A Cross-Scale Spatial–Semantic Feature Aggregation Network for Strip Steel Surface Defect Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We design a novel CSSFAN that adopts a bottom-up pyramid-aware feature aggregation strategy combined with CSSAMs, enhancing the spatial representation of high-level features while maintaining semantic consistency.

- We develop an ARPN that dynamically adjusts the number and spatial density of proposals according to local feature complexity, addressing the uneven spatial distribution of defects.

- Extensive experiments conducted on two benchmark datasets for strip steel surface defect detection demonstrate that the proposed method consistently outperforms state-of-the-art approaches in terms of detection accuracy and robustness.

2. Related Work

2.1. Strip Steel Surface Defect Detection

2.2. Multiscale Feature Fusion

3. Method

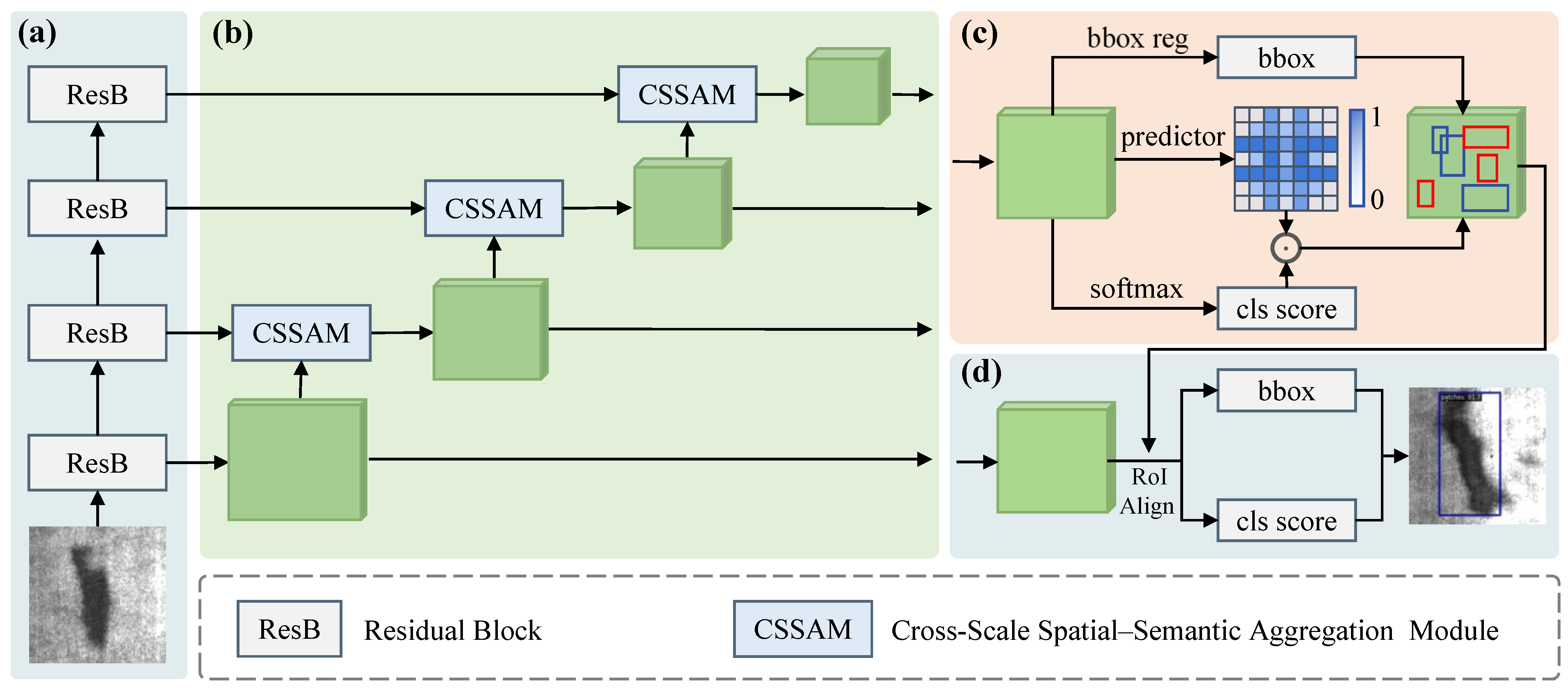

3.1. Overall

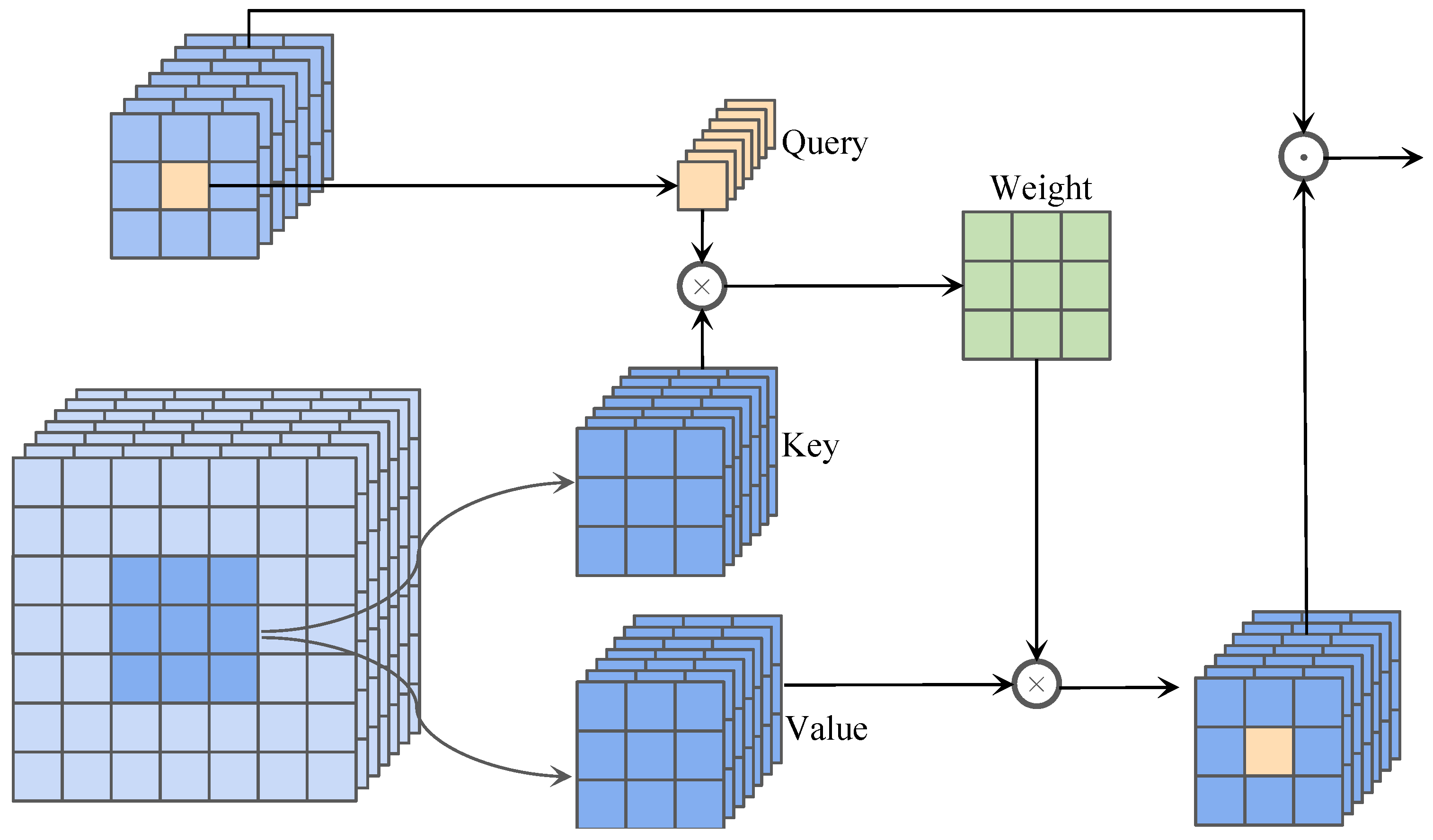

3.2. Cross-Scale Spatial–Semantic Aggregation Modules (CSSAM)

3.2.1. Query Construction and Key-Value Extraction

3.2.2. Cross-Attention Computation

3.2.3. Feature Reconstruction and Fusion

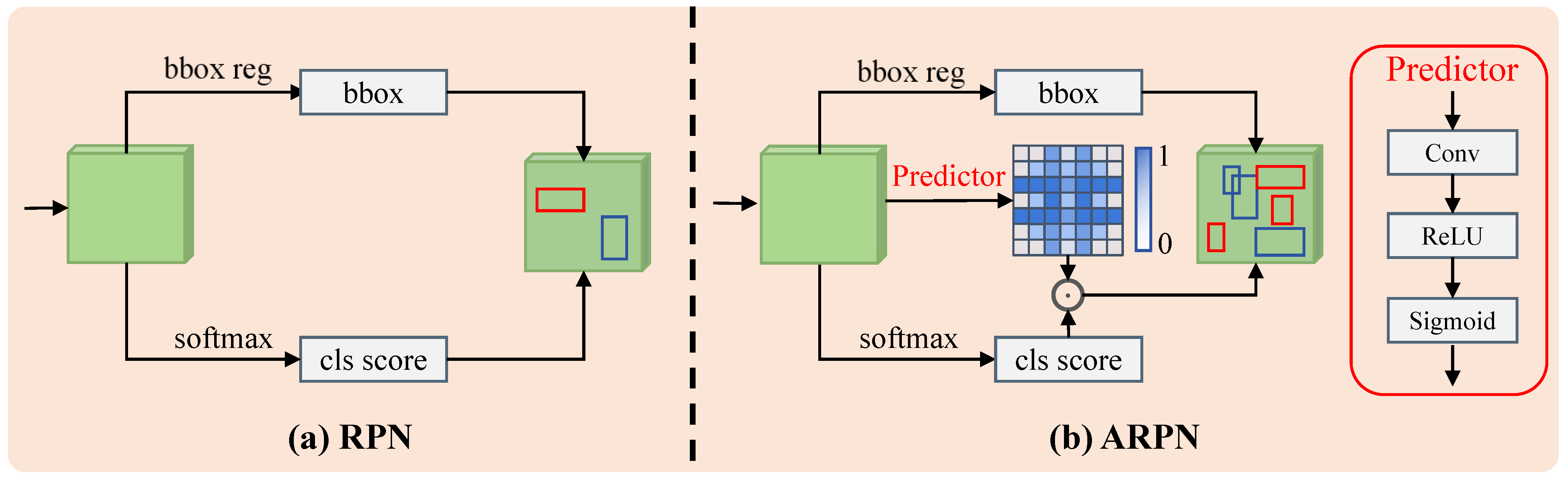

3.3. Adaptive Region Proposal Network (ARPN)

3.3.1. Density Score Estimation

3.3.2. Adaptive Anchor Reweighting

3.4. Loss Function

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Implementation Details

4.1.2. Datasets

