Effects of Phosphogypsum–Recycled Aggregate Solid Waste Base on Properties of Vegetation Concrete

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

2.1.1. Cementitious Materials

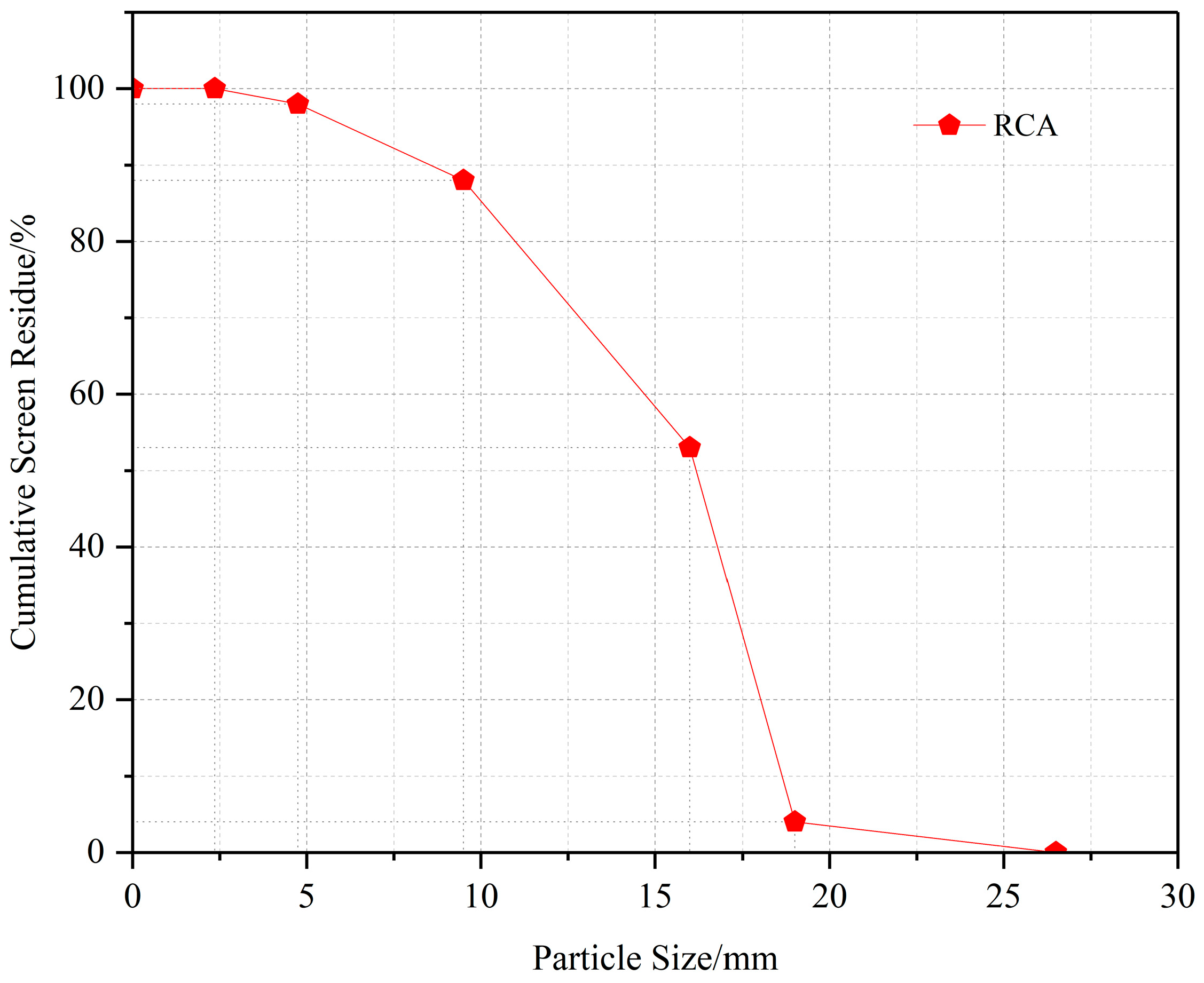

2.1.2. Coarse Aggregates

2.1.3. Admixtures

2.2. Mix Ratio Design

2.2.1. Theoretical Method

- WG: Dosage of coarse aggregate per unit volume (kg/m3);

- ρG,c: Compacted bulk density of recycled coarse aggregates (kg/m3);

- α: Reduction coefficient, taken as 0.98.

- WJ: Dosage of cementitious paste per unit volume of concrete (kg/m3);

- ρG: Apparent density of coarse aggregates (kg/m3);

- Rvoid: Designed porosity value (decimal);

- ρl: Density of cementitious paste (kg/m3).

- WB: Dosage of cementitious materials per unit volume of concrete (kg/m3);

- W/B: Water–binder ratio (decimal).

