Studies on the Influence of Compaction Parameters on the Mechanical Properties of Oak Sawdust Briquettes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Multivariate Analysis of Density D

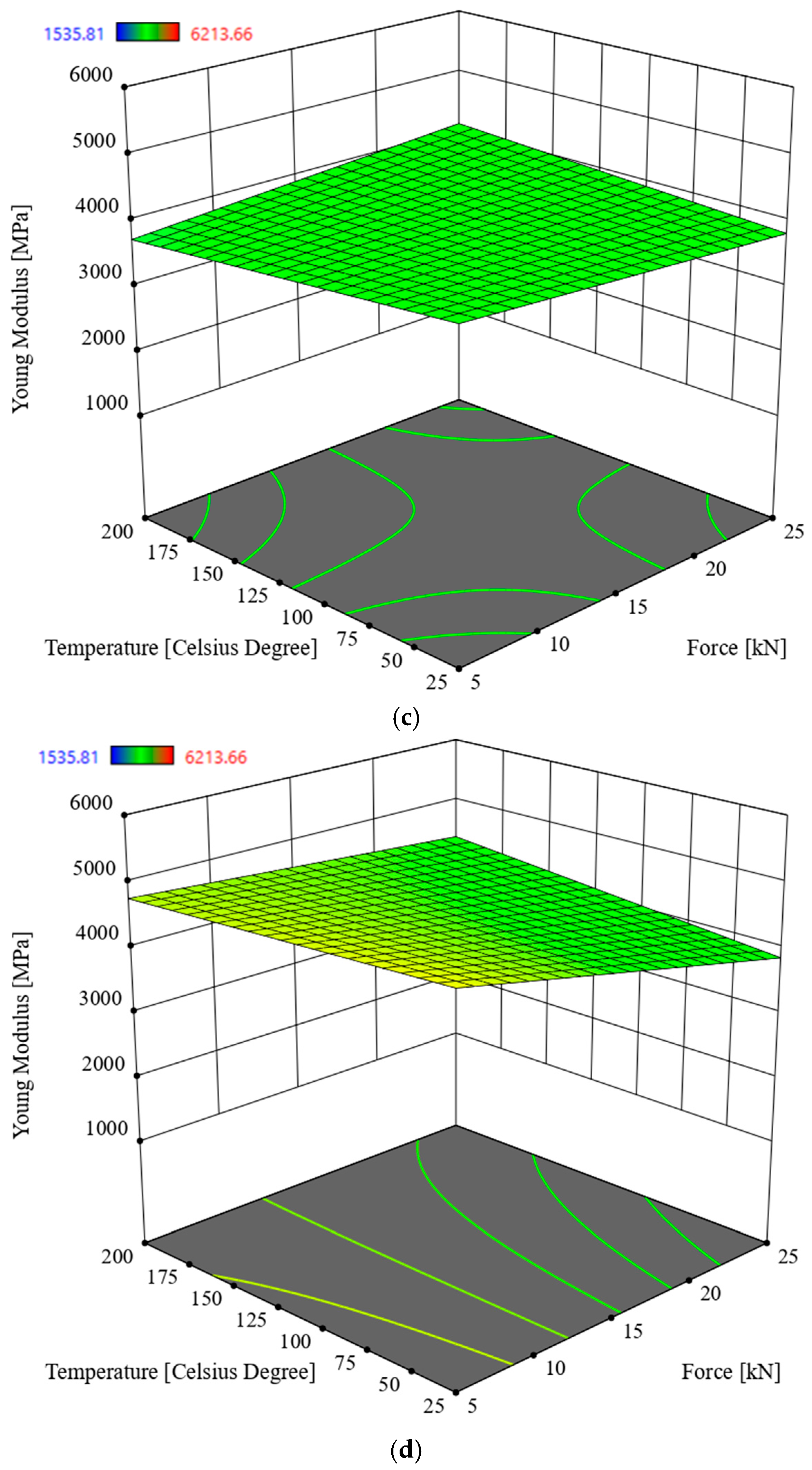

3.2. Multivariate Analysis of Young Modulus E

3.3. Optimization of the Selection of Compaction Process Parameters

4. Conclusions

- -

- for sawdust moisture content of 9%, the most significant influence on briquette density D is exerted by compaction force F, followed by temperature T and particle size S,

- -

- -

- for sawdust moisture content of 20%, the parameter in the form of compaction force F has a significant impact on briquette density, followed by moisture content, temperature, and particle size,

- -

- -

- analysis of variance (ANOVA) enabled the optimal selection of compaction process parameters, where the main criterion in general terms was to minimize the energy consumption of the compaction process,

- -

- -

- by foregoing sieving (i.e., further reducing the energy consumption of the process), we can obtain briquettes with a density D approximately 3% lower and a Young’s modulus E approximately 6% higher than that obtained from sawdust fractions with particle sizes S = 2.5–5 mm (this results by optimization was given where F = 5 kN, M = 20%, T = 25 °C, S > 5 mm, D = 840.4 kg/m3, E = 5016.6 MPa).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, W.S. Powering a safer future with novel energy solutions. Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull. 2025, 104, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Global Energy Review 2025; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2025.

