Dynamic Compressive Behavior of Graded Auxetic Lattice Metamaterials: A Combined Theoretical and Numerical Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Experiment

2.1. Simulation Method

2.2. Impact Experiment

2.3. Comparison Between Experiment and Simulation

3. Crashworthiness of Auxetic Lattices

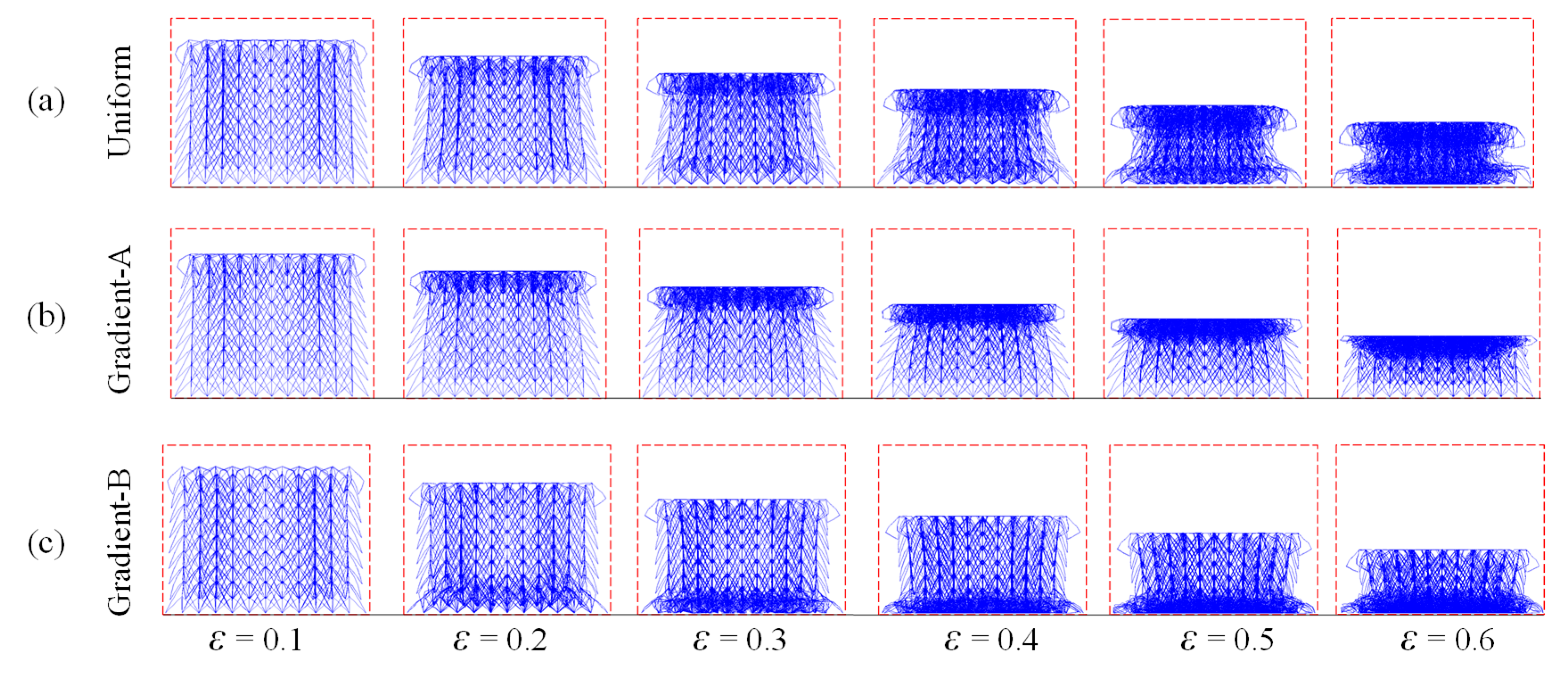

3.1. Graded Auxetic Lattice Configuration

3.2. Criteria for Crashworthiness Evaluation

3.3. Dynamic Compression of Auxetic Lattices

3.3.1. Compressive Velocity of 1 m/s

3.3.2. Compressive Velocity of 10 m/s

3.3.3. Compressive Velocity of 100 m/s

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Analysis Models

4.1.1. Quasi-Static Compression

4.1.2. Dynamic Compression

4.2. Parametric Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NPR | Negative Poisson’s ratio |

| FE | Finite element |

| SLM | Selective laser melting |

| SEA | Specific energy absorption |

Appendix A

References

- Gibson, L.J.; Ashby, M.F. Cellular Solids: Structure and Properties; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schaedler, T.A.; Carter, W.B. Architected cellular materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. 2016, 46, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaedler, T.A.; Jacobsen, A.J.; Torrents, A.; Sorensen, A.E.; Lian, J.; Greer, J.R.; Valdevit, L.; Carter, W.B. Ultralight metallic microlattices. Science 2011, 334, 962–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Lee, H.; Weisgraber, T.H.; Shusteff, M.; DeOtte, J.; Duoss, E.B.; Kuntz, J.D.; Biener, M.M.; Ge, Q.; Jackson, J.A. Ultralight, ultrastiff mechanical metamaterials. Science 2014, 344, 1373–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Hsieh, M.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Lin, Y.; Shen, Q.; Chen, F.; Zhang, L. Architectural design and additive manufacturing of mechanical metamaterials: A review. Engineering 2022, 17, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, V.S.; Fleck, N.A.; Ashby, M.F. Effective properties of the octet-truss lattice material. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2001, 49, 1747–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonella, S.; Ruzzene, M. Homogenization and equivalent in-plane properties of two-dimensional periodic lattices. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2008, 45, 2897–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, R.G.; Fleck, N.A. The structural performance of the periodic truss. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2006, 54, 756–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, M.F. The properties of foams and lattices. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2005, 364, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaedler, T.A.; Ro, C.J.; Sorensen, A.E.; Eckel, Z.; Yang, S.S.; Carter, W.B.; Jacobsen, A.J. Designing metallic microlattices for energy absorber applications. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2014, 16, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.G.; He, M.; Deshpande, V.S.; Hutchinson, J.W.; Jacobsen, A.J.; Carter, W.B. Concepts for enhanced energy absorption using hollow micro-lattices. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2010, 37, 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdevit, L.; Godfrey, S.W.; Schaedler, T.A.; Jacobsen, A.J.; Carter, W.B. Compressive strength of hollow microlattices: Experimental characterization, modeling, and optimal design. J. Mater. Res. 2013, 28, 2461–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakes, R. Foam structures with a negative Poisson’s ratio. Science 1987, 235, 1038–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Luo, Z.; Yin, Q. Negative Poisson’s ratio effect of re-entrant anti-trichiral honeycombs under large deformation. Thin-Walled Struct. 2019, 141, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, B.; Ma, L. Mechanical properties of 3D double-U auxetic structures. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2019, 180, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhan, L.; Miao, X.; Hu, L.; Li, E.; Zou, T. Morning glory-inspired lattice structure with negative Poisson’s ratio effect. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 232, 107643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wei, X.; Han, X.; Zhou, Z.; Xiong, J. Novel 3D auxetic lattice structures developed based on the rotating rigid mechanism. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2021, 233, 111232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Hong, W.; Zhao, Z.; Hamel, C.; Chen, M.; Lu, H.; Qi, H.J. 3D printing of auxetic metamaterials with digitally reprogrammable shape. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 22768–22776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, A.; Mahesh, V.; Harursampath, D. On the application of additive manufacturing methods for auxetic structures: A review. Adv. Manuf. 