Unveiling GaN Prismatic Edge Dislocations at the Atomic Scale via P-N Theory Combined with DFT

Abstract

1. Introduction

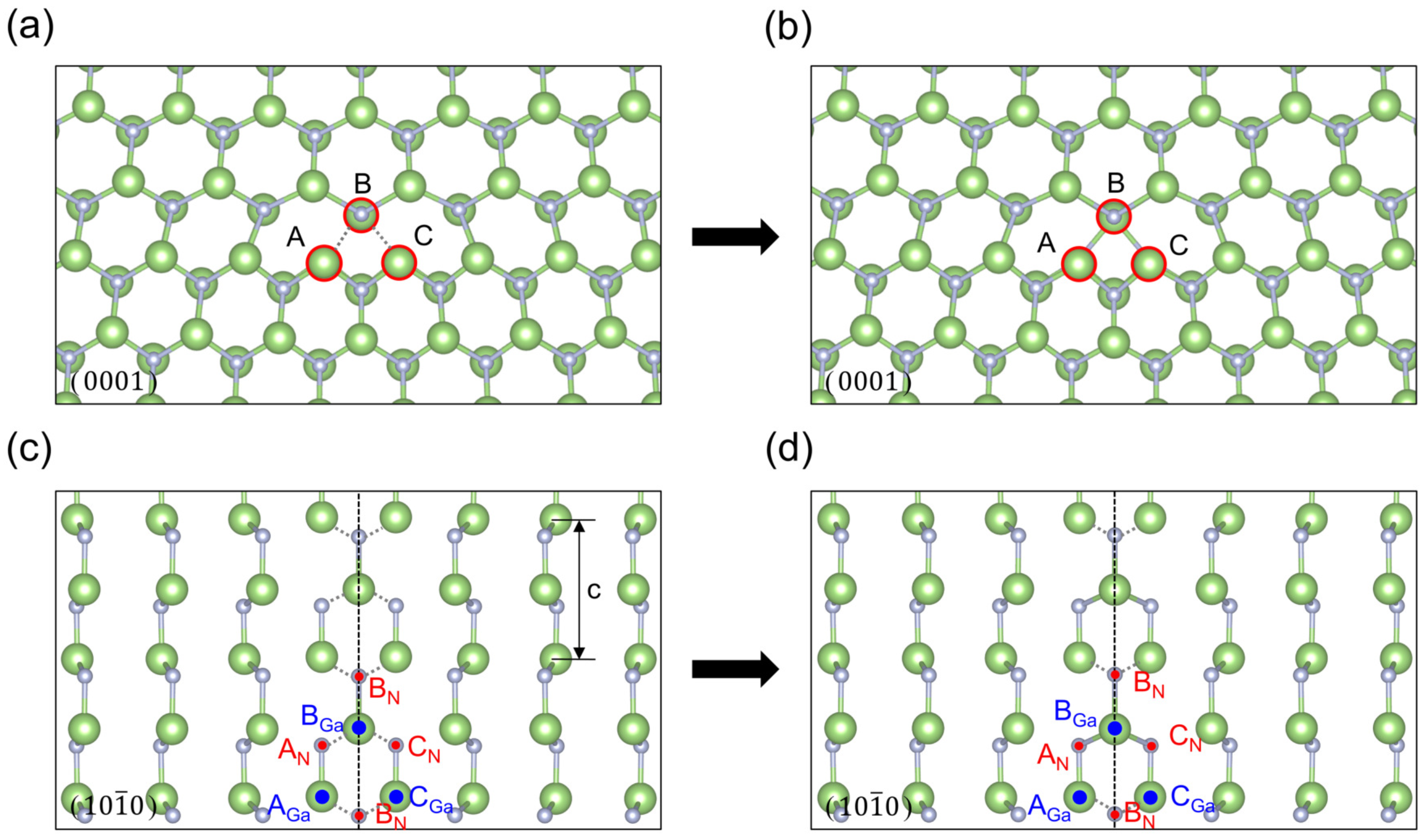

2. The Edge Dislocation Core Structures

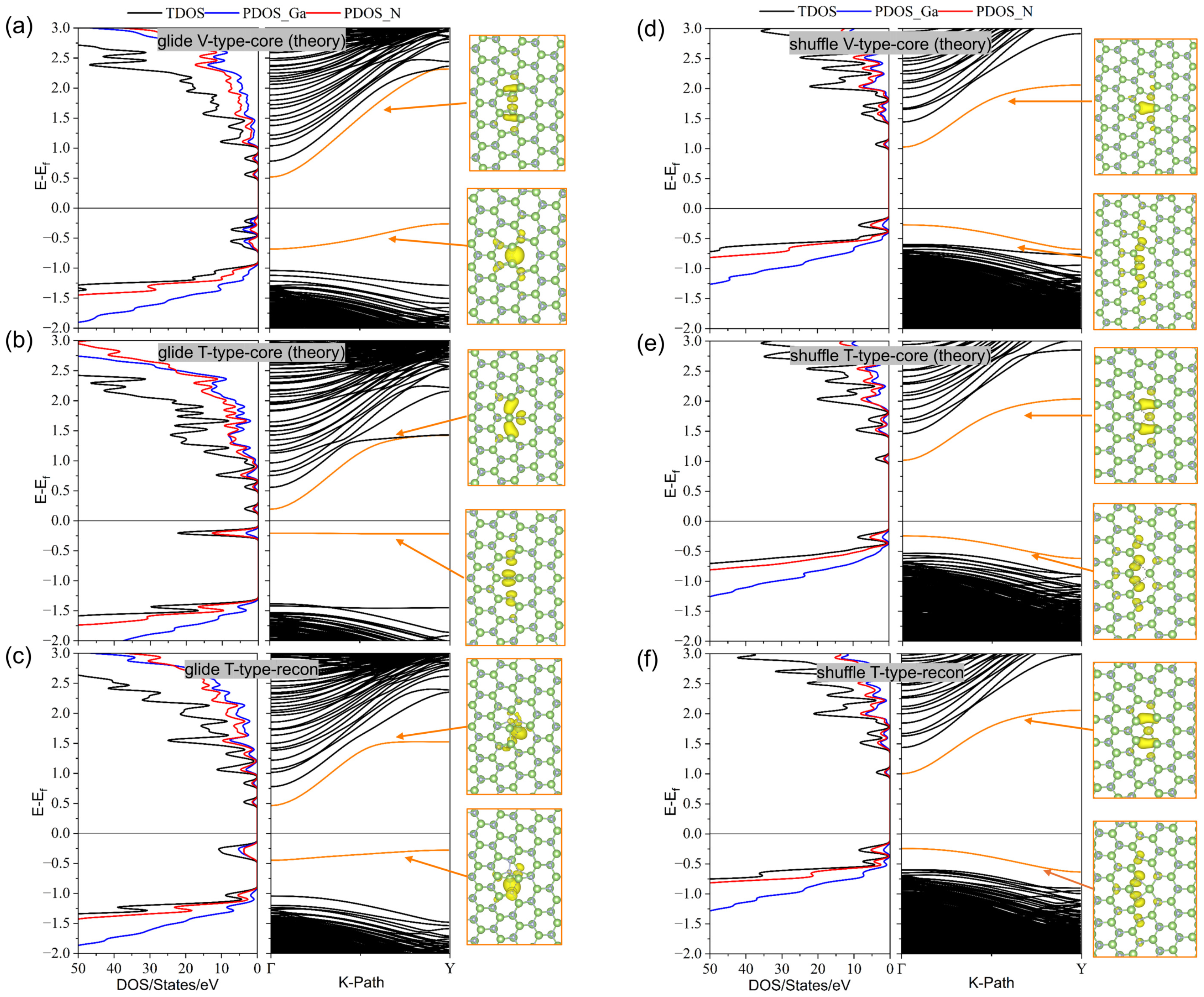

3. The Electronic Properties of Core Structures

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Fully Discrete Peierls Theory

Appendix A.1. The γ-Potential of (1010) Slip Plane

| glide | 0.980 | 0.801 | 0.805 | 0.841 | 0.739 | 0.997 | 1.098 | 1.189 | 0 | 0.567 | 0.682 | 0.757 | 0.980 | 0.954 | 0.978 | 1.027 |

| shuffle | 0.238 | 0.209 | 0.175 | 0.126 | 3.122 | 2.623 | 2.435 | 2.346 | 0 | −0.017 | 0.021 | 0.124 | 0.238 | 0.273 | 0.278 | 0.271 |

