Study on the Complex Band Structure and Auxetic Behavior of Fractal Re-Entrant Honeycomb Metamaterials

Highlights

- Higher-order re-entrant honeycomb MM is proposed using multi-level features.

- The complex band structure was systematically investigated.

- The auxetic behavior is demonstrated and correlated with structural hierarchy.

- The results provide insights into coupling band structures with auxetic mechanisms.

- The design strategy supports the development of multifunctional metamaterials.

- The study offers guidance for acoustic and mechanical metamaterial design.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model and Methods

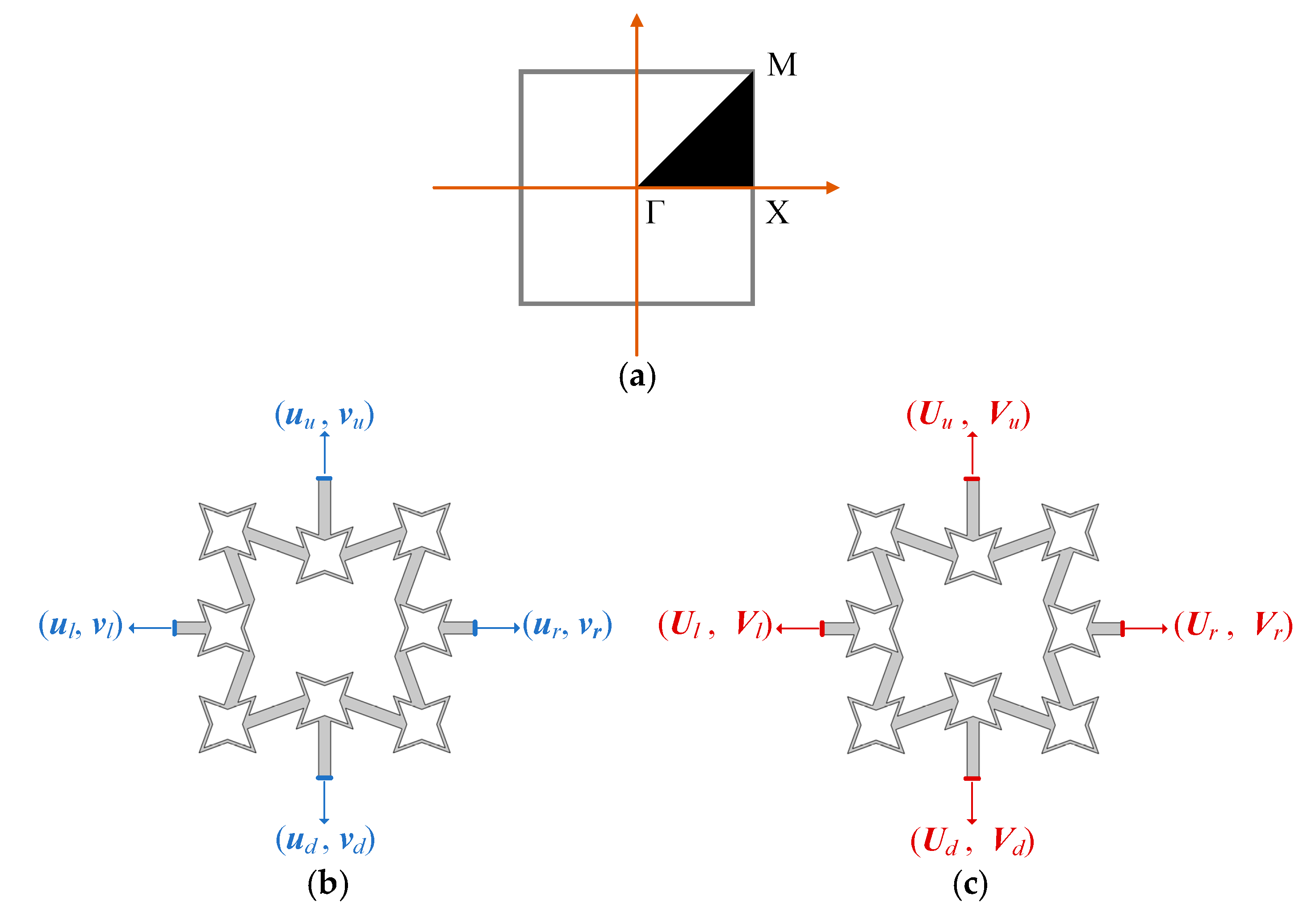

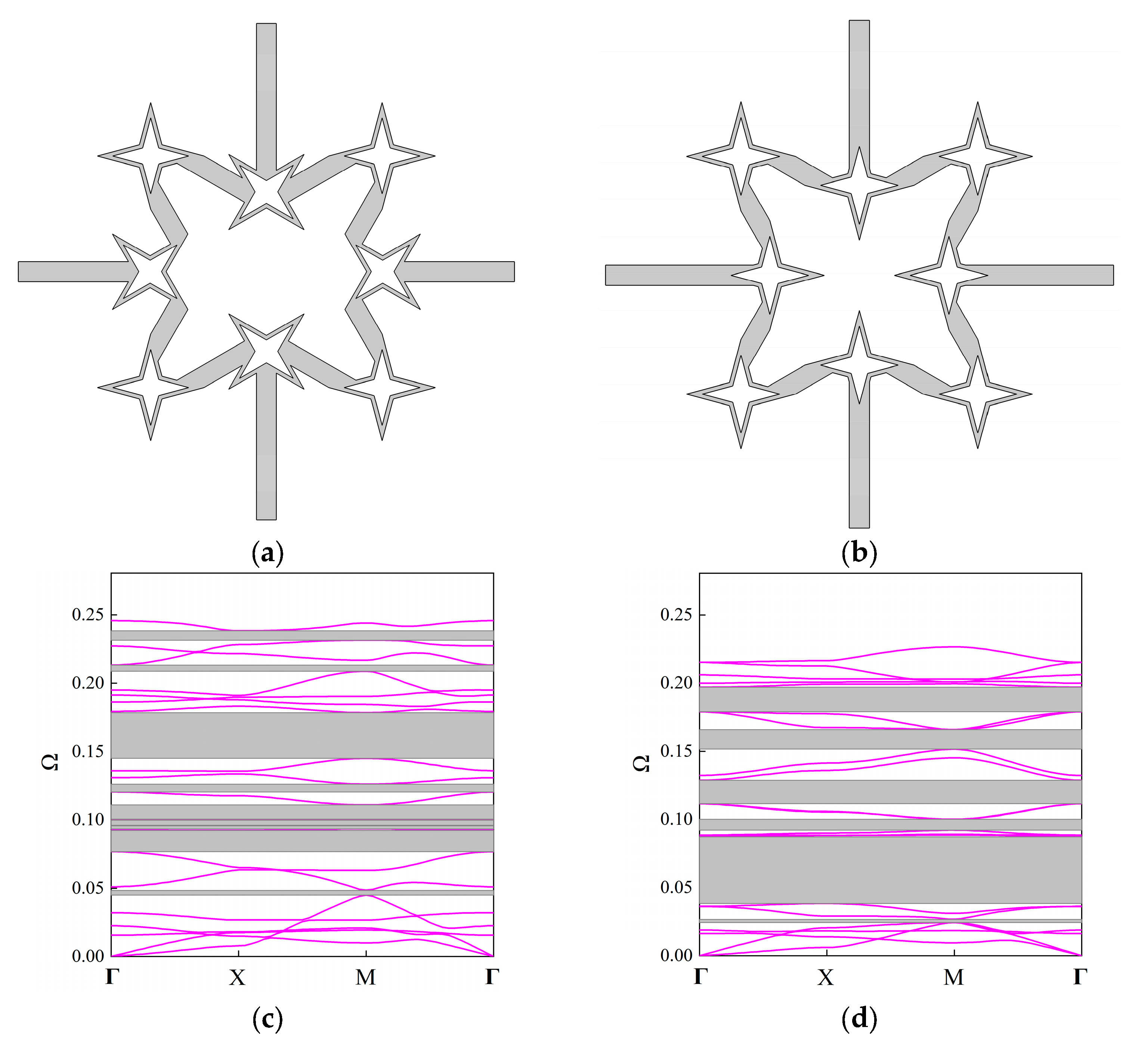

2.1. Fractal Re-Entrant Honeycomb Metamaterial Design

2.2. Complex Wave Dispersion Relation

2.3. The Auxetic Properties Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

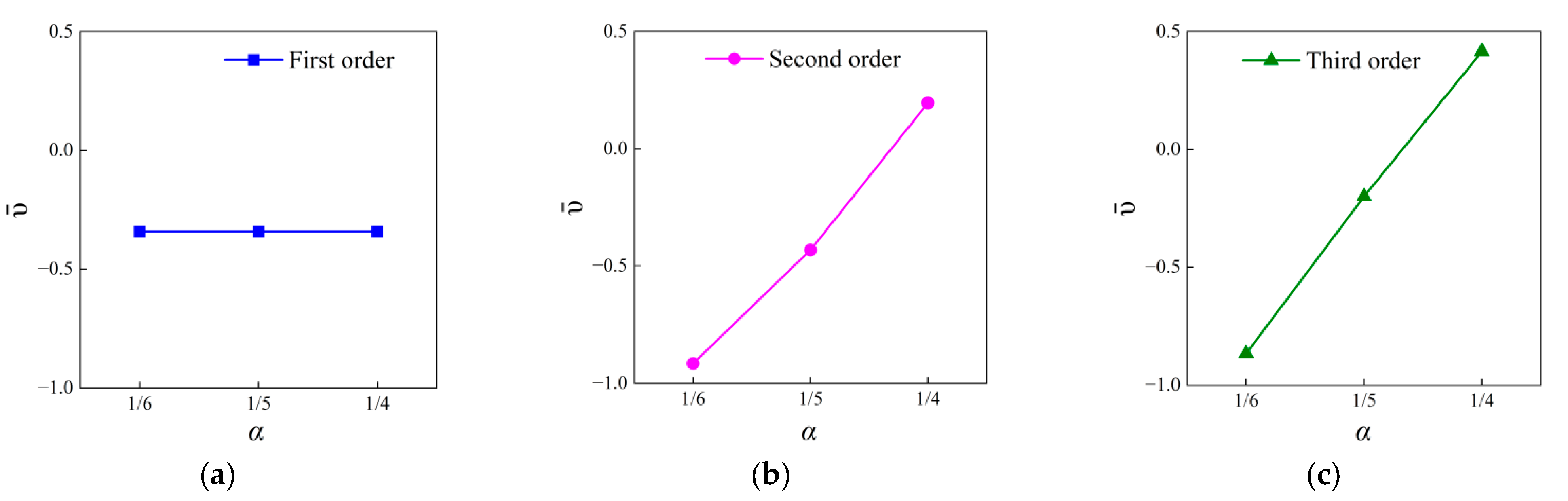

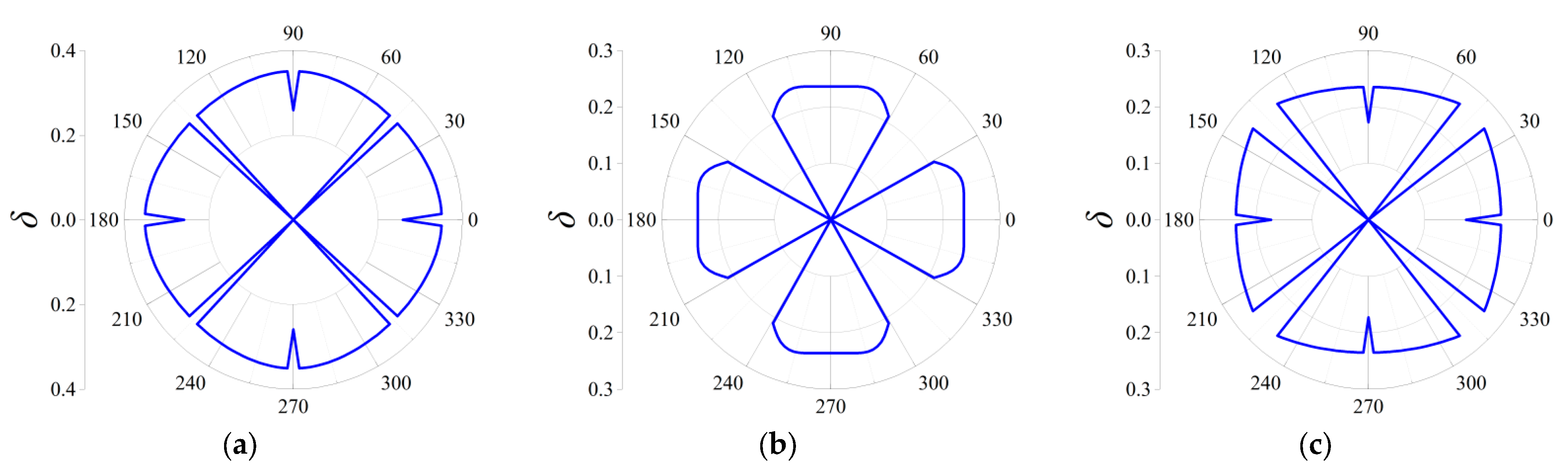

3.1. The Auxetic Behavior Analysis with Fractal Technique

3.2. Complex Band Structure of FRHM

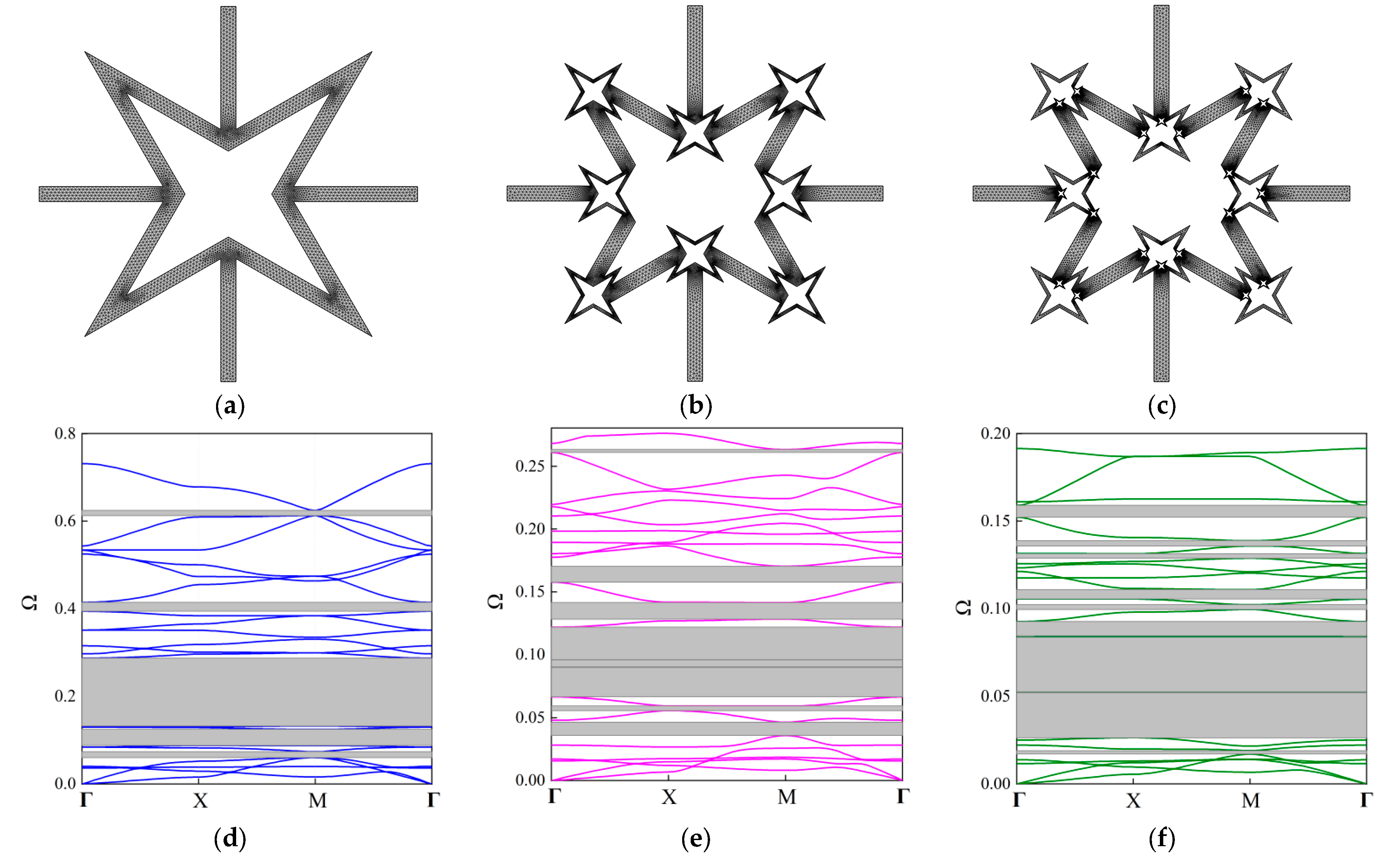

3.2.1. Real Band Diagram

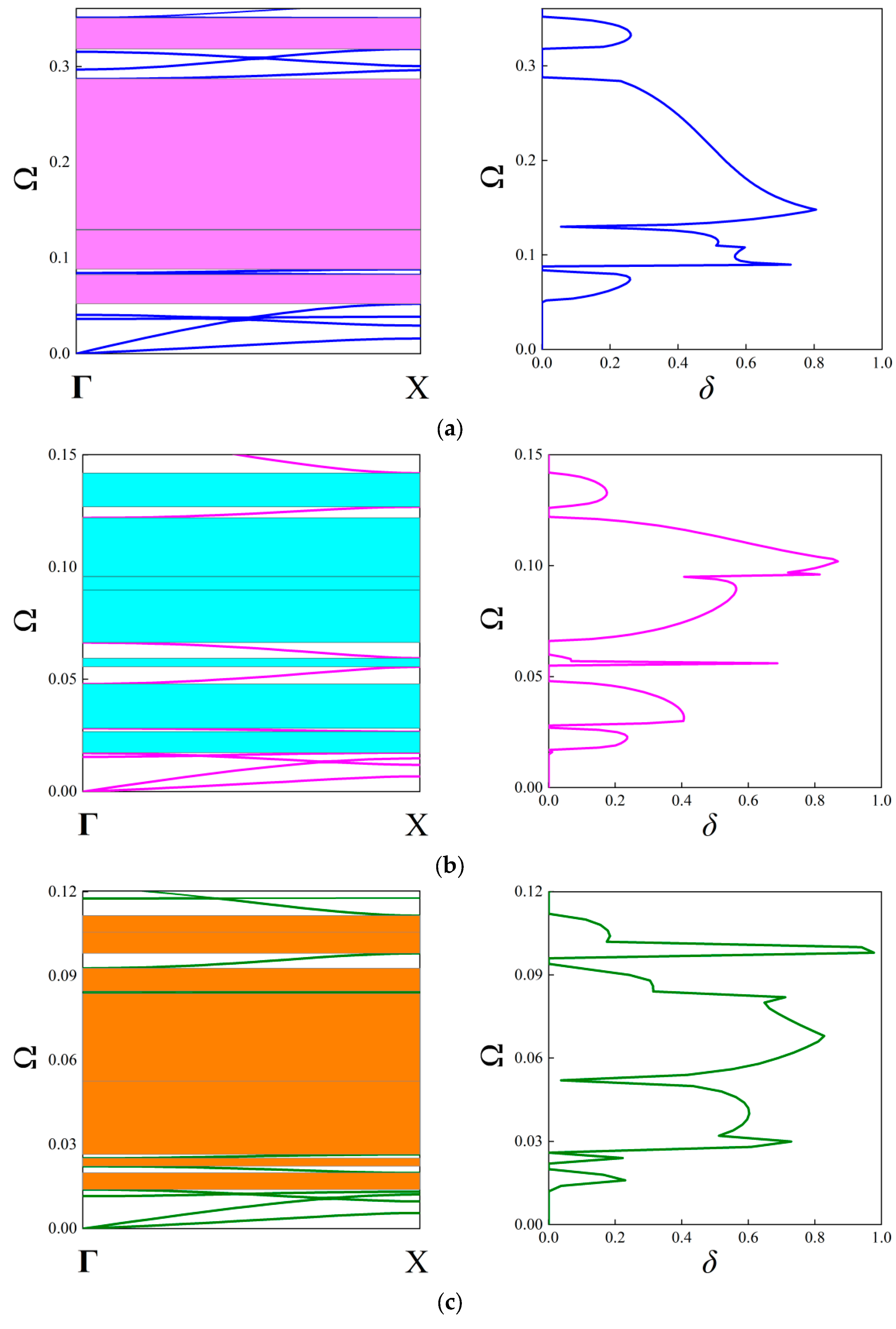

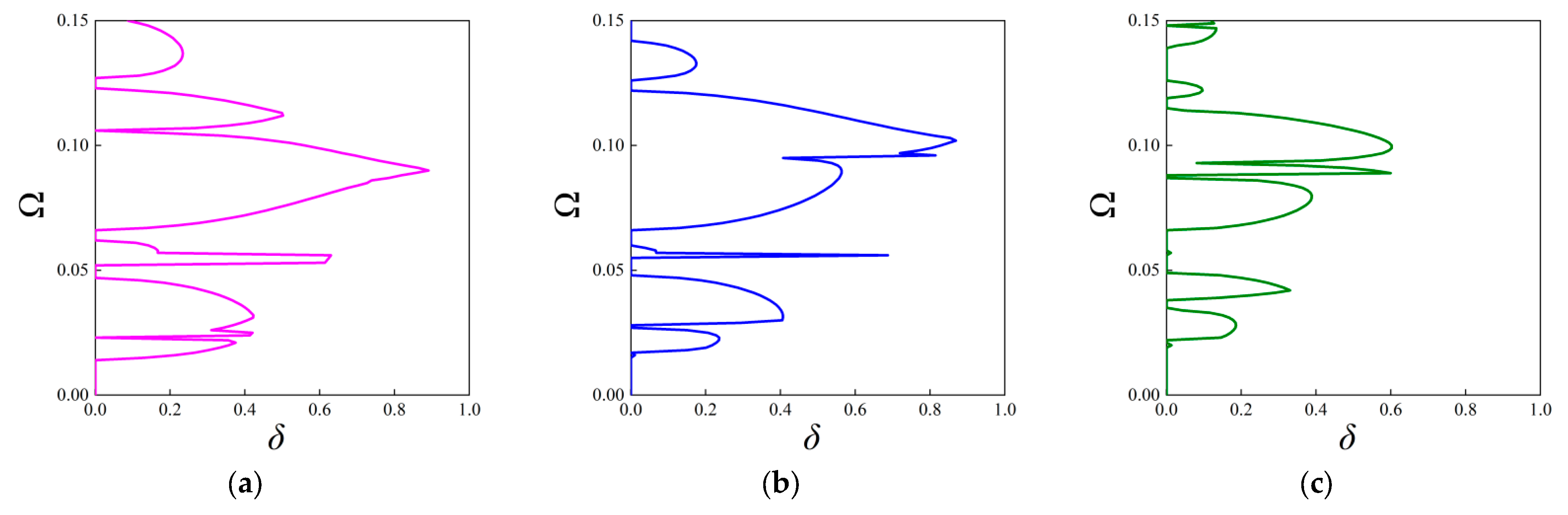

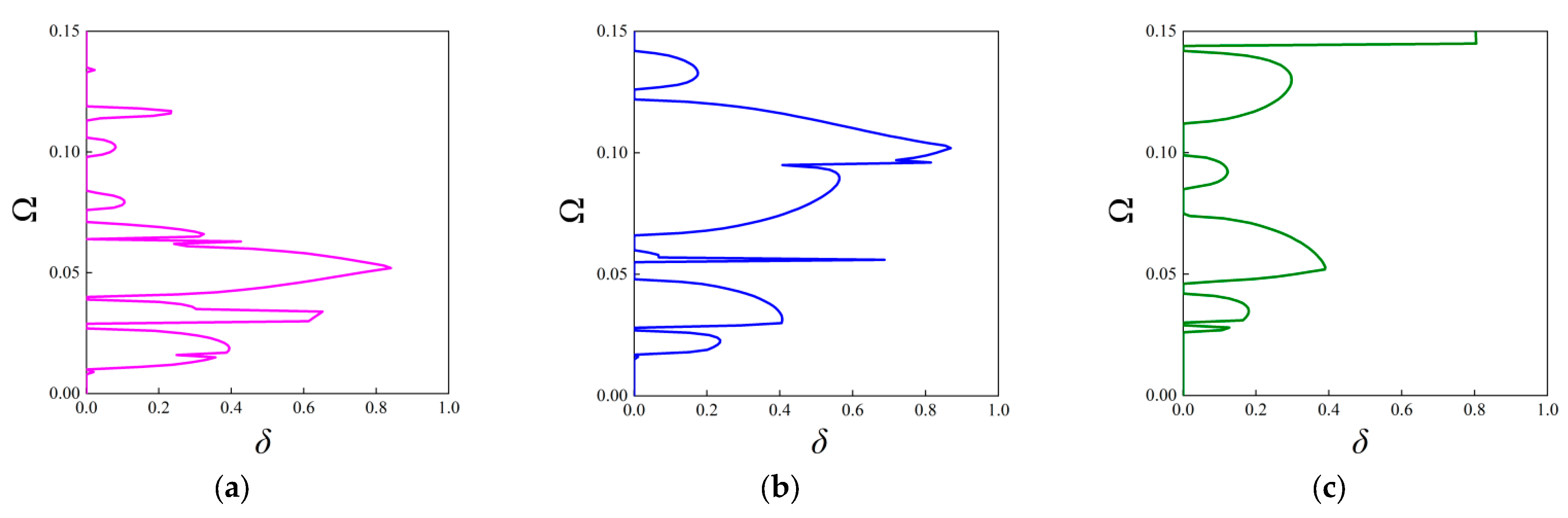

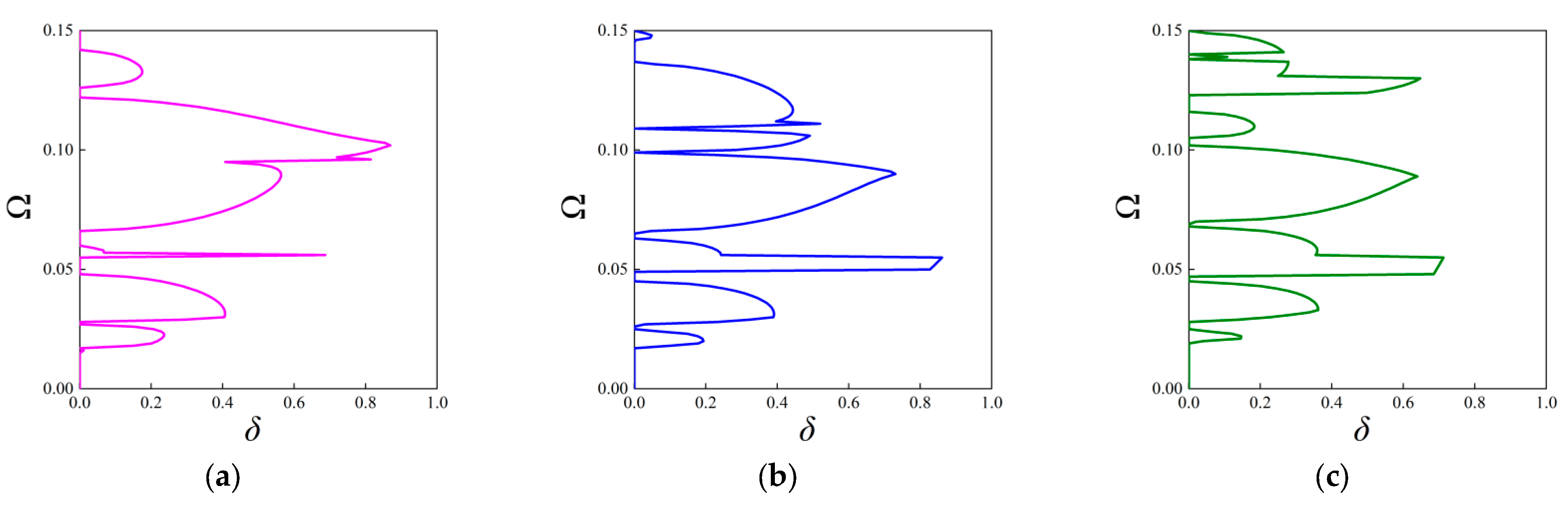

3.2.2. The Attenuation Diagrams

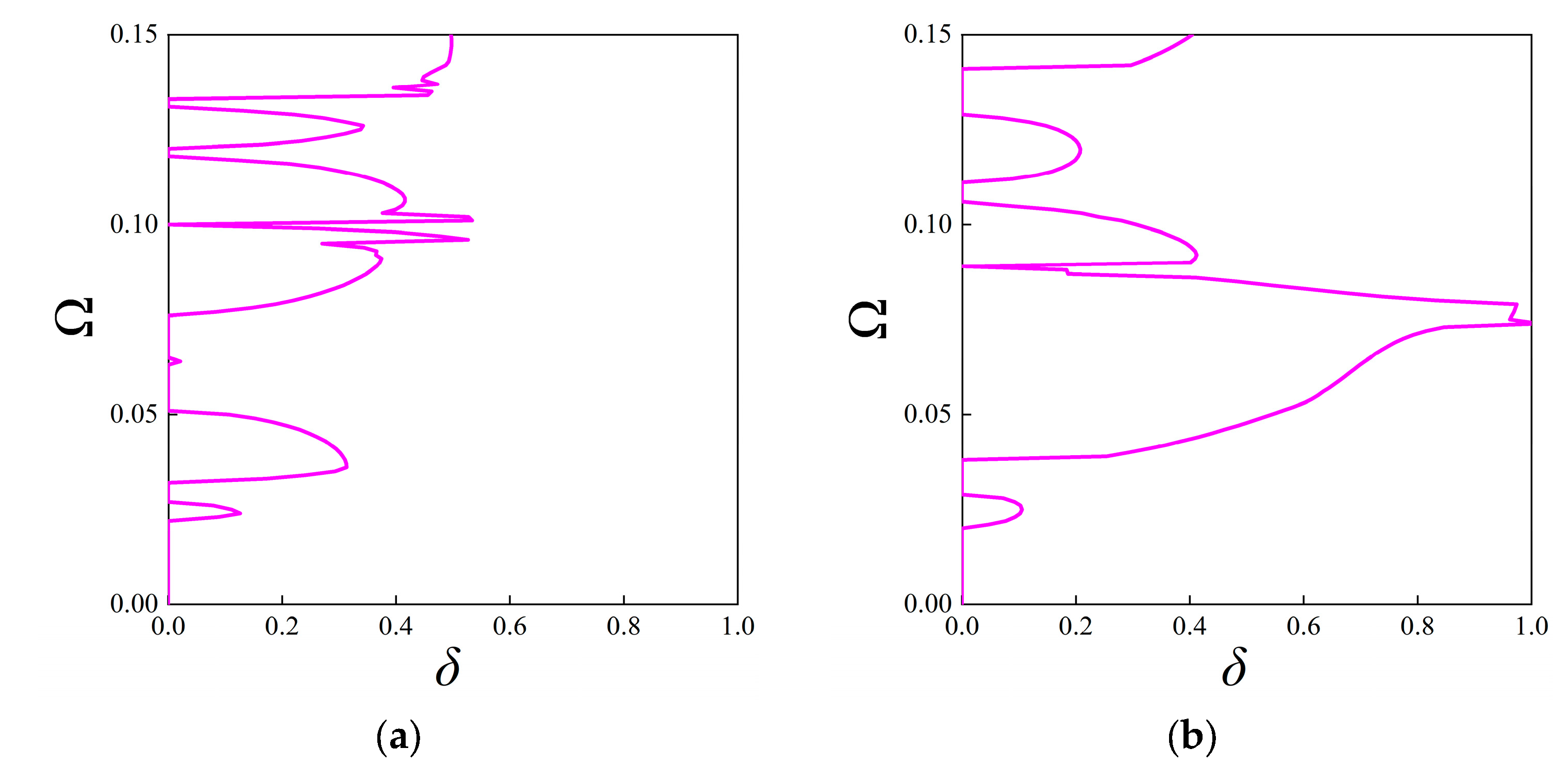

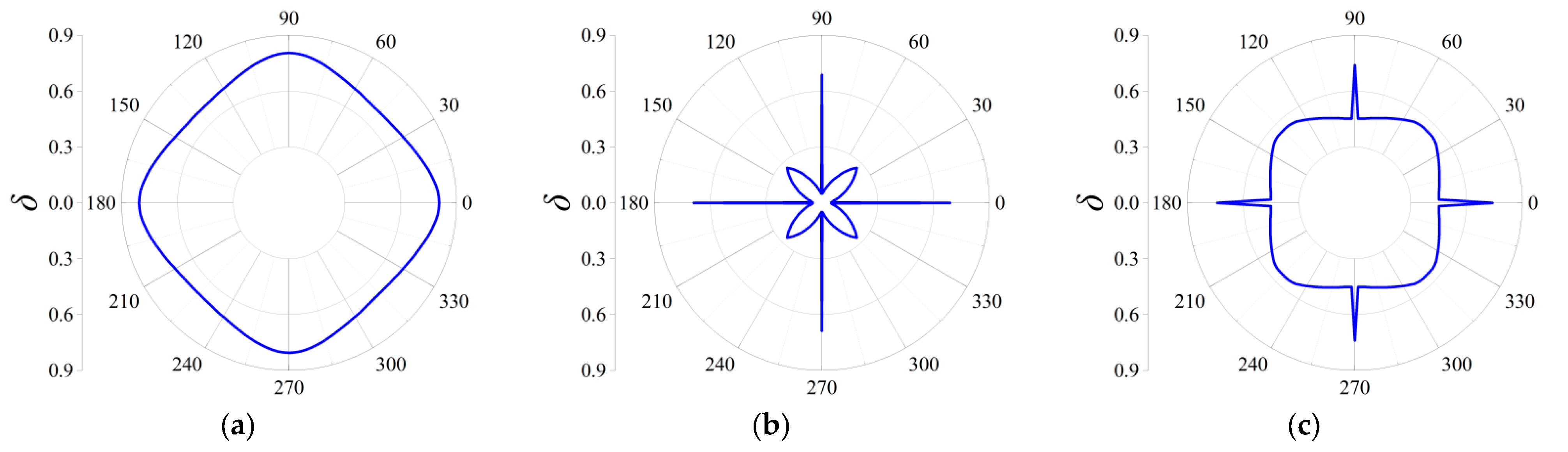

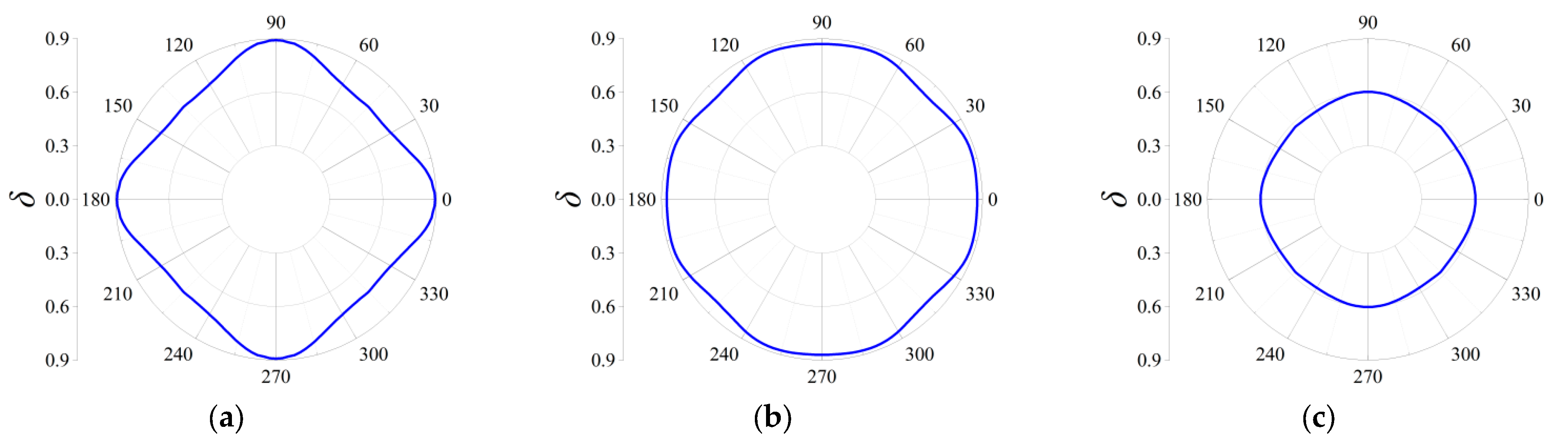

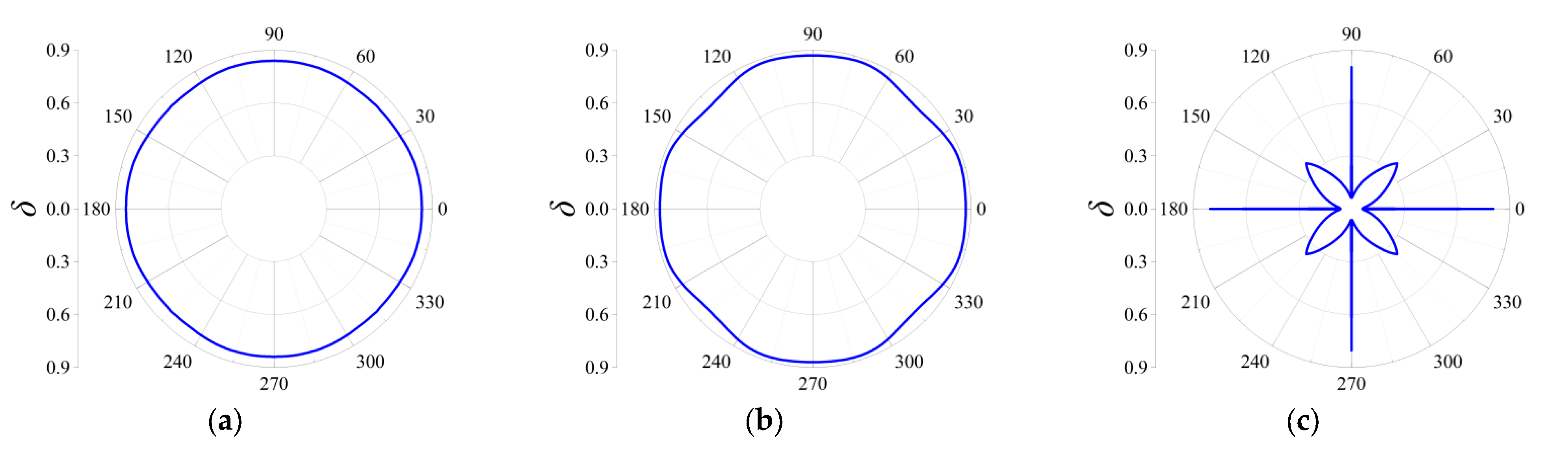

3.2.3. Directionality of Elastic Wave Decaying

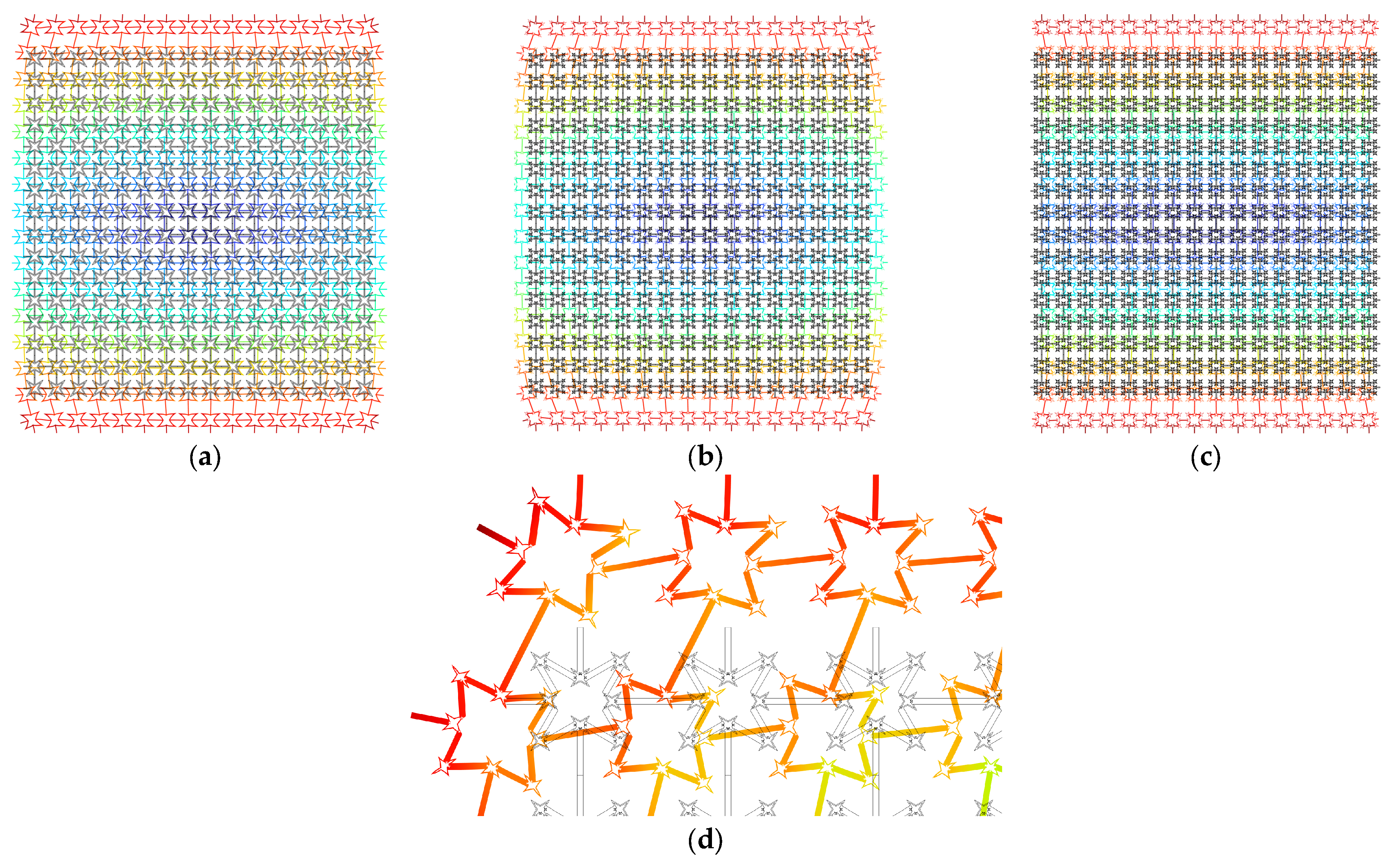

3.2.4. The Parametric Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fernandez-Corbaton, I.; Rockstuhl, C.; Ziemke, P.; Gumbsch, P.; Albiez, A.; Schwaiger, R.; Frenzel, T.; Kadic, M.; Wegener, M. New Twists of 3D Chiral Metamaterials. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1807742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, K.T.; Huang, H.H.; Sun, C.T. Optimizing the band gap of effective mass negativity in acoustic metamaterials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 241902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, P.; Liu, J.; Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Ouyang, X.; Jiang, J.H.; Huang, J. Tunable liquid–solid hybrid thermal metamaterials with a topology transition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2217068120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, T.; Hu, R. Inverse design of thermal metamaterials with holey engineering strategy. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 132, 145102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, S.; Masutani, T.; Sato, H. Locally resonant metamaterials damped by particles embedded through additive manufacturing. J. Sound. Vib. 2025, 596, 118715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wan, W.; Bao, J.; Gao, Y. Design optimization of elastic metamaterials with multilayered honeycomb structure by Kriging surrogate model and genetic algorithm. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2024, 67, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, W.M.; Shang, N.; Ma, L. Experimental study on the impact resistance of fill-enhanced mechanical metamaterials. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 285, 109799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dou, S.; Du, Y.; Liang, R.; Yue, S.; Zhao, L.; Liu, F.; Sun, Z.; Yang, J. Enhanced broadband low-frequency performance of negative Poisson’s ratio metamaterials with added mass. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Y.B.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Lim, K.M.; Lee, H.P. Acoustic metamaterial using hollowed star-shaped structure with slits. Appl. Acoust. 2025, 240, 110893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xiao, X.; Han, J.; He, Y. Honeycomb-cored hierarchical acoustic metamaterials: A synergistically coupled architecture for enhanced broadband sound absorption. Compos. Struct. 2025, 370, 119409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, L.; Ardito, R.; Braghin, F.; Corigliano, A. Low frequency 3D ultra-wide vibration attenuation via elastic metamaterial. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Sun, S.; Deng, L.; Yang, J.; Zhang, S.; Du, H.; Li, W. Investigation of a new metamaterial magnetorheological elastomer isolator with tunable vibration bandgaps. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 2022, 170, 108806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Yang, J.; Jiao, S.; Long, X. Band-stop characteristics of a nonlinear anti-resonant vibration isolator for low-frequency applications. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 240, 107914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, L.; Belloni, E.; Ardito, R.; Braghin, F.; Corigliano, A. Mechanical low-frequency filter via modes separation in 3D periodic structures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 111, 231902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Jeon, W. Ultra-wide low-frequency band gap in a tapered phononic beam. J. Sound. Vib. 2021, 499, 115977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Ma, L.; Ou, Z.; Lei, F. Propagation characteristics of lamb waves in a functionally graded material plate with periodic gratings. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2024, 31, 1645–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, X.f.; Xia, B.z.; Luo, Z.; Liu, J. 3D Hilbert fractal acoustic metamaterials: Low-frequency and multi-band sound insulation. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2019, 52, 195302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chong, Y.B.; Lim, K.M.; Lee, H.P. Reconfigurable 3D printed acoustic metamaterial chamber for sound insulation. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 266, 108978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, G.; Lee, H.P.; Zheng, H.; Luo, Z.; Li, F. Sound transmission of truss-based X-shaped inertial amplification metamaterial double panels. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 283, 109669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, S.; Liu, J.; Xia, B. Waveguides induced by replacing defects in phononic crystal. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 255, 108464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekhal, D.; Mekkakia-Maaza, N.E.; Lakhdari, A. Finite element analysis of surface elastic waveguide based on pyramidal phononic crystal. Micro Nano Lett. 2021, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, C.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Cheng, B.; Cao, J. Realization of a novel multimode waveguide with photonic band gap hopping based on coupled-resonator optical waveguide theory. Results Phys. 2023, 45, 106242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhang, G.; Chen, X.; Cong, Y.; Gu, S.; Hong, J. Elastic wave harvesting in piezoelectric-defect-introduced phononic crystal microplates. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 239, 107892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantasala, S.; Thomas, T.; Rajagopal, P. Enhanced piezoelectric energy harvesting based on sandwiched phononic crystal with embedded spheres. Phys. Scr. 2023, 98, 035029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lu, Z.; Ding, H.; Chen, L. A viscoelastic metamaterial beam for integrated vibration isolation and energy harvesting. Appl. Math. Mech. 2024, 45, 1243–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, M.S.; Halevi, P.; Dobrzynski, L.; Djafari-Rouhani, B. Acoustic band structure of periodic elastic composites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 71, 2022–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Mao, Y.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Yang, Z.; Chan, C.T.; Sheng, P. Locally Resonant Sonic Materials. Science 2000, 289, 1734–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, P.; Li, S. Phononic band gaps by inertial amplification mechanisms in periodic composite sandwich beam with lattice truss cores. Compos. Struct. 2020, 231, 111458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Jaya, M.M.; Savadkoohi, A.T.; Baguet, S. Vibration attenuation of dual periodic pipelines using interconnected vibration absorbers. Eng. Struct. 2025, 322, 119045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yao, X.; Wu, G.; Tang, L. Complete vibration band gap characteristics of two-dimensional periodic grid structures. Compos. Struct. 2021, 274, 114368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Q.; Kong, L.; Yang, X.; Shao, Z.; Li, Y. Phononic crystal pipe with periodically attached sleeves for vibration suppression. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 251, 108344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Su, X. Effect of interface/surface stress on the elastic wave band structure of two-dimensional phononic crystals. Phys. Lett. A 2012, 376, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, E.; Hosseinkhani, A.; Frangi, A.; Younesian, D.; Zega, V. A novel low-frequency multi-bandgaps metaplate: Genetic algorithm based optimization and experimental validation. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 2022, 181, 109495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.; Ruiz, R.O. Multi-objective functions for the optimization of piezoelectric metamaterials under pre-established bandwidth excitations. