Unexpected Enhancement of High-Cycle Fatigue Property in Hot-Rolled DP600 Steel via Grain Size Tailoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

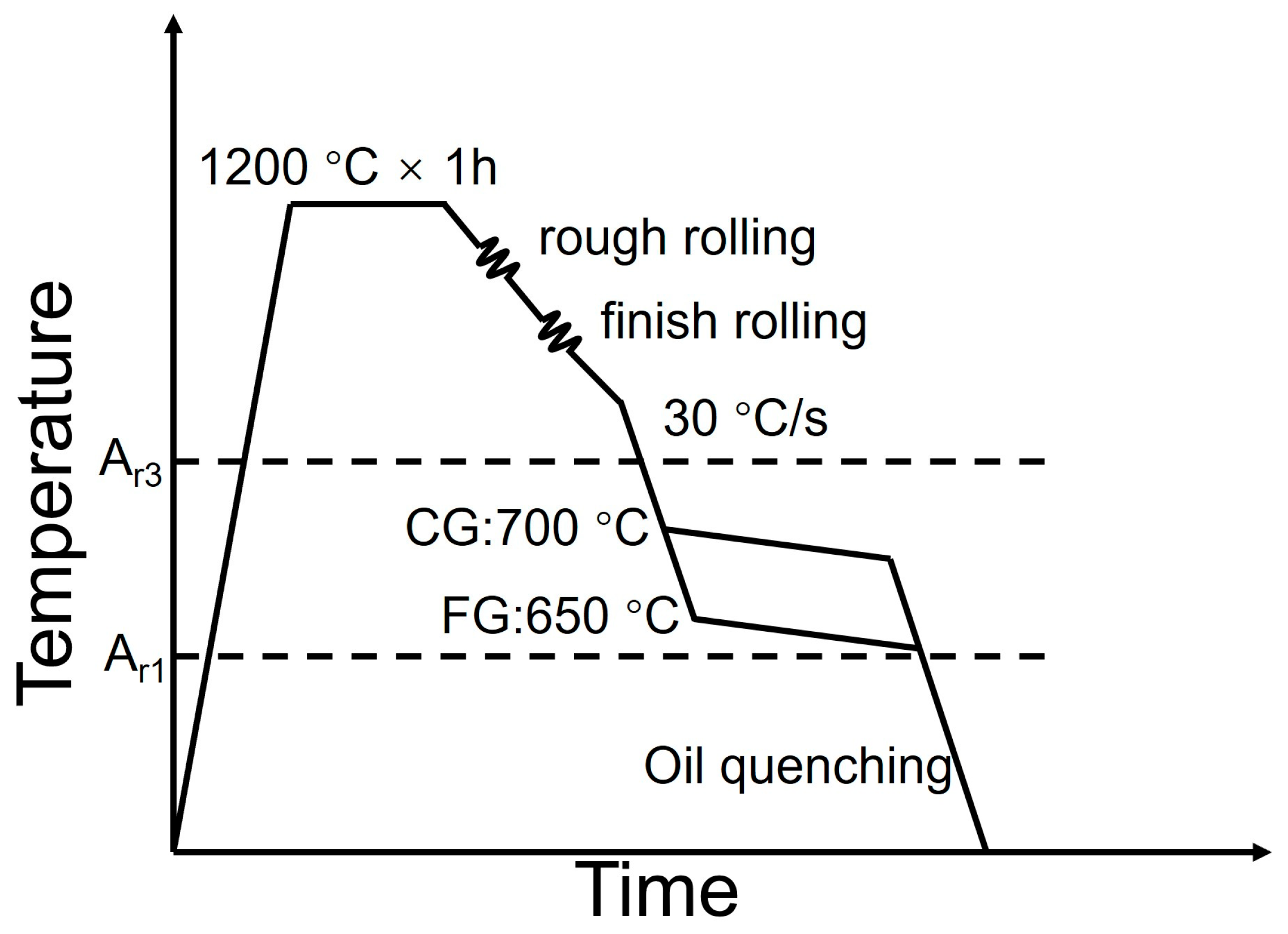

2.1. Material Preparation

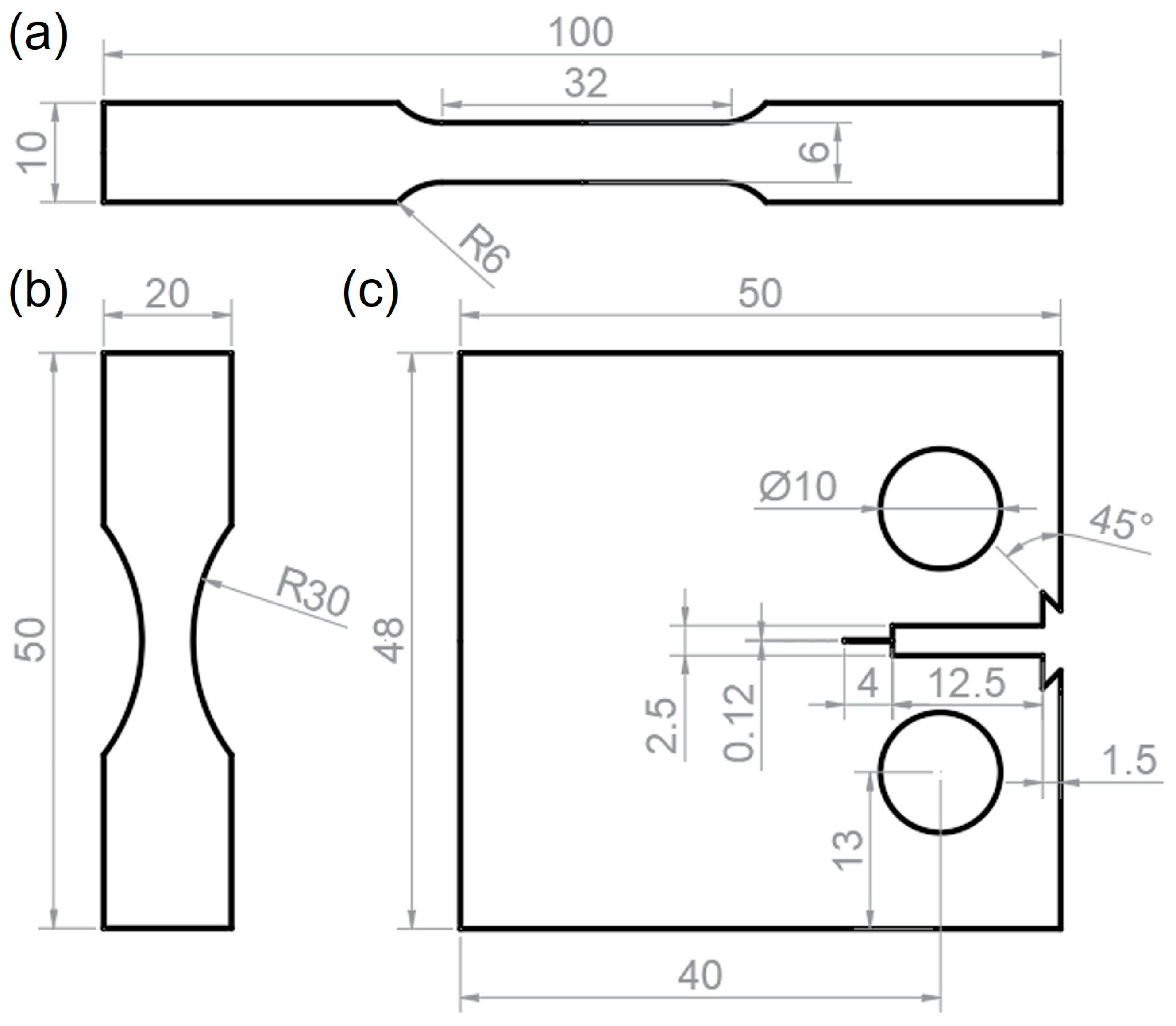

