Effect of Heat Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Mg-3.2Nd-2.5Gd-0.4Zn-0.5Zr (wt.%) Alloy

Highlights

- An optimal T6 treatment (520 °C × 10 h + 200 °C × 16 h) was established for the Mg-3.2Nd-2.5Gd-0.4Zn-0.5Zr alloy.

- The T6-treated alloy achieves a high-temperature UTS of 292 MPa at 150 °C while retaining high room-temperature strength.

- The enhanced strength and Brinell hardness primarily resulted from a high number density of β′ precipitates.

Abstract

1. Introduction

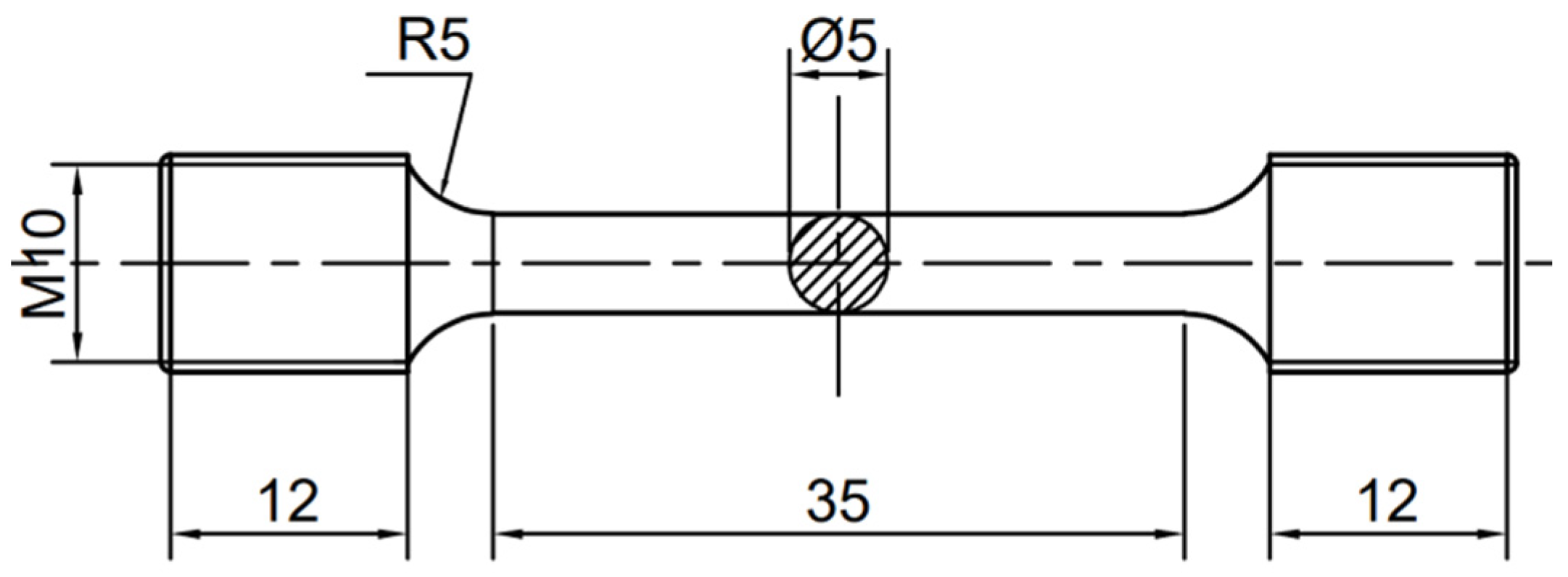

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

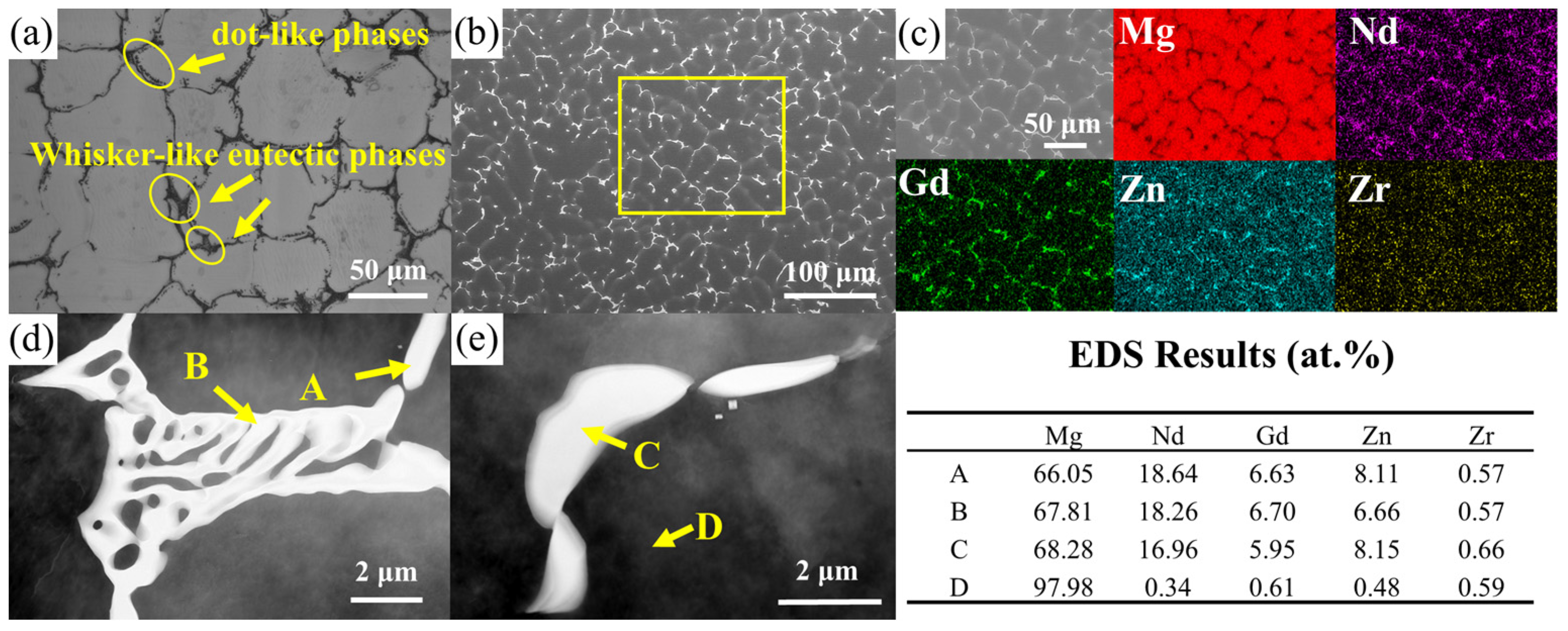

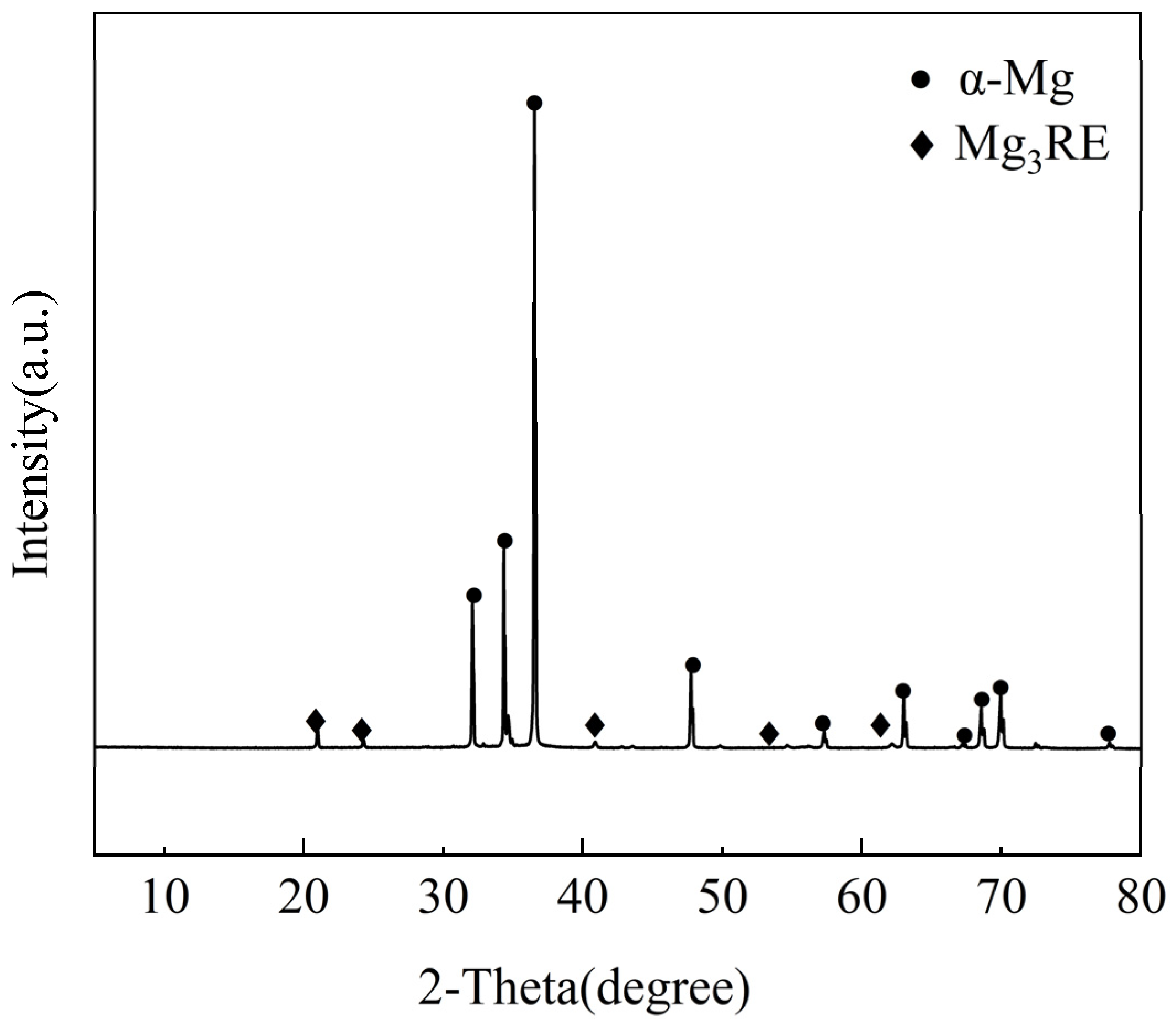

3.1. Microstructural Observation of As-Cast Alloy

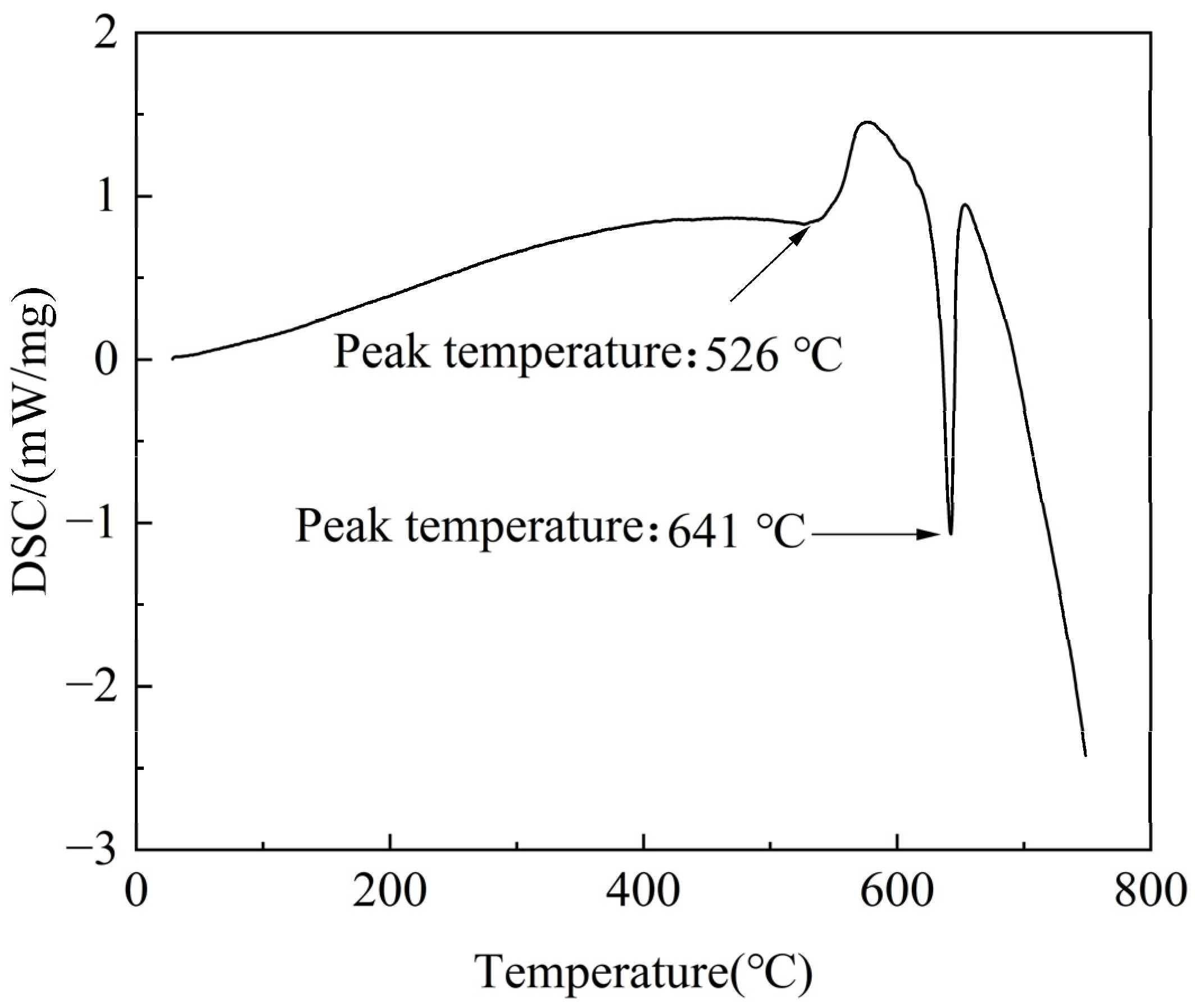

3.2. Solution Treatment

3.3. Age Hardening Behavior and Precipitate

3.4. Characterization of Mechanical Properties and Fracture Surface Morphology

4. Conclusions

- The as-cast microstructure composes of an α-Mg matrix with Mg3RE phases distributed along grain boundaries and within grain interiors. The average grain size was measured to be 27.25 μm.

- Based on systematic hardness measurements, mechanical property testing, and microstructural characterization of the T6-treated alloy, the optimal heat treatment regime was established as solution treatment at 520 °C for 10 h then aging at 200 °C for 16 h.