4.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

4.2. Quantitative Comparison

4.2.1. Quantitative Comparison on NEU-DET Dataset

4.2.2. Quantitative Comparison on GC10-DET Dataset

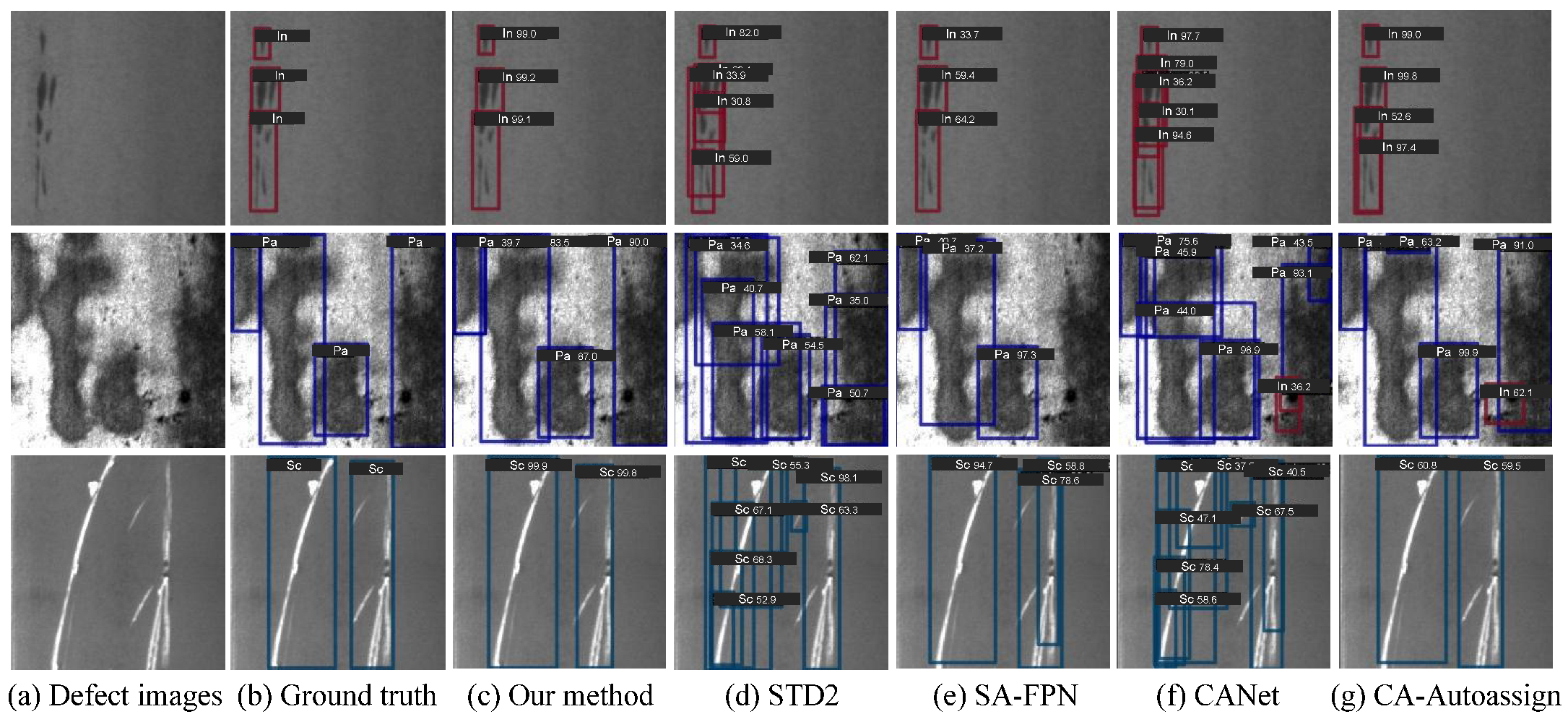

4.3. Visual Comparison

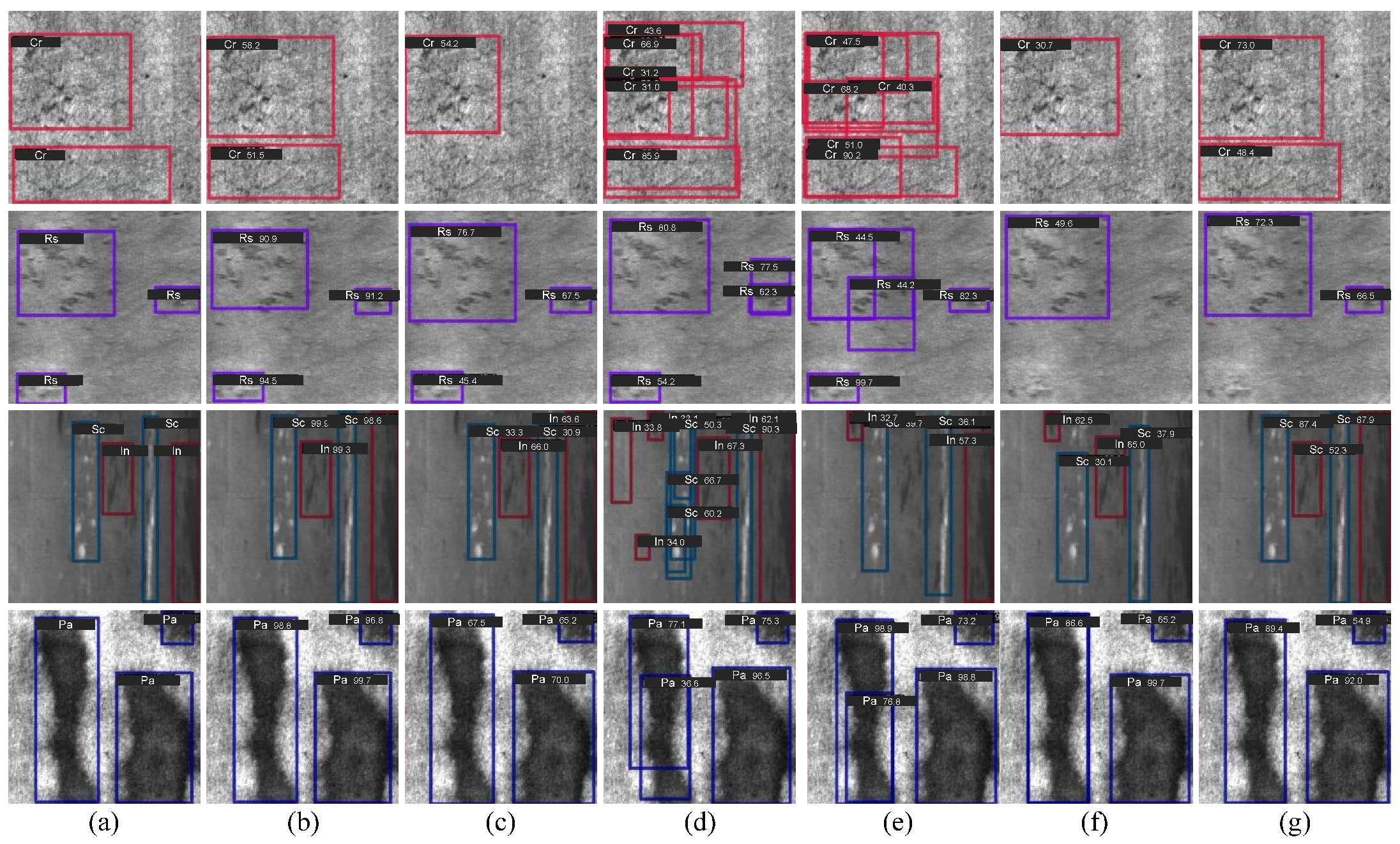

4.3.1. Visual Comparison on NEU-DET

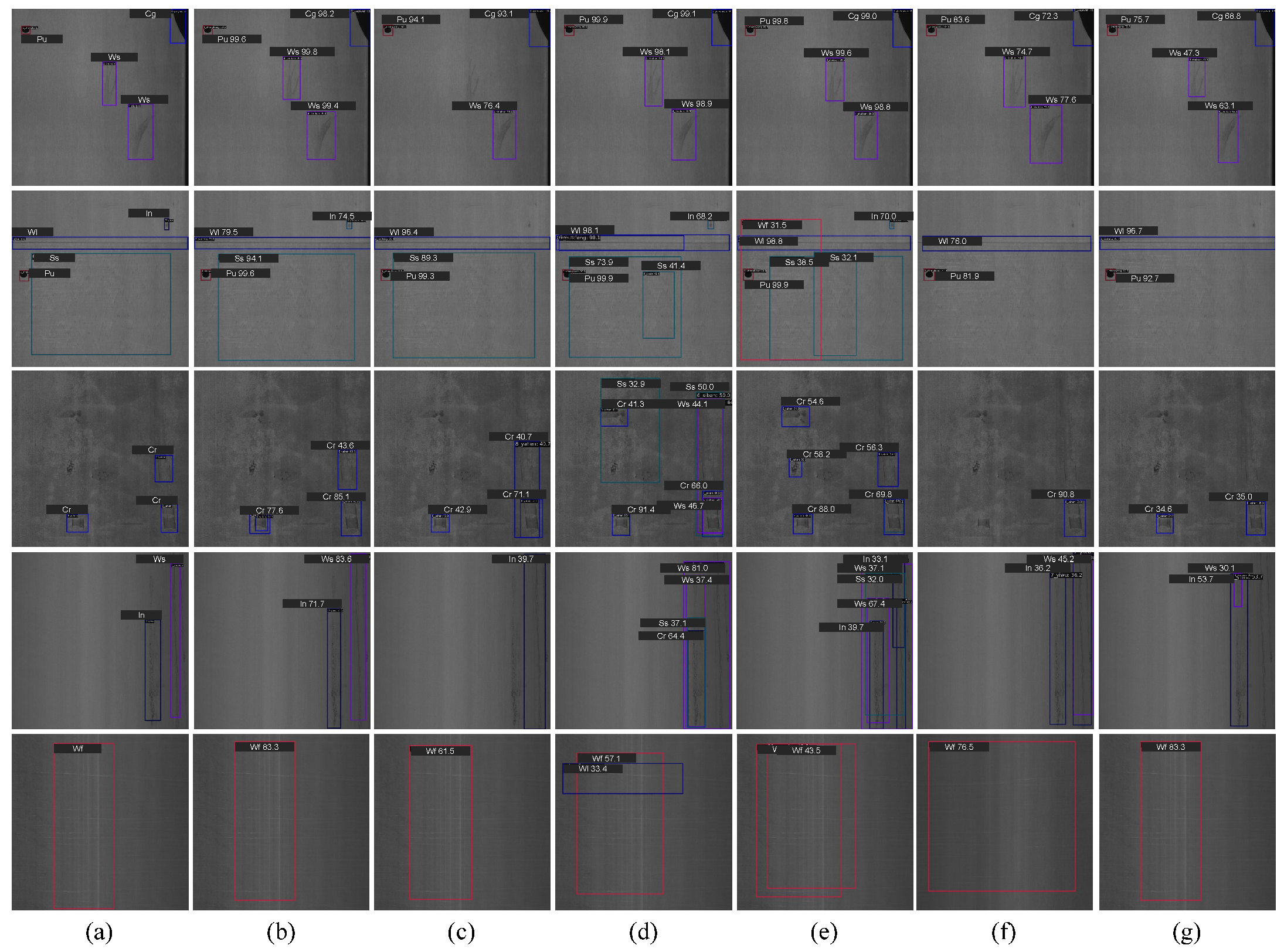

4.3.2. Visual Comparison on GC10-DET

4.4. Ablation Experiments

4.5. Effectiveness of CSSFAN

4.6. Generalization Experiments

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, H.; Hu, R.; Dong, H.; Liu, Z. SFC-YOLOv8: Enhanced Strip Steel Surface Defect Detection Using Spatial-Frequency Domain-Optimized YOLOv8. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 9700111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wei, X.; Hassaballah, M.; Li, Y.; Jiang, X. A deep learning model for steel surface defect detection. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, W.; Zhang, B.; Gu, Z. YOLOv8n-GSE: Efficient Steel Surface Defect Detection Method. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 166343–166356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Zhang, J.; Mu, D. Steel Defect Detection Based on YOLO-SAFD. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 77291–77304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, C.C.; Lam, K.M. Efficient fused-attention model for steel surface defect detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 2510011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Gao, L.; Wang, Y.; Deng, Z.; Tao, Y. EC-YOLO: Effectual Detection Model for Steel Strip Surface Defects Based on YOLO-V5. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 62765–62778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xu, A.; Zhang, Q.; Cai, Y. Steel Surface Defect Detection Method Based on Improved YOLOX. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 37643–37652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Wang, Z.Z.; Liu, X.L.; Zhang, P.; Tian, Z.W.; Qian, R.L. SDD-Net: A Steel Surface Defect Detection Method Based on Contextual Enhancement and Multiscale Feature Fusion. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 185740–185756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Cao, S.; Zhang, J.; Hou, Z. Steel surface defect detection algorithm based on YOLOv8. Electronics 2024, 13, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Chen, L.; Sun, W.; Lin, Z.k. Review of surface defect detection of steel products based on machine vision. IET Image Process. 2023, 17, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, C.; Hu, R.; Bin, J.; Dong, H.; Liu, Z. CGTD-net: Channel-wise global transformer-based dual-branch network for industrial strip steel surface defect detection. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 4863–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Shan, J.; He, Y.; Song, K. Steel surface defect recognition: A survey. Coatings 2022, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Chu, M.; Zhang, L. A detection network for small defects of steel surface based on YOLOv7. Digit. Signal Process. 2024, 149, 104484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Yu, M.; Liu, J. Lightweight strip steel defect detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv7. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ding, Y.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, E.; Wu, Z.; Shao, L. Surface defect detection methods for industrial products: A review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Jia, M. DCC-CenterNet: A rapid detection method for steel surface defects. Measurement 2022, 187, 110211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, S.; Teymouri, S.; Etaati, S.; Khoramdel, J.; Borhani, Y.; Najafi, E. Steel surface defect detection and segmentation using deep neural networks. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Ning, H.; Tang, X.; Yang, Z. GDCP-YOLO: Enhancing steel surface defect detection using lightweight machine learning approach. Electronics 2024, 13, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.A.; Desai, K.A. Automated surface defect detection framework using machine vision and convolutional neural networks. J. Intell. Manuf. 2023, 34, 1995–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohag Mia, M.; Li, C. STD2: Swin Transformer-Based Defect Detector for Surface Anomaly Detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 3492728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 8759–8768. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Li, N.; Li, J.; Gao, B.; Niu, D. SA-FPN: Scale-aware attention-guided feature pyramid network for small object detection on surface defect detection of steel strips. Measurement 2025, 249, 117019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Liu, M.; Zhang, S.; Wei, P.; Chen, B. CANet: Contextual information and spatial attention based network for detecting small defects in manufacturing industry. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 140, 109558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Fang, M.; Qiu, Y.; Xu, W. An anchor-free defect detector for complex background based on pixelwise adaptive multiscale feature fusion. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 72, 5002312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Cui, Y.; Cui, Y.; Xu, R.; Yang, J.; Zhou, J. Optimization algorithm of steel surface defect detection based on YOLOv8n-SDEC. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 95106–95117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukup, D.; Huber-Mörk, R. Convolutional neural networks for steel surface defect detection from photometric stereo images. In Advances in Visual Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 668–677. [Google Scholar]

