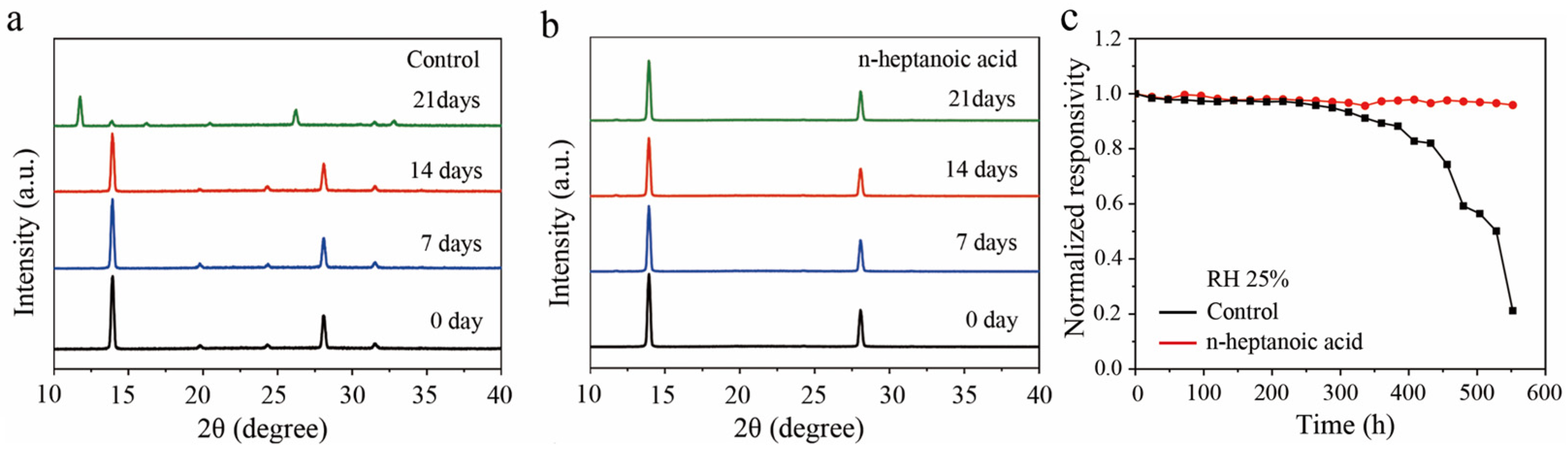

Enhanced Stability and Performance of α-FAPbI3 Photodetectors via Long-Chain n-Heptanoic Acid Passivation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Device Fabrication

2.3. Characterization

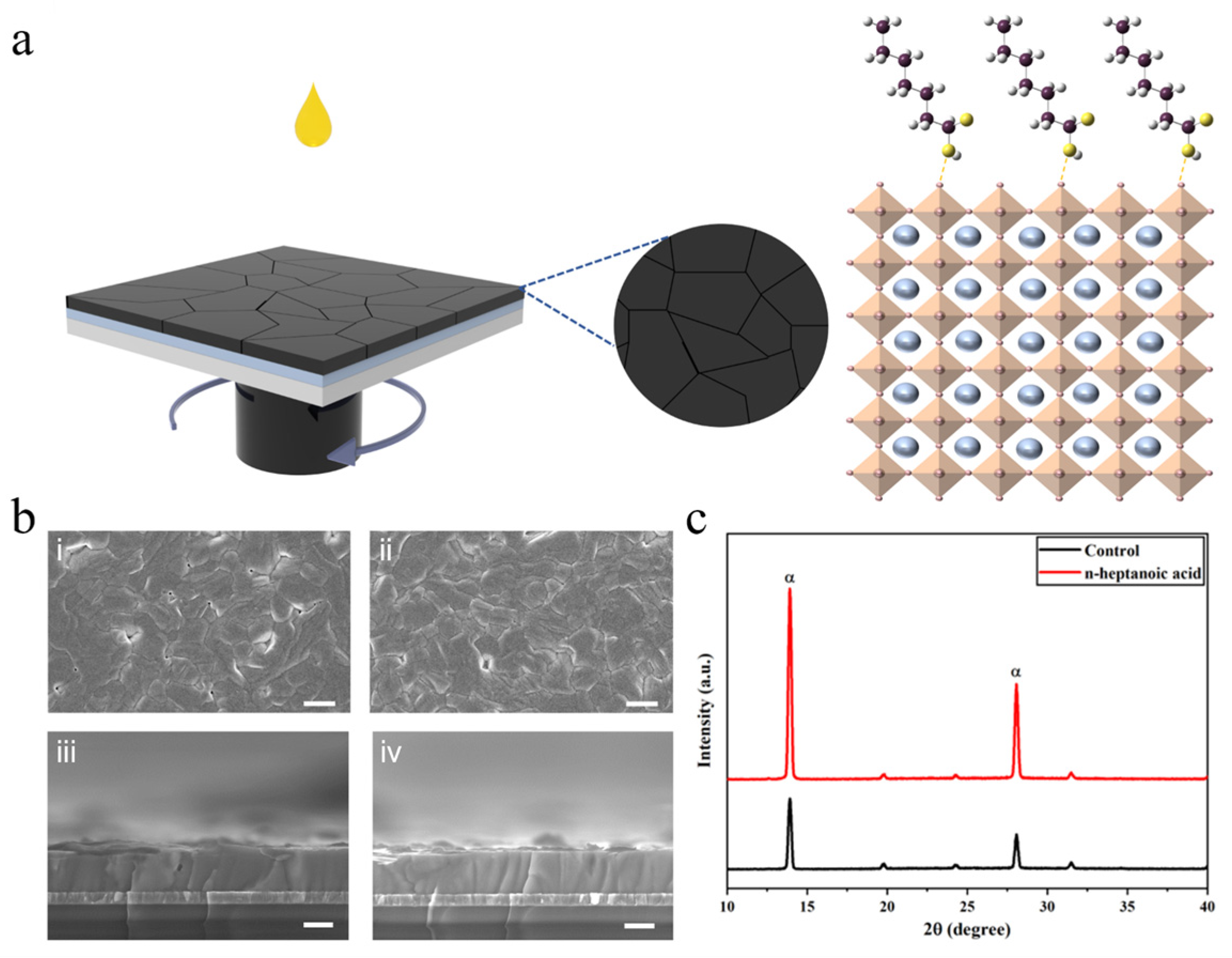

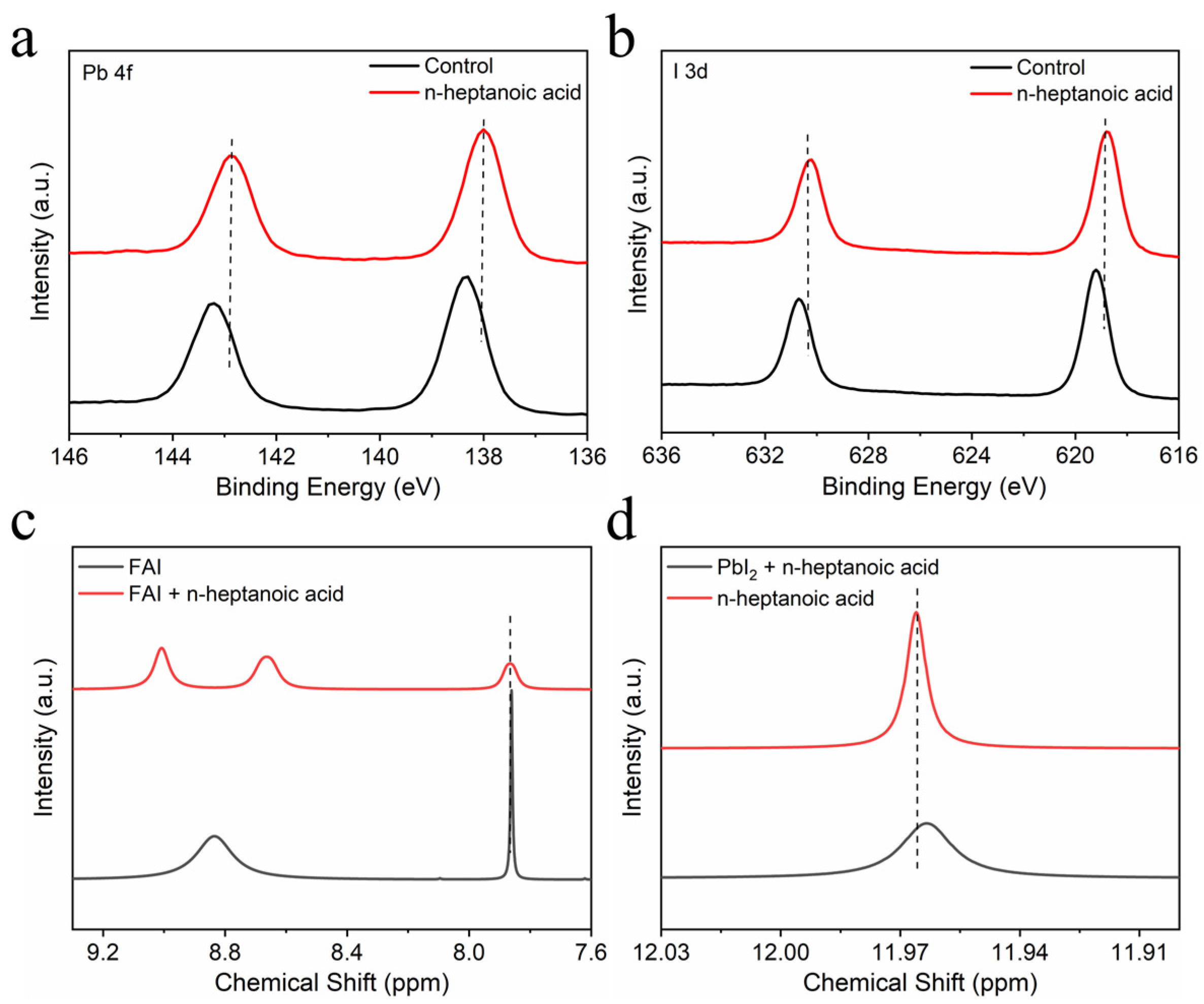

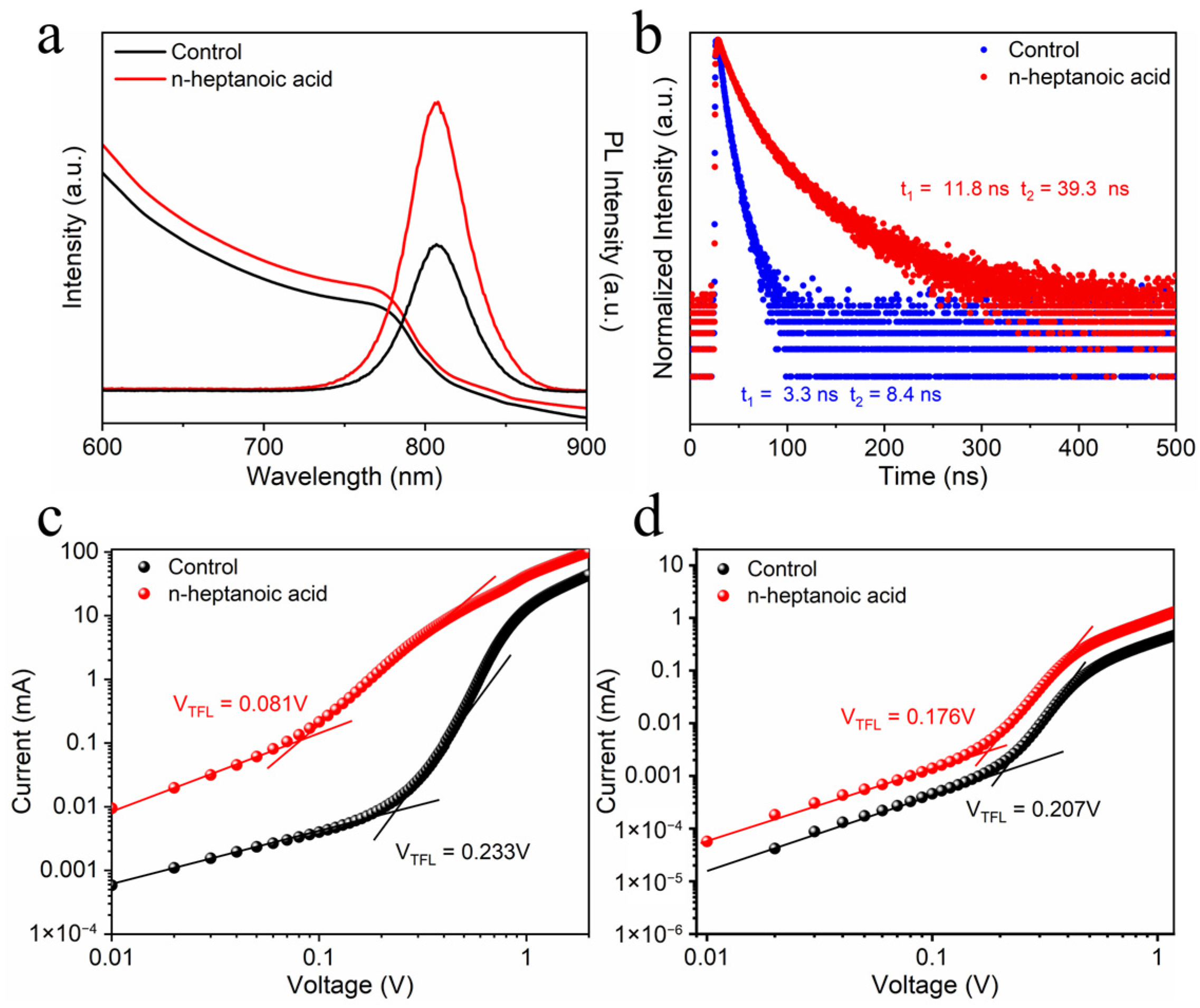

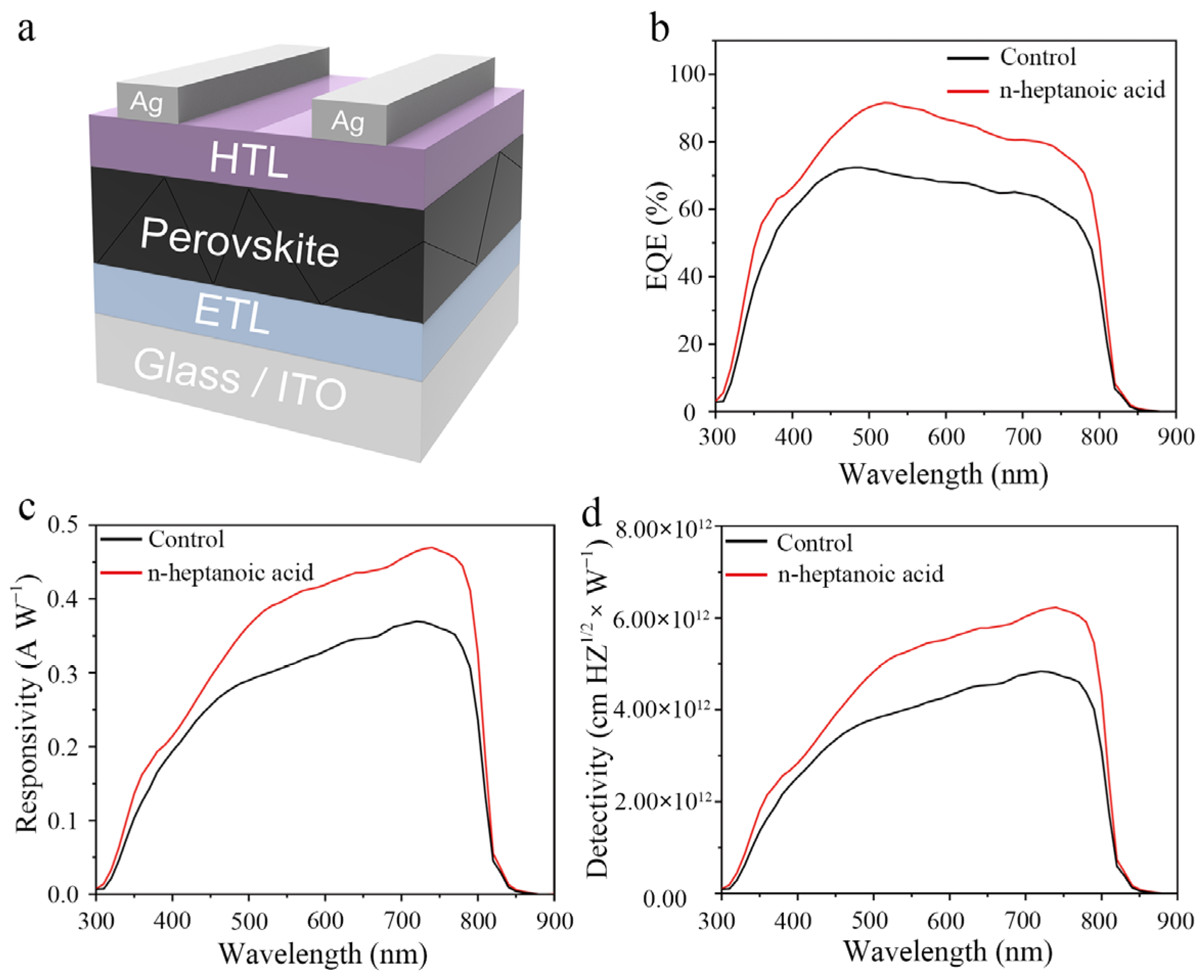

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, Y.; Noh, H.; Paulsen, B.D.; Kim, J.; Jo, I.-Y.; Ahn, H.; Rivnay, J.; Yoon, M.-H. Strain-Engineering Induced Anisotropic Crystallite Orientation and Maximized Carrier Mobility for High-Performance Microfiber-Based Organic Bioelectronic Devices. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2007550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccherozzi, F.; Ghidini, M.; Vickers, M.; Moya, X.; Cavill, S.A.; Elnaggar, H.; Lamirand, A.D.; Mathur, N.D.; Dhesi, S.S. Inverted shear-strain magnetoelastic coupling at the Fe/BaTiO3 interface from polarised X-ray imaging. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafi, A.M.; Uddin, M.G.; Cui, X.; Ali, F.; Ahmed, F.; Radwan, M.; Das, S.; Mehmood, N.; Sun, Z.; Lipsanen, H. Strain Engineering for Enhancing Carrier Mobility in MoTe2 Field-Effect Transistors. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2303437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Xie, D.; Ren, T. Probing the Strain Direction-Dependent Nonmonotonic Optical Bandgap Modulation of Layered Violet Phosphorus. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2305770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, G.; Zhang, K.; Liu, X. Performance and mechanism of tetracycline removal by peroxymonosulfate-assisted double Z-scheme LaFeO3/g-C3N4/ZnO heterojunction under visible light drive. