Biocompatibility of Materials Dedicated to Non-Traumatic Surgical Instruments Correlated to the Effect of Applied Force of Working Part on the Coronary Vessel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Elaboration

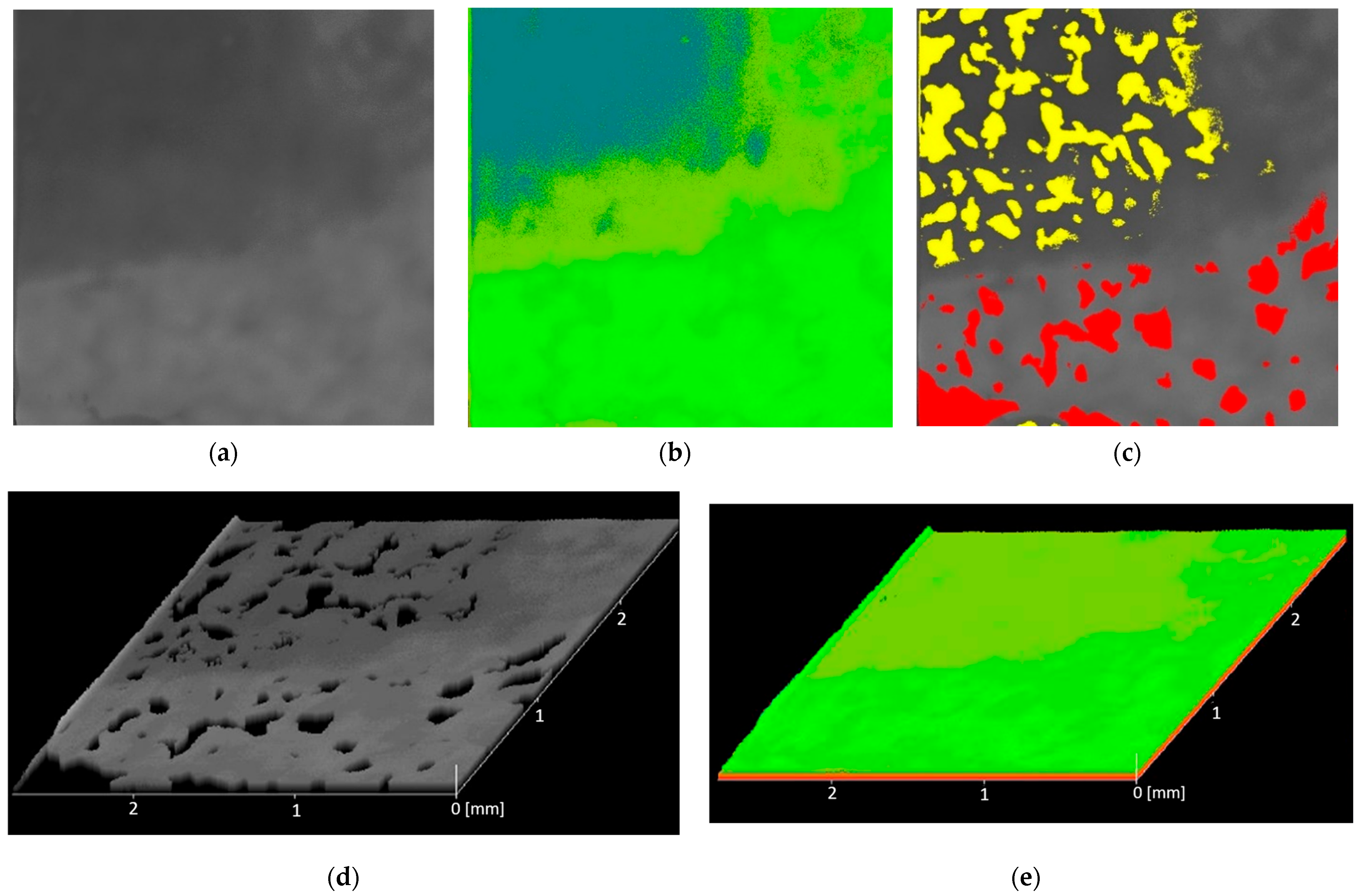

2.2. Surface Analysis

2.2.1. Topography Tests

2.2.2. Contact Angle

2.2.3. Non-Destructive Analysis of the Risk of Creating Voids in the Material in the Emergence of Acoustic Tools

2.3. Biological Evaluation of Materials Dedicated to Atraumatic Surgical Instruments

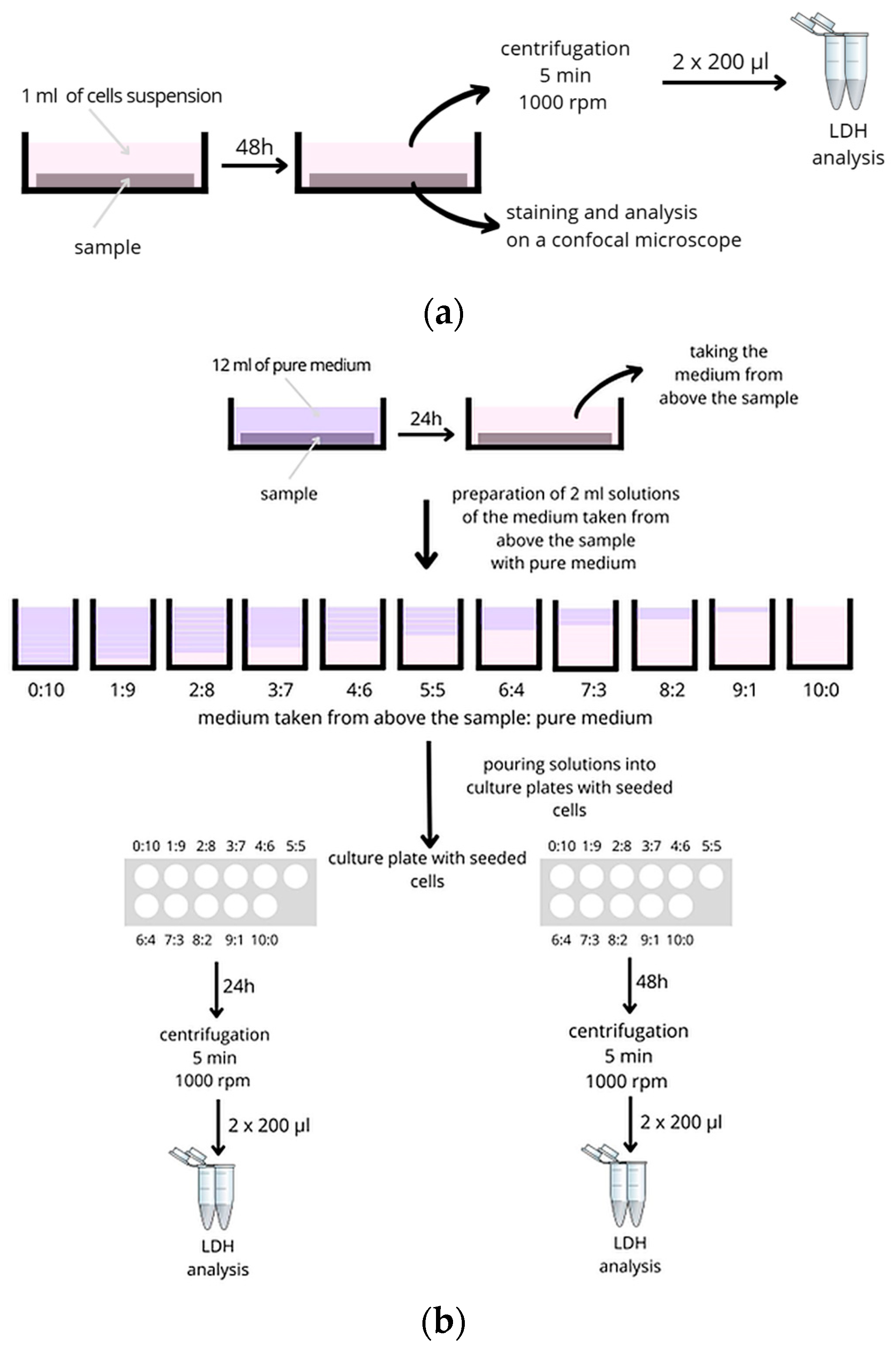

2.3.1. Cytotoxicity and Analysis of Pro-Inflammatory Molecules

- 1 mL of medium from above the sample (10:0);

- 0.9 mL of sample extract and 0.1 mL of full growth medium (9:1);

- 0.8 mL of sample extract and 0.2 mL of full growth medium (8:2);

- 0.7 mL of sample extract and 0.3 mL of full growth medium (7:3);

- 0.6 mL of sample extract and 0.4 mL of full growth medium (6:4);

- 0.5 mL of sample extract and 0.5 mL of full growth medium (5:5);

- 0.4 mL of sample extract and 0.6 mL of full growth medium (4:6);

- 0.3 mL of sample extract and 0.7 mL of full growth medium (3:7);

- 0.2 mL of sample extract and 0.8 mL of full growth medium (2:8);

- 0.1 mL of sample extract and 0.9 mL of full growth medium (1:9);

- 1 mL full growth medium (0:10).