- Mohsen, F.M.; Mjbel, H.M.; Challoob, A.F.; Alkhazaleh, R.; Alahmer, A. Advancements in green hydrogen production: A comprehensive review of prospects, challenges, and innovations in electrolyzer technologies. Fuel 2026, 404, 136251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seboka, A.D.; Morken, J.; Adaramola, M.S.; Ewunie, G.A.; Feng, L. Optimization of briquetting parameters and their effects on thermochemical fuel properties of biowaste briquettes. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2026, 404, 133277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyszomierski, R.; Bórawski, P.; Bełdycka-Bórawska, A. Competitive Potential of Plant Biomass in Poland Compared to Other Renewable Energy Sources for Heat and Electricity Production. Energies 2025, 18, 1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortadha, H.; Kerrouchi, H.B.; Al-Othman, A.; Tawalbeh, M. A Comprehensive Review of Biomass Pellets and Their Role in Sustainable Energy: Production, Properties, Environment, Economics, and Logistics. Waste Biomass Valorization 2025, 16, 4507–4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho Junior, L.M.; Diniz, F.F.; Martins, J.M.; Fuinhas, J.A.; Simoni, F.J.; Santos Júnior, E.P. Worldwide concentration of forest products for energy. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 77, 104331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aphraim, A.; Arlabosse, P.; Nzihou, P.; Minh, D.P.; Sharrock, P. Biomass categories. In Handbook on Characterization of Biomass, Biowaste and Related By-Products, 1st ed.; Nzihou, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Padder, A.S.; Khan, R.; Rather, R.A. Biofuel generations: New insights into challenges and opportunities in their microbe-derived industrial production. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 185, 107220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warguła, Ł.; Wilczyński, D.; Wieczorek, B.; Palander, T.; Gierz, Ł.; Nati, C.; Sydor, M. Characterizing Sawdust Fractional Composition from Oak Parquet Woodworking for Briquette and Pellet Production. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2023, 17, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibitoye, S.E.; Mahamood, R.M.; Jen, T.-C.; Loha, C.; Akinlabi, E.T. An overview of biomass solid fuels: Biomass sources, processing methods, and morphological and microstructural properties. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2023, 8, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumuluru, J.S.; Wright, C.T.; Hess, J.R.; Kenney, K.L. A review of biomass densification system to develop uniform feedstock commodities for bioenergy application. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2011, 5, 683–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, T.; Liu, T.; Cai, H. Parametric studies on energy utilization of the Chinese medicine residues: Preparation and properties of densified pellet. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala-Litwiniak, A.; Musiał, D.; Nabiałczyk, M. Computational and Experimental Studies on Combustion and Co-Combustion of Wood Pellets with Waste Glycerol. Materials 2023, 16, 7156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Su, Z.; Jiang, T. Improving the Properties of Magnetite Green Pellets with a Novel Organic Composite Binder. Materials 2022, 15, 6999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laosena, R.; Palamanit, A.; Luengchavanon, M.; Kittijaruwattana, J.; Nakason, C.; Lee, S.H.; Chotikhun, A. Characterization of Mixed Pellets Made from Rubberwood (Hevea brasiliensis) and Refuse-Derived Fuel (RDF) Waste as Pellet Fuel. Materials 2022, 15, 3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horabik, J.; Bańda, M.; Józefaciuk, G.; Adamczuk, A.; Polakowski, C.; Stasiak, M.; Parafiniuk, P.; Wiącek, J.; Kobyłka, R.; Molenda, M. Breakage Strength of Wood Sawdust Pellets: Measurements and Modelling. Materials 2021, 14, 3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styks, J.; Knapczyk, A.; Łapczyńska-Kordon, B. Effect of Compaction Pressure and Moisture Content on Post-Agglomeration Elastic Springback of Pellets. Materials 2021, 14, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Chandra, R.P.; Sokhansanj, S.; Saddler, J.N. The Role of Biomass Composition and Steam Treatment on Durability of Pellets. BioEnergy Res. 2018, 11, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, L.; Nielsen, N.P.K.; Stelte, W.; Dahl, J.; Ahrenfeldt, J.; Holm, J.K.; Puig Arnavat, M.; Bach, L.S.; Henriksen, U.B. Lab and Bench-Scale Pelletization of Torrefied Wood Chips—Process Optimization and Pellet Quality. Bioenerg. Res. 2014, 7, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colley, Z.; Fasina, O.O.; Bransby, D.; Lee, Y.Y. Moisture effect on the physical characteristics of switchgrass pellets. Am. Soc. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2006, 49, 1845–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adapa, P.K.; Tabil, L.G.; Schoenau, G.J. Compaction characteristics of barley, canola, oat, and wheat straw. Biosyst. Eng. 2009, 104, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumuluru, J.S. Effect of process variables on density and durability of pellets made from high moisture corn stover. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 119, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orisaleye, J.I.; Ojolo, S.J.; Ajiboye, J.S. Pressure buildup and wear analysis of tapered screw extruder biomass briquetting machines. Agric. Eng. Int. CIGR J. 2019, 21, 122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Orisaleye, J.I.; Ojolo, S.J.; Ajiboye, J.S. Mathematical modelling of die pressure of a screw briquetting machine. J. King Saud. Univ.-Eng. Sci. 2019, 32, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacova, M.; Matúš, M.; Krizan, P.; Beniak, J. Design theory for the pressing chamber in the solid biofuel production process. Acta Polytech. 2014, 54, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, R.; Yiyang, D.; Kruggel-Emden, H.; Zeng, T.; Lenz, V. Influence of pressure and retention time on briquette volume and raw density during biomass densification with an industrial stamp briquetting machine. Renew. Energy 2024, 229, 120773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamdem, B.M.; Lemaire, R.; Nikiema, J. Fuel briquettes produced via the co-treatment of wood sawdust, miscanthus and wheat straw: Physicochemical properties. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2025, 236, 121869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenda, M.; Horabik, J.; Parafiniuk, P.; Oniszczuk, A.; Bańda, M.; Wajs, J.; Gondek, E.; Chutkowski, M.; Lisowski, A.; Wiącek, J.; et al. Mechanical and Combustion Properties of Agglomerates of Wood of Popular Eastern European Species. Materials 2021, 14, 2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, M.A.; Conesa, J.A.; Garcia, M.D. Characterization and Production of Fuel Briquettes Made from Biomass and Plastic Wastes. Energies 2017, 10, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orisaleye, J.I.; Jekayinfa, S.O.; Ogundare, A.A.; Shituu, M.R.; Akinola, O.O.; Odesanya, K.O. Effects of Process Variables on Physico-Mechanical Properties of Abura (Mitrogyna ciliata) Sawdust Briquettes. Biomass 2024, 4, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudziak, M.; Knast, P.; Talaśka, K. Analysis of stability of stressed-skin constructions for transport of bulk raw materials. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 776, 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knast, P. Reduction of the value of the bend deflection arising due to external forces and gravity by applying the tensile stress to the axial alignment. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 776, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-ISO 3310-1; Tests for Geometrical Properties of Aggregates—Part 2: Determination of Particle Size Distribution—Test Sieves, Nominal Size of Apertures. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2021.

