Optimization of Mechanical Properties of Multiphase Materials with Auxetic Phase

Abstract

1. Introduction

- For ν > 0, the body elongates in the direction of tension and shrinks laterally. This is the most common behavior observed in conventional materials.

- For ν < 0, the body both elongates in the direction of tension and expands laterally. This counter-intuitive behavior is referred to as “auxetic”.

- For ν = 0, a special case, the body only elongates in the direction of tension and its lateral dimensions do not change. An example of natural material with near-zero Poisson’s ratio is cork [2].

2. Materials and Methods

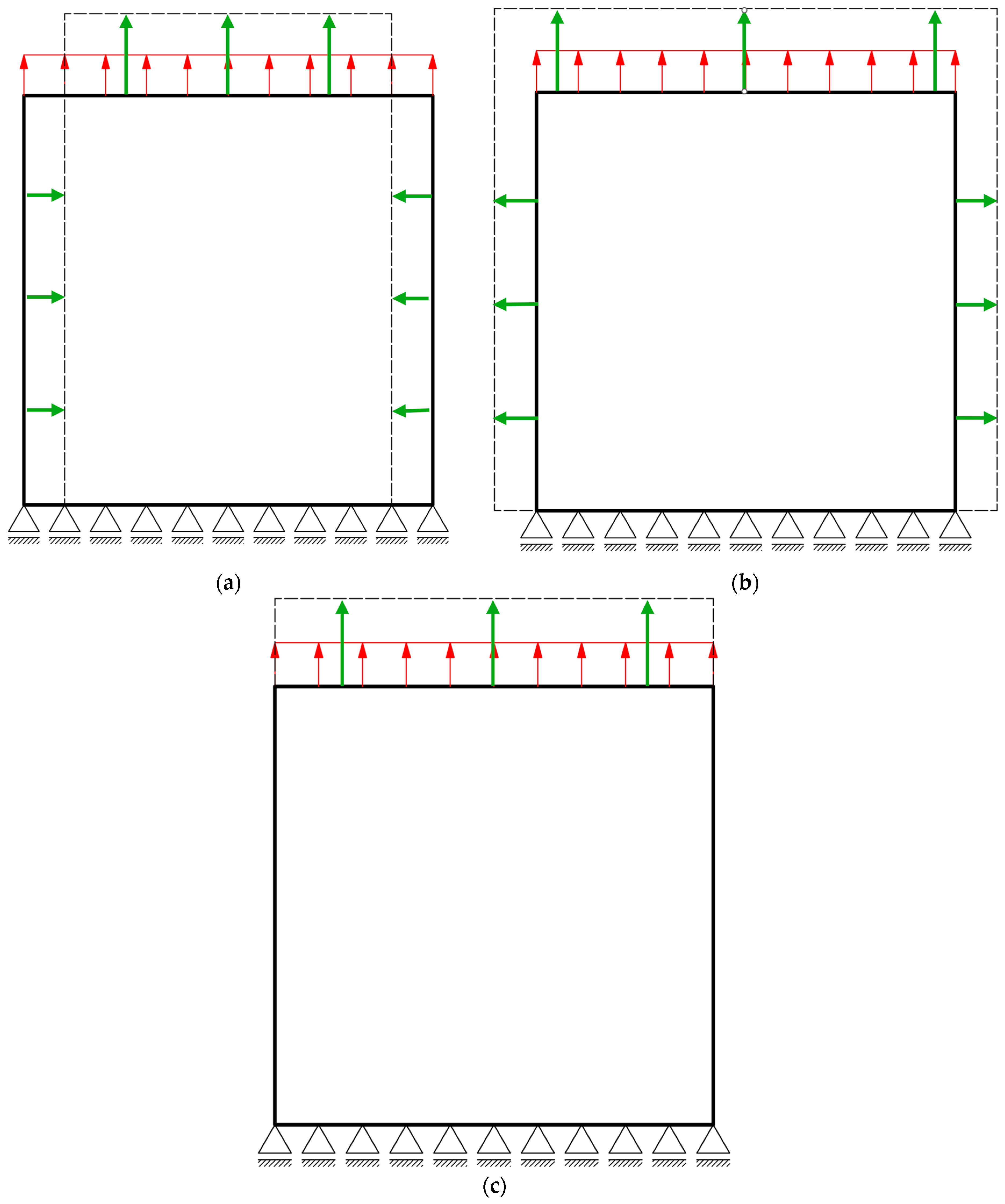

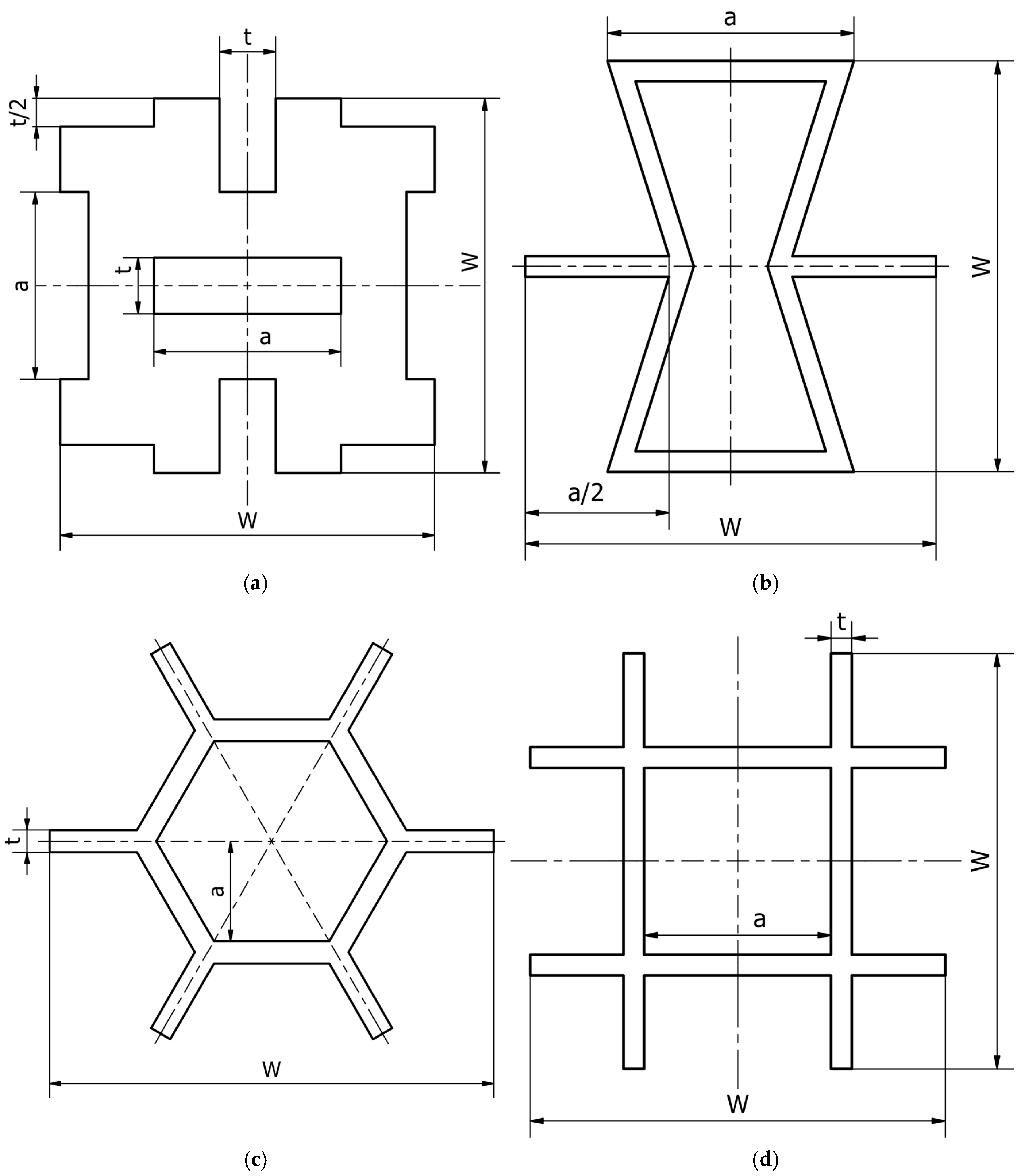

2.1. Multiscale Modeling

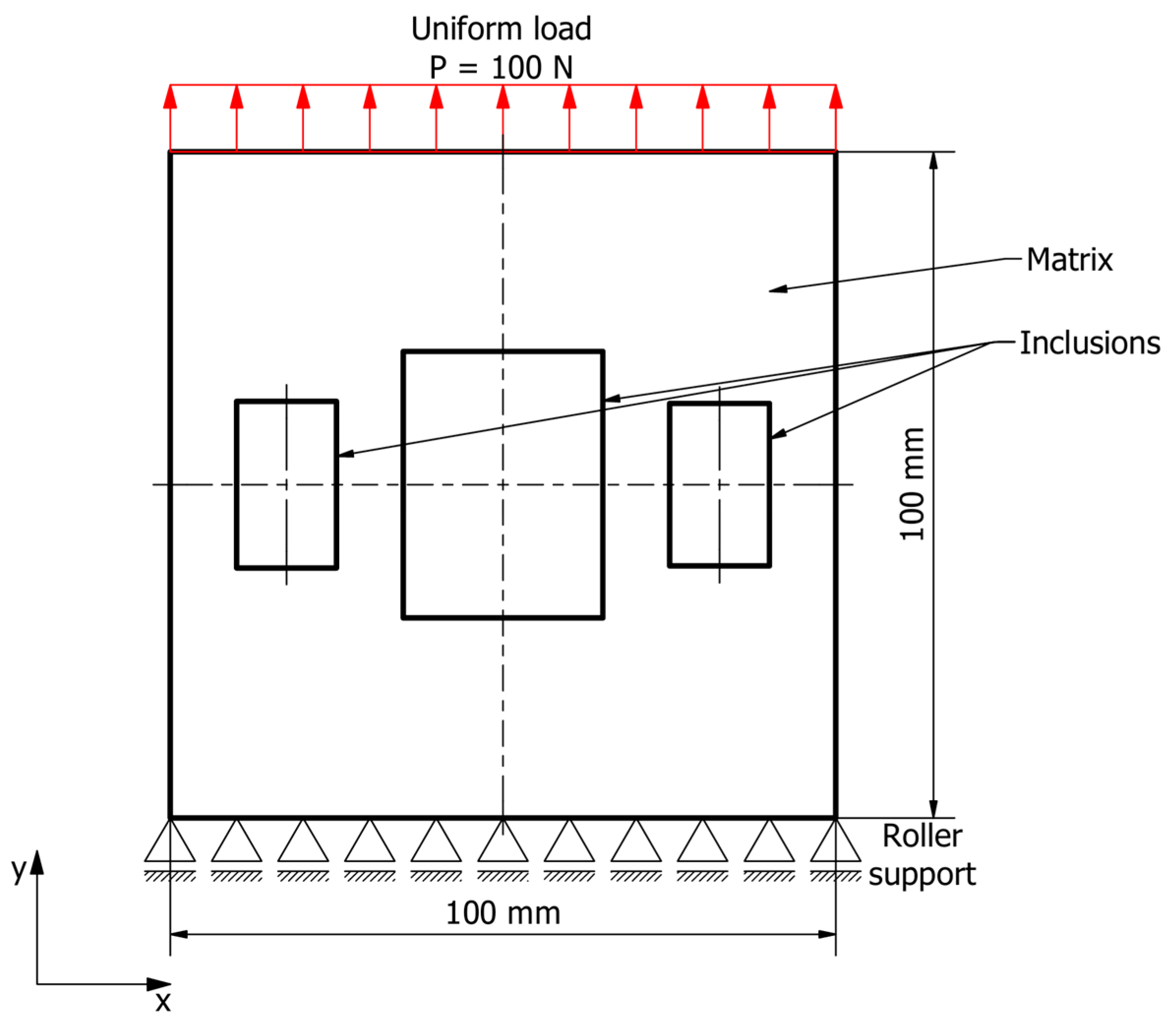

2.2. Multiphase Material

2.3. Optimization

- Number of initial samples—6000

- Number of samples per iteration—1200

- Maximum allowable Pareto percentage—70

- Convergence stability percentage—2

- Maximum number of iterations—20

- Maximum number of candidates—20

3. Results

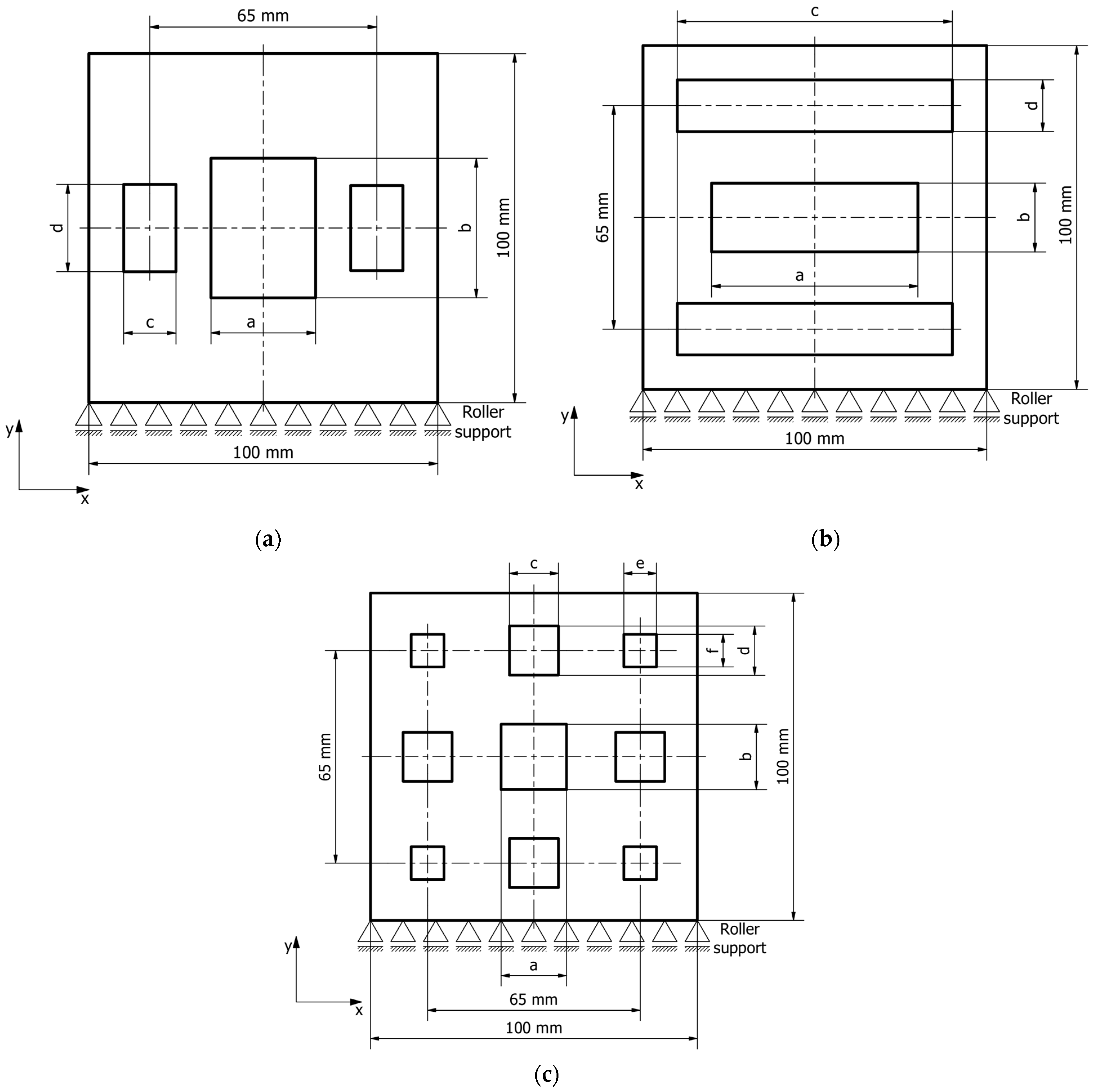

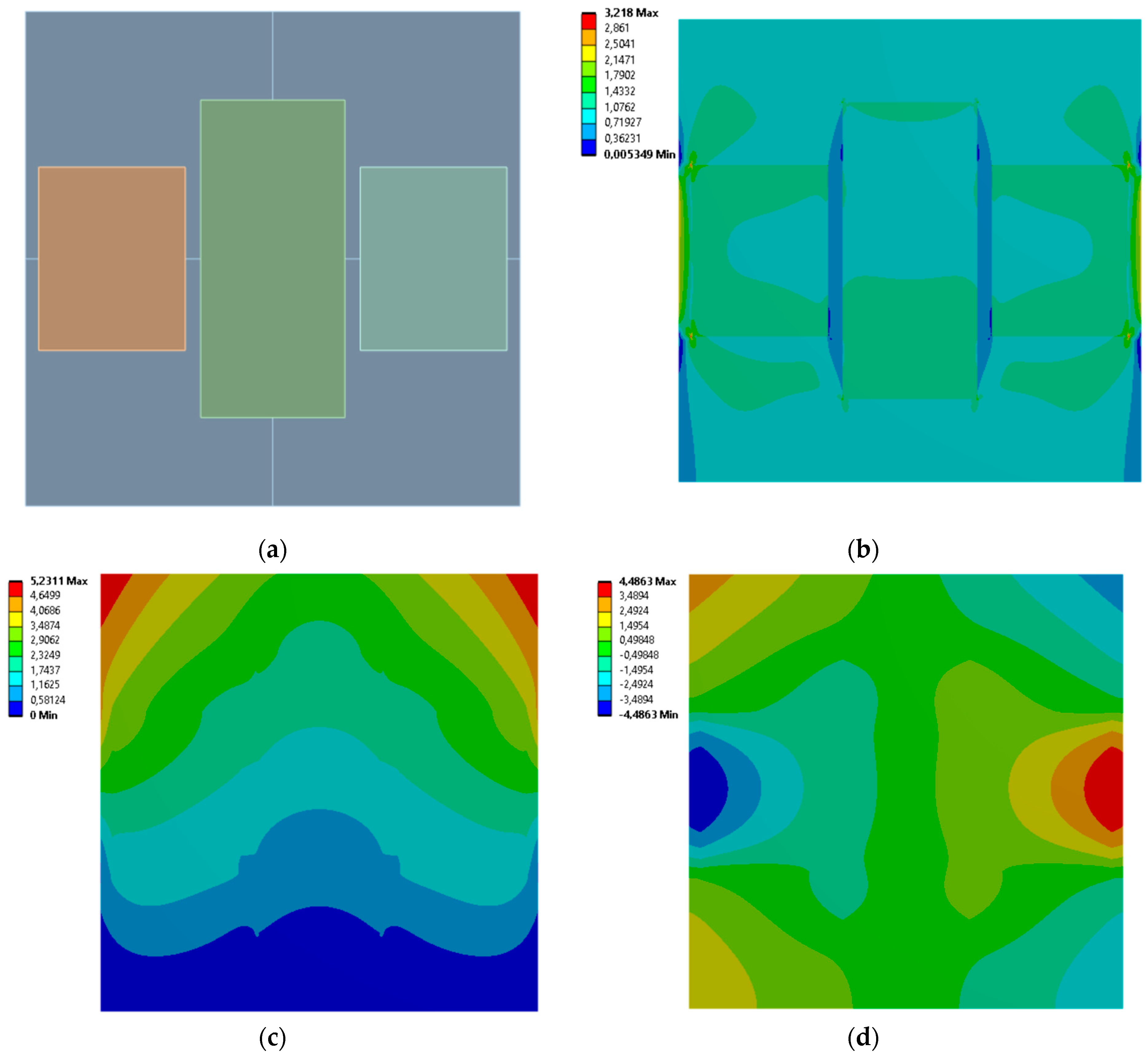

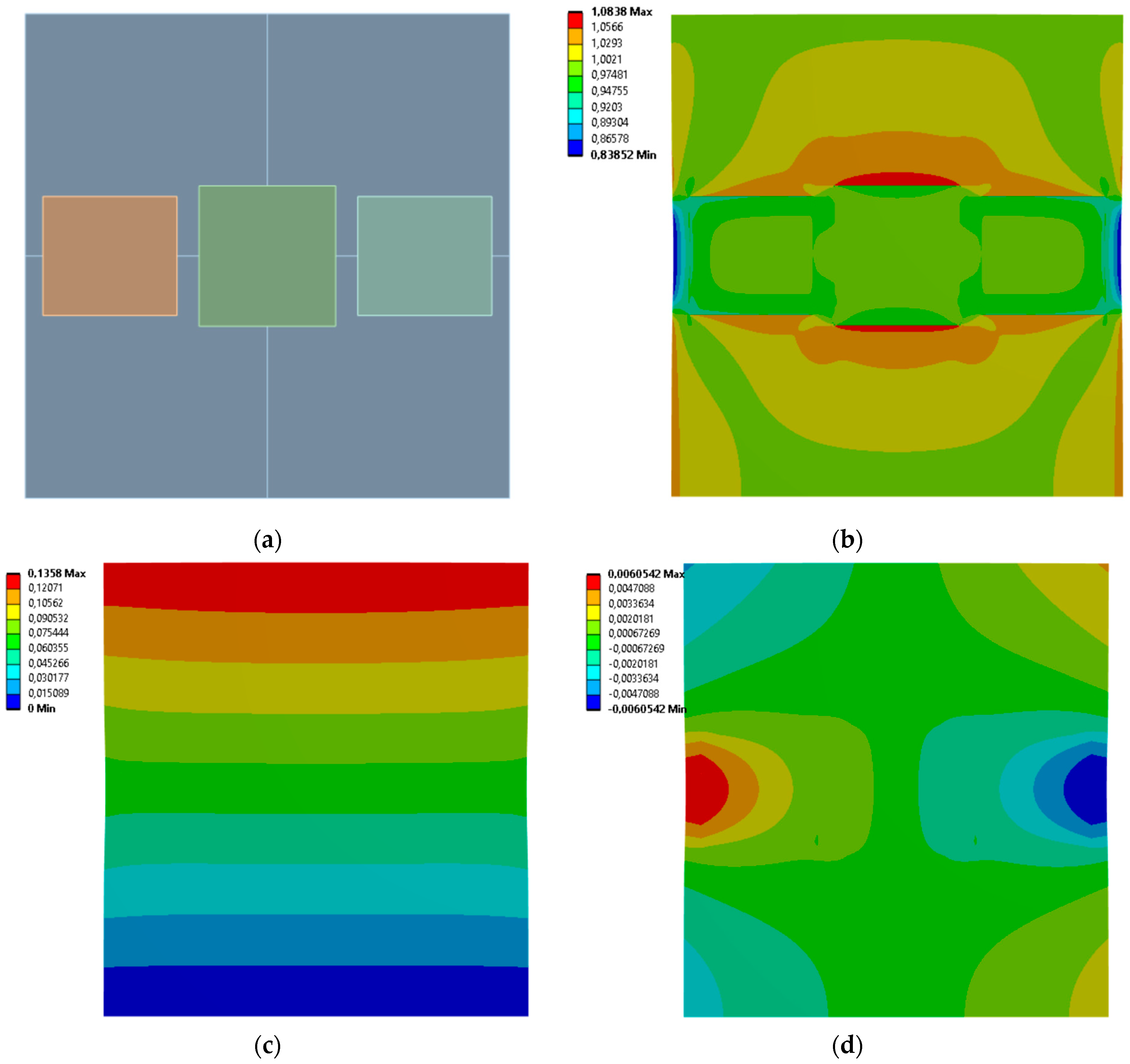

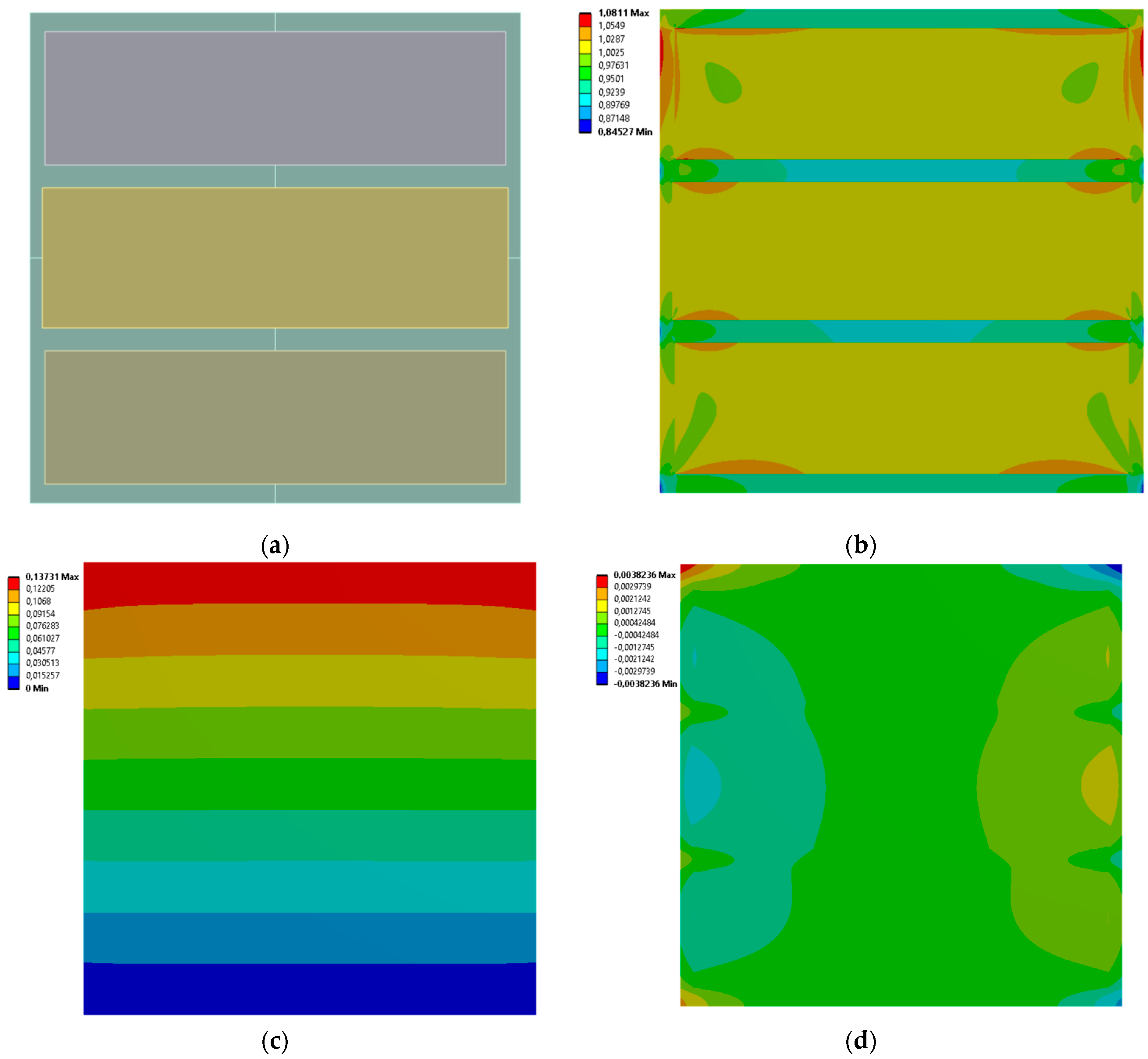

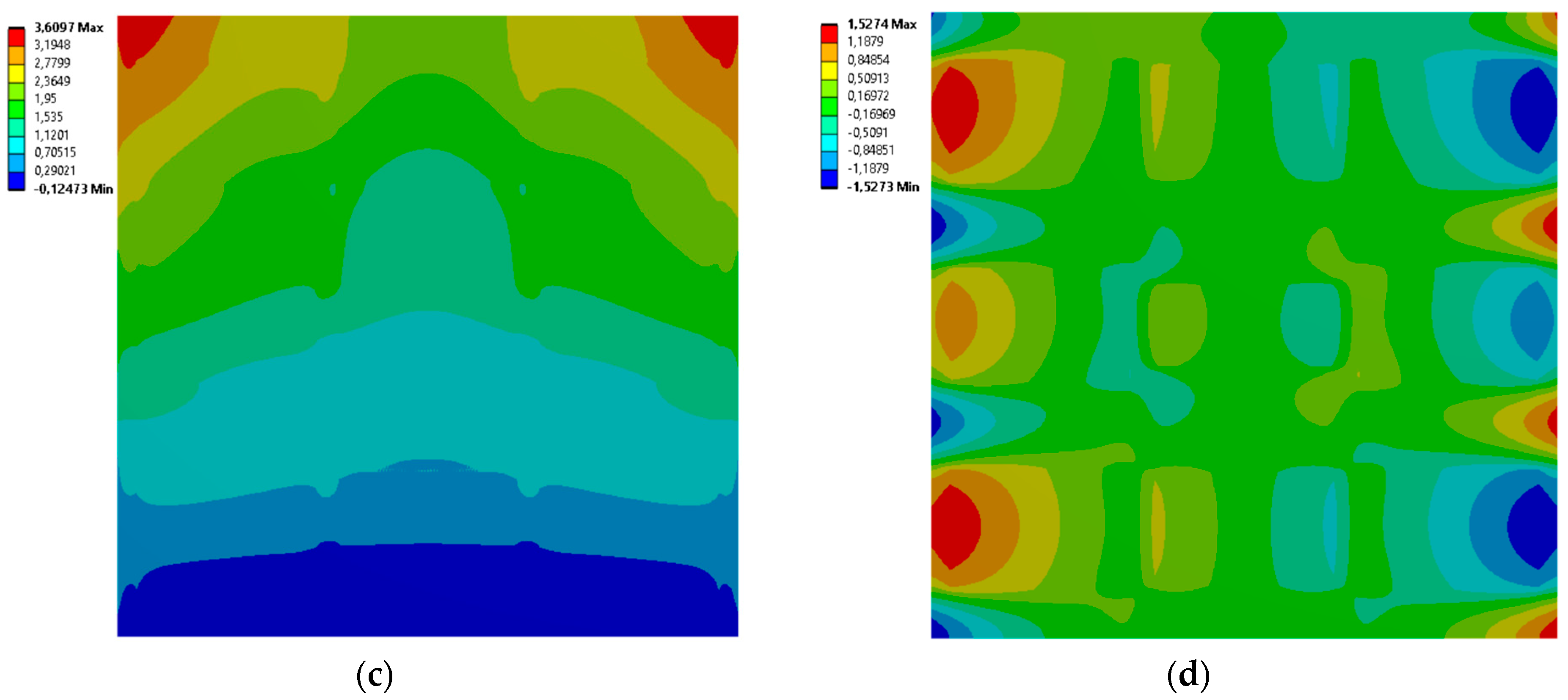

3.1. 3 Vertical Rectangles

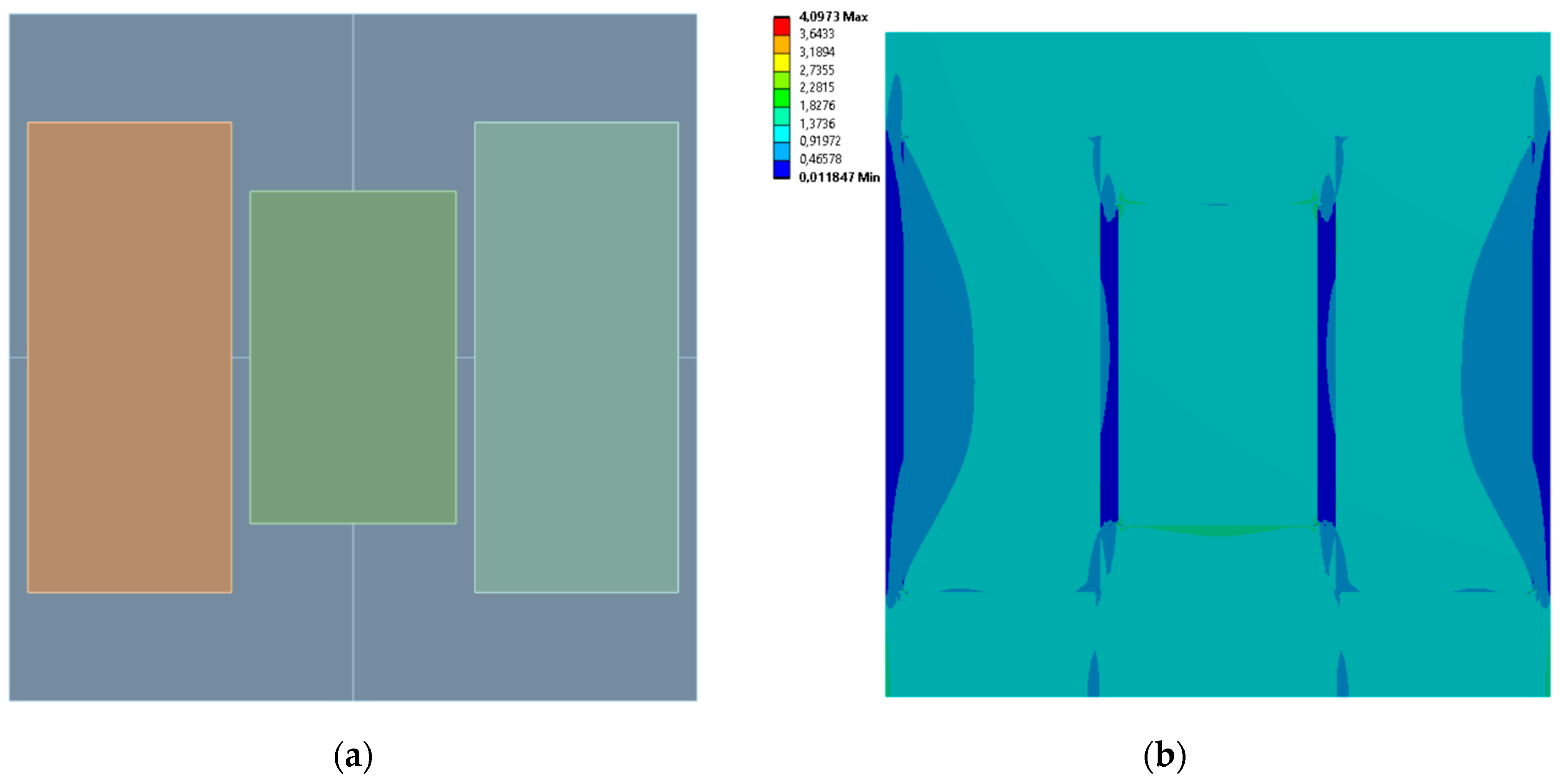

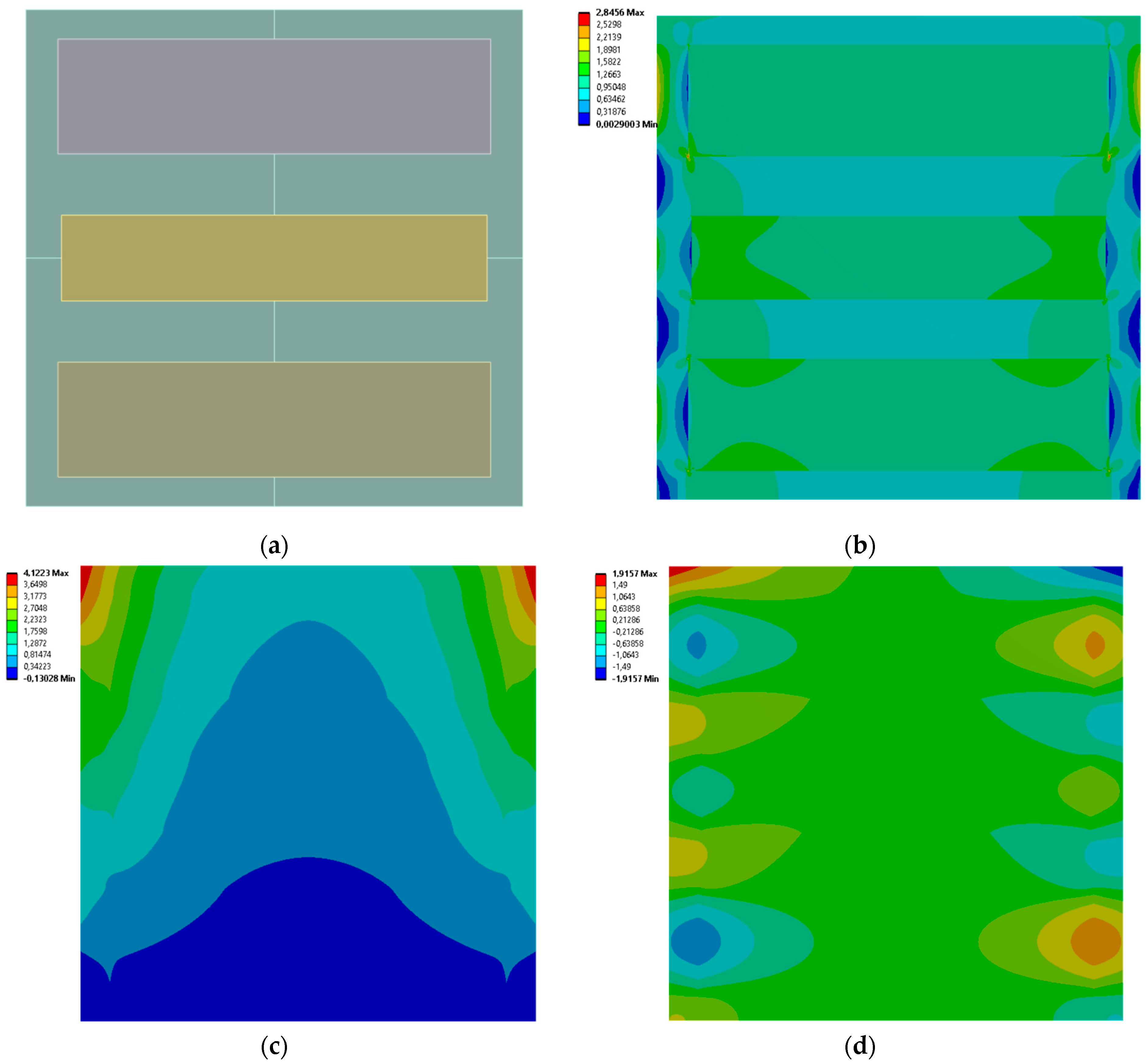

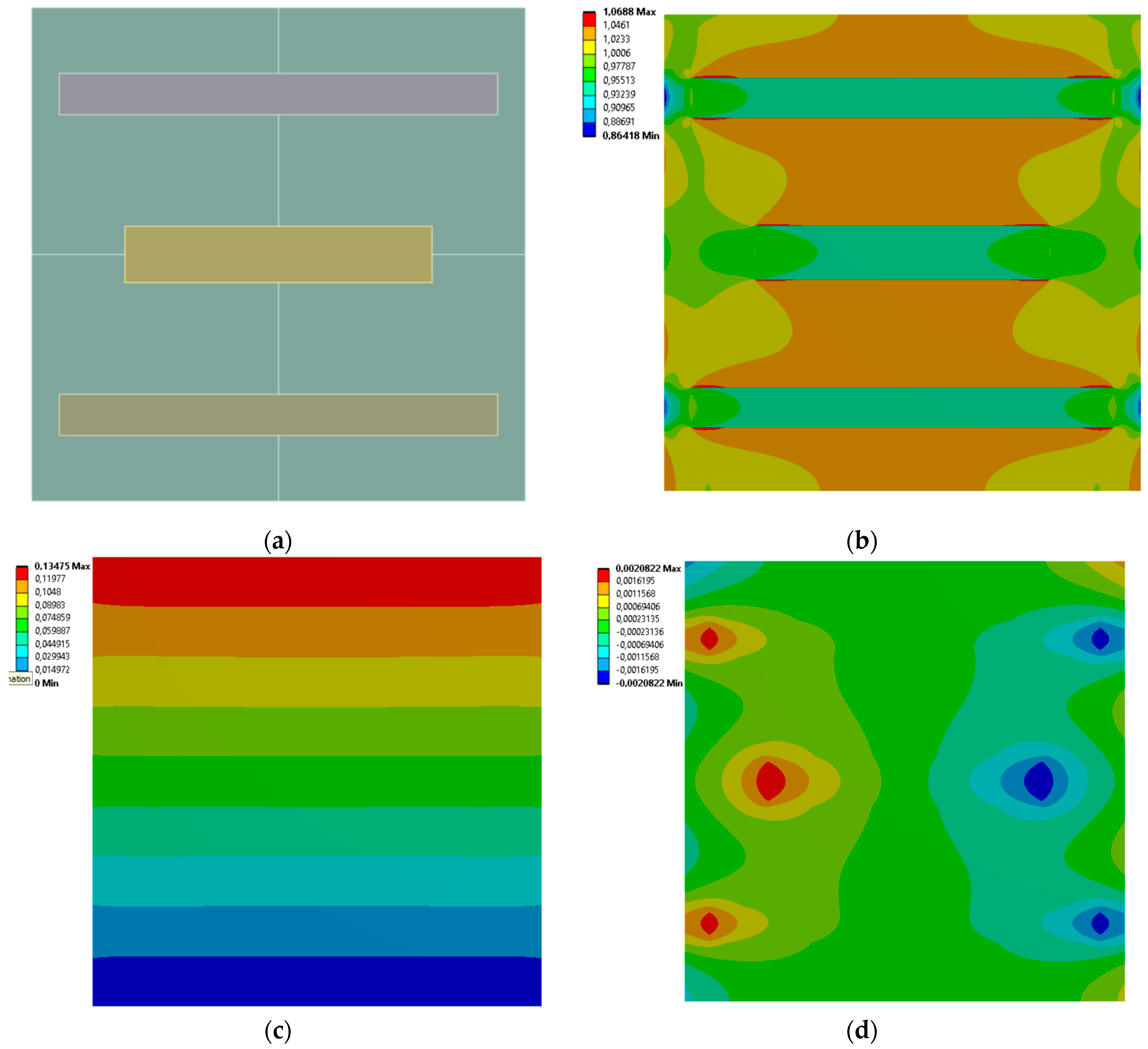

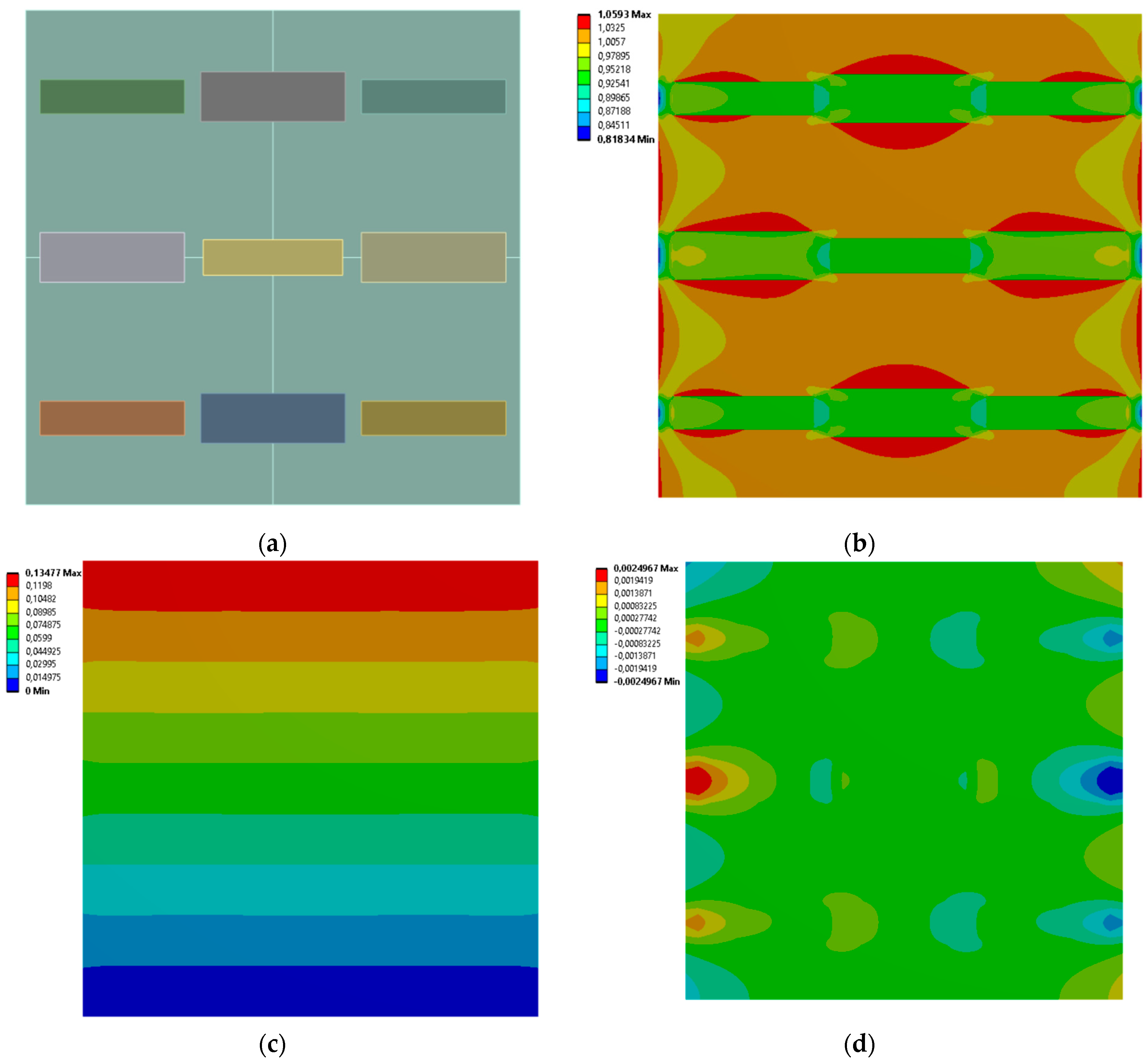

3.2. 3 Horizontal Rectangles

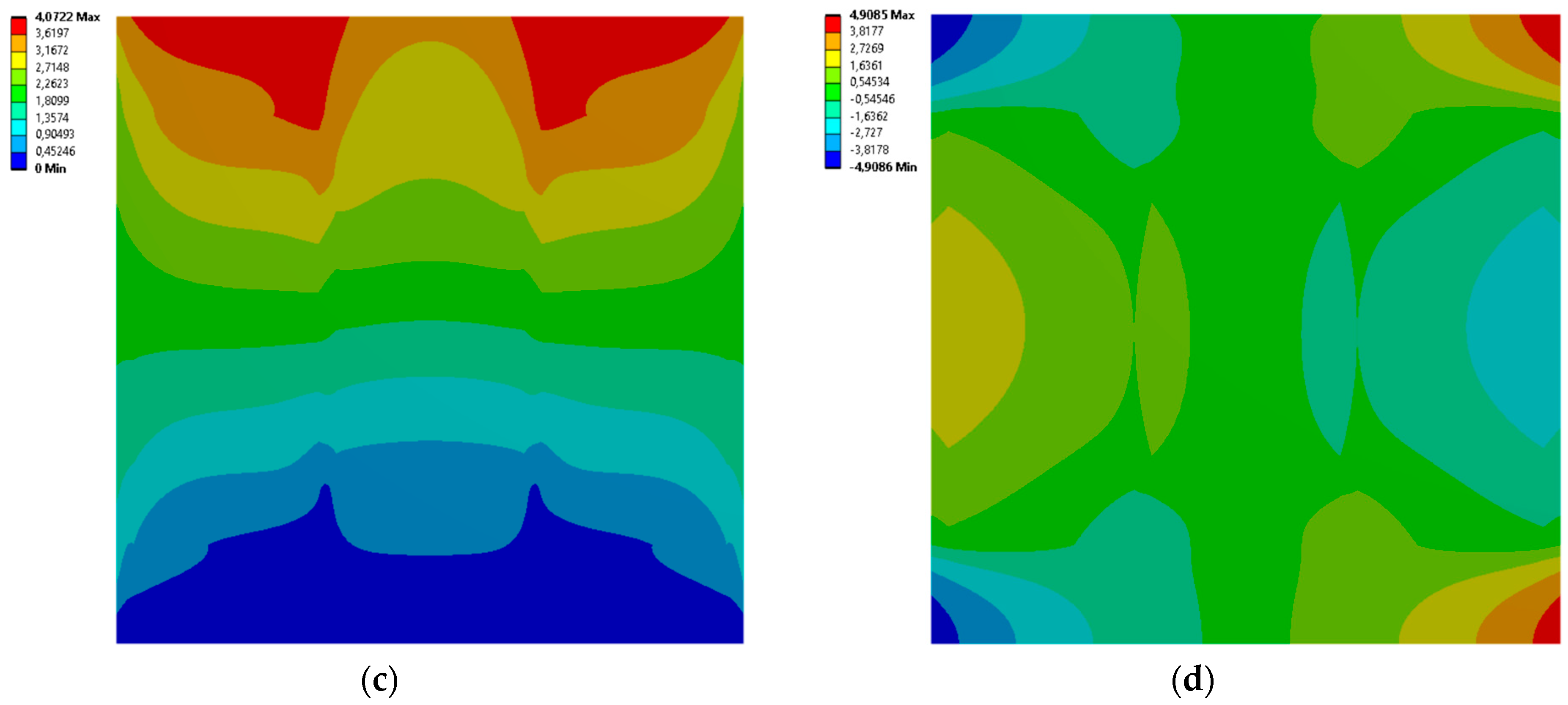

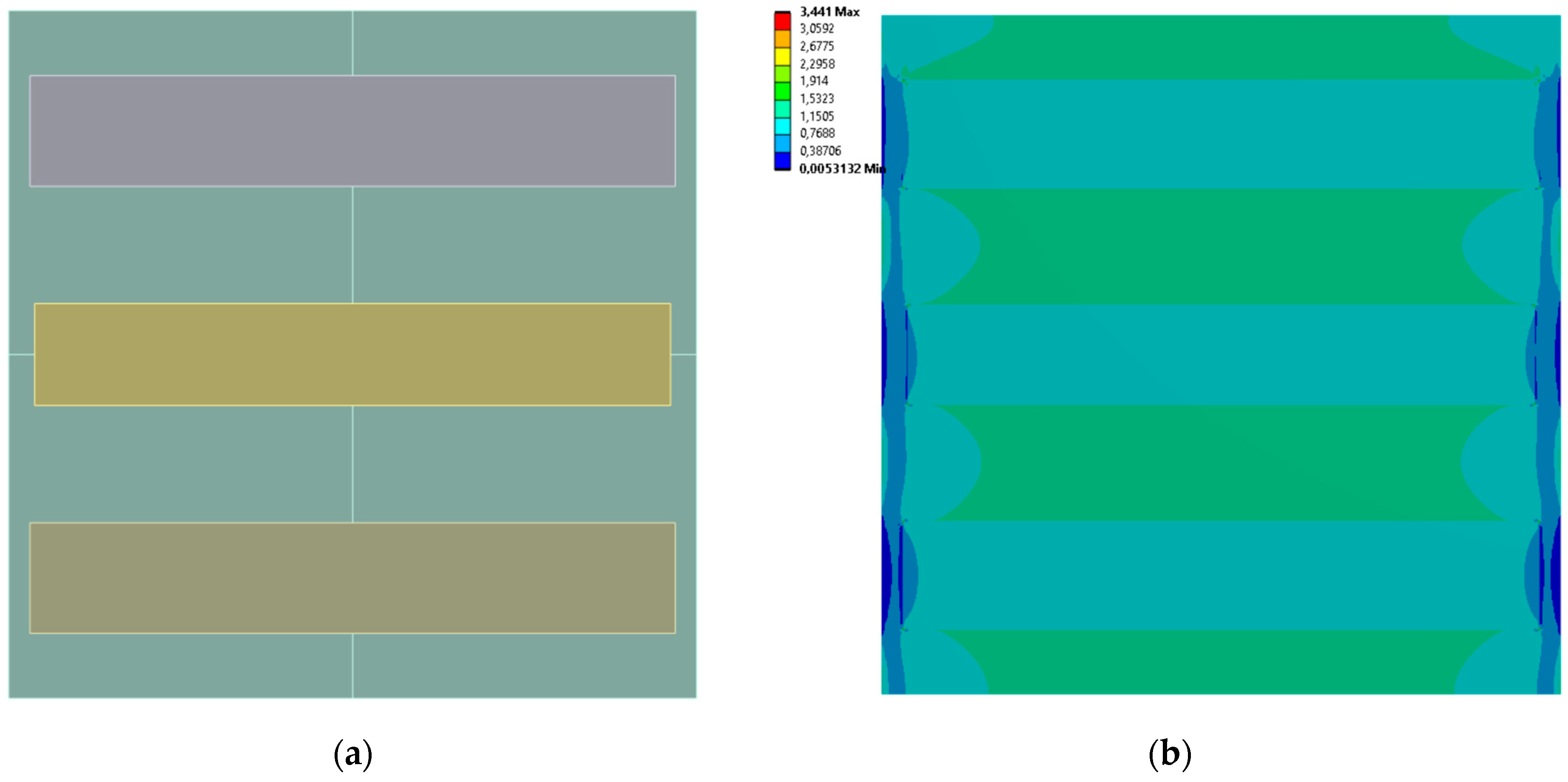

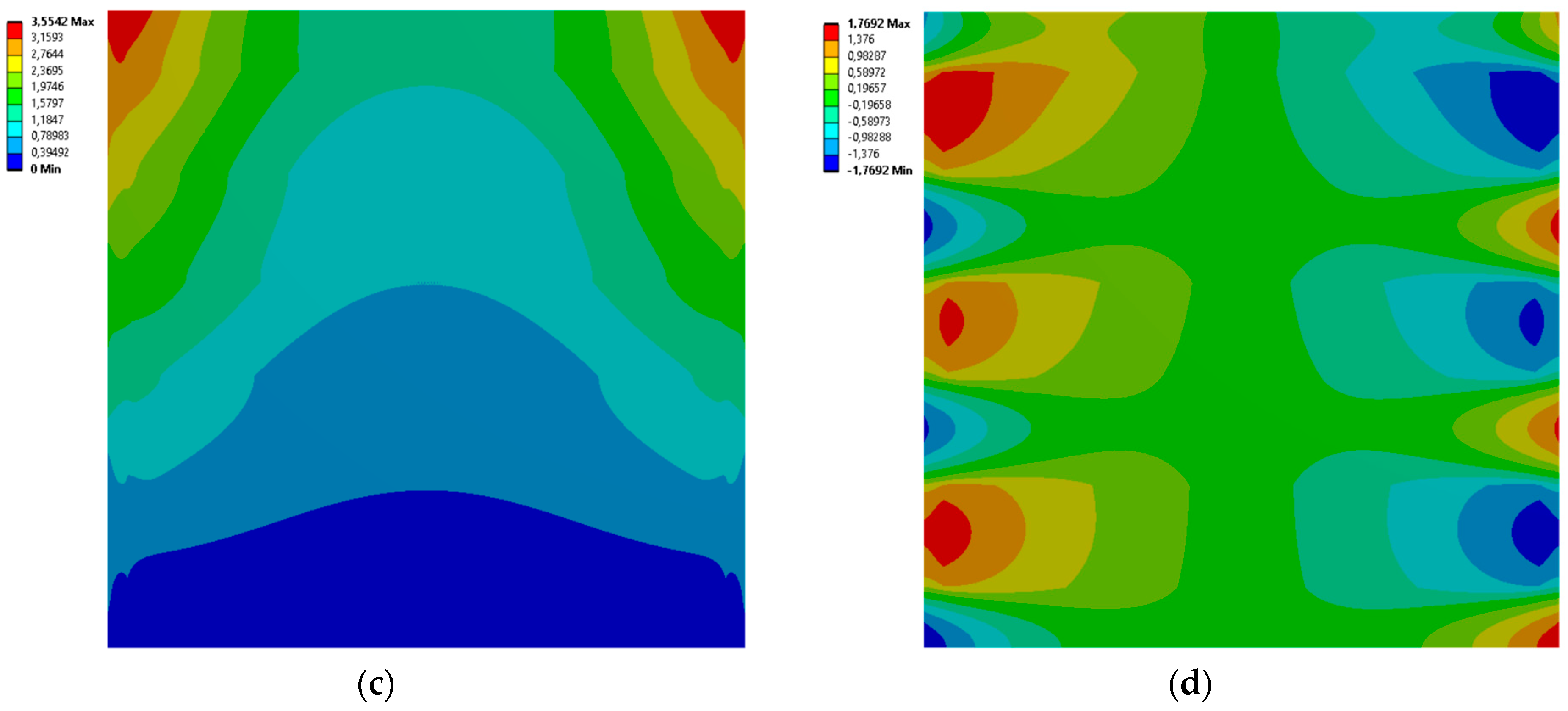