2.3.2. Microbiology Analysis

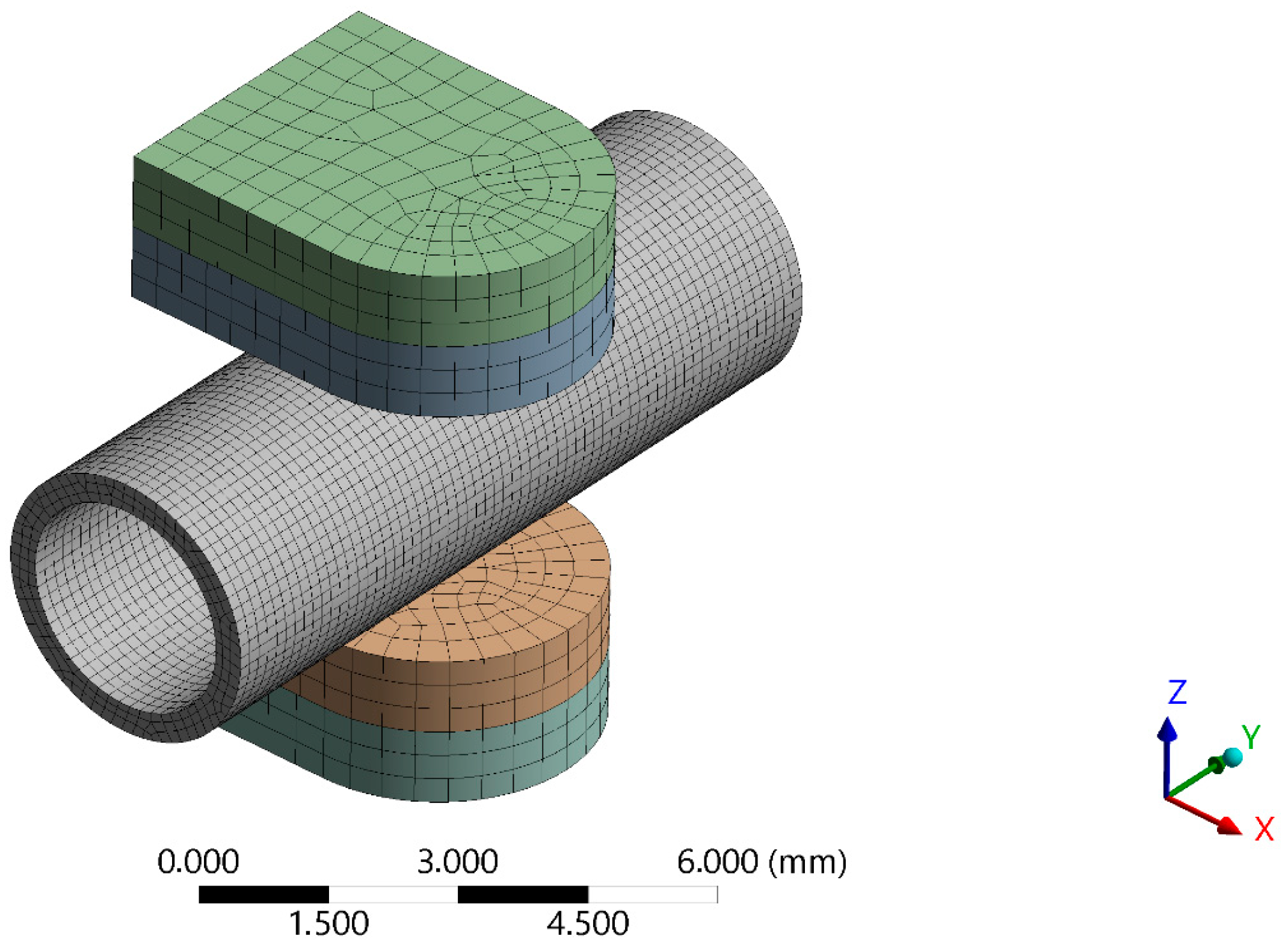

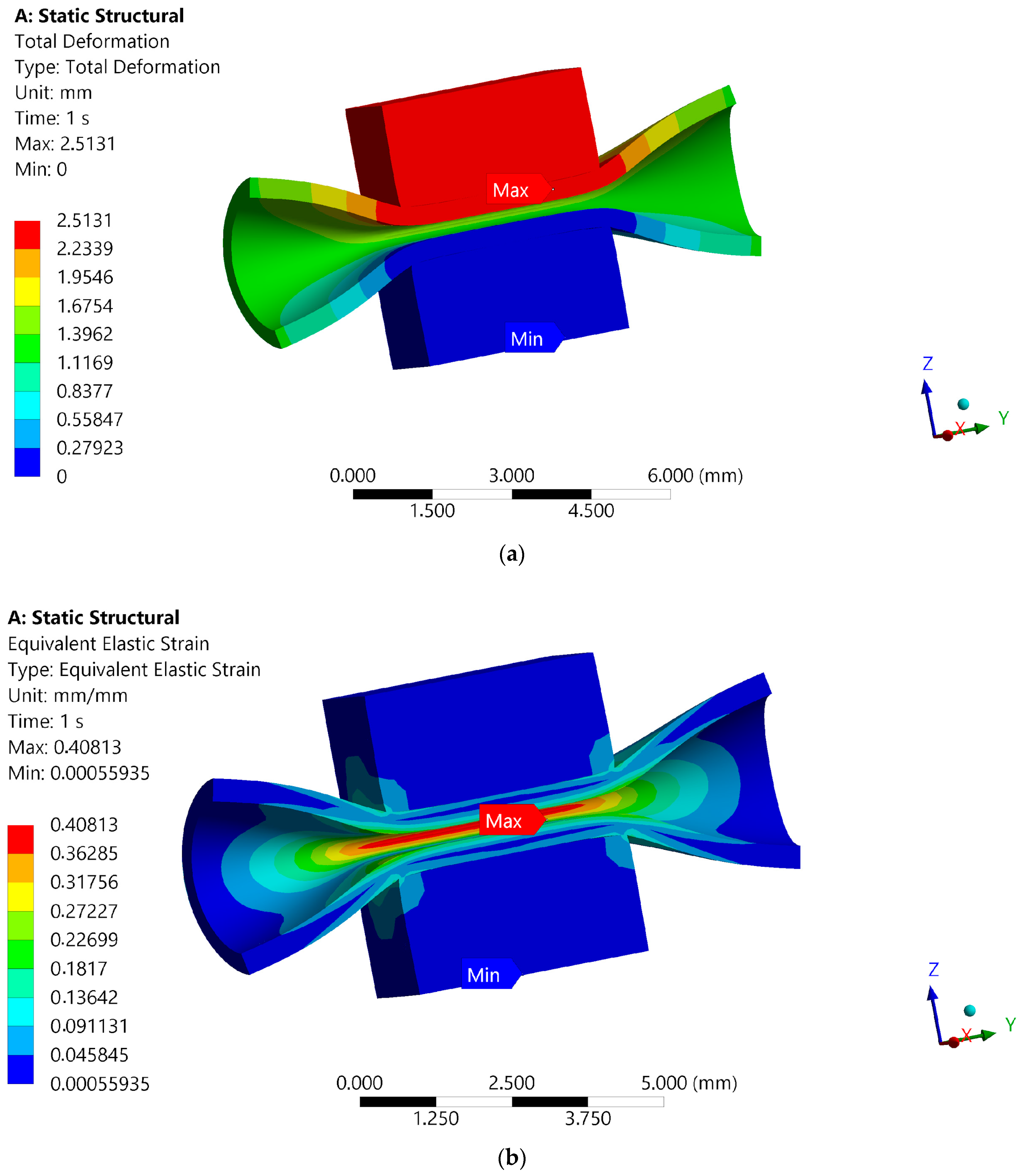

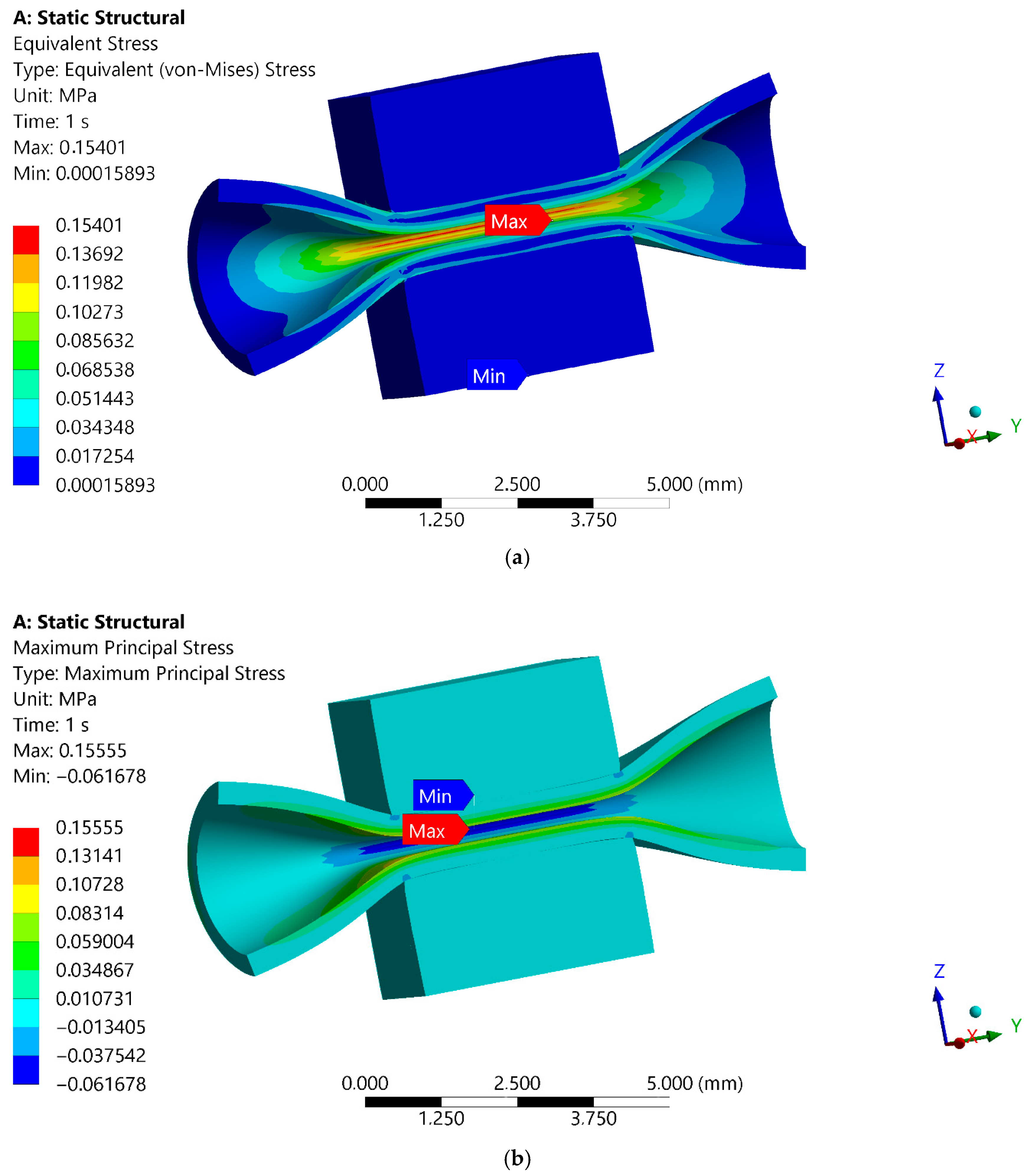

2.4. Numerical Simulation of the Maximum Forces Carried by the Blood Vessel FE Model of Blood Vessel Compression Test

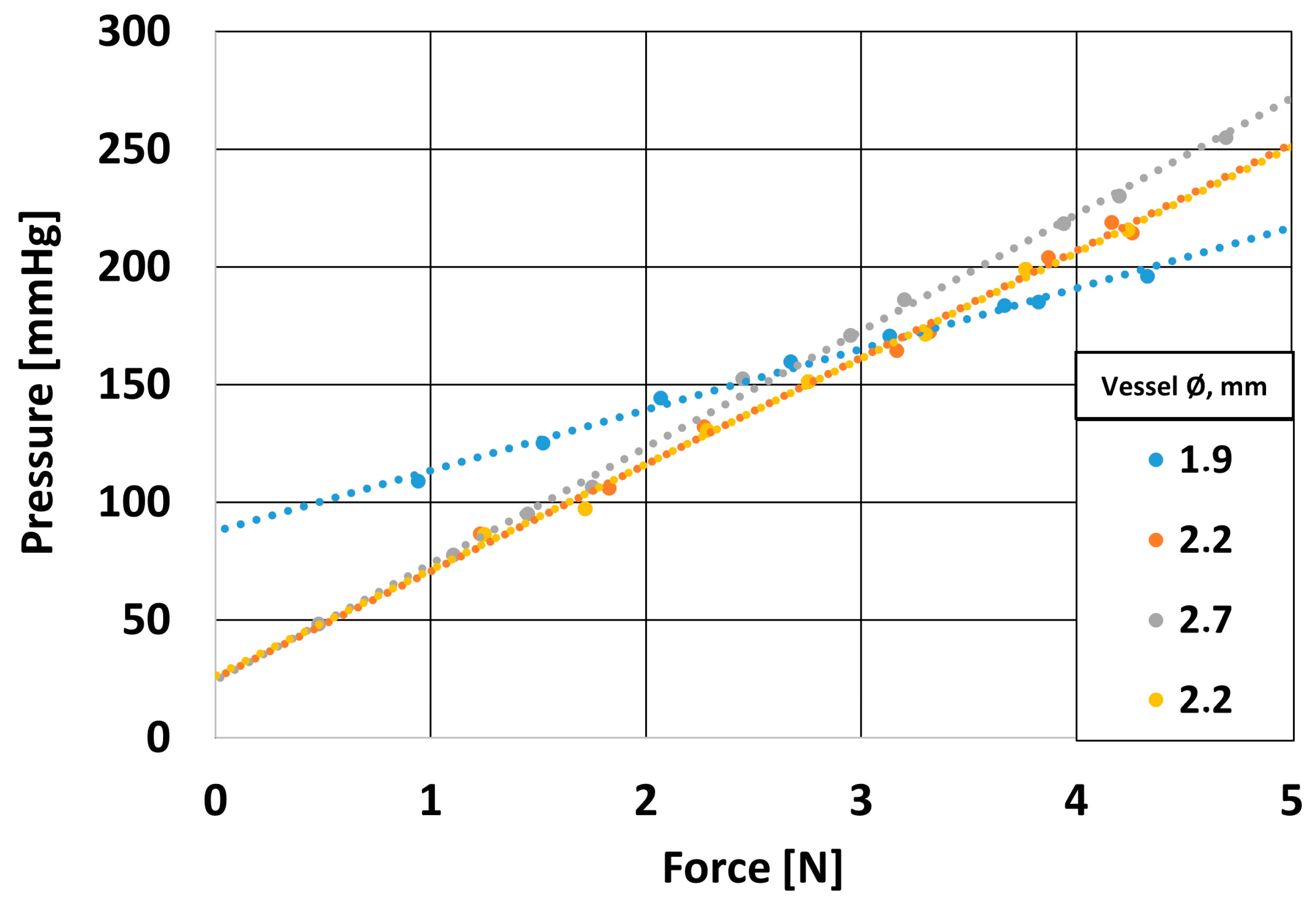

2.5. Experimental Verification of Numerical Model

