Comparative Study on the Wear Resistance of C&B-Type Polymer Materials for Temporary Crowns Manufactured Using 3D DLP Printing Technology

Highlights

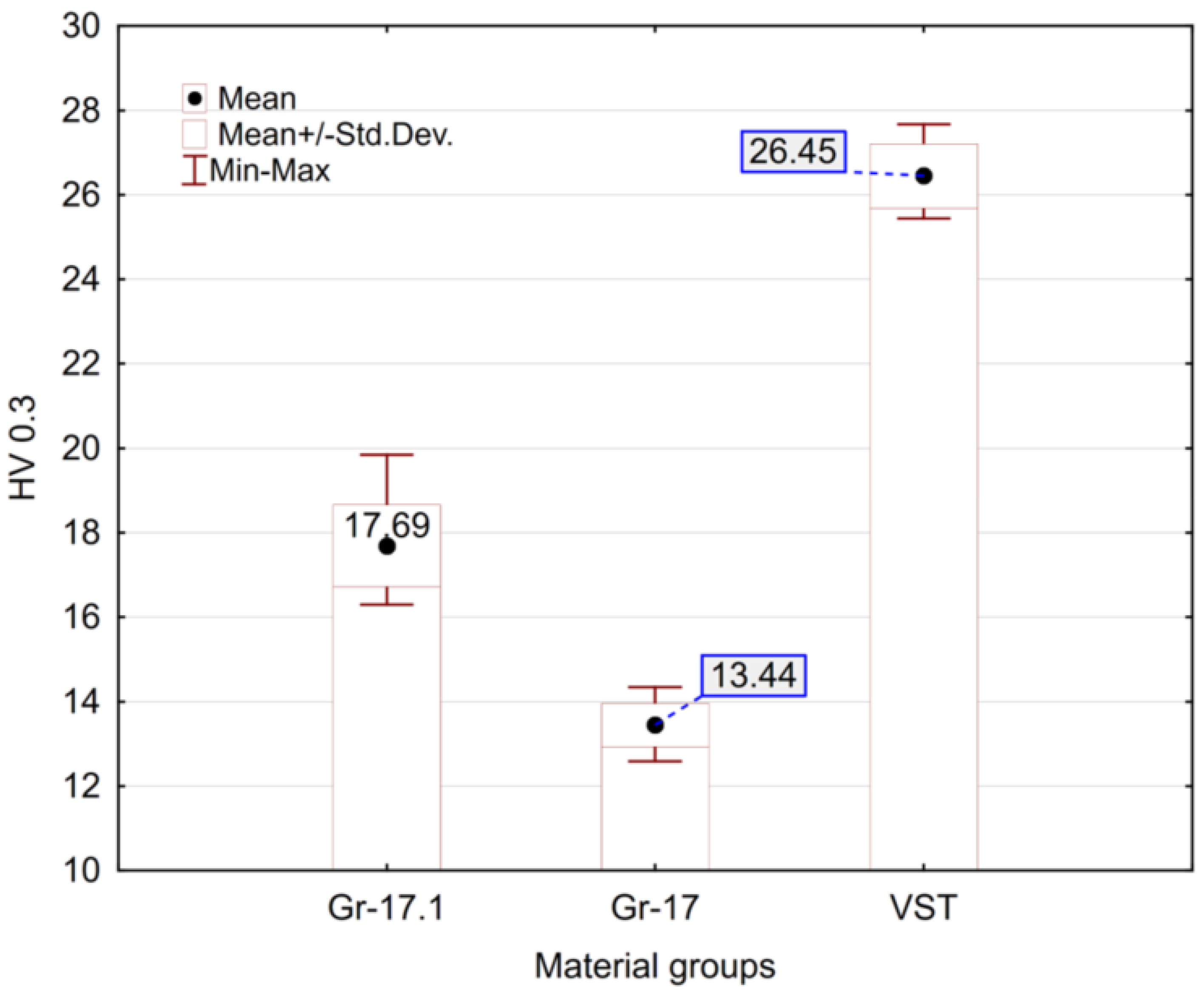

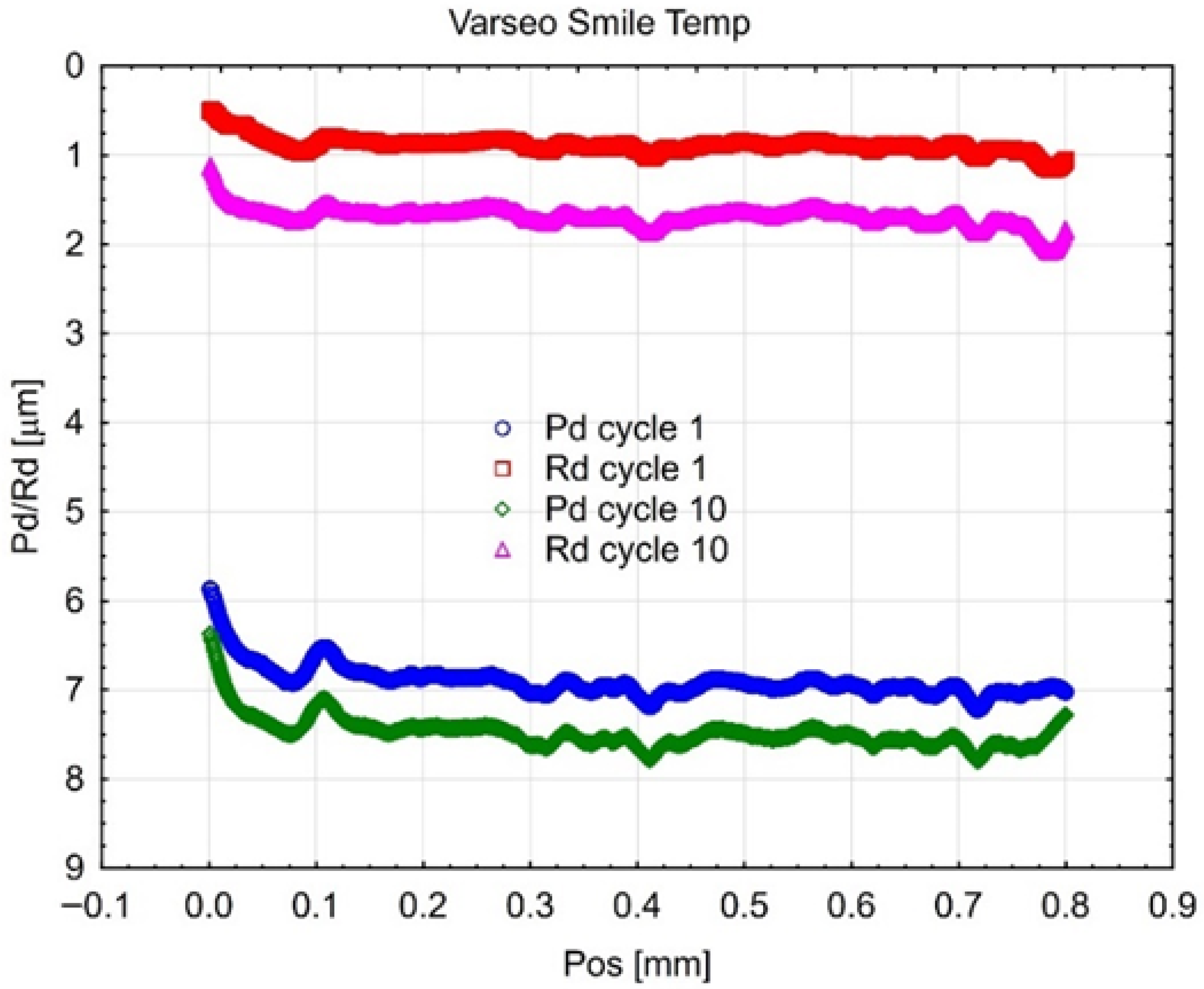

- VarseoSmile Temp had the lowest wear and highest scratch resistance.

- Wear resistance depends on the amount of filler and microstructure.