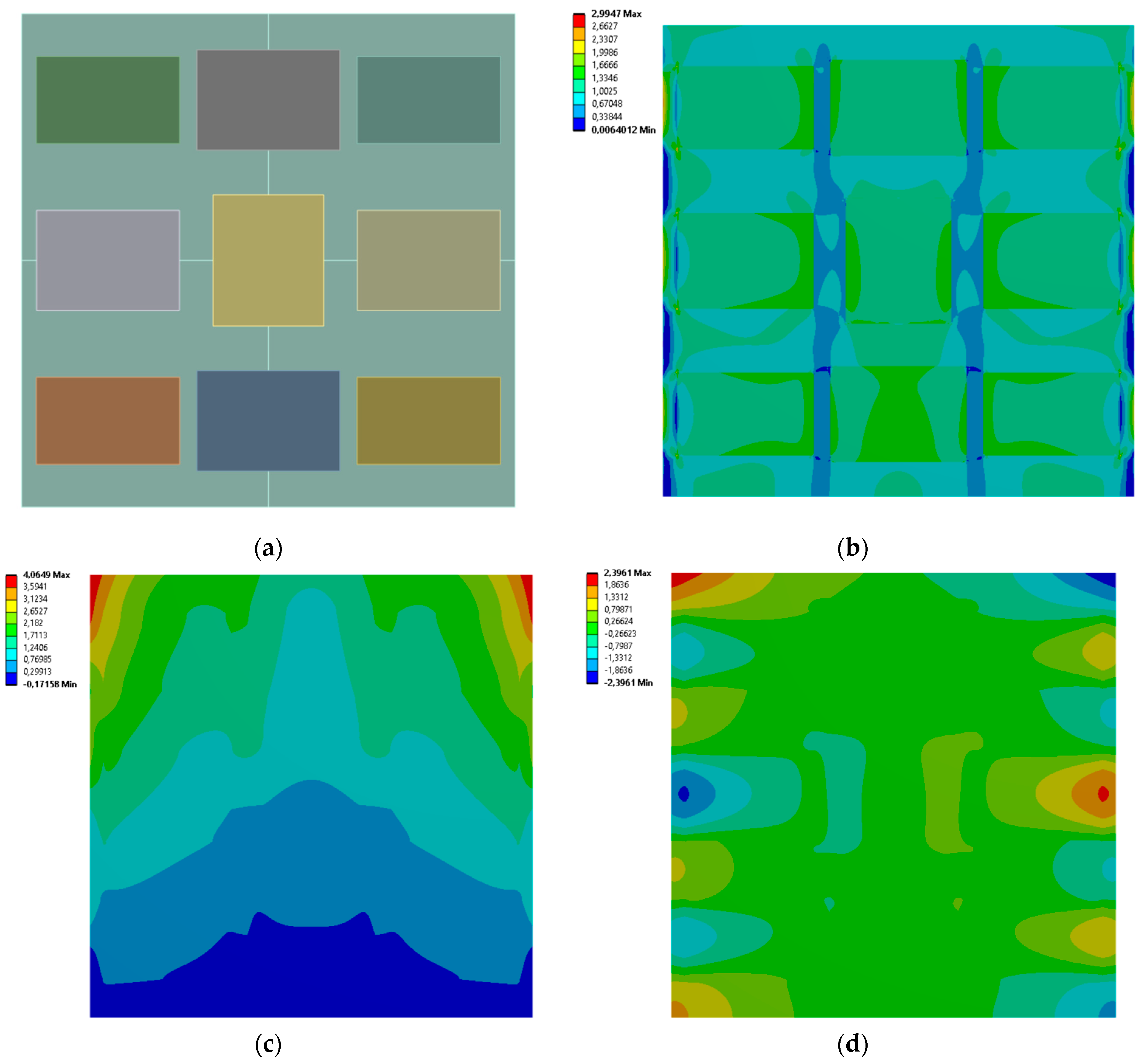

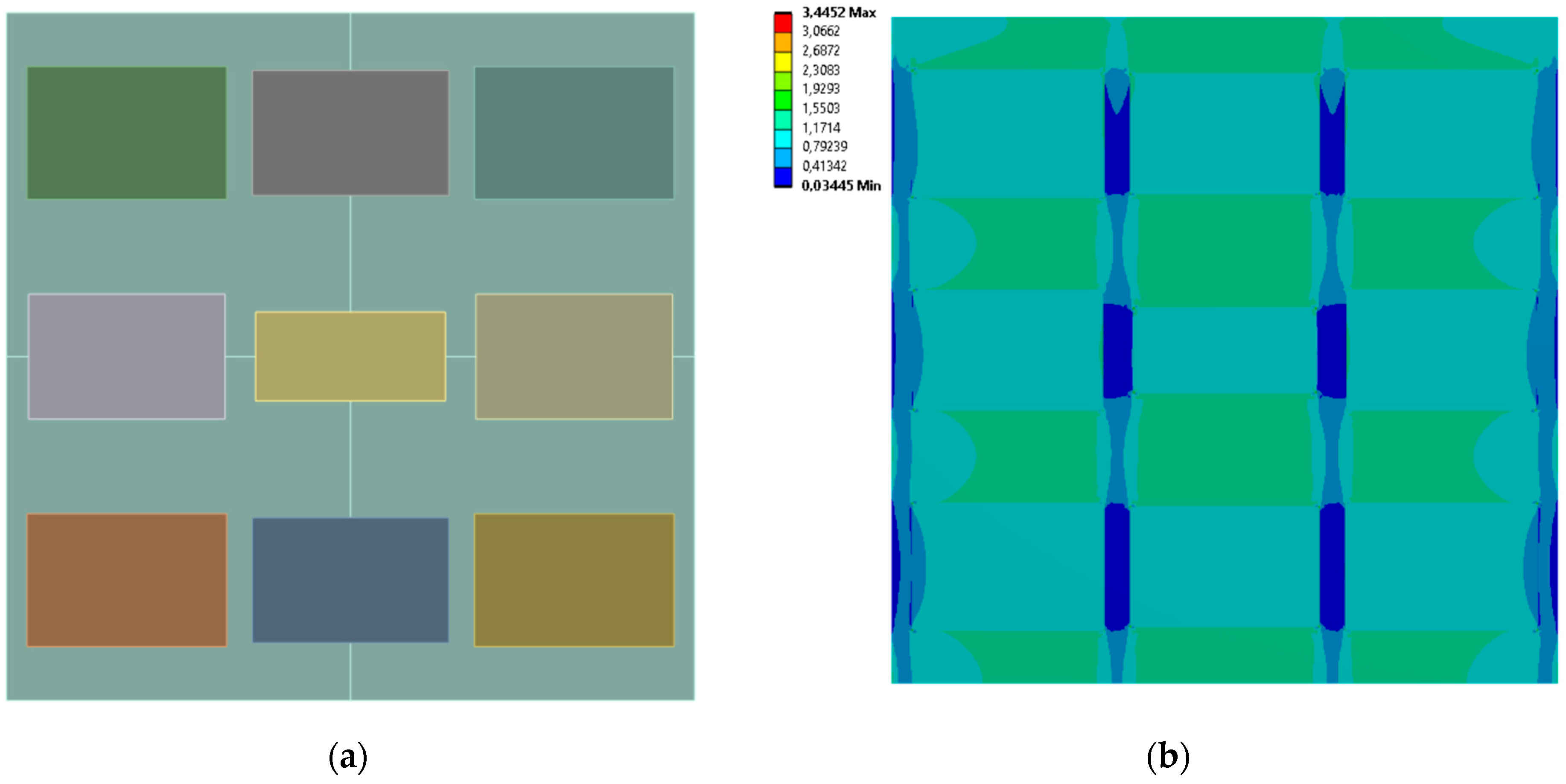

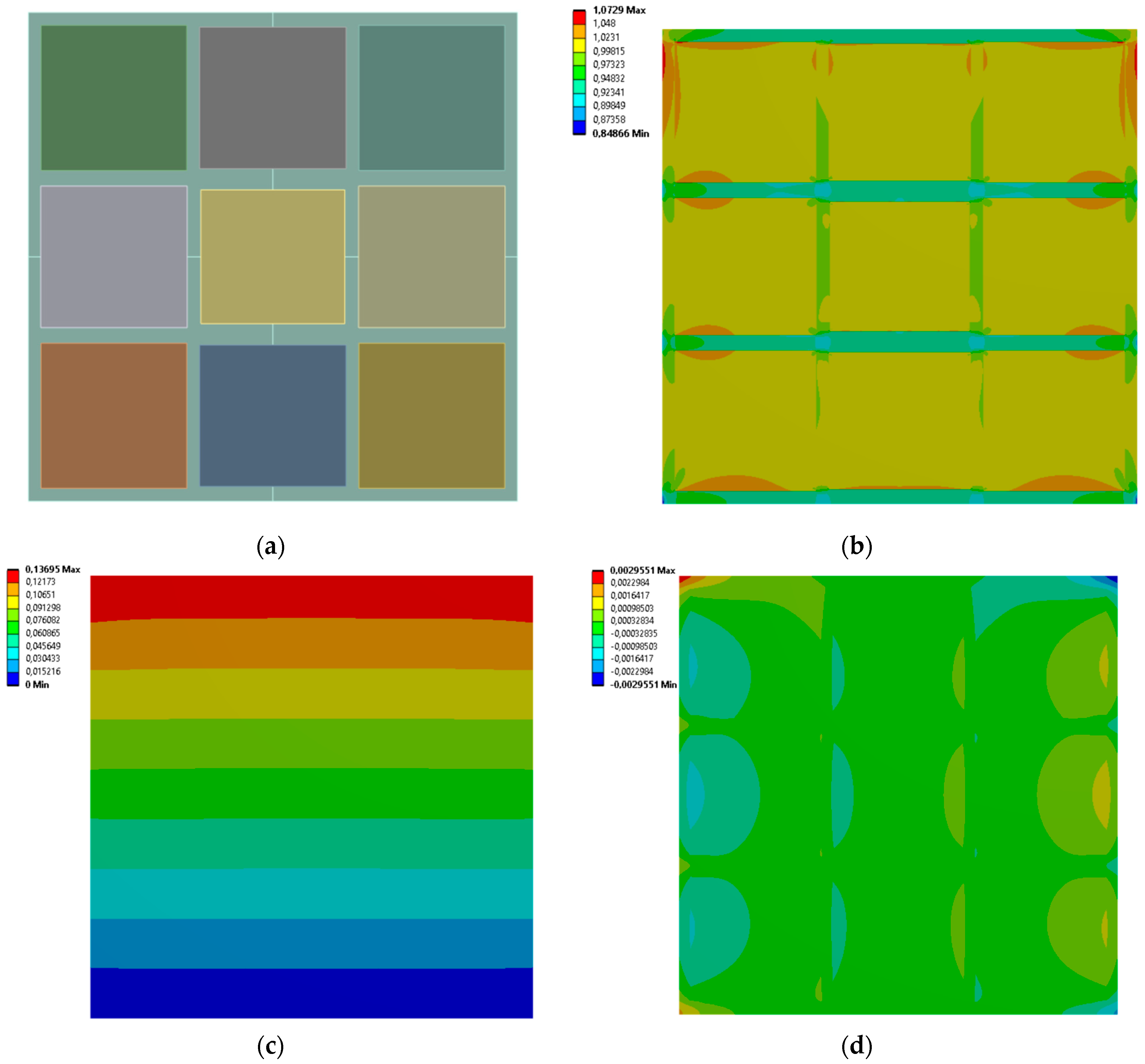

3.3. 9 Rectangles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Evans, K.E. Auxetic polymers: A new range of materials. Endeavour 1991, 15, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortes, M.A.; Teresa Nogueira, M. The poison effect in cork. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1989, 122, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, A.E. A Treatise on the Mathematical Theory of Elasticity, 4th ed; Cambridge University Press: Dover, NY, USA, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Voigt, W. Lehrbuch der Kristallphysik; Teubner Verlag: Leipzig, Germany, 1928. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Bhullar, S.K. Three decades of auxetic polymers: A review. e-Polymers 2015, 15, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.C. Auxetic Materials and Structures; Springer: Singapore, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.E.; Alderson, A. Auxetic materials: Functional materials and structures from lateral thinking! Adv. Mater. 2000, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elipe, J.C.A.; Lantada, A.D. Comparative study of auxetic geometries by means of computer-aided design and engineering. Smart Mater. Struct. 2012, 21, 105004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Aznar, J.M.; Nasello, G.; Hervas-Raluy, S.; Pérez, M.A.; Gómez-Benito, M.J. Multiscale modeling of bone tissue mechanobiology. Bone 2021, 151, 116032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstemeyer, M.F. Multiscale