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 2025, 235, 112857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghpanah, B.; Ebrahimi, H.; Mousanezhad, D.; Hopkins, J.; Vaziri, A. Programmable Elastic Metamaterials. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2016, 18, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.J.; Huang, R.N.; Li, P.; Yan, H.; Dong, X.J.; Yan, Q.; Sun, Y.T.; Cheng, S.L.; Zhao, Q.X. Labyrinth acoustic metamaterials with fractal structure based on Hilbert curve. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2023, 667, 415150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oftadeh, R.; Haghpanah, B.; Vella, D.; Boudaoud, A.; Vaziri, A. Optimal Fractal-Like Hierarchical Honeycombs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 104301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, X.; Luo, Z.; Liu, J.; Xia, B. Hilbert fractal acoustic metamaterials with negative mass density and bulk modulus on subwavelength scale. Mater. Des. 2019, 180, 107911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liu, Y.; Liang, T. Band structures in Sierpinski triangle fractal porous phononic crystals. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2016, 498, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.L.; Yang, H.Y.; Ding, Q.; Yan, Q.; Sun, Y.T.; Xin, Y.J.; Wang, L. Low Frequency Band Gap and Wave Propagation Properties of a Novel Fractal Hybrid Metamaterial. Phys. Status Solidi B 2022, 259, 2200257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, H.; Zeng, Z. H-fractal seismic metamaterial with broadband low-frequency bandgaps. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2018, 51, 105104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Dong, T.; Hao, T.; Wang, J. Study of Fractal Honeycomb Structural Mechanics Metamaterial Vibration Bandgap Characteristics. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2024, 12, 909–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yin, J.H.; Zhu, X.J.; Wang, K.; Zhang, S.k.; Cao, L.; Guo, P.Y.; Liu, Y. Investigation and optimal design of band gap tunability in fractal phononic crystals. Acta Acust. 