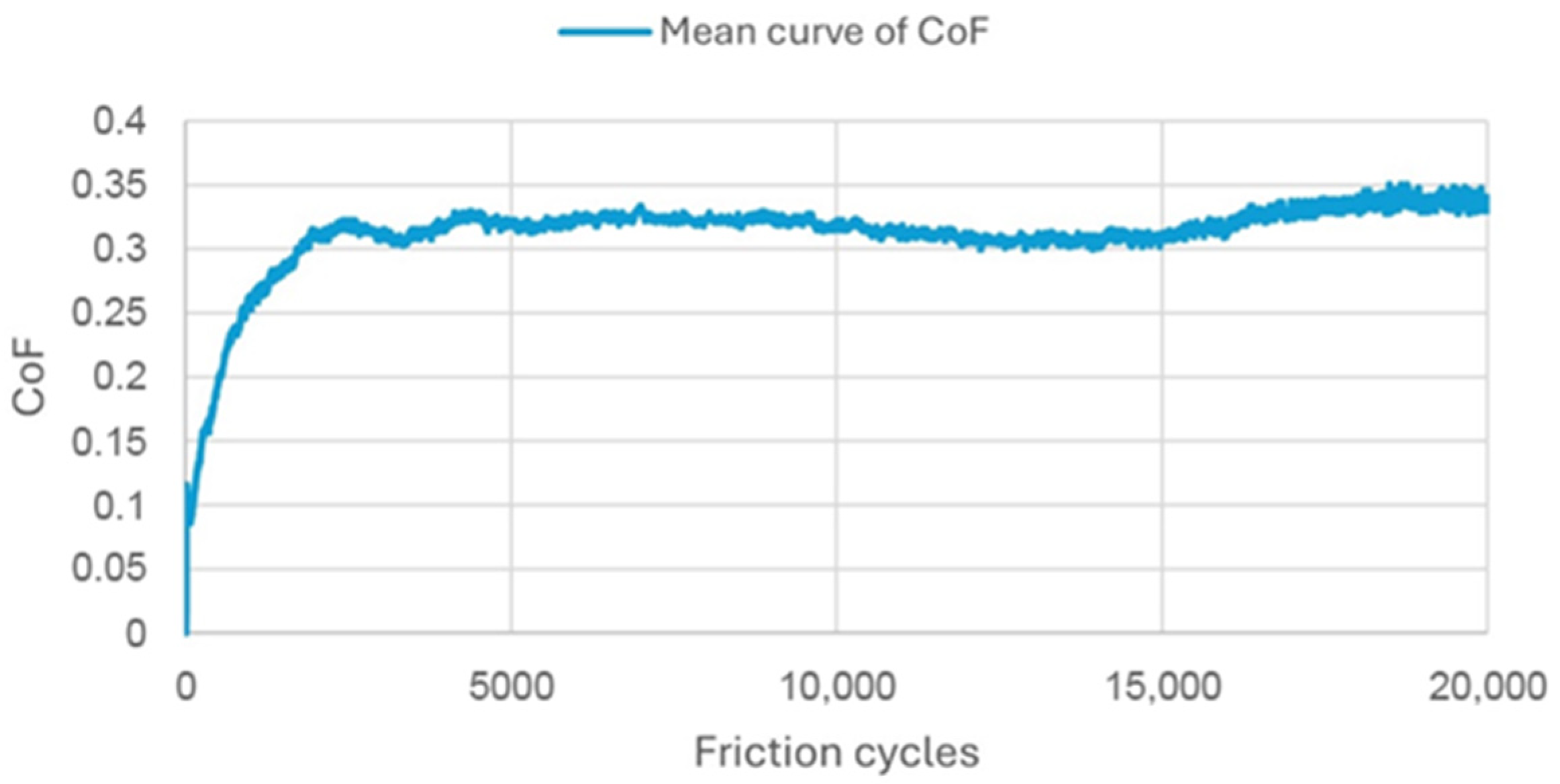

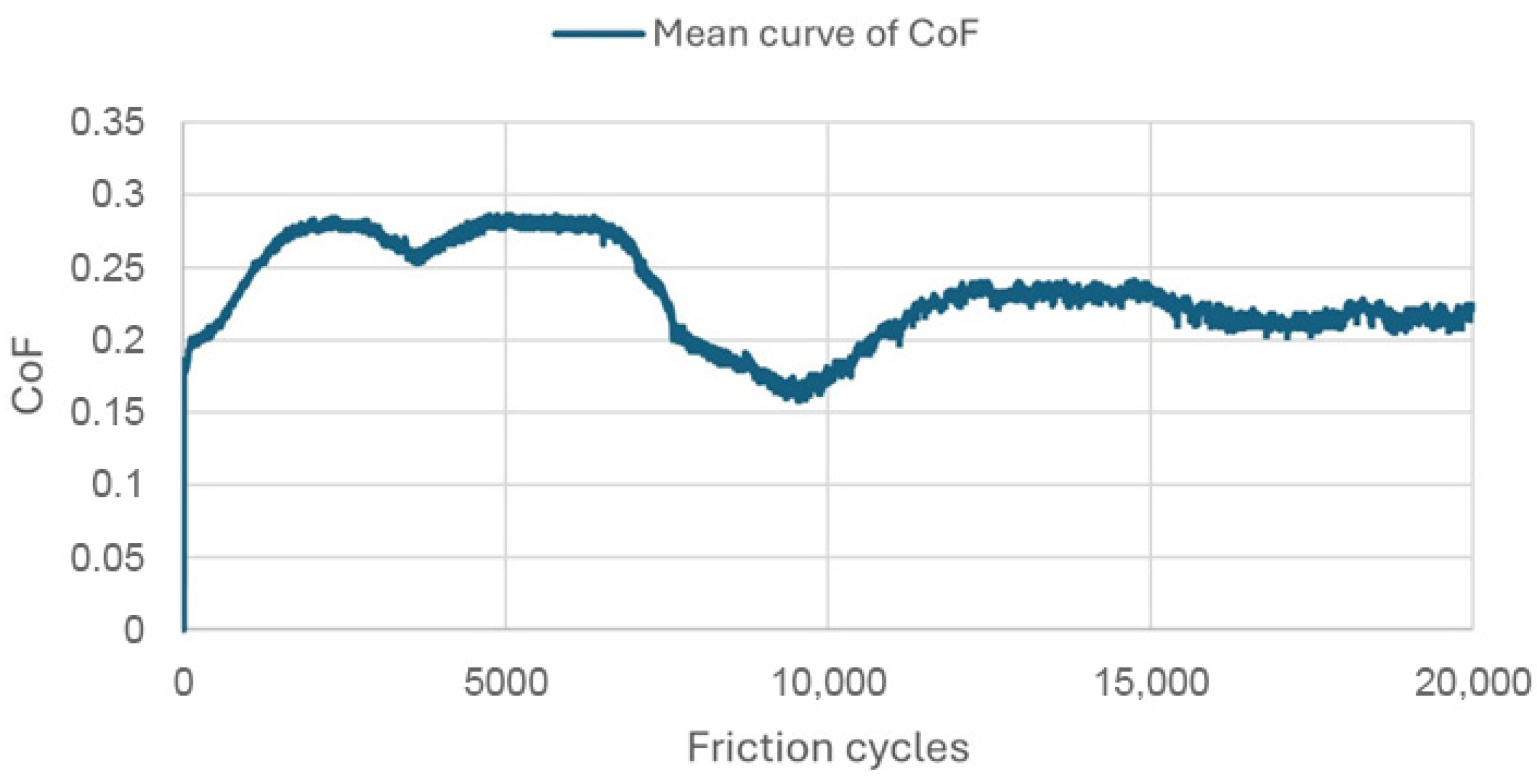

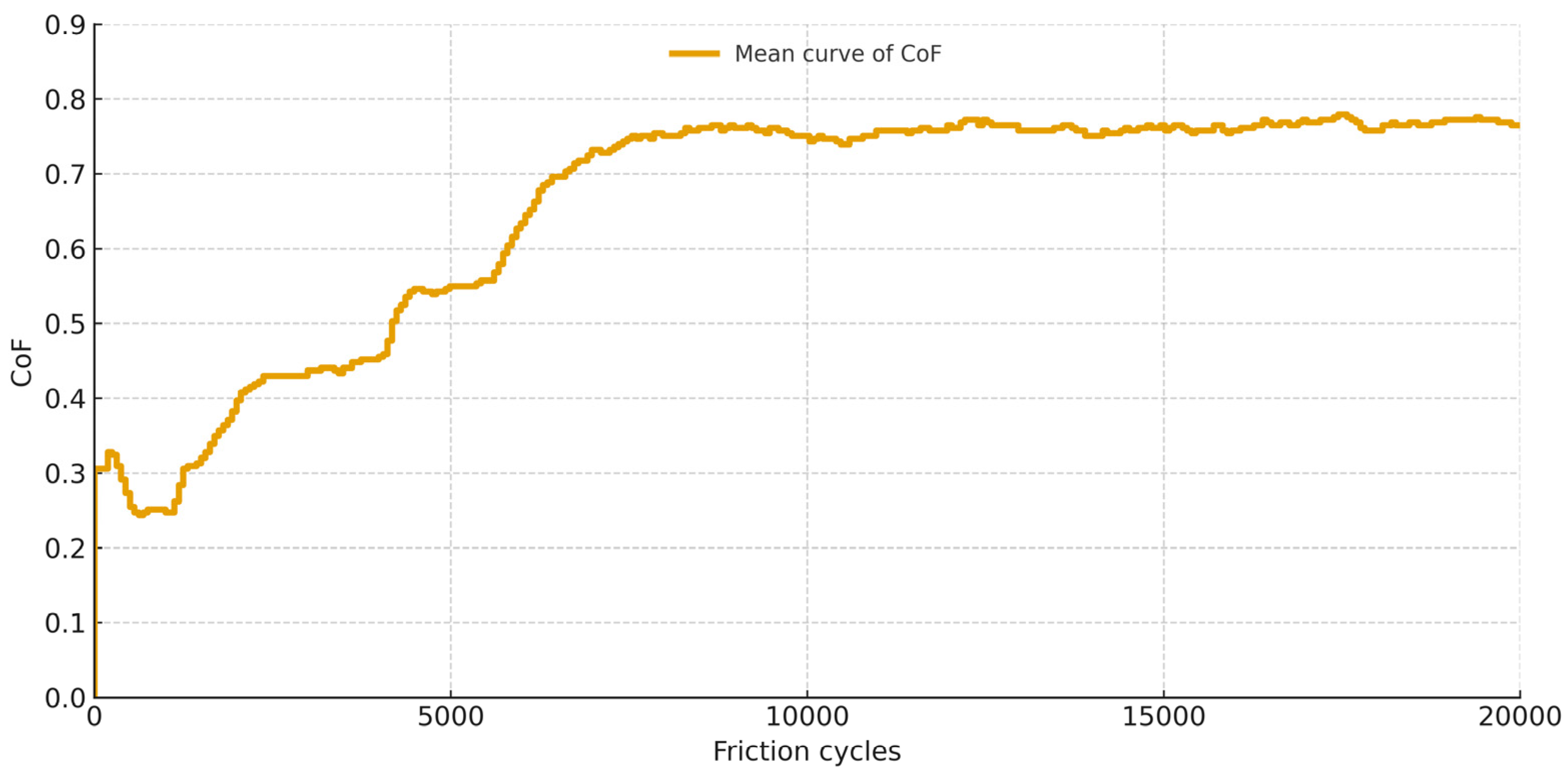

- No direct relationship was found between the coefficient of friction and wear.

- Higher inorganic filler content improved surface elasticity.

- VarseoSmile Temp is best suited for temporary crowns with long-term stability.

- Tribological testing allows for the prediction of clinical behavior of 3D printed materials.

- Optimization of the filler improves functional and durability indicators.