Appendix A.2. The Relevant Parameters of the Dislocation Equation

| E (eV/Å) | (eV/Å) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| glide | V-type | 0 | 0.783 | 0.137 | 0.518 | 0.294 | 0.352 | 1.475 | 0.016 | |

| T-type | 1 | 0.886 | 0.220 | 0.573 | 0.360 | 0.573 | 1.491 | |||

| shuffle | V-type | 0 | 0 | - | 0.712 | - | 0.629 | 0.753 | 0.058 | |

| T-type | 1 | 0.360 | - | 1.113 | - | 1.113 | 0.811 |

Appendix A.3. Energy of the Dislocation Core Structures

| (eV/Å) | (eV/Å) | (eV/Å) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| glide | theory | - | −650.736 | 0.379 |

| recore | −651.115 | −650.880 | 0.234 | |

| shuffle | theory | −653.247 | −653.178 | 0.069 |

| recore | - | −653.243 | 0.005 |

| This Work | Ref. [3] | Ref. [43] | Ref. [44] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| theory | glide-set | 0.005 (0.741) | 0.0013 (0.2) | 0.001 (0.15) | 0.001 (0.1528) |

| shuffle-set | 0.017 (2.790) | ||||

| DFT | glide-set | 0.113 (18.066) | - | - | - |

| 0.070 (11.175) | |||||

| shuffle-set | 0.021 (3.301) | - | - | - | |

| 0.001 (0.217) | |||||

| experiment | - | 0.0014 (0.23) | 0.072 (11.5) * | - | |

Appendix A.4. The Bond Angles of the Dislocation Core Structure of the Shuffle Set

| A | B | C | D1 | D2 | E | F | G | H1 | H2 | I | J | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ga | shuffle V-theory (°) | 95.164 | 99.480 | 129.417 | D = 120.743 | 130.245 | 99.113 | 94.772 | H = 105.145 | - | - | ||

| shuffle T-theory (°) | 98.570 | 99.064 | 124.868 | 114.633 | 114.633 | 124.868 | 99.064 | 98.570 | 98.649 | 98.649 | 113.031 | 93.847 | |

| shuffle T-recon (°) | 100.902 | 100.166 | 122.813 | 114.883 | 114.833 | 122.813 | 100.166 | 100.902 | 98.229 | 98.229 | 109.897 | 88.841 | |

| N | shuffle V-theory (°) | 95.709 | 96.861 | 126.929 | D = 122.440 | 127.627 | 96.306 | 95.258 | H = 100.936 | - | - | ||

| shuffle T-theory (°) | 98.224 | 97.965 | 123.815 | 116.738 | 116.738 | 123.815 | 97.965 | 98.224 | 97.427 | 97.427 | 110.859 | 95.715 | |

| shuffle T-recon (°) | 100.885 | 99.030 | 121.785 | 116.876 | 116.876 | 121.785 | 99.030 | 100.885 | 97.557 | 97.557 | 109.550 | 88.066 | |

Appendix A.5. The Electronic DOS and Energy Band of an Ideal Supercell and the Projected DOS of the Dislocation Core Structures

