Effect of Cryogenic Treatment on Low-Density Magnesium Multicomponent Alloys with Exceptional Ductility

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis

2.2. Physical Characterization

Density and Porosity

2.3. Microstructure

2.3.1. General Microstructure

2.3.2. Secondary Phase Analysis

2.3.3. X-Ray Diffraction

2.4. Thermal Characterization

2.5. Mechanical Characterization

2.5.1. Damping Response

2.5.2. Hardness

2.5.3. Compression

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Density and Porosity

3.2. Microstructure

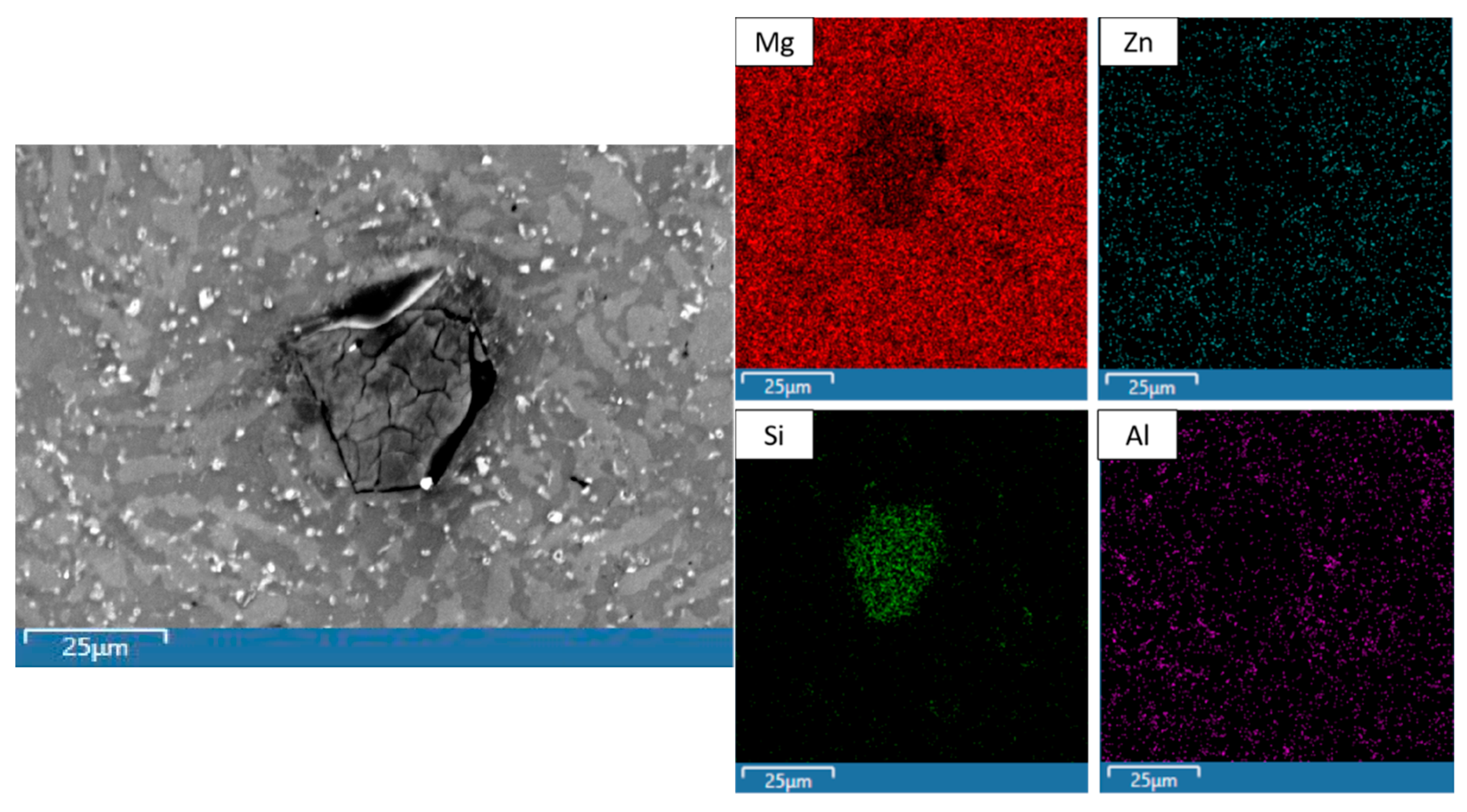

3.2.1. Secondary Phase Characterization

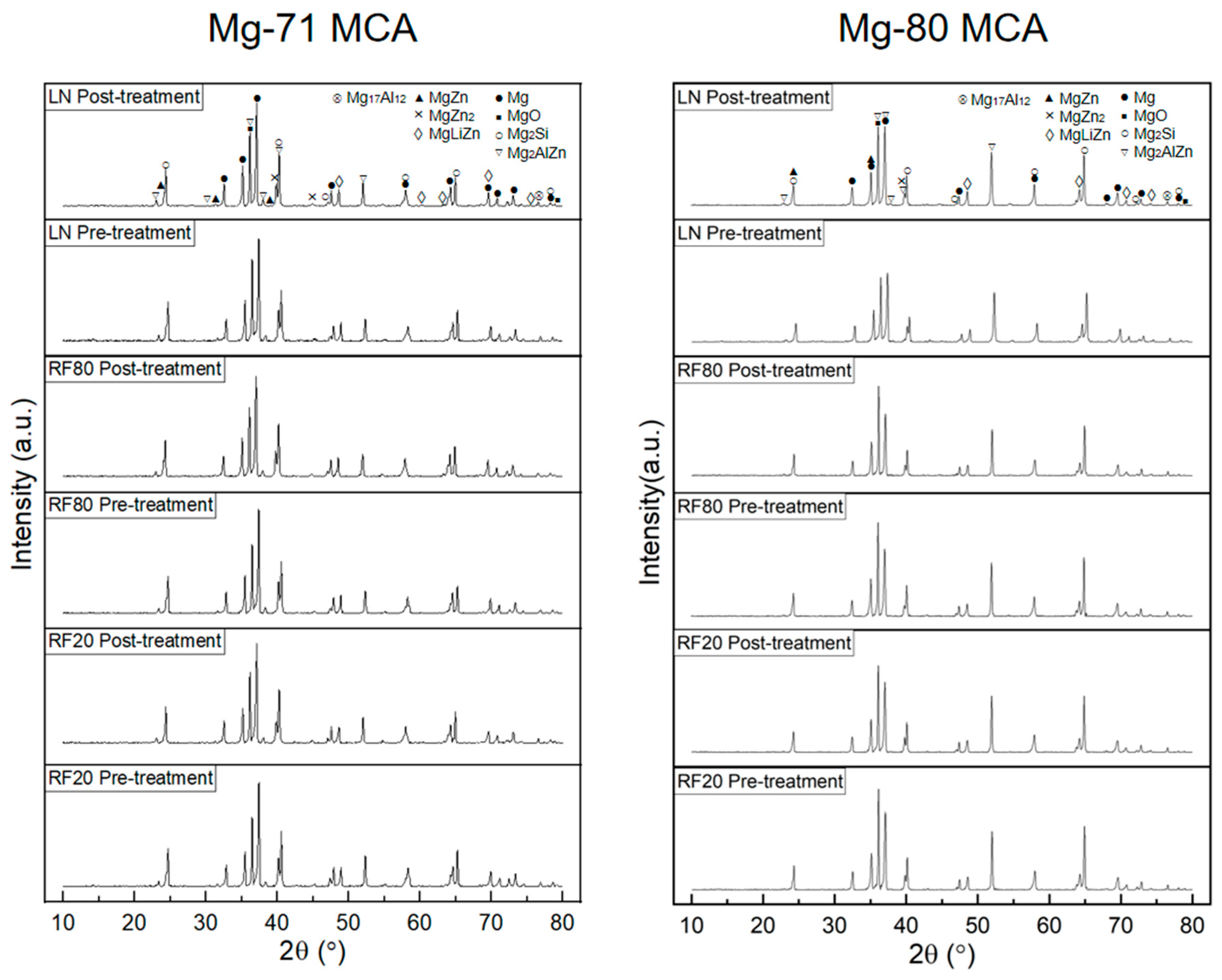

3.2.2. X-Ray Diffraction

3.2.3. Grain Characterization

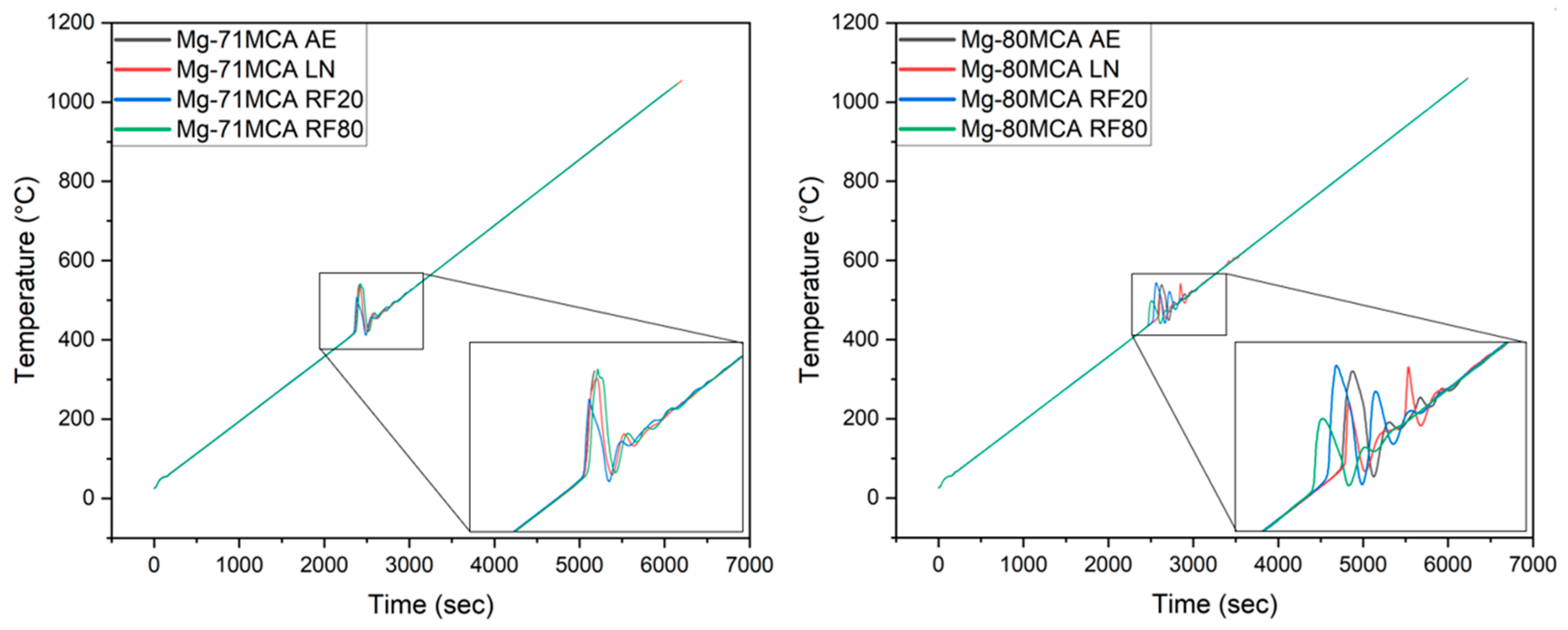

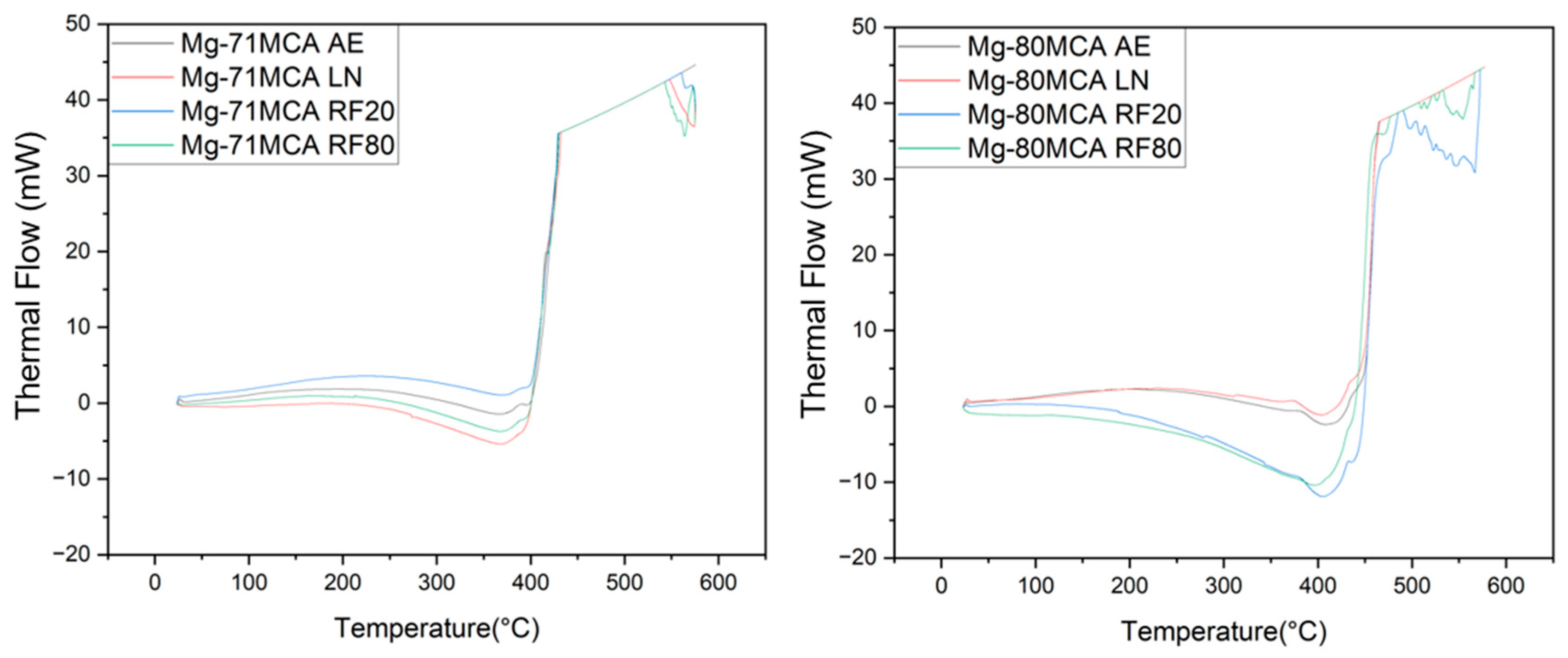

3.3. Thermal Response

3.4. Mechanical Characterization

3.4.1. Damping Response

3.4.2. Hardness

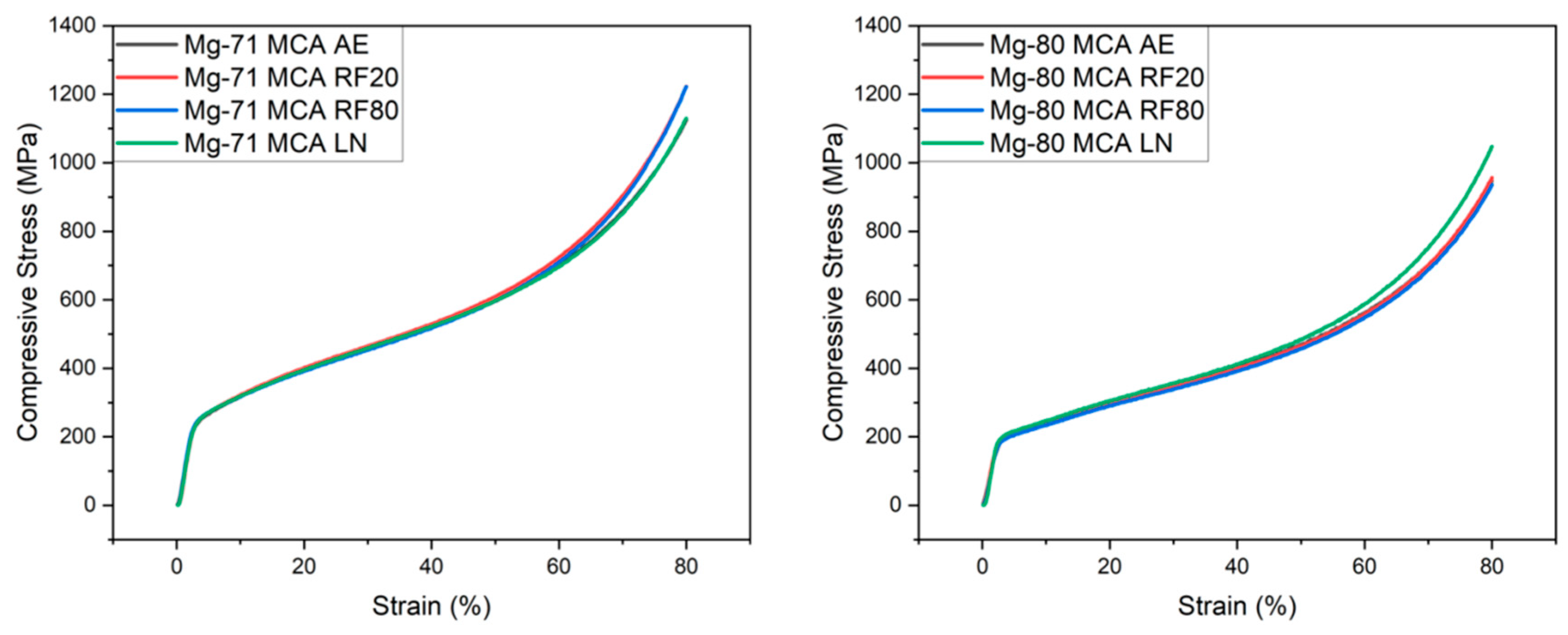

3.4.3. Compressive Response

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gupta, M.; Wong, W.L.E. Magnesium-based nanocomposites: Lightweight materials of the future. Mater. Charact. 2015, 105, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; She, J.; Chen, D.; Pan, F. Latest research advances on magnesium and magnesium alloys worldwide. J. Magnes. Alloys 2020, 8, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulekci, M.K. Magnesium and its alloys applications in automotive industry. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2008, 39, 851–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caceres, C.H. Economical and Environmental Factors in Light Alloys Automotive Applications. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2007, 38, 1649–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, L.; Yang, B.; Xu, B.; Liang, D.; Wang, F.; Tian, Y. Magnesium Alloy Scrap Vacuum Gasification—Directional Condensation to Purify Magnesium. Metals 2023, 13, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xiong, X.; Chen, J.; Peng, X.; Chen, D.; Pan, F. Research advances in magnesium and magnesium alloys worldwide in 2020. J. Magnes. Alloys 2021, 9, 705–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xiong, X.; Chen, J.; Peng, X.; Chen, D.; Pan, F. Research advances of magnesium and magnesium alloys worldwide in 2022. J. Magnes. Alloys 2023, 11, 