modeling: A review. In Practical Aspects of Computational Chemistry; Leszczynski, J., Shukla, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, K.; Singamneni, S. A new auxetic structure with significantly reduced stress concentration effects. Mater. Des. 2019, 173, 107779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Seo, D.; Kim, D.N. Mechanics of auxetic materials. In Handbook of Mechanics of Materials; Schmauder, S., Chen, C.S., Chawla, K., Chawla, N., Chen, W., Kagawa, Y., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Hulbert, G.H. Crashworthiness analysis and collaborative optimization design for a novel crash-box with re-entrant auxetic core. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2020, 62, 2167–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Shen, J.; Tran, P.; Ngo, T.D.; Xie, Y.M. Auxetic nail: Design and experimental study. Compos. Struct. 2018, 184, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momoh, E.O.; Jayasinghe, A.; Hajsadeghi, M.; Vinai, R.; Evans, K.E.; Kripakaran, P.; Orr, J. A state-of-the-art review on the application of auxetic materials in cementitious composites. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 196, 111447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Lu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Liao, W.-H.; Yin, G.; Li, J.; Xiao, F.; Qiu, R. Enhancing the output performance of energy harvesters using hierarchical auxetic structure and optimization techniques. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 71, 11641–11649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohar, S.; Hussain, G.; Ilyas, M.; Ali, A. Performance of 3D printed topologically optimized novel auxetic structures under compressive loading: Experimental and FE analyses. J. Mark. Res. 2021, 15, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behinfar, P.; Nourani, A. Analytical and numerical solution and multi-objective optimization of tetra-star-chiral auxetic stents. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruggi, M.; Zega, V.; Corigliano, A. Optimization of auxetic structures for MEMS applications. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Thermal, Mechanical and Multi-Physics Simulation and Experiments in Microelectronics and Microsystems (EuroSimE), Montpellier, France, 17–20 April 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.P.; Poh, L.H.; Zhu, Y.; Dirrenberger, J.; Forest, S. Systematic design of tetra-petals auxetic structures with stiffness constraint. Mater. Des. 2019, 170, 107669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Sun, S.; Zhang, T.Y. Machine learning accelerated design of auxetic structures. Mater. Des. 2023, 234, 112334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; He, Z.; Li, E.; Cheng, A.; Chen, T.; Tan, X.; Li, Q.; Xu, B. Crashworthiness design and multi-objective optimization of a novel auxetic hierarchical honeycomb crash box. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2021, 64, 2009–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, N.; Nowak, M.; Vesenjak, M.; Ren, Z. Structural optimization of the novel 3D graded axisymmetric chiral auxetic structure. Phys. Status Solidi B 2022, 259, 