Computational Analysis of Thermal Performance of Heat Sinks with Foam Structures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mathematical Equations of TPMS Lattices

2.2. Geometric Modeling and Boundary Conditions

2.3. Governing Equations

2.4. Methods of Evaluating Mesh Independence

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fluid Flow Characteristics

3.2. Effects of Porosity on Temperature Distribution Across the Length of the Channel

3.3. Log-Mean Temperature Difference (LMTD) in the Heat Sink

3.4. Pressure Gradient in Different HS Geometries

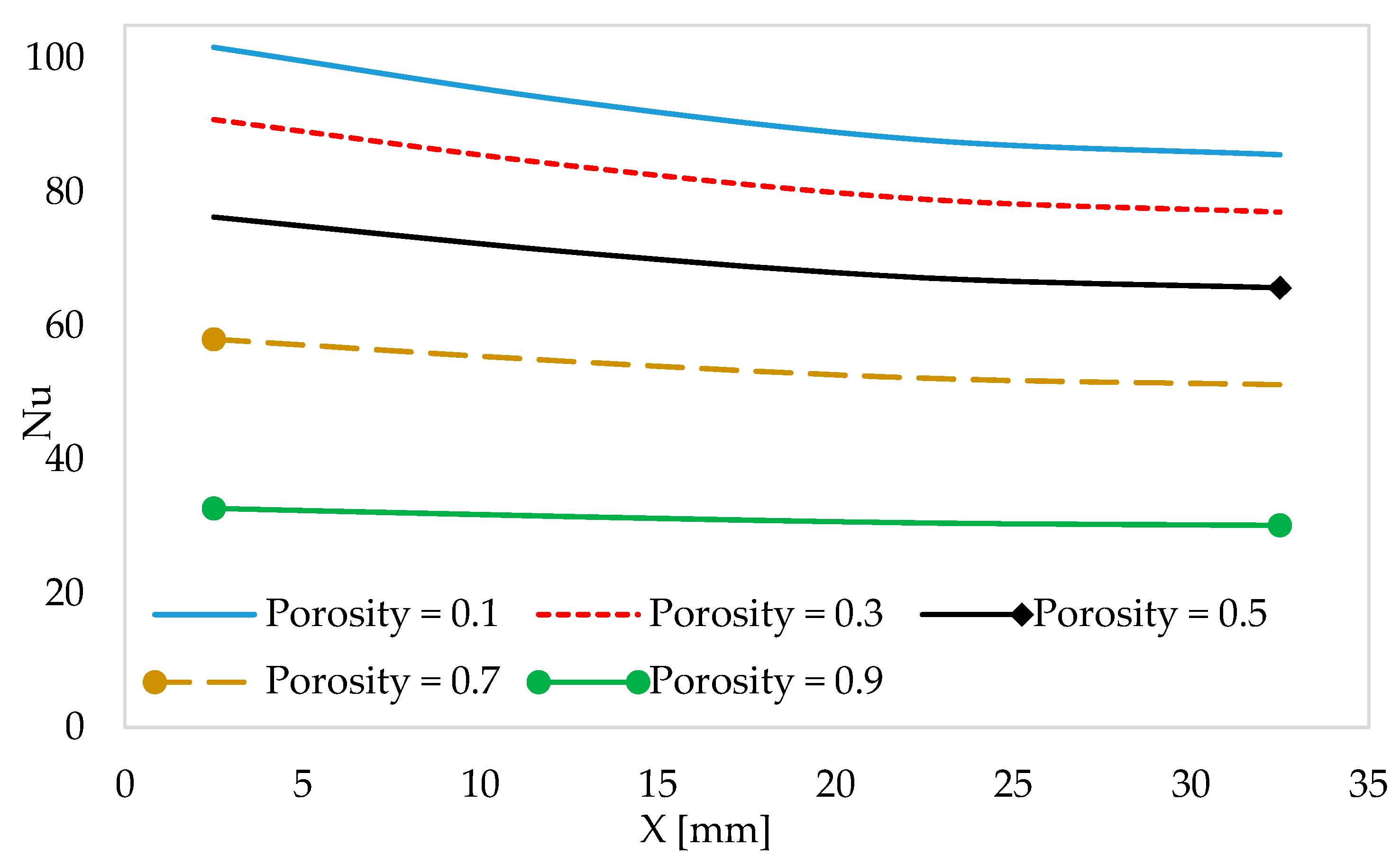

3.5. Local Nusselt Number Distribution Along the Length of the Channel

3.6. Comparison of the Thermal Performances of the Wavy-Fin and TPMS (Gyroid and Primitive) Heat Sinks

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Compared to the traditional wavy-fin structure, the porous TPMS lattice exhibits a higher Nusselt number under the same inlet conditions, including with respect to porosity, permeability, inlet velocity, and inlet temperature. Additionally, the average Nusselt number decreased with the increase in the length of the channel in all heat sink models due to the increasing local temperature.

- (2)

- Among the three structures, the porous gyroid TPMS exhibited the highest pressure gradient. This behavior is primarily attributed to its intricate and highly convoluted geometry, which increases frictional losses within a porous medium.

- (3)

- The temperature profile of the heat sink structure deteriorated with an increase in porosity because a high porosity value allows for larger flow passages that allow greater flow of coolant through the porous structure, enhancing the extraction of heat from the heated surface. However, an increase in porosity leads to lower effective thermal conductivity, which is an important parameter for determining overall thermal performance.

- (4)