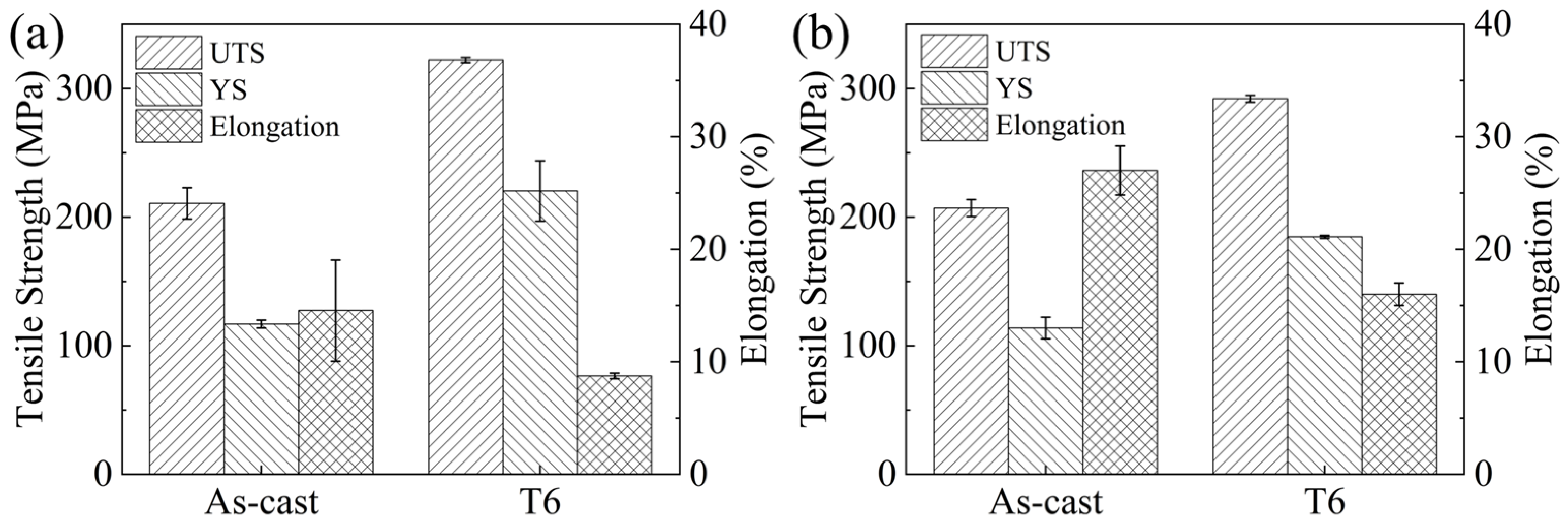

- After T6 treatment, the experimental alloy achieves UTS and YS of 322 ± 2.0 MPa and 220 ± 23.0 MPa at room temperature, representing increases of 53% and 88%, respectively, compared with the as-cast condition, with an EL of 8.7 ± 0.2%. When tested at 150 °C, the UTS and YS reach 292 ± 2.6 MPa and 185 ± 1.1 MPa (increases of 41% and 62% over the as-cast alloy), accompanied by an EL of 16 ± 1.0%.