2200409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, T.; Li, R.; Mavrikos, S.; Blankenship, B.; Vangelatos, Z.; Yildizdag, M.E.; Grigoropoulos, C.P. Obtaining auxetic and isotropic metamaterials in counterintuitive design spaces: An automated optimization approach and experimental characterization. Comput. Mater. 2024, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, M.F.; Bréchet, Y.J.M. Designing hybrid materials. Acta Mater. 2003, 51, 5801–5821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kromm, F.X.; Quenisset, J.M.; Harry, R.; Lorriot, T. An example of multimaterials design. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2002, 4, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, K.; Du, X.; Xu, S.; Xie, Y.M. Maximizing the effective young’s modulus of a composite material by exploiting the Poisson effect. Compos. Struct. 2016, 153, 596–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawistowski, M.; Poteralski, A. Parametric optimization of selected auxetic structures. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 2024, 7, 4777–4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawistowski, M.; Poteralski, A. Development of a hybrid material with auxetic phase. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 2024, 7, 4767–4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.J.; Carter, F.; Jowers, I.; Moat, R.J. An isotropic zero Poisson’s ratio metamaterial based on the aperiodic ‘hat’ monotile. Appl. Mater. Today 2023, 35, 101959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimolai, G.; Qin, Q.; Mageira, P.; Dayyani, I. Mechanical characterization of a 3D large strain zero Poisson’s ratio helical metamaterial. Commun. Mater. 