the structure characteristics of coal-based graphene materials from anthracite in Qinshui coalfield. Minerals 2022, 12, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.B.; Toth, P.; Song, Y.; Li, W. Staged evolutionary features of the aromatic structure in high volatile A bituminous coal (hvAb) during gold tube pyrolysis experiments. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2025, 297, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.W.; Zhang, Z.; Han, H.Y.; He, X.F.; Zhang, Y.G.; Zhou, A.N.; Jin, L.J.; Hu, H.Q. Insight into evolution characteristics of pyrolysis products of HLH and HL coal with Py-VUVPI-MS and DFT. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2024, 183, 106829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Huang, W.F.; Li, Z.H.; Chang, L.P.; Li, D.F.; Chen, R.C.; Lv, Q.; Zhao, Y.X.; Lv, B.L. Small furnace for the small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and wide angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) characterization of the high temperature carbonization of coal. Instrum. Sci. Technol. 2021, 49, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.V.; Choudhary, A.K.S.; Adak, A.K.; Maity, K.S. An investigation on demineralization induced modifications in the macromolecular structure and its influence on the thermal behavior of coking and non-coking coal. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1274, 134520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah, J.; Tian, L.; Xu, X.L.; Dou, J.X.; Wang, J.W.; Chen, X.X.; Yu, J.L. Comparative study of the carbon structure of chars formed from coal with plastic waste and coal tar pitch additives. Carbon Lett. 2025, 35, 749–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidena, K.; Murata, S.; Nomura, M. Studies on the chemical structural change during carbonization process. Energy Fuels 1996, 10, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, R.E. Crystallite growth in graphitizing and non-graphitizing carbons. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1951, 209, 196–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kida, T.; Tanaka, R.; Hiejima, Y.; Nitta, K.H.; Shiono, T. Improving the strength of polyethylene solids by simple controlling of the molecular weight distribution. Polymer 2021, 218, 123526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Hillbrick, L.; Abbott, A.; Lynch, P.; Mota-Santiago, P.; Pierlot, A.P. High molecular weight improves microstructure and mechanical properties of polyacrylonitrile based carbon fibre precursor. Polymer 2022, 247, 124753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| YZX | PJX | XX | GYT | WG | ML | MT | LQ | QLS | TL | HHB | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | GC | 1/3CC | FC | CC | FC | CC | CC | CC | CC | CC | LC | |

| Proximate analysis (wt%, ad) | M | 2.23 | 1.30 | 0.97 | 0.61 | 0.4 | 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.9 | 0.94 | 0.51 | 0.93 |

| A | 7.89 | 8.87 | 9.28 | 10.23 | 9.91 | 9.19 | 9.33 | 8.94 | 9.96 | 10.23 | 11.51 | |

| V | 32.49 | 31.30 | 29.09 | 20.44 | 22.94 | 22.67 | 20.93 | 18.86 | 19.74 | 19.8 | 13.82 | |

| FC | 57.39 | 58.53 | 60.66 | 68.72 | 66.75 | 67.25 | 69.02 | 71.3 | 69.36 | 69.46 | 73.74 | |

| Ultimate analysis (wt%, daf) | C | 88.52 | 85.78 | 87.29 | 84.28 | 90.91 | 86.79 | 90.5 | 88.75 | 86.63 | 88.4 | 93.02 |

| H | 4.71 | 4.68 | 4.5 | 3.06 | 4.27 | 5.61 | 3.94 | 3.78 | 3.82 | 5.25 | 4.07 | |

| N | 1.92 | 1.39 | 1.79 | 2.03 | 1.69 | 2.13 | 1.76 | 1.15 | 1.89 | 1.75 | 1.58 | |

| S | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 1.34 | 0.8 | 0.91 | 0.5 | 1.25 | 0.39 | 1.29 | 0.37 | |

| O * | 4.38 | 7.78 | 5.79 | 9.29 | 2.33 | 4.56 | 3.3 | 5.06 | 7.27 | 3.31 | 0.96 | |

| Ro max | 0.744 | 0.959 | 1.199 | 1.308 | 1.31 | 1.338 | 1.343 | 1.398 | 1.427 | 1.465 | 1.831 | |

| Coke properties | M40 | 65.2 | 84.0 | 82.4 | 82.4 | 85.2 | 90.9 | 84.8 | 84.4 | 87.6 | 89.3 | / |