2611–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.W.; Chen, S.K.; Lin, S.J.; Gan, J.Y.; Chin, T.S.; Shun, T.T.; Tsau, C.H.; Chang, S.Y. Nanostructured High-Entropy Alloys with Multiple Principal Elements: Novel Alloy Design Concepts and Outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.J.; Lin, J.P.; Chen, G.L.; Liaw, P.K. Solid-Solution Phase Formation Rules for Multi-component Alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2008, 10, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, E.J.; Jones, N.G. High-entropy alloys: A critical assessment of their founding principles and future prospects. Int. Mater. Rev. 2016, 61, 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.-W. Recent progress in high-entropy alloys. Eur. J. Control 2006, 31, 633–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Hou, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, T.; Zhou, N.; Zheng, K. Study on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg–Al–Li–Zn–Ti multi-component alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 4781–4795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanes, M.; Bin Gombari, A.A.; Gupta, M. Enhancing Multiple Properties of a Multicomponent Mg-Based Alloy Using a Sinterless Turning-Induced Deformation Technique. Technologies 2023, 11, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.-Z.; Zha, M.; Wang, S.-Q.; Wang, S.-C.; Wang, C.; Jia, H.-L.; Wang, H.-Y. Alloying design and microstructural control strategies towards developing Mg alloys with enhanced ductility. J. Magnes. Alloys 2022, 10, 1191–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; He, Y.; Huang, H. Effect of lithium content on the mechanical and corrosion behaviors of HCP binary Mg–Li alloys. J. Magnes. Alloys 2021, 9, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Chen, J.; Lin, Y.; Xue, Z.; Roven, H.J.; Skaret, P.C. Microstructure, mechanical properties and wear resistance of an Al–Mg–Si alloy produced by equal channel angular pressing. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2020, 30, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonar, T.; Lomte, S.; Gogte, C. Cryogenic Treatment of Metal—A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 25219–25228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Sidhu, H.; Singh, B.; Kumar, P. Effect of cryogenic treatment on corrosion behavior of friction stir processed magnesium alloy AZ91. