The Effect of Ageing on the Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Al-Zn-Mg Alloy

Abstract

1. Introduction

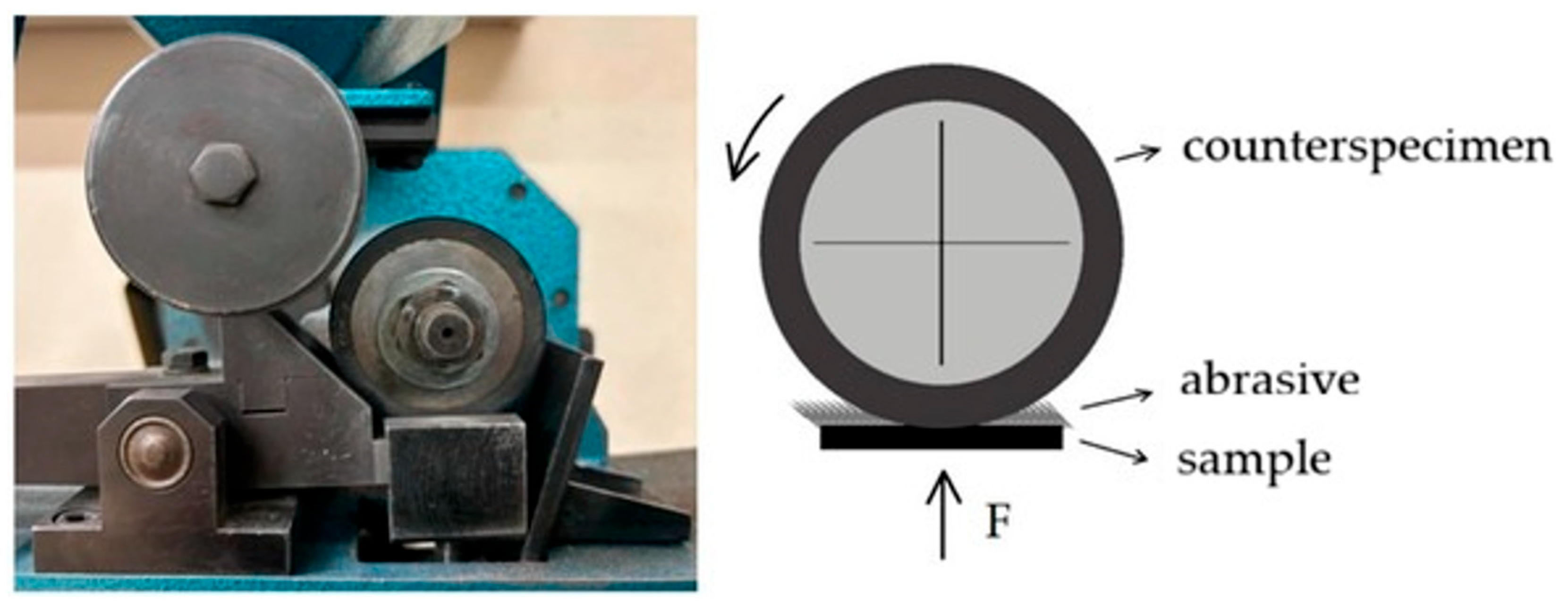

2. Materials and Methods

- kb—coefficient of relative abrasion resistance [dimensionless],

- Zww—mass consumption of the standard sample [g],

- Zwb—mass consumption of the tested sample [g],

- Nw—number of rotations of the rubber-rimmed steel wheel during the test of the standard sample,

- Nb—number of rotations of the rubber-rimmed steel wheel during the test of the tested sample,

- ρw, ρb—material density of the standard sample and tested sample [g/cm3].