- Sophian, A.; Tian, G.Y.; Zairi, S. Pulsed magnetic flux leakage techniques for crack detection and characterisation. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2006, 125, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Barnard, K. Attentional local contrast networks for infrared small target detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 9813–9824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Ma, W.; Sun, X. An efficient re-parameterization feature pyramid network on YOLOv8 to the detection of steel surface defect. Neurocomputing 2025, 614, 128775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Chen, Y.; Jia, X.; Ma, T. Steel surface defect detection algorithm in complex background scenarios. Measurement 2024, 237, 115189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhou, S.; Tai, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, S.; Liu, J.; Xu, K.; Peng, T.; Zhang, Z. An improved faster R-CNN for steel surface defect detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 24th International Workshop on Multimedia Signal Processing (MMSP), Shanghai, China, 26–28 September 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A convnet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 11976–11986. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Du, Y.; Fu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zeng, H. DCAM-Net: A rapid detection network for strip steel surface defects based on deformable convolution and attention mechanism. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 5005312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Cai, Z. Steel surface defect detection based on improved YOLOv8. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Algorithms, High Performance Computing, and Artificial Intelligence (AHPCAI 2023), Yinchuan, China, 18–19 August 2023; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2023; Volume 12941, pp. 1356–1360. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Han, K.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y. GhostNetv2: Enhance cheap operation with long-range attention. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 9969–9982. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Chu, M.; Gong, R.; Zheng, Z. Global attention module and cascade fusion network for steel surface defect detection. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 158, 110979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi, G.; Lin, T.Y.; Le, Q.V. NAS-FPN: Learning scalable feature pyramid architecture for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 7036–7045. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10781–10790. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, A.; Mohri, M.; Zhong, Y. Cross-entropy loss functions: Theoretical analysis and applications. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 23803–23828. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Cao, Z.; Huang, T. Unitbox: An advanced object detection network. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 15–19 October 2016; pp. 516–520. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Wang, J.; Pang, J.; Cao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, S.; Feng, W.; Liu, Z.; Xu, J.; et al. MMDetection: Open MMLab Detection Toolbox and Benchmark. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.07155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Song, K.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Yu, H.; Li, X. Triplet-graph reasoning network for few-shot metal generic surface defect segmentation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 5011111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Yan, Y. A noise robust method based on completed local binary patterns for hot-rolled steel strip surface defects. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 285, 858–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Song, K.; Meng, Q.; Yan, Y. An end-to-end steel surface defect detection approach via fusing multiple hierarchical features. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2019, 69, 1493–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Duan, F.; Jiang, J.j.; Fu, X.; Gan, L. Deep metallic surface defect detection: The new benchmark and detection network. Sensors 2020, 20, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Proceedings, Part V 13. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Proceedings, Part I 14. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, C.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, Y.; Scott, M.R.; Huang, W. Tood: Task-aligned one-stage object detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 3490–3499. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Fu, Y. Rethinking classification and localization for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10186–10195. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z.; Vasconcelos, N. Cascade R-CNN: Delving into high quality object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 6154–6162. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Chang, H.; Ma, B.; Wang, N.; Chen, X. Dynamic R-CNN: Towards high quality object detection via dynamic training. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Proceedings, Part XV 16. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 260–275. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Li, B.; Yue, Y.; Li, Q.; Yan, J. Grid R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 7363–7372. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, J.; Chen, K.; Shi, J.; Feng, H.; Ouyang, W.; Lin, D. Libra r-cnn: Towards balanced learning for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 821–830. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, Y.; Kong, T.; Xu, C.; Zhan, W.; Tomizuka, M.; Li, L.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, C.; et al. SparseR-CNN: End-to-End Object Detection with Learnable Proposals. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.12450. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Liao, H.Y.M. Yolov9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.13616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14458. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. DETRs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Lei, J.; Zhu, Z.; Cheng, S.; Feng, Z.; Liang, R. AFPN: Asymptotic feature pyramid network for object detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Honolulu, HI, USA, 1–4 October 2023; pp. 2184–2189. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M.; Yang, B.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; He, Y. Fine coordinate attention for surface defect detection. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 123, 106368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hyperparameters | Learning Rate | Weight Decay | Momentum Coefficien | Optimizer | Batch Size | Train:Test | Epoch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 0.008 | 0.0001 | 0.9 | SGD | 2 | 8:2 | 36 |

| Methods | AP | AP50 | AP75 | APS | APM | APL | Cr | In | Pa | Ps | Rs | Sc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSD300 [50] | 39.7 | 73.7 | 34.4 | 33.8 | 33.3 | 51.2 | 48.8 | 82.7 | 94.2 | 85.9 | 63.8 | 66.9 |

| TOOD [51] | 41.2 | 76.7 | 38.7 | 36.7 | 31.9 | 52.5 | 38.6 | 86.4 | 90.9 | 90.5 | 65.0 | 88.8 |

| Faster-RCNN [52] | 43.4 | 78.9 | 43.2 | 41.7 | 37.7 | 51.9 | 44.7 | 85.4 | 93.2 | 92.5 | 65.7 | 95.3 |

| DH-RCNN [53] | 36.7 | 75.0 | 33.5 | 40.3 | 29.1 | 40.7 | 40.4 | 79.4 | 87.6 | 88.5 | 63.0 | 91.2 |

| Cascade-RCNN [54] | 44.0 | 79.3 | 44.0 | 41.6 | 39.8 | 53.9 | 47.0 | 84.5 | 91.7 | 89.5 | 66.0 | 95.3 |

| Dynamic-RCNN [55] | 40.5 | 76.5 | 38.9 | 41.1 | 34.8 | 49.9 | 43.7 | 83.2 | 93.0 | 89.2 | 57.2 | 92.7 |

| Grid-RCNN [56] | 41.8 | 75.9 | 41.4 | 38.7 | 34.0 | 53.3 | 40.1 | 85.7 | 92.5 | 89.9 | 56.2 | 90.8 |

| Libra-RCNN [57] | 40.0 | 74.6 | 38.2 | 42.5 | 35.4 | 44.2 | 40.1 | 84.5 | 90.7 | 83.9 | 59.5 | 88.9 |

| Sparse-RCNN [58] | 39.7 | 71.3 | 39.6 | 35.9 | 33.1 | 47.9 | 37.4 | 80.8 | 89.1 | 90.1 | 49.3 | 81.1 |

| YOLOv9 [59] | 42.5 | 76.0 | 41.9 | 43.1 | 36.2 | 50.1 | 44.6 | 84.7 | 92.5 | 87.8 | 52.7 | 92.8 |

| YOLOv10 [60] | 41.3 | 77.3 | 41.5 | 42.6 | 38.2 | 49.6 | 45.4 | 82.4 | 91.7 | 90.4 | 62.9 | 90.8 |