2.2. Tensile Testing and Microstructure Characterization

2.3. High-Cycle Fatigue and Fatigue Crack Growth Testing

3. Results and Discussion

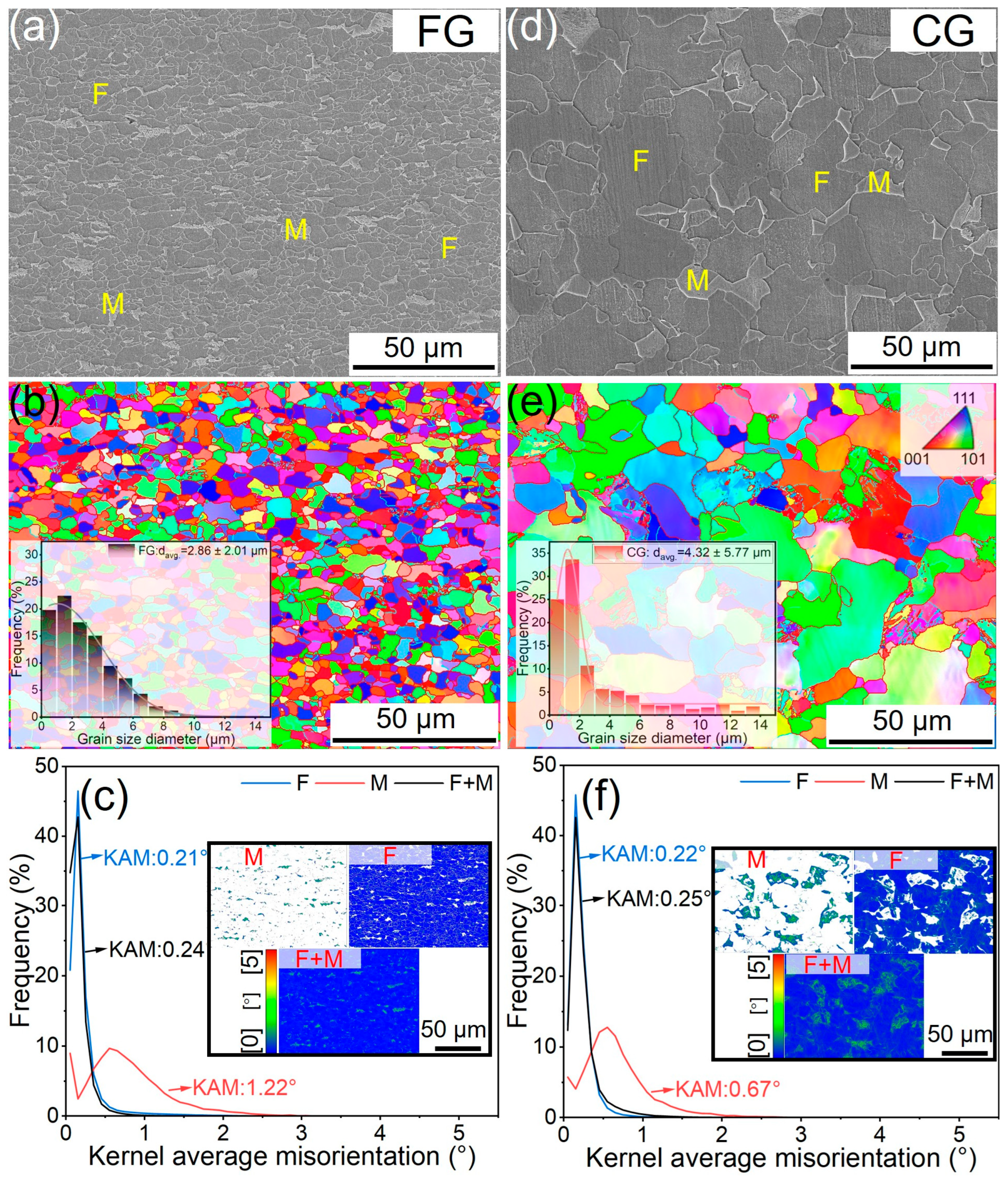

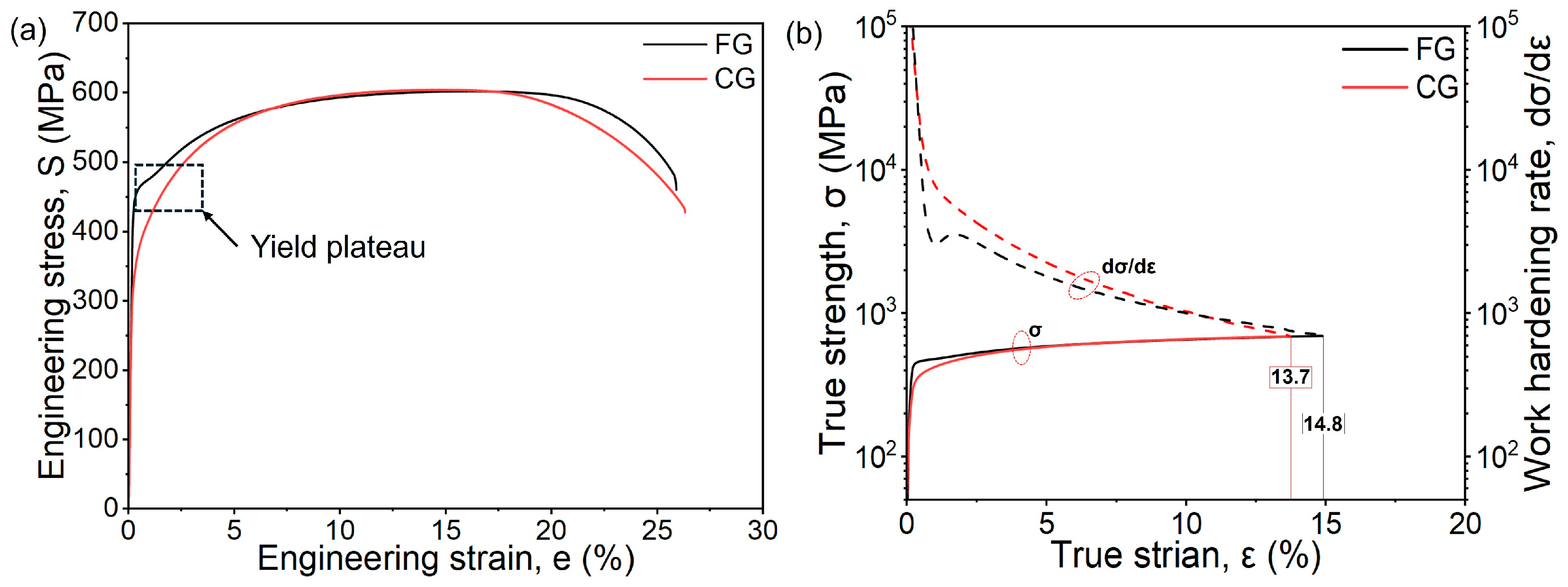

3.1. Effect of TMCP on Microstructure and Mechanical Property of DP Steels

