1. Introduction

Lightweight engineering structures are widely used in aerospace, automotive, and industrial applications, where undesired vibrations can lead to noise, fatigue, and performance loss. Traditional approaches for vibration control commonly rely on additional damping layers or isolation systems. While effective, these solutions often increase weight and cost, which is undesirable in weight-sensitive sectors such as transportation and aeronautics.

An alternative strategy is to modify the structural geometry by introducing perforations or periodic features that alter the dynamic response of the system. Perforated plates, in particular, have been extensively studied in acoustics and vibration research as a practical means to attenuate structural vibrations and reduce sound radiation. The introduction of holes can redistribute stiffness and mass, creating local changes in modal behavior and, in some cases, effective attenuation of vibrational energy [

1]. Early works demonstrated that perforations influence both stiffness and mobility of thin plates, highlighting the need for accurate modeling of their dynamic properties [

2]. More recent studies extended this analysis to partially perforated geometries, such as circular plates, confirming that perforations significantly affect natural frequencies and modal distributions [

3]. Within this framework, perforated and phononic plates have emerged as promising candidates for lightweight and cost-efficient vibration suppression solutions, since they exploit geometric discontinuities to induce scattering and interference effects that reduce vibration transmission.

Most of the literature on phononic and metamaterial plates assumes idealized infinite periodicity, where the structure is represented by a repeating unit cell subjected to Bloch–Floquet boundary conditions. These models provide valuable insights into wave dispersion and bandgap mechanisms but neglect the finite-size effects, boundary conditions, and modal coupling that dominate in practical engineering components. In real applications, structures such as panels, casings, or enclosures are inherently finite, and their vibrational response cannot be captured solely through periodic analyses.

Recent works have demonstrated that even in finite perforated plates, geometric discontinuities can lead to localized resonance and partial attenuation effects similar to those observed in infinite periodic media. However, these effects are highly dependent on the actual plate dimensions, boundary conditions, and hole distribution, motivating the need for explicit modeling and optimization of finite systems.

Periodic perforated plates and phononic crystals have been widely investigated for their ability to inhibit wave propagation in certain frequency ranges, known as bandgaps. These structures achieve vibration suppression by exploiting periodic cavities or inclusions that alter dispersion properties and induce destructive interference effects. For instance, Andreassen et al. demonstrated directional bending wave propagation in periodically perforated plates, showing how periodic voids can create both partial and full bandgaps with anisotropic wave behavior [

4]. Similarly, Tomita et al. analyzed elastic wave attenuation in metaplates with periodic hollow shapes, demonstrating experimentally that such geometries generate effective bandgaps for vibration suppression [

5]. Wang et al. investigated phononic crystals with cross-like holes, reporting that non-convex geometries enable the formation of large and tunable bandgaps at relatively low frequencies [

6].

Advanced geometric configurations have also been proposed to broaden attenuation zones. Huang et al. studied slabs with cross-like holes on oblique lattices and showed that multiple flexural-wave attenuation zones can be achieved, with good agreement between numerical and experimental results [

7]. Das et al. extended this approach to plates with periodic cavities of varying shapes (square, circular, and rectangular), confirming the sensitivity of bandgap formation to cavity geometry and validating their predictions through experimental testing [

8].

Other investigations have examined acoustic scattering and dynamic effects in perforated plates. Cavalieri et al. developed a numerical framework for acoustic scattering by finite perforated elastic plates, highlighting how elasticity and porosity jointly influence the scattered field and vibration–acoustic coupling [

9]. Carbajo et al. introduced a finite element model for perforated panel absorbers that accounts for viscothermal effects, enabling more accurate representation of acoustic losses in complex perforated configurations [

10]. Similarly, Smirnov and Lebedev analyzed free vibrations of perforated thin plates with multiple cut-outs, emphasizing how hole size, shape, and position affect modal properties and natural frequencies [

11].

Together, these studies establish that periodicity and geometric complexity play a central role in the attenuation of structural vibrations and acoustic scattering. However, most works focus on uniform or repeated perforation patterns in infinite or quasi-infinite domains, leaving limited flexibility to fine-tune the response in finite, bounded structures.

Recent research has therefore shifted toward expanding the attenuation capabilities of perforated plates by moving beyond uniform hole configurations. One promising approach is the use of multiple hole diameters within the same structure. Kim and Yoon proposed a perforated plate with multiple-sized holes separated by porous partitions, showing that such configurations can substantially extend the absorption bandwidth compared to conventional single-sized designs [

12]. Similarly, Gallerand et al. demonstrated that microperforated plates with multi-size perforations and optimized spatial distributions can provide enhanced damping over a broader frequency range, especially when perforations are located in regions of maximum modal displacement [

13]. These works confirm that combining perforations of different sizes allows multiple resonance mechanisms to coexist, thereby broadening the effective attenuation band.

Parallel to these advances, optimization techniques have been applied to perforated and composite plates to enhance vibration performance. Duan introduced a two-dimensional sampling optimization method for composite plates with multiple circular holes, maximizing their fundamental frequency under various boundary conditions [

14]. Complementing this, Mohammadi et al. reviewed micro-perforated panel structures, identifying perforation diameter, perforation ratio, panel thickness, and spatial distribution as the most influential design parameters [

15]. These studies highlight that precise control and optimization of geometric features are crucial for achieving wideband and efficient vibration attenuation.

Despite the significant progress made in understanding the dynamic behavior of perforated and phononic plates, most existing studies have focused on identical perforations or grouped subsets with uniform sizes. While effective in generating bandgaps, these designs limit flexibility and the ability to finely tune attenuation within specific frequency ranges. Although advanced optimization methods, such as topology optimization and sampling-based algorithms, have been applied, they typically target global parameters or hole arrangements without addressing the possibility of treating each perforation as an independent variable. To date, the optimization of each perforation diameter individually has not been systematically explored. This gap highlights the opportunity to achieve more precise tailoring of the vibrational response by leveraging hole-to-hole variability within a single, finite plate.

