Recent Advances on Aluminum-Based Boron Carbide Composites: Performance, Fabrication, and Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Research Hypotheses

- (2)

- Key Research Questions

- (1)

- Core Academic Contributions Establishment of a multi-scale interface design theoretical system

- (2)

- Differentiating Features from Similar Studies

- (3)

- Publication Value and Academic Significance

2. Material Fabrication

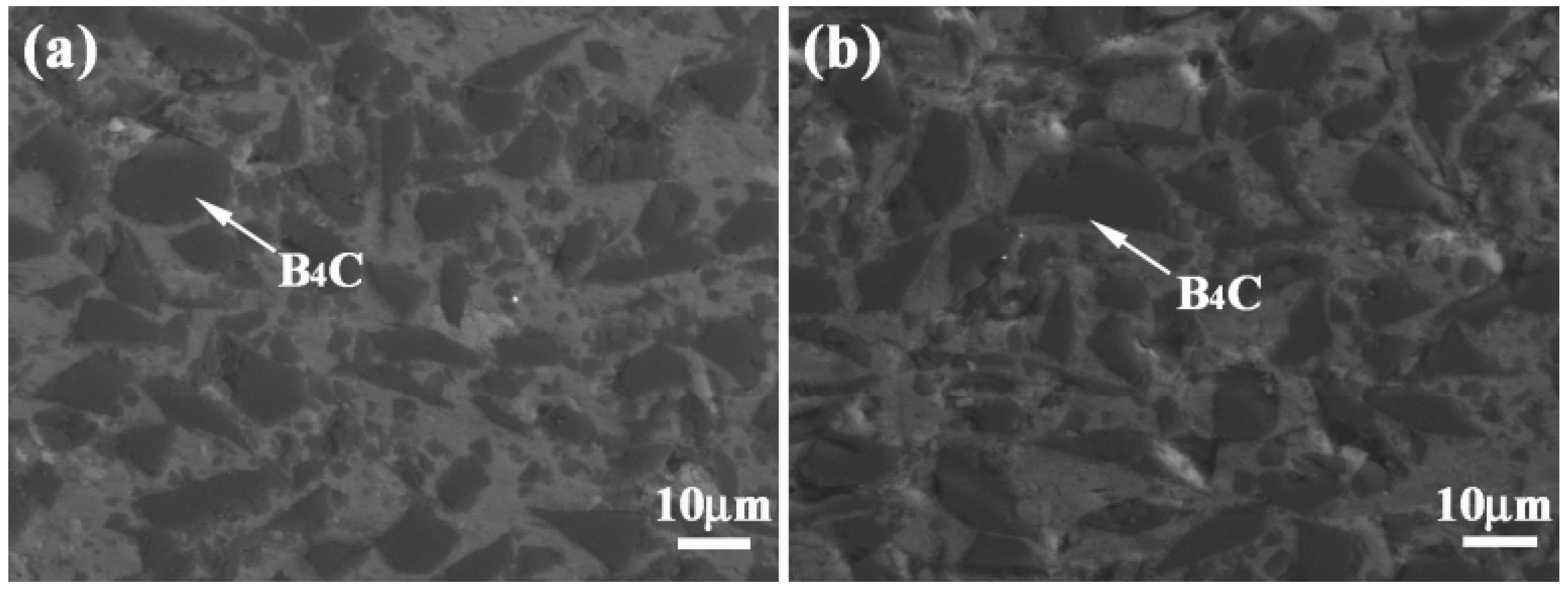

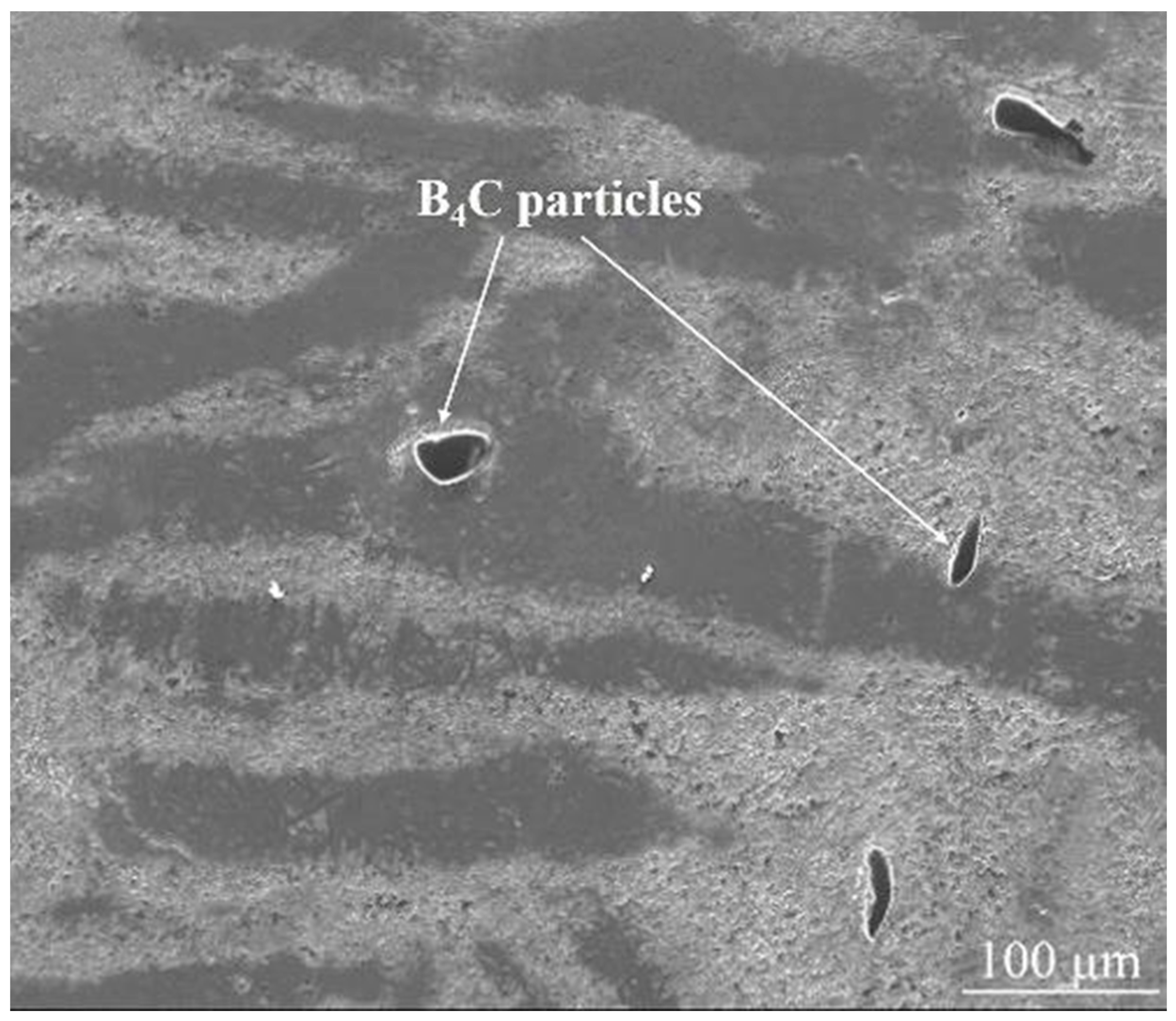

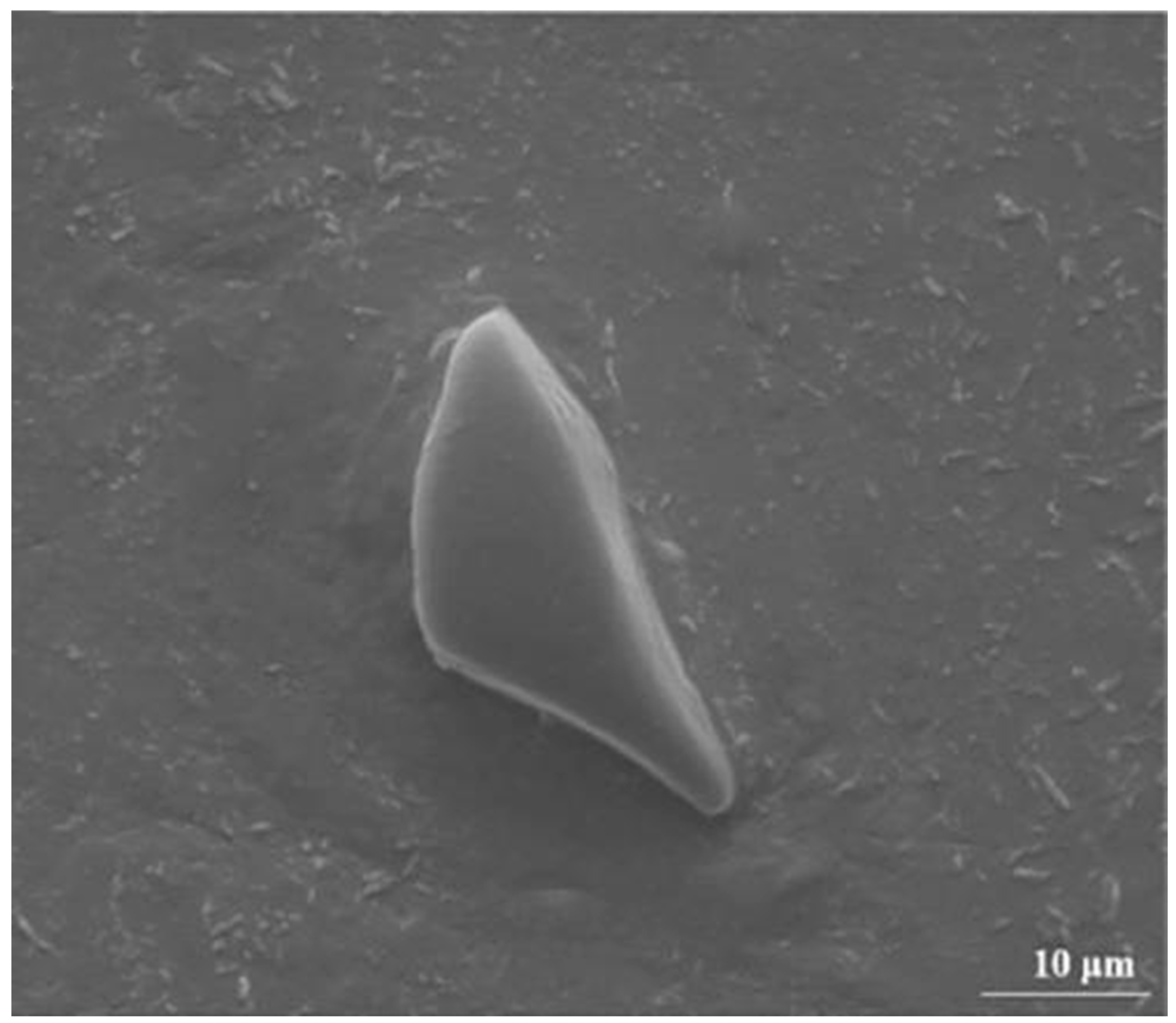

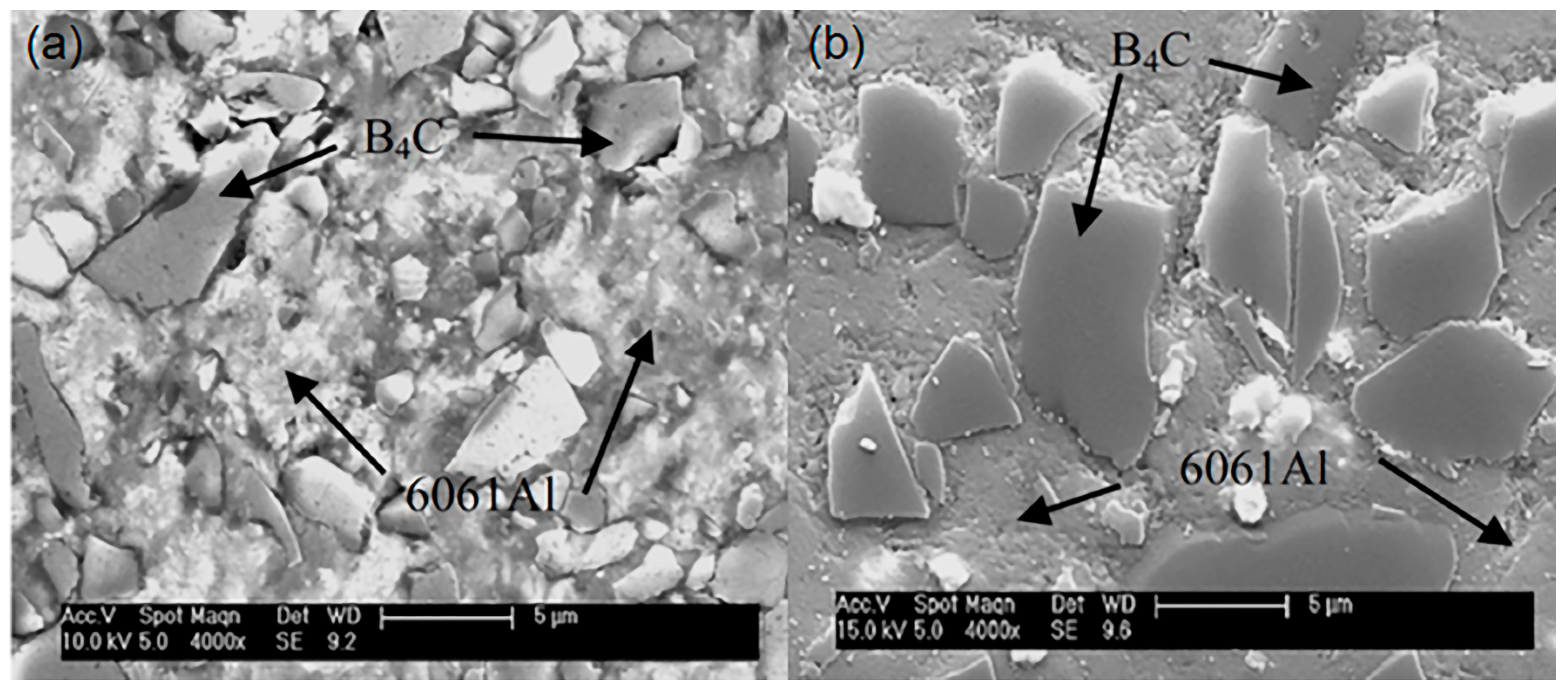

2.1. Powder Metallurgy Method

2.2. Liquid Preparation Technology

2.3. Solid-State Processing Technology

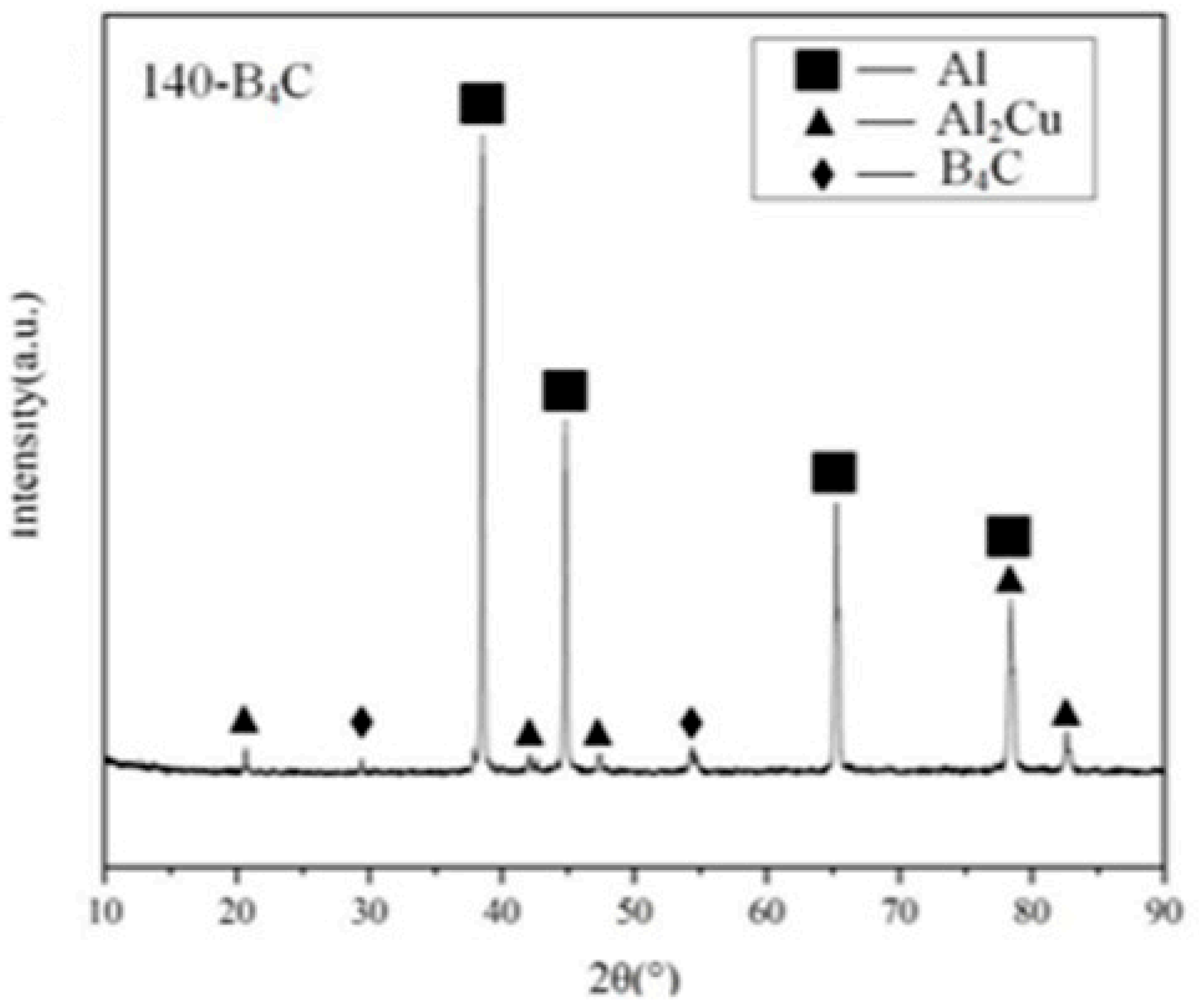

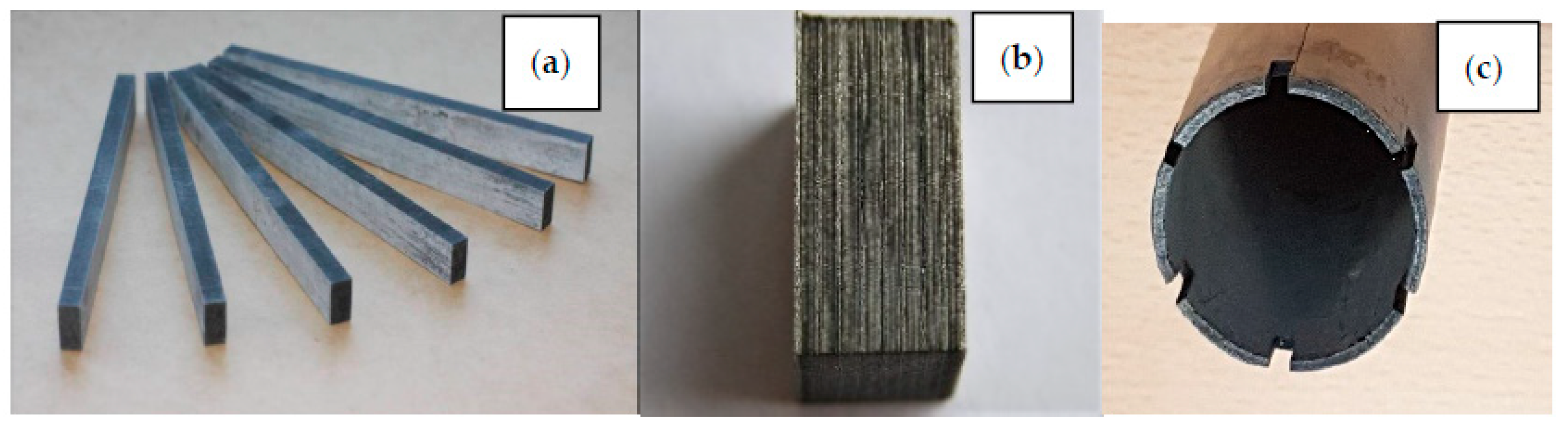

2.4. Additive Manufacturing (AM) Technology

2.5. Surface Composite Technology

2.6. Cost and Sustainability Analysis of Primary Fabrication Processes

2.6.1. Quantitative Cost Comparison Between AM and ECAP Processes

2.6.2. Sustainability Assessment of AM and ECAP Processes

2.6.3. Directions for Sustainability Optimization

3. Performance Characteristics

3.1. Mechanical Properties

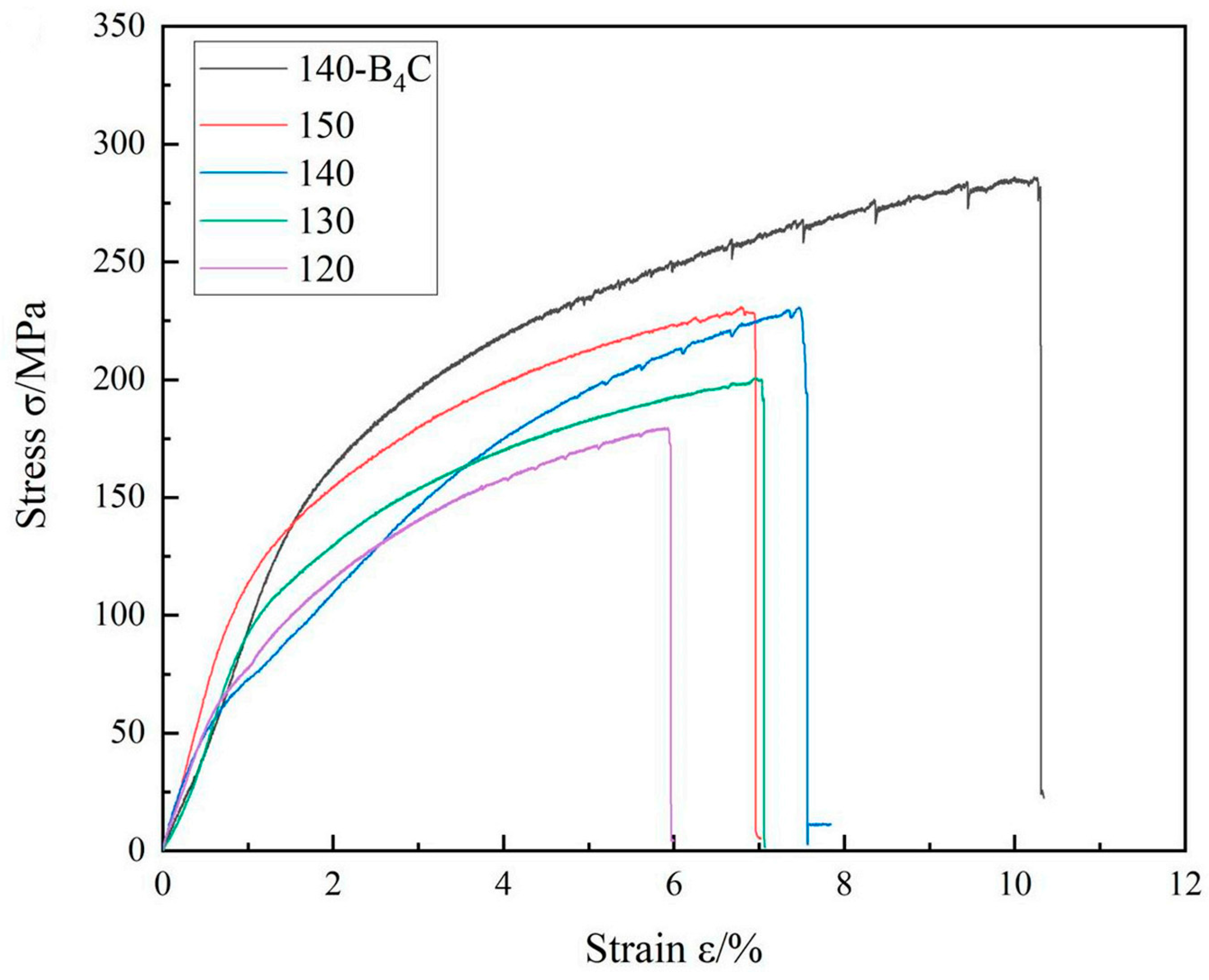

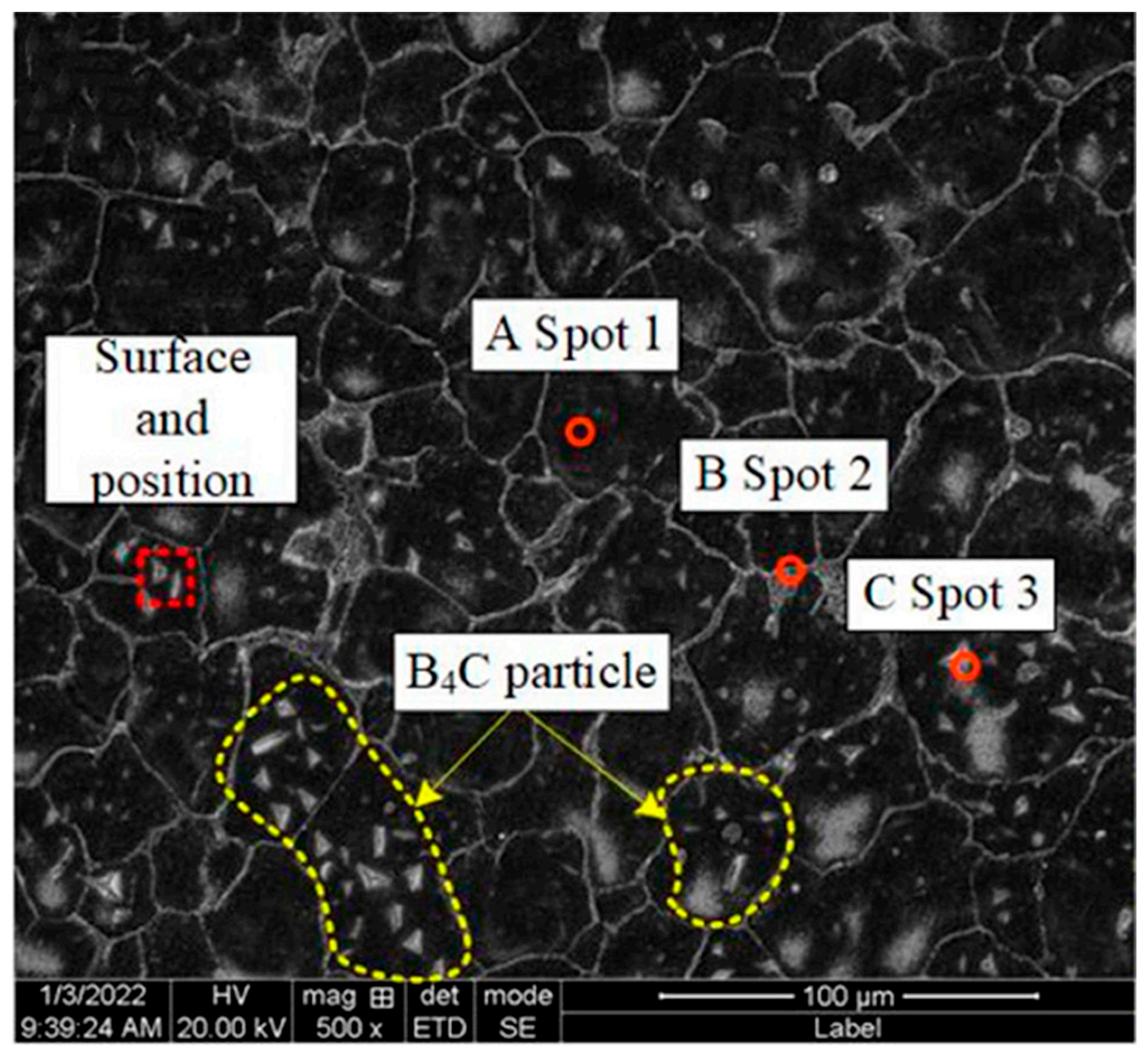

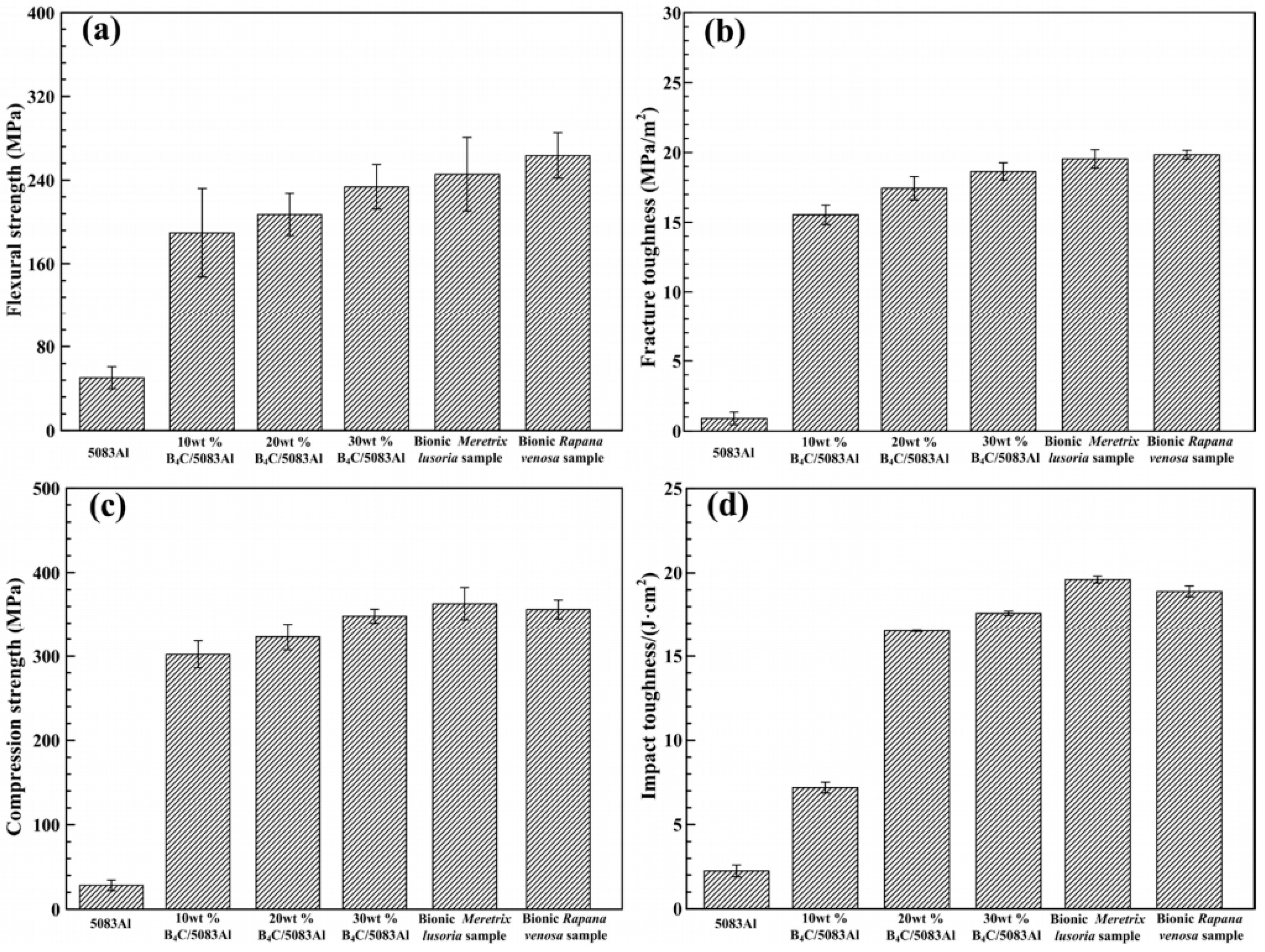

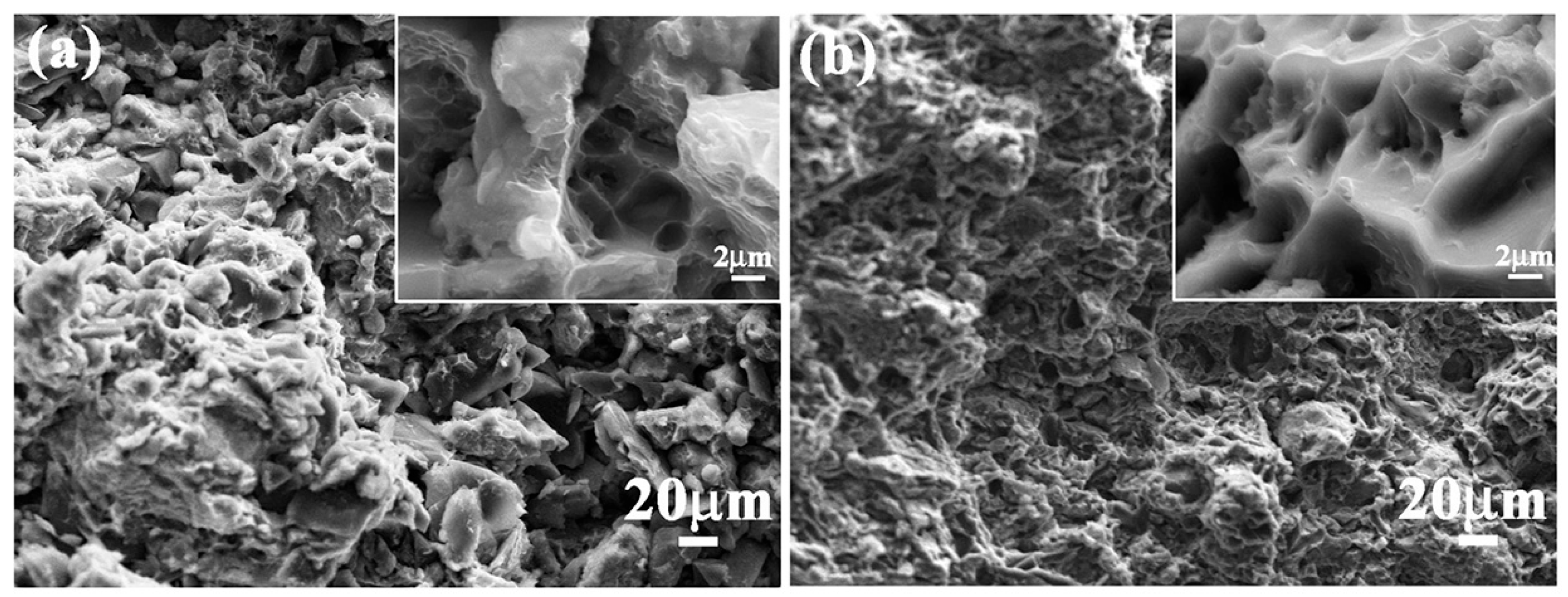

3.1.1. Strength Characteristics

3.1.2. Hardness and Toughness

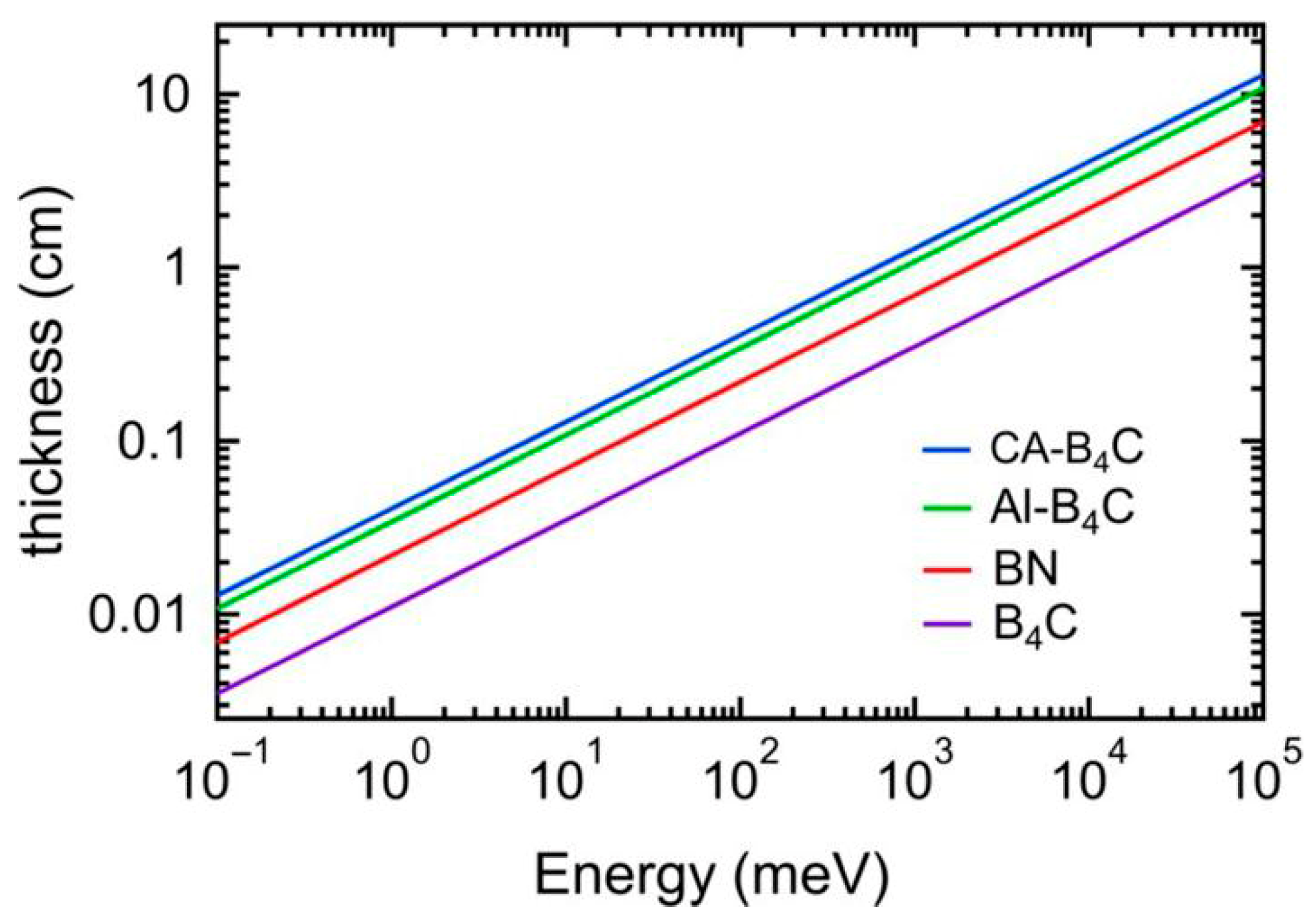

3.2. Shielding Performance

3.2.1. Neutron Absorption Characteristics

3.2.2. Irradiation Stability

3.3. Thermophysical Properties

3.4. Friction and Wear Performance: Wear Mechanisms and Experimental Conditions

3.4.1. Friction and Wear Performance

3.4.2. Analysis of Wear Mechanisms and Experimental Conditions

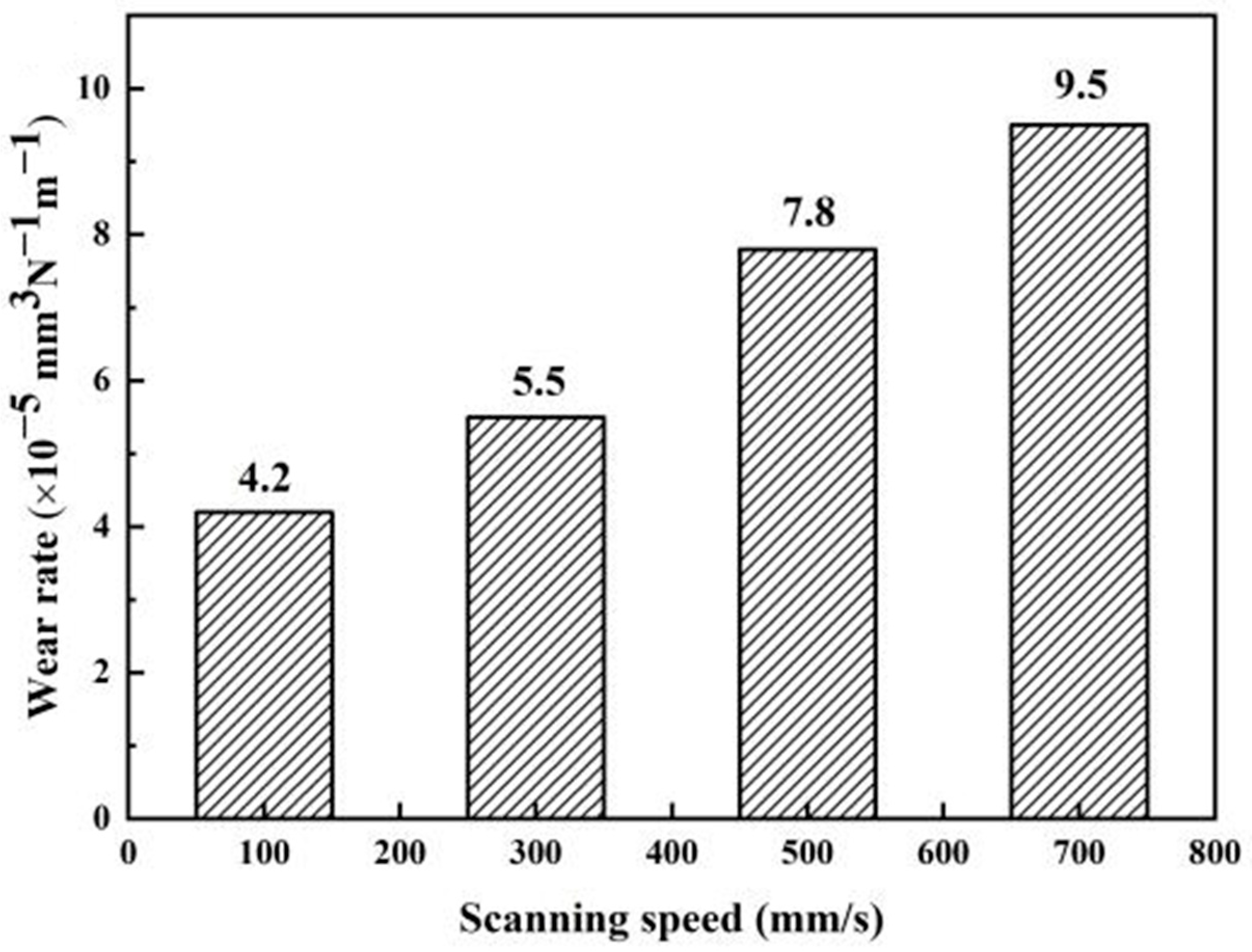

Quantitative Influence of Experimental Conditions on Wear Performance

Dominant Wear Mechanisms in B4C/Al Composites

Strategies for Controlling Wear Mechanisms

3.5. Other Performances

3.5.1. Corrosion Resistance

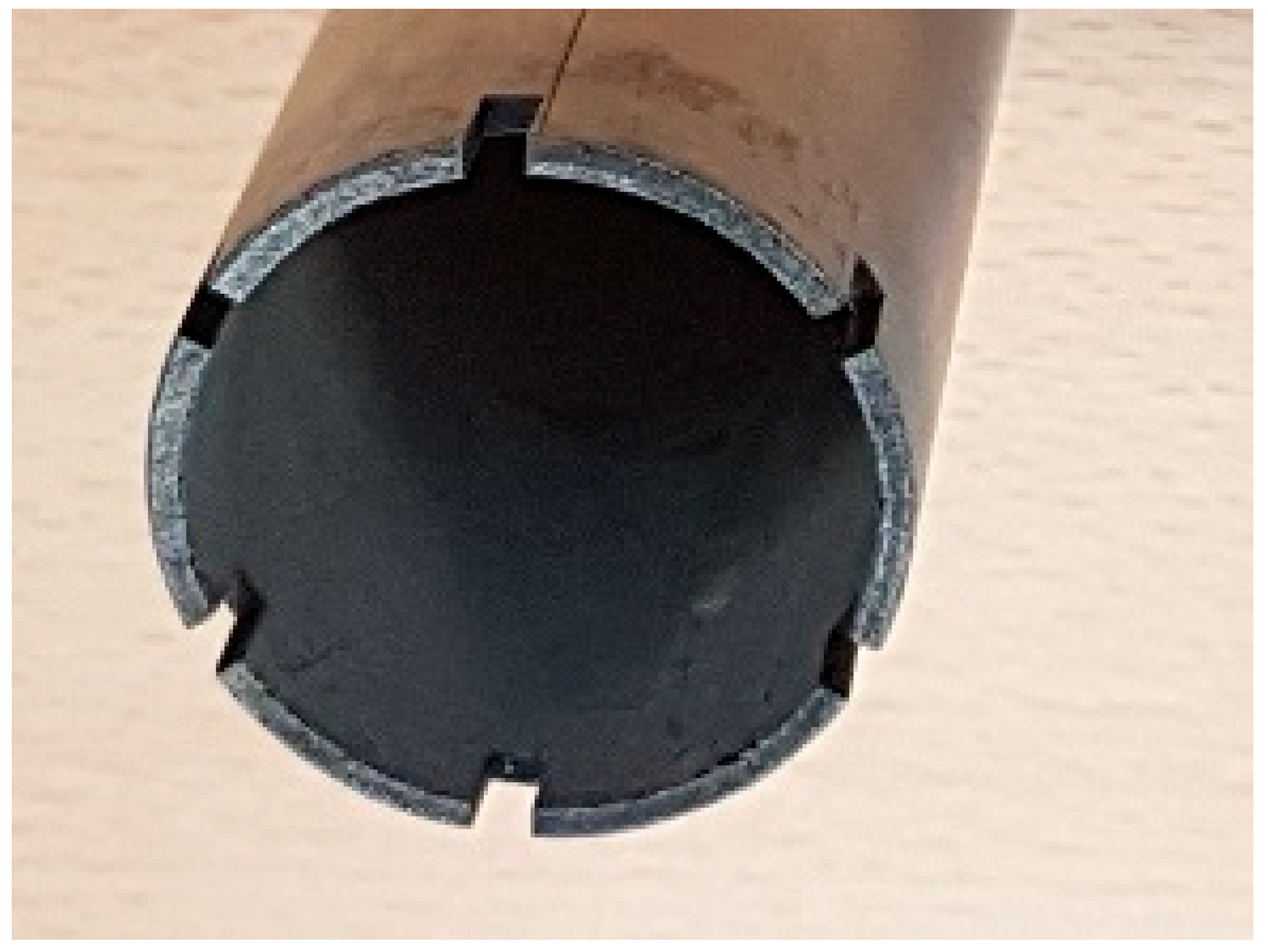

3.5.2. Processing Performance

3.6. Quantitative Analysis of Property-Process Relationships

4. Application Fields

4.1. Nuclear Energy Engineering

4.1.1. Spent Fuel Storage

4.1.2. Reactor Shielding

4.2. National Defense and Military Industry

4.3. Aerospace

4.4. Transportation

4.4.1. Automobile Parts

4.4.2. Rail Transit

4.5. Electronics Industry

4.6. Other Applications

5. Summary and Outlook

5.1. Summary of Research Progress

5.2. Key Issues

5.2.1. Interface Response Control

5.2.2. Process Repeatability

5.2.3. Irradiation Damage Mechanism

5.2.4. Research Gap in Wear Mechanisms

5.3. Future Development Direction

5.3.1. Multi-Scale Interface Design

5.3.2. Intelligent Preparation Process

5.3.3. Prediction of Extreme Environmental Behaviors

5.3.4. Sustainable Development