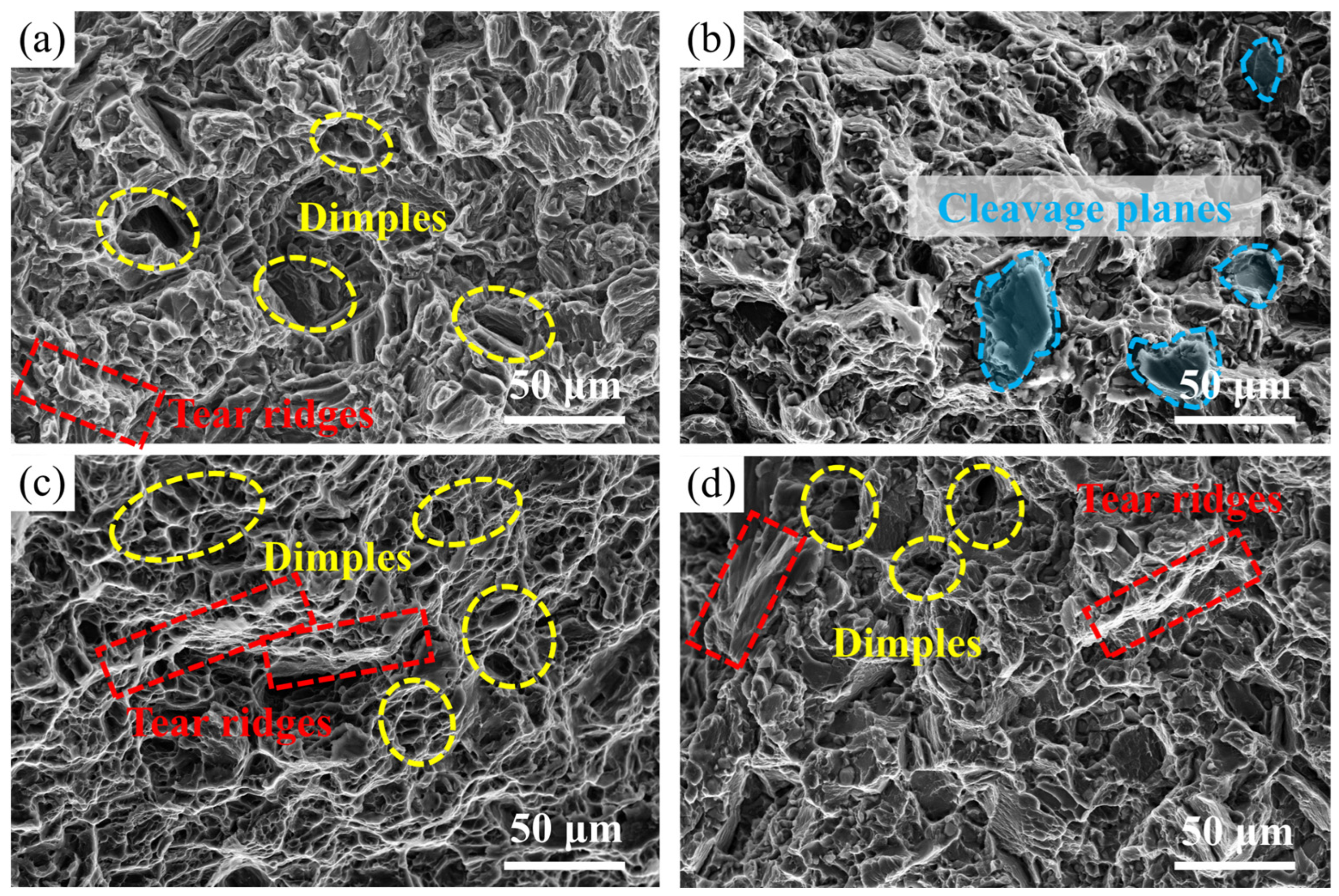

- The fracture mode of the Mg-3.2Nd-2.5Gd-0.4Zn-0.5Zr alloy exhibits significant variations with heat treatment condition and testing temperature. At room temperature, the as-cast alloy undergoes ductile fracture with dimples, whereas the T6-treated alloy displays quasi-cleavage brittle fracture due to the strong pinning effect of fine β′ precipitates. At 150 °C, both the as-cast and T6-treated alloys transition to predominantly ductile fracture characterized by abundant dimples, where thermal activation at elevated temperature enhances plasticity by facilitating additional slip.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meier, J.M.; Caris, J.; Luo, A.A. Towards high strength cast Mg-RE based alloys: Phase diagrams and strengthening mechanisms. J. Magnes. Alloys 2022, 10, 1401–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.H.; Jie, W.Q.; Yang, G.Y. Effect of gadolinium on aged hardening behavior, microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg-Nd-Zn-Zr alloy. Trans. Nonferr. Met. Soc. China 2008, 18, s27–s32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.S.; Yang, M.B.; Chen, X.H. A Review on Casting Magnesium Alloys: Modification of Commercial Alloys and Development of New Alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2016, 32, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.C.; Chang, Z.Y.; Su, N.; Luo, J.; Liang, Y.Y.; Jin, Y.H.; Wu, Y.J.; Peng, L.M.; Ding, W.J. Developing a novel high-strength Mg-Gd-Y-Zn-Mn alloy for laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing process. J. Magnes. Alloys 2025, 13, 3713–3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xiong, X.M.; Chen, J.; Peng, X.D.; Chen, D.L.; Pan, F.S. Research advances in magnesium and magnesium alloys worldwide in 2020. J. Magnes. Alloys 2021, 9, 705–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, T.M. Weight loss with magnesium alloys. Science 2010, 328, 986–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, D.S.; Sasanka, C.T.; Ravindra, K.; Suman, K.N.S. Magnesium and its alloys in automotive applications—A review. Am. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2015, 4, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.C.; Yang, Y.; Peng, X.D.; Song, J.F.; Pan, F.S. Overview of advancement and development trend on magnesium alloy. J. Magnes. Alloys 2019, 7, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Wang, L.; Zhao, S.; Wang, L.; Guo, E. Strengthening of Mg Alloy with Multiple RE Elements with Ag and Zn Doping via Heat Treatment. Materials 2023, 16, 4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.B.; Pan, H.C.; Ren, Y.P.; Sun, S.; Wang, L.Q.; He, Y.F.; Qin, G.W. Co-existences of the two types of β’ precipitations in peak-aged Mg-Gd binary alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 738, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, D.H.; Hono, K.; Nie, J.F. Atom probe characterization of plate-like precipitates in a Mg–RE–Zn–Zr casting alloy. Scr. Mater. 