| DETR [61] | 44.1 | 73.2 | 44.1 | 34.5 | 41.8 | 52.3 | 39.7 | 81.1 | 88.2 | 78.0 | 55.4 | 94.8 |

| RT-DETR [62] | 44.5 | 75.5 | 44.4 | 37.6 | 39.0 | 53.7 | 43.6 | 86.3 | 91.8 | 83.0 | 58.6 | 90.0 |

| CA-Autoassign [24] | 39.5 | 77.0 | 41.5 | 34.6 | 24.0 | 45.4 | 44.4 | 84.1 | 90.4 | 83.4 | 65.8 | 93.6 |

| STD2 [20] | 43.1 | 80.4 | 41.7 | 36.7 | 38.7 | 53.1 | 52.9 | 85.3 | 94.1 | 93.1 | 64.0 | 93.1 |

| Ours | 45.1 | 81.1 | 46.5 | 43.3 | 39.2 | 56.9 | 53.6 | 86.8 | 95.1 | 93.2 | 64.8 | 93.3 |

| Methods | AP | AP50 | AP75 | APS | APM | APL | Pu | Wl | Cg | Ws | Os | Ss | In | Rp | Cr | Wf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSD300 [50] | 27.8 | 58.1 | 20.1 | 8.7 | 24.5 | 29.4 | 93.6 | 76.4 | 90.8 | 73.5 | 55.1 | 60.0 | 37.3 | 14.5 | 44.8 | 35.4 |

| TOOD [51] | 34.5 | 65.2 | 31.3 | 12.6 | 28.9 | 39.0 | 93.2 | 79.8 | 90.1 | 76.5 | 66.0 | 59.7 | 26.2 | 33.5 | 55.9 | 70.7 |

| Faster-RCNN [52] | 34.2 | 68.0 | 29.6 | 10.2 | 30.5 | 34.2 | 95.7 | 95.2 | 90.5 | 76.2 | 65.0 | 63.1 | 37.6 | 48.8 | 37.2 | 70.5 |

| DH-RCNN [53] | 30.6 | 65.8 | 26.4 | 9.9 | 29.4 | 30.4 | 96.9 | 79.4 | 84.0 | 80.8 | 70.2 | 67.1 | 34.9 | 33.3 | 39.0 | 70.2 |

| Cascade-RCNN [54] | 34.8 | 69.9 | 30.9 | 11.9 | 30.0 | 38.7 | 94.5 | 96.9 | 88.6 | 75.0 | 71.3 | 63.7 | 38.0 | 46.5 | 50.4 | 73.8 |

| Dynamic-RCNN [55] | 30.3 | 62.2 | 23.9 | 10.6 | 29.9 | 30.6 | 97.2 | 96.4 | 86.5 | 69.3 | 67.8 | 57.9 | 31.4 | 25.9 | 31.0 | 58.5 |

| Grid-RCNN [56] | 30.1 | 63.1 | 24.2 | 11.3 | 28.7 | 30.9 | 96.3 | 92.3 | 85.6 | 67.3 | 69.4 | 54.2 | 30.5 | 32.3 | 37.2 | 68.0 |

| Libra-RCNN [57] | 27.5 | 57.9 | 22.1 | 12.9 | 28.9 | 26.6 | 97.4 | 93.6 | 88.2 | 67.4 | 65.3 | 54.8 | 17.5 | 18.2 | 27.0 | 49.9 |

| Sparse-RCNN [58] | 32.3 | 65.8 | 30.0 | 8.1 | 27.7 | 34.7 | 96.9 | 98.2 | 87.4 | 71.0 | 67.2 | 62.4 | 29.0 | 30.1 | 42.4 | 72.4 |

| YOLOv9 [59] | 33.6 | 67.6 | 31.5 | 14.2 | 29.7 | 35.9 | 91.5 | 82.8 | 92.9 | 79.6 | 70.0 | 66.8 | 25.7 | 41.1 | 56.1 | 70.8 |

| YOLOv10 [60] | 32.9 | 64.2 | 31.0 | 13.5 | 30.6 | 34.7 | 93.2 | 79.8 | 96.1 | 77.5 | 65.0 | 61.7 | 19.2 | 30.5 | 55.9 | 73.7 |

| DETR [61] | 31.7 | 68.8 | 30.1 | 12.1 | 27.0 | 36.9 | 95.8 | 90.3 | 90.9 | 80.4 | 55.4 | 60.1 | 43.0 | 43.3 | 55.4 | 71.5 |

| RT-DETR [62] | 30.1 | 69.7 | 22.3 | 11.6 | 25.5 | 35.0 | 96.7 | 88.7 | 92.1 | 80.4 | 62.3 | 65.2 | 41.5 | 45.3 | 55.0 | 70.1 |

| CA-Autoassign [24] | 24.3 | 62.6 | 27.5 | 9.7 | 22.7 | 32.9 | 95.9 | 77.7 | 92.7 | 70.5 | 62.0 | 61.7 | 35.3 | 31.8 | 32.5 | 65.7 |

| STD2 [20] | 35.0 | 71.0 | 29.8 | 12.1 | 32.0 | 38.3 | 95.6 | 96.5 | 87.0 | 77.7 | 70.8 | 63.9 | 42.3 | 48.5 | 56.4 | 70.0 |

| Ours | 35.9 | 72.3 | 30.0 | 14.1 | 31.5 | 40.1 | 97.4 | 98.3 | 88.6 | 78.9 | 67.9 | 67.8 | 43.7 | 50.6 | 56.5 | 72.8 |

| Methods | AP | AP50 | AP75 | APS | APM | APL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 43.4 | 78.9 | 43.2 | 41.7 | 37.7 | 51.9 |

