Role of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process Factors in Determining the Porosity Formation in 3D Printing of Stainless Steel 316L: Theoretical Modeling and Experimental Verification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Development Theoretical Framework

2.1. Modeling of Porosity

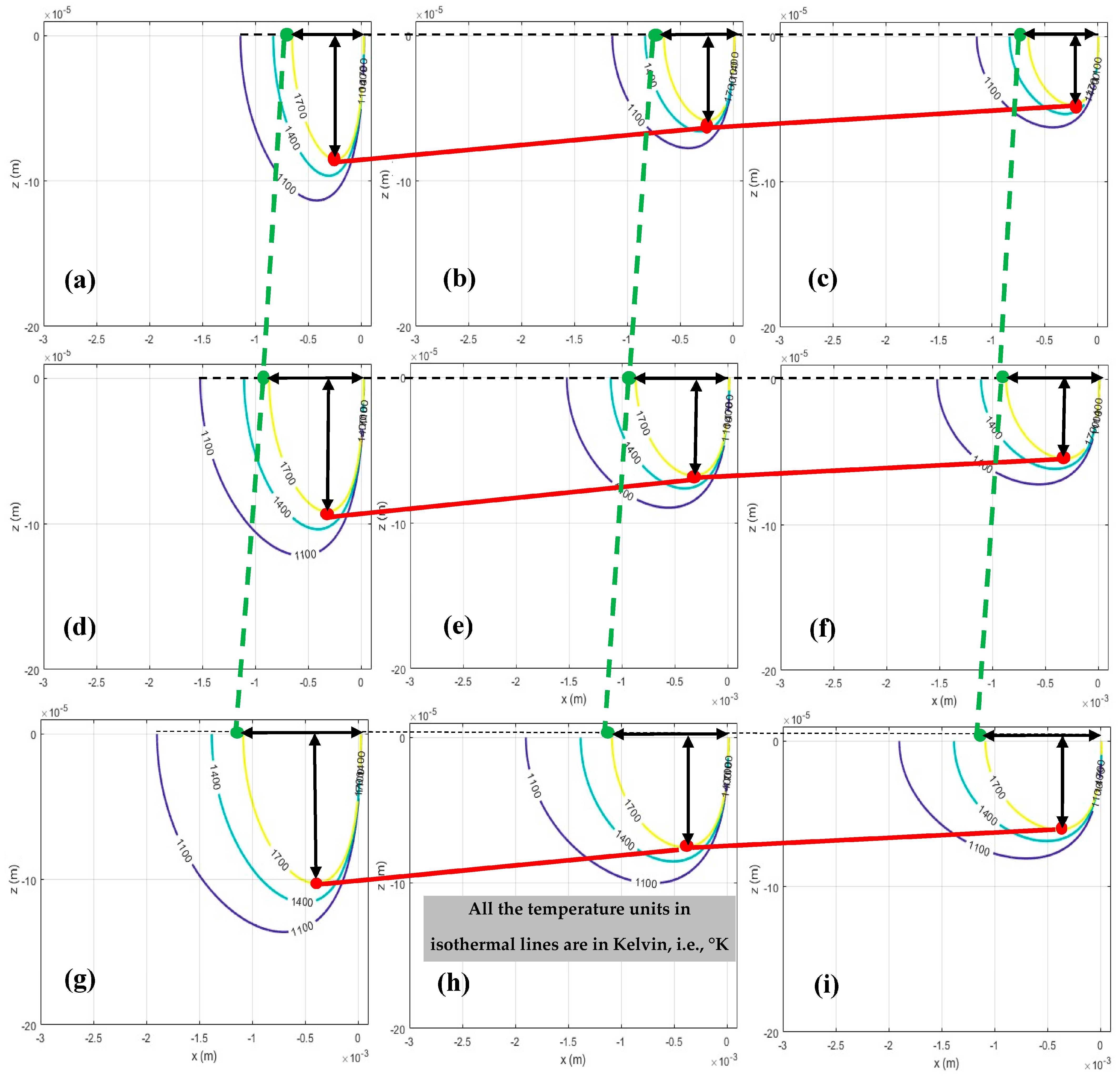

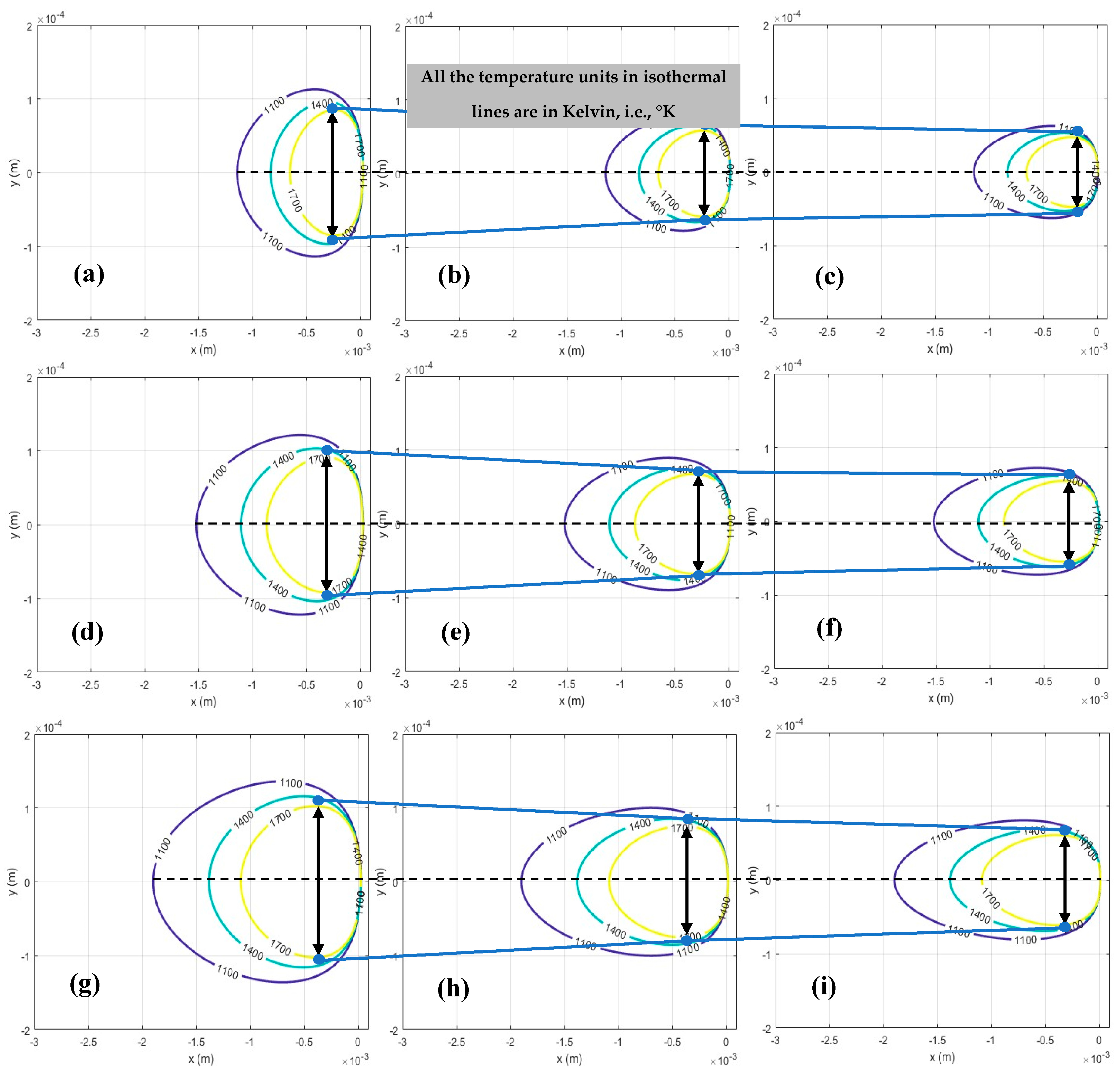

2.1.1. Prediction of Melt Pool Geometry

2.1.2. Prediction of Keyhole Porosity

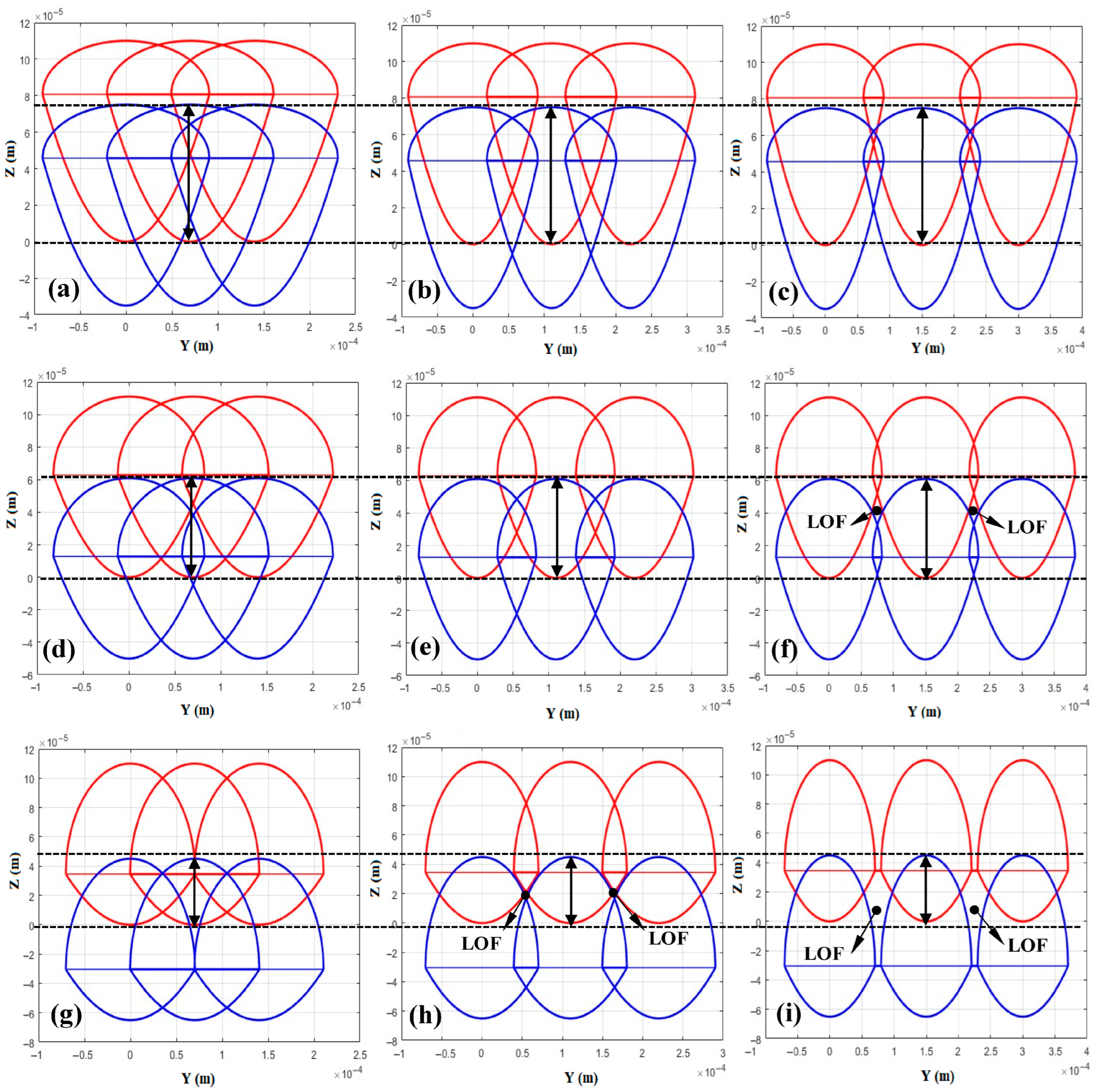