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shu, S.; Yang, H.; Tong, C.; Qiu, F. Fabrication of TiCx-TiB2/Al Composites for Application as a Heat Sink. Materials 2016, 9, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, S.C.V.R.M.; Vellingiri, S.; Prabhu, P.; Hussain, B.I.; Asary, A.R.; Padmanaban, G.; Srinivasnaik, M.; Yuvaraj, K.P. A Detailed Study on Using Novel LM 25 Aluminium Alloy Hybrid Metal Matrix Nanocomposite for Nuclear Applications. Recent Pat. Nanotechnol. 2025, 19, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajević, S.; Miladinović, S.; Güler, O.; Özkaya, S.; Stojanović, B. Optimization of Dry Sliding Wear in Hot-Pressed Al/B4C Metal Matrix Composites Using Taguchi Method and ANN. Materials 2024, 17, 4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pethuraj, M.; Uthayakumar, M.; Rajesh, S.; Majid, M.S.A.; Rajakarunakaran, S.; Niemczewska-Wójcik, M. Dry Sliding Wear Studies on Sillimanite and B4C Reinforced Aluminium Hybrid Composites Fabricated by Vacuum Assisted Stir Casting Process. Materials 2022, 16, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Wu, C.D.; Luo, G.Q.; Fang, P.; Li, C.Z.; Wang, Y.Y.; Zhang, L.M. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Al-7075/B4C composites fabricated by plasma activated sintering. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 588, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.Z.; Liu, X.Q.; Liu, Z.L.; Ding, D. Shielding property calculation of B4C/Al composites for spent fuel transportation and storge. Acta Phys. Sin. 2013, 62, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubaid, F.; Matli, P.R.; Shakoor, R.A.; Parande, G.; Manakari, V.; Mohamed, A.M.A.; Gupta, M. Using B4C Nanoparticles to Enhance Thermal and Mechanical Response of Aluminum. Materials 2017, 10, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirukkumaran, K.; Mukhopadhyay, C.K. Acoustic emission signals analysis to differentiate the damage mechanism in the drilling of Al-5%B4C metal matrix composite. Ultrasonics 2022, 124, 106762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karabulut, Ş.; Karakoç, H.; Çıtak, R. Influence of B4C particle reinforcement on mechanical and machining properties of Al6061/B4C composites. Compos. Part B-Eng. 2016, 101, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.W.; Chao, Z.L.; Jiang, L.T.; Han, H.M.; Han, B.Z.; Du, S.Q.; Luo, T.; Chen, G.Q.; Mei, Y.; Wu, G.H. Influence of Interface on Mechanical Behavior of Al-B4C/Al Laminated Composites under Quasi-Static and Impact Loading. Materials 2023, 16, 6847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, A.; Su, Y.; Cai, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, K.; Cao, H.; Zhang, D.; Ouyang, Q. Fabrication, microstructure characterization and mechanical properties of B4C microparticles and SiC nanowires hybrid reinforced aluminum matrix composites. Mater. Charact. 