- Test results in a humid, 37 °C environment reliably reflect oral conditions.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

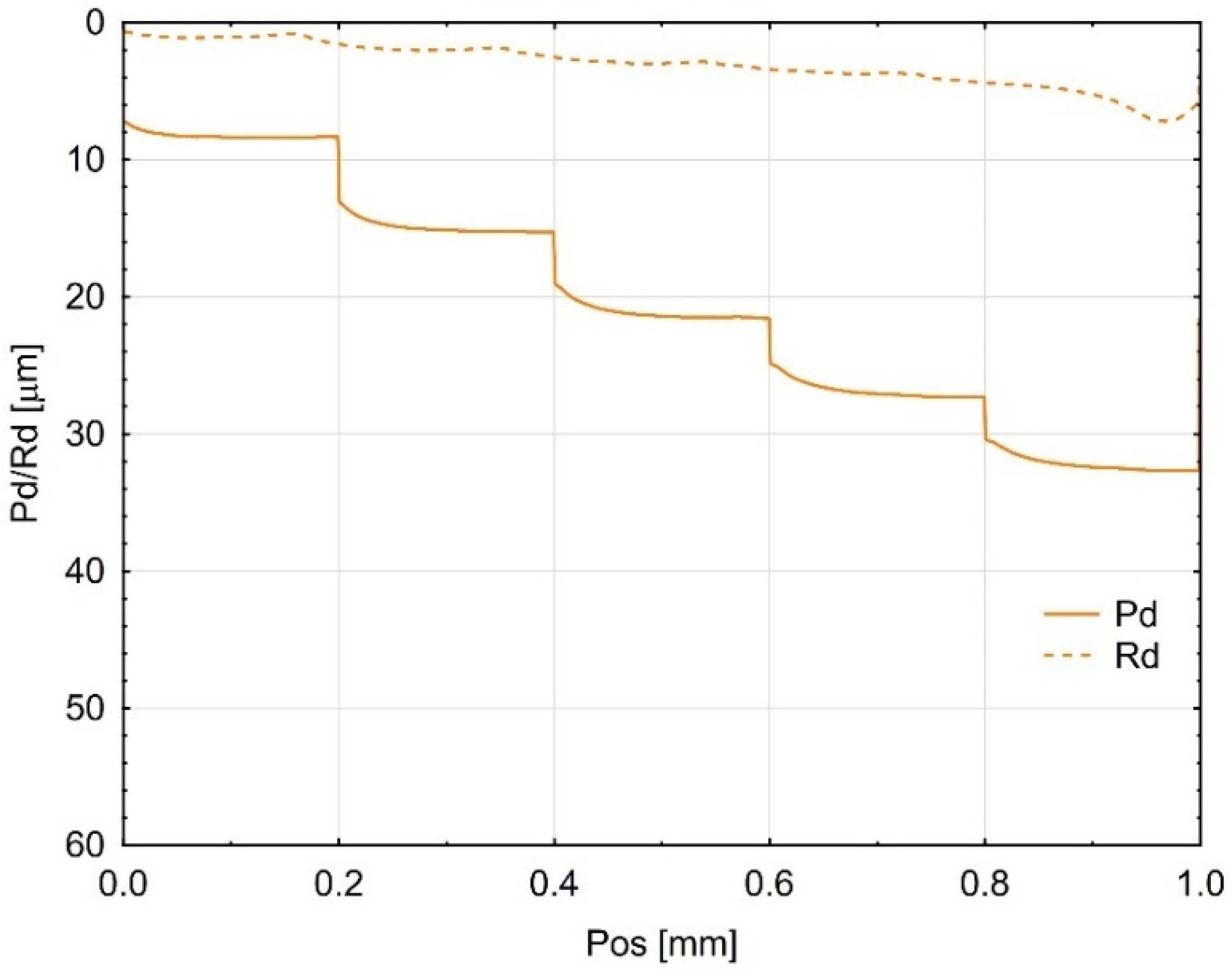

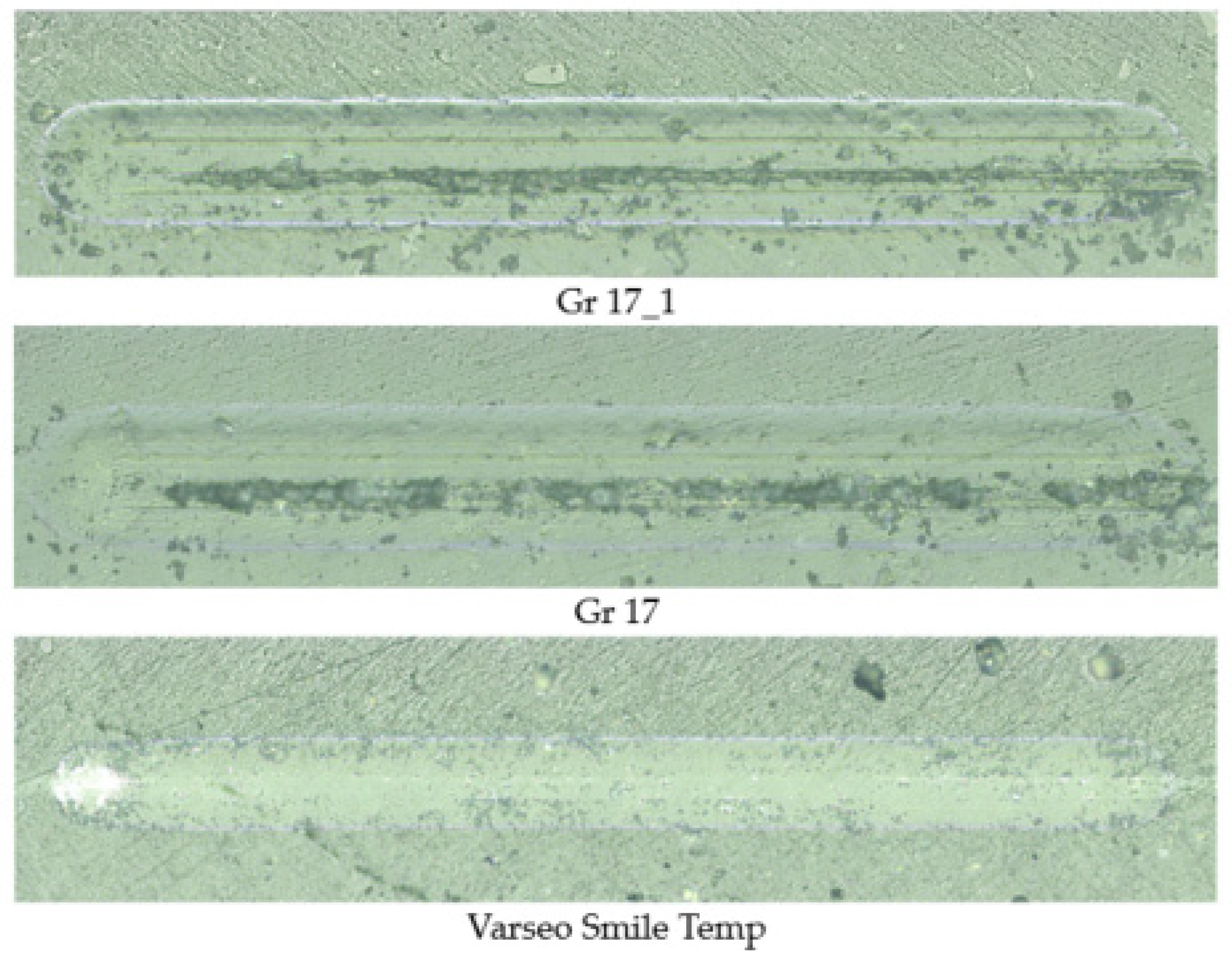

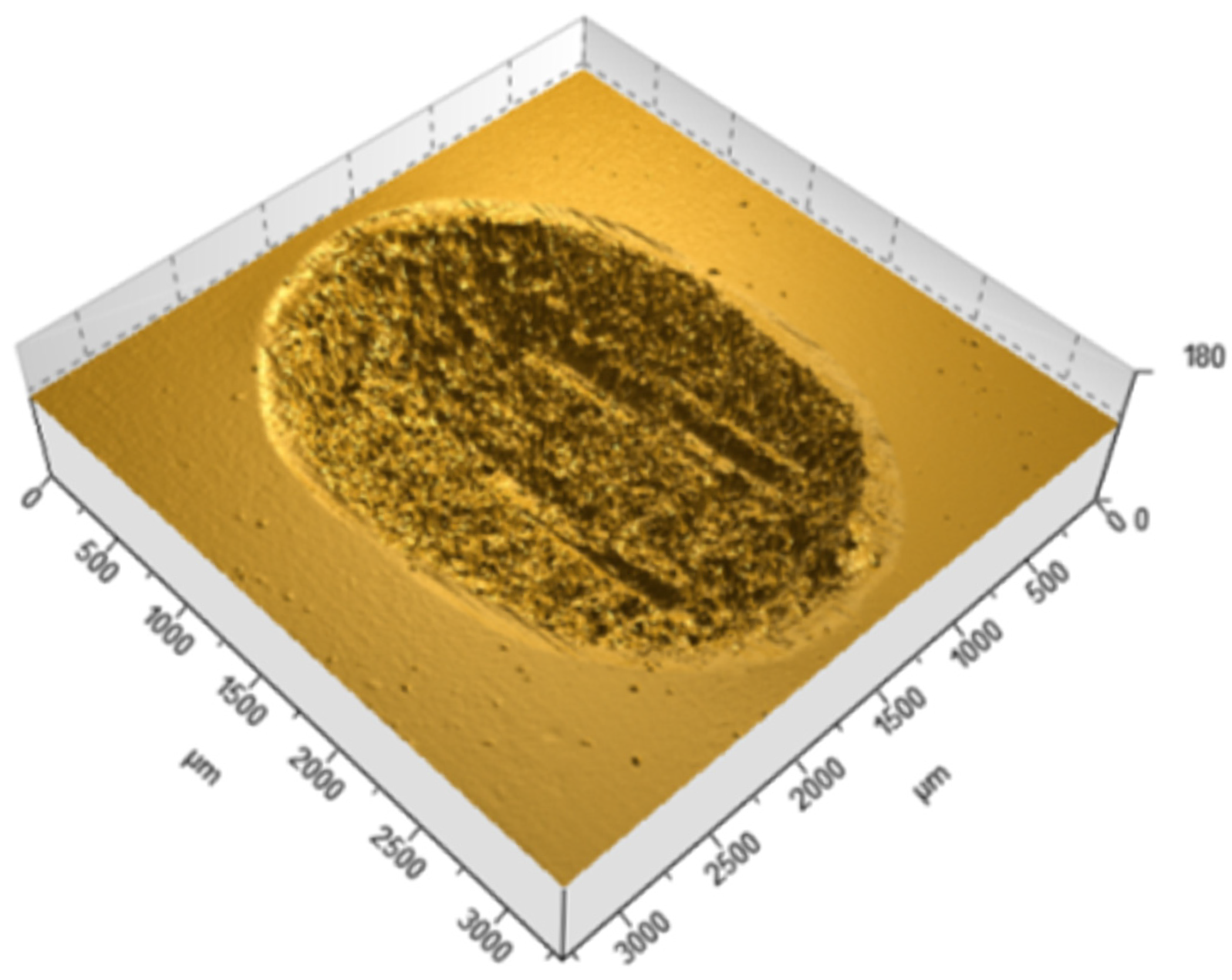

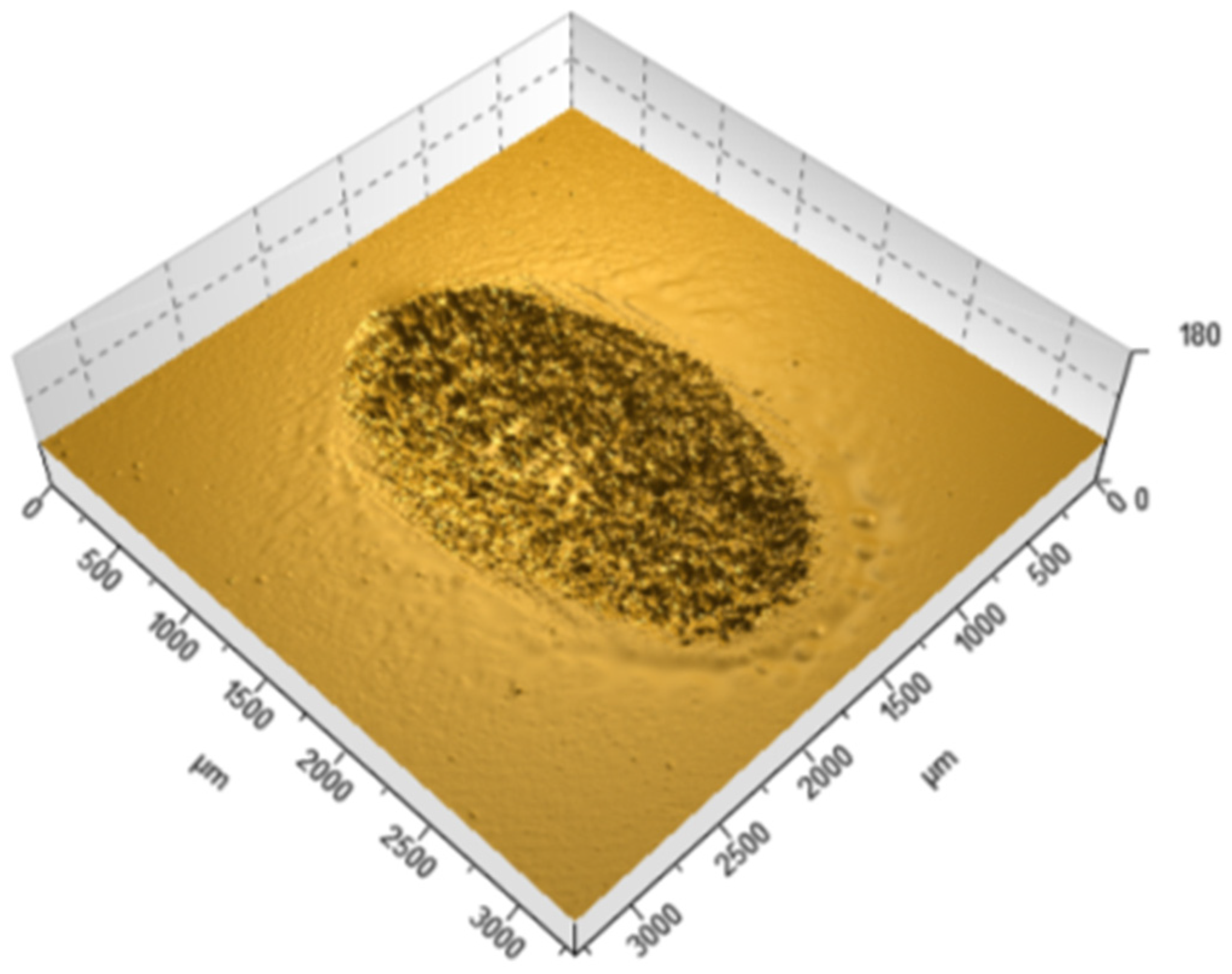

- Wear resistance strongly depends on the composition and microstructure of the material. The resin with the highest inorganic filler content (VST, 30–50 wt%) demonstrated the lowest volumetric wear, the shallowest scratch depth, and the most stable surface structure. In contrast, Gr-17 and Gr-17.1, which contain significantly lower filler content, exhibited higher surface degradation and reduced mechanical stability.

