A Finite Element Study of Bimodulus Materials with 2D Constitutive Relations in Non-Principal Stress Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

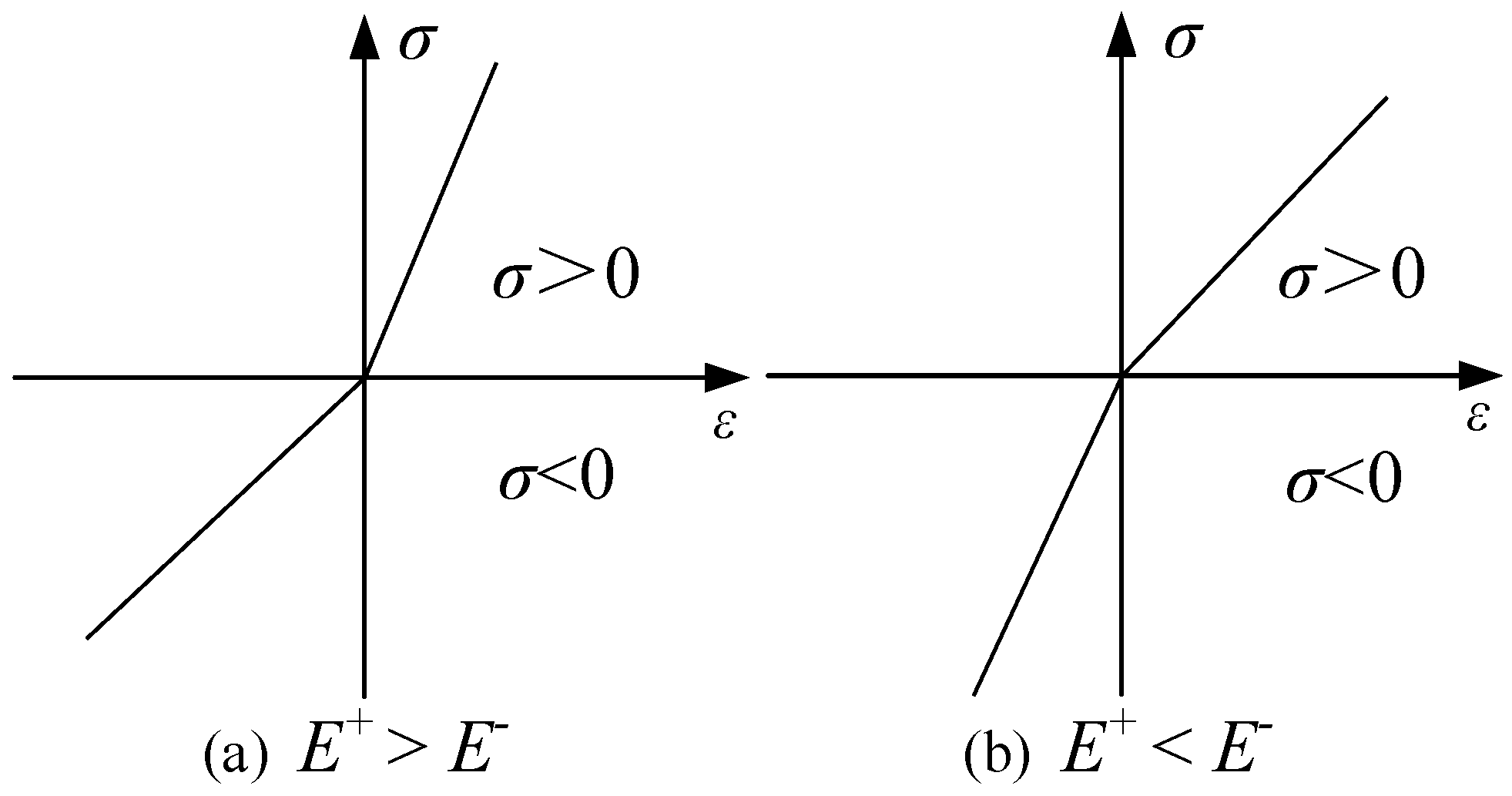

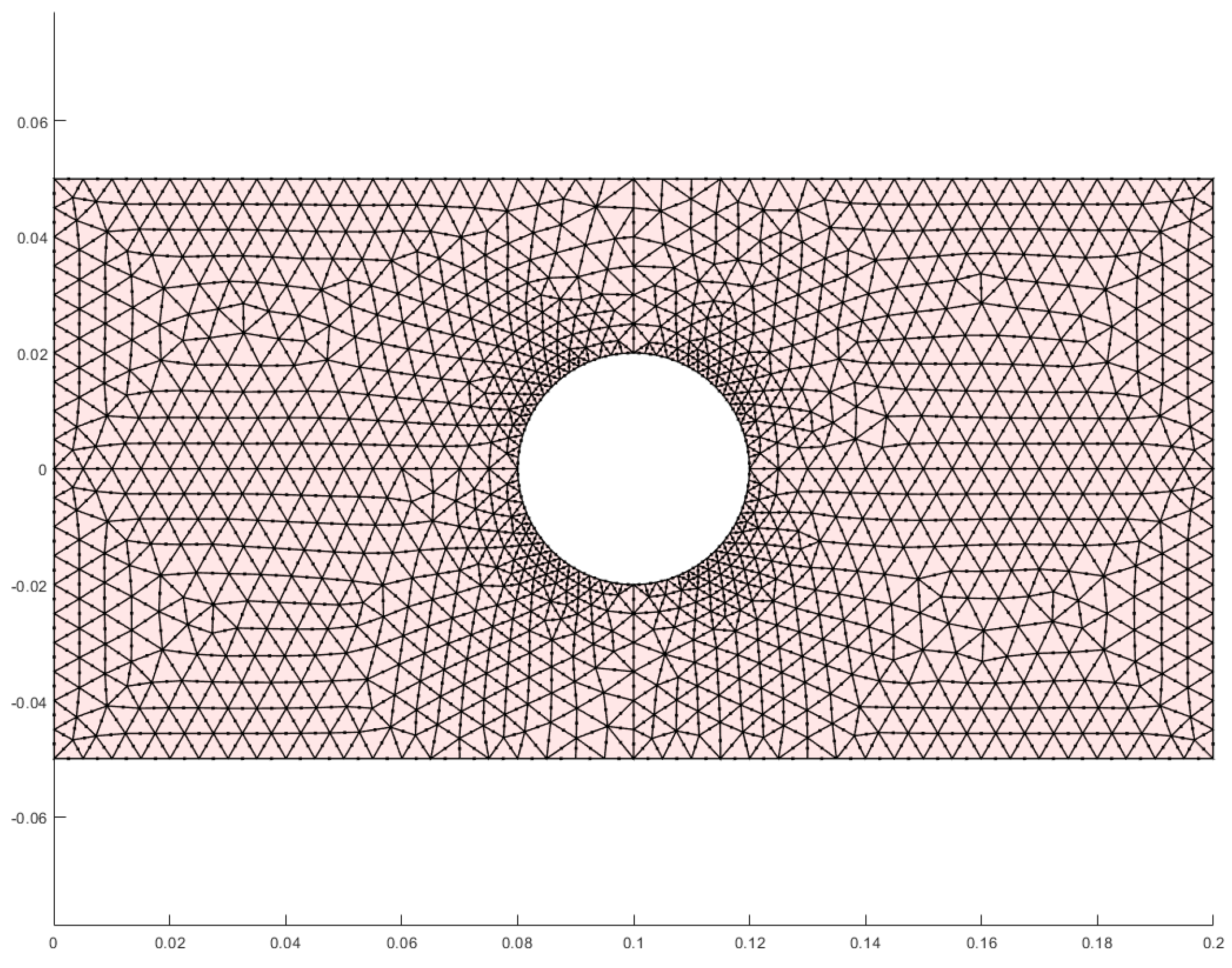