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 39, 104302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, T.; Jia, L.; Feng, J.; Yang, S.; Ding, J.; Liu, S.; Fang, Z. Advances in Single-Halogen Wide-Bandgap Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2416264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Calderon, A.D.; Fang, Q.; Liu, X. Data-Driven Optimization and Mechanical Assessment of Perovskite Solar Cells via Stacking Ensemble and SHAP Interpretability. Materials 2025, 18, 4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Zhang, F. Advancing Flexible Perovskite Solar Cells from Lab to Commercialization: Materials and Deposition Strategies. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2507644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Xing, J.; Huang, X.; Sun, Y.; Ma, X.; Huang, Z.; Wang, B.; Jiang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wan, L.; et al. Controllable Efficient 3D/2D Perovskite Polycrystalline Heterojunction for Record-Performance Mixed-Cation Horizontal Photodetector. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2504352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotelo-Lerma, M.; Fernandez-Izquierdo, L.; Ruiz-Molina, M.A.; Borges-Doren, I.; Haroldson, R.; Quevedo-Lopez, M. CsPbBr3 and Cs2AgBiBr6 Composite Thick Films with Potential Photodetector Applications. Materials 2024, 17, 5123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Hu, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhang, S.; Su, J.; Guo, X.; Xiao, J.; Lin, Z.; Hao, Y.; Chang, J. Solution-Processed Mixed Halide Wide-Bandgap Perovskite CsPb(Cl1−xFx)3 for Ultrafast Self-Powered Ultraviolet Photodetector. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e16978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, Y.; Yao, J.; Song, J. Cation-Anion-Pair-Assisted Synthesis Strategy Enables High-Performance Pure Blue Perovskite Quantum Dot-Based Light-Emitting Diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e20569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yan, C.; Zhao, H.; Yin, C.; Bai, S. Modulations of Quasi-Two-Dimensional Metal Halide Perovskites toward High-Performance Blue Light-Emitting Diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 2509226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Ge, C.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, X.; Luo, J.; Tang, J. Efficient Pure-Red Tin-Based Perovskite Light-Emitting Diodes Enabled by Multifunctional Lewis-Base Additives. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2506504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Feeney, T.; Roger, J.; Gholipoor, M.; Hu, H.; Zhao, D.; Howard, I.; Deschler, F.; Lemmer, U.; et al. Electrically-Switchable Gain in Optically Pumped CsPbBr3 Lasers with Low Threshold at Nanosecond Pumping. Small 2025, 21, 2411935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Ren, J.; Yang, D.; Li, L.; Guo, L.; Wang, S.; Yang, Z. Rare Earth Ion-Doped Metal Halide Perovskite Miro-Nano Single Crystals for Low Threshold Perovskite Lasers. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2025, 13, e01595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, A.M.; Vaitkevičius, A.; Stanionytė, S.; Miasojedovas, S.; Kreiza, G.; Ščajev, P. Highly Stable Solution-Processed CsZnPbI3 Perovskite Distributed Feedback Lasers. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2025, 13, e01896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Yao, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, B.; Ji, C.; Sun, Z.; Hong, M.; Luo, J. Highly Oriented Thin Films of 2D Ruddlesden-Popper Hybrid Perovskite toward Superfast Response Photodetectors. Small 2019, 15, 1901194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Bao, H.; Xu, J.; Zhang, G.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Qin, C.; et al. Buried Grating Enables Fast Response Self-Powered Polarization-Sensitive Perovskite Photodetectors for High-Speed Optical Communication and Polarization Imaging. Small 2025, 21, 2411610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Wang, L.; Feng, A.; Yang, S.; Li, N.; Jiang, X.; Liu, N.; Xie, S.; Guo, X.; Fang, Y.; et al. Self-Powered FA0.55MA0.45PbI3 Single-Crystal Perovskite X-Ray Detectors with High Sensitivity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2109149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhou, B.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Chu, Y.; Huang, J. Distinguishable Detection of Ultraviolet, Visible, and Infrared Spectrum with High-Responsivity Perovskite-Based Flexible Photosensors. Small 2018, 14, 1800527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, F.; Fu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lin, X.; Hu, Z.; Du, H.; et al. Developing Oxygen Vacancy Rich Perovskite for Broad-Spectrum-Responsive Photothermal Assisted Photocatalytic Dehydrogenation of MgH2. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 15, e04765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.-X.; Wang, J.-Z.; Zhang, Z.