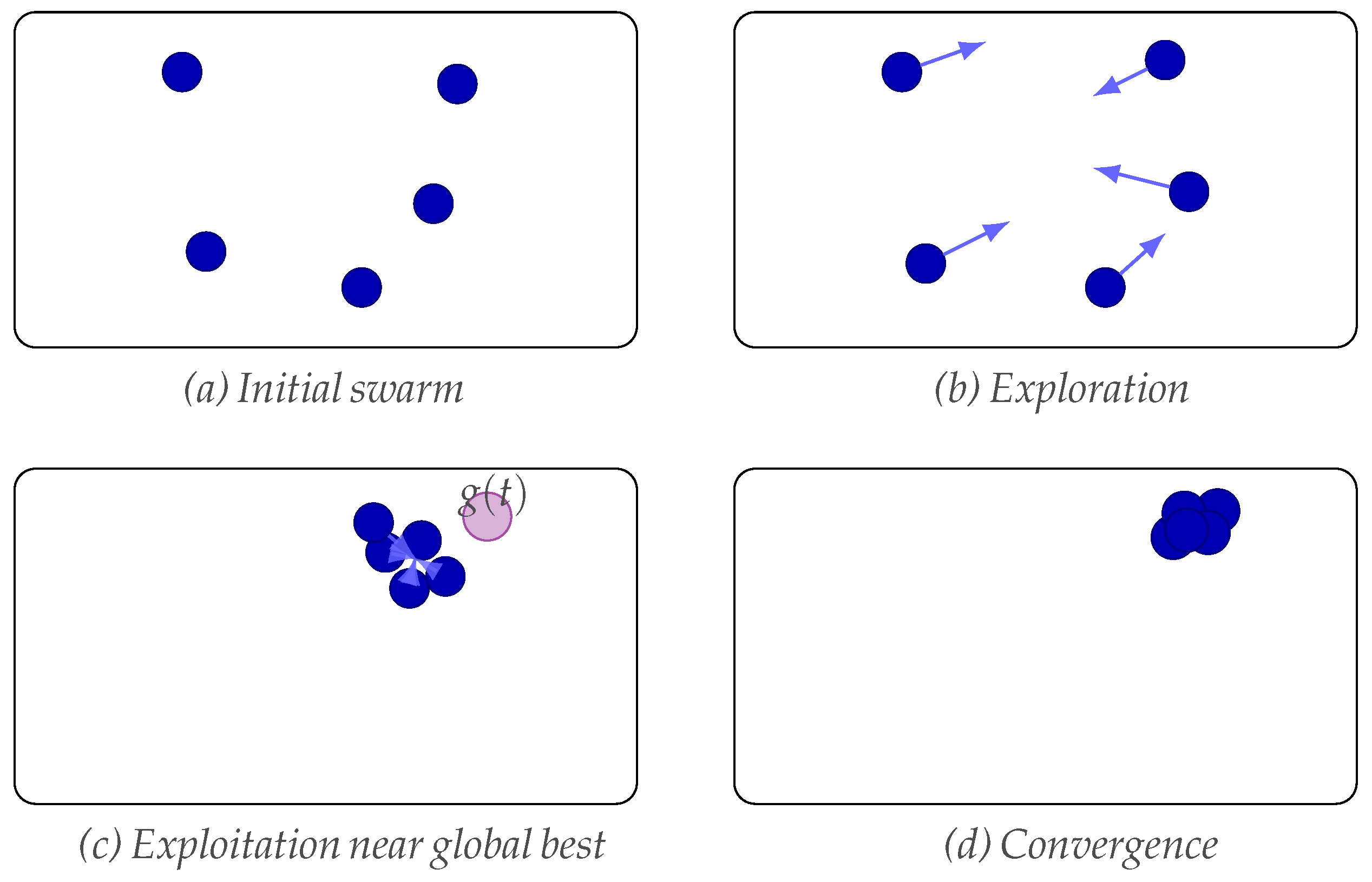

Optimizing perforated panels is inherently a nonlinear and multimodal problem, as changes in individual hole diameters simultaneously affect local stiffness, mass distribution, and modal coupling. Heuristic and population-based algorithms, such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), have emerged as powerful tools to address this class of problems due to their robustness, simplicity, and ability to escape local minima. Since its introduction by Kennedy and Eberhart [

16], PSO has gained broad adoption because of its conceptual simplicity, small number of control parameters, and suitability for parallel computation. The method balances exploration and exploitation through stochastic updates of particle velocities and positions, guided by both personal and global best solutions [

17,

18]. Over the years, several variants, such as inertia-weighted and constriction-factor PSO, have improved convergence stability and search efficiency [

19,

20]. Comparative studies have shown that PSO performs particularly well in continuous optimization problems with bounded design variables, including geometric parameter tuning in structural and acoustic applications [

21]. In the present work, PSO is employed to minimize the root-mean-square magnitude of the frequency response function (FRF) within prescribed frequency bands, enabling vibration suppression through direct geometric optimization without requiring gradient information.

The present study therefore introduces a novel methodology that combines finite element modeling (FEM) with Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to optimize the diameter of each perforation individually, targeting vibration suppression within predefined frequency ranges. This work focuses on the case of a finite perforated panels where modal behavior, boundary effects, and hole-to-hole interactions play a dominant role. The proposed numerical framework is validated experimentally through impact-hammer testing of aluminum panels fabricated via CNC machining. The results demonstrate that individualized perforation optimization can achieve vibration reductions of up to 90% in selected bands, clearly outperforming traditional uniform or periodic perforation designs. Beyond its scientific novelty, the proposed approach offers a lightweight, scalable, and cost-effective solution for vibration control, with promising applications in aerospace, automotive, and industrial systems where structural vibration mitigation is critical.

3. Case Study and Problem Statement

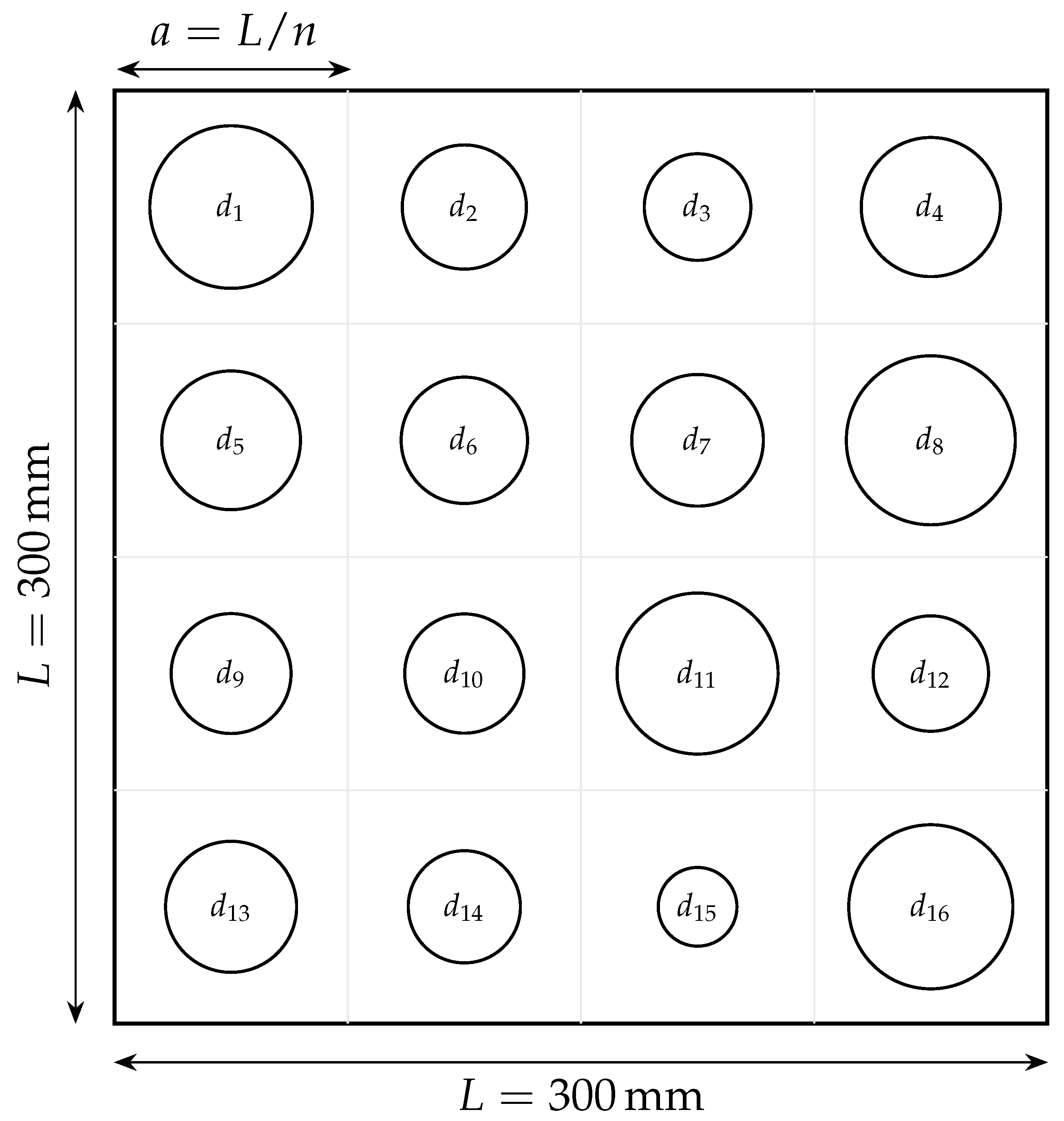

We consider a finite square aluminum plate of side

L = 300 mm and thickness

mm, perforated with either a

or a

grid of circular holes. The center-to-center grid pitch is

with the grid centered on the plate. As represented in

Figure 3, each circular hole is characterized by its diameter

, and the optimization treats the

diameters as independent design variables collected in

To ensure manufacturability and avoid overlap, box constraints and a minimum ligament are enforced:

together with a minimum ligament distance

between adjacent holes and between edge holes and the plate boundary. With hole centers on a square grid of pitch

a, choosing

is sufficient to satisfy both the no-overlap condition between neighbors and the edge-clearance requirement for border cells. Here we used

mm. The lower bound

can approach a small positive value (e.g.,

mm) to represent an effectively solid cell when desired.

The design goal is to minimize the global vibration level within an application-driven frequency band

. Let

denote the single-input/single-output FRF magnitude (accelerance) from a force DOF

k to response DOF

i. With

response locations, we define the location-averaged FRF magnitude as

and the band-wise root-mean-square (RMS) metric

where

is the number of sampled frequencies in the band. The optimization problem is

with

chosen such that

[see Equation (

10)]. This objective reduces the average FRF magnitude over the entire target band, yielding frequency-selective attenuation that is robust to narrow spectral features in finite plates.

