High-Temperature Deformation Behavior of Powder Metallurgy Ti-4Zr-6Al-0.6Si-0.5Mo Alloy

Abstract

1. Introduction

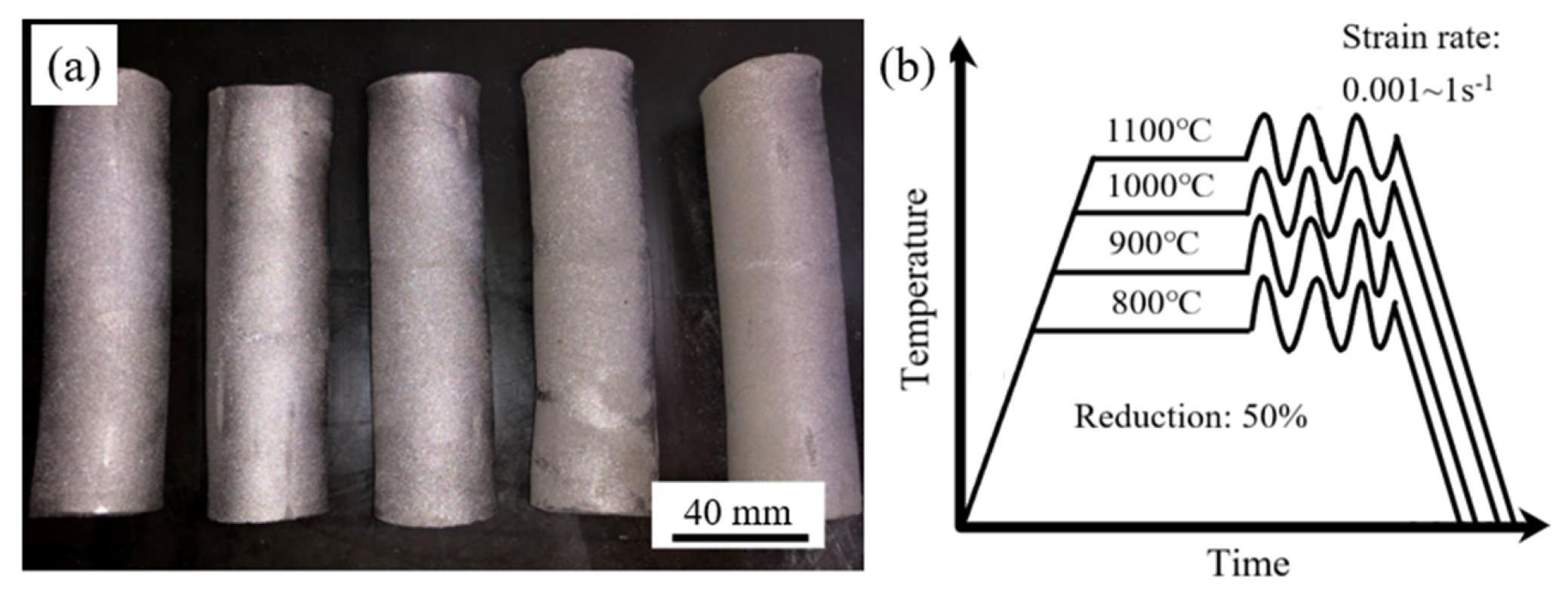

2. Experimental Procedure