-X.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Gao, Y.; Luo, L.-B. Broadband, Ultrafast, Self-Driven Photodetector Based on Cs-Doped FAPbI3 Perovskite Thin Film. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2017, 5, 1700654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Wang, Y.; Khan, Q.U.; Li, X.; Deng, L.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Yue, X.; et al. Intermediate Phase Free α-FAPbI3 Perovskite via Green Solvent Assisted Perovskite Single Crystal Redissolution Strategy. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2302298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Hu, Y.; Lou, Z.; Hou, Y.; Teng, F. High-Performance Photodiode-Type Photodetectors Based on Polycrystalline Formamidinium Lead Iodide Perovskite Thin Films. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Yue, Z.; Ye, Z.; Li, H.; Luo, H.; Yang, Q.-D.; Zhou, Y.; Huo, Y.; Cheng, Y. Improving the Efficiency and Stability of MAPbI3 Perovskite Solar Cells by Dipeptide Molecules. Small 2024, 20, 2311400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Li, Y.; Hou, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W. 4,4′-Sulfonyldibenzoic Acid as a Dual-Functional Additive for Defect Passivation and Crystallization Promotion of MAPbI3 Toward High-Performance Perovskite Photodetectors. J. Phys. Chem. C 2025, 129, 20824–20832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Li, X.; Wan, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Bao, Q.; Fang, J. Efficient Passivation with Lead Pyridine-2-Carboxylic for High-Performance and Stable Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1901852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Huang, X.; Ma, C.; Xue, J.; Li, Y.; Kim, D.; Yang, H.