The optimization focuses exclusively on vibration mitigation, without considering static or structural performance criteria. In particular, effects related to stress concentration, yielding, fatigue, or overall stability were not included in the optimization objective or constraints. All plates were modeled as linearly elastic thin structures undergoing small-amplitude vibrations, with the goal of minimizing dynamic response rather than ensuring load-carrying capacity. The free–free boundary conditions were adopted both numerically and experimentally, to replicate the suspension setup used in the roving-hammer tests. The excitation consisted of transient point forces normal to the plate surface, representing the hammer impacts applied during the experiments. Consequently, the optimization adjusted the hole diameters solely to minimize the vibration level within the target frequency bands, under the same material, geometry, and boundary conditions.

Problem (

13) is solved with a Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) scheme, using a swarm of

particles and a maximum of

iterations with early stopping on convergence. Particle positions are initialized uniformly within

for all

j. The inertia weight and acceleration coefficients followed conventional settings (

,

), which ensured stable convergence and consistent results across independent runs. The cost function

was evaluated for each particle based on the finite-element frequency response within the prescribed band

. It should be noted that

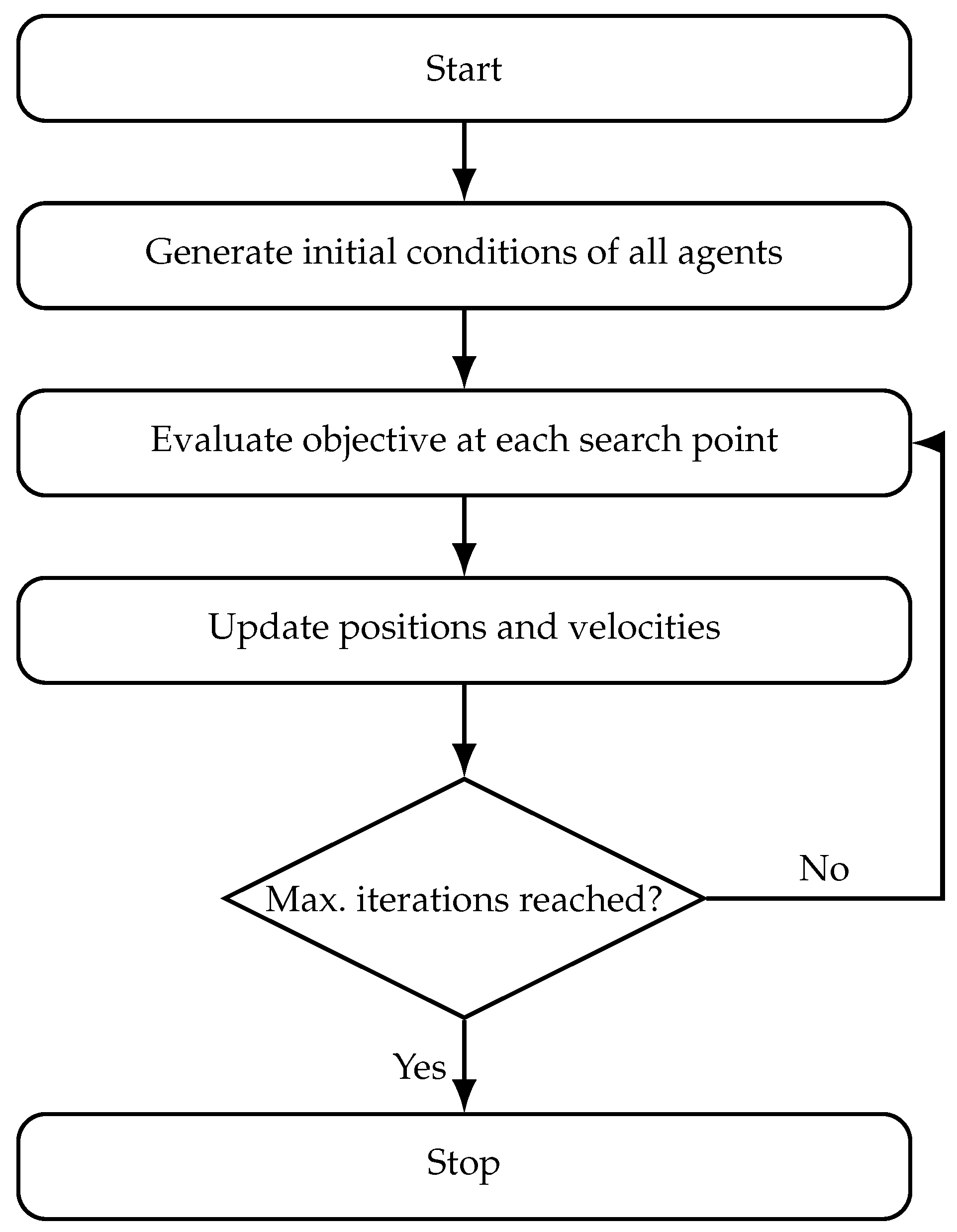

Figure 1 illustrates the generic workflow of the PSO algorithm, independent of the particular optimization problem. In the present study, the step labeled “Evaluate objective at each search point” corresponds specifically to computing the root-mean-square magnitude of the averaged frequency response function (FRF) within the target frequency band, as defined in Equations (

11) and (

12).

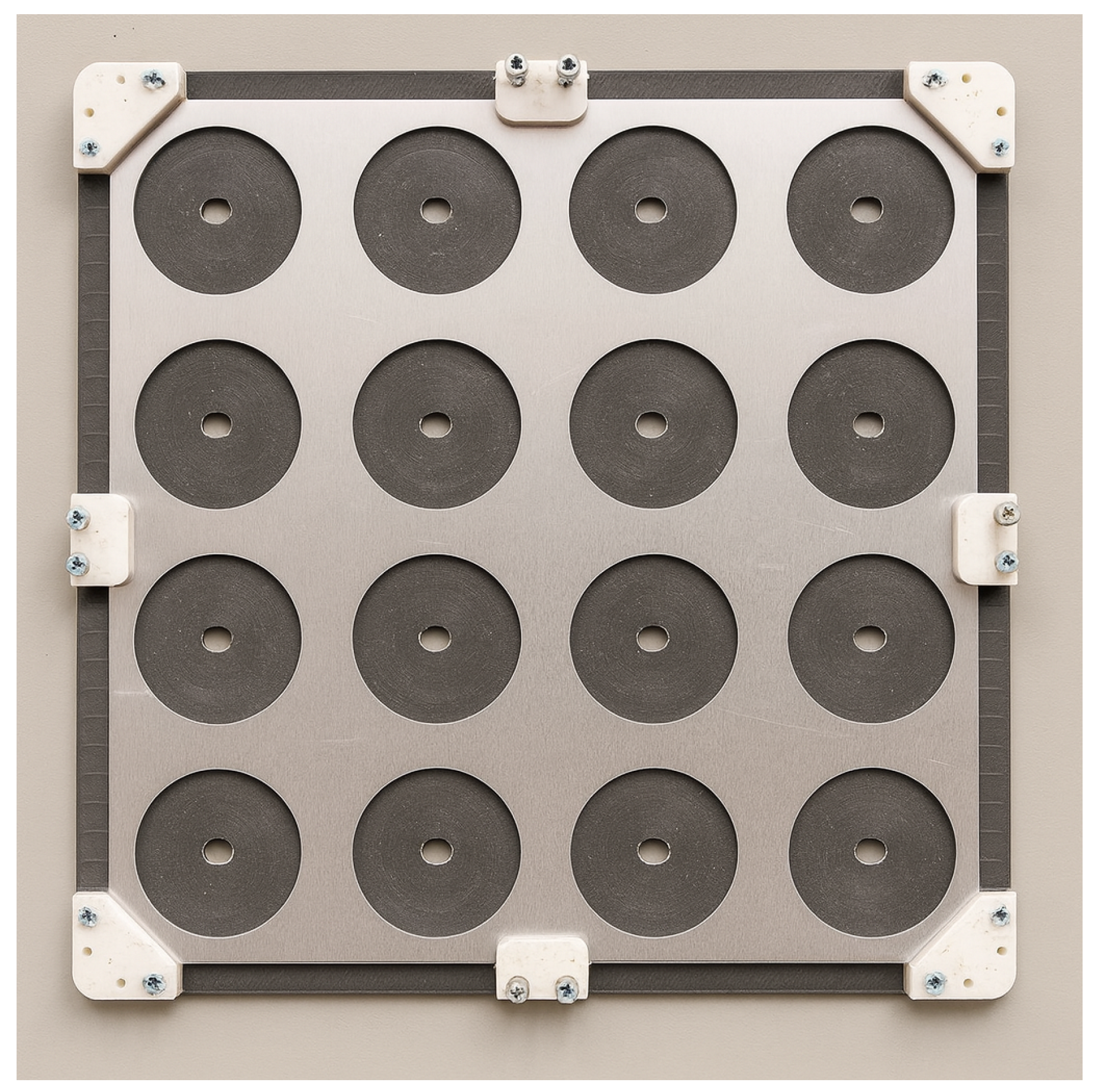

To isolate the benefit of individually tuned diameters, two uniform reference plates are used: a

panel with

mm in all cells and a

panel with

mm in all cells (

Figure 4).