3. Results and Discussion

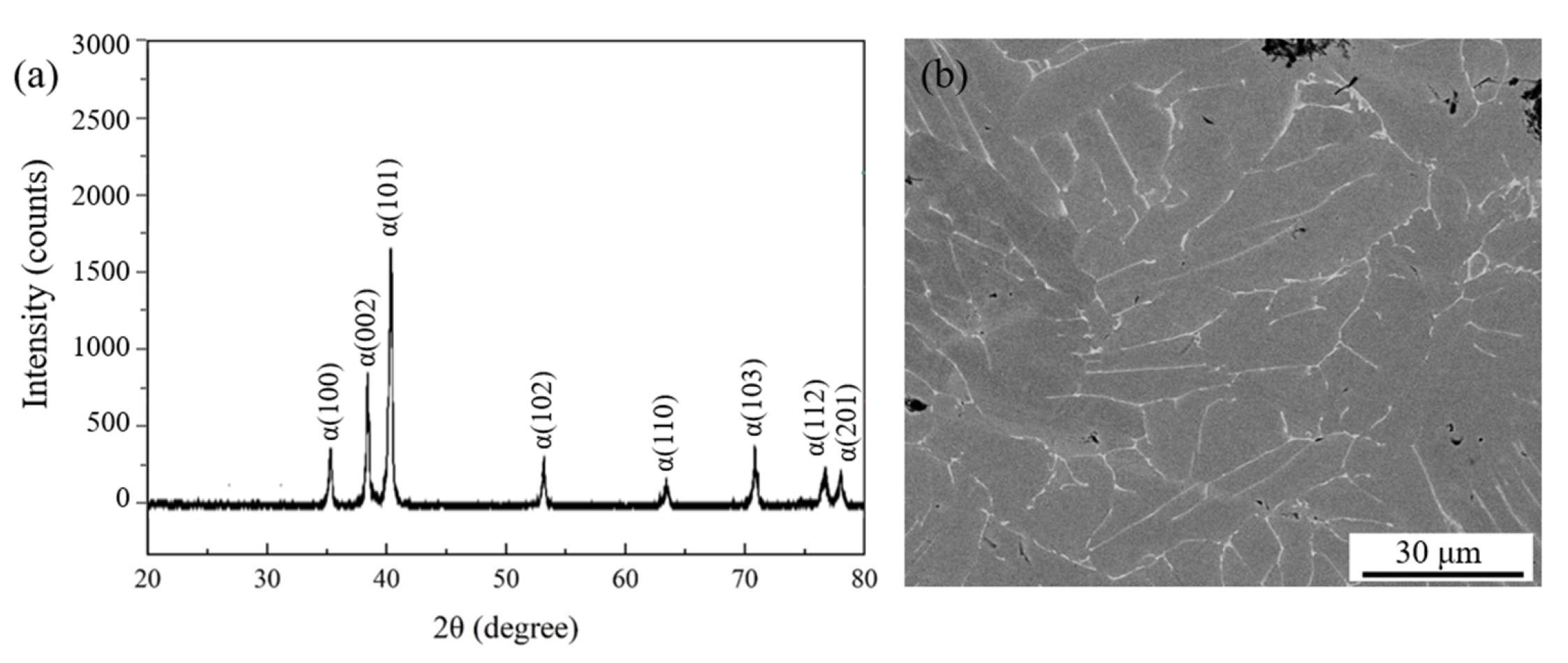

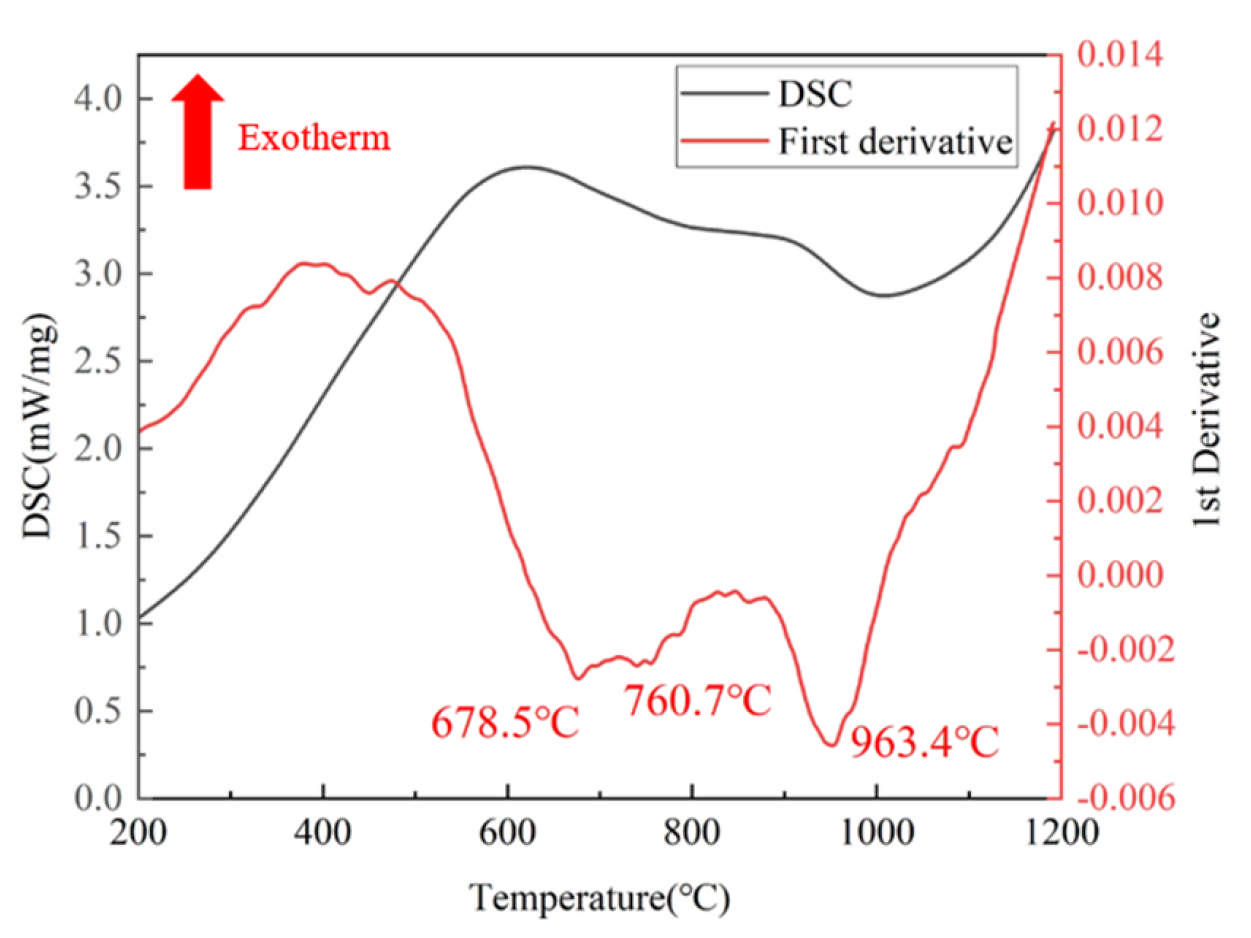

3.1. Initial Microstructure

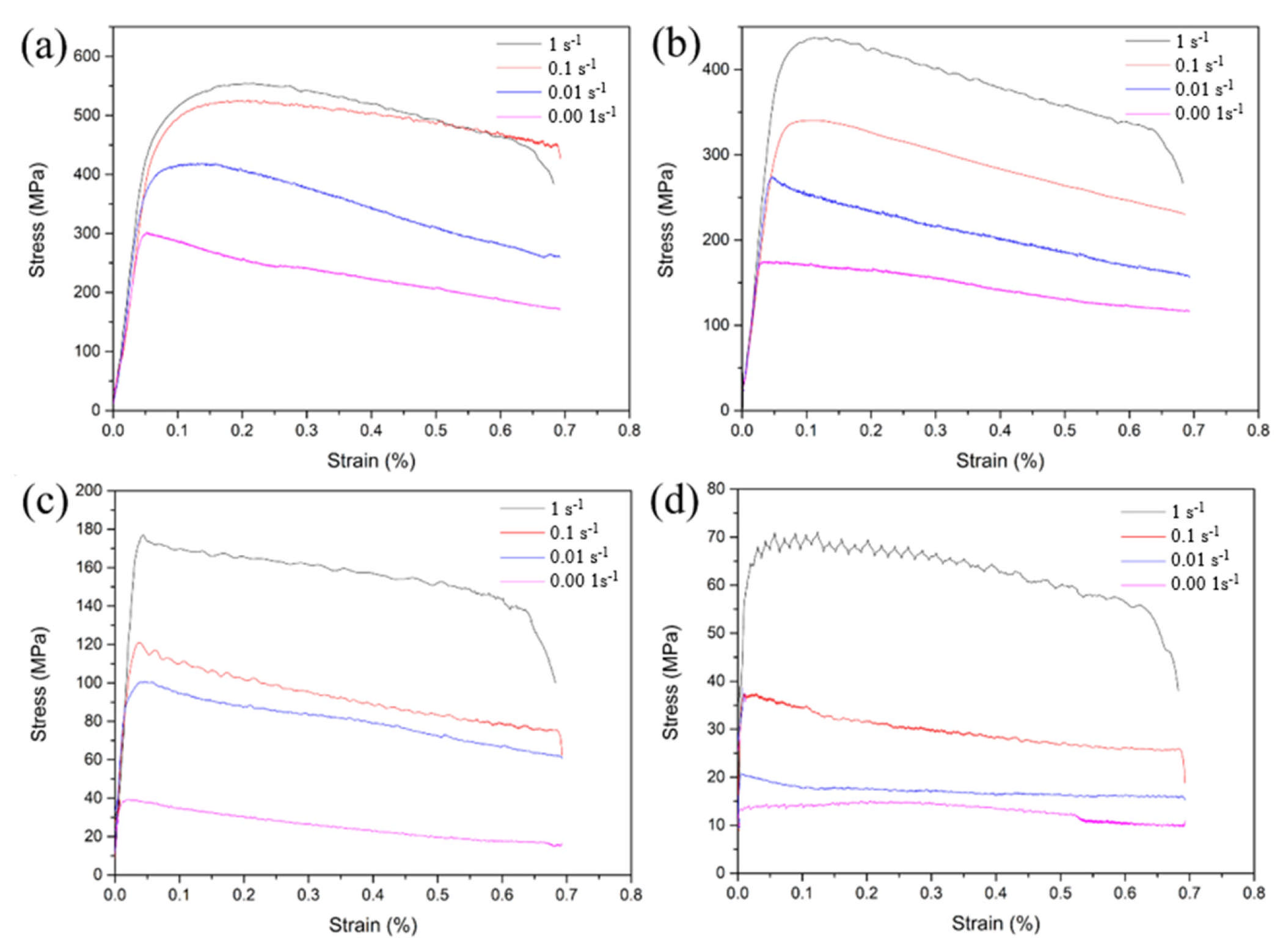