3. Results

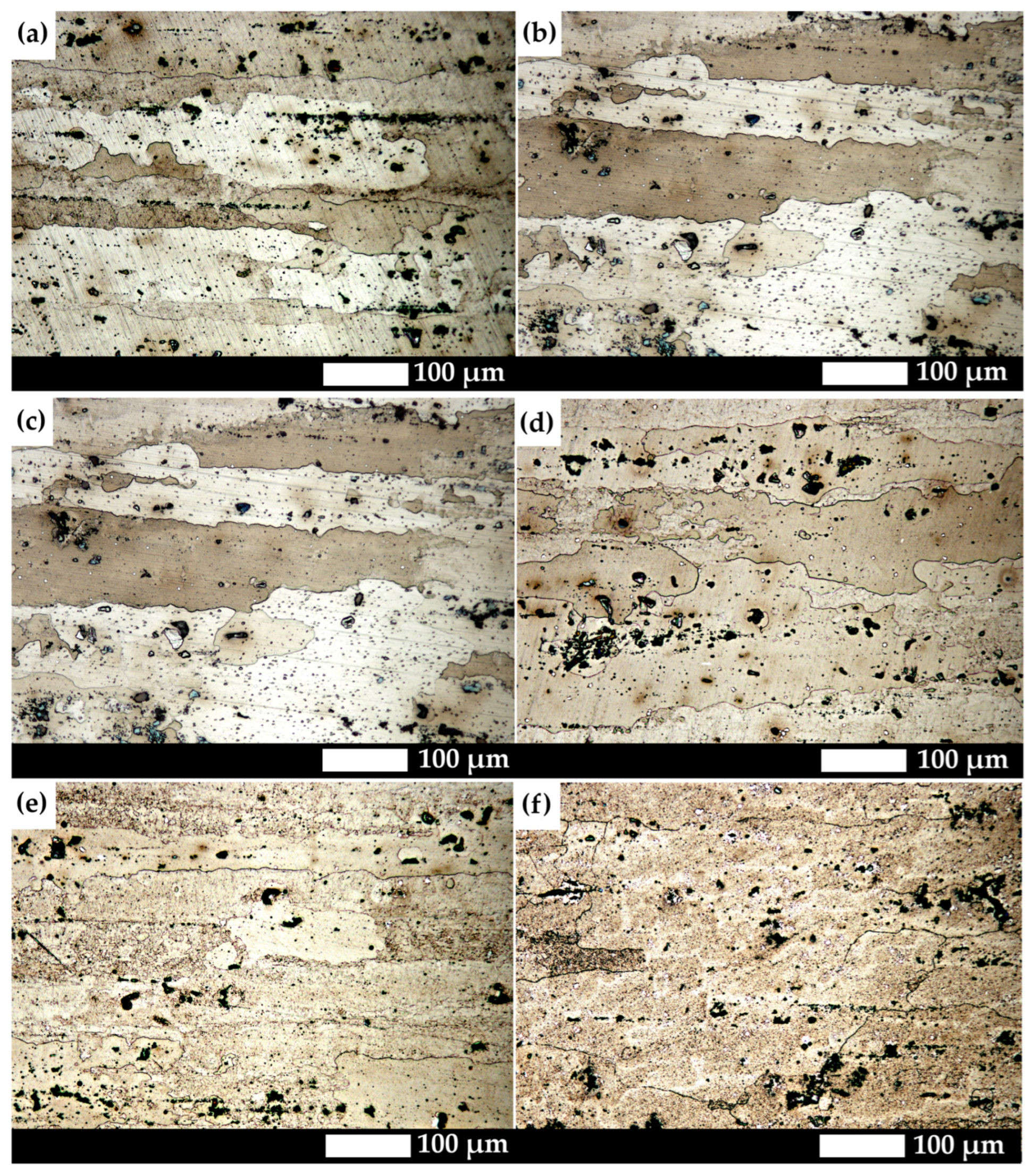

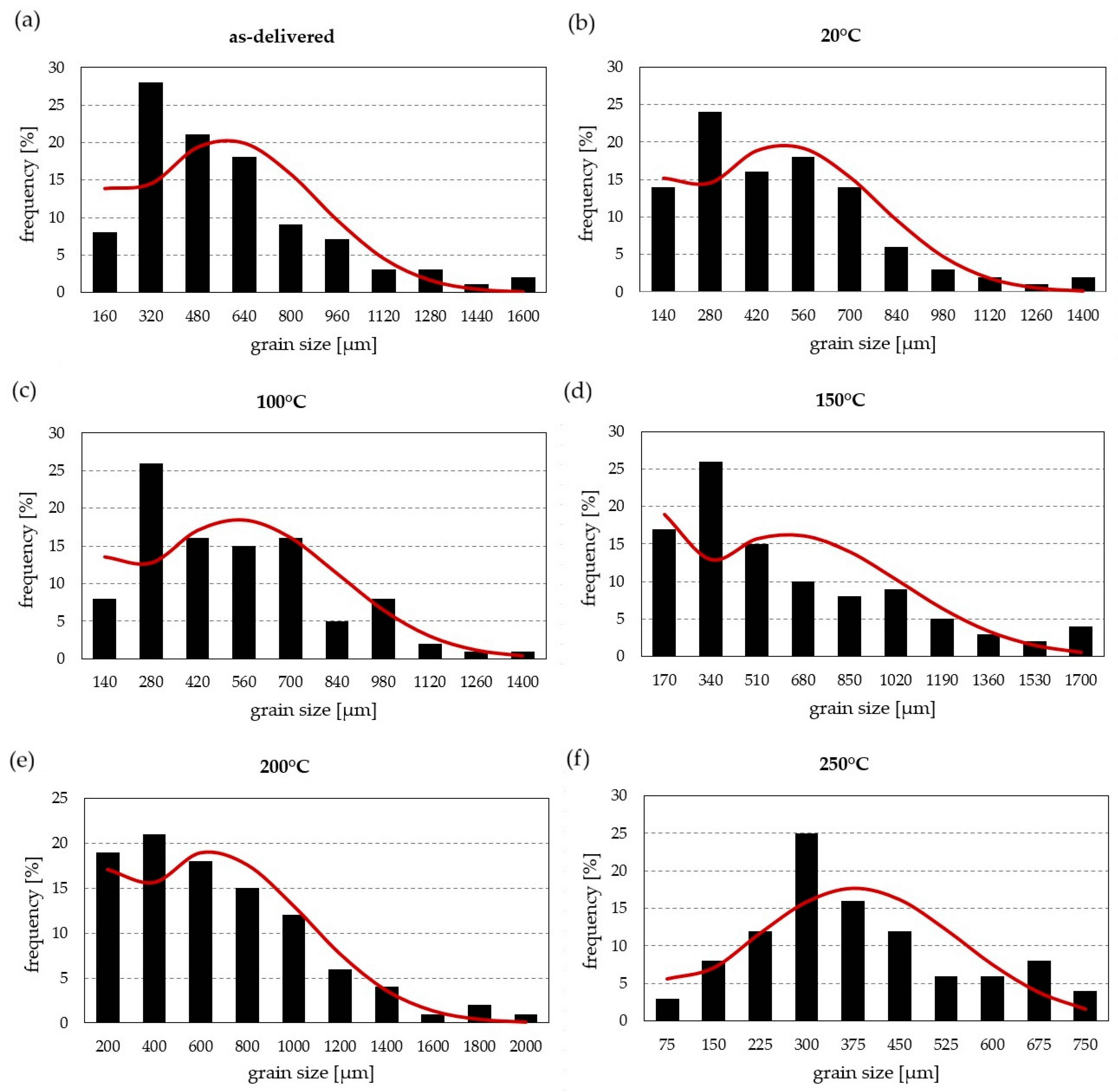

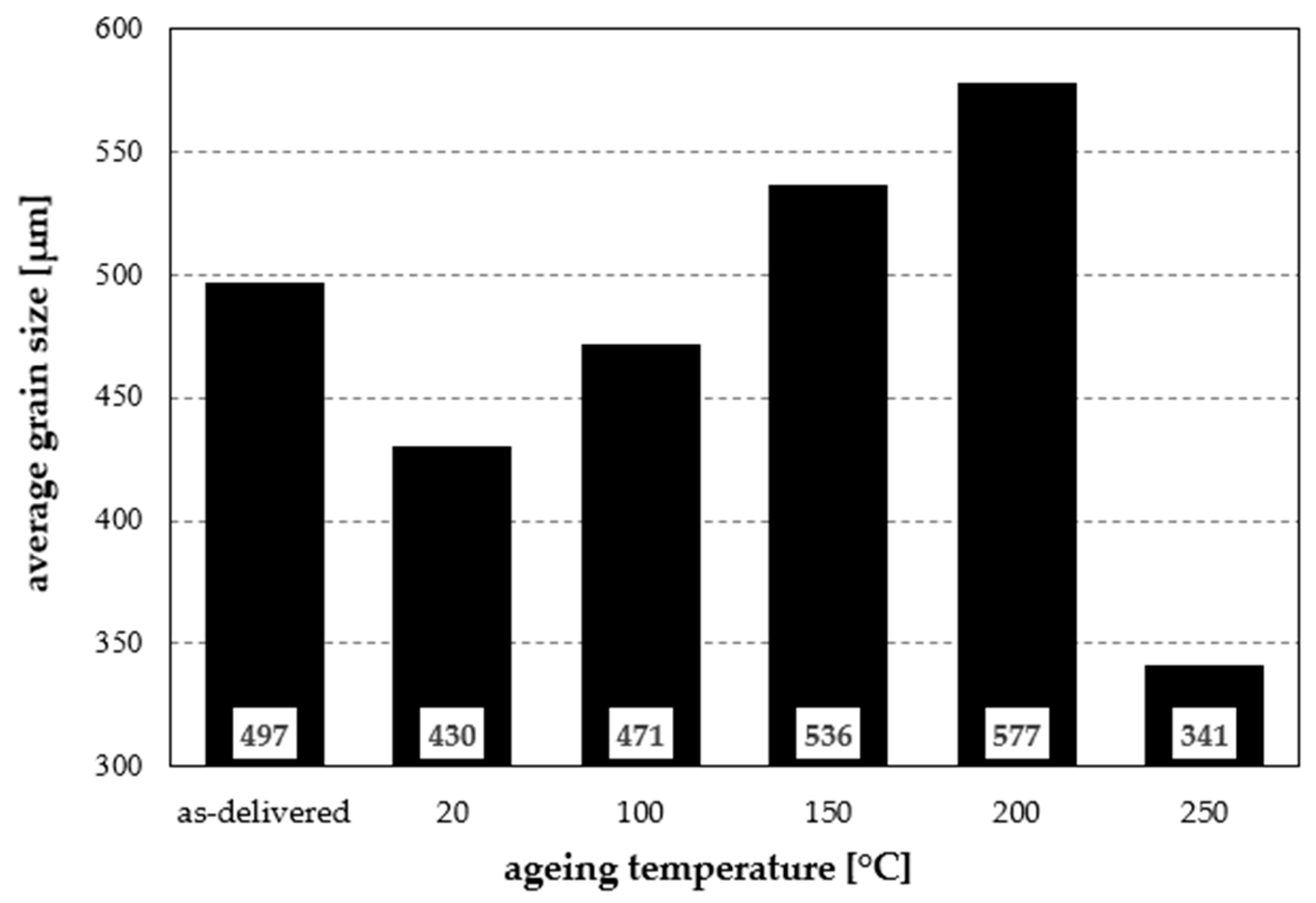

3.1. Materials Analysis

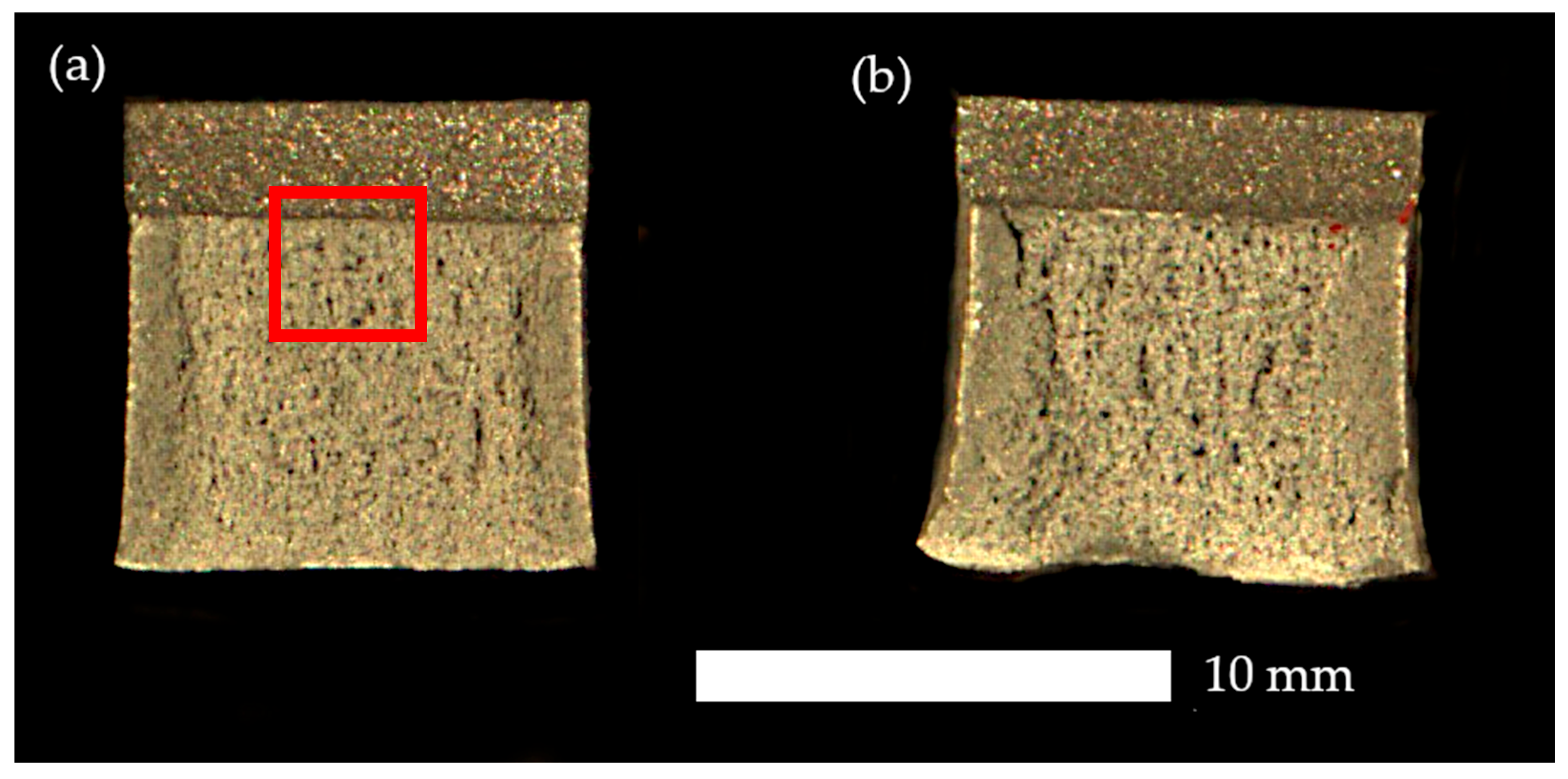

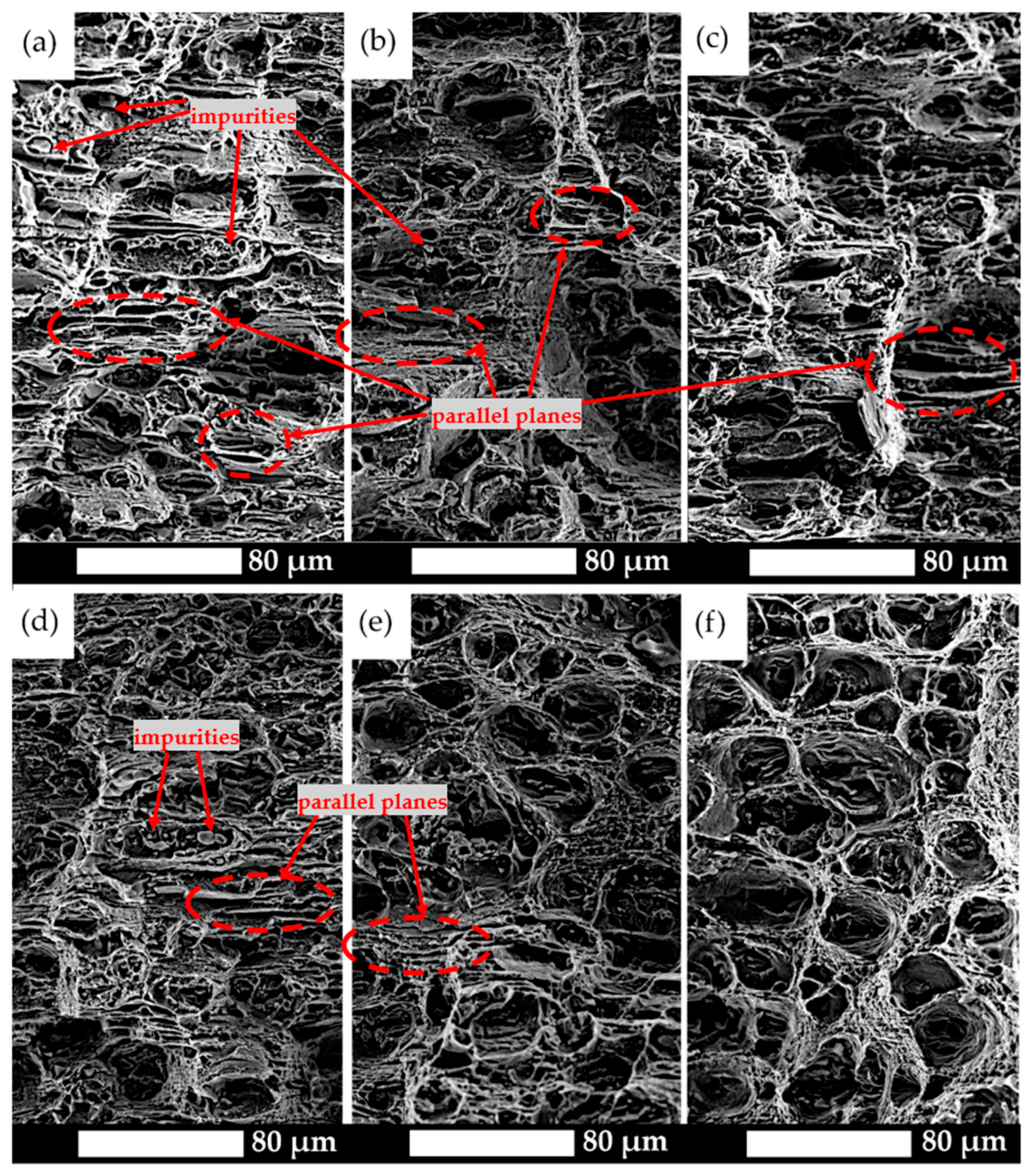