4. Numerical Model

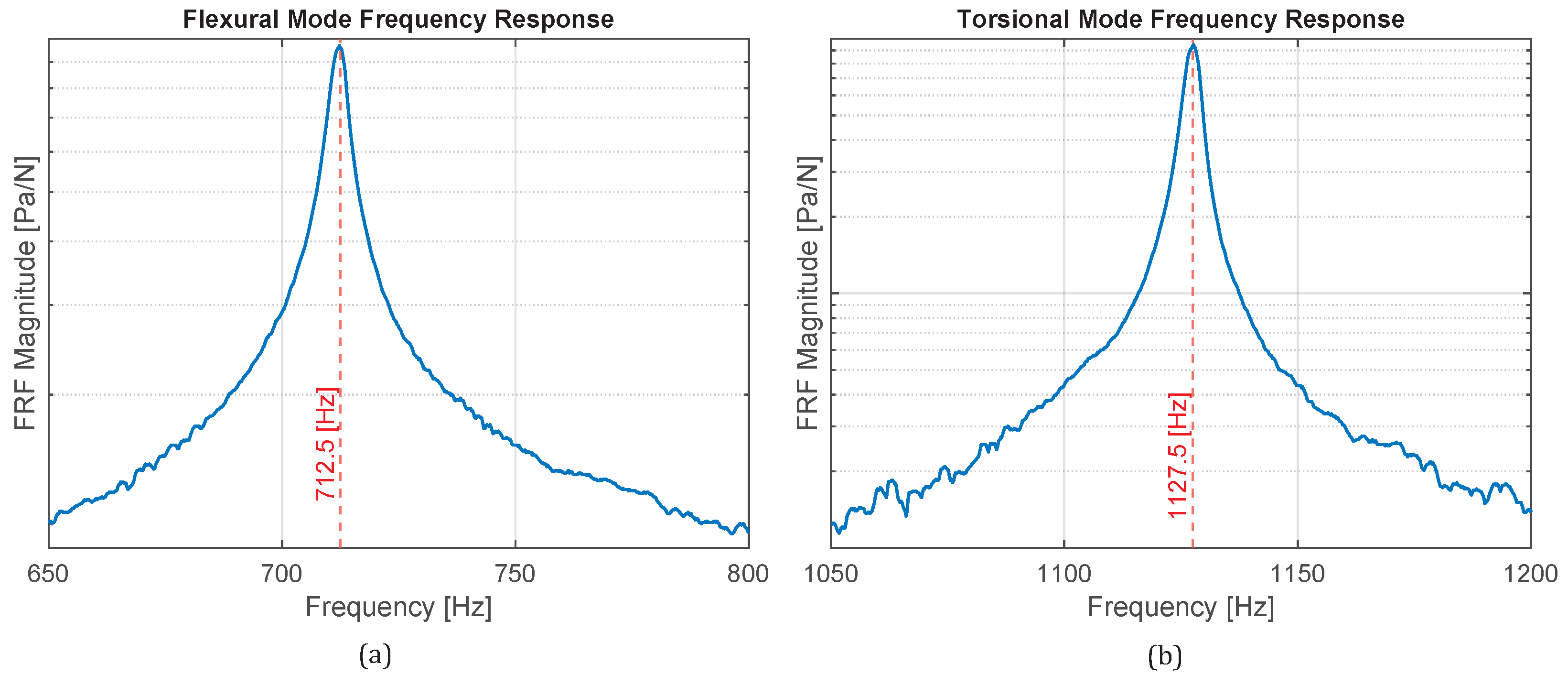

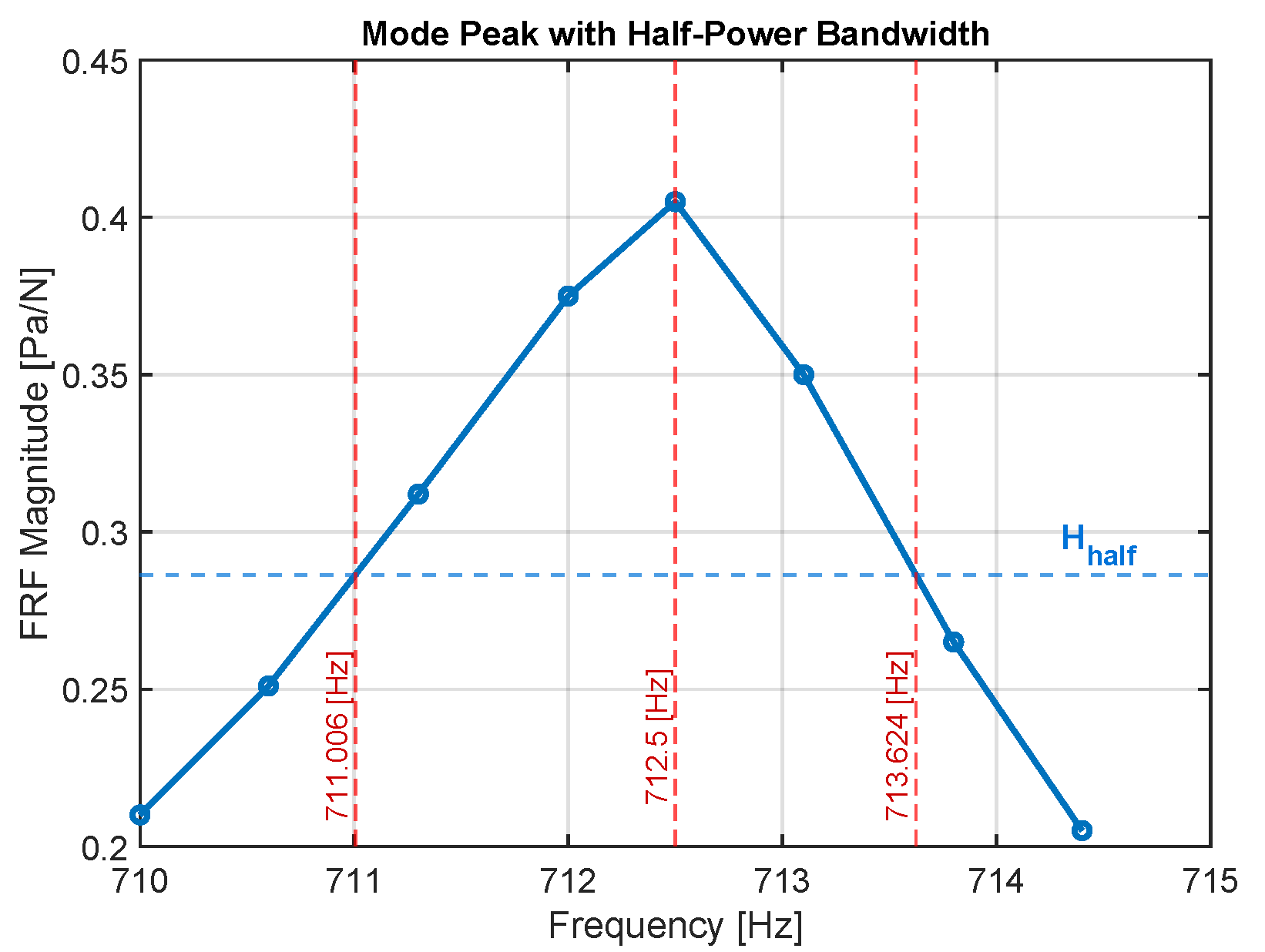

We modeled the square plate of side length mm and thickness mm in SDTools 6.2 2019 for MATLAB R2018b, using the built-in p_shell formulation. This element implements a Reissner–Mindlin (first-order shear deformation) plate/shell model, which includes transverse-shear effects and is suitable for thin to moderately thick plates.