2021, 9, 342–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, K.; Calius, E.; Singamneni, S. An enhanced square-grid structure for additive manufacturing and improved auxetic responses. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Des. 2019, 15, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayati, R.; Güven, A.; Van Der Zwaag, S. 3D gradient auxetic soft mechanical metamaterials fabricated by additive manufacturing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 118, 141904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Pan, R.; Yan, C.; He, M.; Chen, Q.; Li, S.; Chen, X.; Hao, L.; Li, Y. Subdivisional modelling method for matched metal additive manufacturing and its implementation on novel negative Poisson’s ratio lattice structures. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 68, 103525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbalzano, G.; Tran, P.; Ngo, T.D.; Lee, P.V. A numerical study of auxetic composite panels under blast loadings. Compos. Struct. 2016, 135, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, N.; Vesenjak, M.; Ren, Z. Auxetic Cellular Materials-a Review. Stroj. Vestn.-J. Mech. Eng. 2016, 62, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Chen, Y.; Hu, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, L. Exploiting negative Poisson’s ratio to design 3D-printed composites with enhanced mechanical properties. Mater. Des. 2018, 142, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Yin, J.; Wen, J.; Yu, D. Mechanical properties of 3D-printed hierarchical structures based on Sierpinski triangles. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 247, 108172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, S.; Shao, J.; Wu, X. Novel negative Poisson’s ratio lattice structures with enhanced stiffness and energy absorption capacity. Materials 2018, 11, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Vora, H.D.; Chang, Y. Behavior of auxetic structures under compression and impact forces. Smart Mater. Struct. 2018, 27, 025012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Gao, Q.; Wang, L.; Yu, Q.; Ma, Z. Dynamic crushing of double-arrowed auxetic structure under impact loading. Mater. Des. 2018, 160, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liu, F.; Wang, L. Enhancing indentation and impact resistance in auxetic composite materials. Compos. B Eng. 2020, 198, 108229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.C.; Ren, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, X.G.; Luo, C.; Cheng, X.; Xie, Y.M. Mechanical properties of foam-filled hexagonal and re-entrant honeycombs under uniaxial compression. Compos. Struct. 2021, 280, 114922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.G.; Ren, X.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, X.Y.; Luo, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Y.M. A novel auxetic chiral lattice composite: Experimental and numerical study. Compos. Struct. 2022, 282, 115043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskery, I.; Hussey, A.; Panesar, A.; Aremu, A.; Tuck, C.; Ashcroft, I.; Hague, R. An investigation into reinforced and functionally graded lattice structures. J. Cell. Plast. 2017, 53, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panesar, A.; Abdi, M.; Hickman, D.; Ashcroft, I. Strategies for functionally graded lattice structures derived using topology optimisation for additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 19, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajdari, A.; Nayeb-Hashemi, H.; Vaziri, A. Dynamic crushing and energy absorption of regular, irregular and functionally graded cellular structures. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2011, 48, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iandiorio, C.; Mattei, G.; Marotta, E.; Costanza, G.; Tata, M.E.; Salvini, P. The Beneficial Effect of a TPMS-Based Fillet Shape on the Mechanical Strength of Metal Cubic Lattice Structures. Materials 2024, 17, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, S.Y.; Sun, C.N.; Leong, K.F.; Wei, J. Compressive properties of functionally graded lattice structures manufactured by selective laser melting. Mater. Des. 2017, 131, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niknam, H.; Akbarzadeh, A. Graded lattice structures: Simultaneous enhancement in stiffness and energy absorption. Mater. Des. 2020, 196, 109129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, S.; Peng, C. Dynamic uniaxial crushing of wood. Int. J. Impact Eng. 1997, 19, 531–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Zhang, J.; Yu, T. Collapse of periodic planar lattices under uniaxial compression, part II: Dynamic crushing based on finite element simulation. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2009, 36, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Qin, Q.; Wang, T. Impact plastic crushing and design of density-graded cellular materials. Mech. Mater. 2016, 94, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Yang, J.; Lin, H. Theoretical investigation on impact resistance and energy absorption of foams with nonlinearly varying density. Compos. B Eng. 2017, 116, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Shen, H.S.; Wang, H.; Yu, Z. Large amplitude vibration of sandwich plates with functionally graded auxetic 3D lattice core. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2020, 174, 105472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Shen, H.-S.; Wang, H. Postbuckling behavior of sandwich plates with functionally graded auxetic 3D lattice core. Compos. Struct. 2020, 237, 111894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Yang, X.; Zhang, W.; Xia, Y. Design of energy-dissipating structure with functionally graded auxetic cellular material. Int. J. Crashworthiness 2018, 23, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Chen, C. Impact resistance of uniform and functionally graded auxetic double arrowhead honeycombs. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2015, 83, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, N.; Luo, T.; Lin, Z. In-plane dynamic crushing of re-entrant auxetic cellular structure. Mater. Des. 2016, 100, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Dong, Z.; Li, Y.; Wu, W.; Fang, D. Compression behavior of the graded metallic auxetic reentrant honeycomb: Experiment and finite element analysis. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 758, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Meng, J.; Ma, G.; Ren, S.; Fang, L.; Cao, X.; Liu, L.; Li, H.; Wu, W.; Xiao, D. Insight into the negative Poisson’s ratio effect of the gradient auxetic reentrant honeycombs. Compos. Struct. 2021, 274, 114366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, N.; Krstulović-Opara, L.; Ren, Z.; Vesenjak, M. Compression and shear behaviour of graded chiral auxetic structures. Mech. Mater. 2020, 148, 103524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, C.; Chen, S. Fabrication and crushing response of graded re-entrant circular auxetic honeycomb. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 242, 107999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Xie, Y.M.; Ren, X. Mechanical characterization of a novel thickness gradient auxetic tubular structure under inclined load. Eng. Struct. 2022, 273, 115079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, Z.; Hernandez-Nava, E.; Tyas, A.; Warren, J.A.; Fay, S.D.; Goodall, R.; Todd, I.; Askes, H. Energy absorption in lattice structures in dynamics: Experiments. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2016, 89, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, Z.; Tyas, A.; Goodall, R.; Askes, H. Energy absorption in lattice structures in dynamics: Nonlinear FE simulations. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2017, 102, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallquist, J.O. LS-DYNA3D Theoretical Manual; Livermore Software Technology Corporation: Livermore, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Yu, Y.Y.; Wei, Y.P.; Huang, C.G. Crushing behavior of a thin-walled circular tube with internal gradient grooves fabricated by SLM 3D printing. Thin-Walled Struct. 2017, 111, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.F. Constitutive and failure behaviour in selective laser melted stainless steel for microlattice structures. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 622, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platek, P.; Sienkiewicz, J.; Janiszewski, J.; Jiang, F.C. Investigations on Mechanical Properties of Lattice Structures with Different Values of Relative Density Made from 316L by Selective Laser Melting (SLM). Materials 2020, 13, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, M.S.; Kayacan, M.Y.; Alshihabi, M. Evaluation of energy absorption performance and Johnson-Cook parameters of lattice-structured steel parts manufactured via SLM. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 137, 5293–5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, N.; Vesenjak, M.; Tanaka, S.; Hokamoto, K.; Ren, Z. Compressive behaviour of chiral auxetic cellular structures at different strain rates. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2020, 141, 103566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Magkiriadis, I.; Harrigan, J.J. Compressive strain at the onset of densification of cellular solids. J. Cell. Plast. 2006, 42, 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Uniform | Gradient-A | Gradient-B | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEA(kJ/kg) | 19.22 | 21.49 | 19.27 |