3.2. Impact Strength and Fractographic Analysis

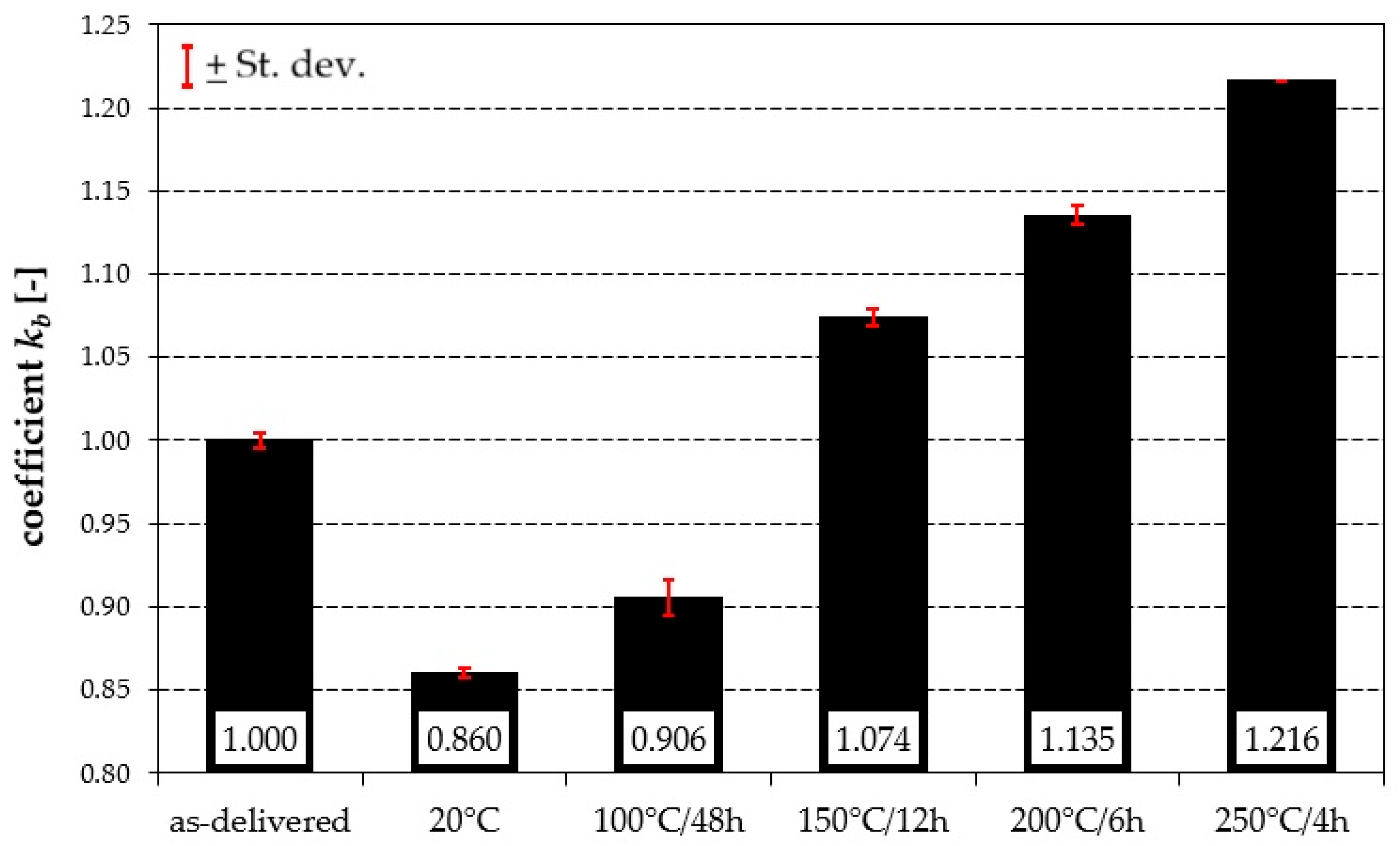

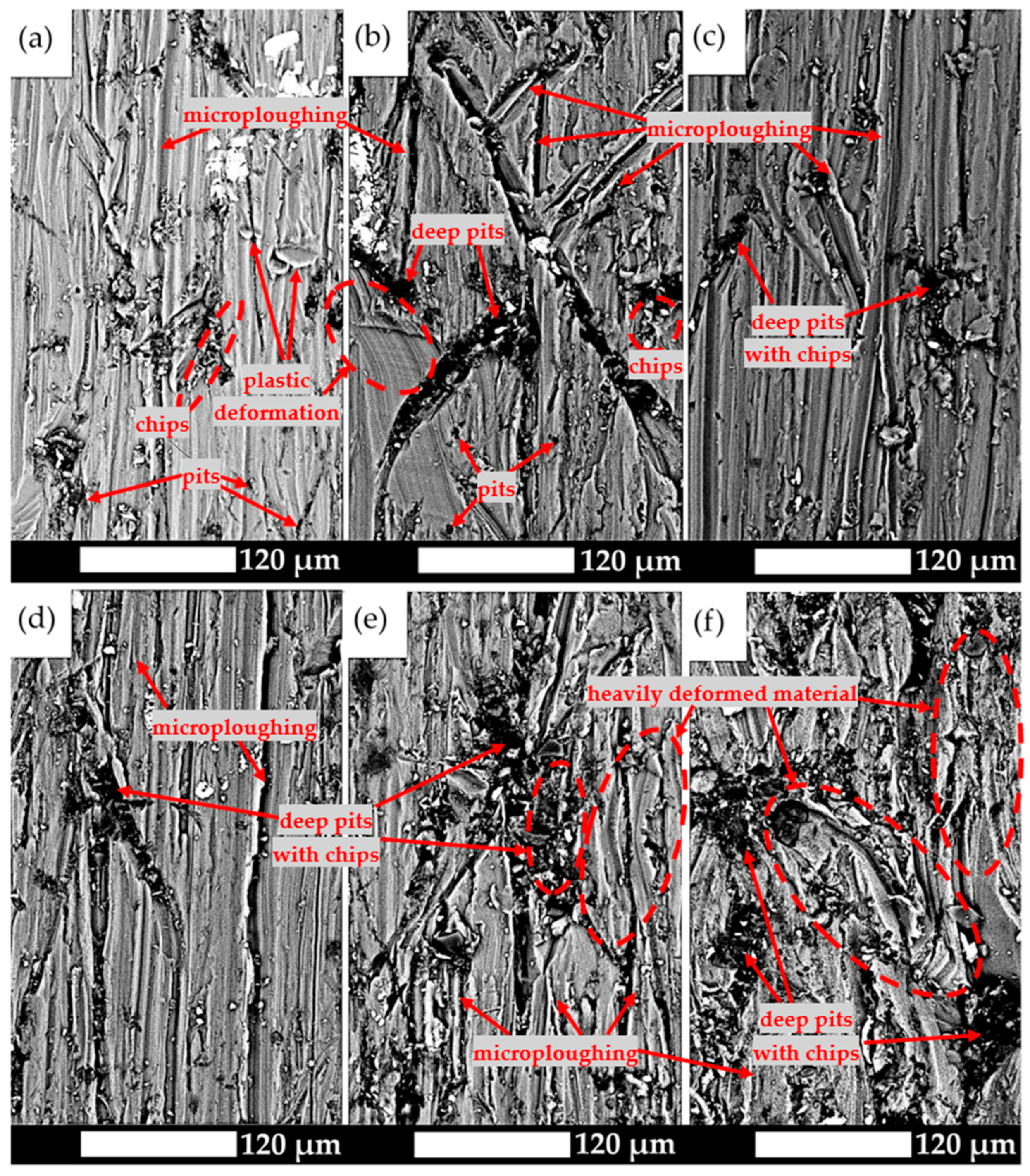

3.3. Abrasive Wear Resistance Tests

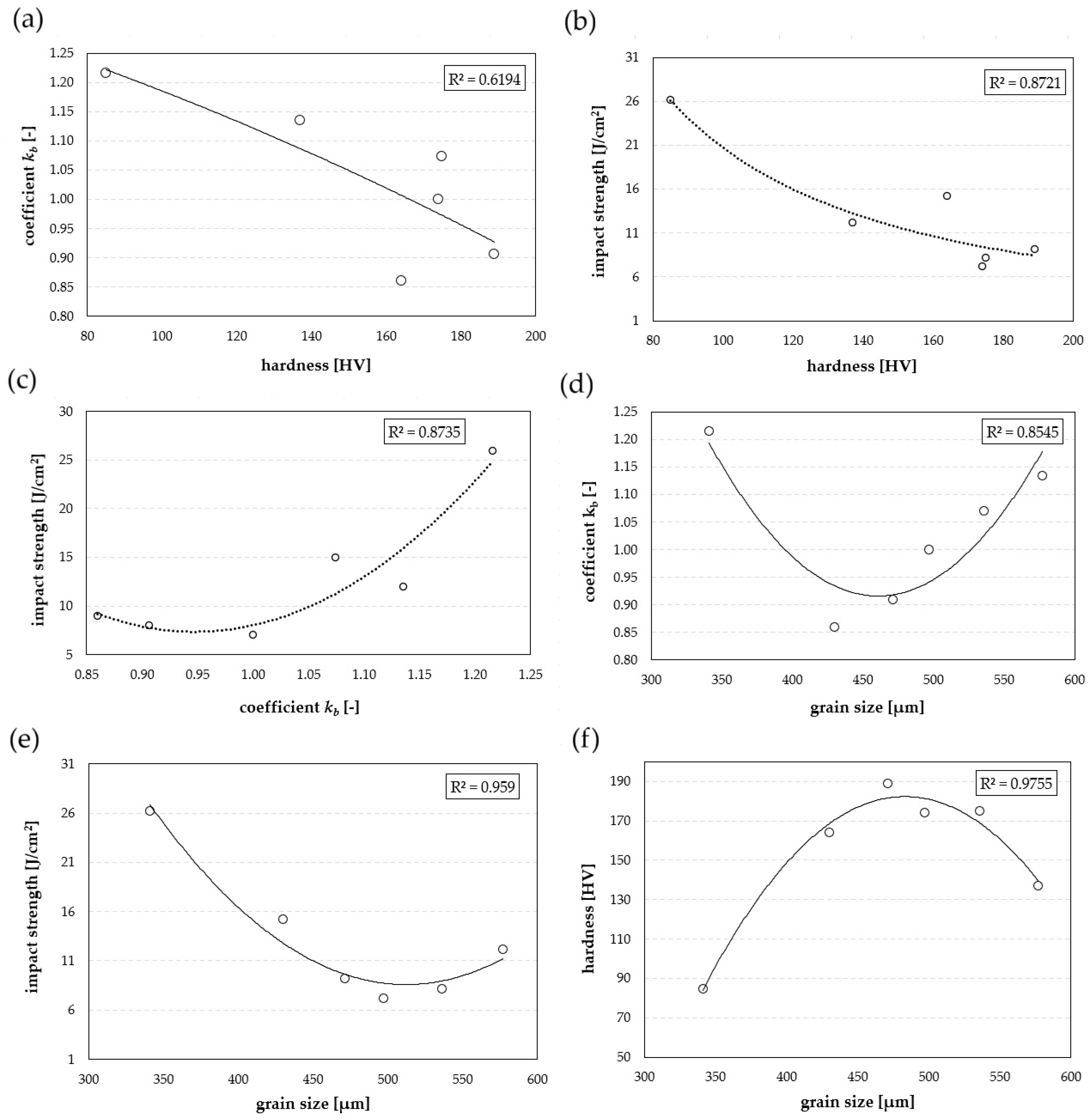

4. Discussion

- IZ—the volumetric wear loss (m3),

- k—the wear coefficient,

- P—the normal load (N),

- l—the sliding distance (m),

- H—the hardness of the softest contacting surfaces (N/m2).

5. Conclusions

- In the as-delivered condition and after natural ageing, the microstructure of the Al 7075 alloy is characterised by banded, elongated grains and fine secondary-phase precipitates. With increasing ageing temperature, coagulation of these precipitates and recrystallisation processes occur, leading to the formation of more isotropic grains.