- The porous gyroid TPMS structure achieved the highest performance evaluation criterion (PEC) value of 73.39 at a flow velocity of 5 cm/s. Moreover, the gyroid porous structure with a porosity of 0.5 to 0.7 exhibited balanced hydraulic performance and better cooling performance in heat sink analysis. This research summarizes the potential applications of porous TPMS lattice structures in thermal management.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, W.; Zhou, H.; Zeng, Y.; Yan, M.; Jiang, C.; Yang, P.; Li, Q.; Li, Z.; Fu, J.; Huang, Y.; et al. Analysis on the convective heat transfer process and performance evaluation of Triply Periodic Minimal Surface (TPMS) based on Diamond, Gyroid and Iwp. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 201, 123642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, A.; Sathe, A.; Sanap, S. A design approach for thermal enhancement in heat sinks using different types of fins: A review. Front. Therm. Eng. 2023, 2, 980985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnia, M.; Copeland, D.; Soodphakdee, D. A comparison of heat sink geometries for laminar forced convection: Numerical simulation of periodically developed flow. In Proceedings of the Sixth Intersociety Conference on Thermal and Thermomechanical Phenomena in Electronic Systems, Seattle, WA, USA, 27–30 May 1998; pp. 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Tao, J.; Cui, Z.; Zhang, T.; Chen, G. Numerical simulation of fluid and heat transfer characteristics of microchannel heat sink with fan-shaped grooves and triangular truncated ribs. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 155, 107580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohora, F.T.; Haque, M.R.; Haque, M.M. Numerical investigation of the hydrothermal performance of novel pin-fin heat sinks with hyperbolic, wavy, and crinkle geometries and various perforations. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2023, 194, 108578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soodphakdee, D.; Behnia, M.; Copeland, D.W. A comparison of fin geometries for heatsinks in laminar forced convection: Part I-round, elliptical, and plate fins in staggered and in-line configurations. Int. J. Microcircuits Electron. Packag. 2001, 24, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Jajja, S.A.; Ali, W.; Ali, H.M.; Ali, A.M. Water cooled minichannel heat sinks for microprocessor cooling: Effect of fin spacing. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2014, 64, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, S.J. Numerical study of the fluid flow and heat transfer in a finned heat sink using Ansys Icepak. Open Eng. 2023, 13, 20220440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrozek, A.; Strek, T. Numerical Analysis of Dynamic Properties of an Auxetic Structure with Rotating Squares with Holes. Materials 2022, 15, 8712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrozek-Czajkowska, A.; Stręk, T. Design Optimization of the Mechanics of a Metamaterial-Based Prosthetic Foot. Materials 2024, 18, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Ren, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, X.G.; Luo, C.; Xie, Y.M. Lightweight auxetic metamaterials: Design and characteristic study. Compos. Struct. 2022, 293, 115706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, N.; Vesenjak, M.; Kennedy, G.; Thadhani, N.; Ren, Z. Response of Chiral Auxetic Composite Sandwich Panel to Fragment Simulating Projectile Impact. Phys. Status Solidi 2019, 257, 1900099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlaga, B.; Kroma, A.; Poszwa, P.; Kłosowiak, P.; Popielarski, P.; Stręk, T. Heat Transfer Analysis of 3D Printed Wax Injection Mold Used in Investment Casting. Materials 2022, 15, 6545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grima-Cornish, J.N.; Attard, D.; Grima, J.N.; Evans, K.E. Auxetic Behavior and Other Negative Thermomechanical Properties from Rotating Rigid Units. Phys. Status Solidi RRL 2022, 16, 2100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attarzadeh, R.; Rovira, M.; Duwig, C. Design analysis of the “Schwartz D” based heat exchanger: A numerical study. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 177, 121415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeranee, K.; Rao, Y. A review of recent investigations on flow and heat transfer enhancement in cooling channels embedded with triply periodic minimal surfaces (TPMS). Energies 2022, 15, 8994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Al-Ketan, O.; Karathanasopoulos, N. Mechanical performance of solid and sheet network-based stochastic interpenetrating phase composite materials. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 251, 110478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anacreonte, A.V.; Iasiello, M.; Mauro, G.M.; Bianco, N.; Chiu, W.K. Pore-scale multi-objective shape optimization of triply periodic minimal surface cellular architectures: Volumetric Nusselt number versus friction factor. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 236, 126318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cheng, D.; Oo, K.; McCrimmon, T.L.; Bai, S. Design and Additive Manufacturing of TPMS Heat Exchangers. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Gao, Z.; Dai, M.; Song, B.; Yang, B.; Zhang, T.; Yuan, S.; Liu, G.; Zhao, M. Fluid Flow and Heat Transfer Performances of Aluminum Alloy Lattices with Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces. Materials 2025, 18, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baobaid, N.; Ali, M.I.; Khan, K.A.; Al-Rub, R.K.A. Fluid flow and heat transfer of porous TPMS architected heat sinks in free convection environment. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 33, 101944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.H.; Kim, J.E.; Jang, C.H.; Kim, J.; Park, C.Y.; Park, K. Multifunctional gradations of TPMS architected heat exchanger for enhancements in flow and heat exchange performances. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, M.; Rybár, R. Numerical Study of Fluid Flow in a Gyroid-Shaped Heat Transfer Element. Energies 2024, 17, 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, A.; Sun, B. Controlling TPMS lattice deformation for enhanced convective heat transfer: A comparative study of Diamond and Gyroid structures. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 154, 107443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, M.; Rybár, R. Optimisation of Heat Exchanger Performance Using Modified Gyroid-Based TPMS Structures. Processes 2024, 12, 2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Guo, J.; Yang, F.; Zeng, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Zou, C.; Sun, L.; Zeng, Y.; et al. Performance analysis and optimization of the Gyroid-type triply periodic minimal surface heat sink incorporated with fin structures. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 255, 123950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ketan, O.; Ali, M.; Khalil, M.; Rowshan, R.; Khan, K.A.; Abu Al-Rub, R.K. Forced convection computational fluid dynamics analysis of architected and three-dimensional printable heat sinks based on triply periodic minimal surfaces. J. Therm. Sci. Eng. Appl. 2021, 13, 021010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ketan, O.; Abu Al-Rub, R.K. MSLattice: A free software for generating uniform and graded lattices based on triply periodic minimal surfaces. Mat. Des. Process Comm. 2021, 3, e205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutkowski, K.; Kruzel, M.; Rokosz, K. Review of the state-of-the-art uses of minimal surfaces in heat transfer. Energies 2022, 15, 7994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Zhao, J.; Lu, G.; Wang, X.D.; Yan, W.M. Heat transfer enhancement in microchannel heat sink by wavy channel with changing wavelength/amplitude. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2017, 118, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, E.; Sadeghipour, S.M.; Asheghi, M. Heat sinks with enhanced heat transfer capability for electronic cooling applications. J. Electron. Packag. 2006, 128, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayomy, A.M.; Saghir, Z. Thermal performance of finned aluminum heat sink filled with ERG aluminum foam: Experimental and numerical approach. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 4411–4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayomy, A.; Saghir, M. Experimental and Numerical Study of the Heat Transfer Characteristics of Aluminium Metal Foam (with/without channels) Subjected to Steady Water Flow. Pertanika J. Sci. Technol. 2017, 25, 221–246. [Google Scholar]