2022, 193, 112243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Değirmenci, Ü. Mechanical and tribological behavior of a hybrid WC and Al2O3 reinforced Al–4Gr composite. Mater. Test. 2023, 65, 1416–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubcak, M.; Soltes, J.; Zimina, M.; Weinberger, T.; Enzinger, N. Investigation of Al-B4C Metal Matrix Composites Produced by Friction Stir Additive Processing. Metals 2021, 11, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.A.; Paz y Puente, A.E.; Robinson, A.B.; Glagolenko, I.Y.; Jue, J.F.; Clark, C.R.; Sohn, Y.; Keiser, D.D. Microstructural characterization of as-fabricated monolithic plates with boron carbide, aluminum boride, and zirconium boride burnable absorbers. J. Nucl. Mater. 2022, 559, 153361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.S.; Wang, W.X.; Nie, H.H.; Li, Y.L.; Liu, R.F.; Liu, R.N.; Yang, T. Research Progress and Development of Neutron-absorbing Materials for Nuclear Shielding. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2020, 49, 4358–4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherdyntsev, V.V.; Gorshenkov, M.V.; Kaloshkin, S.D.; Gul’bin, V.N. Metal-matrix radiation-protective composite materials based on aluminum. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 2013, 55, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, C.Z.; Gu, J.J.; Liu, J.L.; Zhang, D. Production of Boron Carbide Reinforced 2024 Aluminum Matrix Composites by Mechanical Alloying. Mater. Trans. 2007, 48, 990–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.K.; Misra, S.S. Experimental characterization and numerical modeling of thermo-mechanical properties of Al-B4C composites. Ceram. Int. 2016, 43, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommana, D.; Rao, C.S.; Kumar, B.N. Effect of 6 wt.% Particle (B4C+SiC) Reinforcement on Mechanical Properties of AA6061 Aluminum Hybrid MMC. Silicon 2022, 14, 4197–4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pul, M.; Ayar, K.B.; Akin, B. Investigation of Mechanical Properties of B4C/SiC Additive Aluminum Based Composites and Modeling of Their Ballistic Performances. J. Polym. Politek. Derg. 2020, 23, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vats, A.; Bharti, S.; Gupta, M. Mechanical and Erosive Wear Analysis of Boron Carbide Reinforced Scrap Aluminium Composites. Int. J. Met. 2025, 19, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambigai, R.; Prabhu, S. Characterization and thermo-mechanical analysis of centrifugally fabricated aluminium-boron carbide functionally graded composites. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part N-J. Nanomater. Nanoeng. Nanosyst. 2024, 238, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, S.; Rao, C.H. A comparative investigation of hardness and compression strength of Nickel coated B4C reinforced 601AC/201AC selective layered functionally graded materials. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 016527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Fan, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Nie, J.; Wei, S. Study on Fabrication and Properties of Graphite/Al Composites by Hot Isostatic Pressing-Rolling Process. Materials 2021, 14, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.H.; Chen, Z.J.; Ren, J.W.; Yang, L.Y.; Li, Y.C.; Wang, Z.; Ning, W.J.; Jia, S.L. Synchronously improved thermal conductivity and dielectric constant for epoxy composites by introducing functionalized silicon carbide nanoparticles and boron nitride microspheres. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 627, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senel, M.C.; Gürbüz, M.; Koç, E. Reciprocating sliding wear properties of sintered Al-B4C composites. Int. J. Miner. Met. Mater. 2022, 29, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhu, B.; Rao, C.S.; Seshu Bai, V. Effect of rubber ash on mechanical properties of Al6061 based hybrid FGMMC. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 096522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.K.; Dixit, A.R.; Tiwari, S. Investigation of micro-structural and mechanical properties of metal matrix composite A359/B4C through electromagnetic stir casting. Indian J. Eng. Mater. Sci. 2016, 23, 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Chandla, N.K.; Kant, S.; Goud, M.M. Mechanical, tribological and microstructural characterization of stir cast Al-6061 metal/matrix composites—A comprehensive review. Sādhanā 2021, 46, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhukar, P.; Mishra, V.; Selvaraj, N.; Rao, C.S.P.; Gonal Basavaraja, V.K.; Seetharam, R.; Chavali, M.; Mohammad, F.; Soleiman, A.A. Influence of Ultrasonic Vibration towards the Microstructure Refinement and Particulate Distribution of AA7150-B4C Nanocomposites. Coatings 2022, 12, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharath, B.N.; Madhu, P.; Verma, A. Wear behaviour of aluminium-based hybrid composites processed by equal channel angular pressing. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2024, 238, 1079–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayendra, B.; Kumar, S.S.; Singh, V. Mechanical Characterization of Stir Cast Al-7075/B4C/Graphite Reinforced Hybrid Metal Matrix Composites. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 21, 1104–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.M.; Chen, X.; Li, D.Y. Electrochemical Behavior of Al-B4C Metal Matrix Composites in NaCl Solution. Materials 2015, 8, 6455–6470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; He, S.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, P. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Al6061-31vol.