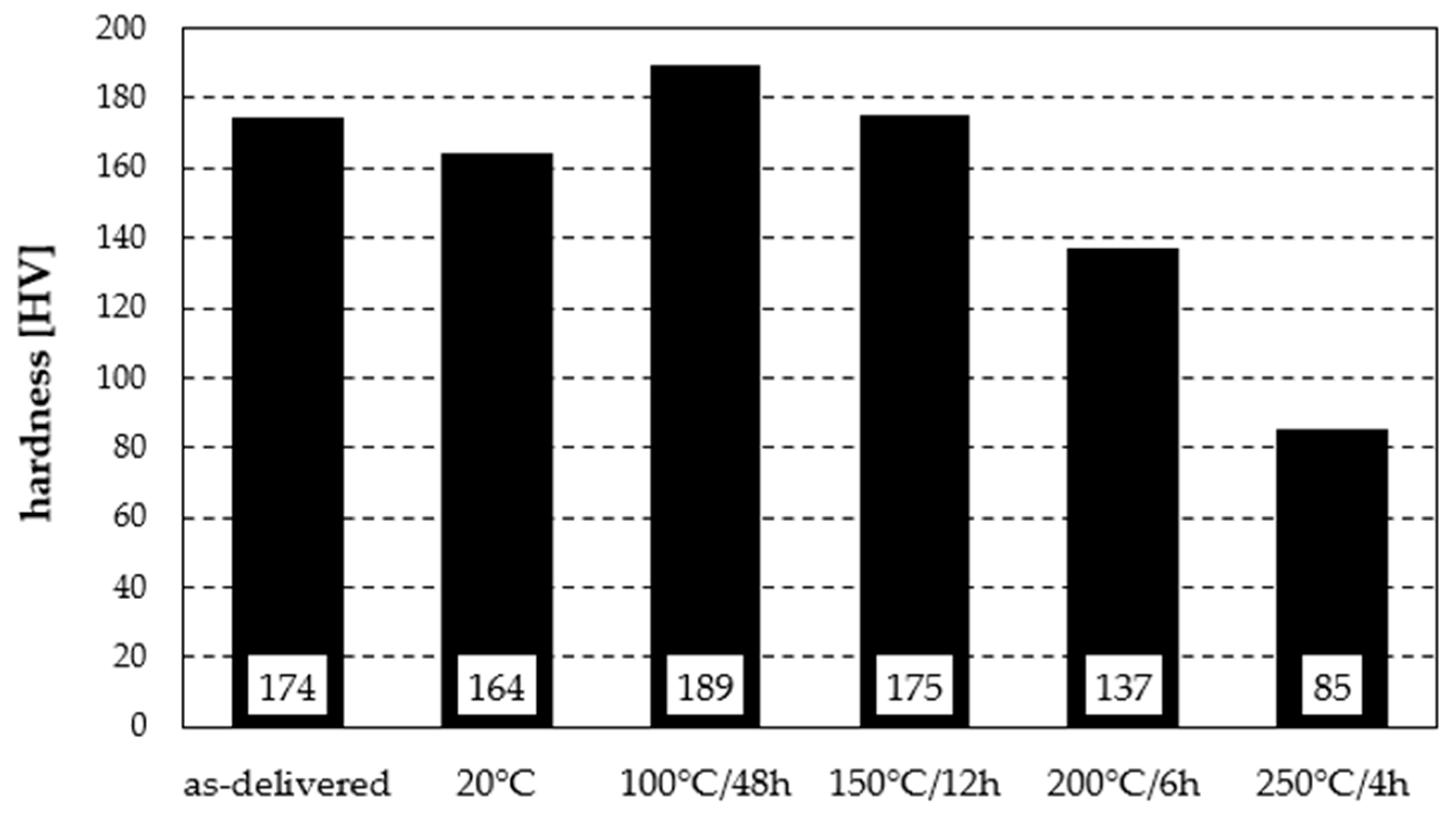

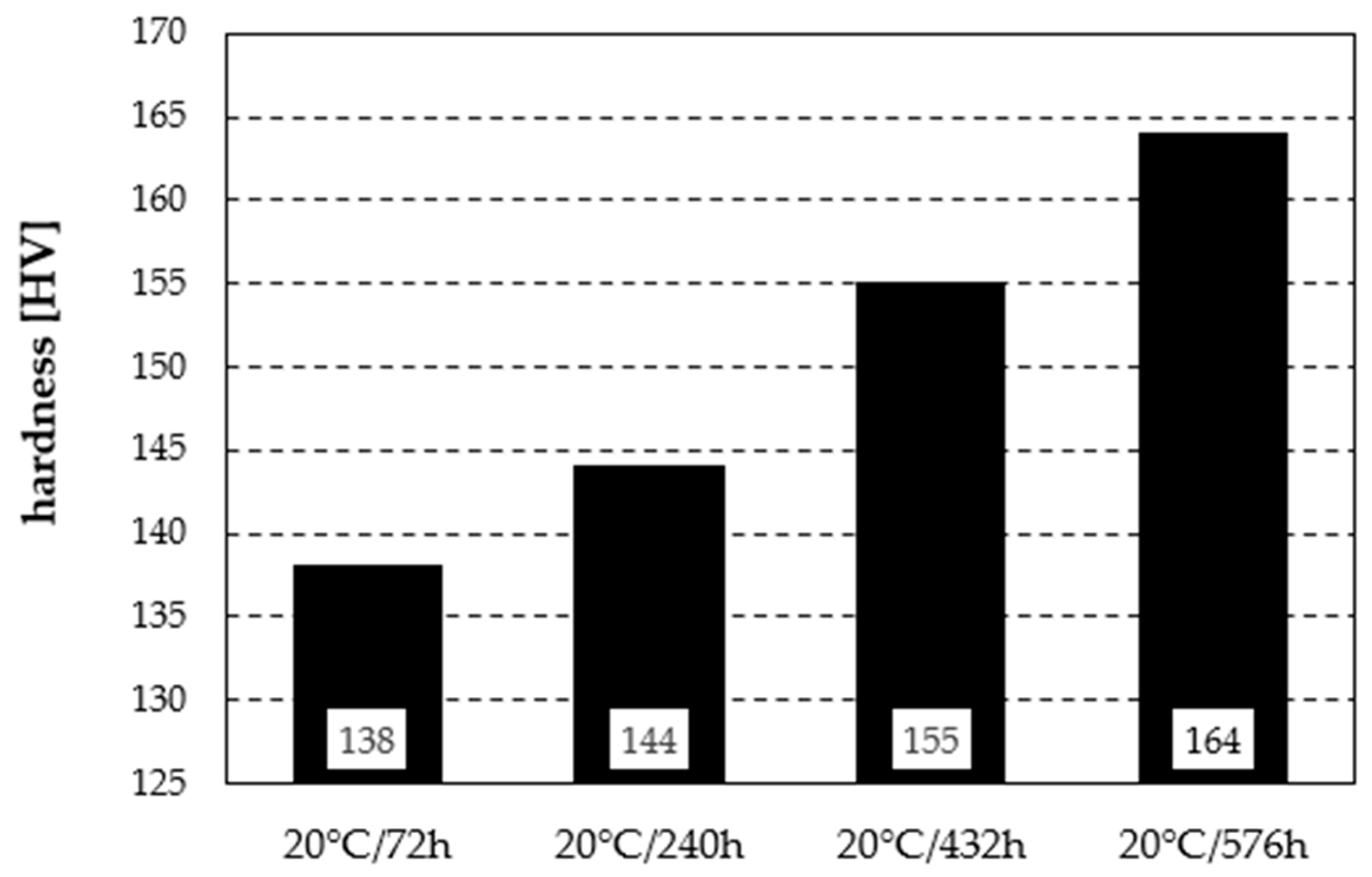

- The highest hardness (189 HV) was obtained after ageing at 100 °C/48 h, whereas increasing the temperature above 150 °C caused a systematic decrease in hardness—down to 85 HV after ageing at 250 °C/4 h.