The aluminum plate was modeled as a homogeneous, isotropic, and linearly elastic material with constant mechanical properties over the analyzed frequency range. The constitutive behavior follows the standard small-strain linear elastic model, characterized by an experimentally measured Young’s modulus

GPa and a Poisson’s ratio

. A uniform modal damping ratio of

was applied to all modes, with a mass density of

kg/m

3. Further details on the experimental characterization of these parameters are provided in

Section 5 and

Section 6.

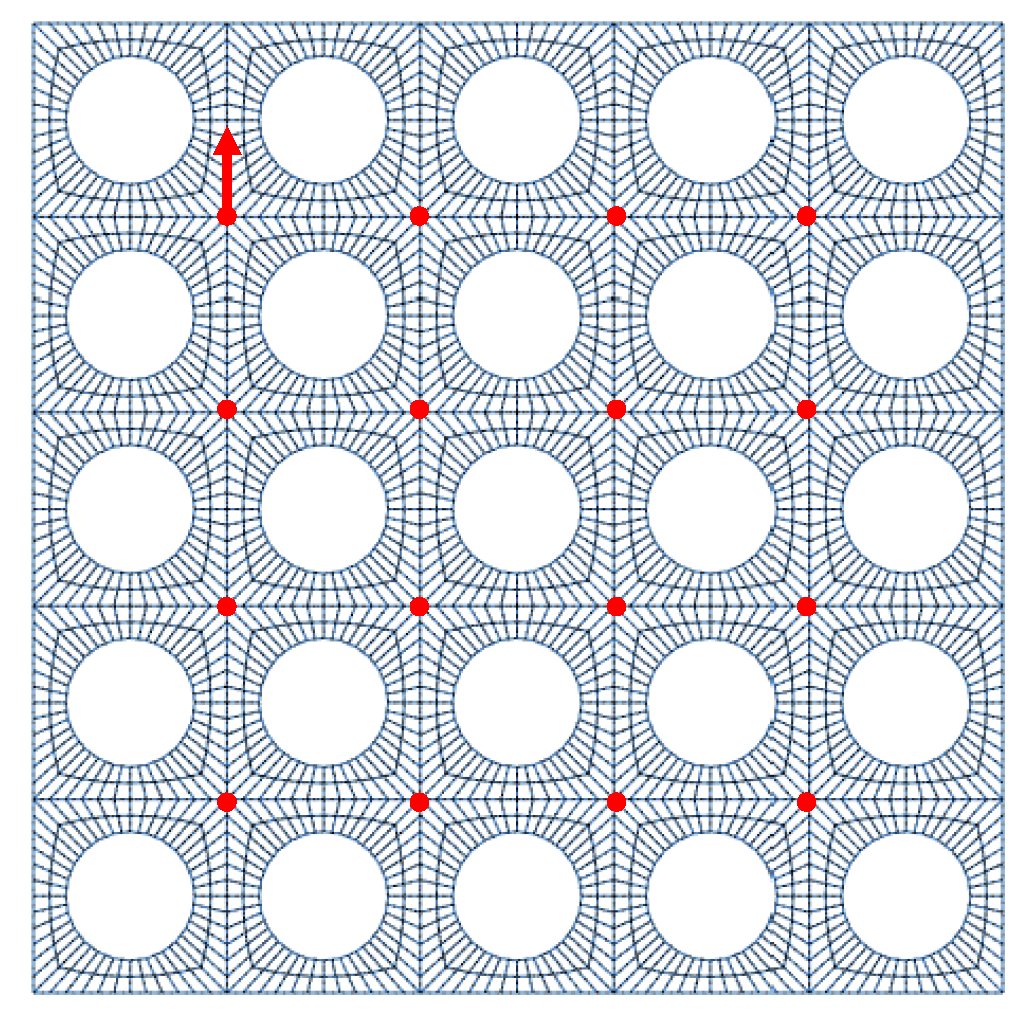

The perforations were represented explicitly in the finite-element mesh, and each unit cell contains a single circular cut-out whose diameter is treated as an independent design variable for the optimization. The finite-element assembly, boundary conditions, selection of excitation and response degrees of freedom, and the computation of frequency response functions (FRFs) were all implemented in MATLAB using the SDTools routines.

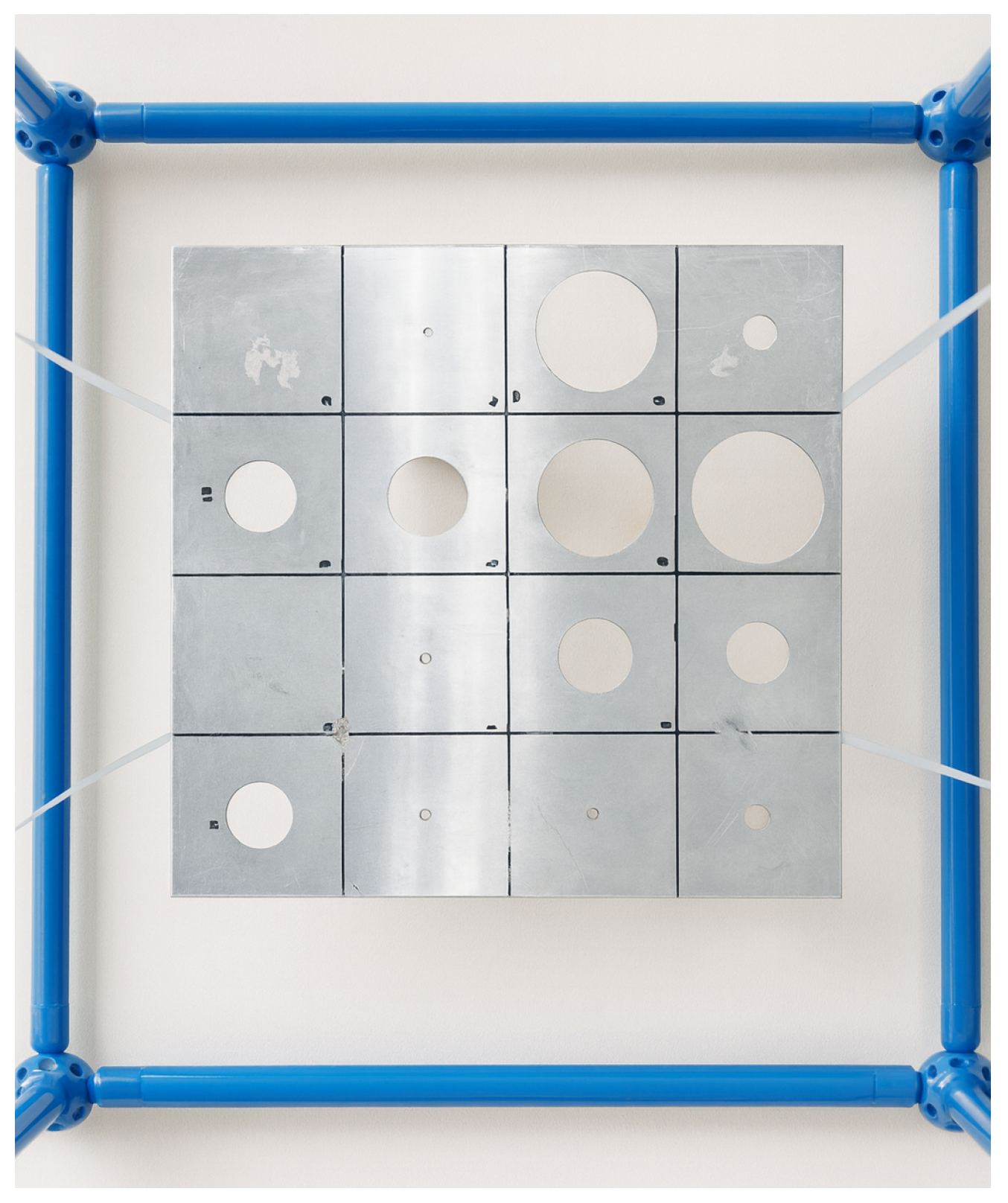

The finite-element model reproduced the configuration shown in

Figure 5, incorporating the fixed reference sensor location and the corresponding excitation points. This setup was used to compute a consistent set of frequency response functions (FRFs) with common reference and excitation positions, ensuring that the results remain independent of the perforation diameters and comparable across the different geometrical configurations considered during the optimization process.