2.1.3. Prediction of Lack-of-Fusion Porosity

3. Experimental Work

4. Calibration and Sensitivity Analysis

4.1. Calibration of Bubble Radius

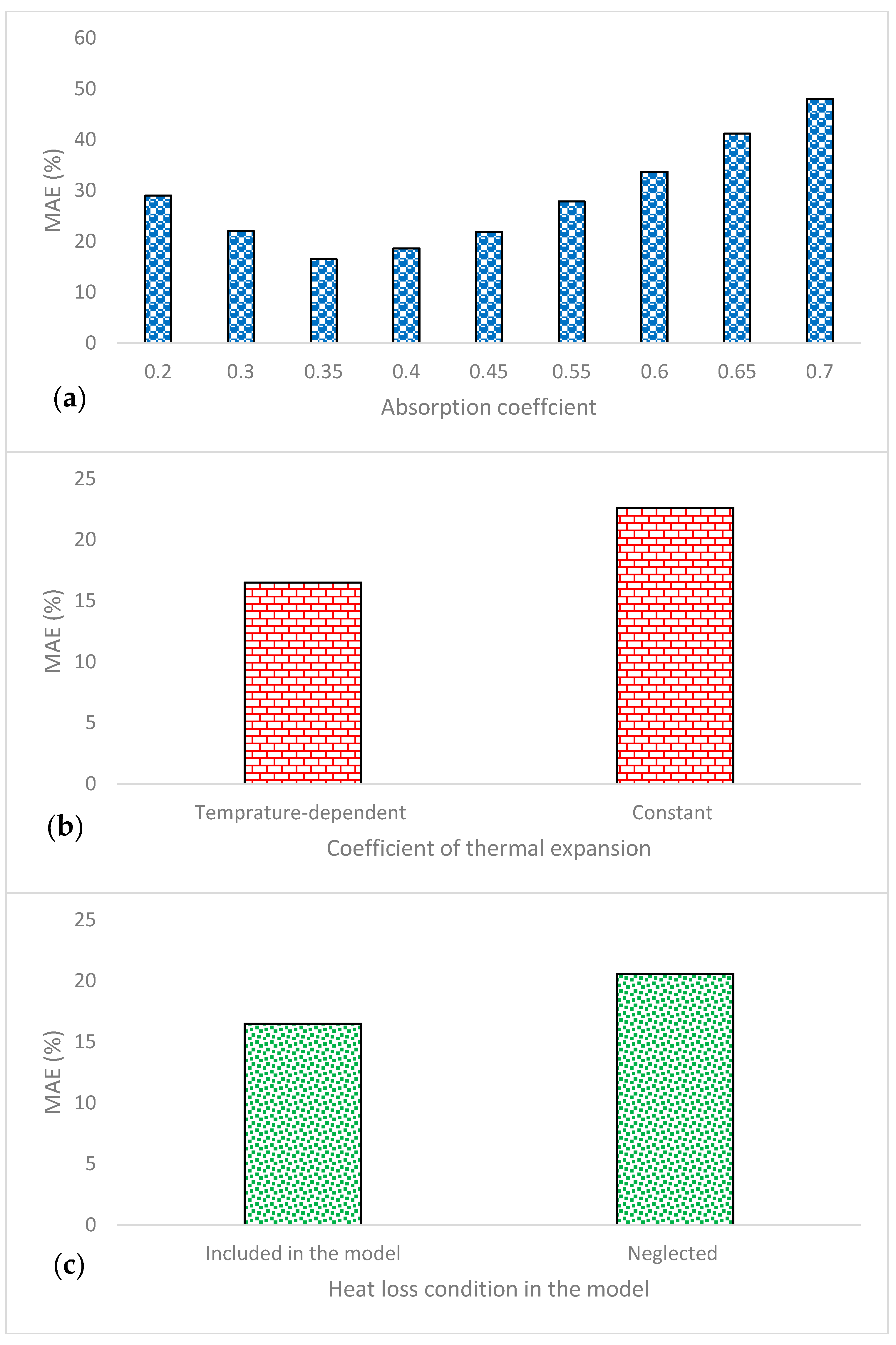

4.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Coefficients and Constants