3.2. Flow Behavior

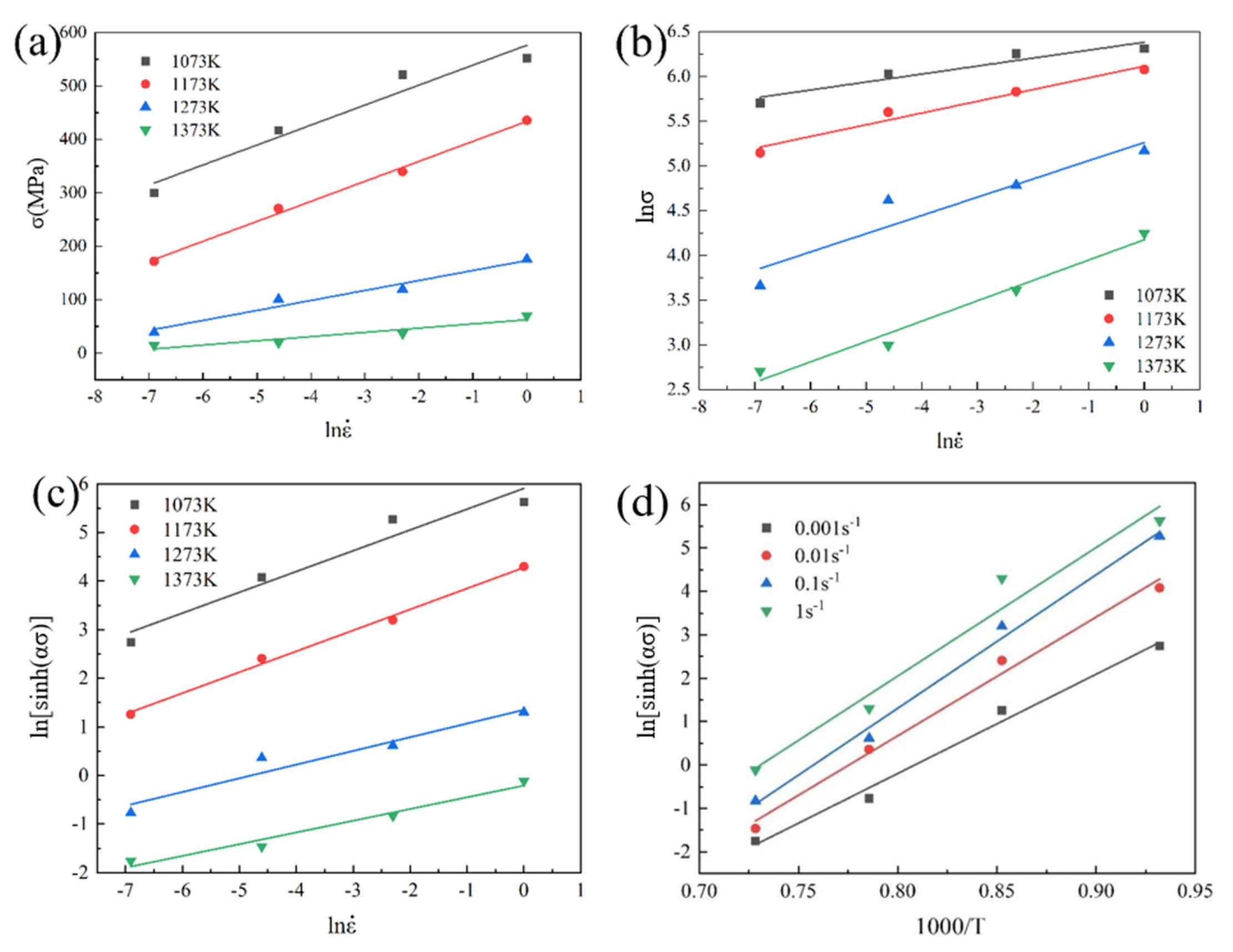

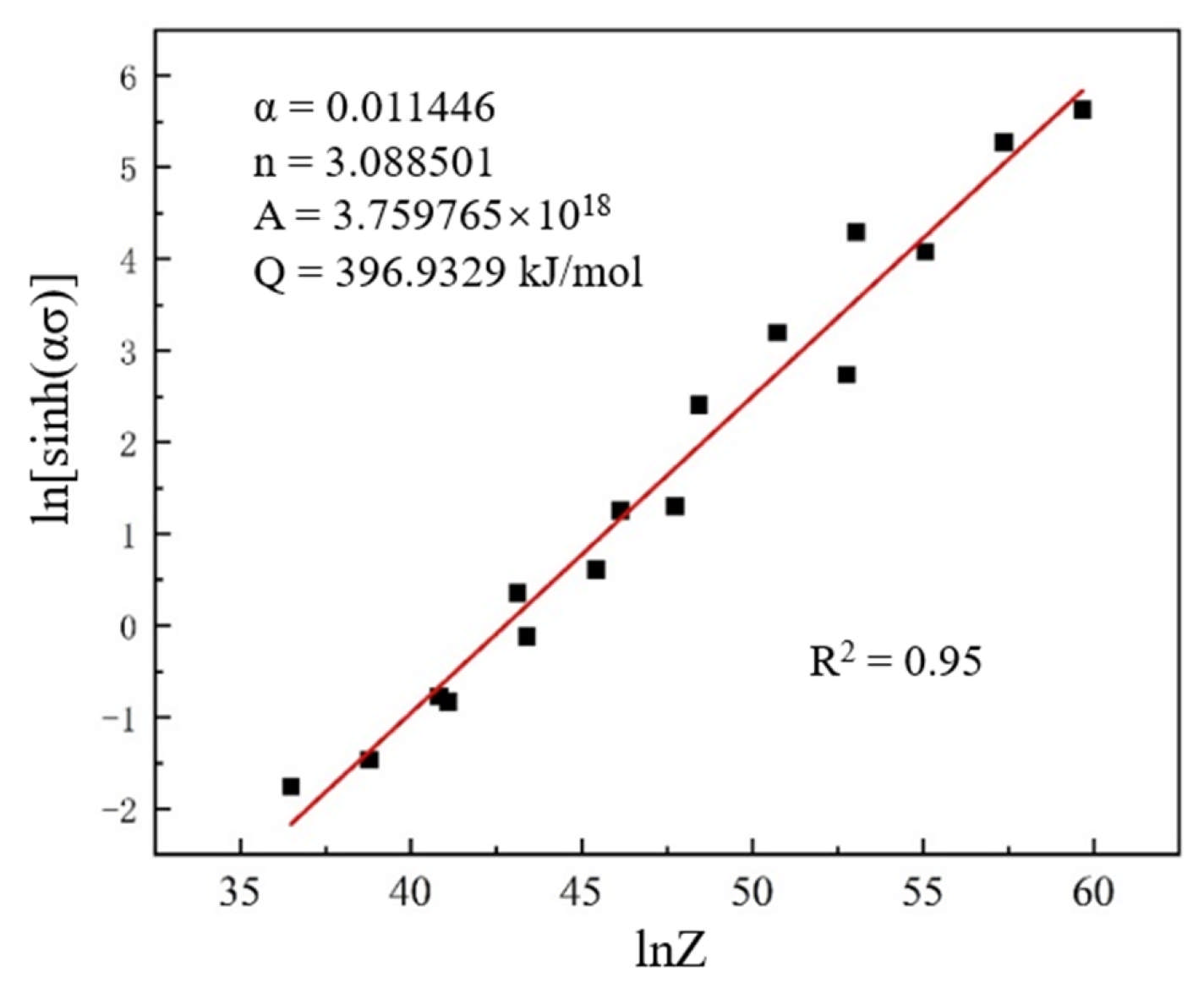

3.3. Constitutive Analysis

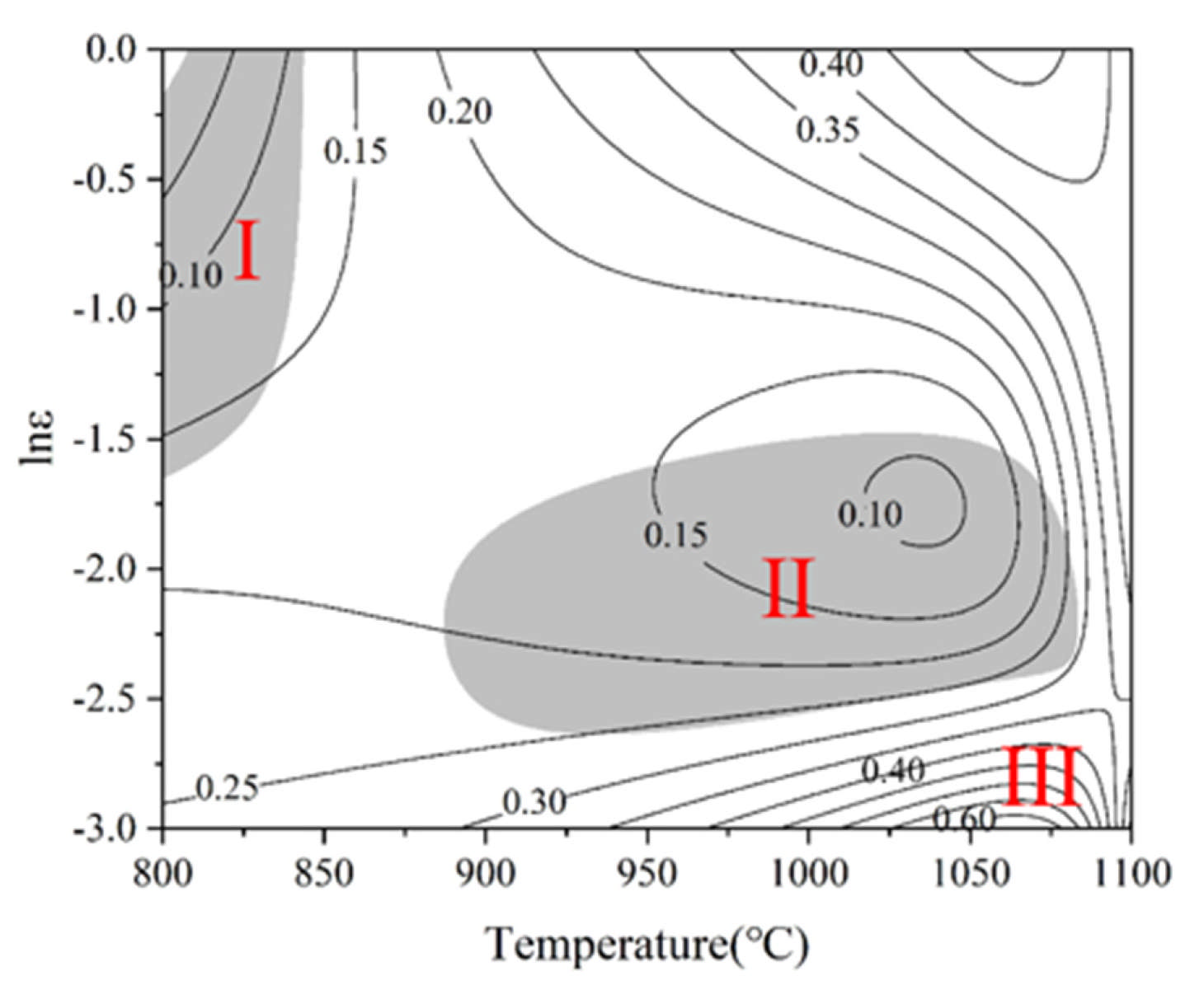