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 10389–10395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieringa, H. Influence of Cryogenic Temperatures on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Magnesium Alloys: A Review. Metals 2017, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mónica, P.; Bravo, P.M.; Cárdenas, D. Deep cryogenic treatment of HPDC AZ91 magnesium alloys prior to aging and its influence on alloy microstructure and mechanical properties. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2017, 239, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- XingHe, T.; Chee Keat How, W.; Chan Kwok Weng, J.; Kwok Wai Onn, R.; Gupta, M. Development of high-performance quaternary LPSO Mg–Y–Zn–Al alloys by Disintegrated Melt Deposition technique. Mater. Des. 2015, 83, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E112-13; Standard Test Methods for Determining Average Grain Size. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM E384-16; Standard Test Method for Microindentation Hardness of Materials. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM E9-09; Standard Test Methods of Compression Testing of Metallic Materials at Room Temperature. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- Song, G.; Atrens, A. Understanding Magnesium Corrosion—A Framework for Improved Alloy Performance. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2003, 5, 837–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, R.M.; Grigore, M.E.; Iancu, L.; Ghioca, P.; Ion, R.-M. Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment: A Review on the Identification Methods for Polymeric Materials. Recycling 2019, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.-Y.; Chang, Y.A.; Zhang, F. A thermodynamic analysis of the Mg-Si system. J. Phase Equilibria 2000, 21, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barylski, A.; Aniołek, K.; Dercz, G.; Kupka, M.; Kaptacz, S. The effect of deep cryogenic treatment and precipitation hardening on the structure, micromechanical properties and wear of the Mg–Y-Nd-Zr alloy. Wear 2021, 468–469, 203587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates-Rector, S.; Blanton, T. The Powder Diffraction File: A quality materials characterization database. Powder Diffr. 