- ASTM E11; Standard Specification for Woven Wire Test Sieve Cloth and Test Sieves. Advancing Standards Transforming Markets: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- Cares-Pacheco, M.-G.; Cordeiro-Silva, E.; Gerardin, F.; Falk, V. Consistency in Young’s Modulus of Powders: A Review with Experiments. Powders 2024, 3, 280–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitzmann, W.; Buschhart, A. Pelleting as Prerequisite for the Energetic Utilization of by-Products of the Wood-Processing Industry; Amandus Kahl GmBH & Co.: Oslo, Norway, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Carone, M.T.; Pantaleo, A.; Pellerano, A. Influence of process parameters and biomass characteristics on the durability of pellets from the pruning residues of Olea europaea L. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Jun Ahn, B.; Ha Choi, D.; Han, G.S.; Jeong, H.S.; Ahn, S.H.; Yang, I. Effects of densification variables on the durability of wood pellets fabricated with Larix kaempferi C. and Liriodendron tulipifera L. sawdust. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 48, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, R.; Thyrel, M.; Sjöström, M.; Lestander, T.A. Effect of biomaterial characteristics on pelletizing properties and biofuel pellet quality. Fuel Process. Technol. 2009, 90, 1129–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, R.; González-Vázquez, M.P.; Pevida, C.; Rubiera, F. Pelletization properties of raw and torrefied pine sawdust: Effect of copelletization, temperature, moisture content and glycerol addition. Fuel 2018, 215, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frodeson, S.; Henriksson, G.; Berghel, J. Effects of moisture content during densification of biomass pellets, focusing on polysaccharide substances. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 122, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Particle Size S [mm] | Compaction Force F [kN] | Compaction Temperature T [°C] | Moisture M [%] | Density D [kg/m3] | Standard Deviation of Density σD | Young modulus E [MPa] | Standard Deviation of Young Modulus σE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 | 5 | 25 | 9 | 625.8 | 31.3 | 2246.38 | 134.7 |