3.4. Processing Maps

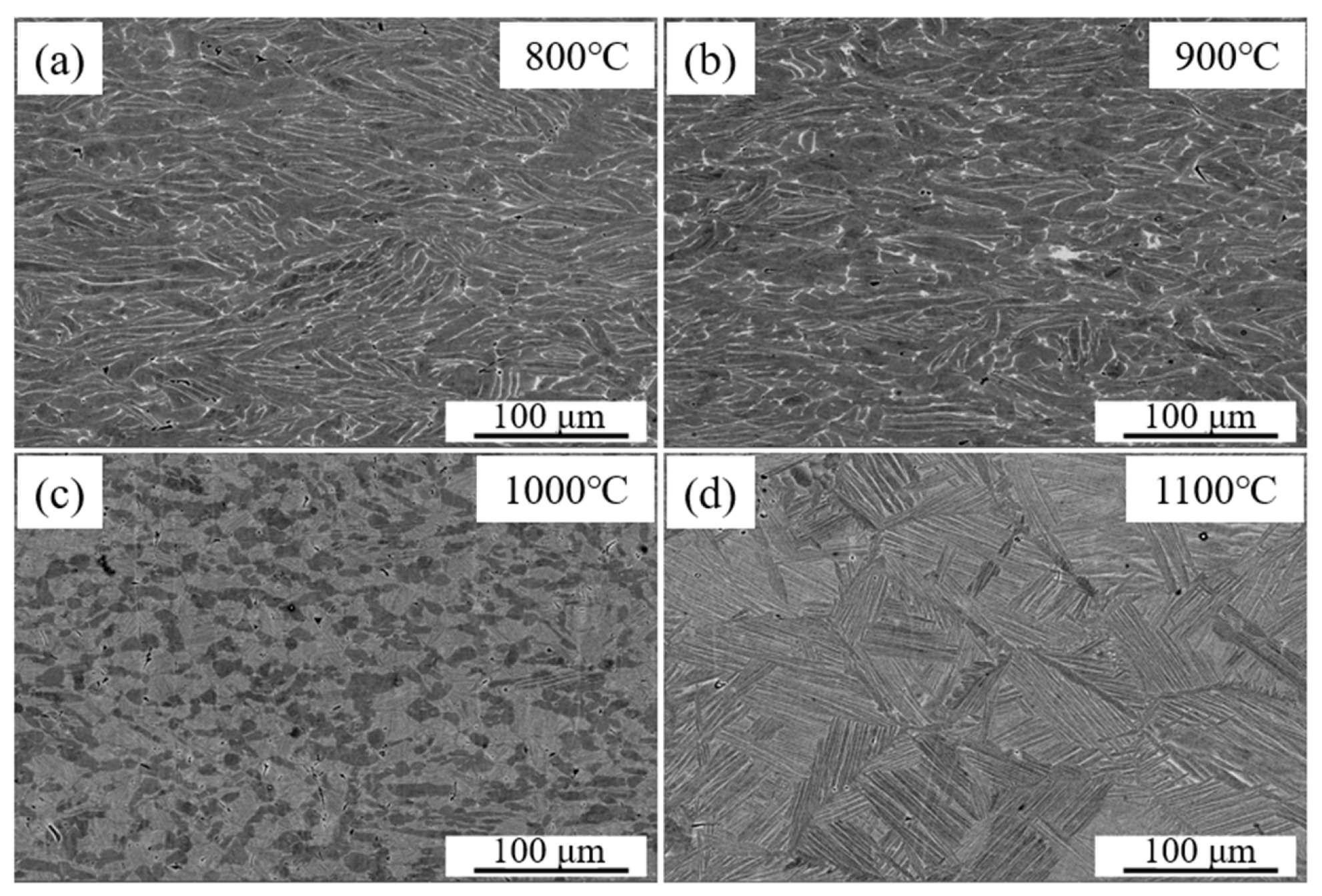

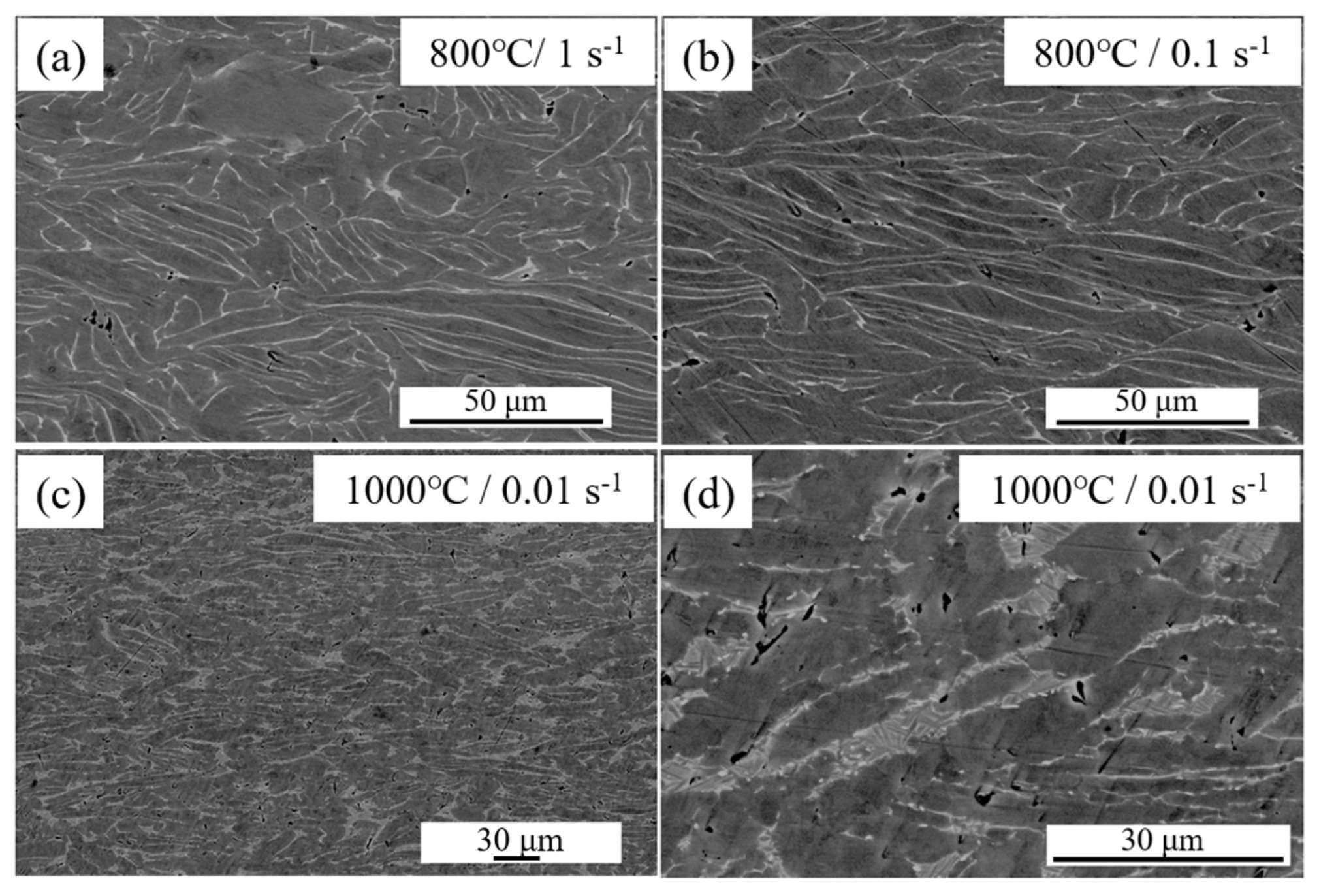

3.5. Hot Deformation Microstructure

4. Conclusions

- Ti-4Zr-6Al-0.6Si-0.5Mo alloy exhibits typical near-α titanium alloy microstructure, accompanied by a minor quantity of retained β phase located between α-phase lamellae.

- The alloy displays pronounced flow softening during high-temperature compression. The material’s flow stress is reduced by increasing temperature but enhanced by elevated strain rates.