5. Results and Discussion

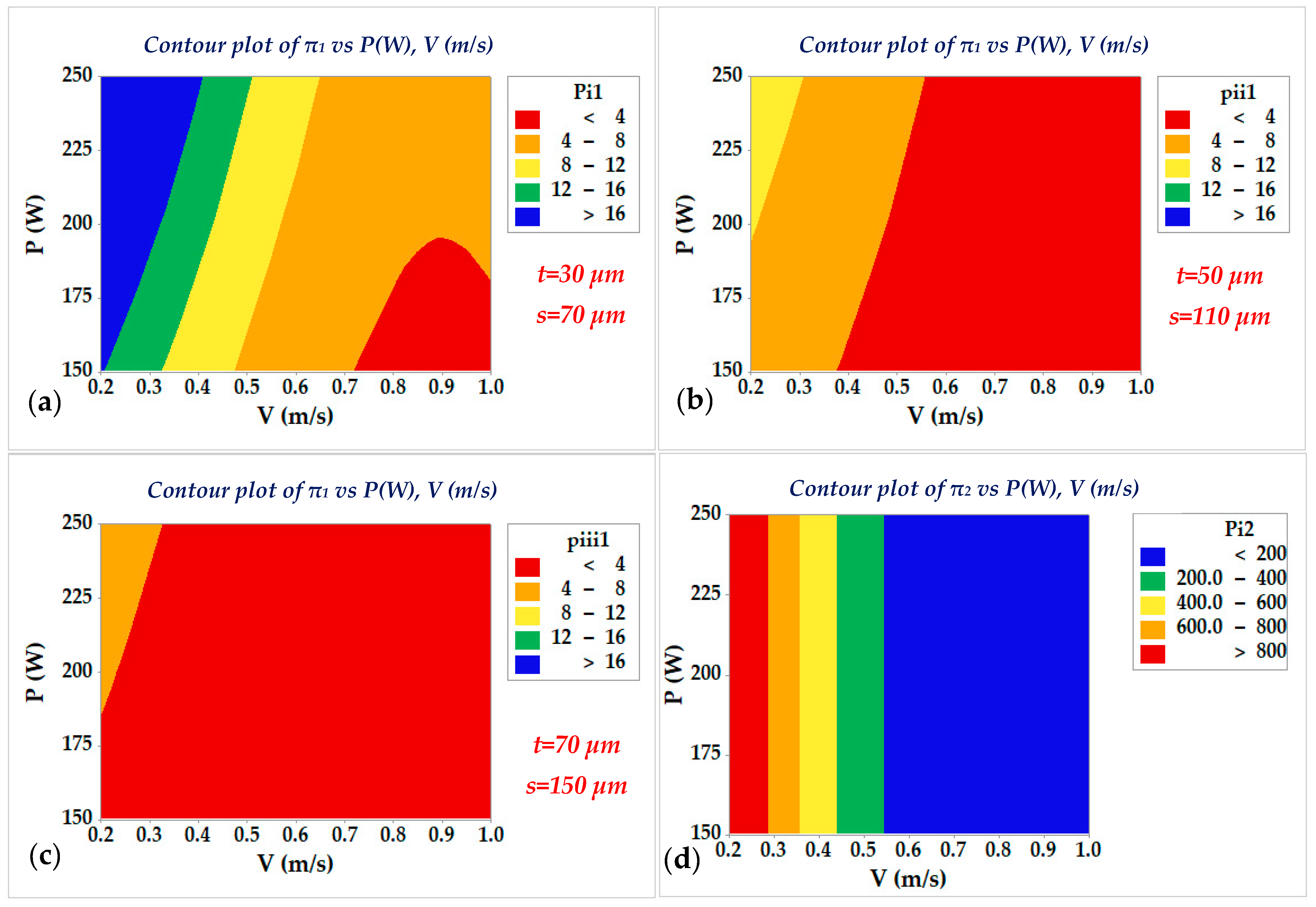

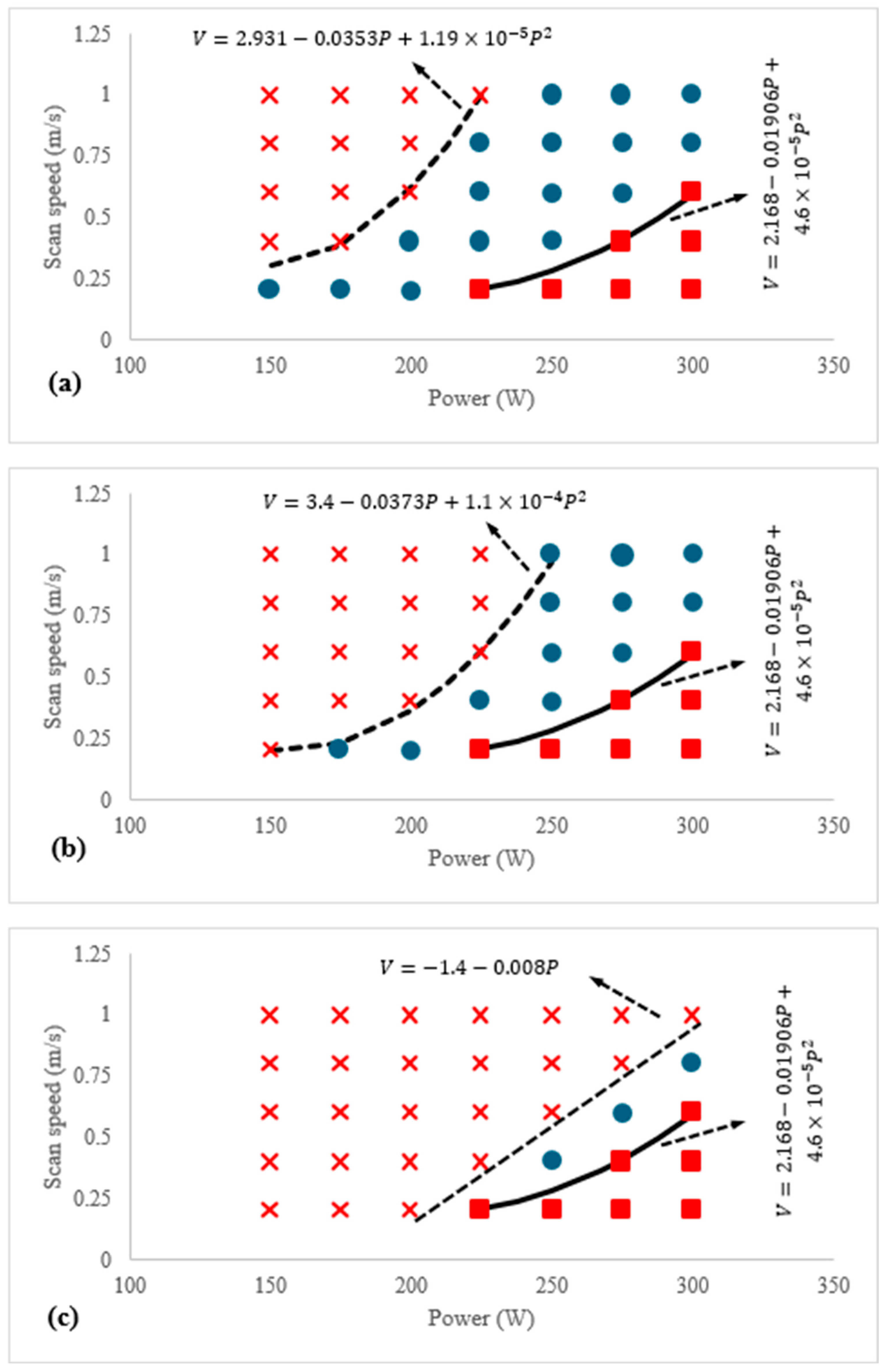

5.1. Paramertric Influence

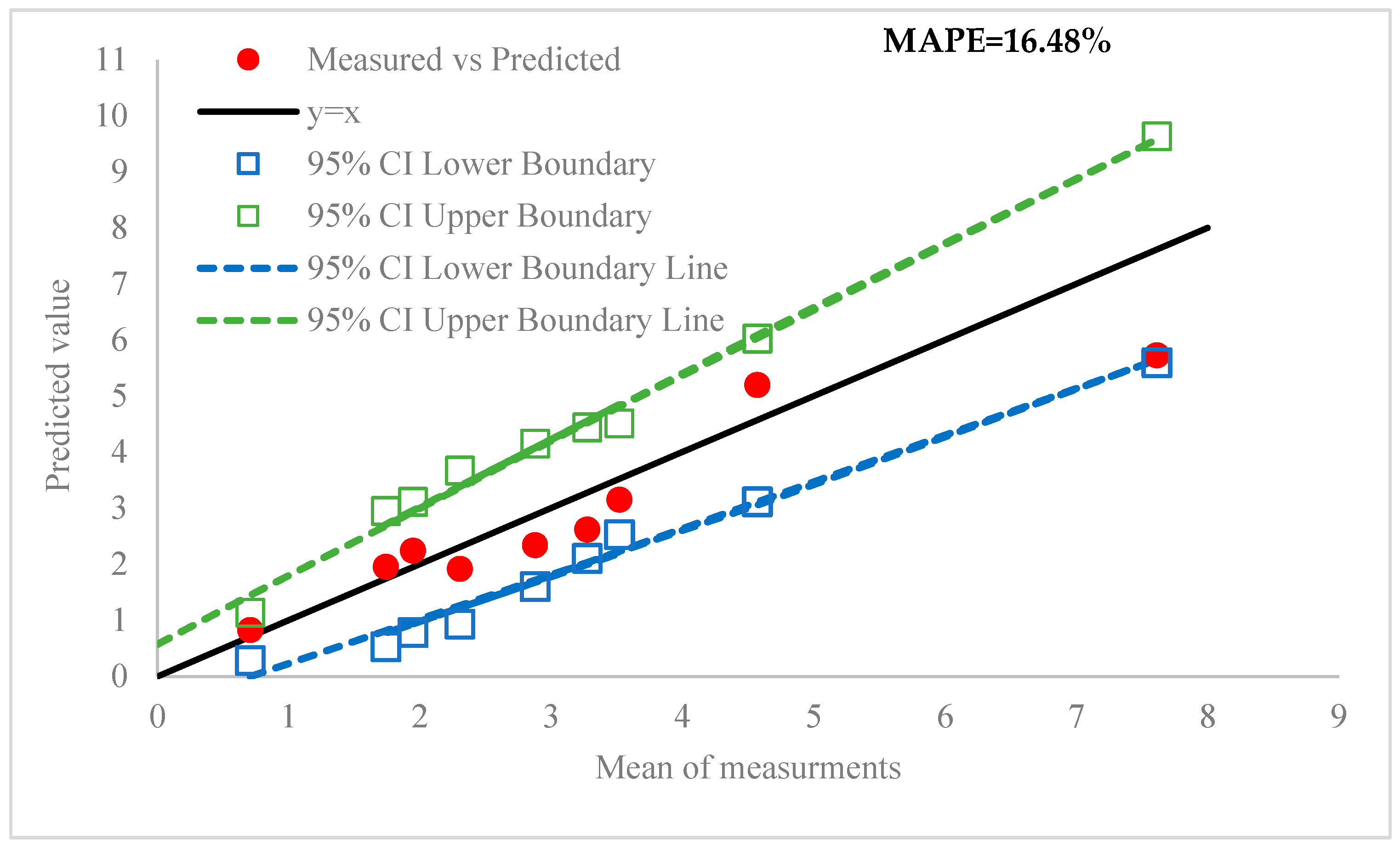

5.2. Confirmation

6. Conclusions

- Analysis indicated that increasing the energy density, either by reducing scan speed or increasing laser power, initially reduces LOF porosity. Beyond a certain threshold, further increases in energy density led to higher porosity due to keyhole formation.

- Increasing layer thickness was found to increase LOF porosity and reduce interlayer bonding. Similarly, increasing hatch distance also raises LOF. However, at high energy densities, the melt pool becomes sufficiently large, and variations in layer thickness or hatch distance have a limited impact on LOF porosity.

- It should be noted that, since in this work the bubble radius is determined using an empirical approach, our computational framework for porosity prediction can be classified as semi-analytical when the process parameters are designed such that keyhole formation becomes dominant. Nevertheless, the development of a fully predictive model remains an open issue, particularly concerning the modeling and calibration of bubble size and its relationship with the printing parameters.