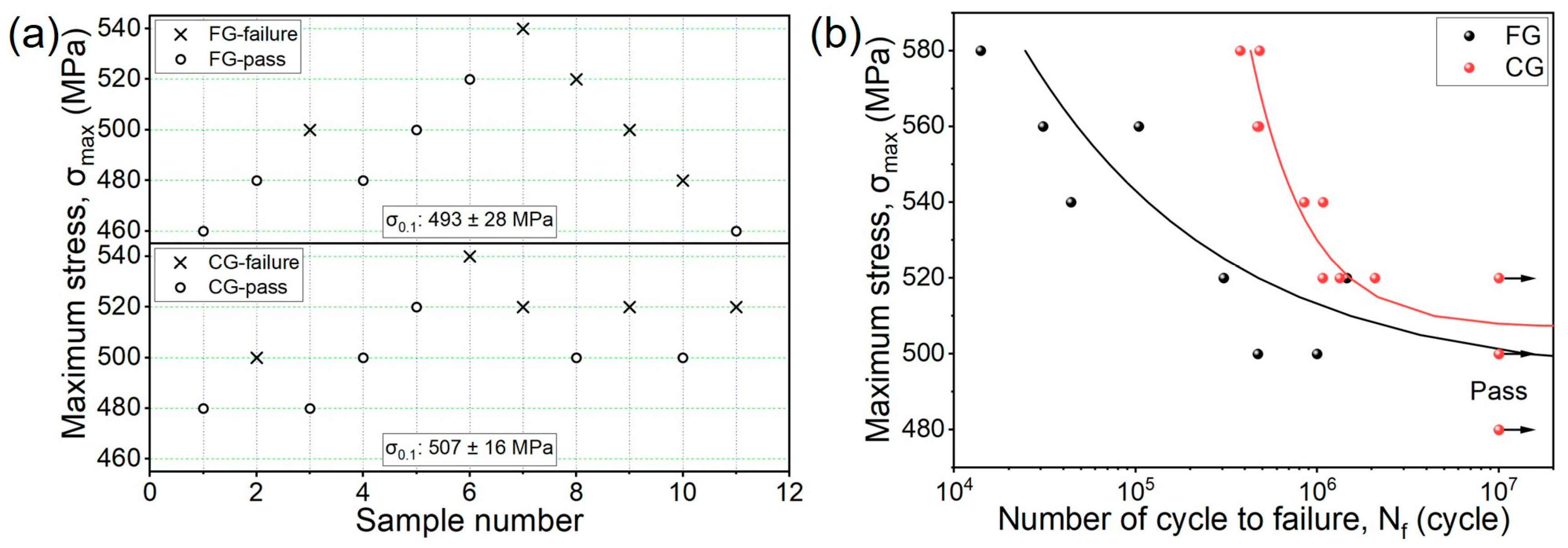

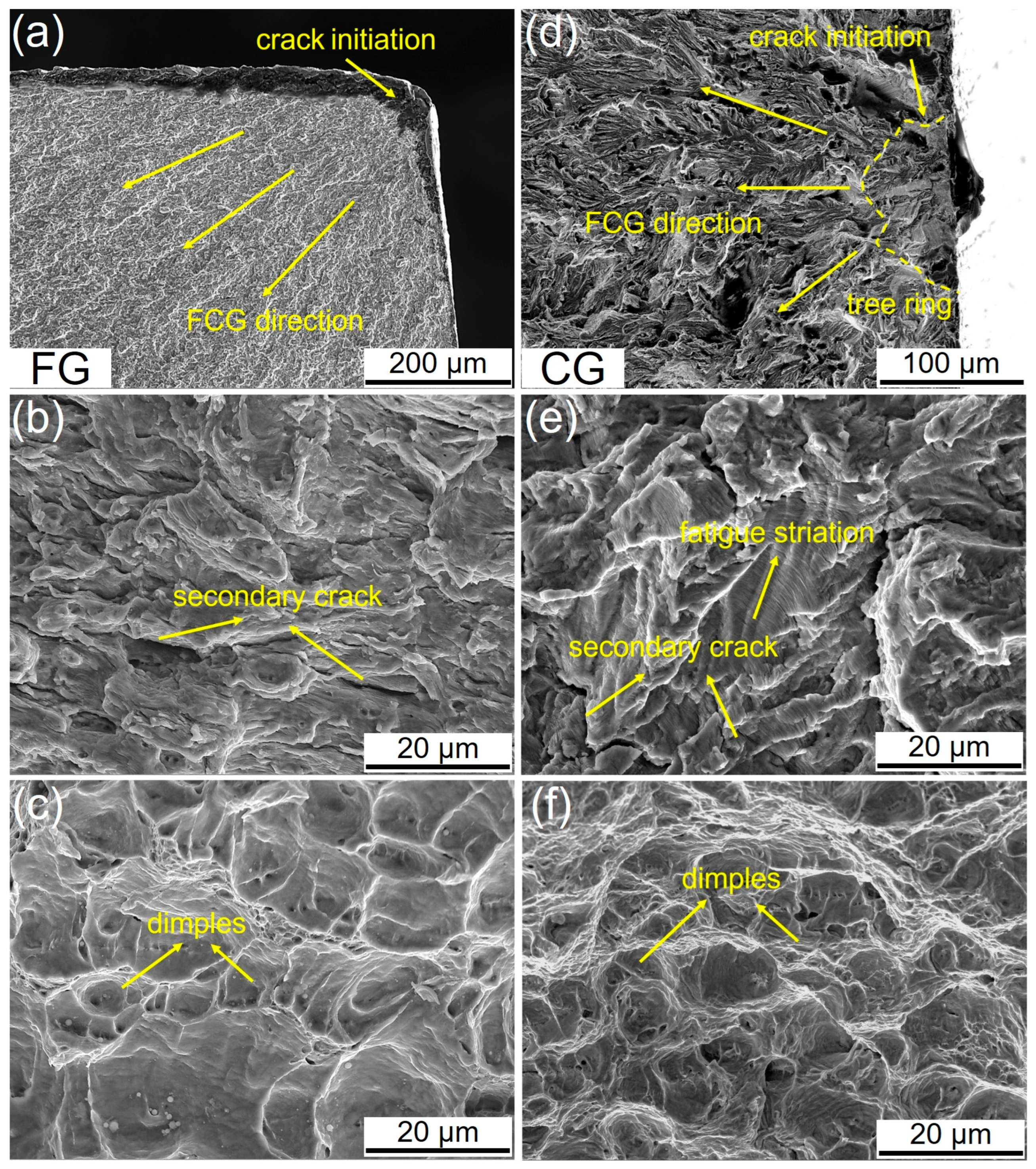

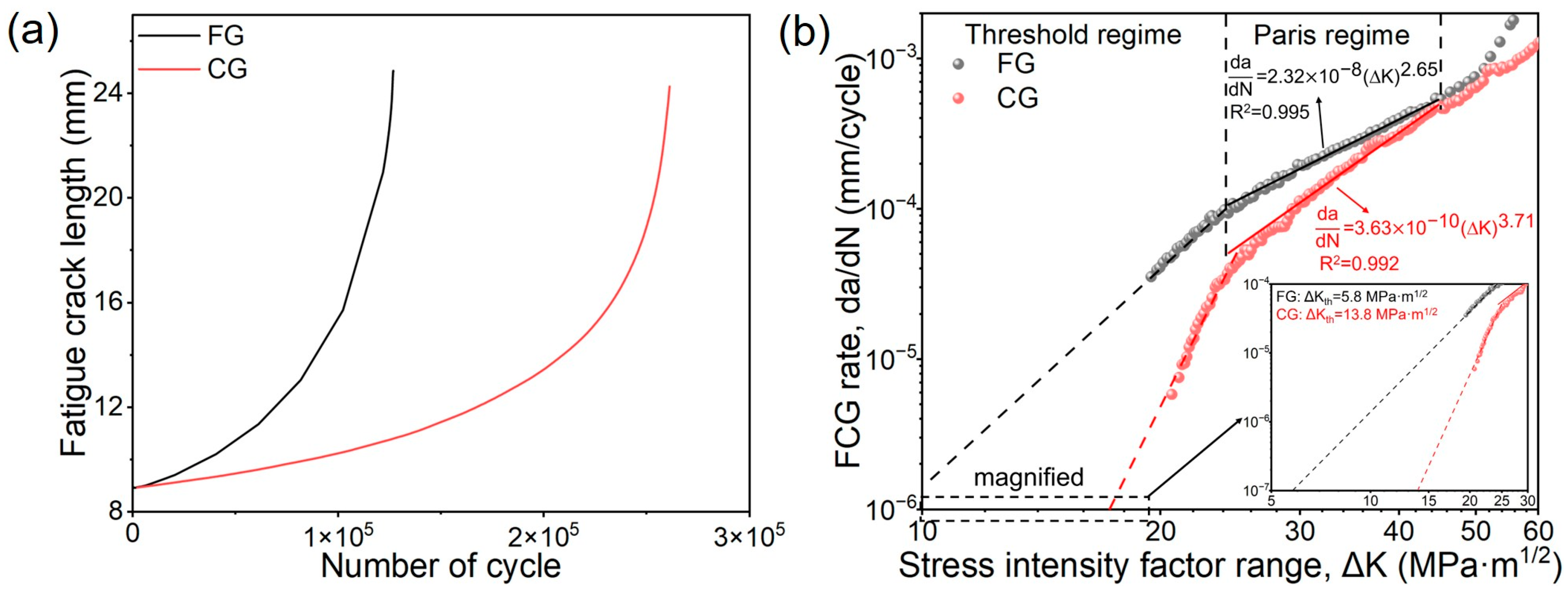

3.2. HCF Test and FCG Behavior of DP Steels

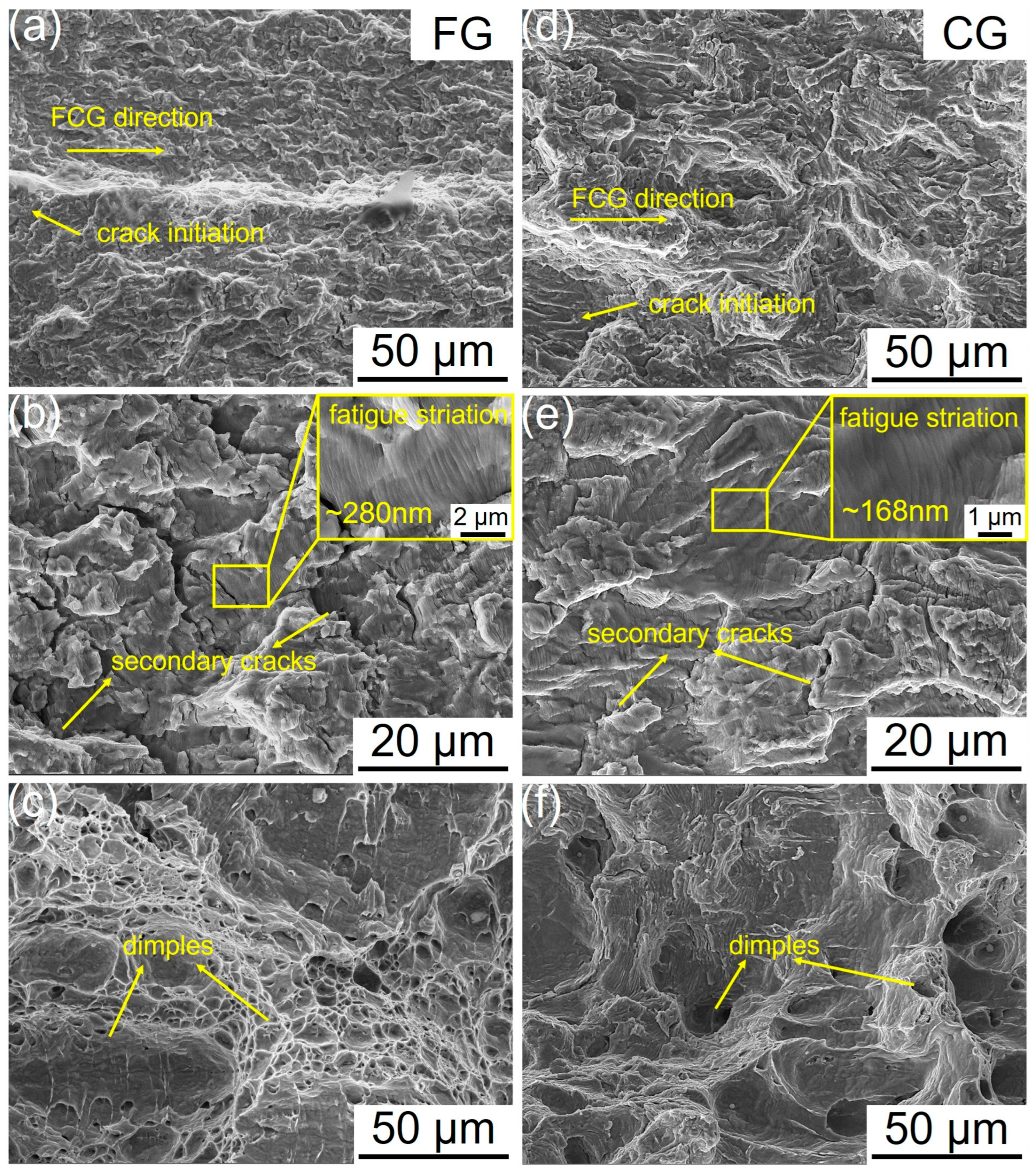

3.3. Effect of Grain Size on FCG Thresholds of FG- and CG-DP Steels