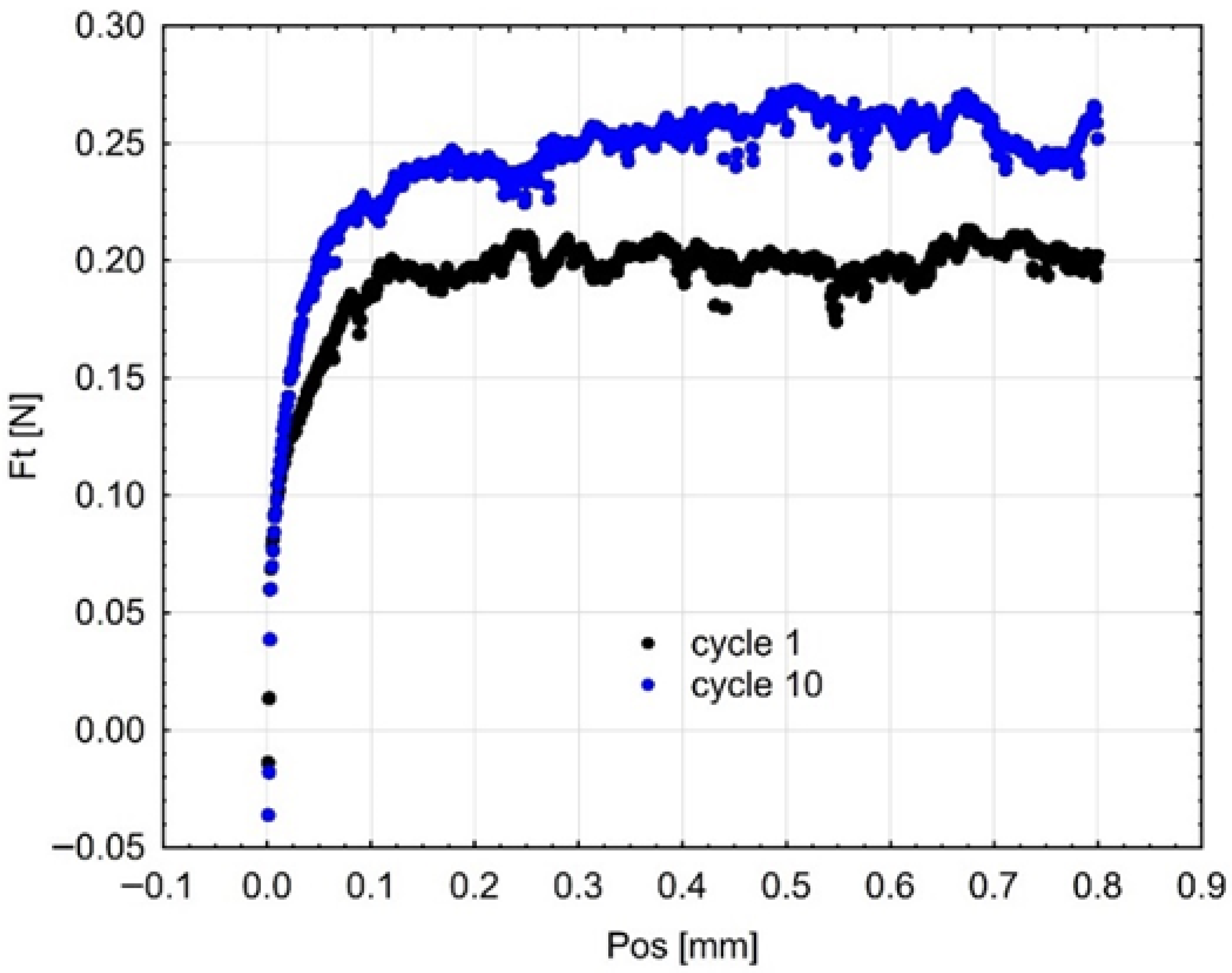

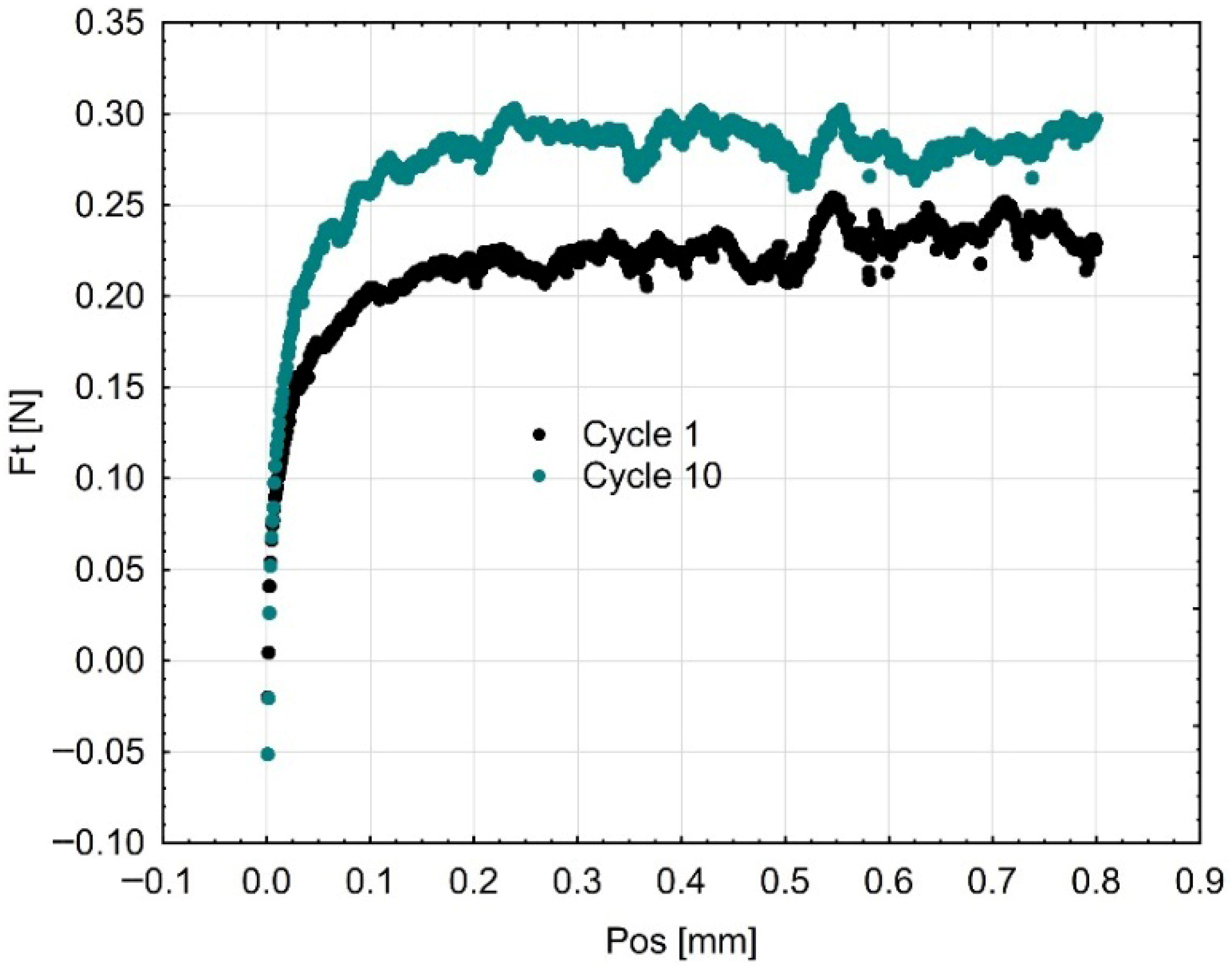

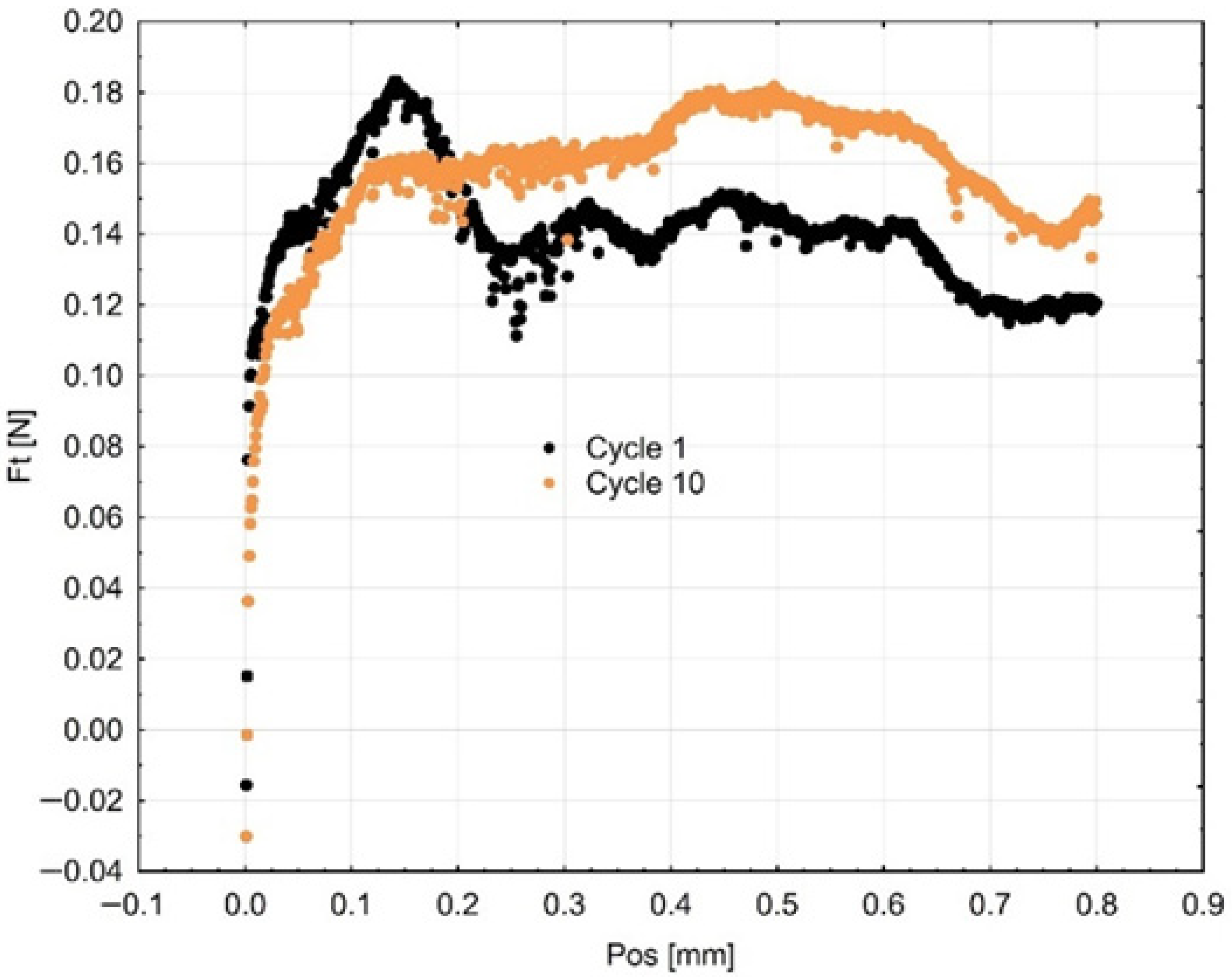

- The coefficient of friction does not correlate directly with wear intensity. Despite the highest stabilized friction coefficient (~0.8), VST showed the lowest wear, whereas Gr-17.1, with a considerably lower friction coefficient (~0.3), experienced greater material loss. This indicates that microstructural reinforcement and filler–matrix interactions play a more decisive role in wear resistance than friction alone.