| Baseline + CSSFAN | 44.5 | 80.0 | 45.4 | 42.4 | 38.1 | 54.2 |

| Baseline + ARPN | 43.9 | 79.8 | 44.3 | 42.6 | 38.9 | 53.6 |

| Baseline + CSSFAN + ARPN | 45.1 | 81.1 | 46.5 | 43.3 | 39.2 | 56.9 |

| Methods | AP | AP50 | AP75 | APS | APM | APL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPN [38] | 43.4 | 78.9 | 43.2 | 41.7 | 37.7 | 51.9 |

| NAS-FPN [39] | 41.7 | 77.1 | 42.4 | 40.2 | 34.9 | 49.5 |

| PAFPN [21] | 44.0 | 79.3 | 44.9 | 42.6 | 39.9 | 54.3 |

| BiFPN [40] | 42.9 | 78.5 | 47.1 | 42.3 | 38.7 | 53.6 |

| AFPN [63] | 42.6 | 76.3 | 40.2 | 40.0 | 35.1 | 50.3 |

| CSSFAN (Ours) | 45.1 | 81.1 | 46.5 | 43.3 | 39.2 | 56.9 |

| Methods | AP | AP50 | AP75 | APS | APM | APL | Pu | Wl | Cg | Ws | Os | Ss | In |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSD300 [50] | 66.0 | 95.5 | 79.4 | 39.5 | 55.7 | 67.0 | 95.7 | 98.3 | 96.8 | 93.8 | 97.6 | 94.7 | 91.7 |

| TOOD [51] | 70.5 | 95.9 | 86.2 | 48.3 | 64.8 | 71.5 | 97.5 | 98.4 | 95.0 | 96.4 | 98.0 | 96.1 | 90.1 |

| Faster-RCNN [52] | 68.3 | 95.7 | 82.4 | 41.7 | 63.1 | 69.2 | 95.4 | 96.9 | 96.7 | 95.4 | 95.5 | 95.5 | 93.6 |

| DH-RCNN [53] | 66.9 | 94.2 | 83.0 | 43.1 | 62.9 | 67.3 | 94.2 | 95.0 | 95.0 | 93.8 | 94.7 | 92.6 | 94.5 |

| Cascade-RCNN [54] | 69.9 | 96.5 | 85.4 | 43.2 | 67.9 | 70.6 | 95.5 | 98.9 | 96.8 | 96.0 | 97.4 | 95.6 | 95.0 |

| Dynamic-RCNN [55] | 62.1 | 91.8 | 80.0 | 40.6 | 57.5 | 64.1 | 91.1 | 93.3 | 92.6 | 90.4 | 92.5 | 91.3 | 91.4 |

| Grid-RCNN [56] | 63.7 | 93.8 | 81.5 | 41.6 | 60.3 | 65.9 | 95.2 | 96.4 | 93.3 | 94.7 | 95.2 | 94.1 | 88.1 |

| Libra-RCNN [57] | 60.6 | 90.7 | 76.3 | 42.1 | 51.5 | 62.5 | 91.7 | 93.4 | 91.9 | 90.3 | 92.5 | 89.5 | 96.4 |

| Sparse-RCNN [58] | 62.6 | 92.8 | 81.1 | 40.3 | 56.4 | 64.9 | 92.3 | 94.3 | 93.5 | 91.3 | 93.8 | 92.7 | 92.4 |

| YOLOv9 [59] | 65.5 | 94.5 | 70.6 | 44.1 | 57.7 | 61.4 | 94.8 | 97.2 | 95.7 | 92.8 | 96.7 | 93.6 | 90.8 |

| YOLOv10 [60] | 66.1 | 94.7 | 80.1 | 40.6 | 61.9 | 65.2 | 94.5 | 95.8 | 95.6 | 94.5 | 95.3 | 94.7 | 92.6 |

| DETR [61] | 64.5 | 92.9 | 83.1 | 46.3 | 61.5 | 68.2 | 94.3 | 95.2 | 92.2 | 93.5 | 95.1 | 93.1 | 87.0 |

| RT-DETR [62] | 67.2 | 95.4 | 81.8 | 45.5 | 54.1 | 68.3 | 96.7 | 98.5 | 95.7 | 95.2 | 96.0 | 94.7 | 91.1 |

| CA-Autoassign [24] | 67.6 | 95.7 | 81.4 | 47.3 | 56.8 | 68.5 | 96.5 | 98.6 | 96.8 | 95.4 | 96.3 | 94.9 | 91.2 |

| STD2 [20] | 68.1 | 96.8 | 84.0 | 44.6 | 62.5 | 69.1 | 96.4 | 98.0 | 97.8 | 95.8 | 97.5 | 96.1 | 96.0 |

| Ours | 70.9 | 97.2 | 87.6 | 47.6 | 67.7 | 71.8 | 96.1 | 99.0 | 98.0 | 96.2 | 97.6 | 96.6 | 97.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, C.; Sun, Y.; Huang, L.; Guo, H. A Cross-Scale Spatial–Semantic Feature Aggregation Network for Strip Steel Surface Defect Detection. Materials 2025, 18, 5567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245567

Xu C, Sun Y, Huang L, Guo H. A Cross-Scale Spatial–Semantic Feature Aggregation Network for Strip Steel Surface Defect Detection. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245567

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Chenglong, Yange Sun, Linlin Huang, and Huaping Guo. 2025. "A Cross-Scale Spatial–Semantic Feature Aggregation Network for Strip Steel Surface Defect Detection" Materials 18, no. 24: 5567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245567

APA StyleXu, C., Sun, Y., Huang, L., & Guo, H. (2025). A Cross-Scale Spatial–Semantic Feature Aggregation Network for Strip Steel Surface Defect Detection. Materials, 18(24), 5567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245567