| M10 | 27.2 | 8.0 | 8.8 | 6.8 | 9.2 | 6.3 | 8.4 | 8.8 | 7.2 | 6.7 | / | |

| CRI | 59.4 | 25.4 | 29 | 24.3 | 33.1 | 18.25 | 23.1 | 23 | 20.3 | 15.1 | / | |

| CSR | 23.6 | 62.7 | 57.7 | 66.1 | 55.7 | 69.25 | 59.4 | 63.3 | 71.8 | 73.0 | / | |

| Coke grade | - | II | III | I | III | I | II | III | II | I | - |

| Center/cm−1 | Bands | Assignment | Band Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1590 | G | Aromatic ring quadrant breathing; alkene C=C | sp2 |

| 1540 | D2 | Amorphous carbon structures; aromatics with 3–5 rings | sp2 |

| 1465 | D3 | Aryl–alkyl ether; para-aromatics | sp2, sp3 |

| 1380 | D1 | C=C between aromatic rings and aromatics with not less than 6 rings | sp2 |

| 1185 | D4 | Caromatic=Calkyl; aromatic (aliphatic) ethers; C=C on hydroaromatic rings; hexagonal diamond carbon sp3; C-H on aromatic rings | sp2, sp3 |

| γ | 002 | 100 | Lc/nm | La/nm | d002/nm | N | n | fa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2θ/° | FWHM | Area | 2θ/° | FWHM | Area | 2θ/° | FWHM | Area | |||||||

| Raw | 20.44 | 7.40 | 7250 | 25.22 | 5.16 | 9879 | 45.28 | 7.21 | 841 | 1.649 | 2.444 | 0.3532 | 5.7 | 10.3 | 0.5767 |

| 400 °C | 20.41 | 6.35 | 5931 | 25.15 | 5.09 | 9687 | 44.81 | 8.20 | 951 | 1.671 | 2.144 | 0.3540 | 5.7 | 10.5 | 0.6203 |

| 450 °C | 20.53 | 5.89 | 6107 | 25.31 | 4.91 | 9858 | 44.24 | 8.43 | 1104 | 1.732 | 2.083 | 0.3518 | 5.9 | 11.2 | 0.6175 |

| 500 °C | 21.37 | 7.43 | 6056 | 25.45 | 4.75 | 10,758 | 44.71 | 7.79 | 969 | 1.791 | 2.255 | 0.3500 | 6.1 | 12.0 | 0.6398 |

| 600 °C | 21.42 | 6.22 | 4387 | 25.55 | 4.58 | 10,724 | 44.07 | 4.67 | 696 | 1.859 | 3.758 | 0.3487 | 6.3 | 12.8 | 0.7097 |

| 700 °C | 21.43 | 5.29 | 4725 | 25.71 | 4.50 | 11,335 | 43.44 | 3.58 | 1018 | 1.892 | 4.893 | 0.3465 | 6.5 | 13.4 | 0.7058 |

| 800 °C | 21.43 | 5.02 | 4376 | 25.79 | 4.46 | 13,792 | 43.51 | 3.12 | 1132 | 1.910 | 5.615 | 0.3455 | 6.5 | 13.6 | 0.7591 |

| 900 °C | 21.61 | 4.13 | 3858 | 25.80 | 4.41 | 13,637 | 43.53 | 3.36 | 1456 | 1.931 | 5.204 | 0.3453 | 6.6 | 13.9 | 0.7795 |

| 1000 °C | 22.13 | 3.64 | 3738 | 25.91 | 4.40 | 15,405 | 43.39 | 3.24 | 1489 | 1.938 | 5.398 | 0.3438 | 6.6 | 14.1 | 0.8047 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tian, L.; Dou, J.; Chen, X.; Yu, J. Correlations Between Carbon Structure and Properties by XRD and Raman Structural Studies During Coke Formation in Various Rank Coals. Materials 2026, 19, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010168

Tian L, Dou J, Chen X, Yu J. Correlations Between Carbon Structure and Properties by XRD and Raman Structural Studies During Coke Formation in Various Rank Coals. Materials. 2026; 19(1):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010168

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Lu, Jinxiao Dou, Xingxing Chen, and Jianglong Yu. 2026. "Correlations Between Carbon Structure and Properties by XRD and Raman Structural Studies During Coke Formation in Various Rank Coals" Materials 19, no. 1: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010168

APA StyleTian, L., Dou, J., Chen, X., & Yu, J. (2026). Correlations Between Carbon Structure and Properties by XRD and Raman Structural Studies During Coke Formation in Various Rank Coals. Materials, 19(1), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010168