2.5.1. Design of a Mechanical System to Assess the Strength of the Blood Vessel Wall

2.5.2. Histopathological Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Surface Analysis

3.1.1. Topography Tests

3.1.2. Contact Angle

3.2. Non-Destructive Analysis of the Risk of Creating Voids in the Material in the Emergence of Acoustic Tools

3.3. Biological Evaluation of Materials Dedicated to Atraumatic Surgical Instruments

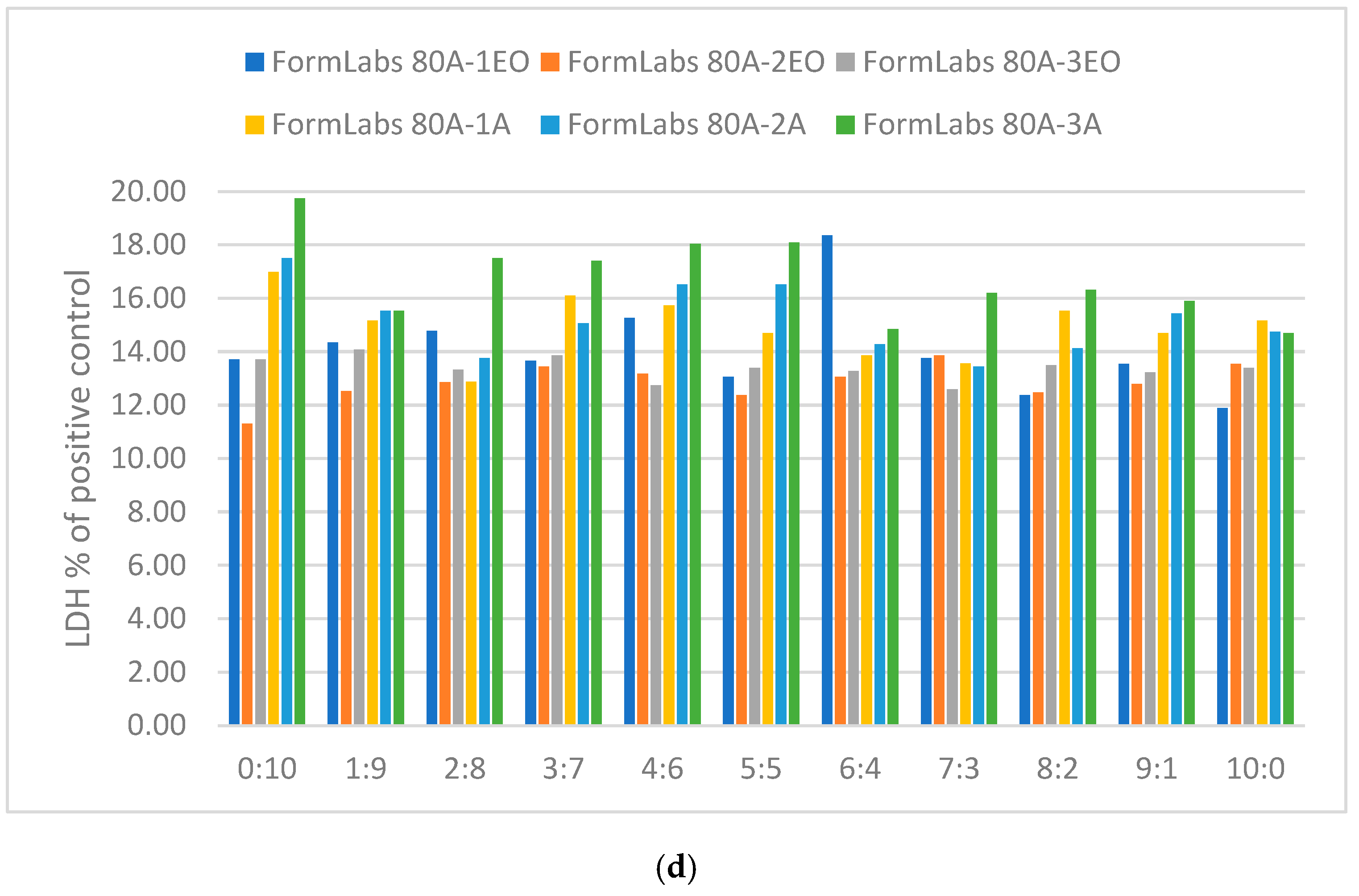

3.3.1. Cytotoxicity Lactate Dehydrogenase Levels

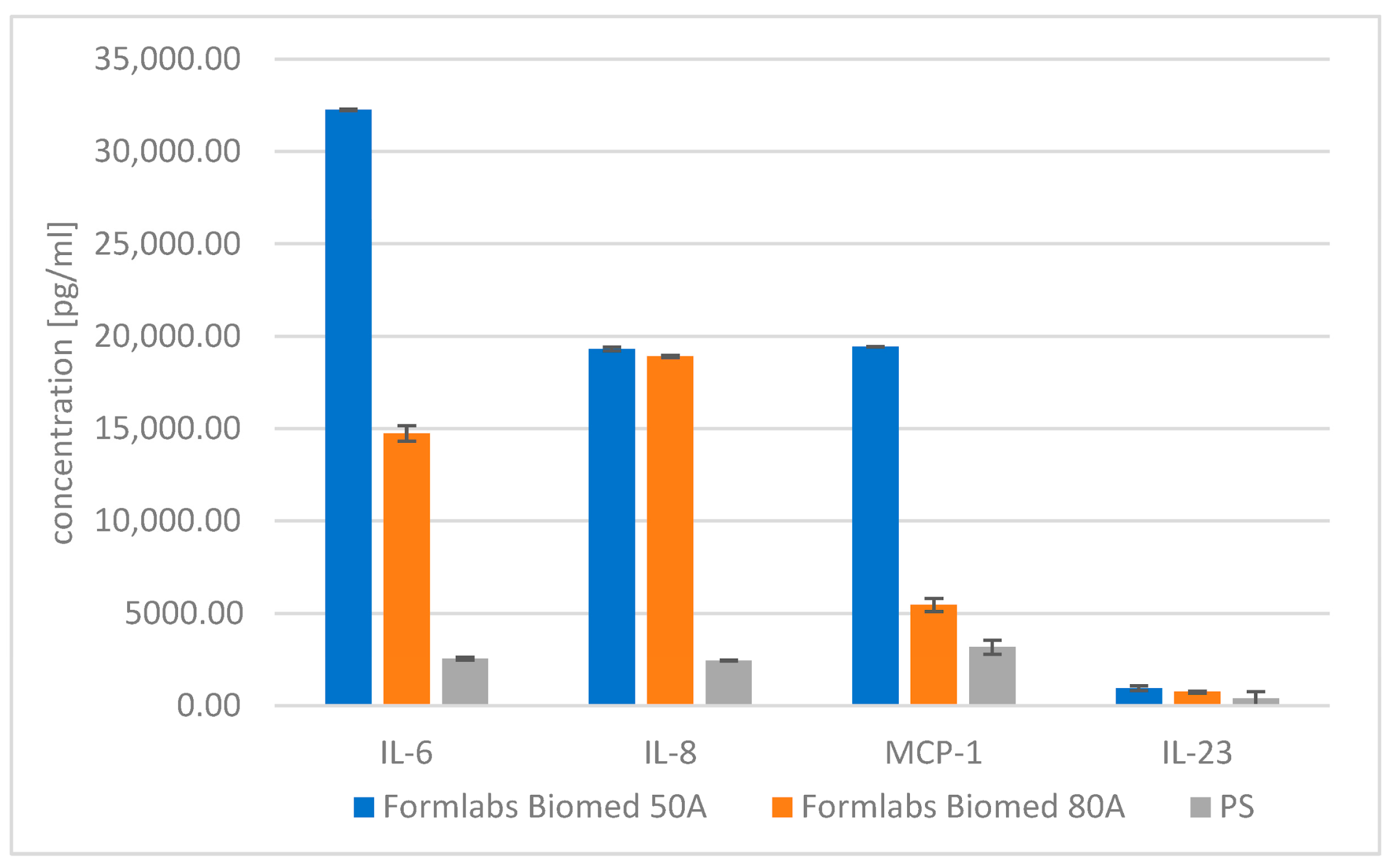

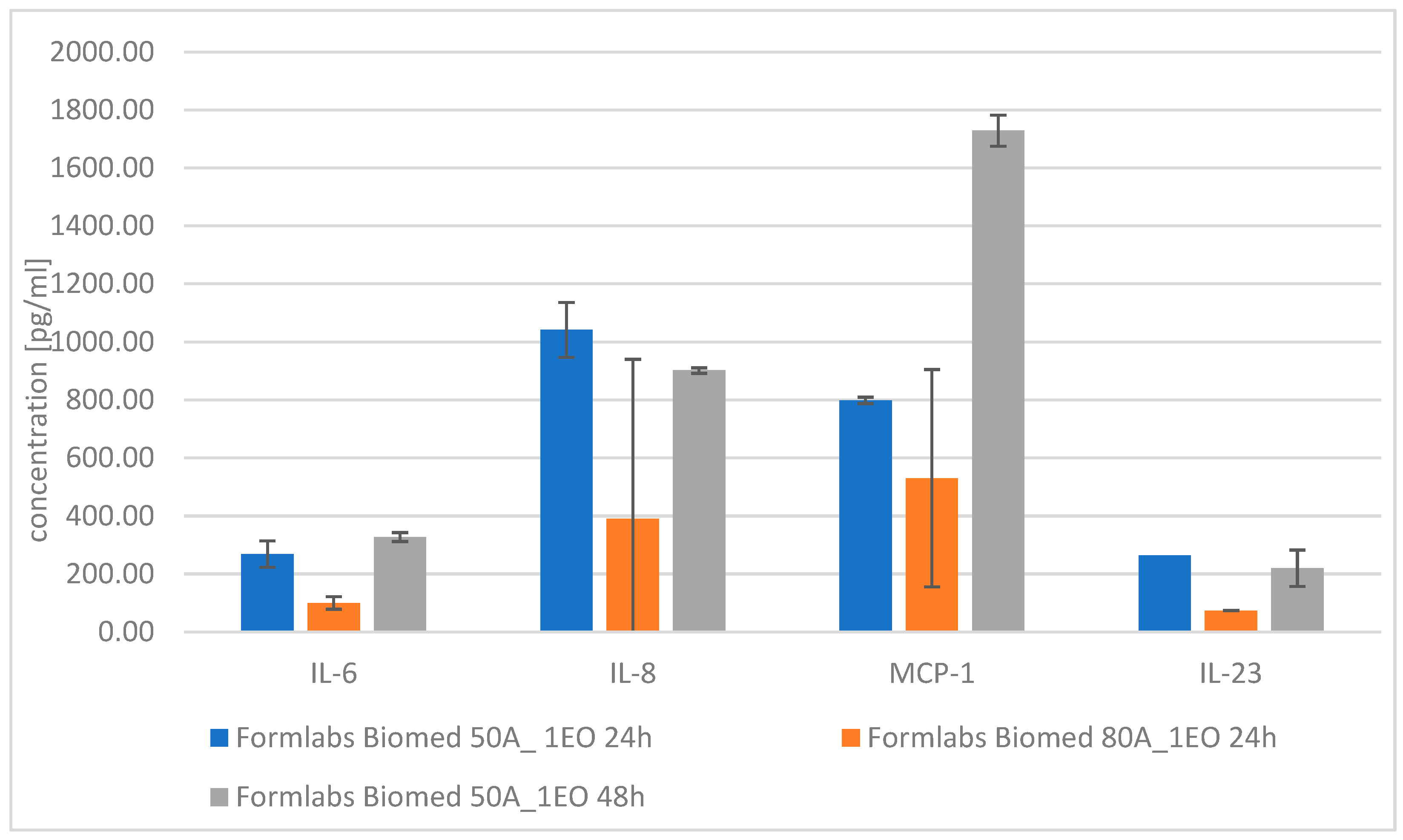

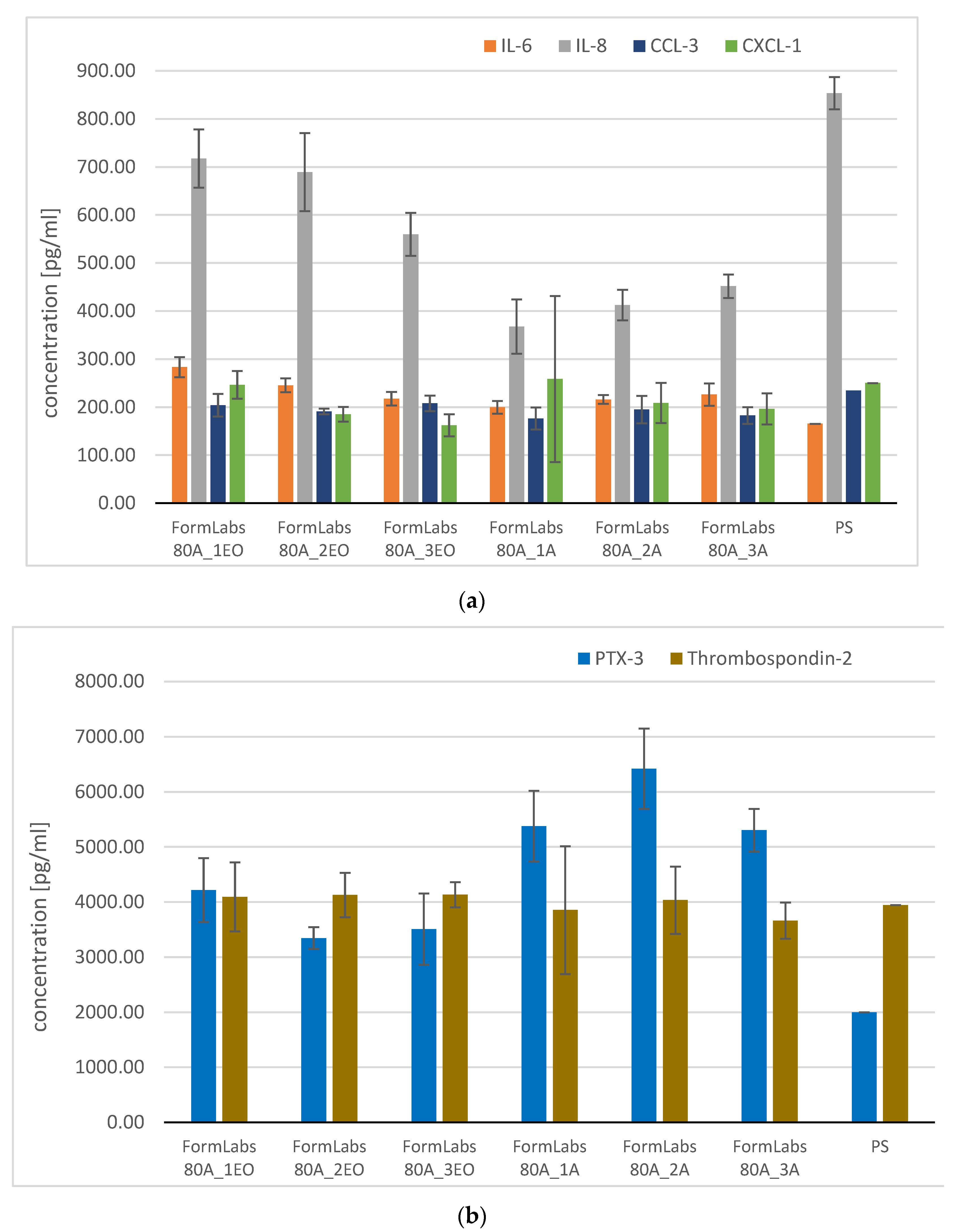

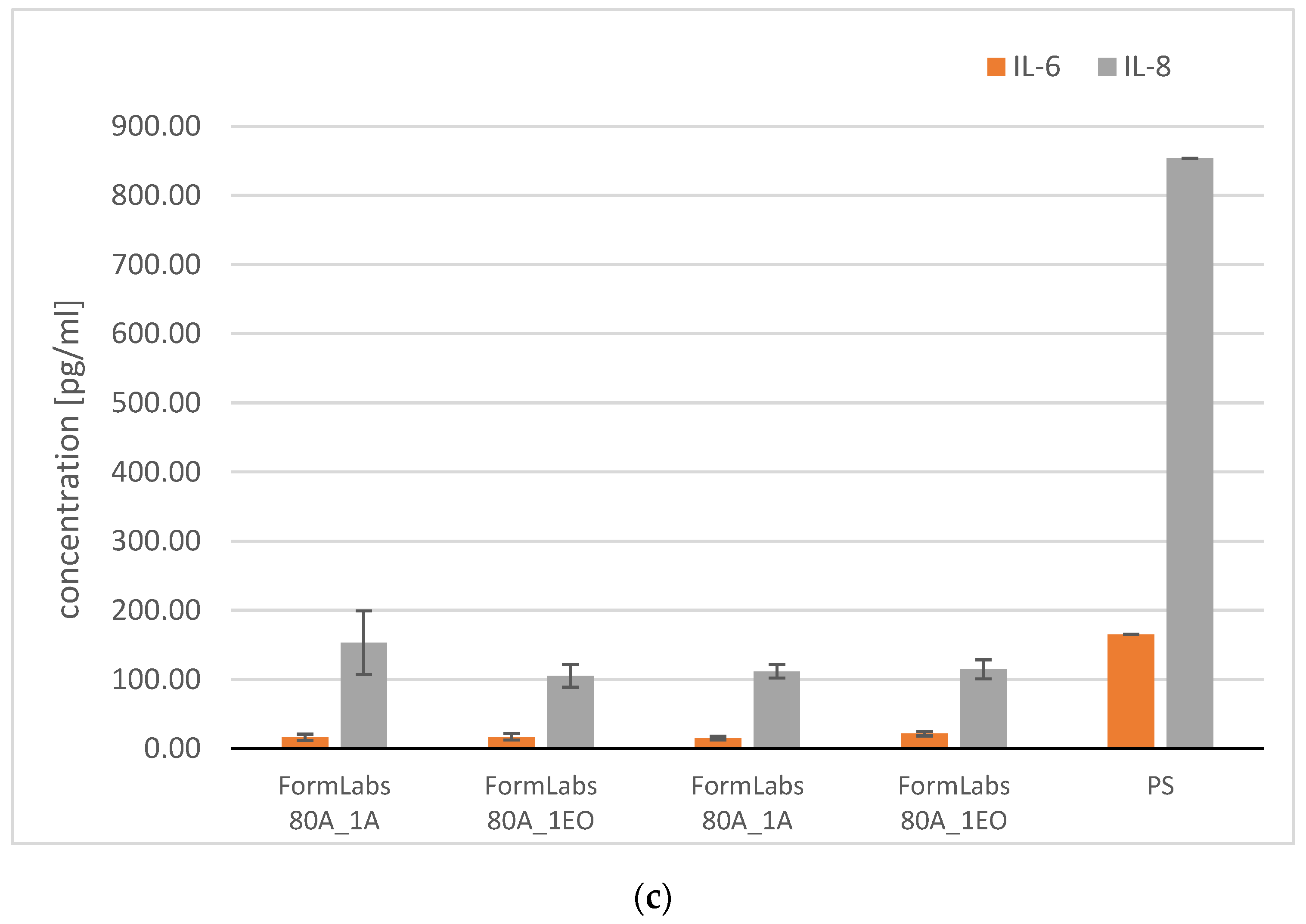

3.3.2. Analysis of Pro-Inflammatory Molecules

3.3.3. Microbiological Analysis

3.4. Numerical Simulation of the Maximum Forces Carried by the Blood Vessel

3.5. Experimental Verification of Numerical Model

3.5.1. Effect of Applied Force on Coronary Artery Pressure

3.5.2. Histopathological Analysis

4. Discussion

- The chemical makeup of Formlabs BioMed resins significantly affects their biocompatibility. Variations in surface properties and degradation behavior can lead to different cellular responses, such as adhesion and proliferation [72].