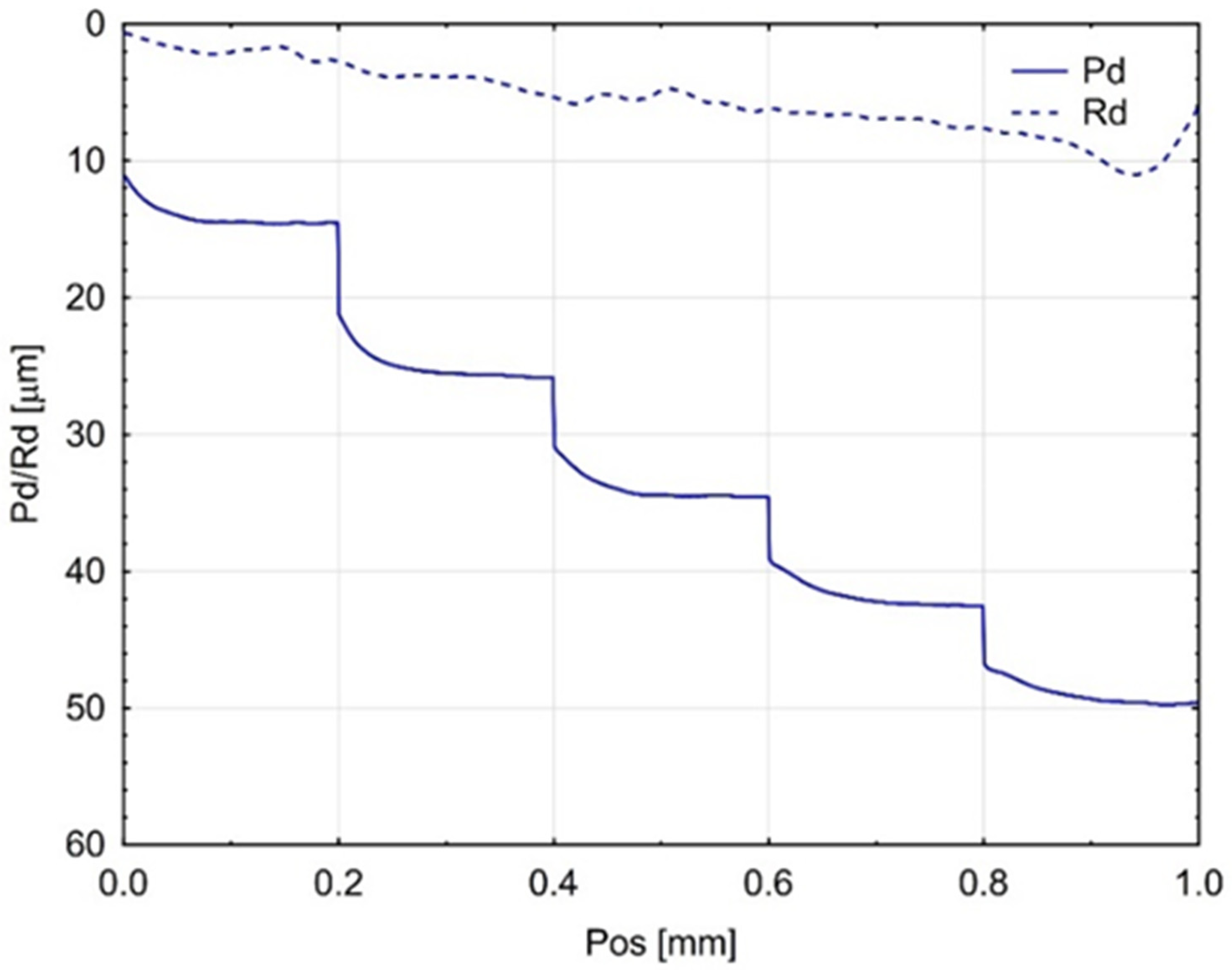

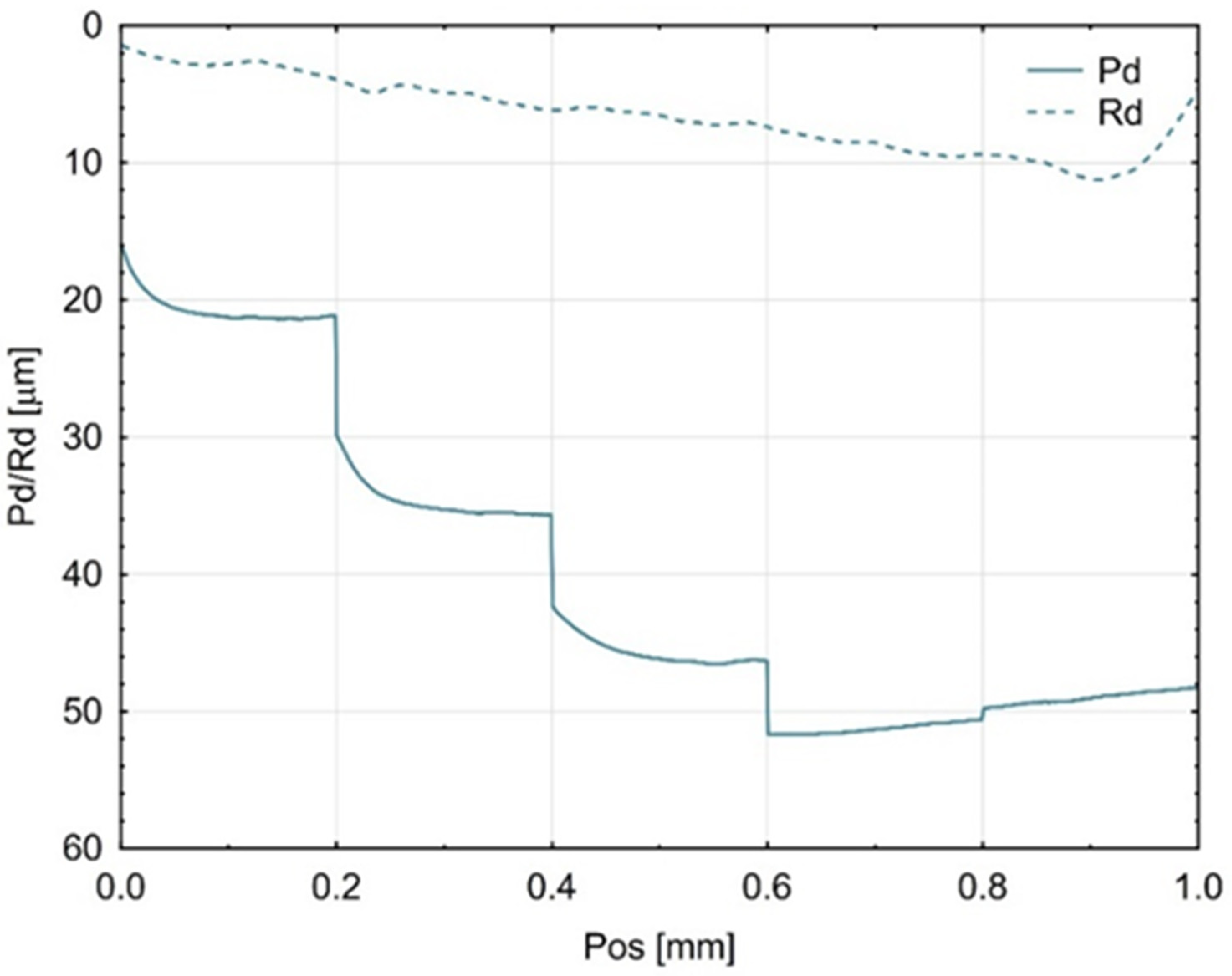

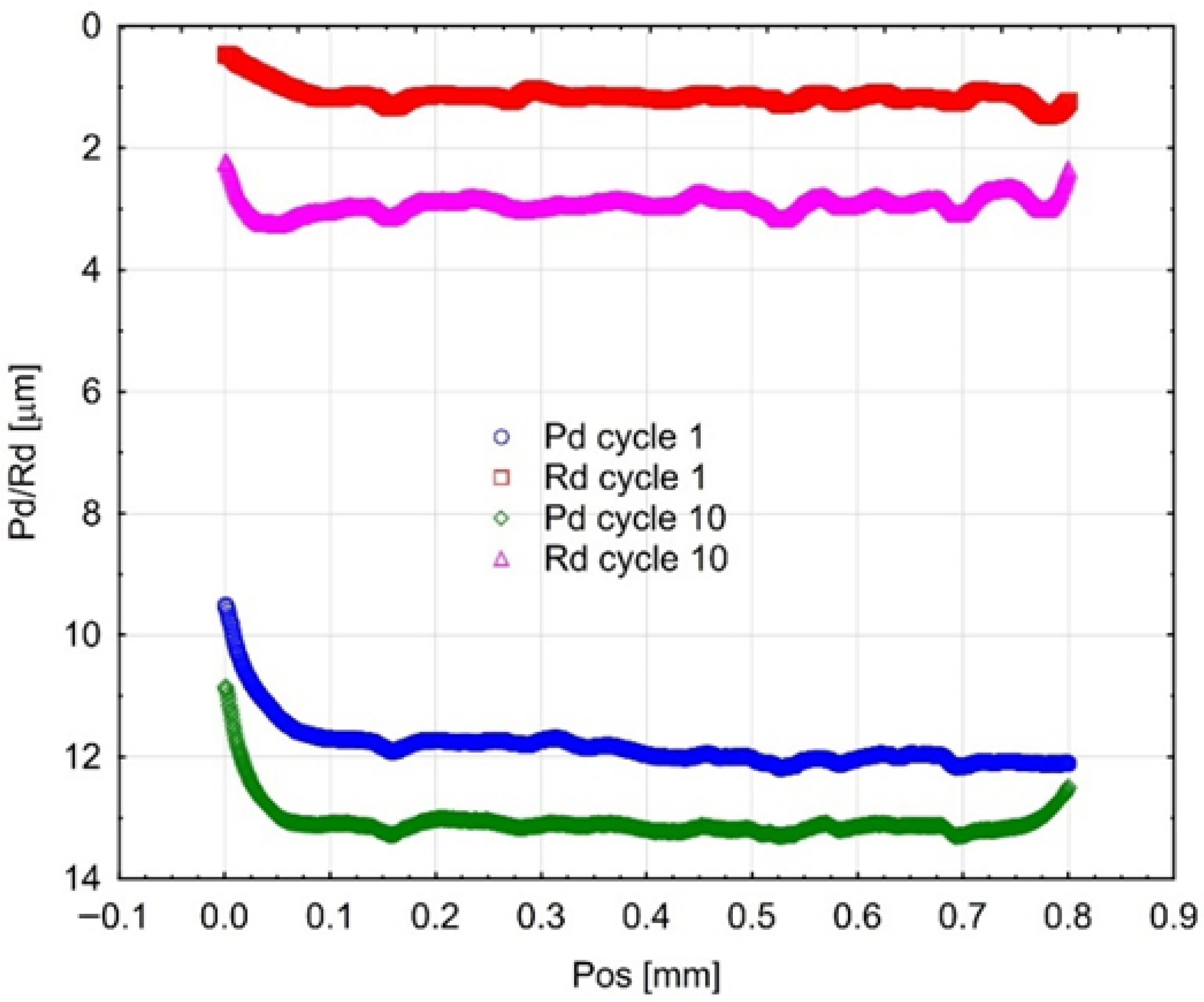

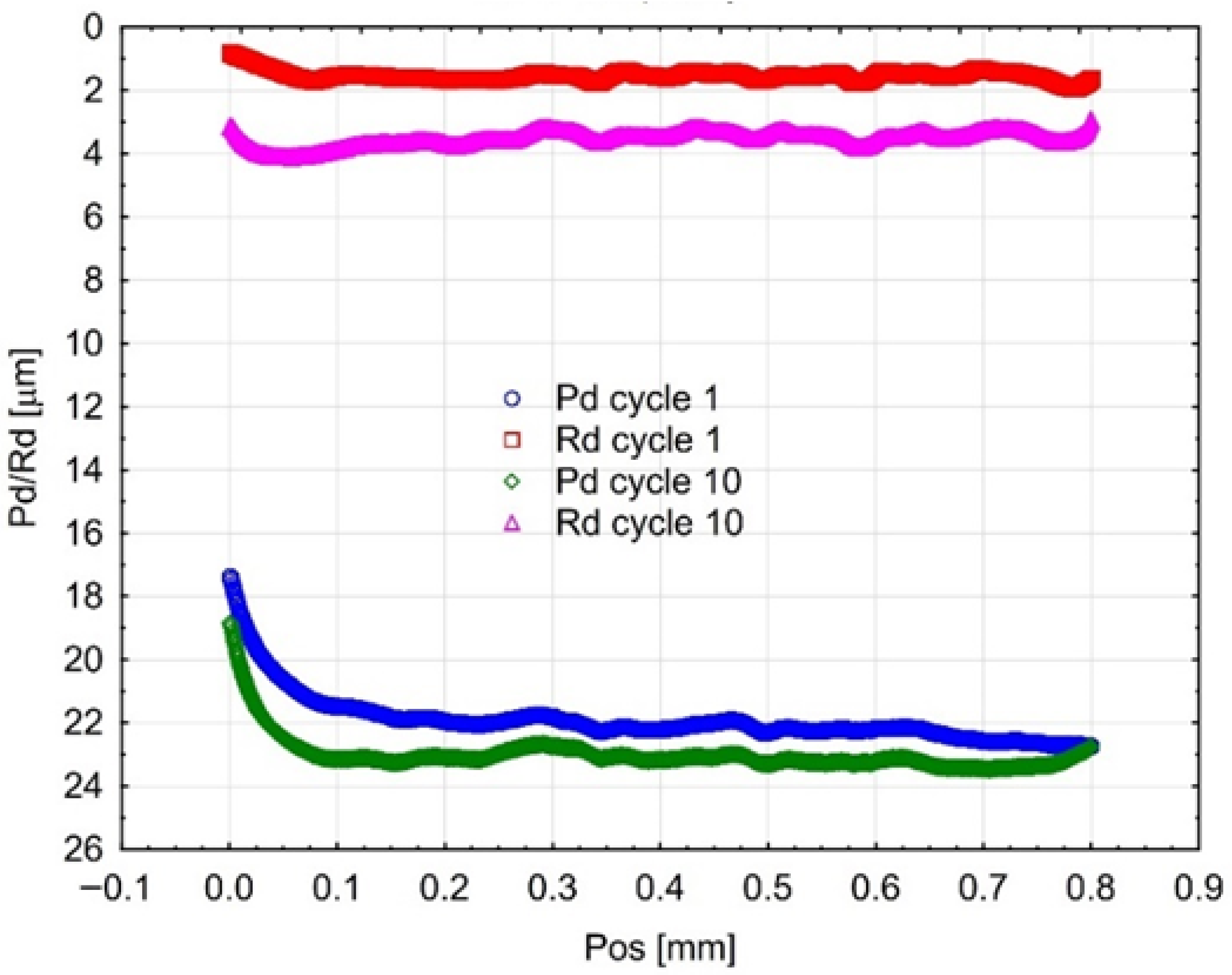

- Scratch resistance is closely linked to filler distribution and elastic recovery. VST showed the greatest resistance to plastic deformation under both incremental and cyclic scratch loading, confirming its superior surface elasticity and reinforcing the importance of filler-based strengthening in temporary crown materials.