| <1 | 5 | 100 | 9 | 996.7 | 69.8 | 1815.42 | 90.7 |

| <1 | 5 | 150 | 9 | 958.2 | 76.7 | 1734.03 | 104.1 |

| <1 | 5 | 200 | 9 | 975.7 | 19.5 | 1706.46 | 68.2 |

| <1 | 10 | 25 | 9 | 719.6 | 14.4 | 3693.53 | 147.7 |

| <1 | 10 | 100 | 9 | 1088.1 | 131.6 | 2893.23 | 318.2 |

| <1 | 10 | 150 | 9 | 1052.9 | 128.4 | 2893.54 | 289.3 |

| <1 | 10 | 200 | 9 | 1070.9 | 133.8 | 2951.51 | 354.1 |

| <1 | 15 | 25 | 9 | 955.9 | 119.4 | 4491.69 | 539 |

| <1 | 15 | 100 | 9 | 1317.3 | 165.9 | 3328.44 | 299.5 |

| <1 | 15 | 150 | 9 | 1291.9 | 164.1 | 3738.39 | 299.1 |

| <1 | 15 | 200 | 9 | 1311.8 | 167.9 | 3770.82 | 377.1 |

| <1 | 20 | 25 | 9 | 1101.4 | 132.1 | 5335.04 | 533.5 |

| <1 | 20 | 100 | 9 | 1456.8 | 180.6 | 4032.68 | 403.2 |

| <1 | 20 | 150 | 9 | 1439.7 | 175.6 | 4247.47 | 509.6 |

| <1 | 20 | 200 | 9 | 1461 | 179.7 | 4342.71 | 521.1 |

| <1 | 25 | 25 | 9 | 1199.9 | 149.9 | 6213.66 | 745.6 |

| <1 | 25 | 100 | 9 | 1549.4 | 195.2 | 5046.81 | 605.6 |

| <1 | 25 | 150 | 9 | 1540.4 | 195.6 | 4965.78 | 595.8 |

| <1 | 25 | 200 | 9 | 1563.3 | 190.7 | 4771.34 | 572.5 |

| 1–2.5 | 5 | 25 | 9 | 600.7 | 30.2 | 2134.06 | 128.2 |

| 1–2.5 | 5 | 100 | 9 | 956.8 | 66.9 | 1724.65 | 86.2 |

| 1–2.5 | 5 | 150 | 9 | 919.9 | 73.5 | 1647.33 | 98.8 |

| 1–2.5 | 5 | 200 | 9 | 936.6 | 18.7 | 1621.13 | 64.8 |

| 1–2.5 | 10 | 25 | 9 | 690.8 | 13.8 | 3508.85 | 140.3 |

| 1–2.5 | 10 | 100 | 9 | 1044.6 | 126.3 | 2748.57 | 302.3 |

| 1–2.5 | 10 | 150 | 9 | 1010.8 | 123.3 | 2748.86 | 274.8 |

| 1–2.5 | 10 | 200 | 9 | 1028.1 | 128.5 | 2803.93 | 336.4 |

| 1–2.5 | 15 | 25 | 9 | 917.7 | 114.7 | 4267.1 | 512.1 |

| 1–2.5 | 15 | 100 | 9 | 1264.6 | 159.3 | 3162.01 | 284.5 |

| 1–2.5 | 15 | 150 | 9 | 1240.3 | 157.5 | 3551.47 | 284.1 |

| 1–2.5 | 15 | 200 | 9 | 1259.4 | 161.1 | 3582.28 | 358.2 |

| 1–2.5 | 20 | 25 | 9 | 1057.4 | 126.8 | 5068.29 | 506.8 |

| 1–2.5 | 20 | 100 | 9 | 1398.5 | 173.4 | 3831.05 | 383.1 |

| 1–2.5 | 20 | 150 | 9 | 1382.1 | 168.6 | 4035.1 | 484.2 |

| 1–2.5 | 20 | 200 | 9 | 1402.6 | 172.5 | 4125.58 | 495.2 |

| 1–2.5 | 25 | 25 | 9 | 1151.9 | 143.9 | 5902.98 | 708.3 |

| 1–2.5 | 25 | 100 | 9 | 1487.4 | 187.4 | 4794.47 | 575.3 |

| 1–2.5 | 25 | 150 | 9 | 1478.8 | 187.8 | 4717.49 | 566.1 |

| 1–2.5 | 25 | 200 | 9 | 1500.8 | 183.1 | 4532.77 | 543.9 |

| 2.5–5 | 5 | 25 | 9 | 581.9 | 29.3 | 2089.14 | 125.3 |

| 2.5–5 | 5 | 100 | 9 | 926.9 | 64.8 | 1688.34 | 84.4 |