- Post-Processing Techniques

- Additional UV exposure during post-processing can improve the polymerization degree, further reducing cytotoxic effects [72].

- Biological Interactions

- The interaction between biomaterials and biological systems is complex, influenced by genetic and environmental factors, which can lead to variability in biocompatibility outcomes [75].

- Comprehensive assessment methodologies are crucial for understanding these interactions and ensuring safety in clinical applications.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSVS | Cardiovascular and thoracic surgeries |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| SMPs | Shape memory polymers |

| LSs | Lightweight structures |

| AMCs | (Anti-/meta-) chiral structures |

| AM | Additive manufacturing |

| PBF | Powder Bed Fusion |

| CVTCGI | Cardiovascular and thoracic clamping and gripping instruments |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| FISH | Fluorescence in situ hybridization |

| CLSM | Confocal laser scanning microscope |

| SEP | Surface energy parameters |

References

- Chen, Y.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J. Variable stiffness property study on shape memory polymer composite tube. Smart Mater. Struct. 2012, 21, 094021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J. Shape memory polymer composites: 4D printing, smart structures, and applications. Sci. Partner J. 2023, 2, 0234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossegger, E.; Höller, R.; Reisinger, D.; Strasser, J.; Fleisch, M.; Griesser, T.; Schlögl, S. Digital light processing 3D printing with thiol–acrylate vitrimers. Polym. Chem. 2021, 12, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madduluri, V.R.; Bendi, A.; Maniam, G.P.; Roslan, R.; Ab Rahim, M.H. Recent advances in vitrimers: A detailed study on the synthesis, properties and applications of bio-vitrimers. J. Polym. Environ. 2025, 33, 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, Z.; Filipcsei, G.; Zrínyi, M. Magnetic field sensitive functional elastomers with tunable elastic modulus. Polymer 2006, 47, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, C.; Guo, Y.; Yang, Q.; Huo, S. Vitrimer as a Sustainable Alternative to Traditional Thermoset: Recent Progress and Future Prospective. ACS Polym. Au 2025, 5, 5c00081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rylski, B.; Schmid, C.; Beyersdorf, F.; Siepe, M.J. A novel aortic clamp distributing equal pressure along the jaws. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2017, 154, 1524–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T.; Maier, A.; Kletzer, J.; Schlett, C.L.; Kondov, S.; Czerny, M.; Rylski, B.; Kreibich, M. Radiographic complicated and uncomplicated descending aortic dissections: Aortic morphological differences by CT angiography and risk factor analysis. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2024, 25, jeae030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, B.D.; Chun, M.S.; Winter, H.H. Modulus-Switching Viscoelasticity of Electrorheological Networks. Rheol. Acta 2009, 48, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R.; Sinha Ray, S. Role of Rheology in Morphology Development and Advanced Processing of Thermoplastic Polymer Materials: A Review. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 27969–28001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Hu, W.; Liu, C.; Li, S.; Niu, X.; Pei, Q. Phase-Changing Bistable Electroactive Polymer Exhibiting Sharp Rigid-to-Rubbery Transition. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Peng, Z.; Guo, Y.; Wang, H.; Plamthottam, R.; Pei, Q. Hybrid Fabrication of Prestrain-Locked Acrylic Dielectric Elastomer Thin Films and Multilayer Stacks. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2023, 2300160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amend, J.R.; Brown, E.; Rodenberg, N.; Jaeger, H.M.; Lipson, H. A Positive Pressure Universal Gripper Based on the Jamming of Granular Material. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2012, 28, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J.; Miranda, C. Design, Control, and Applications of Granular Jamming Grippers in Soft Robotics. Robotics 2025, 14, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, M.; Helps, T.; Huang, B.; Rossiter, J. 3D-Printed Ready-To-Use Variable-Stiffness Structures. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 2402–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkowski, P.; Ciemiorek, M.; Bukowiecki, H.; Bomba, P.; Zalewski, R. Mechanical Properties and Energy Absorption Characteristics of Granular Jamming Structures under Compression. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2025, 25, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surjadi, J.U.; Gao, L.; Du, H.; Li, X.; Xiong, X.; Fang, N.X.; Lu, Y. Mechanical Metamaterials and Their Engineering Applications. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2019, 21, 1800864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surjadi, J.U.; Wang, L.; Qu, S.; Aymon, B.F.G.; Ding, J.; Zhou, X.; Fan, R.; Yang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Song, X.; et al. Programmable Mechanical Metamaterials with Tunable Nonlinearity. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadt0589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousou, J.H.; Engelman, R.M. Atraumatic Vascular Clamping Techniques. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1981, 32, 515–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreibich, M.; Bavaria, J.E.; Branchetti, E.; Brown, C.R.; Chen, Z.; Khurshan, F.; Siki, M.; Vallabhajosyula, P.; Szeto, W.Y.; Desai, N.D. Contemporary Strategies for Aortic Clamping in Cardiothoracic Surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2023, 115, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, P.; Mueller, J.; Raney, J.R.; Zheng, X.; Alavi, A.H. Mechanical metamaterials and beyond. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomarah, A.; Masood, S.H.; Sbarski, I.; Faisal, B.; Gao, Z.; Ruan, D. Design and Additive Manufacturing of Mechanical Metamaterials: A Review. Virtual. Phys. Prototyp. 2020, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benke, M.R.; Kapadani, K.R.; Gawande, J.; Chikkangoudar, R.N.; Navale, V.R.; Khatode, A.L. Recent Advances in Cellular and Lattice Structures for Load-Bearing Applications. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. D 2025, 106, 477–495. [Google Scholar]

- Truszkiewicz, E.; Thalhamer, A.; Rossegger, M.; Vetter, M.; Meier, G.; Rossegger, E.; Fuchs, P.; Schlögl, S.; Berer, M.J. Thermomechanical Behavior of Additively Manufactured Polymer Metamaterials. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossegger, E.; Shaukat, U.; Moazzen, K.; Fleisch, M.; Berer, M.; Schlögl, S. Advanced Polymer Networks with Tunable Mechanical Properties. Polym. Chem. 2023, 14, 2640–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhou, J.; Liang, H.; Jiang, Z.; Wu, L. Mechanical Metamaterials with Unusual Properties: A Review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 94, 114–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roback, J.C.; Nagrath, A.; Kristipati, S.; Santangelo, C.D.; Hayward, R.C. Soft Mechanical Metamaterials with Programmable Stiffness. Soft Matter 2025, 21, 3890–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Lee, H.; Weisgraber, T.H.; Shusteff, M.; DeOtte, J.; Duoss, E.B.; Kuntz, J.D.; Biener, M.M.; Ge, Q.; Jackson, J.A.; et al. Ultralight, ultrastiff mechanical metamaterials. Science 2014, 344, 1373–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaedler, T.A.; Jacobsen, A.J.; Torrents, A.; Sorensen, A.E.; Lian, J.; Greer, J.R.; Valdevit, L.; Carter, W.B. Ultralight Metallic Microlattices. Science 2011, 334, 962–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, C.S.; Yao, D.; Xu, Z.; Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Elkins, D.; Kile, M.; Deshpande, V.; Kong, Z.; Zheng, X. Architected Materials with Extreme Energy Absorption and Recoverability Enabled by Multiscale Design. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousanezhad, D.; Haghpanah, B.; Ghosh, R.; Hamouda, A.M.; Nayeb-Hashemi, H.; Vaziri, A. Elastic Properties of Chiral, Anti-Chiral, and Hierarchical Honeycomb Auxetic Materials. Theor. Appl. Mech. Lett. 2016, 6, 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Xia, L.; Xiong, Y. Inverse Design of Mechanical Metamaterials with Tailored Nonlinear Stress–Strain Responses. Mater. Horiz. 2024, 24, d4mh00906a. [Google Scholar]

- Salam, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A. A Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-De-Alba, A.; Flores-Treviño, S.; Camacho-Ortiz, A.; Contreras-Cordero, J.F.; Bocanegra-Ibarias, P. Biofilm Formation on Medical Devices and Its Clinical Impact. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 514. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Hussein, S.; Qurbani, K.; Ibrahim, R.H.; Fareeq, A.; Mahmood, K.A.; Mohamed, M.G. Healthcare-Associated Infections: Epidemiology, Prevention, and Control. J. Med. Surg. Public Health 2024, 2, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, A.; Zahra, F. Nosocomial Infections; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Monegro, A.F.; Muppidi, V.; Regunath, H. Healthcare-Associated Infections. In Patient Safety: A Case-Based Innovative Playbook for Safer Care, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 183–198. [Google Scholar]