2.1. Principal Stress-Based Bimodulus Model

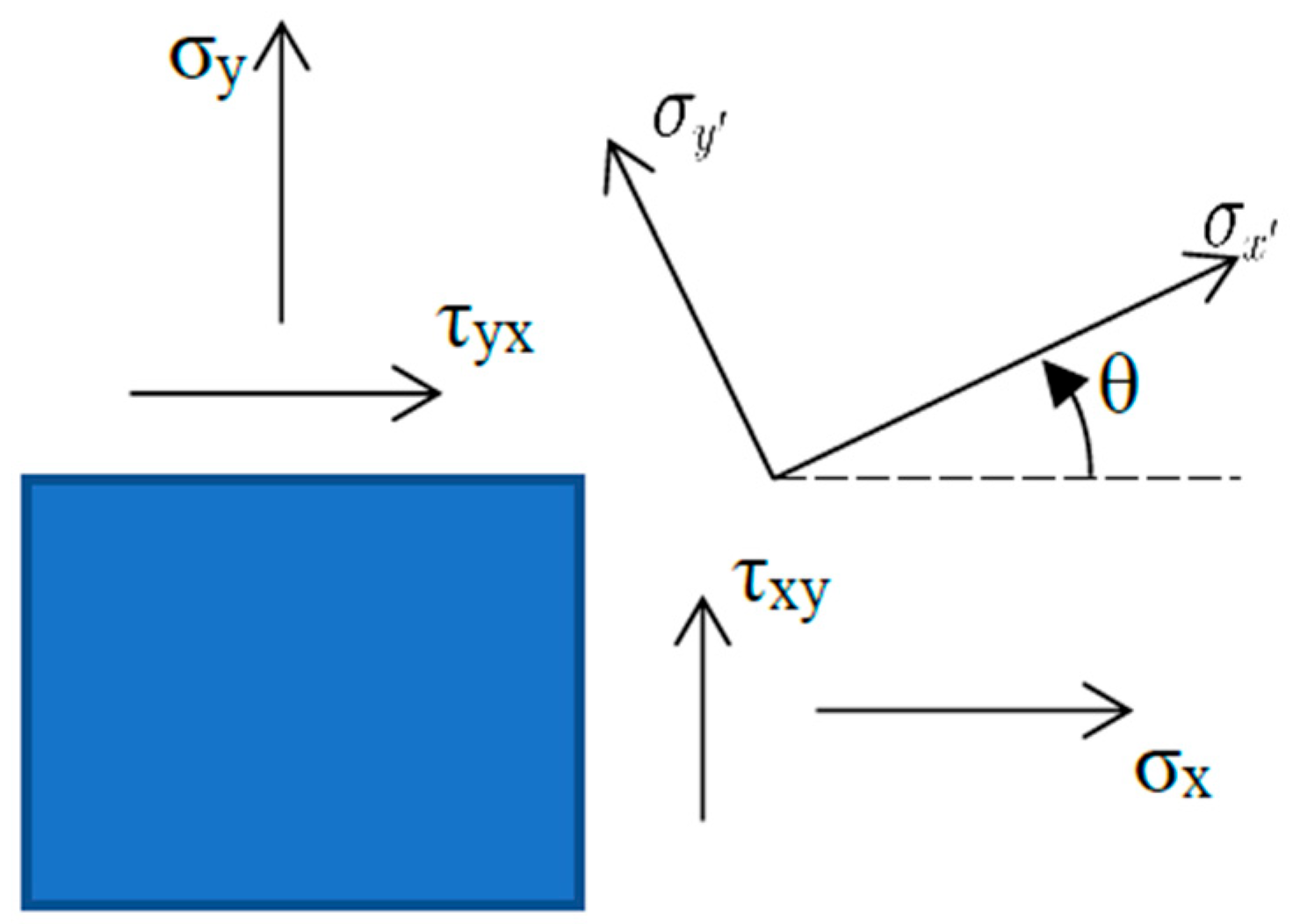

2.2. The Axis Transformation Formula

2.3. General Stress–Strain Relationship in Non-Principal Stress Directions