- Tribological evaluation under physiological conditions is essential for predicting clinical performance. Testing in a humid environment at 37 °C and under cyclic loading provides relevant insight into the behavior of temporary crowns during mastication and supports the suitability of such methods for preclinical assessment.

- Material optimization based on preclinical testing can significantly improve the durability and dimensional stability of temporary restorations. Selecting materials with enhanced filler content and more homogeneous microstructures may help maintain occlusal integrity and functional properties throughout the intended treatment period.

- Future studies should incorporate advanced microstructural characterization techniques (e.g., EDS, µCT, high-resolution interface analysis) to further investigate the role of filler–matrix interactions in wear behavior. The development of novel photopolymer resins with increased and diversified filler phases, as well as optimization of DLP printing parameters such as layer thickness, build orientation, and exposure settings, could contribute to further improvements in tribological and mechanical performance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AM | Additive Manufacturing |

| BEGO | BEGO GmbH (manufacturer of VarseoSmile Temp) |

| C&B | Crown and Bridge |

| CoF | Coefficient of Friction |

| DLP | Digital Light Processing |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| MST | Micro Scratch Tester |

| Pd | Penetration Depth |

| Rd | Residual Scratch Depth |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| ShD | Shore D Hardness |

| SRV | Schwingung Reibung Verschleiß (Oscillating Friction and Wear tester) |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| VST | VarseoSmile Temp |

| WLI | White Light Interferometry |

References

- Burke, F.T.; Murray, M.C.; Shortall, A.C. Trends in Indirect Dentistry: 6. Provisional Restorations, More than Just a Temporary. Dent. Update 2005, 32, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, J.; Wassell, R. Provisional Restorations (Part 2). Br. Dent. J. 2023, 235, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piedra-Cascón, W.; Krishnamurthy, V.R.; Att, W.; Revilla-León, M. 3D Printing Parameters, Supporting Structures, Slicing, and Post-Processing Procedures of Vat-Polymerization Additive Manufacturing Technologies: A Narrative Review. J. Dent. 2021, 109, 103630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO/ASTM 52927:2024; Additive Manufacturing—General Principles—Main Characteristics and Corresponding Test Methods. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/81802.html (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Bagheri, A.; Jin, J. Photopolymerization in 3D Printing. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2019, 1, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, L.H.; Stolarski, T.A.; Vowles, R.W.; Lloyd, C.H. Wear: Mechanisms, Manifestations and Measurement. Report of a Workshop. J. Dent. 1996, 24, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesil, Z.D.; Alapati, S.; Johnston, W.; Seghi, R.R. Evaluation of the Wear Resistance of New Nanocomposite Resin Restorative Materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2008, 99, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mair, L.H. Wear in the Mouth the Tribological Dimension; Martin Dunitz Ltd.: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Nie, C.; Gong, P.; Yang, J.; Hu, Z.; Li, B.; Ma, M. Research Progress on the Wear Resistance of Key Components in Agricultural Machinery. Materials 2023, 16, 7646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, G.; Lambrechts, P.; Braem, M.; Vanherle, G. Three-Year Follow-Up of Five Posterior Composites: In Vivo Wear. J. Dent. 1993, 21, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayworm, C.D.; Camargo, S.S.; Bastian, F.L. Influence of Artificial Saliva on Abrasive Wear and Microhardness of Dental Composites Filled with Nanoparticles. J. Dent. 2008, 36, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehl, C.; Scheibner, S.; Ludwig, K.; Kern, M. Wear of Composite Resin Veneering Materials and Enamel in a Chewing Simulator. Dent. Mater. 2007, 23, 1382–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caban, J.; Szala, M.; Kęsik, J.; Czuba, Ł. Wykorzystanie druku 3D w zastosowaniach automotive. Autobusy Tech. Eksploat. Syst. Transp. 2017, 18, 573–579. [Google Scholar]

- Miłek, T.; Orynycz, O.; Matijošius, J.; Tucki, K.; Kulesza, E.; Kozłowski, E.; Wasiak, A. Research on Energy Management in Forward Extrusion Processes Based on Experiment and Finite Element Method Application. Materials 2025, 18, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świć, A.; Gola, A.; Sobaszek, Ł.; Orynycz, O. Control of Machining of Axisymmetric Low-Rigidity Parts. Materials 2020, 13, 5053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, G.M. Tribology of Reciprocating Engines. Tribol. Int. 1983, 16, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grymak, A.; Aarts, J.M.; Cameron, A.B.; Choi, J.J.E. Evaluation of Wear Resistance and Surface Properties of Additively Manufactured Restorative Dental Materials. J. Dent. 2024, 147, 105120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwase, K.; Harunari, Y.; Teramoto, M.; Mori, K. Crystal Structure, Microstructure, and Mechanical Properties of Heat-Treated Oyster Shells. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2023, 147, 106107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.L. Contact Mechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1985; ISBN 978-0-521-34796-9. [Google Scholar]

- Doumit, M.; Beuer, F.; Böse, M.W.H.; Unkovskiy, A.; Hey, J.; Prause, E. Wear Behavior of 3D Printed, Minimally Invasive Restorations: Clinical Data after 24 Months in Function. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025, 134, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heintze, S.D. How to Qualify and Validate Wear Simulation Devices and Methods. Dent. Mater. Off. Publ. Acad. Dent. Mater. 2006, 22, 712–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T.D.; Kashani, A.; Imbalzano, G.; Nguyen, K.T.Q.; Hui, D. Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing): A Review of Materials, Methods, Applications and Challenges. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 143, 172–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tan, C.; Li, L. Review of 3D Printable Hydrogels and Constructs. Mater. Des. 2018, 159, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, A.M.E.; Lahowetz, M.; Egan, P.F. Simulated Tissue Growth in Tetragonal Lattices with Mechanical Stiffness Tuned for Bone Tissue Engineering. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 138, 104913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Ko, K.-H.; Park, C.-J.; Cho, L.-R.; Huh, Y.-H. Connector Design Effects on the in Vitro Fracture Resistance of 3-Unit Monolithic Prostheses Produced from 4 CAD-CAM Materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 1319.e1–1319.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansbury, J.W.; Idacavage, M.J. 3D Printing with Polymers: Challenges among Expanding Options and Opportunities. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Gu, H.; Jang, M.; Bayarsaikhan, E.; Lim, J.-H.; Shim, J.-S.; Lee, K.-W.; Kim, J.-E. Influence of Postwashing Process on the Elution of Residual Monomers, Degree of Conversion, and Mechanical Properties of a 3D Printed Crown and Bridge Materials. Dent. Mater. 2022, 38, 1812–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, A.; Reymus, M.; Hickel, R.; Kunzelmann, K.-H. Three-Body Wear of 3D Printed Temporary Materials. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, 1805–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniappan, S.; Celis, J.-P.; Van Meerbeek, B.; Peumans, M.; Lambrechts, P. Correlating in Vitro Scratch Test with in Vivo Contact Free Occlusal Area Wear of Contemporary Dental Composites. Dent. Mater. Off. Publ. Acad. Dent. Mater. 2013, 29, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myagmar, G.; Lee, J.-H.; Ahn, J.-S.; Yeo, I.-S.L.; Yoon, H.-I.; Han, J.-S. Wear of 3D Printed and CAD/CAM Milled Interim Resin Materials after Chewing Simulation. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2021, 13, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, G.S.; Bandyopadhyay, K.; Sahai, K. Keeping in Pace with the New Biomedical Waste Management Rules: What We Need to Know! Med. J. Armed Forces India 2019, 75, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y. Design and Experimental Investigation of a Novel Compliant Positioning Stage with Low-Frequency Vibration Isolation Capability. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2019, 295, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza-e-Silva, C.M.; Da Silva Ventura, T.M.; De Pau, L.; Cassiano, L.S.; De Lima Leite, A.; Buzalaf, M.A.R. Effect of Gels Containing Chlorhexidine or Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate on the Protein Composition of the Acquired Enamel Pellicle. Arch. Oral Biol. 2017, 82, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, J.; Costa, J.F.; Carvalho, C.N.; Grande, R.H.M.; Loguercio, A.D.; Reis, A. Characterization of Two Ni–Cr Dental Alloys and the Influence of Casting Mode on Mechanical Properties. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2012, 56, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkan, A.; Bulut, E.; Arici, S.; Sato, S. Evaluation of Treatments in Patients with Nocturnal Bruxism on Bite Force and Occlusal Contact Area: A Preliminary Report. Eur. J. Dent. 2008, 2, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mair, L.H. Wear in Dentistry—Current Terminology. J. Dent. 1992, 20, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 178:2019; Plastics—Determination of Flexural Properties. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/70513.html (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- ISO 4049:2019; Dentistry—Polymer-Based Restorative Materials. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/67596.html (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- ISO 48-4:2018; Rubber, Vulcanized or Thermoplastic—Determination of Hardness Part 4: Indentation Hardness by Durometer Method (Shore Hardness). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/74969.html (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Printodent® GR-17.1 Temporary It|A1|1 Kg|D1001441. Available online: https://www.pro3dure.com/en/printodent-gr-17.1-temporary-it/D1001441 (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- VarseoSmile® Temp—The Tooth-Colored Resin for 3D. Available online: https://www.bego.com/3d-printing/materials/varseosmile-temp/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- ISO 25178-2:2021; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Surface Texture: Area. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/74591.html (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Shin, Y.; Wada, K.; Tsuchida, Y.; Ijbara, M.; Ikeda, M.; Takahashi, H.; Iwamoto, T. Wear Behavior of Materials for Additive Manufacturing after Simulated Occlusion of Deciduous Dentition. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2023, 138, 105627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.R.; Zheng, J. Tribology of Dental Materials: A Review. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 2008, 41, 113001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, E.F.; Nima, G.; Rueggeberg, F.A.; Giannini, M. Effect of Build Orientation in Accuracy, Flexural Modulus, Flexural Strength, and Microhardness of 3D-Printed Resins for Provisional Restorations. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 136, 105479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prause, E.; Hey, J.; Beuer, F.; Schmidt, F. Wear Resistance of 3D-Printed Materials: A Systematic Review. Dent. Rev. 2022, 2, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.E.; Morton, D.G. The Mouth, Salivary Glands and Oesophagus. In The Digestive System; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 19–38. ISBN 978-0-7020-3367-4. [Google Scholar]

