Effects of Solution Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of UNS S32750/F53/1.4410 SDSS (Super Duplex Stainless Steel) Alloy

Abstract

1. Introduction

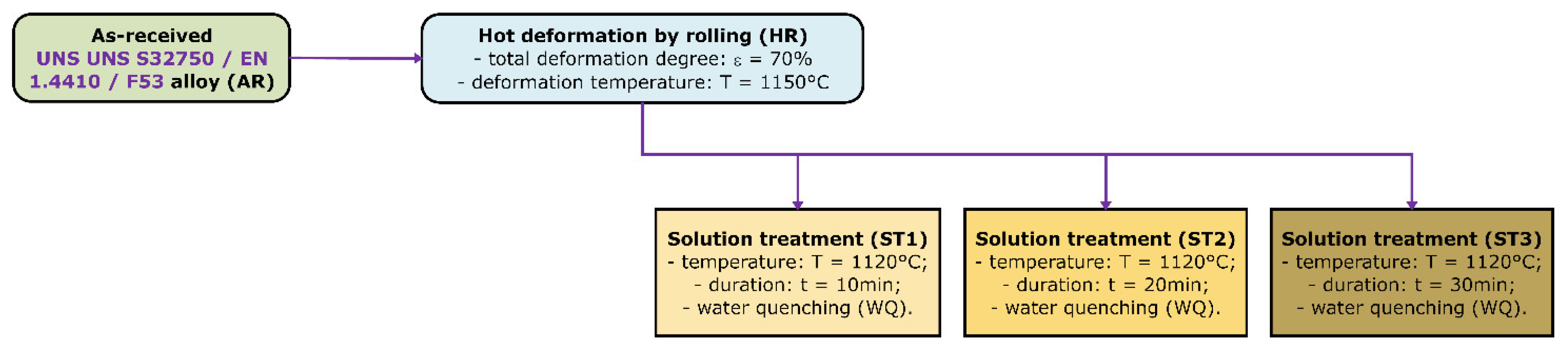

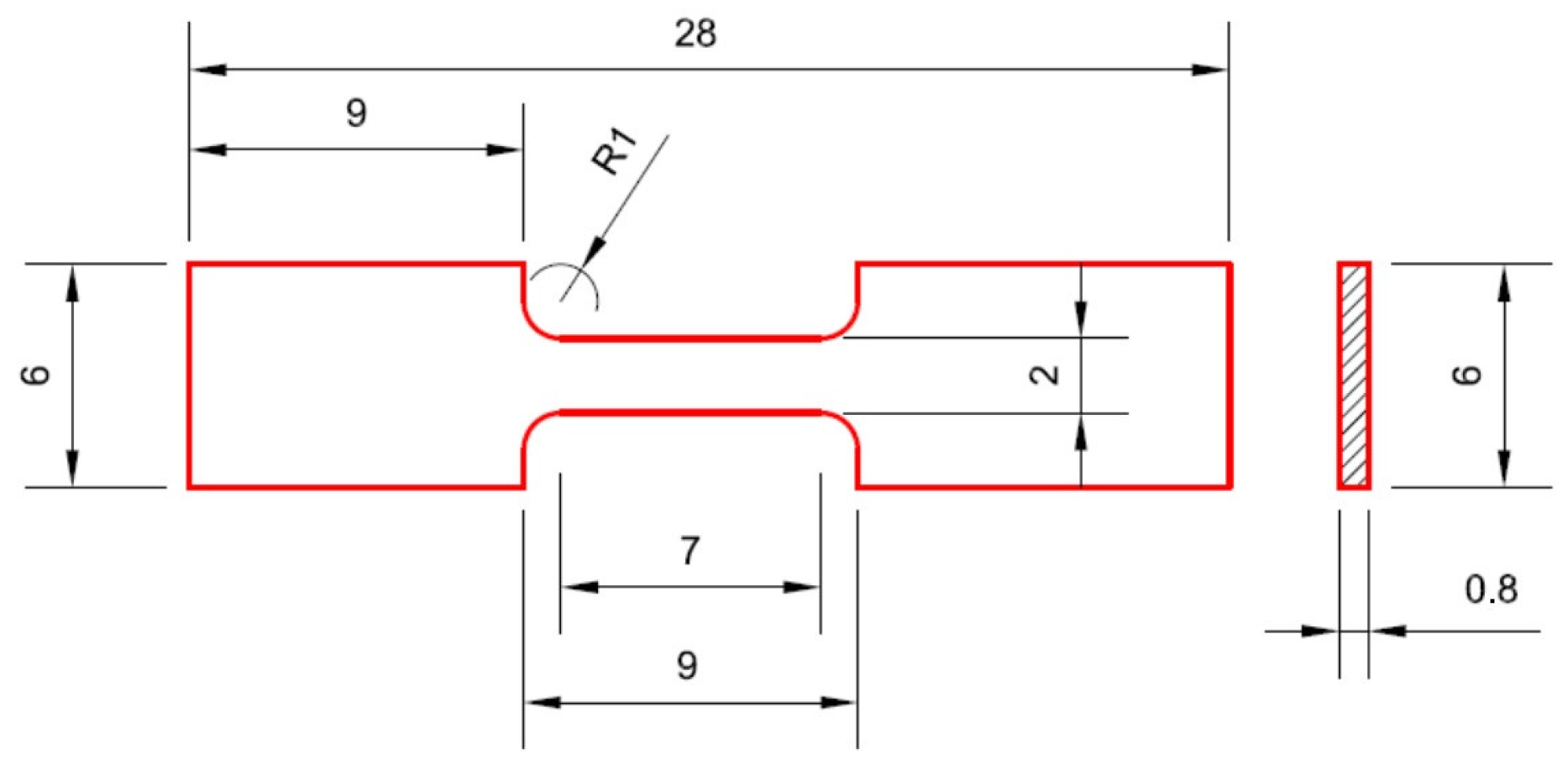

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructural Analysis

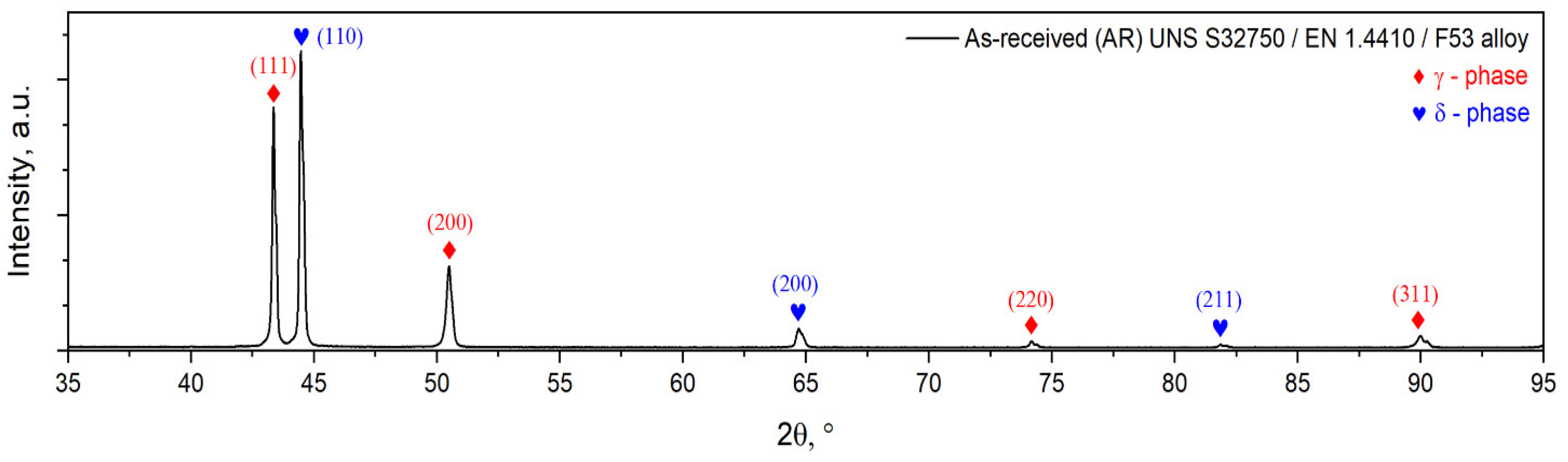

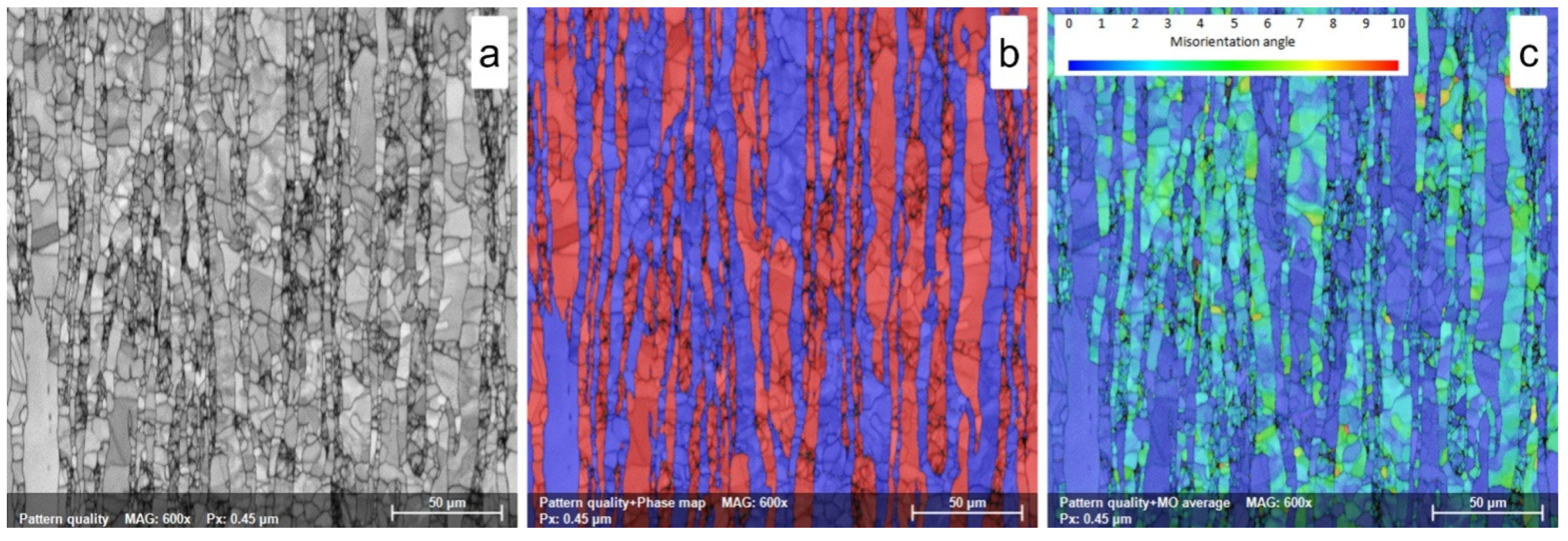

3.1.1. As-Received UNS S32750/EN 1.4410/F53 Super Duplex Stainless Steel (SDSS) Alloy

3.1.2. Hot-Rolled UNS S32750/EN 1.4410/F53 Super Duplex Stainless Steel (SDSS) Alloy

3.1.3. Solution-Treated UNS S32750/EN 1.4410/F53 Super Duplex Stainless Steel (SDSS) Alloy

3.2. Mechanical Analysis

4. Conclusions

- The high soaking temperature and rapid water quenching prevented the formation of the harmful sigma phase, which can form during slow cooling at high temperatures.

- By increasing the duration of the solution treatment (at 1120 °C) from 10 min to 30 min, the following effects were recorded:

- -

- the average grain size of the ferrite phase increased;

- -

- the average grain size of the austenite phase slightly decreased;

- -

- the MO angle of both ferrite and austenite slightly decreased.

- Solution treatment stress-relieves the microstructure by lowering high internal elastic strains and residual stress fields, which are often introduced during processing like hot rolling or additive manufacturing. This process “re-generates” the microstructure by allowing atoms to rearrange. The reduction in residual stress is also a result of the material recovering and recrystallizing, which relieves stresses that build up during mechanical or thermal treatments.