- A processing map was constructed at 0.5 strain. Ideal hot processing occurs at 950–1100 °C with strain rates of 0.001–0.01 s−1. Flow instability occurred in two domains: 800–850 °C at 0.1–1 s−1 and 900–1075 °C at 0.01–0.1 s−1, where cracking is prone to occur, leading to processing failure and rendering these regions unsuitable for hot working.

- The deformation mechanism of Ti-4Zr-6Al-0.6Si-0.5Mo alloy at low temperatures (800–900 °C) is primarily localized flow or kinking, whereas at higher temperatures (1000–1100 °C), the dominant mechanisms are dynamic α-phase spheroidization and dynamic recrystallization. Microcracks emerged in high strain-rate zones, with crack density diminishing as strain rates decreased.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Germain, L.; Gey, N.; Humbert, M.; Vo, P.; Jahazi, M.; Bocher, P. Texture heterogeneities induced by subtransus processing of near α titanium alloys. Acta Mater. 2008, 56, 4298–4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Yang, R. Effect of heat treatment on the crystallographic orientation evolution in a near-α titanium alloy Ti60. Acta Mater. 2017, 131, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Deng, X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, L.; Guo, D. Hot and cold rolling of a novel near-α titanium alloy: Mechanical properties and underlying deformation mechanism. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 863, 144543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, A.; Liu, B.; Liu, B.; Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Liao, T.; Li, J.; Fang, Q.; Liaw, P.K.; Liu, Y. A novel cobalt-free oxide dispersion strengthened medium-entropy alloy with outstanding mechanical properties and irradiation resistance. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 152, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Deng, T.; Xiao, W.; Zhong, M.; Lai, Y.; Ojo, O.A. Effect of minor Sc modification on the high-temperature oxidation behavior of near-α Ti alloy. Corros. Sci. 2023, 217, 111122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczyńska-Zemła, D.; de Lucas, M.M.; Lavisse, L.; Zemła, M.; Herbst, F.; Pacorel, V.; Kwaśniak, P. Microstructural influence on high-temperature oxidation of near-α titanium alloys: Timetal 834 and 6242S. Corros. Sci. 2025, 255, 113081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, A.; Liu, B.; Li, Z.; Yang, T.; Cao, Y.; He, J.; Wang, B.; Li, J.; Fang, Q.; Cheng, X. Superb impact resistance of nano-precipitation-strengthened high-entropy alloys. Adv. Powder Mater. 2025, 4, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, B.; Wang, Z.; Nie, Z. A microstructure with improved thermal stability and creep resistance in a novel near-alpha titanium alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 731, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabie, V.M.; Li, C.; Saifu, W.; Li, J.; Xu, X. Mechanical properties of near alpha titanium alloys for high-temperature applications-a review. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 2020, 92, 521–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, A.; Liu, B.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Li, K.; Cao, Y.; Wang, B.; Han, L.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. A supersaturated super stainless high-entropy steel with extraordinary comprehensive performances for marine application. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 244, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhu, C.; He, J.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Zhou, K. Unexpected strengthening and toughening effects of B minor alloying in a new low-density near-α titanium alloy. Scr. Mater. 2025, 254, 116318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Wang, X.; Tian, P.; Zhuang, W.; Li, Y.; Ding, X.; Sun, J. Explosive compression strengthened a near-α titanium alloy with high strength. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1030, 180896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasundar, I.; Raghu, T.; Kashyap, B. Modeling the hot working behavior of near-α titanium alloy IMI 834. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2013, 23, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, P.; Jahazi, M.; Yue, S.; Bocher, P. Flow stress prediction during hot working of near-α titanium alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 447, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Deng, Y.; Liu, W.; Teng, H.; Wang, R.; Sun, C.; Deng, H.; Zhou, J. Substructure and texture evolution of a novel near-α titanium alloy with bimodal microstructure during hot compression in α + β phase region. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 996, 174869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hou, M.; Huang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Tan, C.; Xiao, H. Effect of Heat Treatment on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of a New Alpha-Titanium Alloy Ti-6.0 Al-3.0 Zr-0.5 Sn-1.0 Mo-1.5 Nb-1.0 V. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 12348–12358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, H.; Liu, D.; Jin, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y. Cooling rate–mediated evolution of lamellar α colony microtexture in a near-α titanium alloy during β processing. Mater. Des. 2025, 259, 114890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Liu, S.; Zang, M.; Zhang, D.; Cao, P.; Yang, W. Anomalous strain rate dependence of ultra-low temperature strength and ductility of an electron beam additively manufactured near alpha titanium alloy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 198, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Ye, P.; Fu, W.; Cao, G.; Han, Q.; Li, X.; Wu, H.; Fan, G. The effect of strain rate on macrozones of the α + β phase region during thermal deformation in near-α titanium alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 35, 2852–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Hou, M.; Yu, K.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, H. Flow behavior and dynamic recrystallization mechanism of a new near-alpha titanium alloy Ti-0.3 Mo-0.8 Ni-2Al-1.5 Zr. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 3863–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Chen, M.; Xie, L. Research on hot deformation behavior and numerical simulation of microstructure evolution for Ti–6Al–4V alloy. J. Mater. Res. 2024, 39, 1108–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, Q.; Mao, Y.; Wei, G.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, N. Achieving cryogenic strength-ductility synergy of near-α titanium alloy fabricated by laser direct energy deposition through multiscale deformation. Mater. Des. 2025, 259, 114858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, R.; Wang, W.; Hu, B.; Hu, H. Characterization and growth kinetics of borides layers on near-alpha titanium alloys. Materials 2024, 17, 4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, L.; Luo, Y.; Niu, Y.; Shao, Z. High-temperature hot deformation behavior and processing map of Ti-22Al-25Nb alloy. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Liu, B.; Xu, R.; Cao, Y.; Qiu, J.; Chen, F.; Yan, Z.; Liu, Y. Microstructure and mechanical properties of powder metallurgy high temperature titanium alloy with high Si content. Prog. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 777, 138993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghyan Fesharaki, M.; Atapour, M.; Nahvi, S.M.; Galati, M.; Saboori, A. Tribological response and microstructure evolution of electron beam powder bed fusion additively manufactured Ti–6Al–2Sn–4Zr–2Mo alloy. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Liu, D.; Cao, G.; Qu, S.; Feng, A.; Chen, D. Phase transformation-induced microstructural inhomogeneity in adiabatic shear bands of a metastable beta-titanium alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1039, 183187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhu, Z.; Song, M.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Q.; Dong, C. The equivalence of titanium alloys defined via β phase decomposition paths. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 1736–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandre, S.; Suresh, K.; Singh, S.K.; Sujith, R. A study on tensile flow and strain hardening behaviour of β-Titanium at elevated temperatures. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 2024, 238, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, T.; Wang, J.; Yang, Q. Microstructural evolution and high-temperature deformation mechanisms in TiB whisker-reinforced near-α titanium matrix composites after superplastic tensile deformation. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1044, 184163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Huang, W.; Liang, G.; Meng, Q.; Zhou, X.; Mao, B. Research Trends in Isothermal Near-Net-Shape Forming Process of High-Performance Titanium Alloys. Materials 2025, 18, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellars, C.; Tegart, W. Relationship between strength and structure in deformation at elevated temperatures. Mem. Sci. Rev. Met. 1966, 63, 731–746. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Shao, W.; Zhen, L.; Yang, L.; Zhang, X. Flow behavior and microstructures of superalloy 718 during high temperature deformation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 497, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Li, T.; Zhou, R. Flow behavior and microstructures of powder metallurgical CrFeCoNiMo0. 2 high entropy alloy during high temperature deformation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 689, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, B.; Zhu, Z.; Nie, Z. The high temperature deformation behavior and microstructure of TC21 titanium alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 5360–5367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, Y.; Rao, K. Processing maps and rate controlling mechanisms of hot deformation of electrolytic tough pitch copper in the temperature range 300–950 C. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 391, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshacharyulu, T.; Medeiros, S.; Frazier, W.; Prasad, Y. Hot working of commercial Ti–6Al–4V with an equiaxed α–β microstructure: Materials modeling considerations. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2000, 284, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubrahmanyam, V.; Prasad, Y. Deformation behaviour of beta titanium alloy Ti–10V–4.5 Fe–1.5 Al in hot upset forging. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2002, 336, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshacharyulu, T.; Medeiros, S.; Morgan, J.; Malas, J.; Frazier, W.; Prasad, Y. Hot deformation and microstructural damage mechanisms in extra-low interstitial (ELI) grade Ti–6Al–4V. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2000, 279, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshacharyulu, T.; Medeiros, S.; Frazier, W.; Prasad, Y. Microstructural mechanisms during hot working of commercial grade Ti–6Al–4V with lamellar starting structure. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2002, 325, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Hou, H.; Li, M.; Li, Z. High temperature deformation behavior of a near alpha Ti600 titanium alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 492, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, Y.; Seshacharyulu, T. Processing maps for hot working of titanium alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1998, 243, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements | Ti | Zr | Al | Mo | Si | C | N | O |