2.4. Finite Element Interpolation Functions

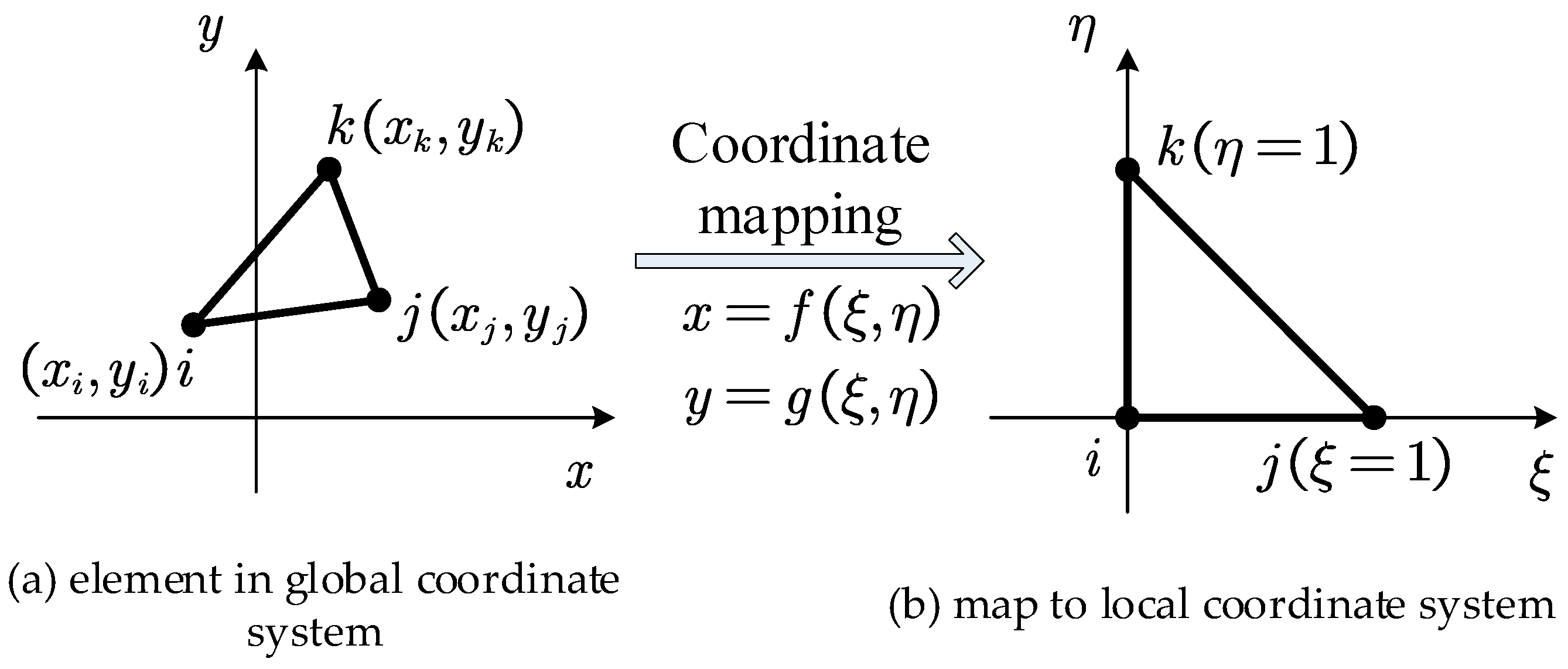

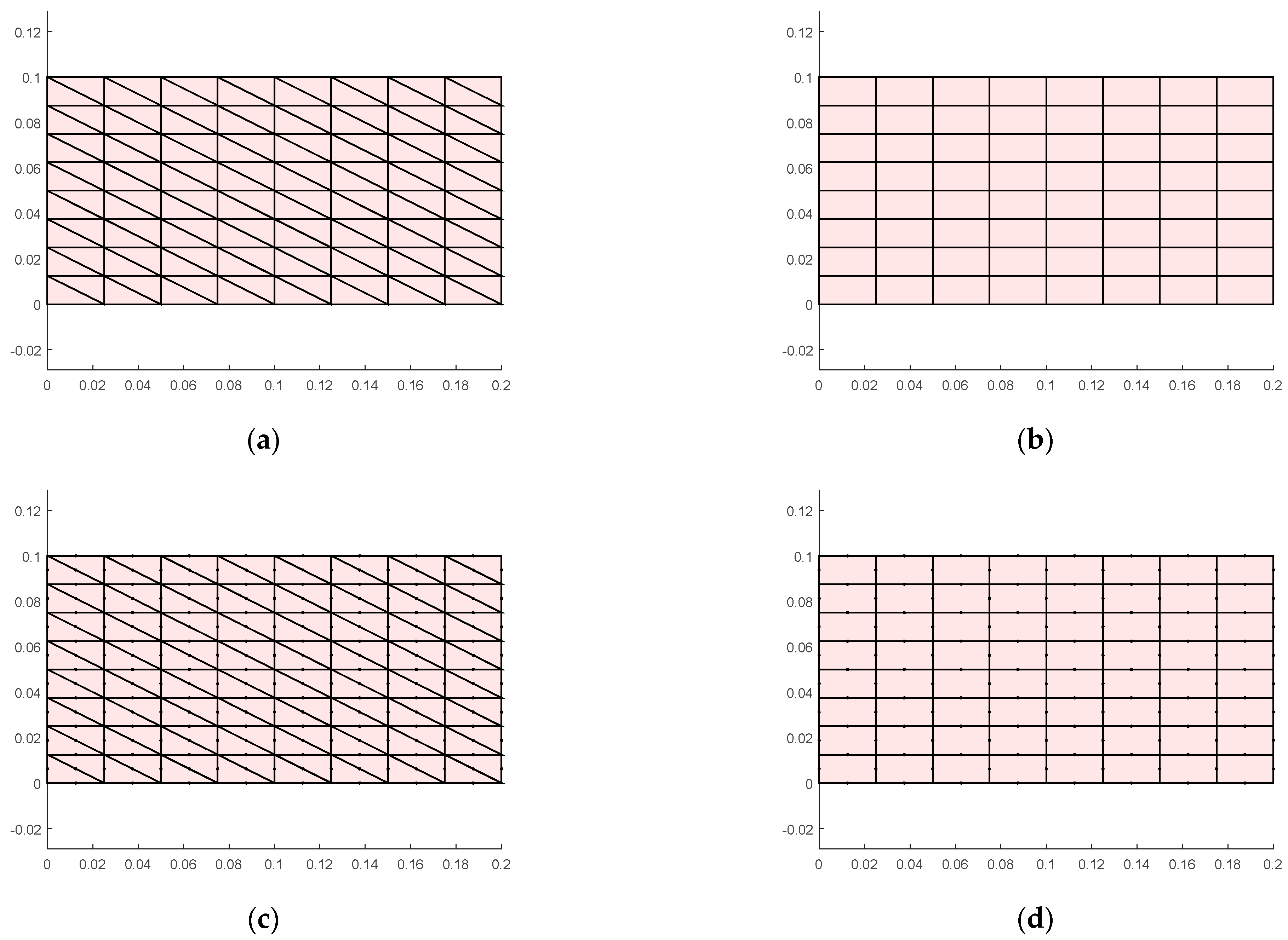

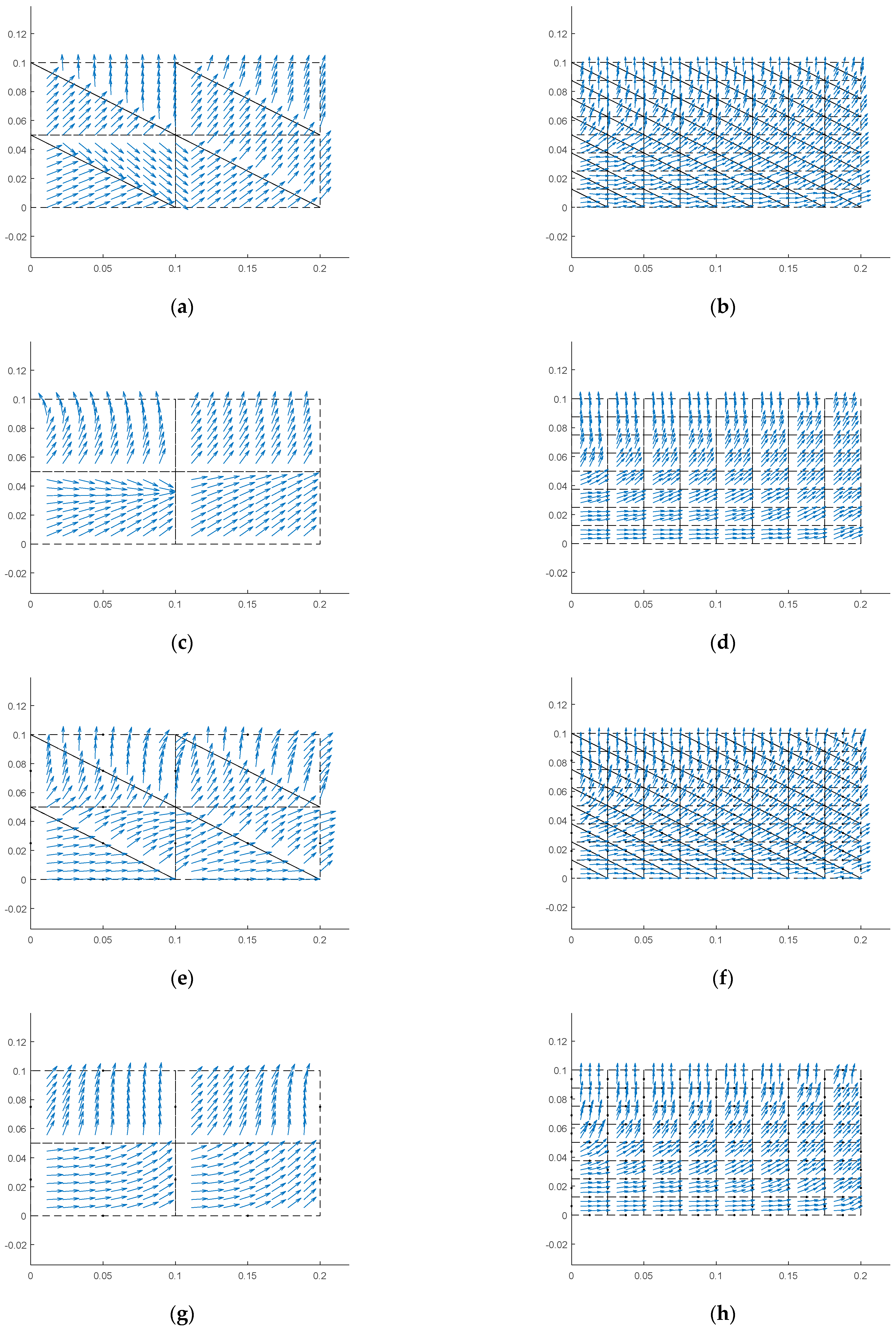

2.4.1. Triangular Element with Three Nodes

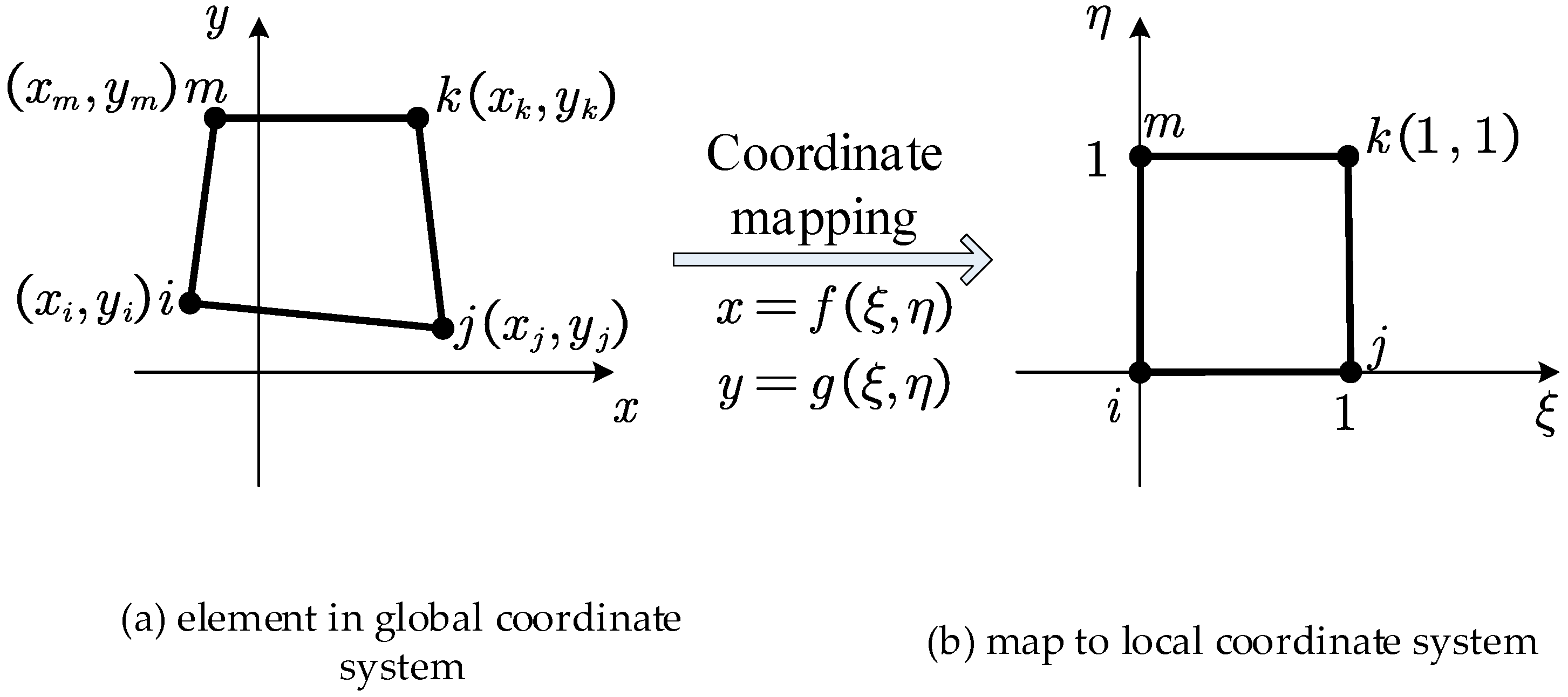