2019, 34, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.; Tarfa, T.; Robinson, J.A.; Wagner, S.; Ochin, P.; Harmelin, M.G.; Seifert, H.J.; Lukas, H.L.; Aldinger, F. Experimental investigation and thermodynamic calculation of the Al–Mg–Zn system. Thermochim. Acta 1998, 314, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, D.; Chen, Z.; Liu, J. Effect of Cryogenic Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of AZ31 Magnesium Alloy. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2010, 25, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Sun, L.; Ma, H.; Jin, P. Effects of cryogenic treatment on microstructures and mechanical properties of Mg-2Nd-4Zn alloy. Mater. Lett. 2021, 305, 130699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.D.; Kumar, S.S. Effect of Heat Treatment Conditions and Cryogenic Treatment on Microhardness and Tensile Properties of AZ31B Alloy. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2023, 32, 8786–8794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.-r.; Wang, H.-m.; Cai, Y.; Zhao, Y.-t.; Wang, J.-j.; Gill, S.P.A. Microstructure and mechanical properties of AZ91 magnesium alloy subject to deep cryogenic treatments. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2013, 20, 896–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Parande, G.; Tun, K.S.; Gupta, M. Enhancing the Physical, Thermal, and Mechanical Responses of a Mg/2wt.%CeO2 Nanocomposite Using Deep Cryogenic Treatment. Metals 2023, 13, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassell, W.M.; Gulbransen, L.B.; Lewis, J.R.; Hamilton, J.H. Ignition Temperatures of Magnesium and Magnesium Alloys. JOM 1951, 3, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi Kumar, N.V.; Blandin, J.J.; Suéry, M.; Grosjean, E. Effect of alloying elements on the ignition resistance of magnesium alloys. Scr. Mater. 2003, 49, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Tang, X.; Li, J.; Le, W.; Jiao, Q.; Liu, D.; Jia, Y. Atomized Mg-Li spherical alloys: A new strategy for promoting reactivity of Mg. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 998, 174974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sole, K.; Johanes, M.; Gupta, M. Enhancing Microstructural, Thermal, Mechanical, and Corrosion Response of a Bio/Eco-Compatible Mg–2Zn–1Ca–0.3Mn Alloy Using Two Types of Cryogenic Treatments. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2024, 26, 2400738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanes, M.; Mehtabuddin, S.; Venkatarangan, V.; Gupta, M. An Insight into the Varying Effects of Different Cryogenic Temperatures on the Microstructure and the Thermal and Compressive Response of a Mg/SiO2 Nanocomposite. Metals 2024, 14, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asl, K.M.; Tari, A.; Khomamizadeh, F. Effect of deep cryogenic treatment on microstructure, creep and wear behaviors of AZ91 magnesium alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2009, 523, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekumalla, S.; Yang, C.; Seetharaman, S.; Wong, W.L.E.; Goh, C.S.; Shabadi, R.; Gupta, M. Enhancing overall static/dynamic/damping/ignition response of magnesium through the addition of lower amounts (<2%) of yttrium. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 689, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.-k.; Tane, M.; Hyun, S.-k.; Okuda, Y.; Nakajima, H. Vibration–damping capacity of lotus-type porous magnesium. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 417, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Jiang, G.; Dong, J.; Hou, J.; He, G. Damping behavior and energy absorption capability of porous magnesium. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 680, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovin, I.S.; Sinning, H.R. Internal friction in metallic foams and some related cellular structures. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 370, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovin, I.S.; Sinning, H.R.; Arhipov, I.K.; Golovin, S.A.; Bram, M. Damping in some cellular metalic materials due to microplasticity. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 370, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granato, A.; Lücke, K. Theory of Mechanical Damping Due to Dislocations. J. Appl. Phys. 1956, 27, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granato, A.; Lücke, K. Application of Dislocation Theory to Internal Friction Phenomena at High Frequencies. J. Appl. Phys. 1956, 27, 789–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zou, Y.; Dang, C.; Wan, Z.; Wang, J.; Pan, F. Research Progress and the Prospect of Damping Magnesium Alloys. Materials 2024, 17, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polmear, I.; StJohn, D.; Nie, J.-F.; Qian, M. 6—Magnesium Alloys. In Light Alloys, 5th ed.; Polmear, I., StJohn, D., Nie, J.-F., Qian, M., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 287–367. [Google Scholar]