- Snarski-Adamski, A.; Pieniak, D.; Krzysiak, Z.; Firlej, M.; Brumerčík, F. Evaluation of the Tribological Behavior of Materials Used for the Production of Orthodontic Devices in 3D DLP Printing Technology, Due to Oral Cavity Environmental Factors. Materials 2025, 18, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrilho, M.R.D.O.; Tay, F.R.; Pashley, D.H.; Tjäderhane, L.; Marins Carvalho, R. Mechanical Stability of Resin–Dentin Bond Components. Dent. Mater. 2005, 21, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieniak, D.; Michalczewski, R.; Firlej, M.; Krzysiak, Z.; Przystupa, K.; Kalbarczyk, M.; Osuch-Słomka, E.; Snarski-Adamski, A.; Gil, L.; Seykorova, M. Surface Layer Performance of Low-Cost 3D-Printed Sliding Components in Metal-Polymer Friction. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2024, 30, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesne, A. Surface Tension and the Origin of the Circular Hydraulic Jump in a Thin Liquid Film. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2019, 4, 084001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafran, M.; Cwalińska, A.; Jałbrzykowski, M. Wpływ dodatku nowych rozgałęzionych żywic uretanowo-metakrylowych na właściwości mechaniczne i tribologiczne kompozytów ceramiczno-polimerowych do zastosowań stomatologicznych. Kompozyty 2008, 8, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, N.; Hahnel, S.; Dowling, A.H.; Fleming, G.J.P. The in vitro wear behavior of experimental resin-based composites derived from a commercial formulation. Dent. Mater. 2013, 29, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Bao, S.; Liu, F.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, B.; Zhu, M. Wear behavior of light-cured resin composites with bimodal silica nanostructures as fillers. Mater. Sci. Eng. C-Mater. Biol. Appl. 2012, 33, 4759–4766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turssi, C.P.; De Moraes Purquerio, B.; Serra, M.C. Wear of dental resin composites: Insights into underlying processes and assessment methods—A review. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B 2003, 65, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieniak, D.; Walczak, A.; Niewczas, A.M. Comparative study of wear resistance of the composite with microhybrid structure and nanocomposite. Acta Mech. Autom. 2016, 10, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieniak, D.; Przystupa, K.; Walczak, A.; Niewczas, A.M.; Krzyzak, A.; Bartnik, G.; Gil, L.; Lonkwic, P. Hydro-Thermal Fatigue of Polymer Matrix Composite Biomaterials. Materials 2019, 12, 3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayne, S.C. Correlation of clinical performance with “in vitro tests” of restorative dental materials that use polymer-based matrices. Dent. Mater. 2012, 28, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Rouf, S.; Ul Haq, M.I.; Raina, A.; Valerga Puerta, A.P.; Sagbas, B.; Ruggiero, A. Tribo-Corrosive Behavior of Additive Manufactured Parts for Orthopaedic Applications. J. Orthop. 2022, 34, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.R. Friction and Wear Mechanism of Polymers, Their Composites and Nanocomposites. In Tribology of Polymers, Polymer Composites, and Polymer Nanocomposites; George, S.C., Haponiuk, J.T., Thomas, S., Reghunath, R., Sarath, P.S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 51–117. ISBN 978-0-323-90748-4. [Google Scholar]

- Longela, S.; Chatzitakis, A. In Vitro Corrosion Behaviour of Phenolic Coated Nickel-Titanium Surfaces. Biosurf. Biotribol. 2017, 6, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condon, J.R.; Ferracane, J.L. In Vitro Wear of Composite with Varied Cure, Filler Level, and Filler Treatment. J. Dent. Res. 1997, 76, 1405–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Kim, Y.-C.; Cho, J.-E.; Yim, C.-H.; Yun, D.-S.; Lee, T.-G.; Park, N.-K.; Chung, R.-H.; Hong, D.-G. Microstructural Evolution, Hardness and Wear Resistance of WC-Co-Ni Composite Coatings Fabricated by Laser Cladding. Materials 2024, 17, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baiocco, G.; Genna, S.; Salvi, D.; Ucciardello, N. Laser Texturing to Increase the Wear Resistance of an Electrophoretic Graphene Coating on Copper Substrates. Materials 2023, 16, 5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Xin, L.; Yu, Z.; Zhu, Z. Construction of a Dynamic Model for the Interaction between the Versatile Tracks and a Vehicle. Eng. Struct. 2020, 206, 110067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, J.G.; Ortega, J.; Coffey, E.; Hannigan, M. Low-Cost Measurement Techniques to Characterize the Influence of Home Heating Fuel on Carbon Monoxide in Navajo Homes. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 625, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Cho, W.; Lee, H.; Bae, J.; Jeong, T.; Huh, J.; Shin, J. Strength and Surface Characteristics of 3D-Printed Resin Crowns for the Primary Molars. Polymers 2023, 15, 4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Gr-17.1 Temporary It (Abbrev. Gr-17.1) | Gr-17 Temporary (Abbrev. Gr-17) | VarseoSmile Temp (Abbrev. VST) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Pro3dure | Pro3dure | BEGO |

| 3D printer and parameters | ASIGA UV MAX (wavelength 385 nm, 1919 dpi × 1081 dpi, 62 µm) | ASIGA UV MAX (wavelength 385 nm, 1919 dpi × 1081 dpi, 62 µm) | ASIGA UV MAX (wavelength 385 nm, 1919 dpi × 1081 dpi, 62 µm) |

| Manufacturer’s description (intended use) | Biocompatible material for temporary crowns and bridges; long-term dental restorations (anterior and posterior region), prosthetic teeth. | Biocompatible material for temporary crowns and bridges used in the anterior region. | Biocompatible material for temporary crowns and bridges; prosthetic restorations for anterior and posterior regions. |

| Resin | 7,7,9(or 7,9,9)-trimethyl-4,13-dioxo-3,14-dioxa-5,12-diazahexadecane-1,16-diyl bismethacrylate, | 7,7,9(or 7,9,9)-trimethyl-4,13-dioxo-3,14-dioxa-5,12-diazahexadecane-1,16-diyl bismethacrylate, | “4,4′-isopropylidiphenol, ethoxylated, and 2-methylprop-2-enoic acid; silanized dental glass; methyl benzoylformate; diphenyl (2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phosphine oxide.” |

| 3,6,9-trioxaundecamethylene Dimethacrylate, | 3,6,9-trioxaundecamethylene Dimethacrylate, | ||

| Phenyl bis(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)-phosphine oxide | Phenyl bis(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)-phosphine oxide | ||

| Filler | Contain inorganic fillers with a particle size in the range of 0.4–3 μm, filler content of ~40.0 m-%. | Contain inorganic fillers with a particle size in the range of 0.4–3 μm, filler content of ~20.0 m-%. | Silanized glass-ceramic filler with a declared content of approximately 30–50 wt% (average particle size ~ 0.7 μm). |

| Elastic modulus | 5528 MPa [37] | 2442 MPa [37] | ≥3500 MPa |

| Flexural strength | 169 MPa [38] | 113 MPa [37] | ≥100 MPa |

| Shore D hardness | 80 ShD [39,40] | 80 ShD [39] | ≥90 ShD [41] |

| Materials | Gr-17.1 Temporary It | Gr-17 Temporary | VarseoSmile Temp |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wear [mm3] | |||

| Sample 1 | 0.190174 | 0.064141 | 0.026421 |

| Sample 2 | 0.262957 | 0.071113 | 0.018415 |

| Sample 3 | 0.251218 | 0.073901 | 0.030516 |

| Mean | 0.234783 | 0.069718 | 0.025117 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Firlej, M.; Pieniak, D.; Snarski-Adamski, A.; Biedziak, B.; Niewczas, A.; Petru, J.; Matijošius, J.; Krzysiak, Z.; Zaborowicz, K. Comparative Study on the Wear Resistance of C&B-Type Polymer Materials for Temporary Crowns Manufactured Using 3D DLP Printing Technology. Materials 2025, 18, 5478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245478

Firlej M, Pieniak D, Snarski-Adamski A, Biedziak B, Niewczas A, Petru J, Matijošius J, Krzysiak Z, Zaborowicz K. Comparative Study on the Wear Resistance of C&B-Type Polymer Materials for Temporary Crowns Manufactured Using 3D DLP Printing Technology. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245478

Chicago/Turabian StyleFirlej, Marcel, Daniel Pieniak, Andrzej Snarski-Adamski, Barbara Biedziak, Agata Niewczas, Jana Petru, Jonas Matijošius, Zbigniew Krzysiak, and Katarzyna Zaborowicz. 2025. "Comparative Study on the Wear Resistance of C&B-Type Polymer Materials for Temporary Crowns Manufactured Using 3D DLP Printing Technology" Materials 18, no. 24: 5478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245478

APA StyleFirlej, M., Pieniak, D., Snarski-Adamski, A., Biedziak, B., Niewczas, A., Petru, J., Matijošius, J., Krzysiak, Z., & Zaborowicz, K. (2025). Comparative Study on the Wear Resistance of C&B-Type Polymer Materials for Temporary Crowns Manufactured Using 3D DLP Printing Technology. Materials, 18(24), 5478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245478