Effect of Framework Material and Thermal Aging on Shear Bond Strength of Three Different Gingiva-Colored Composite Resins

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Framework Specimens

2.2. Application of Gingiva-Colored Resin Composite

2.2.1. Application of Primer

2.2.2. Application of Gingiva-Colored Opaque

2.2.3. Application of Gingiva-Colored Composite

2.3. Thermal Aging and SBS Test

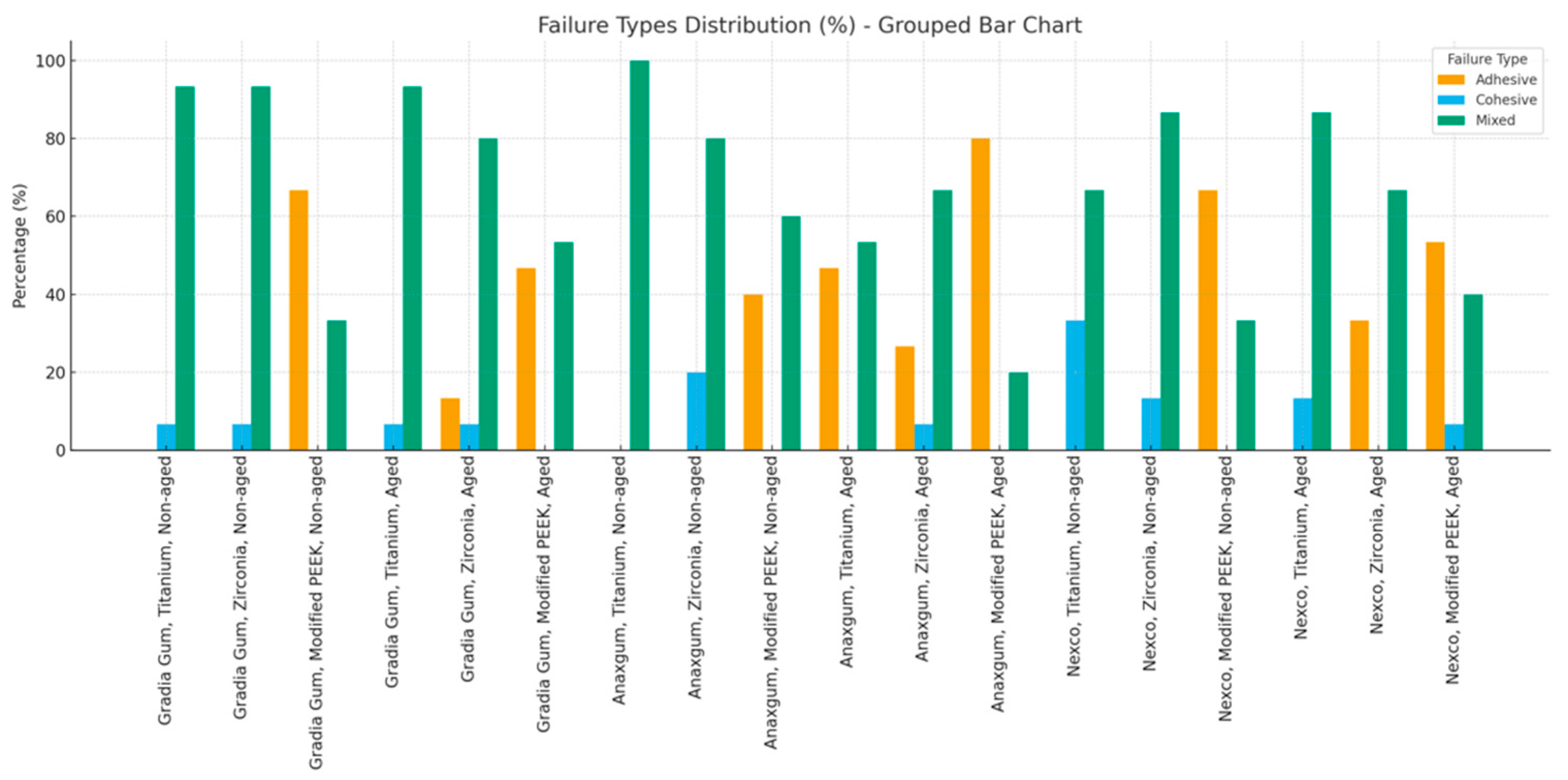

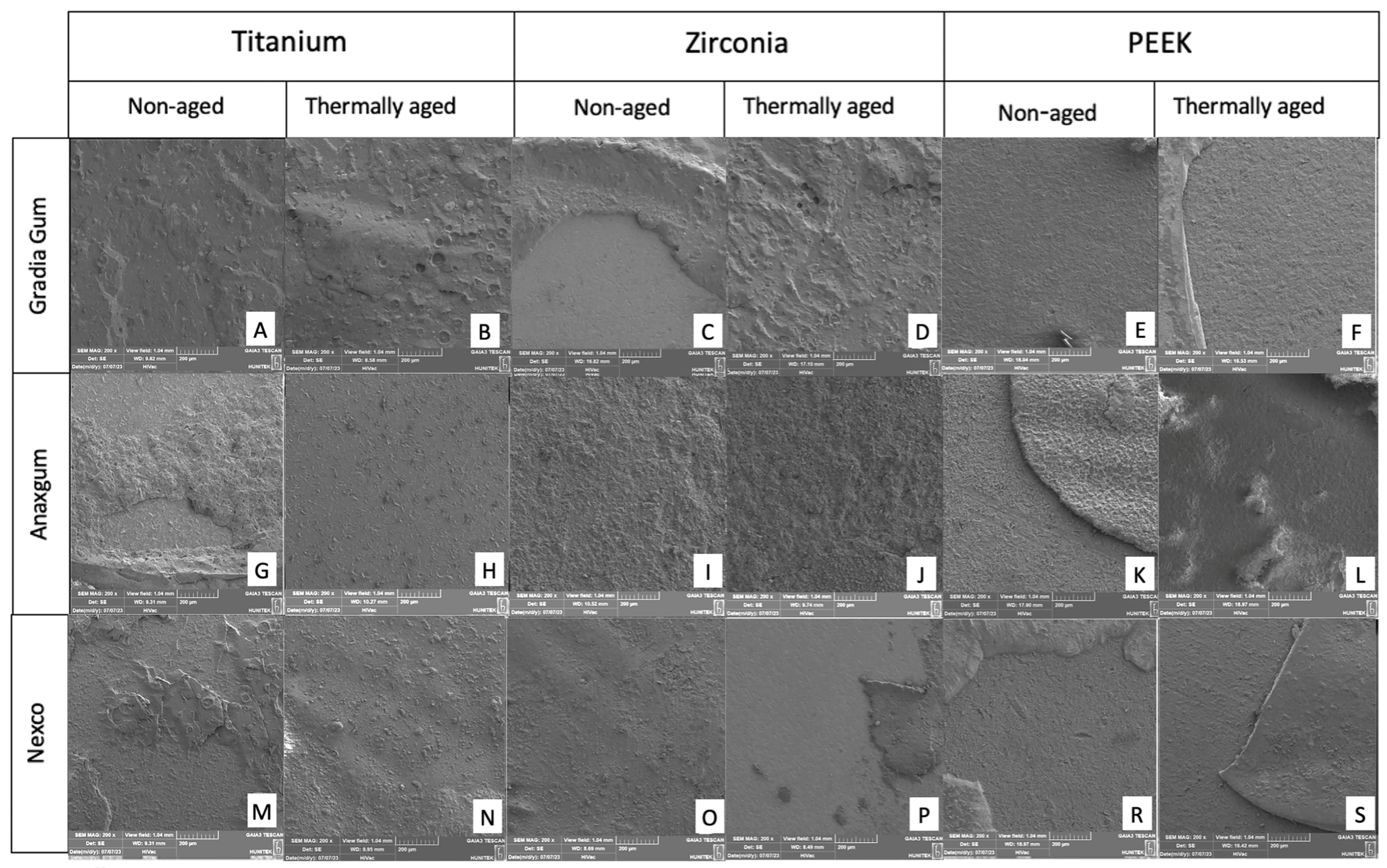

2.4. Analysis of Modes of Failure

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SBS | Shear Bond Strength |

| CAD/CAM | Computer-Aided Design/Computer-Aided Manufacturing |

| PEEK | Polyetheretherketone |

| MPa | Megapascal |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| AF | Adhesive Failure |