- Future work will focus on extending the current process porosity model to include detailed porosity descriptors (size distribution, shape, anisotropy, and tortuosity), aiming to capture the chaotic nature of pore formation and improve the physical interpretability of the model.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, C.; Wang, D.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Cheng, L.; Fang, C.; Zhang, Y. Twin-channel attention-based convolutional neural network for layer-wise prediction of surface roughness in the laser powder bed fusion process. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 230, 112581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoqi, Z.; Gaikwad, A.; Bevans, B.; Kobir, M.H.; Craig, J.; Abul-Haj, A.; Peralta, A.; Rao, P. Monitoring and prediction of porosity in laser powder bed fusion using physics-informed meltpool signatures and machine learning. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 304, 117550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Lin, H.; Yu, C.X.; Frye, R.; Beckett, D.; Anderson, K.; Jacquemetton, L.; Carter, F.; Gao, Z.; Liao, W.-K.; et al. A deep learning framework for layer-wise porosity prediction in metal powder bed fusion using thermal signatures. J. Intell. Manuf. 2023, 34, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwya, M.; Panoutsos, G. In-situ porosity prediction in metal powder bed fusion additive manufacturing using spectral emissions: A prior-guided machine learning approach. J. Intell. Manuf. 2024, 35, 2719–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.; Brandt, M.; Trinchi, A.; Sola, A.; Molotnikov, A. Process monitoring and machine learning for defect detection in laser-based metal additive manufacturing. J. Intell. Manuf. 2024, 35, 1407–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Fang, G.; Lei, L.; Yan, X. Predicting the porosity defects in selective laser melting (SLM) by molten pool geometry. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 228, 107478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vastola, G.; Pei, Q.X.; Zhang, Y.W. Predictive model for porosity in powder-bed fusion additive manufacturing at high beam energy regime. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 22, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiarian, M.; Omidvar, H.; Mashhuriazar, A.; Sajuri, Z.; Gur, C.H. The effects of SLM process parameters on the relative density and hardness of austenitic stainless steel 316L. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 1616–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promoppatum, P.; Srinivasan, R.; Quek, S.S.; Msolli, S.; Shukla, S.; Johan, N.S.; van der Veen, S.; Jhon, M.H. Quantification and prediction of lack-of-fusion porosity in the high porosity regime during laser powder bed fusion of Ti-6Al-4V. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 300, 117426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ning, J.; Liang, S.Y. Prediction of lack-of-fusion porosity in laser powder-bed fusion considering boundary conditions and sensitivity to laser power absorption. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 112, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Wang, W.; Zamorano, B.; Liang, S.Y. Analytical modeling of lack-of-fusion porosity in metal additive manufacturing. Appl. Phys. A 2019, 125, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Sievers, D.E.; Garmestani, H.; Liang, S.Y. Analytical modeling of part porosity in metal additive manufacturing. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2020, 172, 105428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, T.; DebRoy, T. Mitigation of lack of fusion defects in powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. J. Manuf. Process. 2018, 36, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Pistorius, P.C.; Beuth, J.L. Prediction of lack-of-fusion porosity for powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 14, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Tan, J.L.; Wong, C.H. A numerical investigation on the physical mechanisms of single track defects in selective laser melting. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 126, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liang, S.Y. A 3D analytical modeling method for keyhole porosity prediction in laser powder bed fusion. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 120, 3017–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, W.E.; Barth, H.D.; Castillo, V.M.; Gallegos, G.F.; Gibbs, J.W.; Hahn, D.E.; Kamath, C.; Rubenchik, A.M. Observation of keyhole-mode laser melting in laser powder-bed fusion additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2014, 214, 2915–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, T.; Wei, H.L.; De, A.; DebRoy, T. Heat and fluid flow in additive manufacturing—Part I: Modeling of powder bed fusion. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2018, 150, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, T.; Wei, H.L.; De, A.; DebRoy, T. Heat and fluid flow in additive manufacturing—Part II: Powder be fusion of stainless steel, and titanium, nickel and aluminum base alloys. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2018, 150, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Qi, Y.; Chen, C.; Nie, X.; Wang, J.; Zhu, H. Analytical model of predicting residual stress-process parameter relationship for laser powder bed fusion of Ti6Al4V. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 35, 6372–6382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprio, L.; Demir, A.G.; Previtali, B. Observing molten pool surface oscillations during keyhole processing in laser powder bed fusion as a novel method to estimate the penetration depth. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimouri, R.; Sohrabpoor, H.; Grabowski, M.; Wyszyński, D.; Skoczypiec, S.; Raghavendra, R. Simulation of surface roughness evolution of additively manufactured material fabricated by laser powder bed fusion and post-processed by burnishing. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 84, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, R.; Zhao, C.; Parab, N.; Kantzos, C.; Pauza, J.; Fezzaa, K.; Sun, T.; Rollett, A.D. Keyhole threshold and morphology in laser melting revealed by ultrahigh-speed x-ray imaging. Science 2019, 363, 849–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference | Type of Modeled Porosity | Modeling Strategy | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wang and Liang [10] | Lack-of-fusion | Analytical |