- Increasing solution holding time from 10 min to 30 min improves ductility (εf) while decreasing mechanical strength (σUTS) due to microstructural changes. A longer holding time at the solution annealing temperature of 1120 °C allows for more complete diffusion of alloying elements and the formation of more ferrite.

- The effect of increasing the holding time at the solution annealing temperature of 1120 °C on the mechanical properties can be explained by the increasing percent of ferrite, which is more capable to absorb stress and to prevent stress concentrations, causing more grains to be involved in the plastic deformation process.

- The high yield strength of solution-treated UNS S32750/F53 super duplex stainless steel (≥550 MPa) and tensile strength (≥760 MPa) enable the use of thinner sections, while its good ductility (≥15–25% elongation) means it can be worked similarly to austenitic stainless steels.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nilsson, J.O. Super duplex stainless steels. Mater. Sci. Technol. 1992, 8, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, I.N.; Tavares, S.S.M.; Dalard, F.; Nogueira, R.P. Effect of microstructure on corrosion behavior of super duplex stainless steel at critical environment conditions. Scr. Mater. 2007, 57, 913–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Armas, I. Duplex Stainless Steels: Brief History and Some Recent Alloys. Recent Pat. Mech. Eng. 2008, 1, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levkov, L.; Shurygin, D.; Dub, V.; Kosyrev, K.; Balikoev, A. New generation of super duplex steels for equipment gas and oil production. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 121, 04007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alturaihi, S.S.; Serban, N.; Cinca, I.; Angelescu, M.L.; Balkan, I.V. Influence of solution treatment temperature on microstructural and mechanical properties of hot rolled UNS S32760/F55 super duplex stainless steel (SDSS). U.P.B. Sci. Bull. Ser. B 2021, 83. Available online: https://www.scientificbulletin.upb.ro/rev_docs_arhiva/rez2ab_839863.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Francis, R.; Byrne, G. Duplex Stainless Steels—Alloys for the 21st Century. Metals 2021, 11, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.M.; Dedavid, B.A.; Santos, C.A.; Lopes, N.F.; Fraccaro, C.; Pagartanidis, T.; Lovatto, L.P. Crevice corrosion on stainless steels in oil and gas industry: A review of techniques for evaluation, critical environmental factors and dissolved oxygen. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 144, 106955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Agrawal, A.; Mandal, A.; Podder, A.S. Characteristics and Manufacturability of Duplex Stainless Steel: A Review. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2021, 74, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, P.; Wins, K.L.D.; Dhas, D.E.J.; George, P. Machinability, weldability and surface treatment studies of SDSS 2507 material—A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 7682–7687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, J. Super Duplex Stainless Steels: Structure and Properties. In Proceedings of the Duplex Stainless Steels Conference, Les Ulis Cedex, France, 28–30 October 1991; Les Editions de Physique: Les Ulis Cedex, France, 1991; Volume 1, pp. 3–48. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Wang, K.; Lei, Y. Effects of Nitrogen on Microstructure and Properties of SDSS 2507 Weld Joints by Gas Focusing Plasma Arc Welding. Materials 2024, 17, 5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, R.N. Duplex Stainless Steels, Microstructure, Properties and Applications; Woodhead Publishing Ltd.: Cambridge, UK, 1997; pp. 1–204. Available online: https://download.e-bookshelf.de/download/0000/7504/61/L-G-0000750461-0002366929.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Chail, G.; Kangas, P. Super and Hyper Duplex Stainless Steels: Structures, Properties and Applications. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2016, 2, 1755–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, A.Y.; Diwakar, N.; Kalpande, S.D. Impact of high temperature heat input on morphology and mechanical properties of duplex stainless steel 2205. U.P.B. Sci. Bull. Ser. D 2023, 85. Available online: https://www.scientificbulletin.upb.ro/rev_docs_arhiva/rezdb6_916934.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Maki, T.; Furuhara, T.; Tsuzaki, K. Microstructure development by thermomechanical processing in duplex stainless steel. ISIJ Int. 2001, 41, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojocaru, V.D.; Șerban, N.; Cojocaru, E.M.; Zărnescu-Ivan, N. High-Temperature Deformation Behaviour of UNS S32750 Super Duplex Stainless Steel (SDSS) Alloy. Materials 2024, 17, 5151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilha, A.F.; Plaut, R.L.; Rios, P.R. Stainless Steels Heat Treatment (Chapter 12), Totten GE. In Steel Heat Treatment Handbook, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 695–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, K.; Lei, Y. A Review of Welding Process for UNS S32750 Super Duplex Stainless Steel. Materials 2024, 17, 5215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alturaihi, S.S.; Alluaibi, M.H.; Cojocaru, E.M.; Raducanu, D. Microstructural changes occurred during hot-deformation of SDSS F55 (super-duplex stainless steel) alloy. U.P.B. Sci. Bull. Ser. B 2019, 81. Available online: https://www.scientificbulletin.upb.ro/rev_docs_arhiva/full74c_462419.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Gregori, A.; Nilsson, J.O. Decomposition of ferrite in commercial superduplex stainless steel weld metals; Microstructural transformations above 700 °C. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2002, 33, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, B.R.; Miranda, A.; Gonzalez, D.; Praga, R.; Hurtado, E. Maintenance of the Austenite/Ferrite Ratio Balance in GTAW DSS Joints Through Process Parameters Optimization. Materials 2020, 13, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TMR Stainless. Practical Guidelines for the Fabrication of Duplex Stainless Steels, 3rd ed.; International Molybdenum: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-907470-09-7. [Google Scholar]