2025, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.H.M.S.; Dal Poggetto, V.F.; Beli, D.; Fabro, A.T.; Arruda, J.R.F. Investigating the stochastic dispersion of 2D engineered frame structures under symmetry of variability. J. Sound. Vib. 2022, 541, 117292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Lu, X.; Shi, L. Novel applications of local optimization semi-Cartesian grid for the complex band structure analysis of phononic crystals. Appl. Math. Model. 2023, 121, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.K.; Guo, W.; Cui, Y.M.; Wang, Y.F.; Laude, V.; Wang, Y.S. Attenuation of Lamb waves in coupled-resonator viscoelastic waveguide. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 285, 109790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakes, R. Foam Structures with a Negative Poisson’s Ratio. Science 1987, 235, 1038–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Wang, Y.; Kang, Z. Auxetic Kirigami Metamaterials upon Large Stretching. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 19190–19198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldi, K.; Reis, P.M.; Willshaw, S.; Mullin, T. Negative Poisson’s Ratio Behavior Induced by an Elastic Instability. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, N.; Mauko, A.; Ulbin, M.; Krstulović-Opara, L.; Ren, Z.; Vesenjak, M. Development and characterisation of novel three-dimensional axisymmetric chiral auxetic structures. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 17, 2701–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.J.; Ashby, M.F. The Mechanics of Two-Dimensional Cellular Materials. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1982, 382, 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowski, K.W. Constant thermodynamic tension Monte Carlo studies of elastic properties of a two-dimensional system of hard cyclic hexamers. Mol. Phys. 1987, 61, 1247–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, K.W. Two-dimensional isotropic system with a negative poisson ratio. Phys. Lett. A 1989, 137, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.E. Auxetic polymers: A new range of materials. Endeavour 1991, 15, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, G.W. Composite materials with poisson’s ratios close to—1. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1992, 40, 1105–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, T.C.T.; Chen, T. Poisson’s ratio for anisotropic elastic materials can have no bounds. Q. J. Mech. Appl. Math. 2005, 58, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, G.N.; Greer, A.L.; Lakes, R.S.; Rouxel, T. Poisson’s ratio and modern materials. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakes, R.S.; Huey, B. Poisson’s Ratio beyond the Classically Allowable Range in Chiral Isotropic Elastic Materials: Effect of k and Experiment. Phys. Status Solidi B 2023, 261, 2300411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderson, A.; Wojciechowski, K.W. Preface: Auxetic materials and anomalous systems. Phys. Status Solidi B 2005, 242, 499–500. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Han, Q.; Ma, N.; Li, C. Design and reinforcement-learning optimization of re-entrant cellular metamaterials. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 191, 111071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, S.; Wang, R.; Xia, R. Design methodology for functional gradient star-shaped honeycomb with enhanced impact resistance and energy absorption. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 108020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Cao, Y.; Sun, D.Q.; Nie, C.R.; Wang, Z.J. In-Plane Dynamic Cushioning Performance of Concave Hexagonal Honeycomb Cores. Shock Vib. 2024, 2024, 9978340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, E.; Lee, I.S.; Kim, D.; Lee, H.; Jang, W.D.; Lah, M.S.; Min, S.K.; Choe, W. Metal-organic framework based on hinged cube tessellation as transformable mechanical metamaterial. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.C. An Anisotropic Auxetic 2D Metamaterial Based on Sliding Microstructural Mechanism. Materials 2019, 12, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozniak, A.A.; Wojciechowski, K.W. Poisson’s ratio of rectangular anti-chiral structures with size dispersion of circular nodes. Phys. Status Solidi B Basic Solid State Phys. 2014, 251, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizzi, L.; Attard, D.; Gatt, R.; Pozniak, A.A.; Wojciechowski, K.W.; Grima, J.N. Influence of translational disorder on the mechanical properties of hexachiral honeycomb systems. Compos. Part B Eng. 2015, 80, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Geometric Parameters | Thickness b (m) | Angle β (°) | Unit Cell Length a (m) | Fractal Ratio α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Values | 0.004 | 30 | 0.1 | 1/5 |