2003, 48, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Chen, S. Microstructure Evolution and Mechanical Properties of As-Cast and As-Compressed ZM6 Magnesium Alloys during the Two-Stage Aging Treatment Process. Materials 2021, 14, 7760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Wang, J.F.; Wang, J.X.; Yu, D.; Zheng, W.X.; Xu, C.B.; Lu, R.P. Effect of lamellar LPSO phase on mechanical properties and damping capacity in cast magnesium alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 22, 2589–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.G.; Fu, P.H.; Peng, L.M.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.Q.; Hu, G.Q.; Ding, W.J. Microstructure and mechanical properties of laser melting deposited GW103K Mg-RE alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 687, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Han, D.; Wang, M.; Cai, T.; Liang, N.; Beausir, B.; Liu, H.; Yang, S. The Effect of Rotary-Die Equal-Channel Angular Pressing Process on the Microstructure, the Mechanical and Friction Properties of GW103 Alloy. Materials 2022, 15, 9005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Yao, M.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Xing, Z.; Xia, X.; Liu, P.; Wan, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, H. Effects of an LPSO Phase Induced by Zn Addition on the High-Temperature Properties of Mg-9Gd-2Nd-(1.5Zn)-0.5Zr Alloy. Materials 2024, 17, 4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, K.; Zhang, L.; Wu, G.H.; Liu, W.C.; Ding, W.J. Effect of Y and Gd content on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg–Y–RE alloys. J. Magnes. Alloys 2019, 7, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, A.; Das, M.; Balla, V.K. Effect of heat treatment on microstructure, mechanical, corrosion and biocompatibility of Mg-Zn-Zr-Gd-Nd alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 821, 153462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.M.; Zeng, X.Q.; Peng, L.M.; Gao, X.; Nie, J.F.; Ding, W.J. Microstructure and strengthening mechanism of high strength Mg–10Gd–2Y–0.5Zr alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2007, 427, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandlöbes, S.; Zaefferer, S.; Schestakow, I.; Yi, S.; Gonzalez-Martinez, R. On the role of non-basal deformation mechanisms for the ductility of Mg and Mg–Y alloys. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.F. Precipitation and Hardening in Magnesium Alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2012, 43, 3891–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.S.; Zhang, J.H.; You, Z.H.; Liu, S.J.; Guan, K.; Wu, R.Z.; Wang, J.; Feng, J. Towards developing Mg alloys with simultaneously improved strength and corrosion resistance via RE alloying. J. Magnes. Alloys 2021, 9, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Wu, G.H.; Zhang, X.L.; Liu, W.C.; Ding, W.J. The role of Gd on the microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of Mg-3Nd-0.2Zn-0.5Zr alloy. Mater. Charact. 2021, 175, 111076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.B.; Zhao, Y.H.; Lu, R.P.; Yuan, M.N.; Wang, Z.J.; Li, H.J.; Hou, H. Effect of Zn addition on microstructure and mechanical properties of cast Mg-Gd-Y-Zr alloys. Trans. Nonferr. Met. Soc. China 2019, 29, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Das, A. Grain refinement of magnesium alloys by zirconium: Formation of equiaxed grains. Scr. Mater. 