| 2.5–5 | 5 | 150 | 9 | 891.1 | 71.2 | 1612.65 | 96.7 |

| 2.5–5 | 5 | 200 | 9 | 907.4 | 18.1 | 1587.01 | 63.4 |

| 2.5–5 | 10 | 25 | 9 | 669.2 | 13.3 | 3434.98 | 137.3 |

| 2.5–5 | 10 | 100 | 9 | 1011.9 | 122.4 | 2246.38 | 295.9 |

| 2.5–5 | 10 | 150 | 9 | 979.2 | 119.4 | 1815.42 | 269.2 |

| 2.5–5 | 10 | 200 | 9 | 995.9 | 124.4 | 1734.03 | 229.3 |

| 2.5–5 | 15 | 25 | 9 | 889.1 | 111.1 | 1706.46 | 301.2 |

| 2.5–5 | 15 | 100 | 9 | 1225.1 | 154.3 | 3693.53 | 278.5 |

| 2.5–5 | 15 | 150 | 9 | 1201.5 | 152.5 | 2893.23 | 278.1 |

| 2.5–5 | 15 | 200 | 9 | 1220 | 156.1 | 2893.54 | 350.6 |

| 2.5–5 | 20 | 25 | 9 | 1024.3 | 122.9 | 2951.51 | 396.1 |

| 2.5–5 | 20 | 100 | 9 | 1354.8 | 167.9 | 4491.69 | 375.1 |

| 2.5–5 | 20 | 150 | 9 | 1338.9 | 163.3 | 3328.44 | 374.1 |

| 2.5–5 | 20 | 200 | 9 | 1358.7 | 167.1 | 3738.39 | 384.6 |

| 2.5–5 | 25 | 25 | 9 | 1115.9 | 139.4 | 3770.82 | 493. |

| 2.5–5 | 25 | 100 | 9 | 1440.9 | 181.5 | 5335.04 | 563.2 |

| 2.5–5 | 25 | 150 | 9 | 1432.6 | 181.9 | 4032.68 | 554.1 |

| 2.5–5 | 25 | 200 | 9 | 1453.9 | 177.3 | 4247.47 | 532.4 |

| >5 | 5 | 25 | 9 | 563.2 | 28.1 | 4342.71 | 221.3 |

| >5 | 5 | 100 | 9 | 897 | 62.7 | 6213.66 | 581.6 |

| >5 | 5 | 150 | 9 | 862.4 | 68.9 | 5046.81 | 493.6 |

| >5 | 5 | 200 | 9 | 878.1 | 17.5 | 4965.78 | 461.4 |

| >5 | 10 | 25 | 9 | 647.6 | 12.9 | 4771.34 | 332.9 |

| >5 | 10 | 100 | 9 | 979.3 | 118.4 | 2134.06 | 286.4 |

| >5 | 10 | 150 | 9 | 947.6 | 115.6 | 1724.65 | 260.4 |

| >5 | 10 | 200 | 9 | 963.9 | 120.4 | 1647.33 | 318.7 |

| >5 | 15 | 25 | 9 | 860.4 | 107.5 | 1621.13 | 185.1 |

| >5 | 15 | 100 | 9 | 1185.6 | 149.3 | 3508.85 | 269.6 |

| >5 | 15 | 150 | 9 | 1162.8 | 147.6 | 2748.57 | 269.1 |

| >5 | 15 | 200 | 9 | 1180.7 | 151.1 | 2748.86 | 339.3 |

| >5 | 20 | 25 | 9 | 991.3 | 118.9 | 2803.93 | 480.1 |

| >5 | 20 | 100 | 9 | 1311.1 | 162.5 | 4267.1 | 362.9 |

| >5 | 20 | 150 | 9 | 1295.7 | 158.4 | 3162.01 | 458.7 |

| >5 | 20 | 200 | 9 | 1314.9 | 161.7 | 3551.47 | 469.1 |

| >5 | 25 | 25 | 9 | 1079.9 | 134.9 | 3582.28 | 671.9 |

| >5 | 25 | 100 | 9 | 1394.4 | 175.6 | 5068.29 | 545.5 |

| >5 | 25 | 150 | 9 | 1386.4 | 176.1 | 3831.05 | 536.3 |

| >5 | 25 | 200 | 9 | 1406.9 | 171.6 | 4035.1 | 515.3 |

| <1 | 5 | 25 | 20 | 911.7 | 45.5 | 4125.58 | 207.6 |

| <1 | 5 | 100 | 20 | 1211.8 | 84.8 | 5902.98 | 119.6 |