|

| Ning et al. [11] | Lack-of-fusion | Analytical |

|

| Ning et al. [12] | Lack-of-fusion | Analytical |

|

| Tang et al. [14] | Lack-of-fusion | FEM |

|

| Wang and Liang [16] | Keyhole | Analytical |

|

| King et al. [17] | Keyhole | FEM |

|

| Properties | Symbol | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density of solid | ρs | Kg/m3 | 8084 − 0.4209T − 3.894 × 10−3T |

| Density of liquid | ρc | Kg/m3 | 7433 − 0.0393T − 1.8 × 10−2T |

| Specific heat of solid | Cs | J/kg°K | 462 + 0.134T |

| Specific heat of liquid | CL | J/kg°K | 775 |

| Thermal conductivity of solid | Ks | W/m°K | 9.248 + 0.01571T |

| Thermal conductivity of liquid | KL | W/m°K | 12.41 + 0.00327T |

| Melting temperature | Tm | °K | 1723 |

| Evaporation temperature | Tv | °K | 3090 |

| Viscosity of liquid metal | µ | Kg/ms | 10(2358.2/T − 3.5958) |

| Surface tension | γ | Kg/s2 | 1.87 |

| Absorptivity | η | 0.35 |

| Element | C | Si | Mn | P | S | Cr | Ni | Mo | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt.% | 0.03 | 0.75 | 2.0 | 0.045 | 0.03 | 16–18 | 10–14 | 2–3 | Balance |

| No | P (W) | V (m/s) | t (μm) | s (μm) | VED (J/mm3) | Measured Porosity (%) | Predicted Porosity (%) | Error with Respect to Mean Value (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||

| 1 | 150 | 0.20 | 30 | 70 | 357.14 | 0.68 | 0.89 | 0.55 | 0.827 | 17.1 |

| 2 | 150 | 0.6 | 50 | 110 | 45.45 | 4.32 | 5.24 | 4.15 | 5.196 | 13.7 |

| 3 | 150 | 1 | 70 | 150 | 14.29 | 7.44 | 8.5 | 6.9 | 5.726 | 24.78 |

| 4 | 200 | 0.20 | 50 | 150 | 133.33 | 2.25 | 1.78 | 2.88 | 1.916 | 16.8 |

| 5 | 200 | 0.6 | 70 | 70 | 68.03 | 3.16 | 3.45 | 3.95 | 3.15 | 10.5 |

| 6 | 200 | 1 | 30 | 110 | 60.61 | 3.41 | 2.75 | 3.66 | 2.618 | 20 |

| 7 | 250 | 0.2 | 70 | 110 | 162.34 | 1.87 | 1.52 | 2.45 | 2.241 | 15.2 |

| 8 | 250 | 0.6 | 30 | 150 | 92.59 | 1.61 | 1.33 | 2.28 | 1.954 | 12.3 |

| 9 | 250 | 1 | 50 | 70 | 71.43 | 2.95 | 2.33 | 3.35 | 2.34 | 18.4 |

| No | Mean Value (%) | Standard Deviation | Lower CI | Upper CI | Predicted Value (%) | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.7067 | 0.17155 | 0.2807 | 1.1326 | 0.827 | 17.1 |

| 2 | 4.57 | 0.58645 | 3.1141 | 6.0259 | 5.196 | 13.7 |

| 3 | 7.6133 | 0.81395 | 5.5926 | 9.6341 | 5.726 | 24.78 |

| 4 | 2.3033 | 0.55195 | 0.9331 | 3.6736 | 1.916 | 16.8 |

| 5 | 3.52 | 0.3996 | 2.5279 | 4.5121 | 3.15 | 10.5 |

| 6 | 3.2733 | 0.47015 | 2.1062 | 4.4405 | 2.618 | 20 |

| 7 | 1.9467 | 0.4697 | 0.7805 | 3.1128 | 2.241 | 15.2 |

| 8 | 1.74 | 0.48815 | 0.5281 | 2.9519 | 1.954 | 12.3 |

| 9 | 2.8767 | 0.51395 | 1.6008 | 4.1526 | 2.34 | 18.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stwora, A.; Teimouri, R.; Habel, J. Role of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process Factors in Determining the Porosity Formation in 3D Printing of Stainless Steel 316L: Theoretical Modeling and Experimental Verification. Materials 2025, 18, 5490. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245490

Stwora A, Teimouri R, Habel J. Role of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process Factors in Determining the Porosity Formation in 3D Printing of Stainless Steel 316L: Theoretical Modeling and Experimental Verification. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5490. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245490

Chicago/Turabian StyleStwora, Andrzej, Reza Teimouri, and Jacek Habel. 2025. "Role of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process Factors in Determining the Porosity Formation in 3D Printing of Stainless Steel 316L: Theoretical Modeling and Experimental Verification" Materials 18, no. 24: 5490. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245490

APA StyleStwora, A., Teimouri, R., & Habel, J. (2025). Role of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process Factors in Determining the Porosity Formation in 3D Printing of Stainless Steel 316L: Theoretical Modeling and Experimental Verification. Materials, 18(24), 5490. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245490