3.4. Effect of Grain Size on FCG Behavior of FG- and CG-DP Steels in Paris Regime

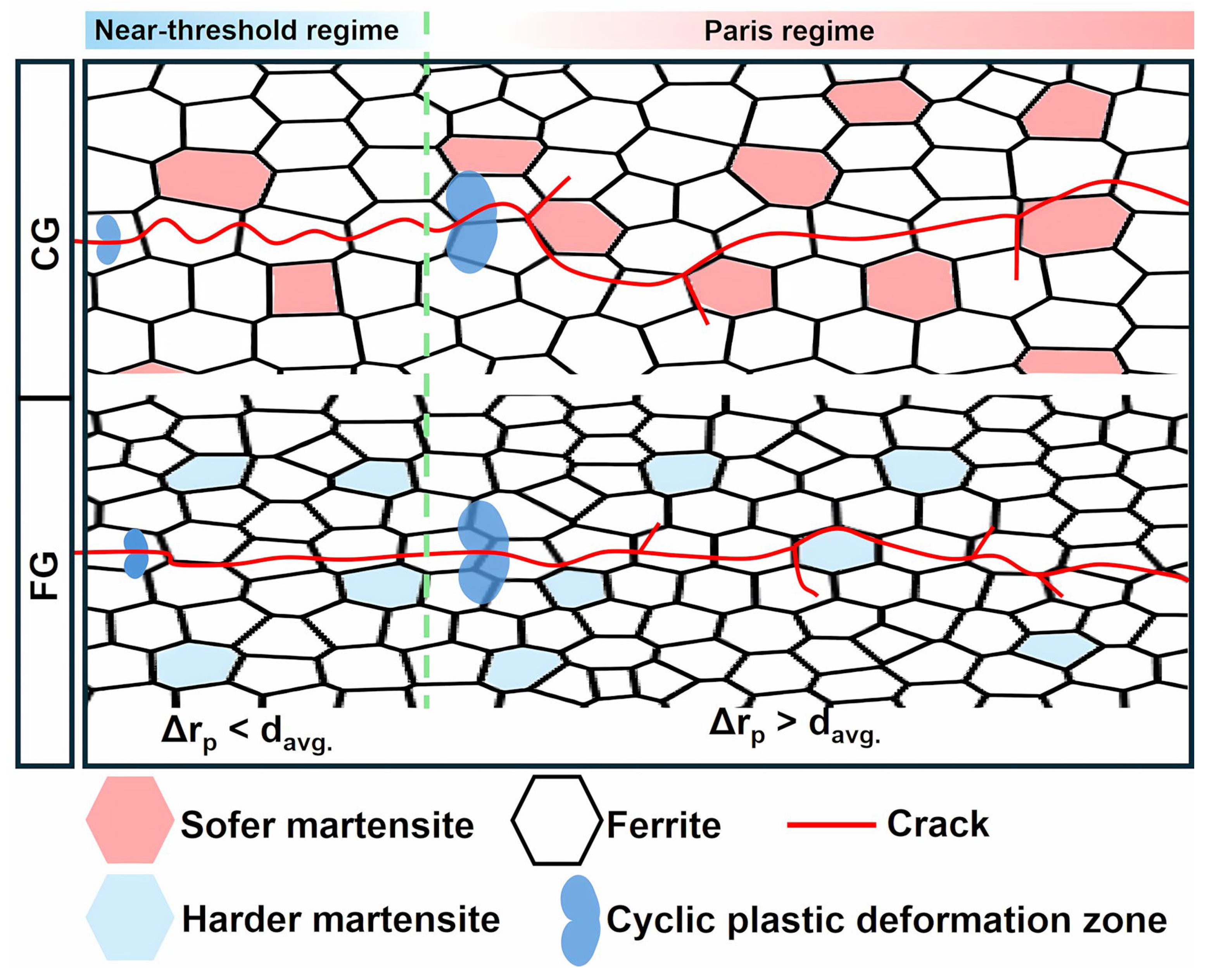

3.5. FCG Behavior Model of FG- and CG-DP Steels

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The FG-DP steel has finer ferrite grains (~2 μm) and a lower martensite volume fraction (~6%), while the CG-DP steel show coarser ferrite grains (~4 μm) and a higher martensite content (~14%). These samples exhibit nearly identical tensile strength due to synergistic effect of grain refinement strengthening and hard martensite strengthening.

- (2)

- The CG steel exhibits a slightly higher fatigue strength of 507 MPa, compared to 493 MPa for the FG steel. More notably, under higher stress amplitudes, the fatigue life of the CG sample became nearly an order of magnitude longer than that of the FG sample, indicating a significant microstructural influence on FCG behavior.