%B4C composites prepared by hot isostatic pressing. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2015, 24, 4044–4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, A.; Kumar, R.; Beemkumar, N.; Kumar, A.V.; Singh, G.; Kulshreshta, A.; Mann, V.S.; Santhosh, A.J. Casting of particle reinforced metal matrix composite by liquid state fabrication method: A review. Res. Eng. 2024, 24, 103152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Zaman, A.U.; Khan, K.I.; Karim, M.R.A.; Hussain, A.; Haq, E.U. Synergistic Effects of Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) and White Graphite (h-BN), on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Aluminum Matrix Composites. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 49, 9611–9624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Luo, X. Reinforcement of aluminum metal matrix composites through graphene and graphene-like monolayers: A first-principles study. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 9596–9603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, Y.J.; Luo, H.; Zhang, J.J.; Zhang, P.C. Liquid Phase Flow Behavior and Densification Mechanism of Al/B4C Composites Fabricated via Semisolid Hot Isostatic Pressing. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2019, 48, 3102–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.J.; Liu, X.Q.; Liu, Z.L.; Liu, B.L. The Monte Carlo simulation of neutron shielding performance of boron carbide reinforced with aluminum composites. Acta Phys. Sin. 2013, 62, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiruppathi, K.; Aravindan, S.; Gupta, M. Densification Studies on Aluminum-Based Brake Lining Composite Processed by Microwave and Spark Plasma Sintering. Powder Met. Met. Ceram. 2021, 60, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.X.; Yu, H.S.; Zeng, D.X.; Shen, P. Wire-powder-arc additive manufacturing: A viable strategy to fabricate carbide ceramic/aluminum alloy multi-material structures. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 51, 102637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, M.V.; Manonmani, K. Mechanical and tribological characteristics of aluminium hybrid composites reinforced with boron carbide and titanium diboride. Ceram.-Silik. 2022, 66, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.H.; Ortalan, V.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Z.H.; Vogt, R.G.; Browning, N.D.; Lavernia, E.J.; Schoenung, J.M. Investigation of aluminum-based nanocomposites with ultra-high strength. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2009, 527, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, X.M.; Qian, D.Z.; Zhang, Z.H.; Huang, H.W.; Guo, H.B. Thermal Safety Analysis of Aluminum Matrix B4C In-Pile Irradiation. At. Energy Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 454–458. [Google Scholar]