| <1 | 5 | 150 | 20 | 1134.4 | 90.7 | 4794.47 | 144.7 |

| <1 | 5 | 200 | 20 | 964.3 | 19.2 | 4717.49 | 102.3 |

| <1 | 10 | 25 | 20 | 995.7 | 19.9 | 4532.77 | 166.2 |

| <1 | 10 | 100 | 20 | 1269.3 | 153.5 | 2089.14 | 408.7 |

| <1 | 10 | 150 | 20 | 1186.4 | 144.7 | 1688.34 | 398.7 |

| <1 | 10 | 200 | 20 | 1056.5 | 132.5 | 1612.65 | 332.3 |

| <1 | 15 | 25 | 20 | 1203 | 150.3 | 1587.01 | 228.2 |

| <1 | 15 | 100 | 20 | 1408.4 | 177.4 | 3434.98 | 416.7 |

| <1 | 15 | 150 | 20 | 1320.2 | 167.6 | 2690.71 | 328.5 |

| <1 | 15 | 200 | 20 | 1288.6 | 164.9 | 2690.99 | 397.7 |

| <1 | 20 | 25 | 20 | 1324.8 | 158.9 | 2744.9 | 263.9 |

| <1 | 20 | 100 | 20 | 1486 | 184.2 | 4177.27 | 496.9 |

| <1 | 20 | 150 | 20 | 1406.2 | 171.5 | 3095.44 | 467.2 |

| <1 | 20 | 200 | 20 | 1431.1 | 176.1 | 3476.7 | 242.3 |

| <1 | 25 | 25 | 20 | 1400.1 | 175.1 | 3506.86 | 301.9 |

| <1 | 25 | 100 | 20 | 1528.9 | 192.6 | 4961.59 | 499.7 |

| <1 | 25 | 150 | 20 | 1468.9 | 186.5 | 3750.39 | 227.5 |

| <1 | 25 | 200 | 20 | 1527.1 | 186.3 | 3950.15 | 448.4 |

| 1–2.5 | 5 | 25 | 20 | 863.2 | 43.1 | 4038.72 | 197.2 |

| 1–2.5 | 5 | 100 | 20 | 1147.3 | 80.3 | 5778.71 | 113.6 |

| 1–2.5 | 5 | 150 | 20 | 1074 | 85.9 | 4693.53 | 137.5 |

| 1–2.5 | 5 | 200 | 20 | 912.9 | 18.2 | 4618.18 | 97.2 |

| 1–2.5 | 10 | 25 | 20 | 942.7 | 18.8 | 4437.34 | 157.9 |

| 1–2.5 | 10 | 100 | 20 | 1201.7 | 145.4 | 2021.74 | 388.3 |

| 1–2.5 | 10 | 150 | 20 | 1123.3 | 137.3 | 1633.88 | 378.8 |

| 1–2.5 | 10 | 200 | 20 | 1000.3 | 125.4 | 1560.63 | 105.7 |

| 1–2.5 | 15 | 25 | 20 | 1139 | 142.3 | 1535.81 | 196.8 |

| 1–2.5 | 15 | 100 | 20 | 1333.5 | 168.1 | 3324.18 | 295.9 |

| 1–2.5 | 15 | 150 | 20 | 1249.9 | 158.7 | 2603.91 | 207.1 |

| 1–2.5 | 15 | 200 | 20 | 1220.1 | 156.1 | 2604.18 | 272.8 |

| 1–2.5 | 20 | 25 | 20 | 1254.3 | 150.5 | 2656.36 | 235.7 |

| 1–2.5 | 20 | 100 | 20 | 1406.9 | 174.4 | 4042.52 | 472.1 |

| 1–2.5 | 20 | 150 | 20 | 1331.4 | 162.4 | 2995.59 | 333.8 |

| 1–2.5 | 20 | 200 | 20 | 1354.9 | 166.6 | 3364.55 | 210.2 |

| 1–2.5 | 25 | 25 | 20 | 1325.7 | 165.7 | 3393.74 | 266.8 |

| 1–2.5 | 25 | 100 | 20 | 1447.6 | 182.3 | 4801.54 | 569.7 |

| 1–2.5 | 25 | 150 | 20 | 1390.8 | 176.6 | 3629.41 | 591.1 |

| 1–2.5 | 25 | 200 | 20 | 1445.9 | 176.3 | 3822.72 | 516.2 |

| 2.5–5 | 5 | 25 | 20 | 795.3 | 39.7 | 3908.44 | 293.1 |

| 2.5–5 | 5 | 100 | 20 | 1057.1 | 73.9 | 5592.3 | 211.2 |