2025, 6, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Broccolo, S.; Laurenzi, S.; Scarpa, F. AUXHEX—A Kirigami inspired zero Poisson’s ratio cellular structure. Compos. Struct. 2017, 176, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, R. Strength of Materials, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ANSYS Material Designer User’s Guide. Available online: https://ansyshelp.ansys.com/public/Views/Secured/corp/v251/en/pdf/Material_Designer_Users_Guide.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

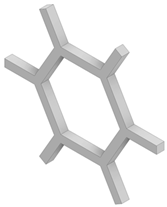

| Unit Cell | W [μm] | a [μm] | t [μm] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional honeycomb | 20 | 4.5 | 1 |

| Hex reentrant | 20 | 16 | 1 |

| Orthogonal grid | 20 | 6 | 4 |

| Rotating rectangles unit | 20 | 10 | 3 |

| Phase type Unit cell | Conventional Uniform honeycomb | Auxetic Hex reentrant |

| Geometry |  |  |

| Density ρ [kg/m3] | 165.890 | 195.820 |

| Young’s modulus Ex [MPa] | 10.566 | 2.192 |

| Young’s modulus Ey [MPa] | 20.980 | 17.135 |

| Poisson’s ratio ν | 0.650 | −0.329 |

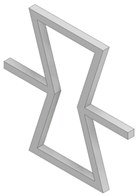

| Phase type Unit cell | Conventional Orthogonal grid | Auxetic Rotating rectangles unit |

| Geometry |  |  |

| Density ρ [kg/m3] | 659.200 | 929.400 |

| Young’s modulus Ex [MPa] | 732.060 | 740.260 |

| Young’s modulus Ey [MPa] | 732.060 | 740.260 |

| Poisson’s ratio ν | 0.164 | −0.046 |

| Case No. | Sample Inclusion Pattern | Inclusion Material | Matrix Material |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 vertical | Hex reentrant | Uniform honeycomb |