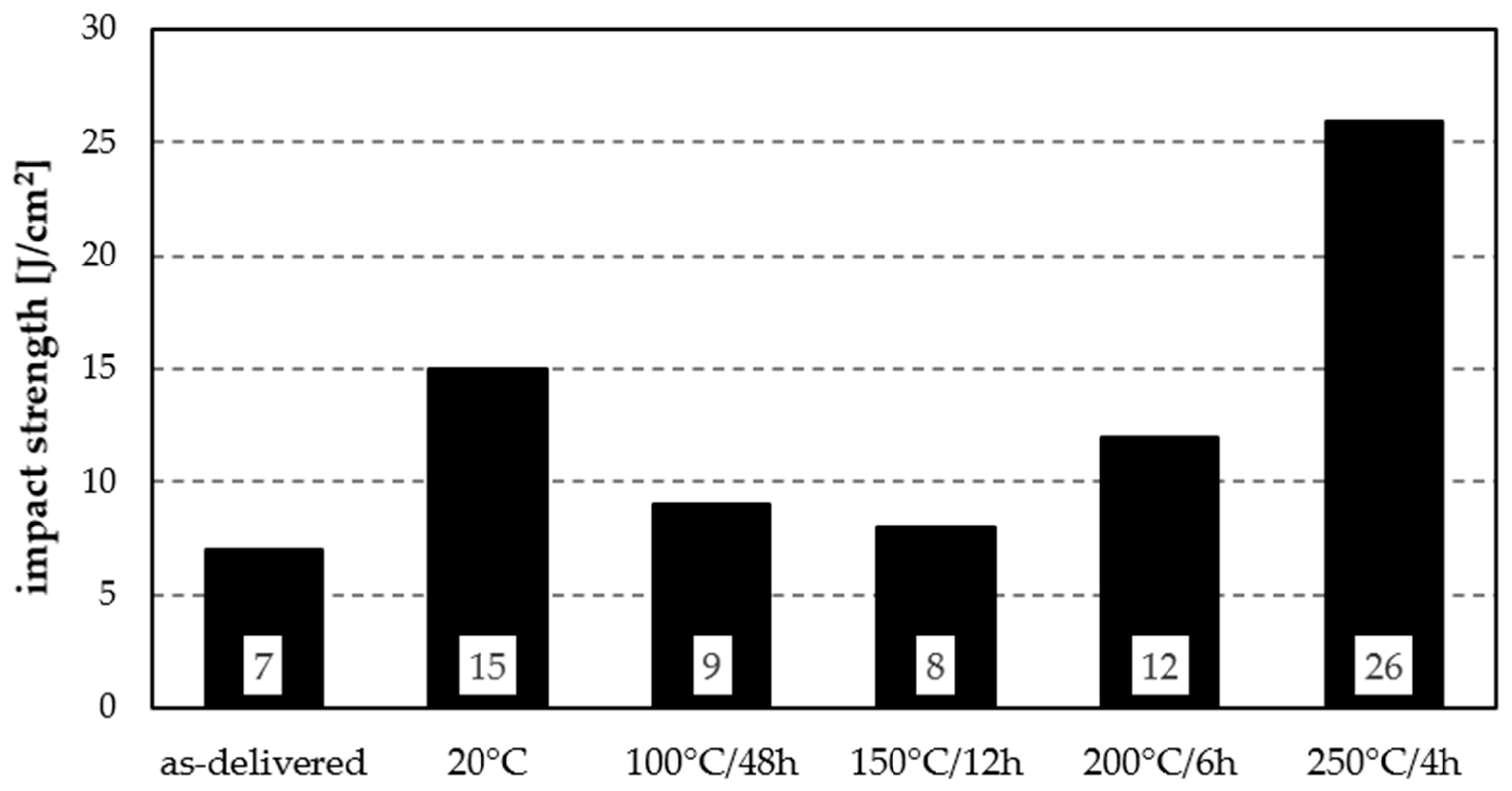

- Impact tests showed that moderate ageing conditions (100–150 °C) do not improve the material’s resistance to fracture, while higher temperatures lead to a significant increase in impact strength. The highest value—26 J/cm2—was obtained after ageing at 250 °C/4 h, representing nearly a fourfold increase compared with the as-delivered condition.

- The resistance to abrasive wear of the Al 7075 alloy increases with the ageing temperature. The lowest value of the kb coefficient (0.860) was obtained after natural ageing, and the highest (kb = 1.216) after heat treatment at 250 °C/4 h.

- An inverse correlation was found between hardness and resistance to abrasive wear—the samples with the highest hardness did not exhibit the most favourable wear-resistance indices. Impact strength and grain size proved to be more reliable criteria for predicting the tribological performance of the Al 7075 alloy, as confirmed by the high coefficients of determination (R2 = 0.8721 and R2 = 0.8735).

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zemlik, M.; Białobrzeska, B.; Tokłowicz, D. The Influence of Heat Treatment on the Mechanical Properties of AlMn1Cu Aluminium Alloy with One-Sided AlSi7.5 Cladding Used in Heat Exchangers. Materials 2025, 18, 3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.; Li, Y. Thermal Conductivity of Aluminum Alloys—A Review. Materials 2023, 16, 2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankauskas, V.; Žunda, A.; Katinas, A.; Tučkutė, S. Wear Study of Bulk Cargo Vehicle Body Materials Used to Transport Dolomite. Coatings 2025, 15, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roik, T.A.; Gavrysh, O.A.; Vitsiuk, I. Composite Antifriction Material Based on Wastes of Aluminum Alloy for Items of Post-Printing Equipment. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 2020, 59, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaleye, K.; Roik, T.; Kurzawa, A.; Gavrysh, O.; Pyka, D.; Bocian, M.; Jamroziak, K. Tribosynthesis of Friction Films and Their Influence on the Functional Properties of Copper-Based Antifriction Composites for Printing Machines. Mater. Sci.-Pol. 2022, 40, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemlik, M.; Roik, T.; Gavrish, O.; Jamroziak, K. Using Silumin Grinding Waste for New Self-Lubricating Antifriction Composites. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2025, 19, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, T.; Soutis, C. Recent Developments in Advanced Aircraft Aluminium Alloys. Mater. Design (1980–2015) 2014, 56, 862–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashjari, M.; Jodeiri Feizi, A. 7xxx Aluminum Alloys; Strengthening Mechanisms and Heat Treatment: A Review. Mater. Sci. Eng. Int. J. 2018, 2, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz, M.; Leśniewski, T.; Lachowicz, M. Effect of Dual-Stage Ageing and RRA Treatment on the Three-Body Abrasive Wear of the AW7075 Alloy. Stroj. Vestn.-J. Mech. Eng. 2022, 68, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzena, M. Lachowicz Metallurgical Aspects of the Corrosion Resistance of 7000 Series Aluminum Alloys—A Review. Mater. Sci. Pol. 2023, 41, 159–180. [Google Scholar]