For a given excitation degree of freedom k (impact point) and response degree of freedom i (accelerometer location), the single-input/single-output FRF is evaluated over the target frequency bands. To obtain a robust scalar measure per plate for the optimization objective, the magnitude of the FRFs from all response locations is averaged before computing the root-mean-square (RMS) value in each target frequency band. The FEM outputs were coupled with the PSO optimization loop to evaluate the RMS FRF amplitude over the prescribed frequency bands.

To verify the numerical convergence of the model, a mesh refinement analysis was conducted for the

perforated reference plate. Three meshes were generated with increasing local refinement. Representative wireframe views of the three meshes are shown in

Figure 6.

The averaged frequency response functions (FRFs) obtained from the coarse, medium, and fine meshes are compared in

Figure 7. All three meshes lead to practically identical results in the low-frequency range, including the first resonance modes, indicating that the global dynamic behavior is already well captured with the coarser discretization. Small differences appear only at higher frequencies (above approximately 800–900 Hz), where the finer geometric resolution slightly improves the accuracy of the local deformation fields around the perforation edges. However, the medium and fine meshes yield nearly indistinguishable FRFs over the full frequency range, with differences below 2%. For this reason, the medium mesh was adopted in all subsequent simulations, as it provides mesh-independent results while maintaining a reasonable computational cost.

Although the numerical model assumes nominally free–free boundary conditions, in the experiment the plate is suspended using elastic supports. To assess the influence of this practical boundary condition, elastic springs were added at four corner locations in the numerical model, connecting the out-of-plane displacement DOF to ground. Four stiffness levels were examined (

, 100, and 1000 N/m), where

represents a fully free condition (no spring) and the other values span the range of soft textile or rubber bands typically used in suspended setups. The resulting averaged FRFs (

Figure 8) show that the spring stiffness mainly affects the low-frequency range corresponding to rigid-body motions, shifting the first resonance by up to 1–8 Hz. However, for frequencies above 50 Hz, the effect of the boundary elasticity becomes negligible, and the FRF curves collapse for all tested stiffness values. Therefore, the free–free model provides an adequate representation for the frequency ranges analyzed in this study, and no boundary compliance correction is needed in the optimization phase.