- (3)

- In the near-threshold regime, Δrp is smaller than davg.. Under such conditions, crack growth is primarily governed by dislocation slip. In the CG-sample, the longer mean free path for dislocation motion facilitates cross-slip within the grain interior, leading to frequent crack deflection. This results in enhanced roughness-induced crack closure, which contributes to a higher ΔKth in the CG steel. In contrast, the restricted dislocation motion in the FG sample results in a relatively straight crack path with limited deflection, thereby reducing the crack closure effect and resulting in a lower ΔKth.

- (4)

- In the Paris regime, Δrp exceeds davg., and crack propagation becomes influenced by the DP microstructure. The CG steel, with its higher martensite content and larger martensite size, exhibits more frequent and pronounced crack deflection. This increased crack path tortuosity effectively reduces the local driving force (ΔK), leading to a lower crack growth rate in the CG sample compared to the FG counterpart.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vermeij, T.; Mornout, C.J.A.; Rezazadeh, V.; Hoefnagels, J.P.M. Martensite plasticity and damage competition in dual-phase steel: A micromechanical experimental–numerical study. Acta Mater. 2023, 254, 119020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.; Ding, C.; Liu, Z.; Jia, X.; Chen, H.; Gong, N.; Wang, Y.; Cheng Cheh, D.T.A.N.; Misra, R.D.K.; Wu, H. Achieving high strength and high ductility of dual-phase steel via alternating lamellar microstructure. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 892, 146072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, L.; Liang, Z.; Huang, M.; Peng, Z.; Gao, J.; Luo, Z. Towards ultra-high strength dual-phase steel with excellent damage tolerance: The effect of martensite volume fraction. Int. J. Plast. 2023, 170, 103778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasan, C.C.; Diehl, M.; Yan, D.; Bechtold, M.; Roters, F.; Schemmann, L.; Zheng, C.; Peranio, N.; Ponge, D.; Koyama, M.; et al. An Overview of Dual-Phase Steels: Advances in Microstructure-Oriented Processing and Micromechanically Guided Design. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2015, 45, 391–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, Y.; Mazaheri, Y.; Ragheb, Z.D.; Daiy, H. Multi-stage strain-hardening behavior of dual-phase steels: A review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 3860–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.; Roy, S.; Ray, K.K. Fatigue performance of dual-phase steels for automotive wheel application. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2016, 40, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Guo, H.; Wang, S.; Liao, T.; Wu, H.; Ruan, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, X.; Mao, X. New route for fabricating low-carbon ductile martensite to optimize the stretch-flangeability of dual-phase steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 8049–8062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Effect of forging ratio on tensile properties and fatigue performance of EA4T steel. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 76, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, S.-S.; Wei, S.; Sun, C. Microstructure evolution, crack initiation and early growth of high-strength martensitic steels subjected to fatigue loading. Int. J. Fatigue 2024, 188, 108534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlikota, M.; Dogahe, K.; Schmauder, S.; Božić, Ž. Influence of the grain size on the fatigue initiation life curve. Int. J. Fatigue 2022, 158, 106562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burda, I.; Zweiacker, K.; Arabi-Hashemi, A.; Barriobero-Vila, P.; Stutz, A.; Koller, R.; Roelofs, H.; Oberli, L.; Lembke, M.; Affolter, C.; et al. Fatigue crack propagation behavior of a micro-bainitic TRIP steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 840, 142898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.B.; An, X.H.; Xue, P.; Liu, F.C.; Ni, D.R.; Xiao, B.L.; Liu, Y.D.; Ma, Z.Y. Grain size effects on high cycle fatigue behaviors of pure aluminum. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 170, 107556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.C.; Li, S.X.; Wang, Z.G.; Zhang, Z.F. General relation between tensile strength and fatigue strength of metallic materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2013, 564, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 228.1-2021; Metallic Materials—Tensile Testing—Part 1: Method of Test at Room Temperature. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- GB/T 3075-2021; Metallic Materials—Fatigue Testing—Axial Force-Controlled Method. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Li, X.; Xia, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Shang, C. Effect of austenite grain size and accelerated cooling start temperature on the transformation behaviors of multi-phase steel. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2012, 56, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Sun, X. Deformation induced ferrite transformation in low carbon steels. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2005, 9, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.J.; Li, D.Z.; Li, Y.Y. Modeling austenite decomposition into ferrite at different cooling rate in low-carbon steel with cellular automaton method. Acta Mater. 2004, 52, 1721–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Tian, Z.; Wu, H.-H.; Zhu, J.; Wang, S.; Wu, G.; Gao, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, C.; Mao, X. Microstructure evolution of austenite-to-martensite transformation in low-alloy steel via thermodynamically assisted phase-field method. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 1683–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhong, Y.; Liang, Y.L. Competition mechanisms of fatigue crack growth behavior in lath martensitic steel. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2018, 41, 2502–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazaheri, Y.; Kermanpur, A.; Najafizadeh, A. Nanoindentation study of ferrite–martensite dual phase steels developed by a new thermomechanical processing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 639, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.-h.; Fujimura, Y.; Shibata, A.; Tsuji, N. Effect of martensite hardness on mechanical properties and stress/strain-partitioning behavior in ferrite + martensite dual-phase steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 916, 147301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, H.D.; Kim, J.W.; Song, O.; Oh, D. Determination of true stress-strain curve of type 304 and 316 stainless steels using a typical tensile test and finite element analysis. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2021, 53, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wang, S.; Yu, H.; Wu, G.; Gao, J.; Wu, H.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, C.; Mao, X. Structure-property relationship in vanadium micro-alloyed TRIP steel subjected to the isothermal bainite transformation process. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 878, 145208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, S.; Li, X.; Gao, J.; Zhao, H.; Wang, S.; Yang, T.; Liu, S.; Han, X.; Mao, X. Cluster mediated high strength and large ductility in a strip casting micro-alloyed steel. Acta Mater. 2024, 276, 120102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Di, H.; Deng, Y.; Misra, R.D.K. Effect of martensite morphology and volume fraction on strain hardening and fracture behavior of martensite–ferrite dual phase steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 627, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weibull, W. A Statistical Representation of Fatigue Failures in Solids; Elanders: Göteborg, Sweden, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, G.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhao, C.; Jiang, F.; Li, H. Roles of microstructures in high-cycle fatigue behaviors of 42CrMo high-strength steel under near-yield mean stress. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 177, 107928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, H.; Furuya, Y.; Kasuya, T.; Enoki, M. Microstructurally small fatigue crack initiation behavior of fine and coarse grain simulated heat-affected zone microstructures in low carbon steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 832, 142363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, X.; Gao, G.; An, B.; Misra, R.D.K.; Bai, B. Relationship between non-inclusion induced crack initiation and microstructure on fatigue behavior of bainite/martensite steel in high cycle fatigue/very high cycle (HCF/VHCF) regime. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 803, 140692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, B.K.; Pavan, A.H.V.; Prakash, R.V.; Kamaraj, M. Effect of laser peening and shot peening on fatigue striations during FCGR study of Ti6Al4V. Int. J. Fatigue 2016, 93, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yin, H.; Sun, Q. Effects of grain size on fatigue crack growth behaviors of nanocrystalline superelastic NiTi shape memory alloys. Acta Mater. 2020, 195, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Liu, Q.; Cai, Z.; Sun, Q.; Huo, X.; Fan, M.; Li, K.; Pan, J. The effect of microstructure on the fatigue crack growth behavior of Ni-Cr-Mo-V steel weld metal. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 176, 107859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapetti, M.; Miyata, H.; Tagawa, T.; Miyata, T.; Fujioka, M. Fatigue crack propagation behaviour in ultra-fine grained low carbon steel. Int. J. Fatigue 2005, 27, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lados, D.A.; Apelian, D.; Jones, P.E.; Major, J.F. Microstructural mechanisms controlling fatigue crack growth in Al–Si–Mg cast alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 468–470, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, V.B.; Suresh, S.; Ritchie, R.O. Fatigue crack propagation in dual-phase steels: Effects of ferritic-martensitic microstructures on crack path morphology. Metall. Trans. A 1984, 15, 1193–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Lin, B.; Liu, T.; Deng, S.; Guo, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, D. Effect of grain structure on fatigue crack propagation behavior of Al-Cu-Li alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 148, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.P.; Miyashita, Y.; Mutoh, Y.; Morikage, Y.; Tagawa, T.; Handa, T.; Otsuka, Y. Fatigue crack deflection and branching behavior of low carbon steel under mechanically large grain condition. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 148, 106217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, A.K.; Kujawski, D. Roughness induced crack Closure: A review of key points. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2023, 125, 103897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avendaño-Rodríguez, D.; Rodriguez-Baracaldo, R.; Weber, S.; Mujica-Roncery, L. Martensite content effect on fatigue crack growth and fracture energy in dual-phase steels. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2023, 47, 884–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, S. Crack deflection: Implications for the growth of long and short fatigue cracks. Metall. Trans. A 1983, 14, 2375–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Yield Strength (MPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Total Elongation (%) | Martensite Volume Fraction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FG | 458 | 601 | 25.4 | 6 |