| σm (MPa) | 30.89 | 18.50 | 22.13 |

| σpl (MPa) | 23.52 | 33.97 | 29.20 |

| εd | 0.628 | 0.771 | 0.742 |

| Uniform | Gradient-A | Gradient-B | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEA(kJ/kg) | 20.29 | 21.95 | 21.64 |

| σm (MPa) | 38.65 | 26.23 | 33.90 |

| σpl (MPa) | 25.07 | 34.38 | 31.68 |

| εd | 0.678 | 0.758 | 0.765 |

| Uniform | Gradient-A | Gradient-B | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEA(kJ/kg) | 34.98 | 41.22 | 36.01 |

| σm (MPa) | 119.94 | 74.97 | 169.49 |

| σpl (MPa) | 52.65 | 67.64 | 52.50 |

| εd | 0.802 | 0.851 | 0.822 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Ou, Z. Dynamic Compressive Behavior of Graded Auxetic Lattice Metamaterials: A Combined Theoretical and Numerical Study. Materials 2025, 18, 5187. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225187

Chen Z, Liu J, Li X, Zhou Y, Ou Z. Dynamic Compressive Behavior of Graded Auxetic Lattice Metamaterials: A Combined Theoretical and Numerical Study. Materials. 2025; 18(22):5187. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225187

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Zeyao, Jinjie Liu, Xinhao Li, Yixin Zhou, and Zhihao Ou. 2025. "Dynamic Compressive Behavior of Graded Auxetic Lattice Metamaterials: A Combined Theoretical and Numerical Study" Materials 18, no. 22: 5187. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225187

APA StyleChen, Z., Liu, J., Li, X., Zhou, Y., & Ou, Z. (2025). Dynamic Compressive Behavior of Graded Auxetic Lattice Metamaterials: A Combined Theoretical and Numerical Study. Materials, 18(22), 5187. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225187