- Leacock, A.G.; Howe, C.; Brown, D.; Lademo, O.-G.; Deering, A. Evolution of Mechanical Properties in a 7075 Al-Alloy Subject to Natural Ageing. Mater. Des. 2013, 49, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://asm.matweb.com/Search/Specificmaterial.Asp?Bassnum=ma7075t6 (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Ładak, A.; Cichoń, M.; Lachowicz, M. Evaluation of the Effect of Dual-Stage Aging and RRA on the Hardening and Corrosion Resistance of AW7075 Alloy. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2022, 3, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, R.; Chruścielski, G. Possibilities to Modify the Properties of the AW7075 Aluminum Alloy for the Automotive Industry. Combust. Engines 2024, 197, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 573-3:2019; Aluminium and Aluminium Alloys—Chemical Composition and Form of Wrought Products—Part 3: Chemical Composition and Form of Products. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Bao, J.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Yan, H. Influence of T6 Heat Treatment on the Microstructure and Tribological Properties of ADC12-GNPs Composites. Diam Relat Mater 2023, 140, 110497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevansuriya, R.; Sridhar, R.; Pugazhenthi, R. Study the Mechanical and Morphological Properties of Aluminium Alloy 7075 by Aging Treatments. Mater. Today Proc. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahi, A.; Hosseini-Toudeshky, H.; Ghalehbandi, S.M. Effect of Heat Treatment on Mechanical Properties of ECAPed 7075 Aluminum Alloy. Adv. Mat. Res. 2013, 829, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalehbandi, S.M.; Fallahi Arezoodar, A.; Hosseini-Toudeshky, H. Influence of Aging on Mechanical Properties of Equal Channel Angular Pressed Aluminum Alloy 7075. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. B J. Eng. Manuf. 2017, 231, 1803–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN ISO 643:2020; Steels—Micrographic Determination of the Apparent Grain Size. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- PN-EN ISO 6507:2007; Metallic Materials—Vickers Hardness Test. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2007.

- PN-EN ISO 148-1:2017-02; Metallic Materials—Charpy Pendulum Impact Test—Part 1: Test Method. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2017.

- GOST 23.208-79; Ensuring Wear Resistance of Products—Methods for Testing Materials for Abrasive Wear by Loose Abrasives. State Committee for Standards of the USSR: Moscow, Russia, 1979.

- ASTM G65; Standard Test Method for Measuring Abrasion Using the Dry Sand/Rubber Wheel Apparatus. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- PN-M-59115:1976; Metals—Method for Determination of Abrasive Wear Resistance. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 1976.

- Zemlik, M.; Konat, Ł.; Leśny, K.; Jamroziak, K. Comparison of Abrasive Wear Resistance of Hardox Steel and Hadfield Cast Steel. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyrzykowski, J.W.; Pleszakow, E.; Sieniawski, J. Deformation and Cracking of Metals; Publishing House “WNT”: Warsaw, Poland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Napiórkowski, J.; Lemecha, M.; Konat, Ł. Forecasting the Wear of Operating Parts in an Abrasive Soil Mass Using the Holm-Archard Model. Materials 2019, 12, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, B.P.; Lopes, M.M.; Garcia, A.; dos Santos, C.A. The Correlation of Microstructure Features, Dry Sliding Wear Behavior, Hardness and Tensile Properties of Al-2wt%Mg-Zn Alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 764, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, M.; Özyürek, D.; Gürü, M. The Effects of Precipitate Size on the Hardness and Wear Behaviors of Aged 7075 Aluminum Alloys Produced by Powder Metallurgy Route. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2016, 41, 4273–4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodinger, T.; Lukšić, H.; Ćorić, D.; Rede, V. Abrasion Wear Resistance of Precipitation-Hardened Al-Zn-Mg Alloy. Materials 2024, 17, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Harsha, A.; Goyal, H.; Hussain, A.A.; Wesley, S. Three-Body Abrasive Wear Behaviour of Aluminium Alloys. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J. J. Eng. Tribol. 2013, 227, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axén, N.; Alahelisten, A.; Jacobson, S. Abrasive Wear of Alumina Fibre-Reinforced Aluminium. Wear 1994, 173, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elleuch, K.; Mezlini, S.; Guermazi, N.; Kapsa, P. Abrasive Wear of Aluminium Alloys Rubbed against Sand. Wear 2006, 261, 1316–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemlik, M.; Białobrzeska, B.; Konat, Ł. The Effect of Grain Size on the Mechanical Properties and Abrasion Resistance of High-Strength Hardox Extreme Steel. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2025, 19, 214–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isadare, A.D.; Aremo, B.; Adeoye, M.O.; Olawale, O.J.; Shittu, M.D. Effect of Heat Treatment on Some Mechanical Properties of 7075 Aluminium Alloy. Mater. Res. 2012, 16, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| %Al | %Zn | %Mg | %Cu | %Fe | %Si | %Mn | %Cr | %Zr | %Ti | % Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EN-573:3 2019 | ||||||||||

| Remainder | 5.1–6.1 | 2.1–2.9 | 1.2–2.0 | Max 0.5 | Max 0.4 | Max 0.3 | 0.18–0.28 | Max 0.25 | Max 0.20 | Max 0.05 |

| AA7075 | ||||||||||

| 89.7 | 5.7 | 2.74 | 1.47 | 0.15 | - | 0.0039 | 0.202 | - | 0.0307 | 0.0034 |

| No | Solution Treatment | Ageing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature [°C] | Time [h] | ||

| 1 | 480 °C/1 h | 100 | 48 |

| 2 | 150 | 12 | |

| 3 | 200 | 6 | |

| 4 | 250 | 4 | |

| State of Heat Treatment | Actual Mass Consumption (g) | Actual Volumetric Wear Loss Iexp (m3) | Wear Coefficient k Determined Empirically | Wear Coefficient k Used in the Archard Wear Model | Theoretical Volumetric Wear Loss IZ (m3) | Relative Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| as-delivered | 0.131 | 4.69 × 108 | 0.00643 | 0.00571 | 4.16 × 108 | −11.2 |

| 20 °C | 0.153 | 5.45 × 108 | 0.00705 | 4.42 × 108 | −19.0 | |

| 100 °C | 0.145 | 5.18 × 108 | 0.00772 | 3.83 × 108 | −26.0 | |

| 150 °C | 0.122 | 4.37 × 108 | 0.00603 | 4.14 × 108 | −5.21 | |

| 200 °C | 0.116 | 4.13 × 108 | 0.00446 | 5.29 × 108 | 28 | |

| 250 °C | 0.108 | 3.86 × 108 | 0.00258 | 8.52 × 108 | 121 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Papież, J.; Leśny, K.; Zemlik, M. The Effect of Ageing on the Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Al-Zn-Mg Alloy. Materials 2026, 19, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010104

Papież J, Leśny K, Zemlik M. The Effect of Ageing on the Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Al-Zn-Mg Alloy. Materials. 2026; 19(1):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010104

Chicago/Turabian StylePapież, Jakub, Kacper Leśny, and Martyna Zemlik. 2026. "The Effect of Ageing on the Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Al-Zn-Mg Alloy" Materials 19, no. 1: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010104

APA StylePapież, J., Leśny, K., & Zemlik, M. (2026). The Effect of Ageing on the Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Al-Zn-Mg Alloy. Materials, 19(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010104