2.2.2. Test Mix Ratio

2.3. Test Methods

2.3.1. Specimen Preparation

2.3.2. Mechanical Performance and Setting Time Test

2.3.3. Pore pH Value Test

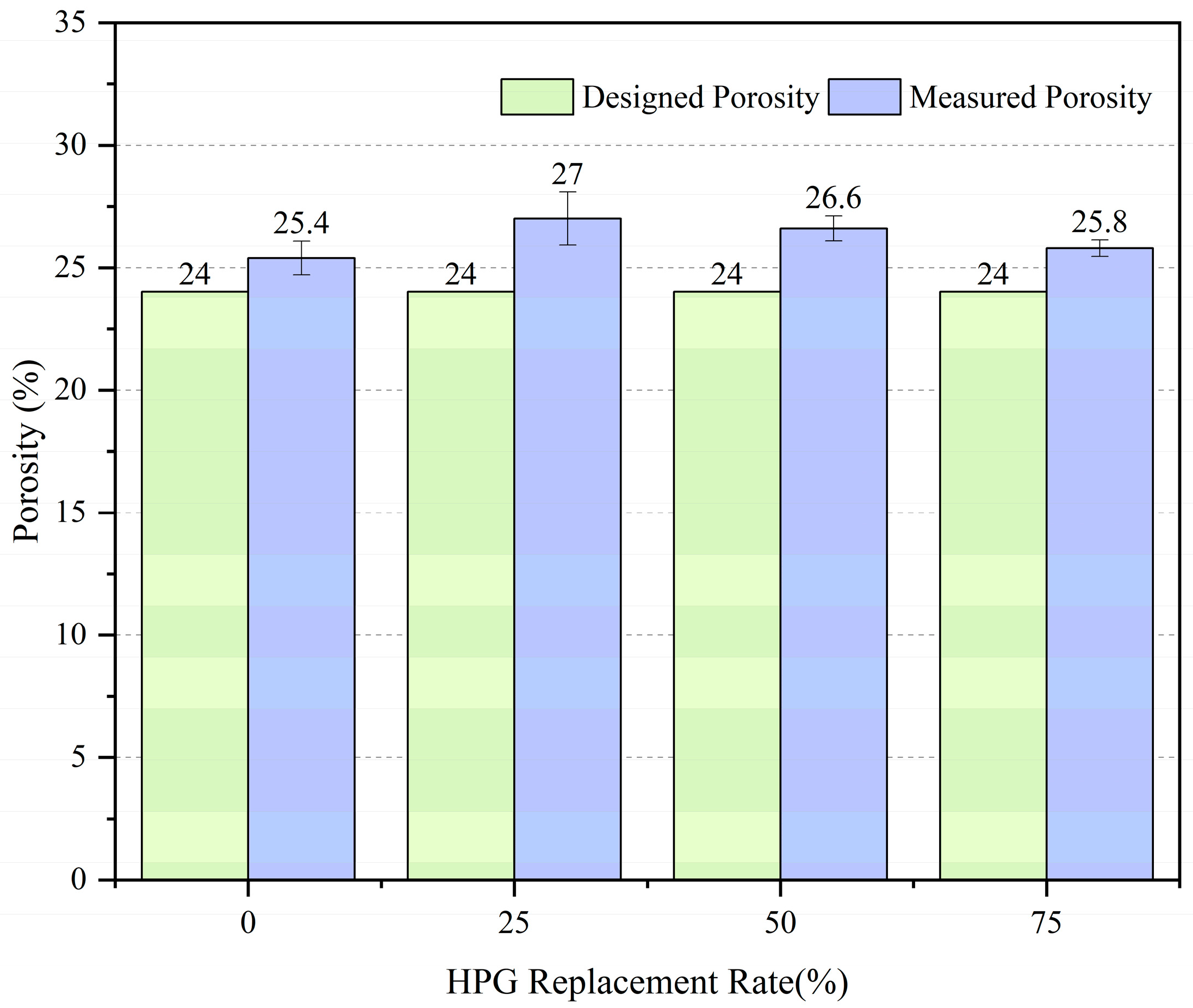

2.3.4. Porosity Test

- L0: Volume of the concrete cube specimen (mm3; the specimen used in this study was a cube with a side length of 100 mm);

- L1: Volume of drained water (mm3).

2.3.5. Microscopic Test

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Setting Time of Vegetation Concrete