| CF | Cohesive Failure |

| MF | Mixed Failure |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

References

- Shamir, R.; Daugela, P.; Juodzbalys, G. Comparison of classifications and indexes for extraction socket and implant supported restoration in the aesthetic zone: A systematic review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Res. 2022, 13, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mareque, S.; Castelo-Baz, P.; López-Malla, J.; Blanco, J.; Nart, J.; Vallés, C. Clinical and esthetic outcomes of immediate implant placement compared to alveolar ridge preservation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 4735–4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miletic, V.; Trifković, B.; Stamenković, D.; Tango, R.N.; Paravina, R.D. Effects of staining and artificial aging on optical properties of gingiva-colored resin-based restorative materials. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 6817–6827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzarug, Y.A.; Galburt, R.B.; Ali, A.; Finkelman, M.; Dam, H.G. An in vitro comparison of the shear bond strengths of two different gingiva-colored materials bonded to commercially pure titanium and acrylic artificial teeth. J. Prosthodont. 2014, 23, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, H.; Takeuchi, Y.; Imai, H.; Kawai, T.; Yoneyama, T. Application of titanium and titanium alloys to fixed dental prostheses. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2019, 63, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeban, Y. Effectiveness of CAD-CAM milled versus DMLS titanium frameworks for hybrid denture prosthesis: A narrative review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, N.C.; Frazier, K.; Bedran-Russo, A.K.; Khajotia, S.; Park, J.; Urquhart, O.; Council on Scientific Affairs. Zirconia restorations: An American Dental Association Clinical Evaluators Panel survey. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2021, 152, 80–81.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lawn, B.R. Novel zirconia materials in dentistry. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.Y.; Teng, M.H.; Wang, Z.J.; Li, X.; Liang, J.Y.; Wang, W.X.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, B.D. Comparative evaluation of BioHPP and titanium as a framework veneered with composite resin for implant-supported fixed dental prostheses. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 122, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çulhaoğlu, A.K.; Özkır, S.E.; Türkkal, F. Polieter eter keton (PEEK) ve dental kullanımı. J. Dent. Fac. Atatürk Uni. 2019, 29, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najeeb, S.; Zafar, M.S.; Khurshid, Z.; Siddiqui, F. Applications of polyetheretherketone (PEEK) in oral implantology and prosthodontics. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2016, 60, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahbi, M.A.; Al Sharief, H.S.; Tayeb, H.; Bokhari, A. Minimally invasive use of coloured composite resin in aesthetic restoration of periodontially involved teeth: Case report. Saudi Dent. J. 2013, 25, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, J.W.; Craig, R.G. Distribution of stresses in porcelain-fused-to-metal and porcelain jacket crowns. J. Dent. Res. 1975, 54, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Real-Osuna, J.; Almendros-Marqués, N.; Gay-Escoda, C. Prevalence of complications after the oral rehabilitation with implant-supported hybrid prostheses. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2012, 17, e116–e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.S.; Park, J.M.; Park, E.J. Evaluation of shear bond strengths of gingiva-colored composite resin to porcelain, metal and zirconia substrates. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2011, 3, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, T.A.; Robaian, A.; Al-Gerny, Y.; Hussein, E.M.R. Influence of surface treatment on repair bond strength of CAD/CAM long-term provisional restorative materials: An in vitro study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aker Sagen, M.; Vos, L.; Dahl, J.E.; Rønold, H.J. Shear bond strength of resin bonded zirconia and lithium disilicate—Effect of surface treatment of ceramics and dentin. Biomater. Investig. Dent. 2022, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bredent GmbH & Co. KG. Presentation of the system. Product Catalog. In The Aesthetic and Functional System: Visio.lign; Bredent GmbH & Co. KG: Senden, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kiomarsi, N.; Yazdizadeh, M.; Khosravi, K.; Najafi, F.; Niazi, E. Effect of thermocycling and surface treatment on repair shear bond strength of composite. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2017, 42, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mourad, A.M. Assessment of bonding effectiveness of adhesive materials to tooth structure using bond strength test methods: A review of literature. Open Dent. J. 2018, 12, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asar, Ö.; Ilk, Ö.; Dağ, Ö. Estimating Box–Cox power transformation parameter via goodness-of-fit tests. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2014, 46, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitta, J.; Branco, T.C.; Portugal, J. Effect of saliva contamination and artificial aging on different primer/cement systems bonded to zirconia. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 119, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczesio-Wlodarczyk, A.; Kopacz, K.; Szynkowska-Jozwik, M.I.; Sokolowski, J.; Bociong, K. An evaluation of the hydrolytic stability of selected experimental dental matrices and composites. Materials 2022, 15, 5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F.C.; Palma-Dibb, R.G.; Campi, L.B.; Roselino, R.F.; Gomes, É.A.; Canevese, V.A.; Pereira, G.K.R.; Spazzin, A.; Sousa-Neto, M. Surface topography and bond strength of CAD–CAM milled zirconia ceramic luted onto human dentin: Effect of surface treatments before and after sintering. Appl. Adhes. Sci. 2018, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulgey, M.; Gorler, O.; Karahan Gunduz, C. Effects of laser modalities on shear bond strengths of composite superstructure to zirconia and PEEK infrastructures: An in vitro study. Odontology 2021, 109, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.K.; Ahn, B. Effect of Al2O3 sandblasting particle size on the surface topography and residual compressive stresses of three different dental zirconia grades. Materials 2021, 14, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopuz, D.; Erçin, Ö.; Sacu, E.; Yersel, G.; Tekçe, N. Effect of primer compositions on the bond strength of resin cement to ceramic materials. Am. J. Dent. 2024, 37, 136–140. [Google Scholar]