- Che, B.; Lu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Ma, M.; Wang, L.; Qi, F. Effects of cryogenic treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of AZ31 magnesium alloy rolled at different paths. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 832, 142475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zhang, J. Microstructure and mechanical properties of AZ31 magnesium alloy processed by multi-directional forging at different temperatures. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 674, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.O. The Deformation and Ageing of Mild Steel: III Discussion of Results. Proc. Phys. Soc. Sect. B 1951, 64, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Yang, G.; Liu, Z.; Fu, S.; Gao, H. Effects of deep cryogenic treatment on microstructure, mechanical, and corrosion of ZK60 Mg alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 26, 3686–3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Guan, B.; Xin, Y.; Huang, G.; Wu, P.; Liu, Q. Revealing the role of pyramidal <c+a> slip in the high ductility of Mg-Li alloy. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 12, 1021–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, I.; Carter, E.A. First-principles simulations of plasticity in body-centered-cubic magnesium–lithium alloys. Acta Mater. 2014, 64, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, K. Highly-Ductile Magnesium Alloys: Atomistic-Flow Mechanisms and Alloy Designing. Materials 2019, 12, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, B.-C.; Shim, M.-S.; Shin, K.S.; Kim, N.J. Current issues in magnesium sheet alloys: Where do we go from here? Scr. Mater. 2014, 84–85, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material Designation | Composition (wt.%) | Elemental Composition (wt.%) | Total (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg | Li | Al | Zn | Si | |||

| Mg-71MCA | Mg-10Li-9Al-6Zn-4Si | 71 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 100 |

| Mg-80MCA | Mg-10Li-6Al-2Zn-2Si | 80 | 10 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| Condition | Material Designation Suffix |

|---|---|

| As-extruded, no further treatments | AE |

| Refrigerated at −20 °C for 24 h | RF20 |

| Refrigerated at −80 °C for 24 h | RF80 |

| Immersed in liquid nitrogen at −196 °C for 24 h | LN |

| Material | Measured Elemental Composition (wt.%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg | Li | Al | Zn | Si | |

| Mg-71MCA | 70.44 | 10.88 | 9.36 | 6.87 | 2.45 |

| Mg-80MCA | 80.29 | 10.18 | 6.36 | 1.85 | 1.32 |

| Material | Condition | Theoretical Density (g/cm3) | Experimental Density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mg-71MCA RF20 | Pre-treatment | 1.503 | 1.624 ± 0.001 |

| Post-treatment | 1.627 ± 0.003 (↑ 0.18%) | ||

| Mg-71MCA RF80 | Pre-treatment | 1.627 ± 0.001 | |

| Post-treatment | 1.632 ± 0.004 (↑ 0.31%) | ||

| Mg-71MCA LN | Pre-treatment | 1.626 ± 0.002 | |

| Post-treatment | 1.629 ± 0.010 (↑ 0.18%) | ||

| Mg-80MCA RF20 | Pre-treatment | 1.458 | 1.552 ± 0.004 |

| Post-treatment | 1.555 ± 0.005 (↑ 0.19%) | ||

| Mg-80MCA RF80 | Pre-treatment | 1.551 ± 0.004 | |

| Post-treatment | 1.552 ± 0.003 (↑ 0.06%) | ||

| Mg-80MCA LN | Pre-treatment | 1.554 ± 0.003 | |

| Post-treatment | 1.550 ± 0.003 (↓ 0.26%) |

| Material | Spectrum | Detected Element (wt.%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg | Al | Zn | Si | ||

| Mg-71MCA AE | 1 | 48.59 | 1.49 | 1.38 | 48.54 |

| 2 | 78.83 | 3.92 | 17.04 | 0.21 | |

| 3 | 77.67 | 8.16 | 13.85 | 0.32 | |

| 4 | 73.78 | 7.68 | 18.11 | 0.43 | |

| Mg-71MCA RF20 | 1 | 50.89 | 2.65 | 4.55 | 41.92 |

| 2 | 80.03 | 5.15 | 13.97 | 0.86 | |

| 3 | 75.75 | 7.52 | 15.77 | 0.95 | |

| 4 | 45.30 | 21.77 | 32.27 | 0.66 | |

| Mg-71MCA RF80 | 1 | 51.91 | 1.93 | 2.47 | 43.69 |

| 2 | 83.39 | 4.19 | 11.43 | 0.98 | |

| 3 | 64.02 | 12.02 | 23.45 | 0.51 | |

| 4 | 53.41 | 18.77 | 26.12 | 1.70 | |

| Mg-71MCA LN | 1 | 53.06 | 0.52 | 1.25 | 45.18 |

| 2 | 83.26 | 1.81 | 14.83 | 0.10 | |

| 3 | 85.71 | 4.60 | 8.61 | 1.09 | |

| 4 | 30.29 | 27.71 | 41.51 | 0.49 | |

| Material | Spectrum | Detected Element (wt.%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg | Al | Zn | Si | ||