References

- Wang, Z.; Saito, M.; McKenna, K.P.; Ikuhara, Y. Polymorphism of dislocation core structures at the atomic scale. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, H.; Baines, Y.; Beam, E.; Borga, M.; Bouchet, T.; Chalker, P.R.; Charles, M.; Chen, K.J.; Chowdhury, N.; Chu, R.; et al. The 2018 GaN power electronics roadmap. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 2018, 51, 163001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Xue, M.; Chen, R.; Dong, X.; Gao, X.; Wang, J.; Han, S.; Song, W.; Xu, K. Dislocation evolution in anisotropic deformation of GaN under nanoindentation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2024, 125, 142101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Fan, M.; Wang, L.W. First principles calculations of carrier dynamics of screw dislocation. npj Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizilyalli, I.C.; Bui-Quang, P.; Disney, D.; Bhatia, H.; Aktas, O. Reliability studies of vertical GaN devices based on bulk gan substrates. Microelectron. Reliab. 2015, 55, 1654–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Zhang, R.; Kozak, J.P.; Liu, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y. Robustness of cascode GaN hemts in unclamped inductive switching. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 4148–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, J.P.; Zhang, R.; Porter, M.; Song, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, B.; Wang, R.; Saito, W.; Zhang, Y. Stability reliability and robustness of GaN power devices: A review. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 8442–8471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Liu, J.; Yang, K.; Liang, M.; Yi, X.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; et al. Atomic evolution mechanism and suppression of edge threading dislocations in nitride remote heteroepitaxy. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 7458–7466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsner, J.; Jones, R.; Sitch, P.K.; Porezag, V.D.; Elstner, M.; Frauenheim, T.; Heggie, M.I.; Öberg, S.; Briddon, P.R. Theory of threading edge and screw dislocations in GaN. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 79, 3672–3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belabbas, I.; Chen, J.; Nouet, G. Electronic structure and metallization effects at threading dislocation cores in GaN. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2014, 90, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, T.; Chokawa, K.; Araidai, M.; Shiraishi, K.; Oshiyama, A.; Kusaba, A.; Kangawa, Y.; Tanaka, A.; Honda, Y.; Amano, H. Electronic structure analysis of core structures of threading dislocations in GaN. In Proceedings of the Compound Semicomductor Week, Nara, Japan, 19–23 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yakimov, E.B.; Polyakov, A.Y.; Lee, I.H.; Pearton, S.J. Recombination properties of dislocations in GaN. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 123, 161543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, P.H.; Jens, L. Theory of Dislocations, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, Y.; Pennycook, S.J.; Browning, N.D.; Nellist, P.D.; Sivananthan, S.; Omnes, F.; Beaumont, B.; Faurie, J.P.; Gibart, P. Direct observation of the core structures of threading dislocations in GaN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1998, 72, 2680–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béré, A.; Serra, A. Atomic structure of dislocation cores in GaN. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 65, 205323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béré, A.; Serra, A. Structure of [0001] tilt boundaries in GaN obtained by simulation with empirical potentials. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 66, 085330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, I.; Browning, N.D. Intrinsic electronic structure of threading dislocations in GaN. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 65, 075310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lymperakis, L.; Neugebauer, J.; Albrecht, M.; Remmele, T.; Strunk, H.P. Strain induced deep electronic states around threading dislocations in GaN. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93, 196401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belabbas, I.; Ruterana, P.; Chen, J.; Nouet, G. The atomic and electronic structure of dislocations in ga-based nitride semiconductors. Philos. Mag. 2006, 86, 2241–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gröger, R.; Leconte, L.; Ostapovets, A. Structure and stability of threading edge and screw dislocations in bulk GaN. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2015, 99, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belabbas, I.; Chen, J.; Nouet, G. Electronic structure of threading dislocations in wurtzite GaN. Phys. Status Solidi (c) 2015, 12, 1123–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, T.; Sugimoto, K.; Goubara, S.; Inomoto, R.; Okada, N.; Tadatomo, K. Direct observation of inclined a-type threading dislocation with a-type screw dislocation in GaN. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 121, 185101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termentzidis, K.; Isaiev, M.; Salnikova, A.; Belabbas, I.; Lacroix, D.; Kioseoglou, J. Impact of screw and edge dislocations on the thermal conductivity of individual nanowires and bulk GaN: A molecular dynamics study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 5159–5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Carrete, J.; Mingo, N.; Madsen, G.K. Phonon scattering by dislocations in GaN. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 8175–8181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Meng, F.; Chen, H.; Ou, P.; Lan, G.; Li, B.; Qiu, Q.; Song, J. Vacancy-assisted core transformation and mobility modulation of a-type edge dislocations in wurtzite GaN. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2019, 52, 495301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peierls, R. The size of a dislocation. Proc. Phys. Soc. 1940, 52, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabarro, F.R.N. Dislocations in a simple cubic lattice. Proc. Phys. Soc. 1947, 59, 256–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejček, L. Peierls-nabarro model of planar dislocation cores in b.c.c. crystals. Czech. J. Phys. B 1972, 22, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroupa, F.; Lejček, L. Splitting of dislocations in the peierls-nabarro model. Czech. J. Phys. B 1972, 22, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Huang, L.; Wang, R. The 90° partial dislocation in semiconductor silicon: An investigation from the lattice P-N theory and the first principle calculation. Acta Mater. 2016, 109, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wang, R.; Wang, S. A new reconstruction core of the 30° partial dislocation in silicon. Philos. Mag. 2018, 99, 347–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wang, S. A theoretical investigation of the glide dislocations in the sphalerite ZnS. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 124, 175702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wu, X.; Zou, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, R. Charge induced reconstruction of glide partial dislocations and electronic properties in GaN. Scr. Mater. 2022, 207, 114276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Wu, X.; Liu, R. Theoretical calculation of the dislocation width and Peierls barrier and stress for semiconductor silicon. J. Phys. Condens. Matters 2010, 22, 055801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kresse, G.; Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 47, 558–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 11169–11186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blochl, P.E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 17953–17979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kresse, G.; Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 1758–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868, Erratum in Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Yao, C.-H.; Cao, P.-l. Density-functional study of structural and electronic properties of GaNn (n = 1∼19) clusters. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 035306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northrup, J.E.; Neugebauer, J.; Romano, L.T. Inversion domain and stacking mismatch boundaries in GaN. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, M.; Chiarotti, G.L.; Tosatti, E. Ab initio calculations of structural and electronic properties of gallium solid-state phases. Phys. Rev. B 1995, 52, 9988–9998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujikane, M.; Yokogawa, T.; Nagao, S.; Nowak, R. Nanoindentation study on insight of plasticity related to dislocation density and crystal orientation in GaN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 201901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujikane, M.; Yokogawa, T.; Nagao, S.; Nowak, R. Yield shear stress dependence on nanoindentation strain rate in bulk GaN crystal. Phys. Status Solidi C 2011, 8, 429–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AGa-AN | BGa-BN | CGa-CN | AN-BGa | CN-BGa | AGa-BN | CGa-BN | AGa-CGa | AN-CGa | BN-DN | CN-DGa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| glide T-type | theory (Å) | 1.873 | 1.867 | 1.813 | - | 1.823 | - | 1.833 | 2.940 * | 3.070 * | 2.771 * | 3.346 * |