- Sekhar, R.A.; Pillai, R.R.; Ali, M.M.; Kumar, C.N.S. Enhanced mechanical and wear properties of aluminium-based composites reinforced with a unique blend of granite particles and boron carbide for sustainable material recycling. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 963, 171165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, Z.; Ren, L. Study on the Mechanical Properties of Bionic Coupling Layered B4C/5083Al Composite Materials. Materials 2018, 11, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meignanamoorthy, M.; Ravichandran, M.; Mohanavel, V.; Afzal, A.; Sathish, T.; Alamri, S.; Khan, S.A.; Saleel, C.A. Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Corrosion Behavior of Boron Carbide Reinforced Aluminum Alloy (Al-Fe-Si-Zn-Cu) Matrix Composites Produced via Powder Metallurgy Route. Materials 2021, 14, 4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.H.; Zhang, C.; He, L.K.; Meng, Q.N.; Liu, B.C.; Gao, K.; Wu, J.H. Enhanced bending strength and thermal conductivity in diamond/Al composites with B4C coating. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nečas, D.; Voňavková, I.; Pinc, J.; Dvorský, D.; Kubásek, J. Nanograined Zinc Alloys with Improved Mechanical Properties Prepared by Powder Metallurgy. Microsc. Microanal. 2023, 29 (Suppl. S1), 169–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Huang, P.; Sun, X.; Zeng, W.; Zhang, J.; Zu, G. Fatigue of an Aluminum Foam Sandwich Formed by Powder Metallurgy. Materials 2023, 16, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernsmann, J.-S.L.; Hillebrandt, S.; Rommerskirchen, M.; Bold, S.; Schleifenbaum, J.H. On the Use of Metal Sinter Powder in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Processing (PBF-LB/M). Materials 2023, 16, 5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, X.Y.; Qu, X.H.; Qin, M.L.; Que, Z.Y.; Wei, Z.C.; Guo, C.G.; Lu, X.; Dong, Y.H. Powder Metallurgy Route to Ultrafine-Grained Refractory Metals. Adv Mater. 2023, 35, e2205807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Rufner, J.F.; LaGrange, T.B.; Campbell, G.H.; Lavernia, E.J.; Schoenung, J.M.; van Benthem, K. Metal/ceramic interface structures and segregation behavior in aluminum-based composites. Acta Mater. 2015, 95, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Zhang, J.; Xie, H.; Li, F.; Huang, Z.; Yuan, G.; Zhang, J.; Jia, Q.; Zhang, H.; Yeprem, H.A.; et al. Preparation of B4Cp/Al Composites via Selective Laser Melting and Their Tribological Properties. Materials 2022, 15, 8340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangadurai, K.R.; Ramesh, T. Synthesis and cold upsetting behavior of stir casted AA6061-B4Cp composites. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2014, 73, 394–399. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, A.; Kumar, A.; Purohit, R. Characterization, Strength and Wear Optimization of Aluminium Based Boron Carbide/Graphite Hybrid Composite by TOPSIS for Dry Condition. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2023, 12, 127005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramono, A.; Kommel, L.; Koll, L.; Veinthal, R. The Aluminum Based Composite Produced by Self Propagating High Temperature Synthesis. Mater. Sci. 2016, 22, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Singh, G.; Singh, K.; Vardhan, S. Evaluation of mechanical performance on a developed AA 6061matrix-Mg/0.9-Si/0.68 reinforced with B4C based composites. Funct. Compos. Struct. 2021, 3, 01154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butola, R.; Pandey, K.D.; Murtaza, Q.; Walia, R.S.; Tyagi, M.; Srinivas, K.; Chaudhary, A.K. Experimental analysis and optimization of process parameters using response surface methodology of surface nanocomposites fabricated by friction stir processing. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part N-J. Nanomater. Nanoeng. Nanosyst. 2024, 238, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butola, R.; Chandra, P.; Bector, K.; Singari, R.M. Fabrication and multi-objective optimization of friction stir processed aluminium based surface composites using Taguchi approach. Surf. Topogr. Metrol. Prop. 2021, 9, 025044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodabakhshi, F.; Gerlich, A.P.; Worswick, M. Fabrication and characterization of a high strength ultra-fine grained metal-matrix AA8006-B4C layered nanocomposite by a novel accumulative fold-forging (AFF) process. Mater. Des. 2018, 157, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