- Knyazeva, M.; Pohl, M. Duplex Steels: Part I: Genesis, Formation, Structure. Metallogr. Microstruct. Anal. 2013, 2, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzato, L.; Calliari, I. Advances in Duplex Stainless Steels. Materials 2022, 15, 7132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J.O.; Wilson, A. Influence of isothermal phase transformations on toughness and pitting corrosion of super duplex stainless steel SAF 2507. Mater. Sci. Technol. 1993, 9, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Kim, K.T.; Lee, Y.D.; Lee, C.S. Effect of Heat Treatment on Mechanical Properties of Super Duplex Stainless Steel. Adv. Mater. Res. 2010, 89–91, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, V.A.; Hurtig, K.; Eyzop, D.; Östberg, A.; Janiak, P.; Karlsson, L. Ferrite content measurement in super duplex stainless steel welds. Weld. World 2018, 63, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulraj, P.; Garg, R. Effect of Intermetallic Phases on Corrosion Behavior and Mechanical Properties of Duplex Stainless Steel and Super-Duplex Stainless Steel. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2015, 9, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W.; Tjong, S.C. Effect of Secondary Phase Precipitation on the Corrosion Behavior of Duplex Stainless Steels. Materials 2014, 7, 5268–5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitacco, E.; Bertolini, R.; Ghinatti, E.; Pezzato, L.; Gennari, C.; Calliari, I.; Pigato, M. Effect of open die forging and cooling rate on the precipitation of secondary phases and corrosion properties of a cast UNS S32760 super duplex stainless steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 9992–10002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calliari, I.; Brunelli, K.; Dabala, M.; Ramous, E. Measuring secondary phases in duplex stainless steels. J. Mater. 2009, 61, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Chung, W.; Shin, B.-H. Effects of the Volume Fraction of the Secondary Phase after Solution Annealing on Electrochemical Properties of Super Duplex Stainless Steel UNS S32750. Metals 2023, 13, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, B.-H.; Kim, D.; Park, S.; Hwang, M.; Chung, W. Precipitation condition and effect of volume fraction on corrosion properties of secondary phase on casted super-duplex stainless steel UNS S32750. Anti-Corros. Methods Mater. 2019, 66, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J.O.; Kangas, P.; Karlsson, T.; Wilson, A. Mechanical properties, microstructural stability and kinetics of σ-phase formation in 29Cr-6Ni-2Mo-0.38N superduplex stainless steel. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2000, 31, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorca-Isern, N.; López-Luque, H.; López-Jiménez, I.; Biezma, M.V. Identification of sigma and chi phases in duplex stainless steels. Mater. Charact. 2016, 112, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escriba, D.M.; Materna-Morris, E.; Plaut, R.L.; Padilha, A.F. Chi-phase precipitation in a duplex stainless steel. Mater. Charact. 2009, 60, 1214–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, A.J.; Lippold, J.C.; Brandi, S.D. The relationship between chromium nitride and secondary austenite precipitation in duplex stainless steels. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2003, 34, 1575–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, A.J.; Brandi, S.D.; Lippold, J.C. Secondary austenite and chromium nitride precipitation in simulated heat afected zones of duplex stainless steels. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2004, 9, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Shi, H.Q.; Ma, L.Q.; Ding, Y. The Analysis and Research of Secondary Phases Generated during Isothermal Aging of Duplex Stainless Steels. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 193–194, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwic, P.D.; Honeycomb, R.W.K. Precipitation of M23C6 at austenite/ferrite interfaces in duplex stainless steel. Met. Sci. 1982, 16, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.U.; Rho, B.S.; Nam, S.W. Correlation of the M23C6 precipitation morphology with grain boundary characteristics in austenitic stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2001, 318, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.K.; Wang, C.H.; Wang, K.C.; Chen, K.K. TEM analysis of 2205 duplex stainless steel to determine orientation relationship between M23C6 carbide and austenite matrix at 950 °C. Intemetallics 2014, 45, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maetz, J.Y.; Douillard, T.; Cazottes, S.; Verdu, C.; Kléber, X. M23C6 carbides and Cr2N nitrides in aged duplex stainless steel: A SEM, TEM and FIB tomography investigation. Micron 2016, 84, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Oh, C.S.; Han, H.N.; Lee, C.G.; Kim, S.J.; Takaki, S. On the crystal structure of Cr2N precipitates in high-nitrogen austenitic stainless steel. Acta Crystallogr. B 2005, 61, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. Precipitation of sigma phase in duplex stainless steel and recent development on its detection by electrochemical potentiokinetic reactivation: A review. Corros. Commun. 