| Fraction | Bal. | 4.05 | 5.95 | 0.48 | 0.62 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.23 |

| Temperature (°C) | Strain Rate (s−1) | Flow Stress (MPa) |

|---|---|---|

| 800 | 0.001 | 301.4 ± 16.8 |

| 0.01 | 415.4 ± 12.3 | |

| 0.1 | 518.7 ± 20.1 | |

| 1 | 546.5 ± 25.6 | |

| 900 | 0.001 | 172.0 ± 9.1 |

| 0.01 | 268.1 ± 12.4 | |

| 0.1 | 339.1 ± 18.2 | |

| 1 | 435.1 ± 26.7 | |

| 1000 | 0.001 | 39.1 ± 3.5 |

| 0.01 | 99.3 ± 5.2 | |

| 0.1 | 119.9 ± 4.3 | |

| 1 | 172.9 ± 7.7 | |

| 1100 | 0.001 | 13.5 ± 2.1 |

| 0.01 | 20.2 ± 1.8 | |

| 0.1 | 37.3 ± 3.4 | |

| 1 | 65.1 ± 4.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Cao, Y.; Fang, Q.; Fu, A.; Liu, B. High-Temperature Deformation Behavior of Powder Metallurgy Ti-4Zr-6Al-0.6Si-0.5Mo Alloy. Materials 2026, 19, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010117

Li Z, Liu W, Wang J, Cao Y, Fang Q, Fu A, Liu B. High-Temperature Deformation Behavior of Powder Metallurgy Ti-4Zr-6Al-0.6Si-0.5Mo Alloy. Materials. 2026; 19(1):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010117

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zongshu, Wentao Liu, Jian Wang, Yuankui Cao, Qihong Fang, Ao Fu, and Bin Liu. 2026. "High-Temperature Deformation Behavior of Powder Metallurgy Ti-4Zr-6Al-0.6Si-0.5Mo Alloy" Materials 19, no. 1: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010117

APA StyleLi, Z., Liu, W., Wang, J., Cao, Y., Fang, Q., Fu, A., & Liu, B. (2026). High-Temperature Deformation Behavior of Powder Metallurgy Ti-4Zr-6Al-0.6Si-0.5Mo Alloy. Materials, 19(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010117