- Major, R.; Surmiak, M.; Kasperkiewicz, K.; Kaindl, R.; Byrski, A.; Major, Ł.; Russmueller, G.; Moser, D.; Kopernik, M.; Lackner, J.M. Antibacterial and Anti-Biofilm Properties of Surface-Modified Metallic Biomaterials. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 220, 112943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasperkiewicz, K.; Major, R.; Sypien, A.; Kot, M.; Dyner, M.; Major, Ł.; Byrski, A.; Kopernik, M.; Lackner, J.M. Surface-Driven Modulation of Bacterial Adhesion and Biofilm Formation on Biomaterials. Molecules 2021, 26, 3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 13485:2016; Medical Devices Quality Management Systems Requirements for Regulatory Purposes. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/59752.html (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- BioMed Elastic 50A Formlabs Dental. Available online: https://dental.formlabs.com/eu/store/materials/biomed-elastic-50a-resin/ (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- BioMed Flex 80A Formlabs Dental. Available online: https://dental.formlabs.com/eu/store/materials/biomed-flex-80a-resin/ (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- ASTM D7334-08; Standard Practice for Surface Wettability of Coatings, Substrates and Pigments by Advancing Contact Angle Measurement. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- PN-EN ISO 10993-5; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices Part 5: Tests for In Vitro Cytotoxicity. PKN: Warsaw, Poland, 2009.

- Xu, L.C.; Siedlecki, C.A. Protein Adsorption, Platelet Adhesion, and Surface Chemistry of Biomaterials. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 3273–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.; Guo, Z. Bioinspired Surfaces with Antibacterial and Antifouling Properties: A Review. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 2914–2929. [Google Scholar]

- Mallmann, C.; Siemoneit, S.; Schmiedel, D.; Petrich, A.; Gescher, D.M.; Halle, E.; Musci, M.; Hetzer, R.; Göbel, U.B.; Moter, A. Diagnosis of Vascular Graft Infections by Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010, 16, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopf, A.G.M.; Kursawe, L.; Schubert, S.; Moter, I.; Wiessner, A.; Sarbandi, K.; Eszlari, E.; Cvorak, A.; von Schöning, D.; Klefisch, F.-R. Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization for Rapid Diagnosis of Prosthetic and Vascular Infections. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofae716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinchuk, V.; Zinchuk, O. Quantitative Colocalization Analysis of Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy Images. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. 2008, 39, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelicci, S.; Furia, L.; Scanarini, M.; Pelicci, P.G.; Lanzanò, L.; Faretta, M. Super-Resolution Microscopy Techniques for the Study of Nanoscale Cellular Structures. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claes, E.; Atienza, J.M.; Guinea, G.V.; Rojo, F.J.; Bernal, J.M.; Revuelta, J.M.; Elices, M. Mechanical Characterization of Arterial Tissue under Compression. In Proceedings of the 2010 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, EMBC’10, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 30 August–4 September 2010; pp. 3792–3795. [Google Scholar]

- Savvopoulos, F.; Keeling, M.C.; Carassiti, D.; Fogell, N.A.; Patel, M.B.; Naser, J.; Gavara, N.; de Silva, R.; Krams, R.J.R. Biomechanics of Coronary Arteries under Physiological and Pathological Loading. Soc. Interface 2024, 21, 20230674. [Google Scholar]

- Yakovenko, A.A.; Goryacheva, I.G. Friction and Contact Mechanics of Soft Biological Tissues. Friction 2024, 12, 1042–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, M.; Saha, P. Failure Mechanisms in Biomedical Materials: A Review. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 160, 108252. [Google Scholar]

- Kolli, V.; Winkler, A.; Wartzack, S.; Marian, M. Influence of Surface Topography on Friction and Wear Behavior. Surf. Topogr. 2022, 10, 044011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolli, V.; Winkler, A.; Wartzack, S.; Marian, M. Multiscale Surface Characterization for Tribological Applications. Surf. Topogr. 2023, 11, 024005. [Google Scholar]

- Farea, A.; Çelebi, M.S. Efficient Sparse Direct Solvers for Large-Scale Linear Systems. Numer. Linear Algebra Appl. 2023, 30, e2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, R.; Martínez, M.Á.; Peña, E. Constitutive Modeling of Arterial Tissue: A Review. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1162436. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, K.K.; Lakhani, P.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, N.J. Hyperelastic Modeling of Arterial Tissue Based on Experimental Data. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 126, 105013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, K.K.; Lakhani, P.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, N.R. Comparative Study of Hyperelastic Material Models for Soft Biological Tissues. Soc. Open Sci. 2023, 10, 211301. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, M.J. Theory of Large Elastic Deformation. Appl. Phys. 1940, 11, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenträger, S.; Maurer, L.; Juhre, D.; Altenbach, H.; Eisenträger, J. Advanced Hyperelastic Material Models for Soft Matter. Acta Mech. 2025, 236, 1899–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivlin, R.S. Large Elastic Deformations of Isotropic Materials. RSPTA 1948, 241, 379–397. [Google Scholar]

- Grabs, C.; Wirges, W. Recent Advances in Hyperelastic Material Modeling. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.07120. [Google Scholar]

- Böl, M.; Reese, S. Micromechanical Modelling of Skeletal Muscles Based on the Hill-Type Model. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2006, 43, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.L.S.; Uchida, T.K. Computational Modeling of Soft Biological Tissues: Challenges and Perspectives. J. Biomech. Eng. 2023, 145, 071002. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, R. W Non-Linear Elastic Deformations. Eng. Anal. 1984, 1, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.-S.; Le Roux de Bretagne, O.; Grasso, M.; Brighton, J.; StLeger-Harris, C.; Carless, O. Design Strategies for Bioinspired Mechanical Metamaterials. Designs 2023, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM B265-15; Standard Specification for Titanium and Titanium Alloy Strip, Sheet, and Plate. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASME SB 265-17; Specification for Titanium and Titanium Alloy Strip, Sheet, and Plate. ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2017.

- ISO 25178-70:2014; Geometrical Product Specification (GPS)—Surface Texture: Areal, Part 70: Material Measures. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/57688.html (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Gadhave, D.; Jaju, S. Design and Analysis of Metamaterial-Based Structures for Variable Stiffness Applications. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Innovations and Challenges in Emerging Technologies, ICICET 2024, Nagpur, India, 7–8 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigalevičiūtė, G.; Baltriukienė, D.; Bukelskienė, V.; Malinauskas, M. Biocompatibility Evaluation of Additively Manufactured Polymer Microstructures for Biomedical Applications. Coatings 2020, 10, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravoitytė, B.; Varnelytė, G.; Lukša-Žebelovič, J.; Tracevičius, S.; Burokas, A.; Baltriukienė, D.; Servienė, E.J. Bacterial Biofilm Formation and Microbial Safety Aspects of Insect-Based Feed Ingredients Insects Food Feed. J. Insects Food Feed 2025, 11, 1398. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.F. Biocompatibility Pathways: From Concept to Clinical Translation. Biomaterials 2023, 296, 122077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaraju, H.; McAtee, A.M.; Akman, R.E.; Verga, A.S.; Bocks, M.L.; Hollister, S.J. Effects of Ethylene Oxide Sterilization on the Mechanical and Biological Performance of Elastomeric Biomaterials. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B. Appl. Biomater. 2023, 111, 958–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Type | Sample Condition |

|---|---|

| Formlabs Biomed Elastic 50A | Before sterilization—Formlabs 50A |

| After 1 cycle of ethylene oxide (EO) sterilization—Formlabs 50A_1EO | |

| After 2 cycles of ethylene oxide (EO) sterilization—Formlabs 50A_2EO | |

| After 3 cycles of ethylene oxide (EO) sterilization—Formlabs 50A_3EO | |

| After 1 cycle of autoclave (A) sterilization—Formlabs 50A_1A | |

| After 2 cycles of autoclave (A) sterilization—Formlabs 50A_2A | |

| After 3 cycles of autoclave (A) sterilization—Formlabs 50A_3A | |

| Formlabs Biomed Flex 80A | Before sterilization—Formlabs 80A |

| After 1 cycle of ethylene oxide (EO) sterilization—Formlabs 80A_1EO | |

| After 2 cycles of ethylene oxide (EO) sterilization—Formlabs 80A_2EO | |

| After 3 cycles of ethylene oxide (EO) sterilization—Formlabs 80A_3EO | |

| After 1 cycle of autoclave (A) sterilization—Formlabs 80A_1A | |

| After 2 cycles of autoclave (A) sterilization—Formlabs 80A_2A | |

| After 3 cycles of autoclave (A) sterilization—Formlabs 80A_3A |

| Parameter [µm] | BioMed 50A | BioMed 80A |

|---|---|---|

| Sq | 3.52 ± 0.45 | 3.20 ± 0.65 |

| Sp | 13.92 ± 2.87 | 11.62 ± 2.18 |

| Sv | 8.64 ± 1.92 | 10.82 ± 1.77 |

| Sz | 22.54 ± 2.66 | 22.44 ± 3.14 |

| Sa | 2.71 ± 0.30 | 2.56 ± 0.55 |

| One Cycle of Sterilization | Two Cycles of Sterilization | Three Cycles of Sterilization | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| θ [°] | ||||||||