2.4.2. Rectangular Element with Four Nodes

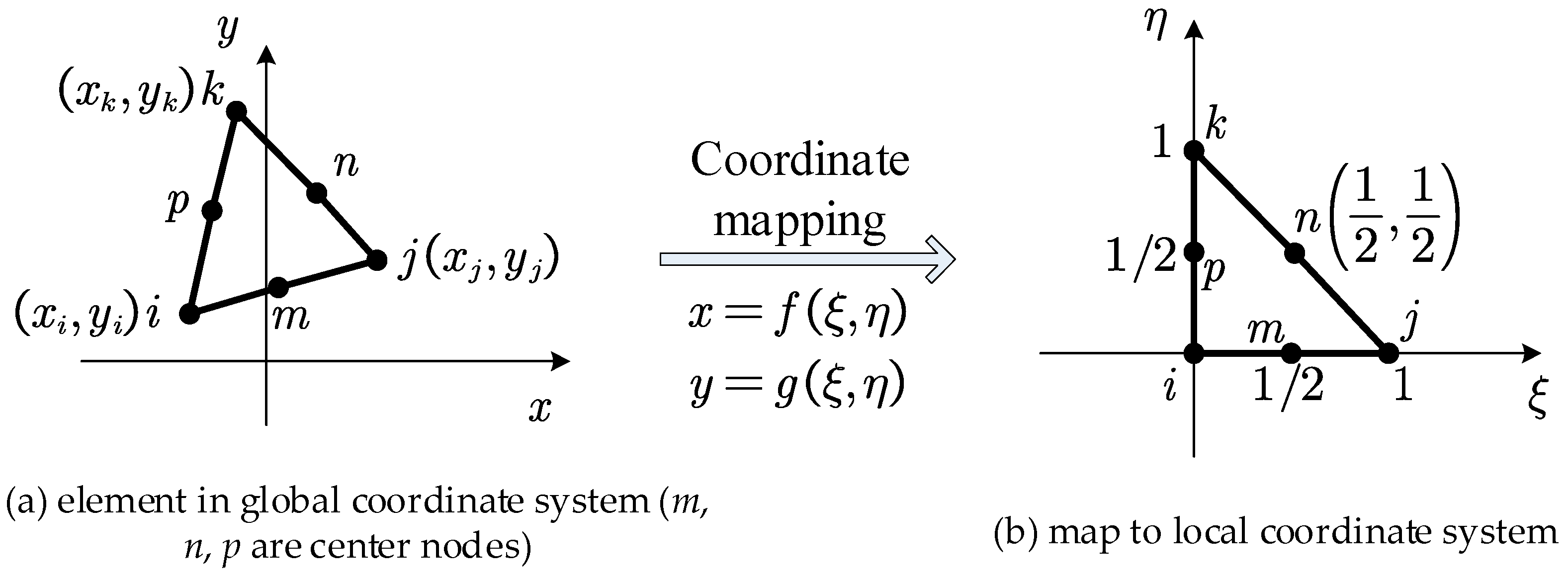

2.4.3. Triangular Element with Six Nodes

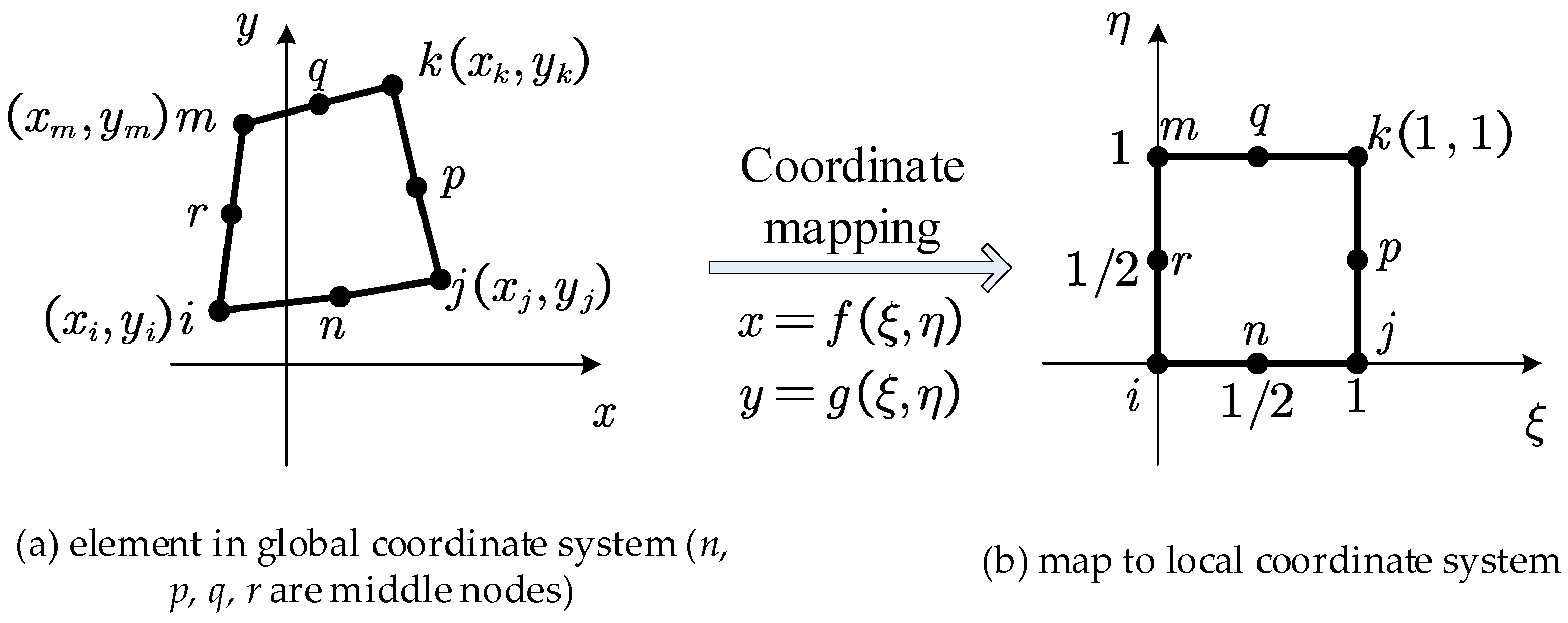

2.4.4. Rectangular Element with Eight Nodes