- Su, N.; Yue, L.; Liao, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Shen, J. The effect of various sandblasting conditions on surface changes of dental zirconia and shear bond strength between zirconia core and indirect composite resin. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2015, 7, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çulhaoğlu, A.K.; Özkır, S.E.; Şahin, V.; Yılmaz, B.; Kılıçarslan, M.A. Effect of various treatment modalities on surface characteristics and shear bond strengths of polyetheretherketone-based core materials. J. Prosthodont. 2020, 29, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S.; Nikaido, T.; Takahashi, R.; Zhu, L.; Ikeda, M.; Foxton, R.M.; Sadr, A.; Tagami, J. Effect of primer treatment on bonding of resin cements to zirconia ceramic. Dent. Mater. 2010, 26, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koko, M.; Takagaki, T.; Abd El-Sattar, N.E.A.; Tagami, J.; Abdou, A. MDP salts: A new bonding strategy for zirconia. J. Dent. Res. 2022, 101, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğur, M.; Kavut, İ.; Tanrıkut, Ö.O.; Cengiz, Ö. Effect of ceramic primers with different chemical contents on the shear bond strength of CAD/CAM ceramics with resin cement after thermal ageing. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, T.; Koizumi, H.; Hiraba, H.; Hanawa, T.; Matsumura, H.; Yoneyama, T. Effect of luting system with acidic primers on the durability of bonds with Ti-15Mo-5Zr-3Al titanium alloy and its component metals. Dent. Mater. J. 2023, 42, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Yu, J.; Wang, Y.; Tang, C.; Huang, C. Acidic pH weakens the bonding effectiveness of silane contained in universal adhesives. Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erjavec, A.K.; Cresnar, K.P.; Svab, I.; Vuherer, T.; Zigon, M.; Bruncko, M. Determination of shear bond strength between PEEK composites and veneering composites for the production of dental restorations. Materials 2023, 16, 3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubochi, K.; Komine, F.; Fushiki, R.; Yagawa, S.; Mori, S.; Matsumura, H. Shear bond strength of a denture base acrylic resin and gingiva-colored indirect composite material to zirconia ceramics. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2017, 61, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ergün, G.; Tekli, B. Yüksek performanslı polimerlerin bazı dental materyaller ile bağlanma dayanımlarının değerlendirilmesi: Bir derleme. Curr. Res. Dent. Sci. 2022, 32, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.S.; Heo, S.M.; Lee, Y.K.; Kim, C.W. Shear bond strength between titanium alloys and composite resin: Sandblasting versus fluoride-gel treatment. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2003, 64, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, A.; Sahu, S.K.; Dani, A.; Shah, S.; Birajdar, K.; Gaba, T. Evaluation of the effect of different surface treatments on the bonding between PEEK and gingival composite resin: An in vitro study. J. Pharm. Negat. Results 2022, 13, 4049–4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Product Used | Type of Product | Content | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starbond Ti5 D isc | Grade 5 ‘Eli’ TiAl6V4 titanium alloy | Ti 89.4%, Al 6.2%, V 4%, N + C + H + Fe + O < 0.4% | Scheftner Dental Alloys, Mainz, Germany |