| Material Properties | Young’s Modulus E (Pa) | Poisson’s Ratio υ | Density ρ (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Values | 2.2 E9 | 0.394 | 1100 |

| Various Order FRHMs | The Bounding Frequencies of Considered Stop Bands | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | |

| 1st order | (0.0602, 0.074) | (0.0881, 0.1247) | (0.1326, 0.2870) | (0.394, 0.4145) | (0.6131, 0.6246) | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| 2nd order | (0.0358, 0.0464) | (0.0556, 0.0594) | (0.0664, 0.0898) | (0.0902, 0.0957) | (0.0958, 0.1219) | (0.1282, 0.1415) | (0.1577, 0.1704) | (0.2610, 0.2634) | \ |

| 3rd order | (0.0171, 0.0019) | (0.0264, 0.052) | (0.0525, 0.0837) | (0.0846, 0.0927) | (0.0996, 0.1023) | (0.1055, 0.1109) | (0.1289, 0.1314) | (0.1358, 0.1389) | (0.1523, 0.1592) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Chen, S.; Lin, W.; Lin, Y. Study on the Complex Band Structure and Auxetic Behavior of Fractal Re-Entrant Honeycomb Metamaterials. Materials 2025, 18, 5695. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245695

Li J, Chen S, Lin W, Lin Y. Study on the Complex Band Structure and Auxetic Behavior of Fractal Re-Entrant Honeycomb Metamaterials. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5695. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245695

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jingru, Siyu Chen, Wei Lin, and Yuzhang Lin. 2025. "Study on the Complex Band Structure and Auxetic Behavior of Fractal Re-Entrant Honeycomb Metamaterials" Materials 18, no. 24: 5695. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245695

APA StyleLi, J., Chen, S., Lin, W., & Lin, Y. (2025). Study on the Complex Band Structure and Auxetic Behavior of Fractal Re-Entrant Honeycomb Metamaterials. Materials, 18(24), 5695. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245695