3.1.1. Effect of HPG Replacement Rate on Setting Time (Group A)

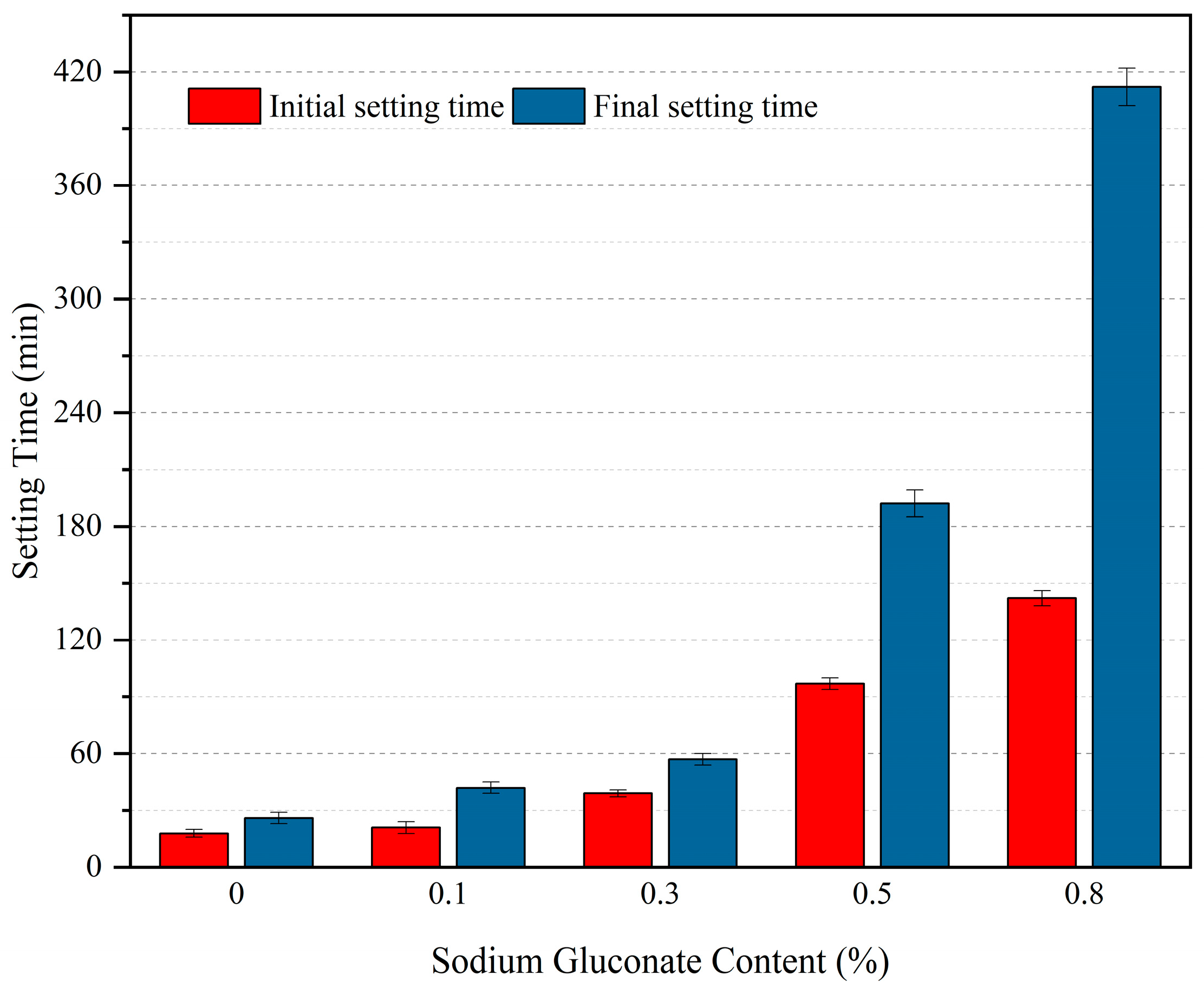

3.1.2. Effect of Sodium Gluconate Dosage on Setting Time (Group B)

3.2. Compressive Strength of Vegetation Concrete

3.2.1. Effect of HPG Replacement Rate on Compressive Strength

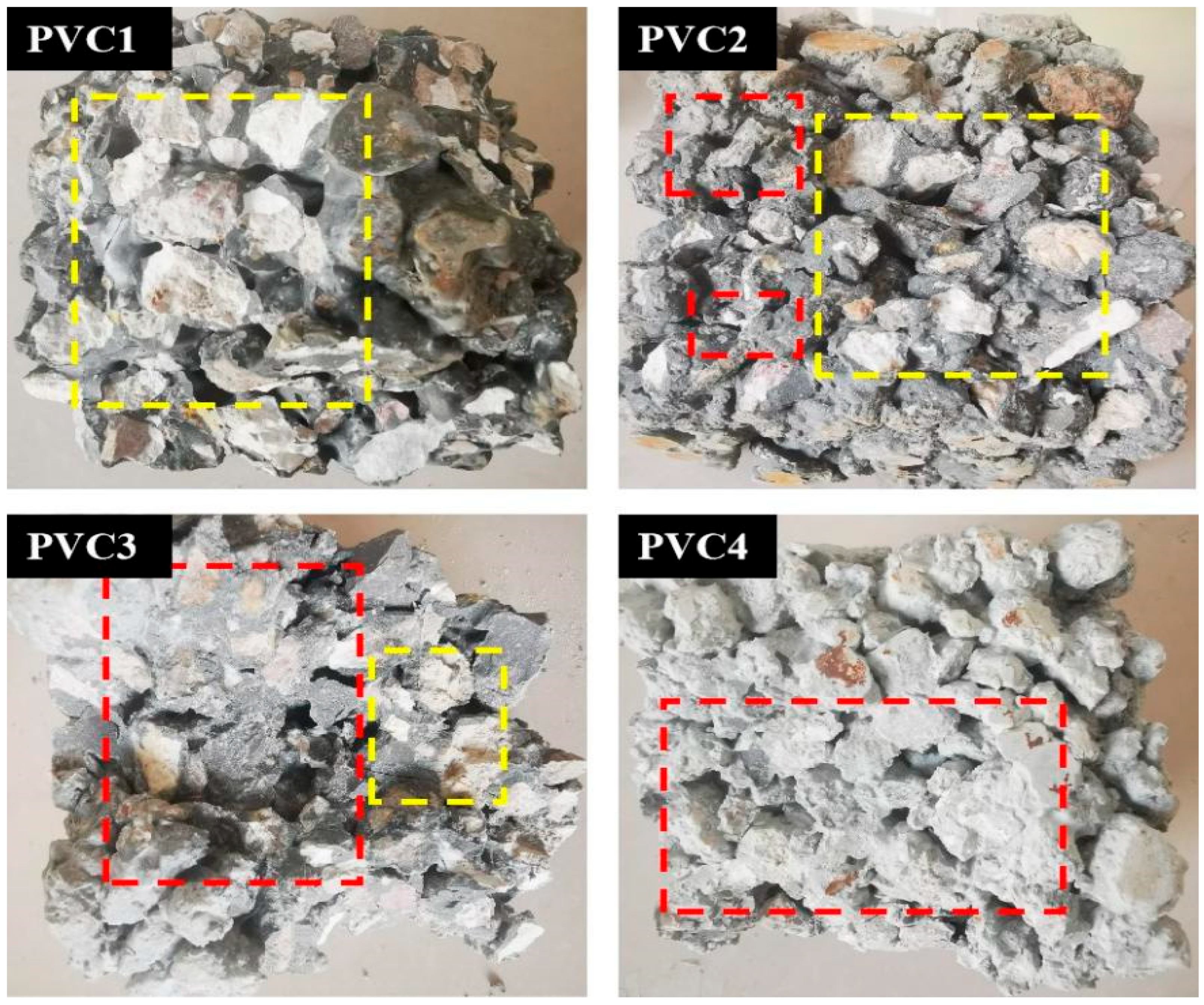

3.2.2. Fracture Surface Analysis of Vegetation Concrete

3.2.3. Effect of Sodium Gluconate on Compressive Strength

3.3. Alkalinity of Vegetation Concrete

- Early stage (3 d): Low pH value. HPG hydration dominates, while cement hydration is inhibited (resulting in less OH− generation). Additionally, a small amount of acidic substances in HPG react with Ca(OH)2 (a cement hydration product), consuming part of the OH−.

- Mid-stage (14 d): pH value reaches the peak. Cement hydration is enhanced, and the generation of Ca(OH)2 exceeds its consumption, leading to the accumulation of OH−.

- Late stage (28 d): pH value slightly decreases and stabilizes. This may be due to weakened cement hydration or the secondary hydration reaction between the silica fume (an alkali-active material) and Ca(OH)2 (resulting in higher OH− consumption than generation).