7. Discussion

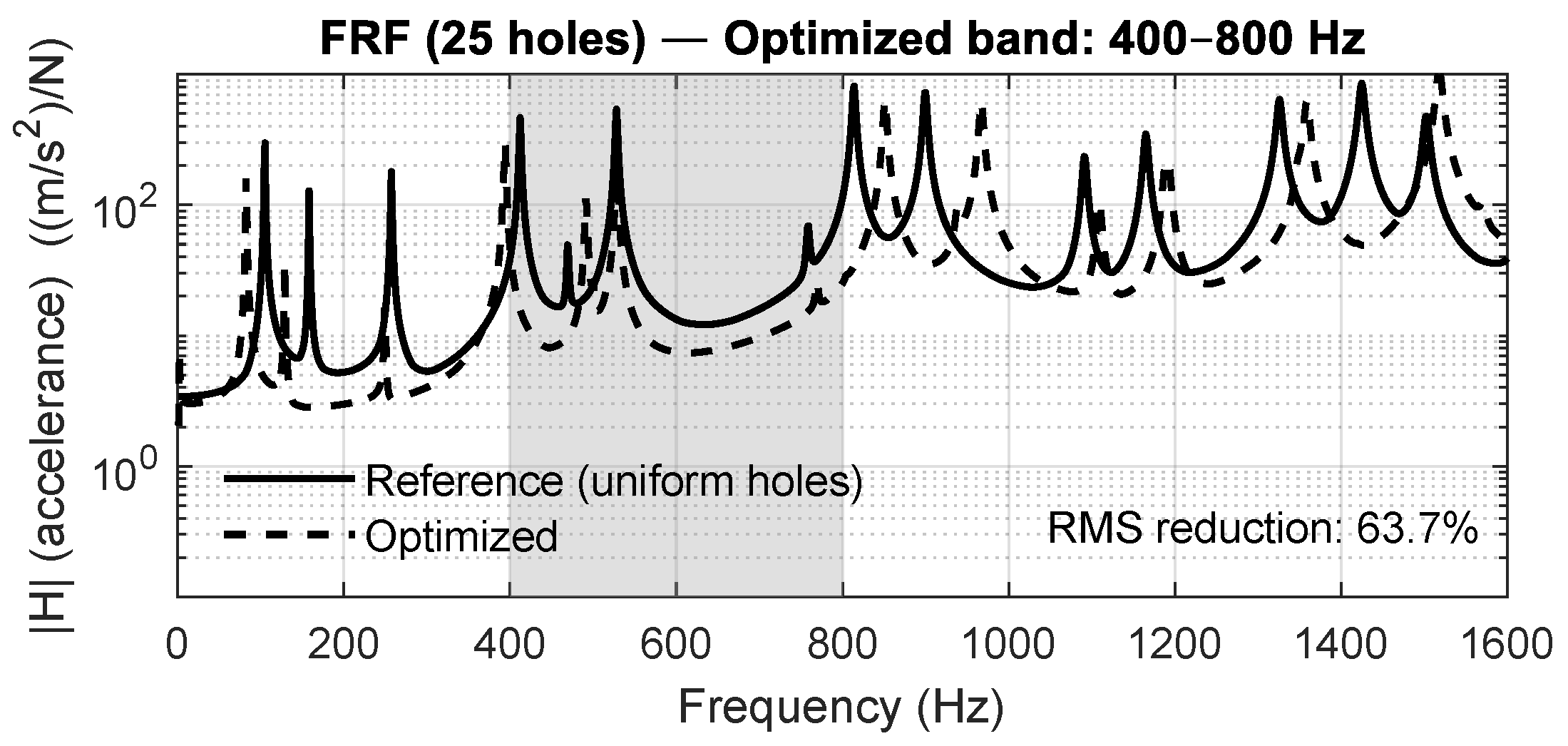

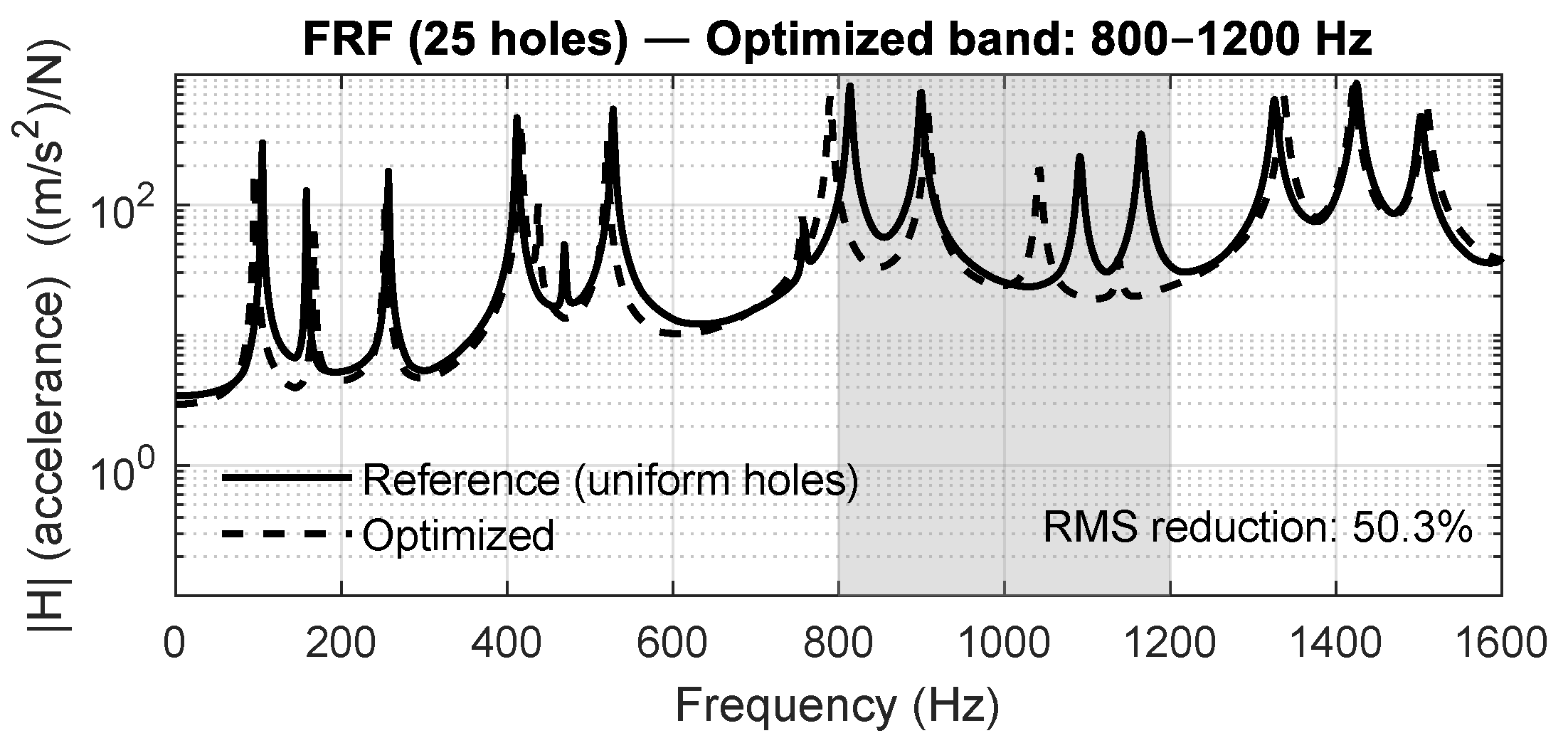

The results demonstrate that optimizing each perforation individually provides an effective and flexible means to achieve frequency-selective vibration attenuation in lightweight plates. Compared with traditional designs based on uniform or periodic perforations, the proposed approach allows fine tuning of the dynamic response, leading to a significant reduction in vibration amplitudes within prescribed bands while maintaining the same overall mass and geometry. The experimental validation confirmed these findings, with RMS reductions between 51% and 95% depending on the configuration and frequency range. From a physical perspective, the individually optimized layouts generate a spatially heterogeneous stiffness field that modifies the coupling between neighboring regions of the plate. This nonuniform stiffness distribution produces local impedance contrasts and partial wave reflections, mechanisms that can suppress bending wave propagation and concentrate modal energy away from the target frequency bands. Unlike periodic phononic structures, where bandgaps emerge due to translational symmetry and Bragg scattering, the present approach achieves similar attenuation through an aperiodic yet physically consistent configuration of perforations. This result suggests that precise control of local compliance, rather than strict periodicity, is sufficient to induce localized vibration suppression in thin plates.