| 2 | 3 vertical | Uniform honeycomb | Hex reentrant |

| 3 | 3 vertical | Rotating rectangles unit | Orthogonal grid |

| 4 | 3 vertical | Orthogonal grid | Rotating rectangles unit |

| 5 | 3 horizontal | Hex reentrant | Uniform honeycomb |

| 6 | 3 horizontal | Uniform honeycomb | Hex reentrant |

| 7 | 3 horizontal | Rotating rectangles unit | Orthogonal grid |

| 8 | 3 horizontal | Orthogonal grid | Rotating rectangles unit |

| 9 | 9 | Hex reentrant | Uniform honeycomb |

| 10 | 9 | Uniform honeycomb | Hex reentrant |

| 11 | 9 | Rotating rectangles unit | Orthogonal grid |

| 12 | 9 | Orthogonal grid | Rotating rectangles unit |

| Sample Inclusion Pattern | Parameters Optimization Range [mm] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | C | d | e | f | |

| 3 vertical rectangles | 5–30 | 5–95 | 5–30 | 5–95 | - | - |

| 3 horizontal rectangles | 5–95 | 5–30 | 5–95 | 5–30 | - | - |

| 9 rectangles | 5–30 | 5–30 | 5–30 | 5–30 | 5–30 | 5–30 |

| Case No. | Inclusion Regions Dimensions [mm] | Effective Young’s Modulus [MPa] | Effective Poisson’s Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | |||

| 1 | 29.162 | 64.18 | 29.645 | 37.041 | 26.985 | 0.016 |

| 2 | 29.964 | 48.329 | 29.597 | 68.434 | 26.543 | −0.072 |

| 3 | 29.009 | 86.731 | 29.723 | 89.297 | 740.130 | −4.467 × 10−5 |

| 4 | 28.216 | 28.698 | 27.652 | 24.452 | 740.760 | −4.164 × 10−5 |

| Case No. | Inclusion Regions Dimensions [mm] | Effective Young’s Modulus [MPa] | Effective Poisson’s Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | |||