| Mg-80MCA AE | 1 | 53.09 | 0.83 | 0.50 | 45.58 |

| 2 | 90.17 | 3.29 | 6.43 | 0.11 | |

| 3 | 86.88 | 7.10 | 5.91 | 0.11 | |

| 4 | 35.49 | 27.92 | 30.71 | 5.88 | |

| Mg-80MCA RF20 | 1 | 51.67 | 1.41 | 0.79 | 46.13 |

| 2 | 76.57 | 9.28 | 7.49 | 6.66 | |

| 3 | 75.79 | 5.44 | 4.74 | 14.03 | |

| 4 | 89.48 | 4.69 | 5.03 | 0.80 | |

| Mg-80MCA RF80 | 1 | 52.79 | 1.63 | 0.79 | 44.79 |

| 2 | 87.31 | 6.19 | 6.05 | 0.45 | |

| 3 | 89.04 | 4.52 | 5.99 | 0.45 | |

| 4 | 89.28 | 4.78 | 5.26 | 0.68 | |

| Mg-80MCA LN | 1 | 46.83 | 0.87 | 0.00 | 52.30 |

| 2 | 92.89 | 3.28 | 3.71 | 0.11 | |

| 3 | 85.43 | 8.54 | 5.69 | 0.33 | |

| 4 | 87.85 | 5.03 | 7.00 | 0.11 | |

| Material | Condition | Secondary Phase Area Fraction (%) | Average Secondary Phase Diameter (µm) | Aspect Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg-71MCA | AE | 15.3 | 2.64 ± 0.87 | 2.02 ± 0.83 |

| RF20 | 22.6 (↑ 47.2%) | 2.86 ± 1.08 (↑ 8.3%) | 2.01 ± 0.84 | |

| RF80 | 16.4 (↑ 7.0%) | 3.35 ± 1.11 (↑ 26.8%) | 2.06 ± 0.85 | |

| LN | 25.2 (↑ 64.6%) | 3.04 ± 1.14 (↑ 15.2%) | 1.98 ± 0.75 | |

| Mg-80MCA | AE | 12.3 | 1.67 ± 0.81 | 1.99 ± 0.88 |

| RF20 | 11.0 (↓ 10.5%) | 1.82 ± 0.81 (↑ 8.6%) | 1.75 ± 0.64 | |

| RF80 | 10.5 (↓ 14.4%) | 1.75 ± 0.72 (↑ 4.5%) | 1.90 ± 0.77 | |

| LN | 14.0 (↑ 13.8%) | 1.71 ± 0.78 (↑ 2.5%) | 2.07 ± 1.07 |

| Material | Crystal Plane | Relative Intensity (I/Imax) | Absolute Intensity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Treatment | Post Treatment | Pre-Treatment | Post Treatment | ||

| Mg-71MCA RF20 | 10-10 Prismatic | 0.2075 | 0.2233 | 249 | 203 |

| 0002 Basal | 0.3358 | 0.3454 | 403 | 314 | |

| 10-11 Pyramidal | 1 | 1 | 1200 | 909 | |

| Mg-71MCA RF80 | 10-10 Prismatic | 0.2045 | 0.2029 | 247 | 255 |

| 0002 Basal | 0.3667 | 0.3811 | 443 | 479 | |

| 10-11 Pyramidal | 1 | 1 | 1208 | 1257 | |

| Mg-71MCA LN | 10-10 Prismatic | 0.2147 | 0.2199 | 146 | 316 |

| 0002 Basal | 0.3971 | 0.389 | 270 | 559 | |

| 10-11 Pyramidal | 1 | 1 | 680 | 1437 | |

| Mg-80MCA RF20 | 10-10 Prismatic | 0.2382 | 0.2251 | 257 | 219 |

| 0002 Basal | 0.4717 | 0.4728 | 509 | 460 | |

| 10-11 Pyramidal | 1 | 1 | 1079 | 973 | |

| Mg-80MCA RF80 | 10-10 Prismatic | 0.2341 | 0.2378 | 257 | 210 |

| 0002 Basal | 0.5537 | 0.5436 | 608 | 480 | |

| 10-11 Pyramidal | 1 | 1 | 1098 | 883 | |

| Mg-80MCA LN | 10-10 Prismatic | 0.2334 | 0.228 | 225 | 251 |

| 0002 Basal | 0.4616 | 0.4269 | 445 | 470 | |

| 10-11 Pyramidal | 1 | 1 | 964 | 1101 | |

| Material | Condition | Average Grain Diameter (µm) | Aspect Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mg-71MCA | AE | 4.03 ± 1.17 | 1.52 ± 0.36 |

| RF20 | 3.46 ± 1.05 (↓ 14.1%) | 1.50 ± 0.33 | |

| RF80 | 3.64 ± 1.23 (↓ 9.7%) | 1.46 ± 0.43 | |

| LN | 2.96 ± 0.89 (↓ 26.6%) | 1.45 ± 0.33 | |

| Mg-80MCA | AE | 3.91 ± 1.11 | 1.40 ± 0.25 |

| RF20 | 3.54 ± 1.13 (↓ 9.5%) | 1.36 ± 0.19 | |

| RF80 | 3.65 ± 1.07 (↓ 6.7%) | 1.50 ± 0.38 | |

| LN | 2.82 ± 1.03 (↓ 27.9%) | 1.44 ± 0.25 |

| Material | Condition | Ignition Temperature (°C) | Average CTE (10−6/K) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mg-71MCA | AE | 417 | 28.9 ± 3.2 |