2021, 2, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BasYigit, A.B.; Kurt, A. Effects of sigma phase on corrosion resistance in duplex stainless steels. Int. J. Eng. Res. Dev. 2015, 7, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, V.A.; Karlsson, L.; Wessman, S.; Fuertes, N. Effect of Sigma Phase Morphology on the Degradation of Properties in a Super Duplex Stainless Steel. Materials 2018, 11, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, P.; Xie, J.; Jiang, Y.; Tang, P.; Liang, B.; Lu, Y.; Gong, J. Mechanical Properties of σ-Phase and Its Effect on the Mechanical Properties of Austenitic Stainless Steel. Coatings 2022, 12, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.C.; Wu, W. Overview of Intermetallic Sigma (σ) Phase Precipitation in Stainless Steels. ISRN Metall. 2012, 2012, 732471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodžić, A.; Gigović-Gekić, A.; Sunulahpašić, R. Sigma phase precipitation in austenitic stainless steels. In Proceedings of the13th Scientific/Research Symposium with International Participation “Metallic and Nonmetallic Materials”, Zenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 27 May 2021; Available online: https://mnm.unze.ba/article/58/pdf (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Villanueva, D.M.E.; Junior, F.C.P.; Plaut, R.L.; Padilha, A.F. Comparative study on sigma phase precipitation of three types of stainless steels: Austenitic, superferritic and duplex. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2006, 22, 1098–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, V.A.; Karlsson, L.; Engelberg, D.; Wessman, S. Time-temperature-precipitation and property diagrams for super duplex stainless steel weld metals. Weld. World 2018, 62, 517–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Jiang, Y.; Deng, B.; Sun, T.; Xu, J.; Li, J. Effect of annealing temperature on the pitting corrosion resistance of super duplex stainless steel UNS S32750. Mater. Charact. 2009, 60, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervo, R.; Ferro, P.; Tiziani, A. Annealing temperature effects on super duplex stainless steel UNS S32750 welded joints. I: Microstructure and partitioning of elements. J. Mater. Sci. 2010, 45, 4369–4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Wang, F.; Yang, Z.; Sun, L.; Li, Y.; Jin, J. Effect of Ferrite Proportion and Precipitates on Dual-Phase Corrosion of S32750 Super Duplex Stainless Steel with Different Annealing Temperatures. Steel Res. Int. 2021, 92, 2000568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fargas, G.; Anglada, M.; Mateo, A. Effect of the annealing temperature on the mechanical properties, formability, and corrosion resistance of hot-rolled duplex stainless steel. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2009, 209, 1770–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojocaru, V.D.; Șerban, N.; Angelescu, M.L.; Cotruț, M.C.; Cojocaru, E.M.; Vintilă, A.N. Influence of Solution Treatment Temperature on Microstructural Properties of an Industrially Forged UNS S32750/1.4410/F53 Super Duplex Stainless Steel (SDSS) Alloy. Metals 2017, 7, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelescu, M.L.; Cojocaru, E.M.; Șerban, N.; Cojocaru, V.D. Evaluation of Hot Deformation Behaviour of UNS S32750 Super Duplex Stainless Steel (SDSS) Alloy. Metals 2020, 10, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojocaru, E.M.; Nocivin, A.; Răducanu, D.; Angelescu, M.L.; Cinca, I.; Balkan, I.V.; Șerban, N.; Cojocaru, V.D. Microstructure Evolution during Hot Deformation of UNS S32750 Super-Duplex Stainless Steel Alloy. Materials 2021, 14, 3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojocaru, E.M.; Raducanu, D.; Nocivin, A.; Cinca, I.; Vintila, A.N.; Serban, N.; Angelescu, M.L.; Cojocaru, V.D. Influence of Aging Treatment on Microstructure and Tensile Properties of a Hot Deformed UNS S32750 Super Duplex Stainless Steel (SDSS) Alloy. Metals 2020, 10, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, F.M., Jr.; da Silva, L.O.P.; dos Santos, Y.T.B.; Callegari, B.; Lima, T.N.; Coelho, R.S. Microstructural and Electrochemical Analysis of the Physically Simulated Heat-Affected Zone of Super-Duplex Stainless Steel UNS S32750. Metals 2025, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaya, M. Characterization of microstructural damage due to low-cycle-fatigue by EBSD observation. Mater. Charact. 2009, 60, 1454–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.I.; Nowell, M.M.; Field, D.P. A review of strain analysis using electron backscatter diffraction. Microsc. Microanal. 2011, 17, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaya, M. Assessment of local deformation using EBSD: Quantification of local damage at grain boundaries. Mater. Charact. 2012, 66, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelescu, M.L.; Dan, A.; Ungureanu, E.; Zarnescu-Ivan, N.; Galbinasu, B.M. Effects of Cold Rolling Deformation and Solution Treatment on Microstructural, Mechanical, and Corrosion Properties of a Biocompatible Ti-Nb-Ta-Zr Alloy. Metals 2022, 12, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ferrite (δ-Phase) | Austenite (γ-Phase) | |