| Distilled water | PBS | Diiodomethane | Distilled water | PBS | Diiodomethane | Distilled water | PBS | Diiodomethane |

| 104.6 ± 7.7 | 97.7 ± 9.8 | 50.3 ± 4.1 | 107.1 ± 4.6 | 102.5 ± 8.8 | 52.8 ± 3.8 | 102.5 ± 7.8 | 98.5 ± 7.8 | 51.4 ± 7.6 |

| One Cycle of Sterilization | Two Cycles of Sterilization | Three Cycles of Sterilization | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| θ [°] | ||||||||

| Distilled water | PBS | Diiodomethane | Distilled water | PBS | Diiodomethane | Distilled water | PBS | Diiodomethane |

| 87.6 ± 3.1 | 90.2 ± 5.6 | 48.9 ± 4.3 | 84.9 ± 4.6 | 84.2 ± 6.4 | 47.6 ± 5.1 | 73.0 ± 6.4 | 67.6 ± 6.4 | 47.4 ± 6.2 |

| One Cycle of Sterilization | Two Cycles of Sterilization | Three Cycles of Sterilization | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| θ [°] | ||||||||

| Distilled water | PBS | Diiodomethane | Distilled water | PBS | Diiodomethane | Distilled water | PBS | Diiodomethane |

| 95.3 ± 7.3 | 90.2 ± 4.9 | 51.0 ± 7.3 | 91.1 ± 4.2 | 85.3 ± 5.4 | 52.5 ± 4.9 | 90.1 ± 2.9 | 85.3 ± 1.6 | 51.2 ± 1.7 |

| One Cycle of Sterilization | Two Cycles of Sterilization | Three Cycles of Sterilization | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| θ [°] | ||||||||

| Distilled water | PBS | Diiodomethane | Distilled water | PBS | Diiodomethane | Distilled water | PBS | Diiodomethane |

| 87.4 ± 5.0 | 84.7 ± 3.5 | 47.6 ± 5.2 | 88.7 ± 5.3 | 84.1 ± 4.0 | 48.0 ± 5.5 | 84.3 ± 4.4 | 81.5 ± 6.3 | 47.1 ± 4.1 |

| One Cycle of Sterilization | Two Cycles of Sterilization | Three Cycles of Sterilization | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFE According to the Owens-Wendt Model [mJ/m2] | ||||||||

| γ_S | γ_S^d | γ_S^p | γ_S | γ_S^d | γ_S^p | γ_S | γ_S^d | γ_S^p |

| 34.1 | 34.1 | 0.0 | 32.7 | 32.7 | 0.0 | 35.3 | 33.6 | 1.7 |

| One Cycle of Sterilization | Two Cycles of Sterilization | Three Cycles of Sterilization | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFE According to the Owens-Wendt Model [mJ/m2] | ||||||||

| γ_S | γ_S^d | γ_S^p | γ_S | γ_S^d | γ_S^p | γ_S | γ_S^d | γ_S^p |

| 37.0 | 34.9 | 2.1 | 37.1 | 35.4 | 1.8 | 35.7 | 42.9 | 7.2 |

| One Cycle of Sterilization | Two Cycles of Sterilization | Three Cycles of Sterilization | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFE According to the Owens-Wendt Model [mJ/m2] | ||||||||

| γ_S | γ_S^d | γ_S^p | γ_S | γ_S^d | γ_S^p | γ_S | γ_S^d | γ_S^p |

| 34.0 | 33.1 | 0.9 | 35.4 | 33.4 | 2.0 | 36.3 | 32.8 | 3.5 |

| One Cycle of Sterilization | Two Cycles of Sterilization | Three Cycles of Sterilization | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFE According to the Owens-Wendt Model [mJ/m2] | ||||||||

| γ_S | γ_S^d | γ_S^p | γ_S | γ_S^d | γ_S^p | γ_S | γ_S^d | γ_S^p |

| 35.8 | 33.4 | 2.4 | 35.5 | 33.5 | 2.0 | 36.3 | 32.8 | 3.5 |

| IL-6 | IL-8 | MCP-1 | IL-23 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct cytotoxicity | Formlabs Biomed 50A | 32,257.14 ± 30.18 | 19,317.75 ± 109.95 | 19,434.29 ± 5.34 | 947.15 ± 138.53 |

| Formlabs Biomed 80A | 14,747.70 ± 413.98 | 18,902.47 ± 60.54 | 5464.35 ± 357.03 | 747.86 ± 48.31 | |

| PS | 2542.78 ± 78.44 | 2439.99 ± 32.09 | 3172.09 ± 3712.09 | 383.69 ± 383.69 |

| IL-6 | IL-33 | IL-8 | MCP-1 | IL-23 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytotoxicity on extracts (dilution—10:0) | Formlabs Biomed 50A_ 1EO 24 h | 268.70 ± 45.63 | 53.82 ± 12.18 | 1041.84 ± 94.64 | 798.73 ± 11.31 | 264.02 ± NN |

| Formlabs Biomed 80A_1EO 24 h | 100.14 ± 21.69 | 33.75 ± 0.00 | 389.89 ± 550.96 | 530.19 ± 374.90 | 73.84 ± NN | |

| Formlabs Biomed 50A_1EO 48 h | 327.37 ± 15.38 | below detection level | 901.75 ± 9.40 | 1729.21 ± 53.60 | 219.73 ± 62.65 | |

| Formlabs Biomed 80A_1EO 48 h | 375.43 ± 15.38 | <13.90 | 1085.99 ± 63.82 | 1750.87 ± 70.67 | 219.73 ± 62.65 | |

| Formlabs Biomed 50A_1A 24 h | 175.09 ± 6.51 | below detection level | 456.56 ± 9.14 | 762.19 ± 1.95 | 124.64 ± 71.83 | |

| Formlabs Biomed 80A_1A 24 h | 169.89 ± 4.91 | <13.90 | 646.86 ± 12.00 | 756.48 ± 18.225 | 73.84 ± 52.21 | |

| Formlabs Biomed 50A_1A 48 h | 228.00 ± 3.98 | below detection level | 638.48 ± 26.60 | 1364.05 ± 72.09 | 219.73 ± 62.65 | |

| Formlabs Biomed 80A_1A 48 h | 198.83 ± 6.85 | <13.90 | 963.32 ± 36.96 | 1287.7 ± 30.59 | 73.84 ± 52.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dyner, M.; Dyner, A.; Byrski, A.; Surmiak, M.; Kopernik, M.; Kasperkiewicz, K.; Kurtyka, P.; Szawiraacz, K.; Pietruszewska, K.; Zajac, Z.; et al. Biocompatibility of Materials Dedicated to Non-Traumatic Surgical Instruments Correlated to the Effect of Applied Force of Working Part on the Coronary Vessel. Materials 2025, 18, 5645. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245645

Dyner M, Dyner A, Byrski A, Surmiak M, Kopernik M, Kasperkiewicz K, Kurtyka P, Szawiraacz K, Pietruszewska K, Zajac Z, et al. Biocompatibility of Materials Dedicated to Non-Traumatic Surgical Instruments Correlated to the Effect of Applied Force of Working Part on the Coronary Vessel. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5645. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245645

Chicago/Turabian StyleDyner, Marcin, Aneta Dyner, Adam Byrski, Marcin Surmiak, Magdalena Kopernik, Katarzyna Kasperkiewicz, Przemyslaw Kurtyka, Karolina Szawiraacz, Kamila Pietruszewska, Zuzanna Zajac, and et al. 2025. "Biocompatibility of Materials Dedicated to Non-Traumatic Surgical Instruments Correlated to the Effect of Applied Force of Working Part on the Coronary Vessel" Materials 18, no. 24: 5645. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245645

APA StyleDyner, M., Dyner, A., Byrski, A., Surmiak, M., Kopernik, M., Kasperkiewicz, K., Kurtyka, P., Szawiraacz, K., Pietruszewska, K., Zajac, Z., Mucha, L., Lackner, J. M., Berer, M., Major, B., & Basiaga, M. (2025). Biocompatibility of Materials Dedicated to Non-Traumatic Surgical Instruments Correlated to the Effect of Applied Force of Working Part on the Coronary Vessel. Materials, 18(24), 5645. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245645