3.4. Porosity of Vegetation Concrete

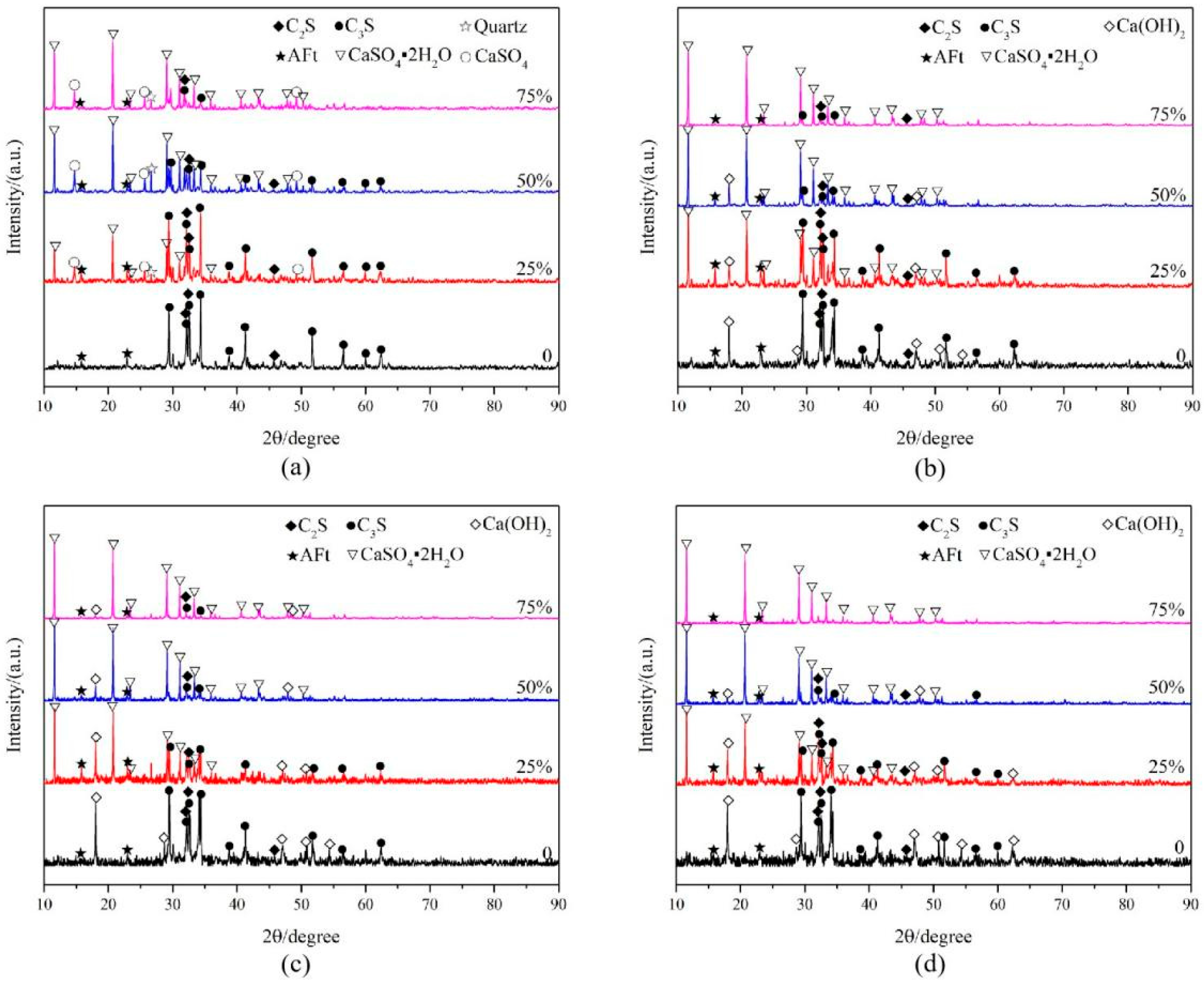

3.5. Analysis of Hydration Products

3.5.1. Hydration Products at Early Age (3 d)

3.5.2. Hydration Products at Mid–Late Age (7 d–28 d)

3.5.3. C-S-H (Main Source of Later-Stage Strength)

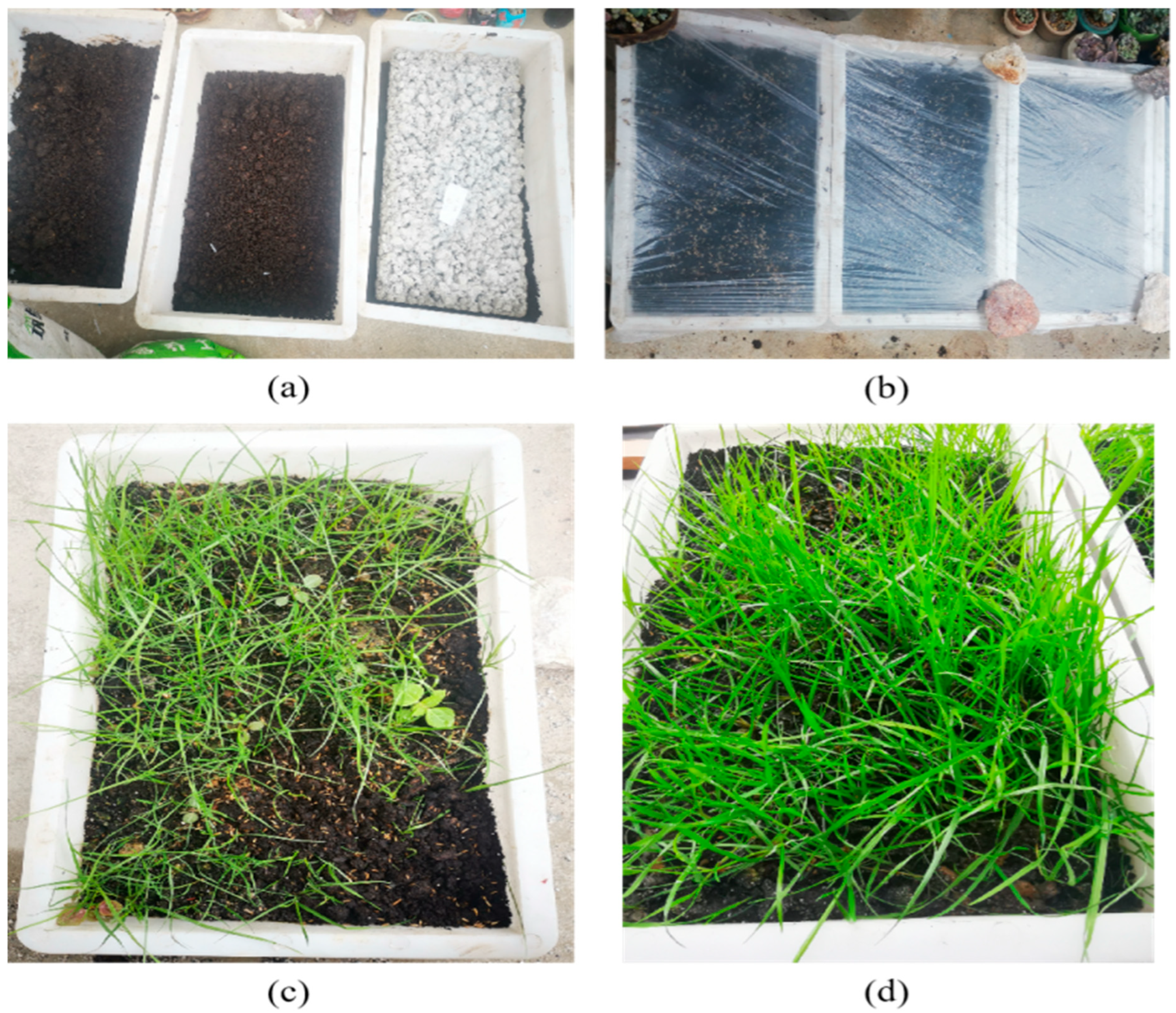

3.6. Growth Performance of Plants

4. Conclusions

- For vegetation concrete using HPG to replace cement (as cementitious material) and recycled aggregates to replace natural crushed stone (as coarse aggregates): With increases in HPG replacement rate, the compressive strength gradually decreases, but the alkali-regulating effect is significant. When the porosity is 24% and the HPG content is 50%, the vegetation concrete exhibits optimal performance: the 28-day compressive strength reaches 12.3 MPa, and the pH value is 9.7 (19.8% lower than that of the 0% HPG group). Notably, compared with existing studies where the phosphogypsum content is typically 20%, this study increases the HPG content to 50% while maintaining a compressive strength exceeding 10 MPa and incorporating recycled aggregates. These results demonstrate that the proposed vegetation concrete possesses favorable mechanical properties and a suitable alkaline environment for plant growth.

- When recycled aggregates are used as coarse aggregates: With increases in HPG replacement rate, the impact of recycled aggregates on the strength of vegetation concrete decreases. When the HPG replacement rate <50%, concrete damage is mainly manifested as recycled aggregate fracture, and concrete strength can be improved by enhancing aggregate strength. When the HPG replacement rate >50%, concrete damage is mainly manifested as paste fracture, and recycled aggregates are more suitable than natural crushed stone.

- The addition of sodium gluconate can effectively control the “flash set” of HPG, but has a significant impact on the early hydration of cement. When the HPG content is 50%, adding 0.5% sodium gluconate as a retarder results in an initial setting time of 97 min and a final setting time of 192 min, which meets construction requirements with little influence on later-stage strength. Microscopic analysis shows that the early strength (3 d–7 d) of vegetation concrete is mainly contributed by CaSO4·2H2O crystals (HPG hydration product), while the later-stage strength is supplemented by C-S-H (cement hydration product). Additionally, C2S and C3S mineral phases exist in the system, which have potential for further hydration.