| 5 | 85.628 | 17.277 | 87.063 | 23.125 | 56.365 | 0.132 |

| 6 | 92.424 | 14.814 | 93.807 | 16.082 | 48.529 | 0.099 |

| 7 | 94.918 | 28.556 | 93.883 | 27.193 | 742.090 | 9.713 × 10−6 |

| 8 | 62.218 | 11.381 | 88.793 | 8.3644 | 742.960 | 1.928 × 10−4 |

| Case No. | Inclusion Regions Dimensions [mm] | Effective Young’s Modulus [MPa] | Effective Poisson’s Ratio | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | e | f | |||

| 9 | 22.402 | 26.615 | 28.944 | 20.317 | 29.019 | 17.655 | 45.820 | 0.055 |

| 10 | 27.573 | 12.933 | 28.541 | 18.167 | 28.999 | 19.296 | 37.200 | 0.092438 |

| 11 | 29.435 | 27.364 | 29.95 | 28.943 | 29.812 | 29.676 | 741.080 | –1.577 × 10−5 |

| 12 | 28.203 | 7.207 | 29.218 | 10.054 | 29.233 | 6.909 | 742.630 | 4.310 × 10−5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zawistowski, M.; Poteralski, A. Optimization of Mechanical Properties of Multiphase Materials with Auxetic Phase. Materials 2026, 19, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010103

Zawistowski M, Poteralski A. Optimization of Mechanical Properties of Multiphase Materials with Auxetic Phase. Materials. 2026; 19(1):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010103

Chicago/Turabian StyleZawistowski, Maciej, and Arkadiusz Poteralski. 2026. "Optimization of Mechanical Properties of Multiphase Materials with Auxetic Phase" Materials 19, no. 1: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010103

APA StyleZawistowski, M., & Poteralski, A. (2026). Optimization of Mechanical Properties of Multiphase Materials with Auxetic Phase. Materials, 19(1), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010103