2006, 54, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.J.; Wu, G.H.; Liu, W.C.; Pang, S.; Ding, W.J. Effect of heat treatment on microstructures and mechanical properties of sand-cast Mg–4Y–2Nd–1Gd–0.4Zr magnesium alloy. Trans. Nonferr. Met. Soc. China 2012, 22, 1540–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.C.; He, Z.L.; Fu, P.H.; Wu, Y.J.; Peng, L.M.; Ding, W.J. Heat treatment and mechanical properties of a high-strength cast Mg–Gd–Zn alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 651, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, K.; Zeng, X.Q.; Chen, B.; Wang, Y.X. Effect of double aging on mechanical properties and microstructure of EV31A alloy. Trans. Nonferr. Met. Soc. China 2021, 31, 2606–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zander, D.; Jiang, B.; Huang, Y.; Gavras, S.; Kainer, K.U.; Dieringa, H. Effects of heat treatment on the microstructural evolution and creep resistance of Elektron21 alloy and its nanocomposite. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 789, 139669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Feng, Z.J.; Huang, J.F.; Du, X.D.; An, R.S.; Wang, F.; Lou, Y.C. Influence of a low-frequency alternating magnetic field on hot tearing susceptibility of EV31 magnesium alloy. China Foundry 2021, 18, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiełbus, A. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Elektron 21 alloy after heat treatment. J. Achiev. Mater. Manuf. Eng. 2007, 20, 127–130. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, K.; Hiraga, K. The Structures of Precipitates in an Mg-0.5 at%Nd Age-Hardened Alloy Studied by HAADF-STEM Technique. Mater. Trans. 2011, 52, 1860–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.Y.; Wu, Y.J.; Deng, Q.C.; Ding, C.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, N.X.; Jia, L.C.; Chang, Z.Y.; Peng, L.M. Effect of Gd content on microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg-xGd-Zr alloys via semicontinuous casting. J. Magnes. Alloys, 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.C.; Wen, H.B.; Sun, J.L.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.H.; Liu, B.; Chen, H.W.; Hu, B.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Quantitative exploration of aging–precipitate–property relationship in Mg-Gd alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2026, 245, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.J.; Yang, G.Y.; Luo, S.F.; Jie, W.Q. Microstructure evolution during heat treatment and mechanical properties of Mg–2.49Nd–1.82Gd–0.19Zn–0.4Zr cast alloy. Mater. Charact. 2015, 107, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.L.; Sun, Y.S.; Xue, F.; Xue, S.; Xiao, Y.Y.; Tao, W.J. Creep behavior of Mg–2wt.%Nd binary alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2009, 524, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.D.; Wang, Q.D.; Gao, Y.; Chen, C.J.; Zheng, J. Effects of heat treatments on microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg–11Y–5Gd–2Zn–0.5Zr (wt.%) alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 1696–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nd | Gd | Zn | Zr | Mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.21 | 2.52 | 0.37 | 0.49 | Bal. |