| Straumann ZI | Yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia (3 mol yttria content) | ZrO2 + HfO2 + Y2O3 ≥ 99.0%, Y2O3 4.5–5.6%, ≤5% HfO2, Al2O3 ≤ 0.5%, other oxides ≤ 1% | Amann Girrbach, Koblach, Austria |

| breCAM.BioHPP® | Modified PEEK with ceramic additives | 80%, PEEK 20% nanoceramic filler with particle size varying between 0.3 and 0.5 µm | Bredent GmbH, Senden, Germany |

| Gradia Gum Paste | Gingiva-colored composite | UDMA, dimethacrylate, inorganic fillers (71% by weight), prepolymerized fillers (6% by weight), photoinitiator, stabilizer, pigment | GC America, Inc. Alsip, IL, USA |

| G-Multi Primer | Metal and ceramic primer | Ethanol, MDP, γ-MPTS, MDTP, methacrylate monomer | GC, Tokyo, Japan |

| Gradia Gum Opaque | Gingiva-colored opaque material | Urethane dimethacrylate, silica, alumino-borosilicate glass, campharoquinone, pigment | GC, Tokyo, Japan |

| Anaxgum Gingiva Paste | Gingiva-colored composite | Urethane dimethacrylate, tetramethylene dimethacrylate, BisGMA, silicon dioxide, pigments, initiators, fillers (67% by weight 0.005–3.0 μm) | Anaxdent GmbH Stuttgart, Germany |

| Anaxdent Metal Bonder | Metal primer | Methyl methacrylate, phosphonic acid and macromers with sulfur groups | Anaxdent GmbH Stuttgart, Germany |

| Anaxdent Zircon Bonder | Ceramic primer | Methyl methacrylate, phosphonic acid, and macromers with sulfur groups | Anaxdent GmbH Stuttgart, Germany |

| Anaxgum Opaquer | Gingiva-colored opaque material | Di-urethane dimethacrylate, 2-butylaminocarbonyl oxyethyl acrylate, tetramethylene dimethacrylate, pigment initiators, silica powder | Anaxdent GmbH Stuttgart, Germany |

| SR Nexco Paste | Gingiva-colored composite | Dimethacrylate (17–19%), copolymer, stabilizers, catalysts, pigments (<1%), inorganic filler (43% by weight, 0.01–0.1 µm) | Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein |

| SR Link | Metal and ceramic primer | Phosphoric acid group combined with methacrylate group, ethanol, benzol peroxide | Ivoclar Vivadent Inc. Amherst, NY, USA |

| SR NEXCO Gingiva Opaquer | Gingiva-colored opaque material | Dimethacrylate (65–70%), inorganic filler (<43%), catalyst, stabilizer and pigments (<2%) | Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein |

| Visio.link | PEEK primer | MMA, dimethacrylate, pentaerythritol acrylate, photoinitiators | Bredent GmbH, Senden, Germany |

| Zirconia | Titanium | Modified PEEK | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary application | G-Multi Primer | A layer of primer was applied and allowed to interact for 15–20 s and dried with air. | x | |

| Metal Bonder | x | A layer of primer was applied and allowed to interact for 1 min and dried with air. | x | |

| Zircon Bonder | A layer of primer was applied and allowed to interact for 1 min and dried with air. | x | x | |

| SR Link | A layer of primer was applied and allowed to interact for 20 s and dried with air. | x | ||