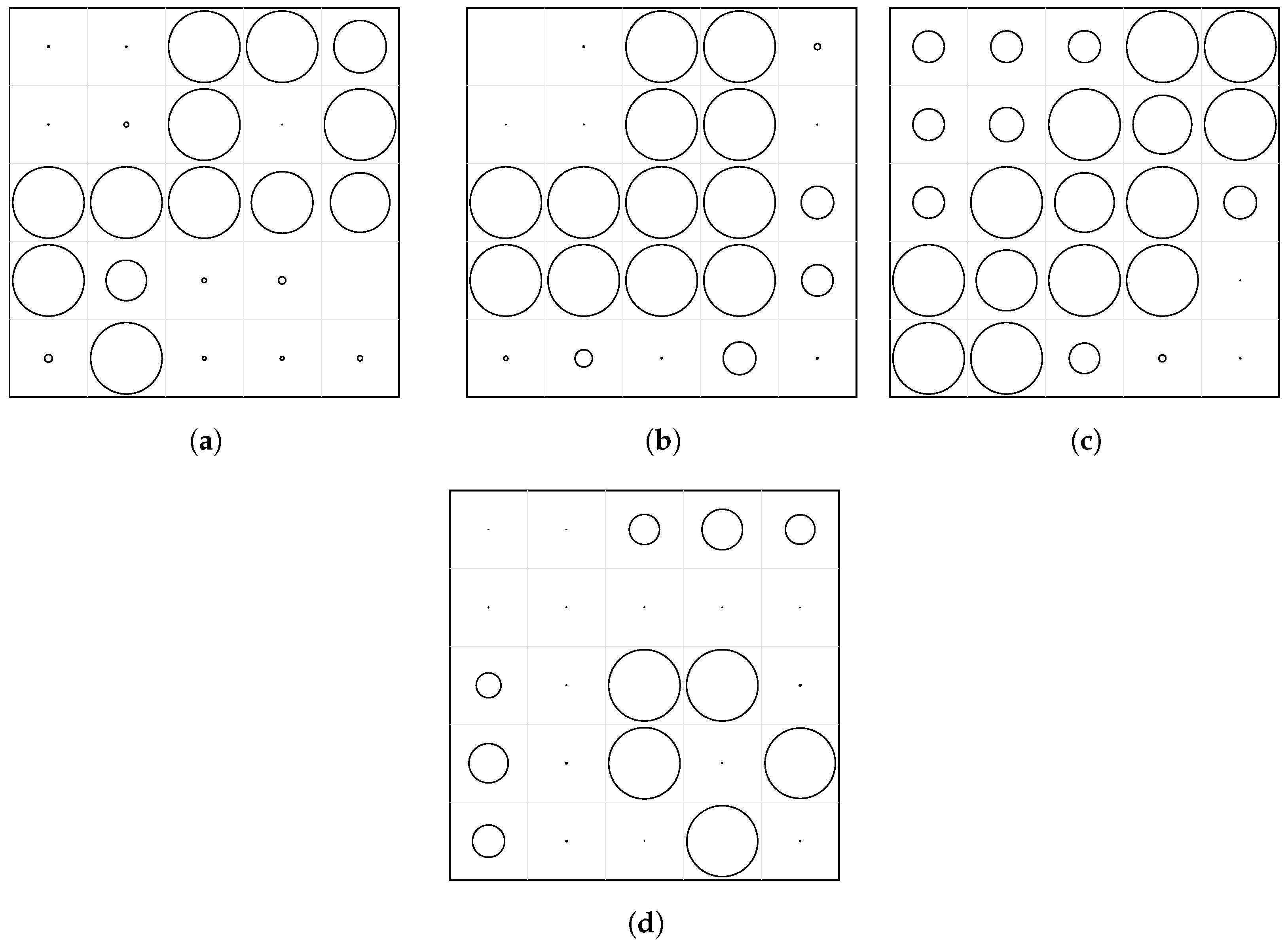

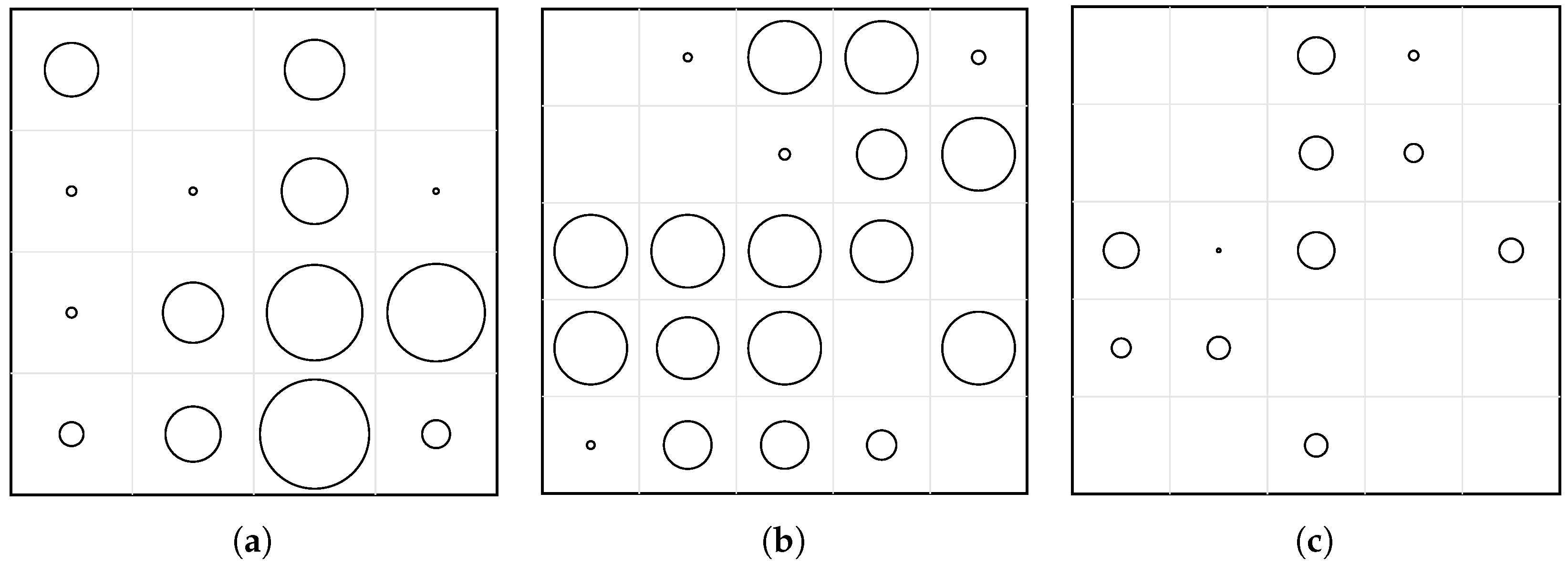

The optimized perforation layouts (

Figure 20) exhibit characteristic spatial patterns that depend on the target frequency band. In the low-frequency case (200–400 Hz, Case A), the algorithm favored larger perforations clustered toward one corner of the plate, with smaller holes or solid regions along the opposite diagonal. This asymmetry increases local flexibility in regions of high modal curvature, effectively shifting the first bending modes to higher frequencies. In the mid- and high-frequency cases (600–800 Hz and 500–1000 Hz, Cases B and C), the optimized patterns become more evenly distributed and show partial symmetry with respect to the plate diagonal. This quasi-symmetric arrangement results in a more balanced stiffness field, reducing modal coupling and ensuring attenuation across several higher-order modes.

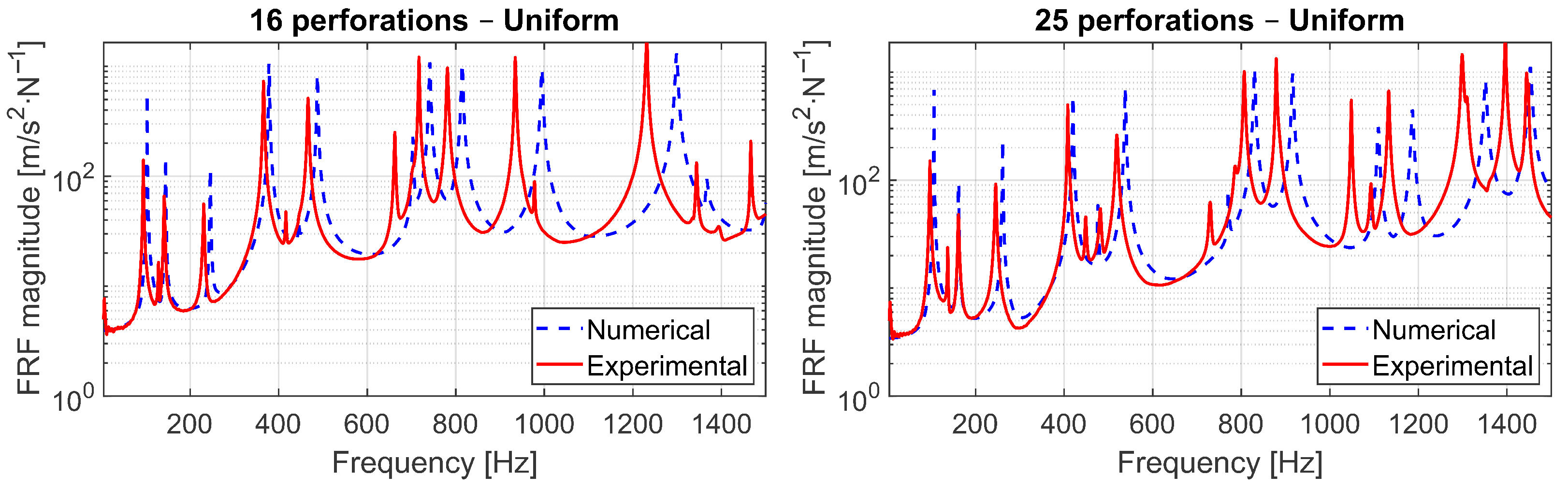

When comparing the numerical and experimental FRFs, an excellent correspondence is observed in the low–frequency range, confirming the predictive capability of the finite-element model and the adequacy of the identified damping ratio. At higher frequencies, small differences appear in the spacing and amplitude of resonant peaks (

Figure 22). The mesh refinement analysis demonstrated that these discrepancies are not associated with discretization, since the medium and fine meshes yield virtually identical FRFs. Likewise, the boundary compliance study showed that the suspended support condition only affects the rigid-body region below 50 Hz, with negligible influence in the frequency bands of interest. Therefore, the remaining deviations can be primarily attributed to (i) uncertainties in the material properties of the manufactured plate and (ii) the idealizations inherent to the plate formulation (e.g., Reissner–Mindlin kinematics, constant thickness, and perfectly circular perforations). Minor geometric tolerances introduced during machining and small mass loading effects from the accelerometer may further contribute to the observed differences. Despite these factors, the agreement remains strong across the operational frequency bands relevant to the optimization.

The results also indicate that the observed vibration reduction is primarily associated with changes in stiffness distribution rather than simple mass effects. In fact, the optimized plates exhibit a slightly higher total mass than the uniform reference plates, since the optimization process tends to enlarge certain perforations while leaving others unperforated, leading to a net material increase. This finding confirms that the attenuation mechanism is fundamentally structural-dynamic—driven by controlled stiffness gradients and modal interference rather than a consequence of mass reduction.

The present work focused exclusively on vibration mitigation through geometric optimization of perforation diameters under fixed free–free boundary conditions. Nevertheless, the proposed methodology can be readily extended to include additional geometric and boundary parameters, such as plate thickness, hole arrangement, or support conditions, enabling a more comprehensive parametric exploration of their influence on dynamic behavior. Furthermore, future studies could couple the present vibration-based objective with structural criteria such as stress concentration, stiffness retention, or fatigue life, thereby establishing a multi-objective optimization framework that balances vibration suppression and mechanical strength. Such an extension would allow assessing how the perforation pattern affects both the dynamic response—quantified by the root-mean-square amplitude of the frequency response function—and the static performance of the plate.

8. Conclusions

This work presented a combined numerical–experimental framework for the design and validation of finite perforated cellular panels for vibration mitigation. Unlike most previous studies, which focus on infinitely periodic or idealized unit-cell models, the proposed approach considers finite plates and individually optimizes the diameter of each perforation, enabling precise control of the structural dynamic response within specific frequency bands.

Finite element models were integrated with a Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm to minimize the root-mean-square amplitude of the frequency response function (FRF) in predefined frequency ranges. The optimized aluminum panels were subsequently fabricated and experimentally tested, showing strong agreement with numerical predictions. Reductions of up to 90% in vibrational amplitude were achieved within the targeted bands, confirming the effectiveness of the optimization strategy and validating the predictive capability of the numerical model.

The results demonstrate that individualized perforation optimization provides a lightweight, efficient, and scalable solution for vibration suppression, outperforming conventional uniform designs. By tailoring the stiffness and mass distribution through local geometric tuning, it is possible to achieve selective attenuation without adding external damping materials or increasing structural mass. While this study focused on aluminum plates with circular perforations and free–free boundary conditions, the methodology can be readily extended to other materials, non-circular geometries, and different boundary configurations.

Overall, the proposed framework establishes a practical and computationally efficient route for the design of advanced perforated panels with frequency-selective vibration control.