| CG | 355 | 604 | 25.9 | 14 |

| Samples | Coefficient of FCG Rate, C | Exponent of FCG Rate, m | Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| FG | 2.32 × 10−8 ± 1.45 × 10−9 | 2.65 ± 0.02 | 0.995 |

| CG | 3.63 × 10−10 ± 4.48 × 10−11 | 3.63 ± 0.03 | 0.992 |

| Samples | Average Deflection Angle | Actual-to-Projected Crack Length Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| FG | 37.89 ± 15.71° | 1.03 ± 0.01 |

| CG | 44.54 ± 15.45° | 1.15 ± 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Y.-A.; Yang, M.; Zhang, C.; Lu, B.; Huang, Y.; Lu, J.; Wang, S. Unexpected Enhancement of High-Cycle Fatigue Property in Hot-Rolled DP600 Steel via Grain Size Tailoring. Materials 2025, 18, 5658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245658

Song Y, Zhang C, Chen Y-A, Yang M, Zhang C, Lu B, Huang Y, Lu J, Wang S. Unexpected Enhancement of High-Cycle Fatigue Property in Hot-Rolled DP600 Steel via Grain Size Tailoring. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245658

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Yu, Cheng Zhang, Yu-An Chen, Mingyue Yang, Chao Zhang, Bing Lu, Yuhe Huang, Jun Lu, and Shuize Wang. 2025. "Unexpected Enhancement of High-Cycle Fatigue Property in Hot-Rolled DP600 Steel via Grain Size Tailoring" Materials 18, no. 24: 5658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245658

APA StyleSong, Y., Zhang, C., Chen, Y.-A., Yang, M., Zhang, C., Lu, B., Huang, Y., Lu, J., & Wang, S. (2025). Unexpected Enhancement of High-Cycle Fatigue Property in Hot-Rolled DP600 Steel via Grain Size Tailoring. Materials, 18(24), 5658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245658