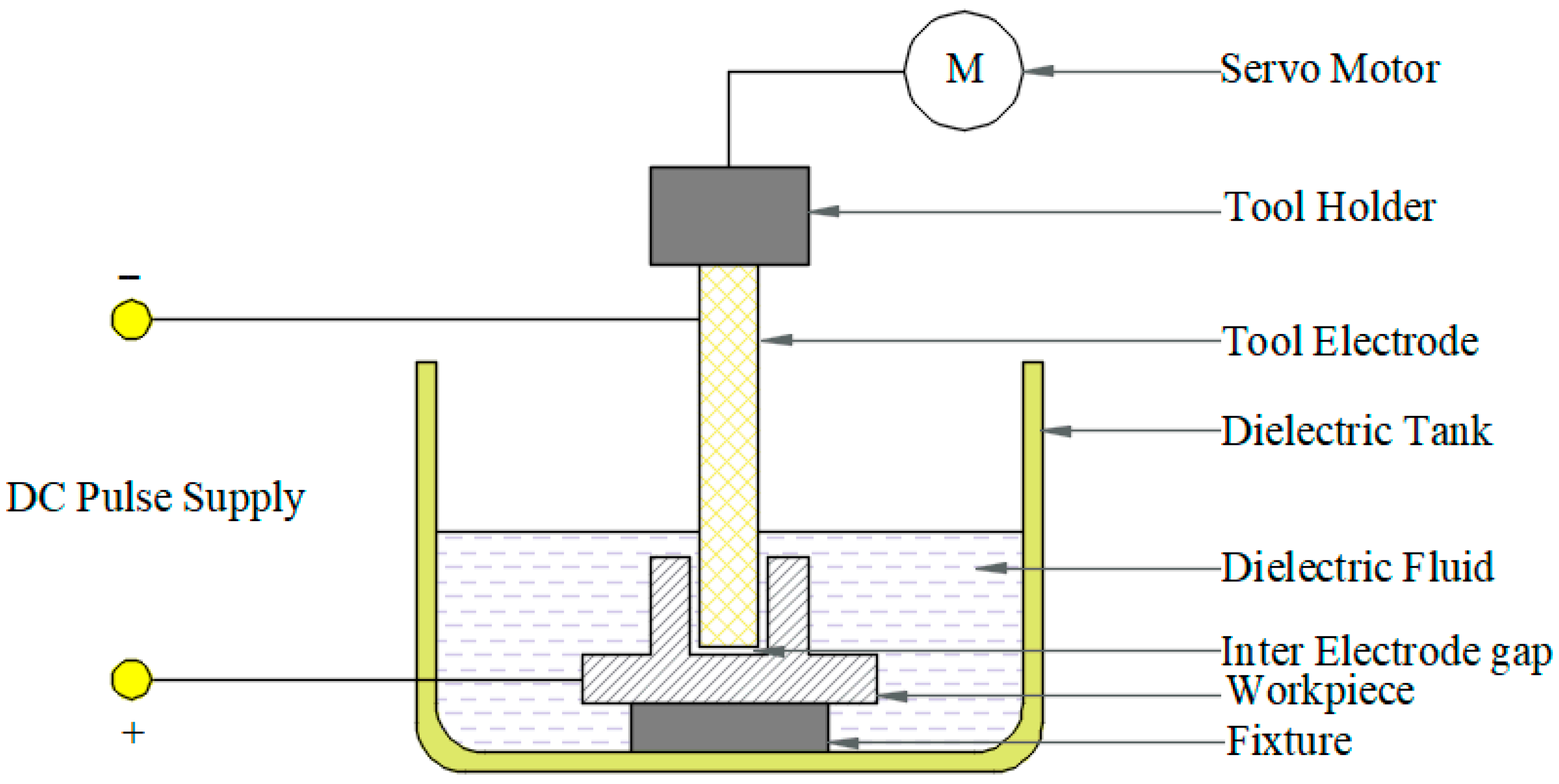

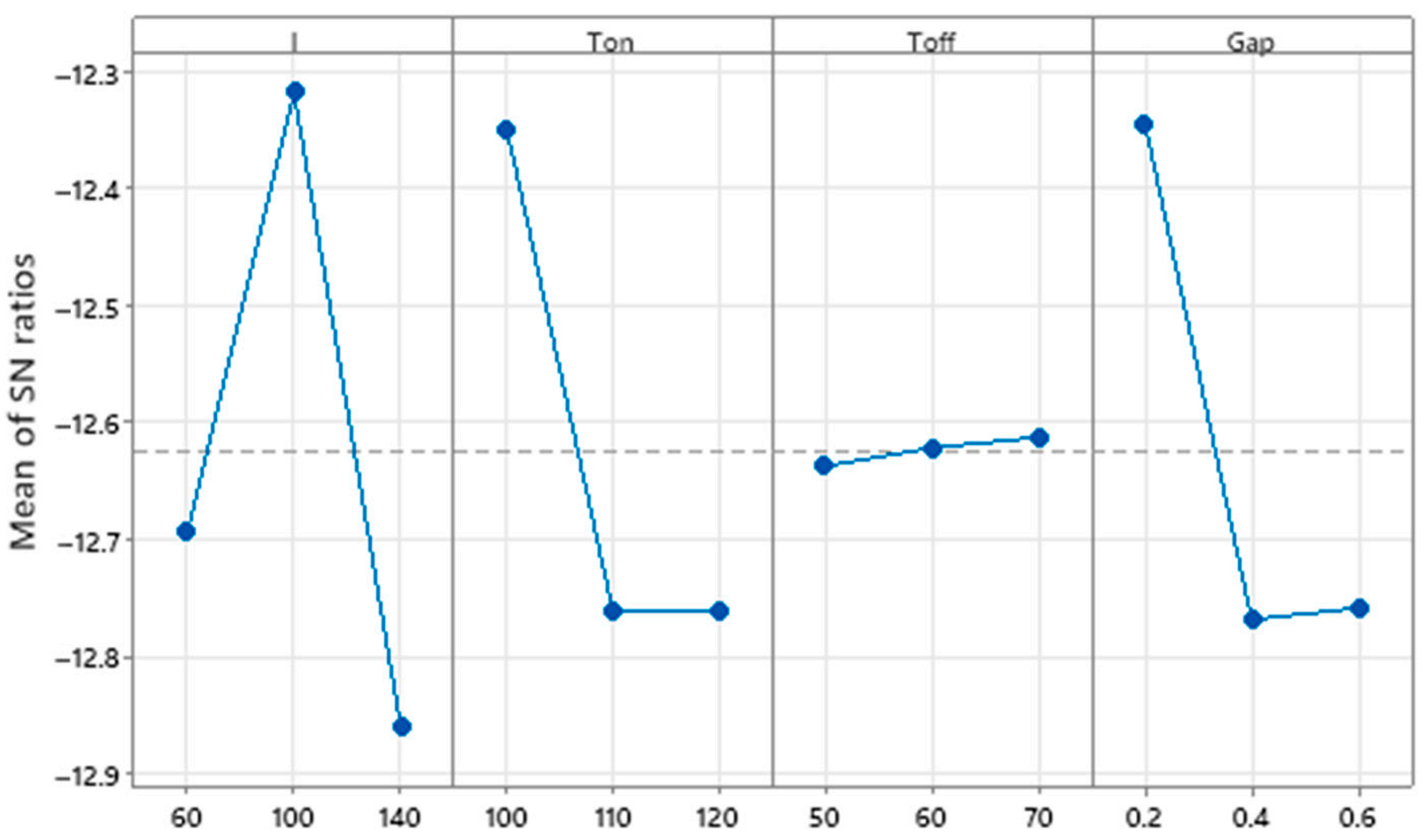

- Mohankumar, V.; Rajeshkannan, A.; Sureshkannan, G. A Hybrid Design of Experiment Approach in Analyzing the Electrical Discharge Machining Influence on Stir Cast Al7075/B4C Metal Matrix Composites. Metals 2024, 14, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Liu, Y.L.; Li, L.; Huang, J.H.; Zou, S.L.; Ren, Z.H.; Liu, S.H.; Wang, Y.L. Microstructure, mechanical, and corrosion properties of B4C/Al composites with excellent ductility fabricated by laser-directed energy deposition. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2025, 20, e2505991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilbas, B.S.; Karatas, C.; Karakoc, H.; Aleem, B.J.A.; Khan, S.; Al-Aqeeli, N. Additive manufacturing of ceramic particle-reinforced aluminum-based metal matrix composites: A review. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 19212–19242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilbas, B.S.; Karatas, C.; Karakoc, H.; Abdul Aleem, B.J.; Khan, S.; Al-Aqeeli, N. Laser surface treatment of aluminum based composite mixed with B4C particles. Opt. Laser Technol. 2015, 66, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abenojar, J.; Bautista, A.; Guzman, S.; Velasco, F.; Martinez, M.A. Study Through Potentiodynamic Techniques of the Corrosion Resistance of Different Aluminium Base MMC’s with Boron Additions. Mater. Sci. Forum 2010, 660–661, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vairamuthu, J.; Senthil Kumar, B. Synthesis and electrochemical behaviour of TiC- and B4C-reinforced Al-based metal matrix composite. Emerg. Mater. Res. 2021, 10, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziani, A.; Delmotte, F.; Le Paven-Thivet, C.; Meltchakov, E.; Jérome, A.; Roulliay, M.; Bridou, F.; Gasc, K. Ion beam sputtered aluminum based multilayer mirrors for extreme ultraviolet solar imaging. Thin Solid Films 2014, 552, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Niu, J.; Huang, J.; Fan, D.; Yu, S.; Ma, Y.; Yu, X. The Effect of B4C Powder on Properties of the WAAM 2319 Al Alloy. Materials 2023, 16, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, A.; Taheri-Nassaj, E.; Khosroshahi, R.A. Creep behavior and wear resistance of Al 5083 based hybrid composites reinforced with carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and boron carbide (B4C). J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 650, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.K.; Kumar, R.; Dwivedi, S.P. Role of ceramic particulate reinforcements on mechanical properties and fracture behavior of aluminum—Based composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 745, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.B.; Chakoumakos, B.C.; Rawn, C.J. Characterization of shielding materials used in neutron scattering instrumentation. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 2019, 946, 162708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