2.5. Element Equations

2.6. Principal Stress Direction Angles of the Element

2.6.1. Triangular Element with Three Nodes

2.6.2. Quadrilateral Element with Four Nodes

2.6.3. Triangular Element with Six Nodes

2.6.4. Quadrilateral Element with Eight Nodes

2.7. Overall Equations

3. Solution Methods and Model Verification

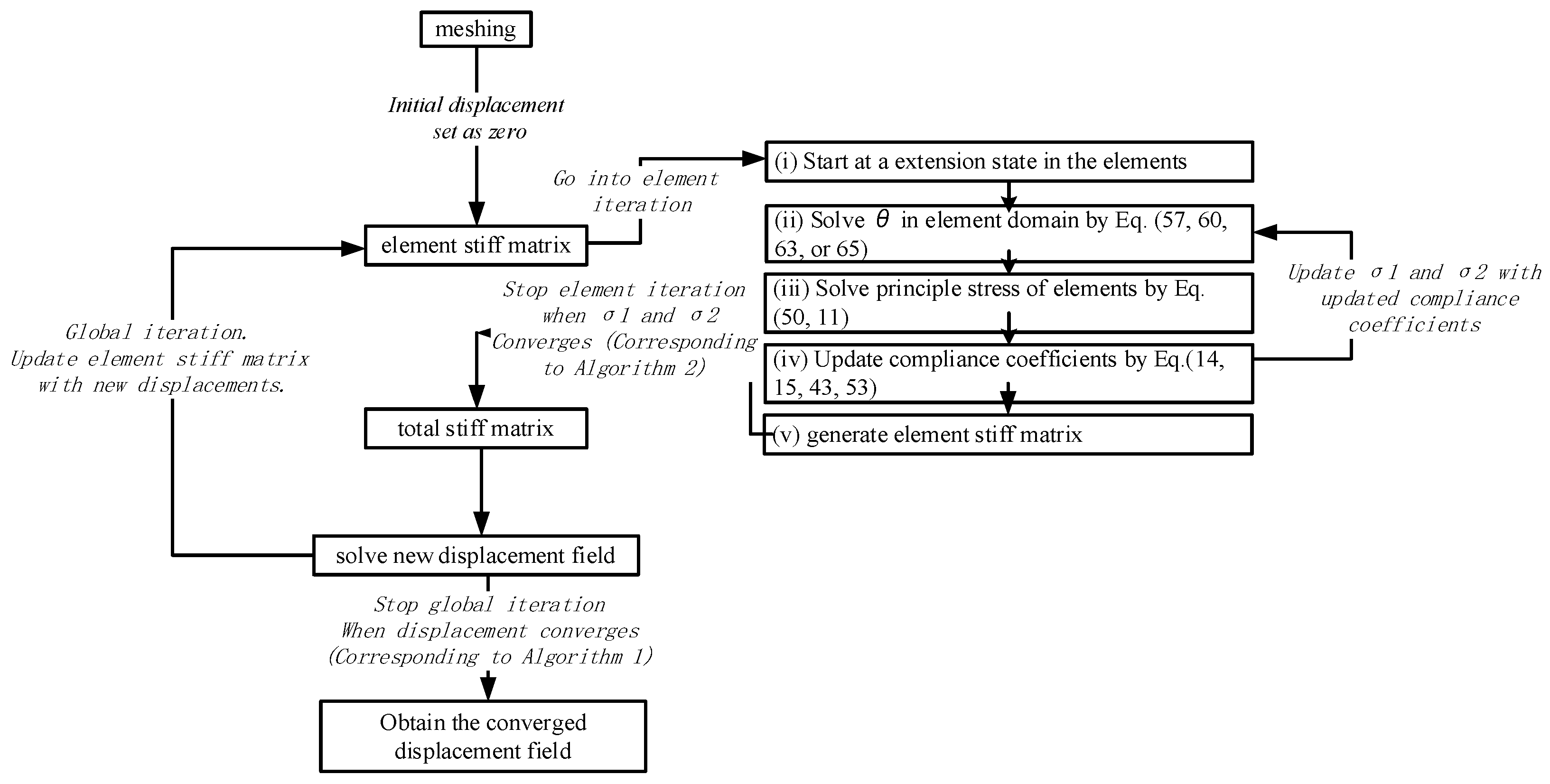

3.1. Solution Methods

| Algorithm 1 Code block to determine if displacement breaks out of the loop | |