|---|---|---|

| XRD measurements: | ||

| - Lattice parameter, a [Å] | 2.88(1) | 3.61(5) |

| - Lattice micro-strain, ε [%] | 0.03(6) | 0.03(7) |

| EBSD measurements: | ||

| - Weight fraction, [%wt.] | 55.1 ± 0.9 | 44.9 ± 0.9 |

| - Average grain size, D [μm] | 14.2 ± 1.3 | 6.9 ± 1.9 |

| - Max. misorientation, [°] | 9.1 ± 0.7 | 6.2 ± 0.5 |

| Ferrite (δ-Phase) | Austenite (γ-Phase) | |

|---|---|---|

| XRD measurements: | ||

| - Lattice parameter, a [Å] | 2.88(6) | 3.61(9) |

| - Lattice micro-strain, ε [%] | 0.11(2) | 0.34(2) |

| EBSD measurements: | ||

| - Weight fraction, [%wt.] | 53.5 ± 0.8 | 46.5 ± 0.8 |

| - Average grain size, D [μm] | - | - |

| - Max. misorientation, [°] | 19.1 ± 1.6 | 12.3 ± 1.3 |

| Ferrite (δ-Phase) | Austenite (γ-Phase) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Solution treatment: 1120 °C—10 min—WQ (ST1) | |||