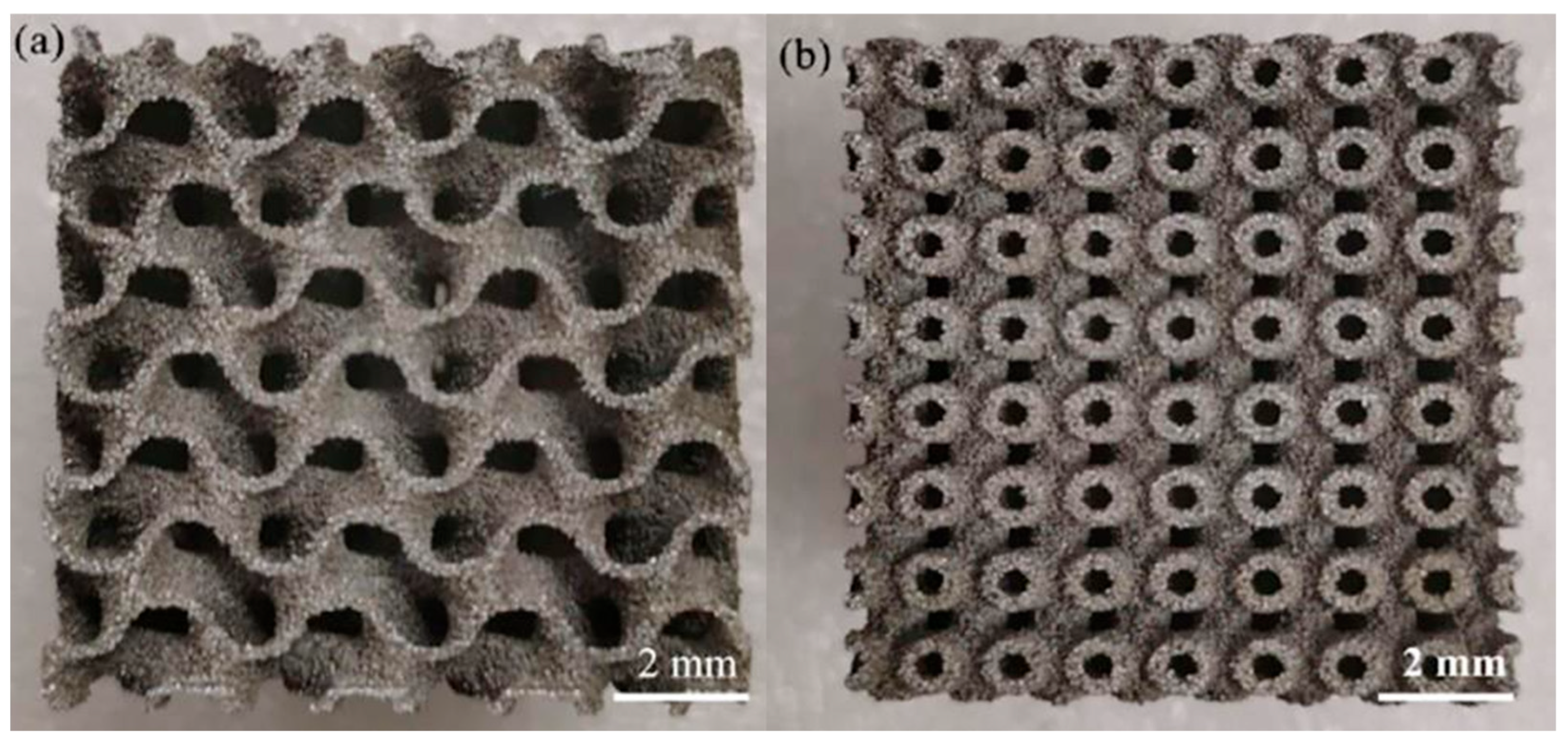

- Stone, M.B.; Kolesnikov, A.I.; Fanelli, V.R.; May, A.F.; Bai, S.; Liu, J. Characterization of aluminum and boron carbide based additive manufactured material for thermal neutron shielding. Mater. Des. 2024, 237, 112463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emiru, A.A.; Ayalew, E.A.; Sinha, D.K. Fabrication and characterization of hybrid aluminium (al6061) metal matrix composite reinforced with sic, B4C and MoS2 via stir casting. Int. J. Met. 2023, 17, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Murtaza, Q.; Gupta, P. Synergetic Effect of Gr-B4C Reinforcement on the Structural and Mechanical Properties of AA6351 Hybrid Metal Matrix Composites. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2023, 12, 067002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, N.R.J.; Raja, S.; Tharmaraj, R.; Pruncu, C.I.; Dispinar, D. Mechanical and tribological characteristics of boron carbide reinforcement of AA6061 matrix composite. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2020, 42, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasubramanian, K.; Arumugam, P.R.; Sankaran, S. Investigation on tribological behavior of boron doped diamond coated cemented tungsten carbide for cutting tool applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 332, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Fu, W.; Ma, L.; Li, X.; Wang, H. Cold spraying B4C particles reinforced aluminium coatings. Surf. Eng. 2019, 35, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, S.T.; Uthayakumar, M.; Kumar, S.S. Micro-grooving of aluminum-based composites using nd:yag laser machining. Surf. Rev. Lett. 2023, 30, 2350078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, P.; Singh, P.K. Experimental investigation on microstructure, mechanical and machining properties of Al-4032/granite marble powder (GMP) composite produced through stir casting. Mater. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2022, 53, 1450–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskesen, A.; Kutay, D. Analysis of thrust force in drilling B4C-reinforced aluminium alloy using genetic learning algorithm. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2014, 75, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Uthayakumar, M.; Kumaran, S.T.; Parameswaran, P.; Haneef, T.K.; Mukhopadhyay, C.K.; Rao, B.P.C. Performance Monitoring of WEDM Using Online Acoustic Emission Technique. Silicon 2018, 10, 2635–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarasu, S.; Subramanian, M.; Thangasamy, J. An effect of nano-SiC with different dielectric mediums on AZ61/7.5% B4C nanocomposites studied through electrical discharge machining and Taguchi based complex proportional assessment method. Matéria 2023, 28, e20230058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvanimoghaddam, K.; Khayyam, H.; Abdizadeh, H.; Karbalaei Akbari, M.; Pakseresht, A.H.; Ghasali, E.; Naebe, M. Boron carbide reinforced aluminium matrix composite: Physical, mechanical characterization and mathematical modelling. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 658, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironovs, V.; Usherenko, Y.; Boiko, I.; Kuzmina, J. Recycling of Aluminum-Based Composites Reinforced with Boron-Tungsten Fibres. Materials 2022, 15, 3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorehead, C.A.; Karthikeyan, S.; Odegard, G.M. Meso-scale microstructural agglomerate quantification in boron carbide using X-ray microcomputed tomography. Mater. Charact. 2018, 141, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.A.; Devaraju, A.; Arunkumar, S. Mechanical properties and microstructure of stir casted Al/B4C/garnet composites. Mater. Test. 2017, 59, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Lavernia, E.J.; Schoenung, J.M. Particulate reinforced aluminum alloy matrix composites—A review on the effect of microconstituents. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2017, 48, 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Jamaludeen, U.M.; Ramabalan, S. Analysis and Multi-Response Optimization of Friction Stir Welding Parameters for Stir-Cast AA6092/B4C/ZrO2 Hybrid Composites. Mater. Res. 2025, 28, 20250185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, R.; Sharma, N.; Bansal, S.A. A review on recent developments of aluminum-based hybrid composites for automotive applications. Emerg. Mater. 2021, 4, 1243–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, N.R.J.; Raja, S.; Tharmaraj, R.; Pruncu, C.I.; Dispinar, D. Optimization of dry sliding wear behavior of aluminium-based hybrid MMC’s using experimental and DOE methods. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 16, 743–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, R.; Xavior, M.A. Analytical, numerical and experimental approach for design and development of optimal die profile for the cold extrusion of B4C DRMM Al 6061 composite billet into hexagonal section. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2014, 28, 5117–5127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alattar, A.L.; Hamzah, M.K. Increase in the Physicomechanical Properties of Aluminum Alloys Reinforced with Boron Carbide Particles. Russ. Met. 2023, 2023, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panneerselvam, T.; Senthil, P.; Raghuraman, S. Tribological study on hybrid reinforced aluminium-based metal matrix composites. Int. J. Surf. Sci. Eng. 2018, 12, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundararajan, R.; Ramesh, A.; Sivasankaran, S.; Vignesh, M. Modeling and Analysis of Mechanical Properties of Aluminium Alloy (A413) Reinforced with Boron Carbide (B4C) Processed Through Squeeze Casting Process Using Artificial Neural Network Model and Statistical Technique. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 2008–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.G.; Gong, J.J.; Jie, S. Neutron Shielding Properties of TPX/B4C Composites Based on Monte Carlo Method. In Proceedings of the Asia Conference on Geological Research and Environmental Technology (GRET), Kamakura, Japan, 10–11 October 2020; Electr Network. Volume 632, p. 052037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Uthayakumar, M.; Kumaran, S.T.; Parameswaran, P.; Mohandas, E.; Kempulraj, G.; Babu, B.S.R.; Natarajan, S.A. Parametric optimization of wire electrical discharge machining on aluminium based composites through grey relational analysis. J. Manuf. Processes 2015, 20, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, J.; Bohlen, A.; Kamboj, N.; Seefeld, T. Automated Determination of Grain Features for Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2023, 32, 10402–10411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjong, S.C.; Ma, Z.Y. High cycle fatigue response of in-situ Al-based composites containing TiB2 and Al2O3 submicron particles. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2005, 65, 1537–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatkar, S.K.; Suri, N.M.; Kant, S.; Kumar, P. A review on mechanical and tribological properties of graphite reinforced self lubricating hybrid metal matrix composites. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2018, 56, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Process | B4C Content (wt.%) | Relative Density (%) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Microhardness (HV) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Vacuum Sintering | 30 | 91.9 | 86 | 52 | [38] |

| Semi-solid HIP | 30 | 99.6 | 301 | 128 | [38] |

| Microwave Sintering | 10 | 92.3 | 110 | 61.5 | [40] |

| SPS | 10 | 98.7 | 235 | 189.3 | [40] |

| Parameter | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current (I, A) | 60 | 100 | 140 |

| Pulse ON Time (Ton, ms) | 100 | 110 | 120 |

| Pulse OFF Time (Toff, ms) | 50 | 60 | 70 |

| Electrode Gap (Gap, mm) | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| Fabrication Method | Process Characteristics | B4C Content (wt.%) | Typical Properties | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIP | Densification under high temperature/pressure; uniform reinforcement distribution | 10–35 | Tensile strength > 300 MPa; elongation > 3% | [38] |

| SPS | Rapid sintering process; refined grain structure | 10–20 | High relative density; significantly enhanced microhardness | [40] |

| Stir Casting | Low-cost; suitable for mass production | 5–15 | Hardness increases with B4C content | [35] |

| ECAP | Significant grain refinement; improved mechanical properties | 5–15 | Enhanced hardness and wear resistance with increasing passes | [31] |

| Process Type | Equipment Investment (kUSD) | Material Cost (USD/kg) | Energy Cost (USD/kg) | Unit Production Cost (USD/kg) | Suitable Production Scale | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECAP | 110–165 | 6.9–11 | 0.35 | 0.7–1.4 | Mass Production (>100 tons/yr) | [31] |

| LPBF (AM) | 415–690 | 110–138 | 6.9–11 | 28–69 | Small Batch (<5 tons/yr) | [41,64] |

| WPA-AM (AM) | 207–276 | 83–110 | 5.5–8.3 | 17–25 | Medium-Small Batch (5–20 tons/yr) | [41] |

| Fabrication Method | Process Characteristics | Typical B4C Content (wt.%) | Key Properties | Typical Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Powder Metallurgy (HIP) | High temp/pressure; liquid-phase sintering & densification | 30 | High relative density (99.6%), Tensile strength (301 MPa) | Nuclear shielding, Spent fuel storage containers | [38] |

| Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) | Rapid sintering; Plasma activation | 10 | High microhardness (189.3 HV), High relative density (98.7%) | Armor plates, Personal protection | [40] |

| Stir Casting | Low cost, mass production; Parameter sensitivity | 15 | Increased hardness with content; Tensile strength (203 MPa) | Automotive brake rotors, Structural supports | [35,55] |

| Melt Infiltration | Suitable for high volume fractions; Uniform distribution | >20 | High density (96.8%), Good tensile strength (267 MPa) | High-performance neutron absorbers | [57] |

| ECAP/FSP | Severe plastic deformation; Grain refinement | 5–15 | Significantly enhanced hardness and wear resistance | Aerospace wear-resistant components | [31,59] |

| Additive Manufacturing (AM) | Complex geometry formation; Multi-material/Gradient design capability | 5–15 | High strength (320 MPa) with good ductility | Aerospace lightweight structures, Custom functional parts | [63,64] |

| Surface Composite Technology | Substrate surface modification; Cost-effective | 5–15 | Enhanced surface hardness, wear and corrosion resistance | Electronic packaging, Space optical components | [65,67] |

| Element | Electron Configuration | Radius Cut-Off (Bohr) |

|---|---|---|

| Aluminum (Al) | 3s2 3p1 | 1.90 |

| Carbon (C) | 2s2 2p2 | 1.51 |

| Silicon (Si) | 3s2 3p2 | 1.91 |

| Phosphorus (P) | 3s2 3p3 | 1.91 |

| Boron (B) | 2s2 2p1 | 1.70 |

| Nitrogen (N) | 2s2 2p3 | 1.20 |

| B4C Content (wt.%) | Load (N) | Sliding Speed (m/s) | Condition | Wear Rate (×10−6 mm3/Nm) | Interface Temperature (°C) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 10 | 1.0 | Dry | 2.8 | 50 | [76] |

| 15 | 30 | 1.0 | Dry | 8.5 | 95 | [76] |

| 10 | 20 | 0.5 | Dry | 3.2 | 42 | [75] |

| 10 | 20 | 2.0 | Dry | 6.7 | 180 | [75] |

| 10 | 20 | 1.0 | Oil lubrication | 1.2 | 35 | [74] |

| Performance Category | Typical Indicators | Primary Influencing Factors | Optimization Strategies | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength | 200–365 MPa | B4C content, interfacial bonding, heat treatment | Hybrid reinforcement, interface modulation | [42,70] |

| Compressive Strength | Up to 1065 MPa | Reinforcement phase size, uniform distribution | Nano-reinforcement, severe plastic deformation | [43,61] |

| Hardness | Increased by 50–106% | B4C content, particle size | Optimized reinforcement ratio, heat treatment | [70] |

| Neutron Shielding | Transmission coefficient reduced by 90% | 10B areal density, material thickness | High B4C content, gradient design | [6] |

| Thermal Conductivity | Increased by 46.4% | Reinforcement phase size, distribution | Large-sized particles, functional gradient | [53] |

| Wear Resistance | Improved by 3–20 times | B4C content, lubricating phase | Addition of solid lubricants | [75] |

| Corrosion Resistance | Decreases with increased B4C | Interfacial galvanic corrosion | Surface treatment, alloying | [79] |

| Composite Type | Reinforcement Content | Theoretical Density (g/cm3) | Sintered/As-built Density (g/cm3) | Relative Densification (%) | Porosity (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BN/Al | 1 wt.% BN | 2.69 | 2.55 | 95.5 | 4.4 | [36] |

| BN/Al | 3 wt.% BN | 2.68 | 2.60 | 96.8 | 3.1 | [36] |

| BN-CNTs/Al | 3 wt.% BN + 0.5 wt.% CNTs | 2.69 | 2.63 | 97.7 | 2.2 | [36] |

| B4C/Al (SLM) | 20 wt.% B4C (scanning speed: 100 mm/s) | 2.81 | 2.73 | 97.1 | 2.9 | [54] |

| B4C/Al (SLM) | 20 wt.% B4C (scanning speed: 700 mm/s) | 2.81 | 2.39 | 85.0 | 15.0 | [54] |

| Application Field | Critical Performance Requirements | Typical Application Cases | Advantages/Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear shielding | High neutron absorption (Σa), radiation resistance | Reactor control rods, spent fuel containers | 10B enrichment (≥19.8%), low activation | [6] |

| Military armor | Ballistic limit (V50), hardness (≥70 HRC) | Vehicle armor plates, personal protection | High hardness-to-density ratio (8.5 GPa·cm3/g) | [20] |

| Aerospace components | Specific strength (≥380 MPa·cm3/g), thermal stability | Satellite structural parts, UAV frames | Low CTE (6.5 × 10−6/K), vibration damping | [22,36,89] |

| Automotive lightweight | Wear resistance (≤3 × 10−6 mm3/Nm), cost efficiency | Brake rotors, suspension arms | 40% weight reduction vs. steel | [22,90] |

| Thermal management | Thermal conductivity (≥180 W/m·K), dimensional stability | CPU heat sinks, power modules | Tunable CTE matching Si | [37,65,68] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, C.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Bian, M.; Kang, X.; Yang, X. Recent Advances on Aluminum-Based Boron Carbide Composites: Performance, Fabrication, and Applications. Materials 2025, 18, 5469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235469

Chen C, Li B, Wang Y, Bian M, Kang X, Yang X. Recent Advances on Aluminum-Based Boron Carbide Composites: Performance, Fabrication, and Applications. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235469

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Caixia, Baocheng Li, Yun Wang, Ming Bian, Xiaomin Kang, and Xun Yang. 2025. "Recent Advances on Aluminum-Based Boron Carbide Composites: Performance, Fabrication, and Applications" Materials 18, no. 23: 5469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235469

APA StyleChen, C., Li, B., Wang, Y., Bian, M., Kang, X., & Yang, X. (2025). Recent Advances on Aluminum-Based Boron Carbide Composites: Performance, Fabrication, and Applications. Materials, 18(23), 5469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235469