| RF20 | 417 | 28.8 ± 3.1 (↓ 0.3%) | |

| RF80 | 416 | 26.4 ± 4.9 (↓ 8.7%) | |

| LN | 420 | 28.9 ± 2.5 (↑ 0%) | |

| Mg-80MCA | AE | 456 | 26.6 ± 4.3 |

| RF20 | 459 | 28.4 ± 3.4 (↑ 6.6%) | |

| RF80 | 448 | 30.9 ± 2.4 (↑ 16.1%) | |

| LN | 436 | 25.7 ± 5.6 (↓ 3.6%) |

| Material | Condition | Attenuation Coefficient | Damping Capacity (×10−4) | E-Modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg-71MCA RF20 | Pre-treatment | 27.50 | 4.84 | 53.09 |

| Post-treatment | 32.08 (↑ 16.6%) | 5.21 (↑ 7.6%) | 54.97 (↑ 3.5%) | |

| Mg-71MCA RF80 | Pre-treatment | 37.88 | 6.08 | 53.98 |

| Post-treatment | 30.77 (↓ 18.8%) | 4.86 (↓ 20.1%) | 55.00 (↑ 1.9%) | |

| Mg-71MCA LN | Pre-treatment | 37.96 | 7.38 | 53.13 |

| Post-treatment | 37.82 (↓ 0.4%) | 6.90 (↓ 6.5%) | 53.82 (↑ 1.3%) | |

| Mg-80MCA RF20 | Pre-treatment | 26.58 | 4.92 | 52.08 |

| Post-treatment | 33.93 (↑ 27.7%) | 5.92 (↑ 20.3%) | 51.85 (↓ 0.4%) | |

| Mg-80MCA RF80 | Pre-treatment | 32.53 | 5.00 | 52.59 |

| Post-treatment | 35.73 (↑ 9.8%) | 5.87 (↑ 17.4%) | 51.46 (↓ 2.1%) | |

| Mg-80MCA LN | Pre-treatment | 30.48 | 6.00 | 51.07 |

| Post-treatment | 27.60 (↓ 9.4%) | 5.18 (↓ 13.7%) | 51.97 (↑ 1.8%) |

| Material | Condition | Average Microhardness (HV) |

|---|---|---|

| Mg-71MCA | AE | 104 ± 4 |

| RF20 | 108 ± 5 (↑ 3.9%) | |

| RF80 | 112 ± 4 (↑ 7.7%) | |

| LN | 113 ± 5 (↑ 8.7%) | |

| Mg-80MCA | AE | 85 ± 3 |

| RF20 | 90 ± 1 (↑ 5.9%) | |

| RF80 | 91 ± 3 (↑ 7.1%) | |

| LN | 93 ± 2 (↑ 9.4%) |

| Material | Condition | Mean 0.2% Yield Strength (MPa) | Mean Ultimate Compressive Strength (MPa) | Mean Fracture Strain (%) | Mean Energy Absorbed (MJ/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg-71MCA | AE | 202 ± 6 | 1132 ± 30 | >80 | 447 ± 4 |

| RF20 | 226 ± 13 (↑ 12.1%) | 1208 ± 62 (↑ 6.7%) | >80 | 454 ± 7 (↑ 1.6%) | |

| RF80 | 226 ± 10 (↑ 11.9%) | 1194 ± 66 (↑ 5.5%) | >80 | 455 ± 7 (↑ 1.9%) | |

| LN | 227 ± 9 (↑ 12.7%) | 1142 ± 20 (↑ 0.9%) | >80 | 445 ± 1 (↓ 0.4%) | |

| Mg-80MCA | AE | 176 ± 8 | 986 ±41 | >80 | 354 ± 6 |

| RF20 | 165 ± 1 (↓ 6.5%) | 967 ± 23 (↓ 2.0%) | >80 | 351 ± 2 (↓ 0.9%) | |

| RF80 | 164 ± 7 (↓ 7.0%) | 944 ± 45 (↓ 4.3%) | >80 | 344 ± 6 (↓ 2.7%) | |

| LN | 183 ± 2 (↑ 3.6%) | 1044 ± 38 (↑ 5.9%) | >80 | 372 ± 5 (↑ 5.1%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fang, Y.; Johanes, M.; Gupta, M. Effect of Cryogenic Treatment on Low-Density Magnesium Multicomponent Alloys with Exceptional Ductility. Materials 2026, 19, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010100

Fang Y, Johanes M, Gupta M. Effect of Cryogenic Treatment on Low-Density Magnesium Multicomponent Alloys with Exceptional Ductility. Materials. 2026; 19(1):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010100

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Yu, Michael Johanes, and Manoj Gupta. 2026. "Effect of Cryogenic Treatment on Low-Density Magnesium Multicomponent Alloys with Exceptional Ductility" Materials 19, no. 1: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010100

APA StyleFang, Y., Johanes, M., & Gupta, M. (2026). Effect of Cryogenic Treatment on Low-Density Magnesium Multicomponent Alloys with Exceptional Ductility. Materials, 19(1), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010100