| XRD measurements | Lattice parameter, a [Å] | 2.88 (1) | 3.61 (4) |

| Lattice micro-strain, ε [%] | 0.09 (4) | 0.23 (3) | |

| EBSD measurements | Weight fraction, [%wt.] | 55.6 ± 0.5 | 44.4 ± 0.5 |

| Average grain size, D [μm] | 30.1 ± 0.6 | 18.8 ± 1.1 | |

| Max. misorientation, [°] | 5.6 ± 0.7 | 3.4 ± 1.2 | |

| Solution treatment: 1120 °C—20 min—WQ (ST2) | |||

| XRD measurements | Lattice parameter, a [Å] | 2.87 (3) | 3.61 (3) |

| Lattice micro-strain, ε [%] | 0.08 (1) | 0.23 (8) | |

| EBSD measurements | Weight fraction, [%wt.] | 57.4 ± 0.2 | 42.6 ± 0.2 |

| Average grain size, D [μm] | 31.1 ± 0.7 | 18.5 ± 0.8 | |

| Max. misorientation, [°] | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 3.3 ± 1.5 | |

| Solution treatment: 1120 °C—30 min—WQ (ST3) | |||

| XRD measurements | Lattice parameter, a [Å] | 2.87 (1) | 3.60 (9) |

| Lattice micro-strain, ε [%] | 0.08 (2) | 0.23 (8) | |

| EBSD measurements | Weight fraction, [%wt.] | 58.5 ± 0.2 | 41.5 ± 0.2 |

| Average grain size, D [μm] | 32.2 ± 0.8 | 18.1 ± 1.1 | |

| Max. misorientation, [°] | 5.1 ± 0.8 | 3.3 ± 1.1 | |

| Ultimate Tensile Strength, σUTS [MPa] | Yield Strength, σ0.2 [MPa] | Elongation to Fracture, εf [%] | Absorbed Energy KCV [J] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | >(730–750) | >(530–550) | >25 | >100 |

| ST1 (1120 °C—10 min—WQ) | 786.8 ± 5.2 | 560.6 ± 4.9 | 44.1 ± 1.9 | 132.5 ± 1.9 |

| ST2 (1120 °C—20 min—WQ) | 783.8 ± 2.1 | 573.7 ± 6.7 | 46.7 ± 1.4 | 133.9 ± 2.8 |

| ST3 (1120 °C—30 min—WQ) | 762.5 ± 5.5 | 572.8 ± 3.5 | 48.4 ± 2.4 | 133.2 ± 0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cojocaru, V.D.; Angelescu, M.L.; Șerban, N.; Zărnescu-Ivan, N.; Cojocaru, E.M. Effects of Solution Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of UNS S32750/F53/1.4410 SDSS (Super Duplex Stainless Steel) Alloy. Materials 2025, 18, 5447. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235447

Cojocaru VD, Angelescu ML, Șerban N, Zărnescu-Ivan N, Cojocaru EM. Effects of Solution Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of UNS S32750/F53/1.4410 SDSS (Super Duplex Stainless Steel) Alloy. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5447. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235447

Chicago/Turabian StyleCojocaru, Vasile Dănuț, Mariana Lucia Angelescu, Nicolae Șerban, Nicoleta Zărnescu-Ivan, and Elisabeta Mirela Cojocaru. 2025. "Effects of Solution Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of UNS S32750/F53/1.4410 SDSS (Super Duplex Stainless Steel) Alloy" Materials 18, no. 23: 5447. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235447

APA StyleCojocaru, V. D., Angelescu, M. L., Șerban, N., Zărnescu-Ivan, N., & Cojocaru, E. M. (2025). Effects of Solution Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of UNS S32750/F53/1.4410 SDSS (Super Duplex Stainless Steel) Alloy. Materials, 18(23), 5447. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235447