- Planting tests show that when the porosity is 24% and the HPG content is 50%, Tall fescue forms a lawn within 30 days; at 60 days, the plant height is 18 cm and the root length is 6–8 cm. Some roots grow along the sidewalls of concrete pores and penetrate the 5 cm thick vegetation concrete slab, with no lodging or yellowing, demonstrating good growth status.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, C.; Xia, Y.Y.; Chen, J.G.; Huang, K.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.J.; Huang, Z.J.; Wang, X.H.; Rao, C.; Shi, M.S. Research and application progress of vegetation porous concrete. Materials 2023, 16, 7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Song, Z.; Ma, L. Experimental study on vegetation technology and anti-erosion effect of highway ecological slope. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. 2023, 40, 82–89. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nan, S.; Cheng, X.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, N.; Wang, P. Research on alkali reduction technology of solid waste ecological concrete. J. Qingdao Univ. Technol. 2024, 45, 74–80. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Jia, Y.H.; Yuan, L.J.; Qiu, J.; Xie, C. Experimental study on the vegetation characteristics of biochar-modified vegetation concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 206, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; Mao, J. Effects of concrete content on seed germination and seeding establishment in vegetation concrete matrix in slope restoration. Ecol. Eng. 2013, 58, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. Study on planting structure of vegetation concrete and preparation of nutrient soil. Concrete 2012, 11, 124–127. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Xu, G.; Lü, X. Experimental study on eco-environmental effect of porous concrete. J. Southeast Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2008, 38, 794–798. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Provis, J.L.; Bernal, S.A. Geopolymers and related alkali-related materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2014, 44, 299–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y. Study on initial compressive strength characteristics of vegetation concrete based on 28-day age. Water Power 2023, 49, 106–110. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W.C.; Mohseni, E.; Wang, Z.Y. Development of vegetation concrete technology for slope protection and greening. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 179, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L. Experimental study on properties of low-alkali vegetation concrete. Guangxi Water Resour. Hydropower 2024, 6, 5–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Z.K.; Yan, Y.; Huang, B.Y.; Xie, Y.X. Performance of Ecological Pervious Concrete Prepared with Sandstone/Limestone-Mixed Aggregates. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2023, 2023, 7114380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K. Preparation and performance test of vegetation concrete with high volume fly ash. Concrete 2016, 3, 151–154. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Q.; Zhou, J.; Xu, W.; Yuan, X. Study on the preparation and properties of vegetation lightweight porous concrete. Materials 2024, 17, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Gao, H.; Meng, X. Physical and mechanical properties of novel porous ecological concrete based on magnesium phosphate cement. Materials 2022, 15, 7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H.; Kim, C.S.; Jeon, J.H.; Park, C.G. Effects on the physical and mechanical properties of porous concrete for plant growth of blast furnace slag, natural jute fiber, and styrene butadiene latex using a dry mixing manufacturing process. Materials 2016, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, G.P.; Kaliyappan, S.P.; Ramamoorthy, V.L.; Shanmugam, S.; AlObaid, A.; Warad, I.; Velusamy, S.; Achuthan, A.; Sundaram, H.; Vinayagam, M.; et al. Low alkaline vegetation concrete with silica fume and nano-fly ash composites to improve the planting properties and soil ecology. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2024, 13, 20230201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Gao, W.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, K. Optimization study on alkali reduction and vegetation technology of vegetation concrete. J. Shandong Agric. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 48, 429–432. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wei, W.; Xu, Y.; Shen, C. Study on alkali reduction effect of silane impregnation on large-pore ecological concrete. Concrete 2019, 3, 157–160. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Su, L.; Xiao, H.; Xu, W.; Yan, W.M.; Xia, Z. Preparation of shale ceramsite vegetative porous concrete and its performance as a planting medium. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2021, 25, 2111–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Lu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, P.; Gu, J. Harmless disposal of phosphogypsum synergized red mud: Harmful element control and material utilization. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Bai, H.; Gao, Y.; Xiu, X. Current status and 14th Five-Year development trend of comprehensive utilization of phosphogypsum. Inorg. Chem. Ind. 2022, 54, 1–4. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lin, R.S.; Huang, G.; Ma, F.Y.; Pan, T.H.; Wang, X.Y.; Han, Y.; Liao, Y.P. Investigation of phosphogypsum-based cementitious materials: The effect of lime modification. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 18, 100477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, K.; Chen, B.; Pan, Y. Utilization of untreated-phosphogypsum as filling and binding material in preparing grouting materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 265, 120749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Li, X.; Yu, J.-X.; Li, F.; Guo, L.; Song, G.; Xiao, C.; Zhou, F.; Chi, R.; Feng, G. Highly efficient recovery of phosphate and fluoride from phosphogypsum leachate: Selective precipitation and adsorption. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 367, 122064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Gao, J.; Zhao, Y. Investigation on the hydration of hemihydrate phosphogypsum after post treatment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 229, 116864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Q. Study on Properties and Durability of β-Hemihydrate Phosphogypsum-Based Cementitious Materials. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing Jiaotong University, Chongqing, China, 2024. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Fang, Y.; Wei, P.; Zeng, H.; Shen, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Chu, H. Optimization study on alkali-reduction techniques and vegetation performance of planting concrete incorporating phosphogypsum. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 482, 141663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, J.; Chu, H.; Zeng, H.; Wei, P.; Dou, Z.; Jiang, L. Exploiting phosphogypsum as a by-product in porous vegetation concrete for riparian slope stabilisation and green-growing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 493, 143085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Liu, C.; Du, J.; Wang, C.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, X. Preparation of phosphogypsum ecological concrete and study on its phytogenic properties. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 12, 1539964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Liu, J.; Sun, Z.; Li, F. Effects of phosphogypsum and calcined phosphogypsum content on the basic physical and mechanical properties of Portland cement mortar. J. Test. Eval. 2020, 48, 3539–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.S.; Singh, S.K. Use of indigenous sources of sulphur in soils of eastern India for higher crops yield and quality—A review. Agric. Rev. 2016, 37, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CJJ/T134-2019; Technical Standard for the Treatment of Construction and Demolition Waste. China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Xu, K.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L. Compressive strength and prediction model establishment of recycled concrete mixed with different sources of coarse aggregates. Mater. Rep. 2025, 39, 90–98. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.Z. Recycled Aggregate Concrete Structures; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 251–297. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, S.; Kumar, S.; Baraie, S.K.V. Multi-scale characterisation of recycled aggregate concrete and prediction of its performance. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 106, 103480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabiec, A.M.; Zawal, D.; Rasaq, W.A. The effect of curing conditions on selected properties of recycled aggregate concrete. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Gholampour, A.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Toward the development of sustainable concretes with recycled concrete aggregates: Comprehensive review of studies on mechanical properties. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04018211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.Y.; Lehman, D.E.; Geng, Y.; Kuder, K. Time-dependent drying shrinkage model for concrete with coarse and fine recycled aggregate. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 105, 103426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shen, Y.; Liu, J.; Luo, K. Effects of different retarders on setting time and hardening properties of hemihydrate phosphogypsum. Mater. Rep. 2022, 36, 262–266. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Xu, R.; Mao, R. Experimental study on adaptability between polycarboxylate superplasticizer and building gypsum. In Proceedings of the 6th Annual Conference of Gypsum Building Materials Branch of China Building Materials Federation & 10th National Gypsum Technology Exchange Conference and Exhibition, Suzhou, Chian, 25–27 November 2015; Suzhou Xingbang Chemical Building Materials Co., Ltd.: Suzhou, China, 2015; pp. 98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Li, H. Experimental study on mix ratio design of no-fines concrete. Yangtze River 2021, 52, 175–180+194. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Li, Z.; Li, R.; Jiang, S. Study on the influence of basic properties of recycled vegetation concrete. Concrete 2023, 4, 55–58+63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, P.; Yan, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, J. Study on the performance optimization of plant-growing ecological concrete. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yin, J.; Li, S. Gradation characteristic analysis of vegetation-type porous concrete. Mater. Und Werkst. 2019, 50, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Su, R.; Qiao, H. Study on physical and vegetation properties of vegetation concrete. Concrete 2025, 5, 191–195+200. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Yi, S.; Xu, X.; Yao, J. New insights into impacts of pre-wetting strategies of recycled coarse aggregate (RCA) on microstructure and performance of concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 99, 111525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Shen, C.; Ye, M.; Huang, S.; He, J.; Cui, D. Influencing factors of porosity and strength of plant-growing concrete. Materials 2023, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard for Test Methods of Physical and Mechanical Properties of Concrete. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2019.