| Visio.link | x | x | Applied as a very thin layer, placed in a laboratory-type light device without drying, and polymerized for 3 min. | |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | Partial Eta Squared (η2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Aging | 186.382 | 1 | 186.382 | 289.286 | <0.001 | 0.534 |

| Gingiva-colored Composite | 50.046 | 2 | 25.023 | 38.839 | <0.001 | 0.236 |

| Framework Material | 20.786 | 2 | 10.393 | 16.131 | <0.001 | 0.113 |

| Gingiva-colored Composite * Thermal Aging | 4.570 | 2 | 2.285 | 3.547 | 0.030 | 0.027 |

| Framework Material * Thermal Aging | 21.541 | 2 | 10.771 | 16.717 | <0.001 | 0.117 |

| Gingiva-colored Composite * Framework Material | 30.879 | 4 | 7.720 | 11.982 | <0.001 | 0.160 |

| Gingiva-colored Composite * Framework Material * Thermal Aging | 19.700 | 4 | 4.925 | 7.644 | <0.001 | 0.108 |

| Error | 162.359 | 252 | 0.644 | |||

| Total | 2963.646 | 270 |

| Non-Aged Groups | Thermally Aged Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Titanium | Zirconia | Modified PEEK | Titanium | Zirconia | Modified PEEK | |

| Gingiva-Colored Composite | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD |

| Gradia Gum | 16.35 ± 3.47 | 16.86 ± 3.56 | 8.17 ± 3.53 | 8.89 ± 3.01 | 8.42 ± 3.65 | 5.15 ± 1.90 |

| Aa | Aa | Ba | Aa * | Aa * | Ba * | |

| Anaxgum | 13.65 ± 4.36 | 12.41 ± 4.15 | 7.28 ± 1.94 | 2.89 ± 1.57 | 5.42 ± 3.24 | 4.60 ± 1.04 |

| Aa | Ab | Ba | Bb * | Ab * | Aa * | |

| Nexco | 8.81 ± 3.83 | 10.52 ± 3.14 | 8.29 ± 2.32 | 5.47 ± 1.40 | 2.70 ± 1.72 | 5.39 ± 1.46 |

| Ab | Ab | Aa | Ac * | Bc * | Aa * | |

| Non-Aged Groups | Thermally Aged Groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesive Failure | Cohesive Failure | Mixed Failure | Adhesive Failure | Cohesive Failure | Mixed Failure | ||

| Gradia Gum | Titanium | - | 1 | 14 | - | 1 | 14 |

| Zirconia | - | 1 | 14 | 2 | 1 | 12 | |

| Modified PEEK | 10 | - | 5 | 7 | - | 8 | |

| Anaxgum | Titanium | - | - | 15 | 7 | - | 8 |

| Zirconia | - | 3 | 12 | 4 | 1 | 10 | |

| Modified PEEK | 6 | - | 9 | 12 | - | 3 | |

| Nexco | Titanium | - | 5 | 10 | - | 2 | 13 |

| Zirconia | - | 2 | 13 | 5 | - | 10 | |

| Modified PEEK | 10 | - | 5 | 8 | 1 | 6 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Incearik, S.C.; Aktas, G.; Deniz, D.; Guncu, M.B.; Özcan, M. Effect of Framework Material and Thermal Aging on Shear Bond Strength of Three Different Gingiva-Colored Composite Resins. Materials 2025, 18, 5397. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235397

Incearik SC, Aktas G, Deniz D, Guncu MB, Özcan M. Effect of Framework Material and Thermal Aging on Shear Bond Strength of Three Different Gingiva-Colored Composite Resins. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5397. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235397

Chicago/Turabian StyleIncearik, Saliha Cagla, Guliz Aktas, Diler Deniz, Mustafa Baris Guncu, and Mutlu Özcan. 2025. "Effect of Framework Material and Thermal Aging on Shear Bond Strength of Three Different Gingiva-Colored Composite Resins" Materials 18, no. 23: 5397. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235397

APA StyleIncearik, S. C., Aktas, G., Deniz, D., Guncu, M. B., & Özcan, M. (2025). Effect of Framework Material and Thermal Aging on Shear Bond Strength of Three Different Gingiva-Colored Composite Resins. Materials, 18(23), 5397. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235397