| Serial Number | Temperature/°C | Time/h |

|---|---|---|

| a | 510 | 6 |

| b | 510 | 10 |

| c | 510 | 14 |

| d | 520 | 6 |

| e | 520 | 10 |

| f | 520 | 14 |

| g | 530 | 6 |

| h | 530 | 10 |

| i | 530 | 14 |

| Experimental Alloy | Testing Temperature | UTS (MPa) | YS (MPa) | EL (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| As-cast | Room temperature | 210 ± 12.0 | 117 ± 3.0 | 14.5% ± 4.5 |

| T6-treated | Room temperature | 322 ± 2.0 | 220 ± 23.0 | 8.7% ± 0.2 |

| As-cast | 150 °C | 207 ± 6.5 | 114 ± 8.3 | 27% ± 2.1 |

| T6-treated | 150 °C | 292 ± 2.6 | 185 ± 1.1 | 16% ± 1.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Cui, J.; Liu, H.; Mu, T.; An, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Ye, X. Effect of Heat Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Mg-3.2Nd-2.5Gd-0.4Zn-0.5Zr (wt.%) Alloy. Materials 2025, 18, 5454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235454

Li Y, Cui J, Liu H, Mu T, An L, Zhang Y, Yu Q, Zhang H, Ye X. Effect of Heat Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Mg-3.2Nd-2.5Gd-0.4Zn-0.5Zr (wt.%) Alloy. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235454

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yao, Jingya Cui, Honghui Liu, Tong Mu, Lingyun An, Yongcai Zhang, Qiang Yu, Hailong Zhang, and Xiushen Ye. 2025. "Effect of Heat Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Mg-3.2Nd-2.5Gd-0.4Zn-0.5Zr (wt.%) Alloy" Materials 18, no. 23: 5454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235454

APA StyleLi, Y., Cui, J., Liu, H., Mu, T., An, L., Zhang, Y., Yu, Q., Zhang, H., & Ye, X. (2025). Effect of Heat Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Mg-3.2Nd-2.5Gd-0.4Zn-0.5Zr (wt.%) Alloy. Materials, 18(23), 5454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235454