| 2.5–5 | 5 | 150 | 20 | 989.6 | 79.1 | 4542.13 | 134.6 |

| 2.5–5 | 5 | 200 | 20 | 841.2 | 16.8 | 4469.21 | 195.1 |

| 2.5–5 | 10 | 25 | 20 | 868.6 | 17.3 | 4294.2 | 154.6 |

| 2.5–5 | 10 | 100 | 20 | 1107.2 | 133.9 | 3460.73 | 380.1 |

| 2.5–5 | 10 | 150 | 20 | 1034.9 | 126.2 | 2393.14 | 370.8 |

| 2.5–5 | 10 | 200 | 20 | 921.6 | 115.2 | 2412.71 | 495.1 |

| 2.5–5 | 15 | 25 | 20 | 1049.4 | 131.1 | 2558.51 | 584.3 |

| 2.5–5 | 15 | 100 | 20 | 1228.6 | 154.8 | 4156.29 | 387.6 |

| 2.5–5 | 15 | 150 | 20 | 1151.7 | 146.2 | 3715.98 | 398.5 |

| 2.5–5 | 15 | 200 | 20 | 1124.1 | 143.8 | 3987.62 | 462.9 |

| 2.5–5 | 20 | 25 | 20 | 1155.6 | 138.6 | 4436.46 | 524.4 |

| 2.5–5 | 20 | 100 | 20 | 1296.3 | 160.7 | 5235.83 | 462.1 |

| 2.5–5 | 20 | 150 | 20 | 1226.7 | 149.6 | 4631.09 | 620.5 |

| 2.5–5 | 20 | 200 | 20 | 1248.4 | 153.5 | 5357.4 | 597.3 |

| 2.5–5 | 25 | 25 | 20 | 1221.4 | 152.6 | 4977.76 | 652.7 |

| 2.5–5 | 25 | 100 | 20 | 1333.7 | 168.2 | 5639.09 | 557.7 |

| 2.5–5 | 25 | 150 | 20 | 1281.4 | 162.7 | 4969.39 | 676.5 |

| 2.5–5 | 25 | 200 | 20 | 1332.1 | 162.5 | 5560.33 | 603.1 |

| >5 | 5 | 25 | 20 | 766.2 | 38.3 | 5352.83 | 186.8 |

| >5 | 5 | 100 | 20 | 1018.4 | 71.2 | 5849.41 | 107.6 |

| >5 | 5 | 150 | 20 | 953.4 | 76.2 | 4998.18 | 130.2 |

| >5 | 5 | 200 | 20 | 810.4 | 16.2 | 6062.66 | 92.1 |

| >5 | 10 | 25 | 20 | 836.8 | 16.7 | 5404.1 | 149.6 |

| >5 | 10 | 100 | 20 | 1066.7 | 129.2 | 3287.69 | 367.8 |

| >5 | 10 | 150 | 20 | 997.1 | 121.6 | 2273.49 | 358.8 |

| >5 | 10 | 200 | 20 | 887.9 | 110.9 | 2292.07 | 479.1 |

| >5 | 15 | 25 | 20 | 1011 | 126.3 | 2430.58 | 465.4 |

| >5 | 15 | 100 | 20 | 1183.6 | 149.1 | 3948.48 | 375.1 |

| >5 | 15 | 150 | 20 | 1109.5 | 140.9 | 3530.18 | 385.7 |

| >5 | 15 | 200 | 20 | 1082.9 | 138.6 | 3788.24 | 447.9 |

| >5 | 20 | 25 | 20 | 1113.4 | 133.6 | 4214.64 | 407.5 |

| >5 | 20 | 100 | 20 | 1248.9 | 154.8 | 4974.04 | 447.2 |

| >5 | 20 | 150 | 20 | 1181.8 | 144.1 | 4399.54 | 600.5 |

| >5 | 20 | 200 | 20 | 1202.7 | 147.9 | 5089.53 | 578.1 |

| >5 | 25 | 25 | 20 | 1176.7 | 147.2 | 4728.87 | 631.7 |

| >5 | 25 | 100 | 20 | 1284.9 | 161.9 | 5357.13 | 539.8 |

| >5 | 25 | 150 | 20 | 1234.5 | 156.7 | 4720.92 | 654.7 |

| >5 | 25 | 200 | 20 | 1283.4 | 156.5 | 5282.32 | 583.6 |

| Name | Units | Type | Low | High |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle size, S | [mm] | Factor | <1 | >5 |