-S.; Zhang, Y.; Lee, B.R.; Kim, J.; et al. Tailoring the Interface with a Multifunctional Ligand for Highly Efficient and Stable FAPbI3 Perovskite Solar Cells and Modules. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2301603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Yang, H.; Yan, H.; Sun, X.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y. Multifunctional Ionic Liquid Assisted Crystallization Regulation and In Situ Defect Passivation for High-Performance Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e19195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Liu, X.; Liu, G.; Yang, G.; Fang, Y.; Shen, J.; Jin, B.; Chen, X.; Huang, Y.-H.; Wang, X.-D.; et al. Blade-Coating (100)-Oriented α-FAPbI3 Perovskite Films via Crystal Surface Energy Regulation for Efficient and Stable Inverted Perovskite Photovoltaics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202403196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Liu, Y.; Pu, W.; Li, Y.; Yue, H.; Zhang, M.; Tian, J. Gel-Derived Amorphous Precursor Enables Homogeneous Pure-Phase α-FAPbI3 Films for Efficient and Stable Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2400467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Tan, C.; Du, X.; Tian, F.; Shi, J.; Wu, H.; Luo, Y.; Li, D.; et al. Synergistically Regulating CBD-SnO2/Perovskite Buried Interface for Efficient FAPbI3 Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2404173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Li, W.; Feng, X.; He, Y.; Pan, W.; Guo, K.; Li, M.; Tan, M.; Yang, B.; Wei, H. Low-Temperature Crystallized and Flexible 1D/3D Perovskite Heterostructure with Robust Flexibility and High EQE-Bandwidth Product. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2213955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Han, S.G.; Sung, W.; Kim, S.; Min, J.; Kim, M.K.; Choi, W.; Lee, H.; Lee, D.; Kim, M.; et al. Photomultiplication-Type Organic Photodetectors with High EQE-Bandwidth Product by Introducing a Perovskite Quantum Dot Interlayer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2300695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfo, T.A.; Yıldız, D.E.; Hussaini, A.A.; Yıldırım, M.; Gündüz, B. The light detection performance of the Al/DCJTB/n-Si Schottky type photodetector for a wide-range spectrum. Opt. Mater. 2026, 169, 117688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bai, X.; Lou, Y.; Wang, M.; Gu, Z.; Song, Y. Enhanced Stability and Performance of α-FAPbI3 Photodetectors via Long-Chain n-Heptanoic Acid Passivation. Materials 2026, 19, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010122

Bai X, Lou Y, Wang M, Gu Z, Song Y. Enhanced Stability and Performance of α-FAPbI3 Photodetectors via Long-Chain n-Heptanoic Acid Passivation. Materials. 2026; 19(1):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010122

Chicago/Turabian StyleBai, Xintao, Yunjie Lou, Mengxuan Wang, Zhenkun Gu, and Yanlin Song. 2026. "Enhanced Stability and Performance of α-FAPbI3 Photodetectors via Long-Chain n-Heptanoic Acid Passivation" Materials 19, no. 1: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010122

APA StyleBai, X., Lou, Y., Wang, M., Gu, Z., & Song, Y. (2026). Enhanced Stability and Performance of α-FAPbI3 Photodetectors via Long-Chain n-Heptanoic Acid Passivation. Materials, 19(1), 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010122