- GB/T 1346-2011; Standard Test Methods for Water Requirement of Normal Consistency, Setting Time and Soundness of Cement. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2011.

- Peng, L. Study on Construction Technology and Component Design of Vegetation Concrete. Master’s Thesis, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, China, 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; He, G.; Xue, G. Review of test methods for alkaline environment in vegetation concrete. In Proceedings of the 4th National Special Concrete Technology Academic Exchange Conference & 2013 Annual Meeting of Concrete Quality Professional Committee of China Civil Engineering Society, Beijing, China, 23–25 October 2013; China Academy of Building Research Institute of Building Materials: Beijing, China, 2013. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.C.; Sun, C.; Ding, X.Q.; Kang, T.B.; Nie, X.M. Experimental study on the vegetation growing recycled concrete and synergistic effect with plant roots. Materials 2019, 12, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Q.; Hao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Du, S.; Jiang, L. Effects of anions and pH value in industrial by-product gypsum on cement properties. Non-Met. Mines 2025, 48, 47–50+55. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z.; Li, J.; Song, L. Study on dehydration and setting-hardening properties of phosphogypsum. J. Harbin Univ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 3, 48–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. Study on Preparation, Properties and Frost Resistance of Porous Concrete for Plant Growth. Master’s Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2006. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

| Component (Mass %) | Setting Time (min) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaO | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | SO3 | MgO | Initial Setting | Final Setting | |

| 63.2 | 21.5 | 5.4 | 3.8 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 185 | 245 | 45.5 |

| Component (Mass %) | Setting Time (min) | Dry Strength (MPa) | pH | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MgO | Na2O | P2O5 | F | CaSO4·2H2O | CaSO4·0.5H2O | CaSO4 | Initial Setting | Final Setting | ||

| 0.014 | 0.006 | 0.072 | 0.041 | 5.1 | 84.97 | 1.8 | 5 | 11 | 12.8 | 3.8 |

| Gradation/mm | Apparent Density/(kg/m3) | Bulk Density/(kg/m3) | Water Absorption Rate/% | Crushing Value/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10–20 | 2556 | 1327 | 4.1 | 15.6 |

| Mix Group | No. | HPG Replacement Rate (%) | RCA(kg/m3) | HPG(kg/m3) | OPC(kg/m3) | SF(kg/m3) | SG (%) | PCE (%) | W/B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | PVC1 | 0 | 1300 | 0 | 458 | 24 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.24 |

| PVC2 | 25 | 1300 | 115 | 343 | 24 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.27 | |

| PVC3 | 50 | 1300 | 229 | 229 | 24 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.30 | |

| PVC4 | 75 | 1300 | 343 | 115 | 24 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.33 | |

| Group B | PVC5 | 50 | 1300 | 229 | 229 | 24 | 0 | 1 | 0.30 |

| PVC6 | 50 | 1300 | 229 | 229 | 24 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.30 | |

| PVC7 | 50 | 1300 | 229 | 229 | 24 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.30 | |

| PVC8 | 50 | 1300 | 229 | 229 | 24 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.30 | |

| PVC9 | 50 | 1300 | 229 | 229 | 24 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xiao, Z.; Deng, N.; Shen, M.; Wang, T.; Chen, X.; Li, S. Effects of Phosphogypsum–Recycled Aggregate Solid Waste Base on Properties of Vegetation Concrete. Materials 2026, 19, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010014

Xiao Z, Deng N, Shen M, Wang T, Chen X, Li S. Effects of Phosphogypsum–Recycled Aggregate Solid Waste Base on Properties of Vegetation Concrete. Materials. 2026; 19(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Zhan, Nianchun Deng, Mingxuan Shen, Tianlong Wang, Xiaobing Chen, and Shuangcan Li. 2026. "Effects of Phosphogypsum–Recycled Aggregate Solid Waste Base on Properties of Vegetation Concrete" Materials 19, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010014

APA StyleXiao, Z., Deng, N., Shen, M., Wang, T., Chen, X., & Li, S. (2026). Effects of Phosphogypsum–Recycled Aggregate Solid Waste Base on Properties of Vegetation Concrete. Materials, 19(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010014