| Compaction force, F | [kN] | Factor | 5 | 25 |

| Temperature, T | [°C] | Factor | 25 | 200 |

| Moisture, M | [%] | Factor | 9 | 20 |

| Density, D | [kg/m3] | Response | 563.2 | 1563.3 |

| Young modulus, E | [MPa] | Response | 1535.8 | 6213.7 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df a | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 6.993 × 106 | 10 | 6.993 × 105 | 90.03 | <0.0001 | significant |

| S | 5.455 × 105 | 1 | 5.455 × 105 | 70.24 | <0.0001 | |

| F | 4.615 × 106 | 1 | 4.615 × 106 | 594.16 | <0.0001 | |

| T | 7.994 × 105 | 1 | 7.994 × 105 | 102.92 | <0.0001 | |

| M | 88,870.83 | 1 | 88,870.83 | 11.44 | 0.0009 | |

| S. F | 11907.50 | 1 | 11,907.50 | 1.53 | 0.2176 | |

| S. T | 1524.06 | 1 | 1524.06 | 0.1962 | 0.6584 | |

| S. M | 44,775.03 | 1 | 44,775.03 | 5.76 | 0.0176 | |

| F. T | 2565.38 | 1 | 2565.38 | 0.3303 | 0.5664 | |

| F. M | 1.345 × 105 | 1 | 1.345 × 105 | 17.32 | <0.0001 | |

| T. M | 3.529 × 105 | 1 | 3.529 × 105 | 45.43 | <0.0001 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df a | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 7.883 × 107 | 10 | 7.883 × 106 | 7.08 | <0.0001 | significant |

| S | 4.620 × 106 | 1 | 4.620 × 106 | 4.15 | 0.0434 | |

| F | 1.907 × 107 | 1 | 1.907 × 107 | 17.13 | <0.0001 | |

| T | 1.532 × 106 | 1 | 1.532 × 106 | 1.38 | 0.2427 | |

| M | 1.043 × 107 | 1 | 1.043 × 107 | 9.37 | 0.0026 | |

| S. F | 6.950 × 106 | 1 | 6.950 × 106 | 6.24 | 0.0136 | |

| S. T | 5.289 × 105 | 1 | 5.289 × 105 | 0.4750 | 0.4917 | |

| S. M | 8.638 × 106 | 1 | 8.638 × 106 | 7.76 | 0.0060 | |

| F. T | 1.640 × 106 | 1 | 1.640 × 106 | 1.47 | 0.2268 | |

| F. M | 1.911 × 107 | 1 | 1.911 × 107 | 17.16 | <0.0001 | |

| T. M | 8.710 × 105 | 1 | 8.710 × 105 | 0.7823 | 0.3779 |

| Input/Output Variable | Goal | Lower Limit | Upper Limit |

|---|---|---|---|

| S [mm] | is in range | <1 | >5 |

| F [kN] | minimize | 5 | 25 |

| T [°C] | minimize | 25 | 200 |

| M [%] | is in range | 9 | 20 |

| D [kg/m3] | maximize | 563.2 | 1563.3 |

| E [MPa] | maximize | 1535.8 | 6213.7 |

| S [mm] | F [kN] | T [°C] | M [%] | D [kg/m3] | E [MPa] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5–5 | 5 | 25 | 20 | 867 | 4737.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wilczyński, D.; Talaśka, K.; Wałęsa, K.; Wojtkowiak, D.; Warguła, Ł.; Domański, T.; Kubiak, M.; Saternus, Z.; Kołodziej, A.; Konecki, K.; et al. Studies on the Influence of Compaction Parameters on the Mechanical Properties of Oak Sawdust Briquettes. Materials 2026, 19, 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010119

Wilczyński D, Talaśka K, Wałęsa K, Wojtkowiak D, Warguła Ł, Domański T, Kubiak M, Saternus Z, Kołodziej A, Konecki K, et al. Studies on the Influence of Compaction Parameters on the Mechanical Properties of Oak Sawdust Briquettes. Materials. 2026; 19(1):119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010119

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilczyński, Dominik, Krzysztof Talaśka, Krzysztof Wałęsa, Dominik Wojtkowiak, Łukasz Warguła, Tomasz Domański, Marcin Kubiak, Zbigniew Saternus, Andrzej Kołodziej, Karol Konecki, and et al. 2026. "Studies on the Influence of Compaction Parameters on the Mechanical Properties of Oak Sawdust Briquettes" Materials 19, no. 1: 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010119

APA StyleWilczyński, D., Talaśka, K., Wałęsa, K., Wojtkowiak, D., Warguła, Ł., Domański, T., Kubiak, M., Saternus, Z., Kołodziej, A., Konecki, K., & Szulc, M. (2026). Studies on the Influence of Compaction Parameters on the Mechanical Properties of Oak Sawdust Briquettes. Materials, 19(1), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010119