| recon (Å) | 2.084 | 2.063 | 2.025 | - | 1.946 | - | 1.940 | 2.325 | 2.319 † | 1.523 | 2.063 | |

| (Å) | 0.211 | 0.196 | 0.212 | - | 0.123 | - | 0.107 | −0.615 | −0.751 | −1.248 | −1.283 | |

| shuffle T-type | theory (Å) | 1.933 | 1.981 | 1.933 | 2.274 † | 2.274 † | 2.398 † | 2.398 † | - | - | - | - |

| recon (Å) | 1.942 | 2.067 | 1.942 | 2.195 | 2.195 | 2.317 † | 2.317 † | - | - | - | - | |

| (Å) | 0.009 | 0.095 | 0.009 | −0.079 | −0.079 | −0.081 | −0.081 | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peng, L.; Huang, L.; Chen, S.; Huang, C.; Wang, R.; Li, M. Unveiling GaN Prismatic Edge Dislocations at the Atomic Scale via P-N Theory Combined with DFT. Materials 2025, 18, 5453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235453

Peng L, Huang L, Chen S, Huang C, Wang R, Li M. Unveiling GaN Prismatic Edge Dislocations at the Atomic Scale via P-N Theory Combined with DFT. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235453

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Li, Lili Huang, Shi Chen, Chengjin Huang, Rui Wang, and Mu Li. 2025. "Unveiling GaN Prismatic Edge Dislocations at the Atomic Scale via P-N Theory Combined with DFT" Materials 18, no. 23: 5453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235453

APA StylePeng, L., Huang, L., Chen, S., Huang, C., Wang, R., & Li, M. (2025). Unveiling GaN Prismatic Edge Dislocations at the Atomic Scale via P-N Theory Combined with DFT. Materials, 18(23), 5453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235453