- Calmidi, V.V.; Mahajan, R. The effective thermal conductivity of high-porosity fibrous metal foams. J. Heat Transf. 1999, 121, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomsma, A.; Poulikakos, D. On the effective thermal conductivity of a three-dimensionally structured fluid-saturated metal foam. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2001, 44, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Nawaz, K.; Park, Y.; Bock, J.; Jacobi, A. Correcting and extending the Boomsma-Poulikakos effective thermal conductivity model for three-dimensional, fluid-saturated metal foams. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2010, 37, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.H.; Bai, J.X.; Yan, H.B.; Kuang, J.J.; Lu, T.J.; Kim, T. An analytical unit cell model for the effective thermal conductivity of high porosity open-cell metal foams. Trans. Porous Media 2014, 102, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, A.; Pan, Y.; Sun, B. Comparative Heat Transfer Performance of TPMS Structures: Spotlight on Fisch Koch S versus Gyroid, Diamond and SplitP Lattices. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Energy Materials and Environment Engineering (ICEMEE 2024), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 14–16 June 2024; p. 01009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, A.; Saeed, M.; Ikhlaq, M.; Imran, M.; Yan, Y. Heat and fluid flow analysis of micro-porous heat sink for electronics cooling: Effect of porosities and pore densities. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 57, 103129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghir, M.Z.; Rahman, M.M. Effectiveness in Cooling a Heat Sink in the Presence of a TPMS Porous Structure Comparing Two Different Flow Directions. Fluids 2024, 9, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Peng, F.; Jia, H.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, P.; Duan, S.; Lei, H. Conformal geometric design and additive manufacturing for special-shaped TPMS heat exchangers. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 247, 127146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, S.; Tran, P.; Marzocca, P. Design and modelling of porous gyroid heatsinks: Influences of cell size, porosity and material variation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 235, 121296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghir, M.Z.; Yahya, M. Convection heat transfer and performance analysis of a triply periodic minimal surface (TPMS) for a novel heat exchanger. Energies 2024, 17, 4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | SA | SA to V Ratio | Lattice Length, [mm] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primitive | 4288 | 2.32 | 15 × 15 × 30 |

| Gyroid | 5183 | 2.82 | |

| Wavy fin | 9496 | 1.86 |

| Boundary | Temperature | Velocity | Pressure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inlet | Tin = 293.15 [K] | - | |

| Outlet | - | - | . |

| Materials | Thermal Conductivity [W/(m K)] | Density [kg/m3] | Specific Heat Capacity [J/(kg K)] | Dynamic Viscosity [kg/(m s)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper | 400 | 8960 | 385 | - |

| Aluminum | 238 | 2700 | 900 | - |

| Water | 0.6 | 997 | 4182 | 0.89 × 10−3 |

| Mesh Size | Domain Elements | Boundary Elements | Edge Elements | Average Nusselt Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extra coarser | 20,866 | 4813 | 693 | 52.3 |

| Coarser | 27,225 | 5901 | 786 | 54.9 |

| Normal | 114,512 | 14,175 | 1228 | 60.9 |

| Fine | 195,069 | 21,295 | 1532 | 61.7 |

| Finer | 504,487 | 39,930 | 2101 | 63.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iticha, W.; Stręk, T. Computational Analysis of Thermal Performance of Heat Sinks with Foam Structures. Materials 2025, 18, 5280. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235280

Iticha W, Stręk T. Computational Analysis of Thermal Performance of Heat Sinks with Foam Structures. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5280. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235280

Chicago/Turabian StyleIticha, Welteji, and Tomasz Stręk. 2025. "Computational Analysis of Thermal Performance of Heat Sinks with Foam Structures" Materials 18, no. 23: 5280. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235280

APA StyleIticha, W., & Stręk, T. (2025). Computational Analysis of Thermal Performance of Heat Sinks with Foam Structures. Materials, 18(23), 5280. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235280