| 1 | if norm(totalDisplaceOld − totalDisplace)/norm(totalDisplace) < 1e-6 |

| 2 | break; |

| 3 | end |

| Algorithm 2 Code block to determine if σ1 and σ2 break out of the loop | |

| 1 | if norm(sigma1_new-sigma1) == 0 && norm(sigma2_new-sigma2) == 0 |

| 2 | break; |

| 3 | end |

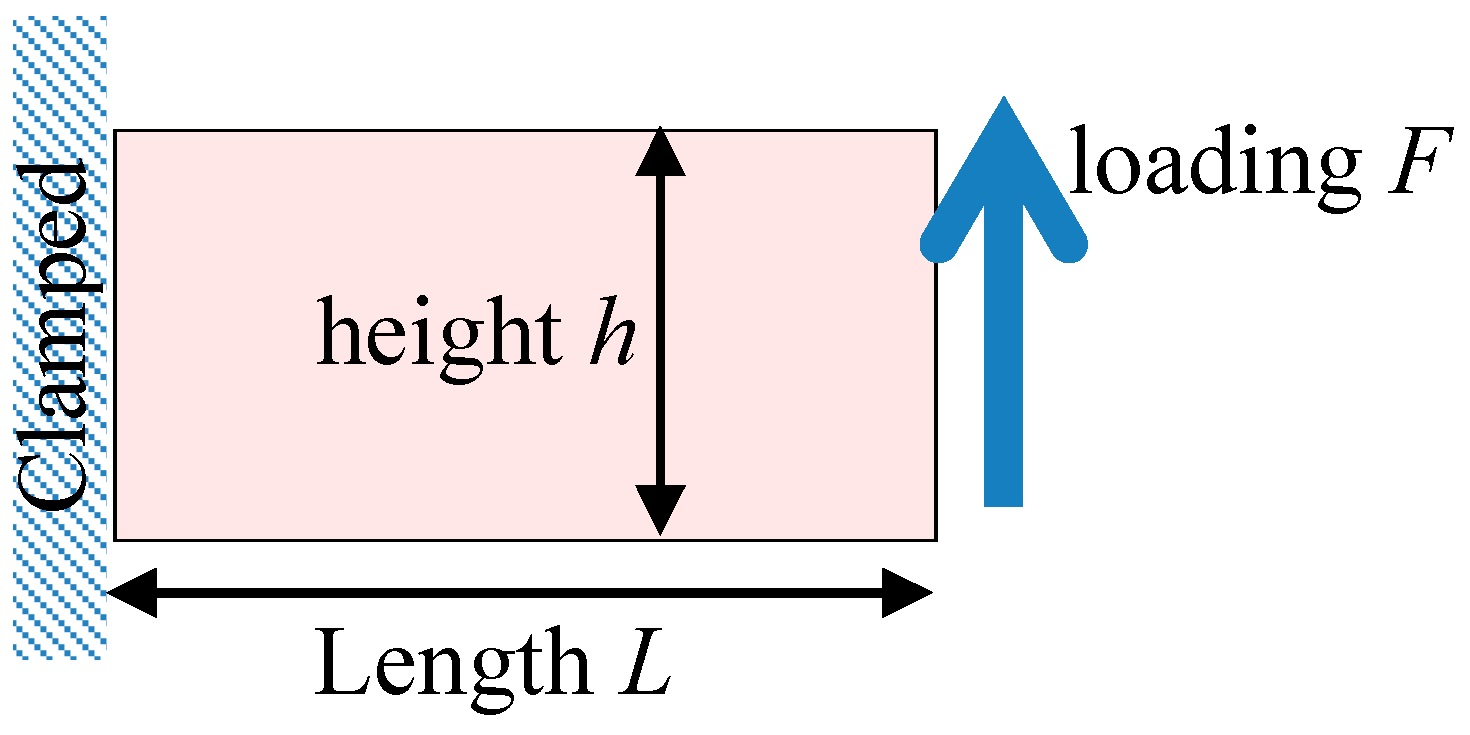

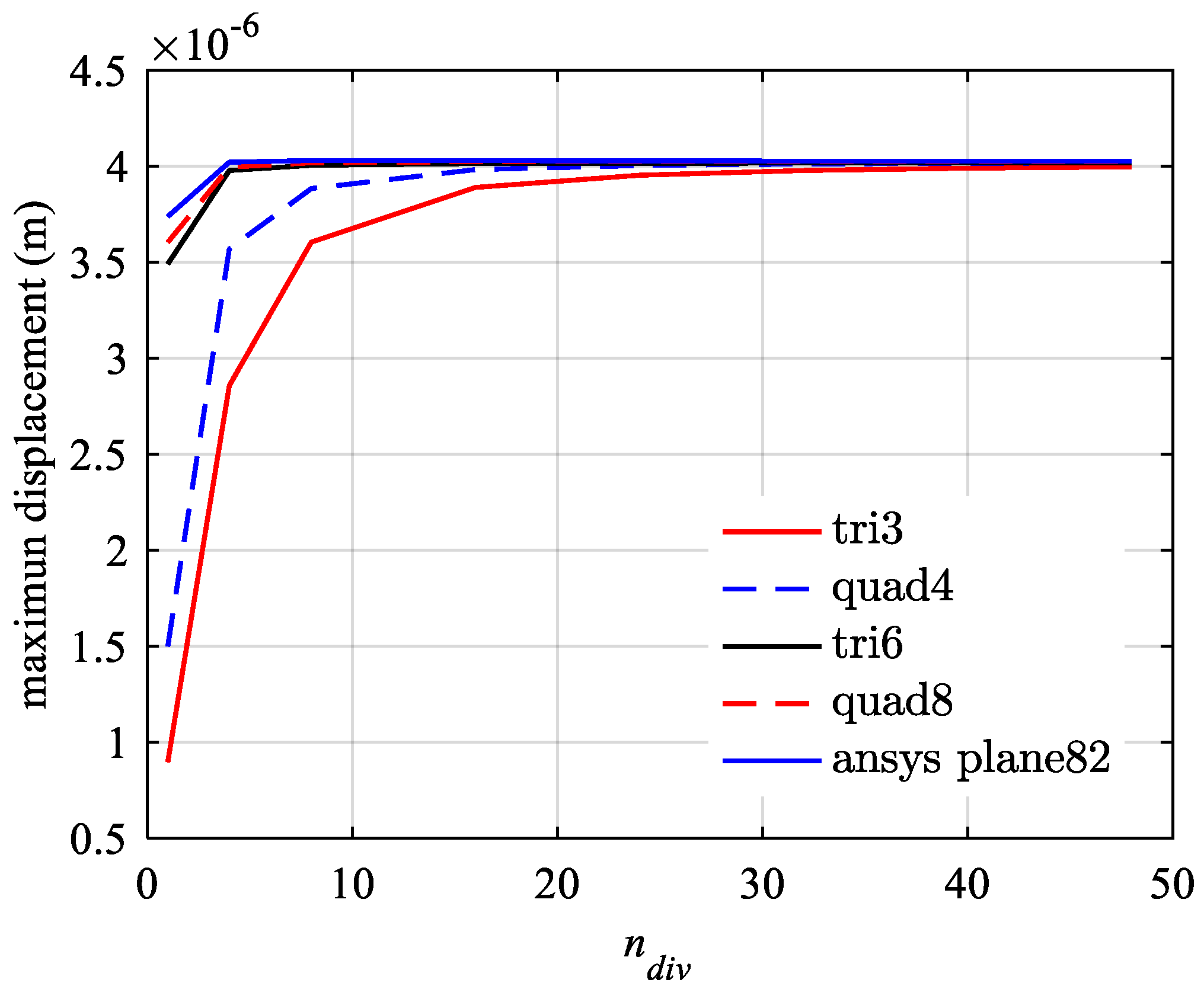

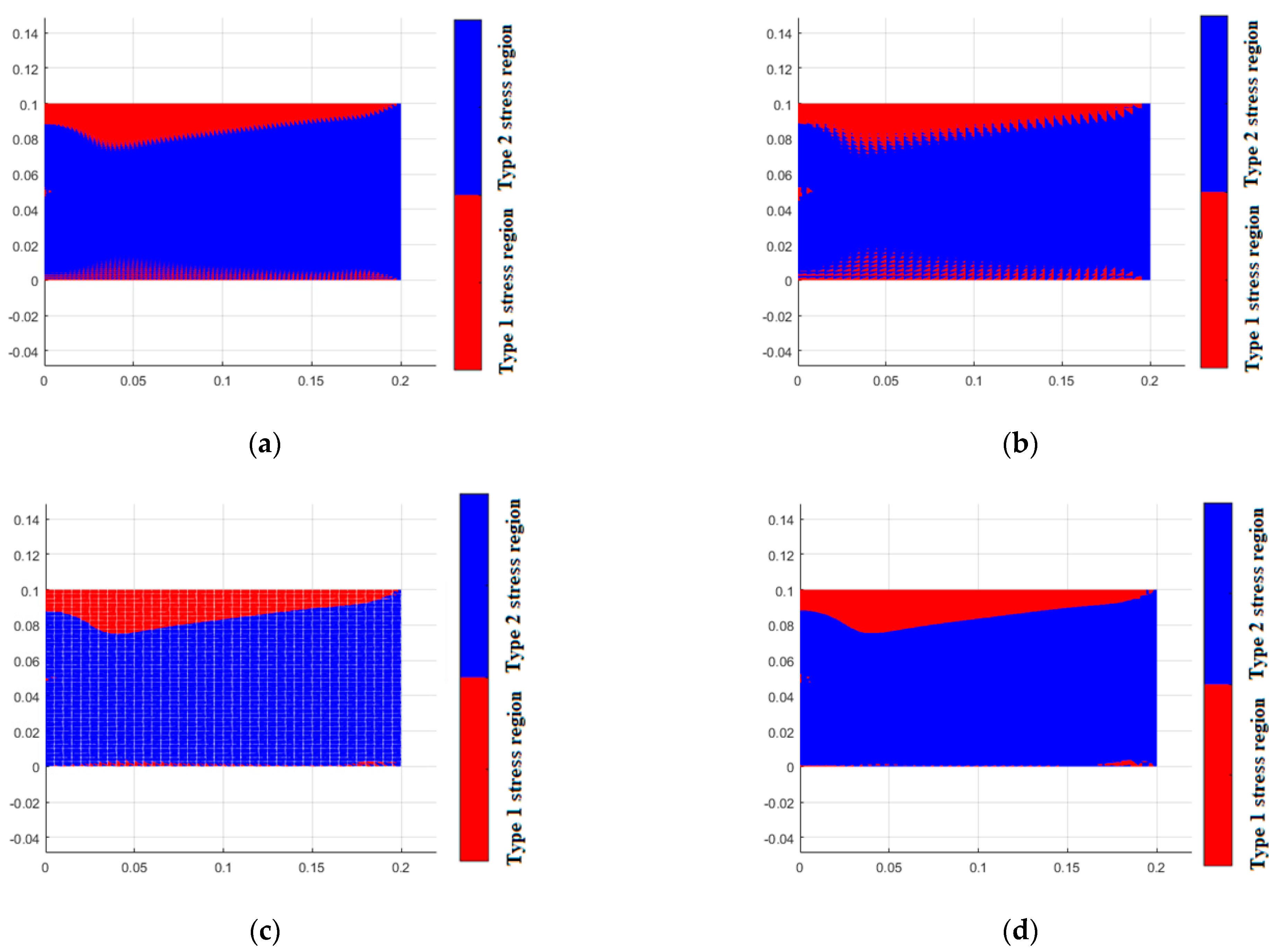

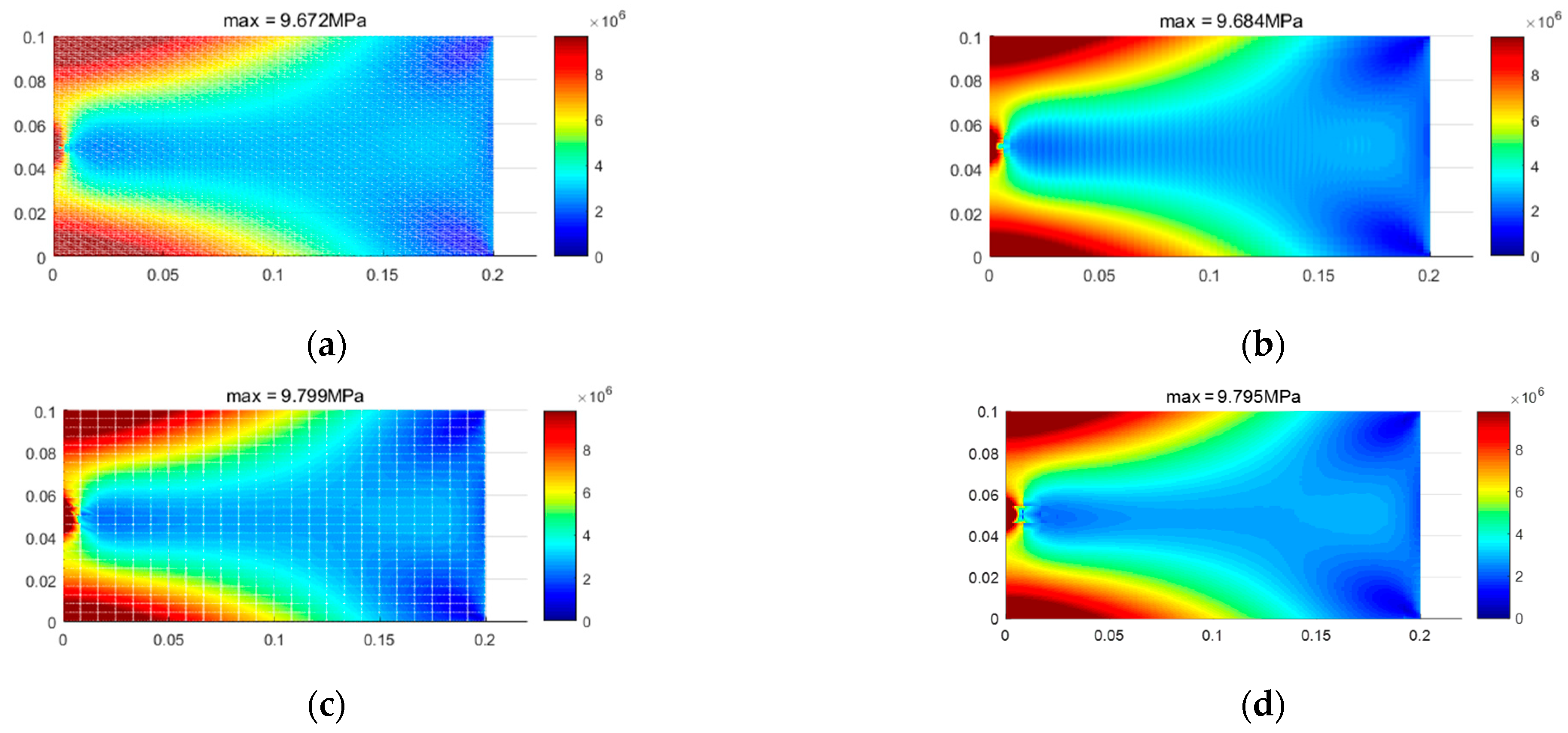

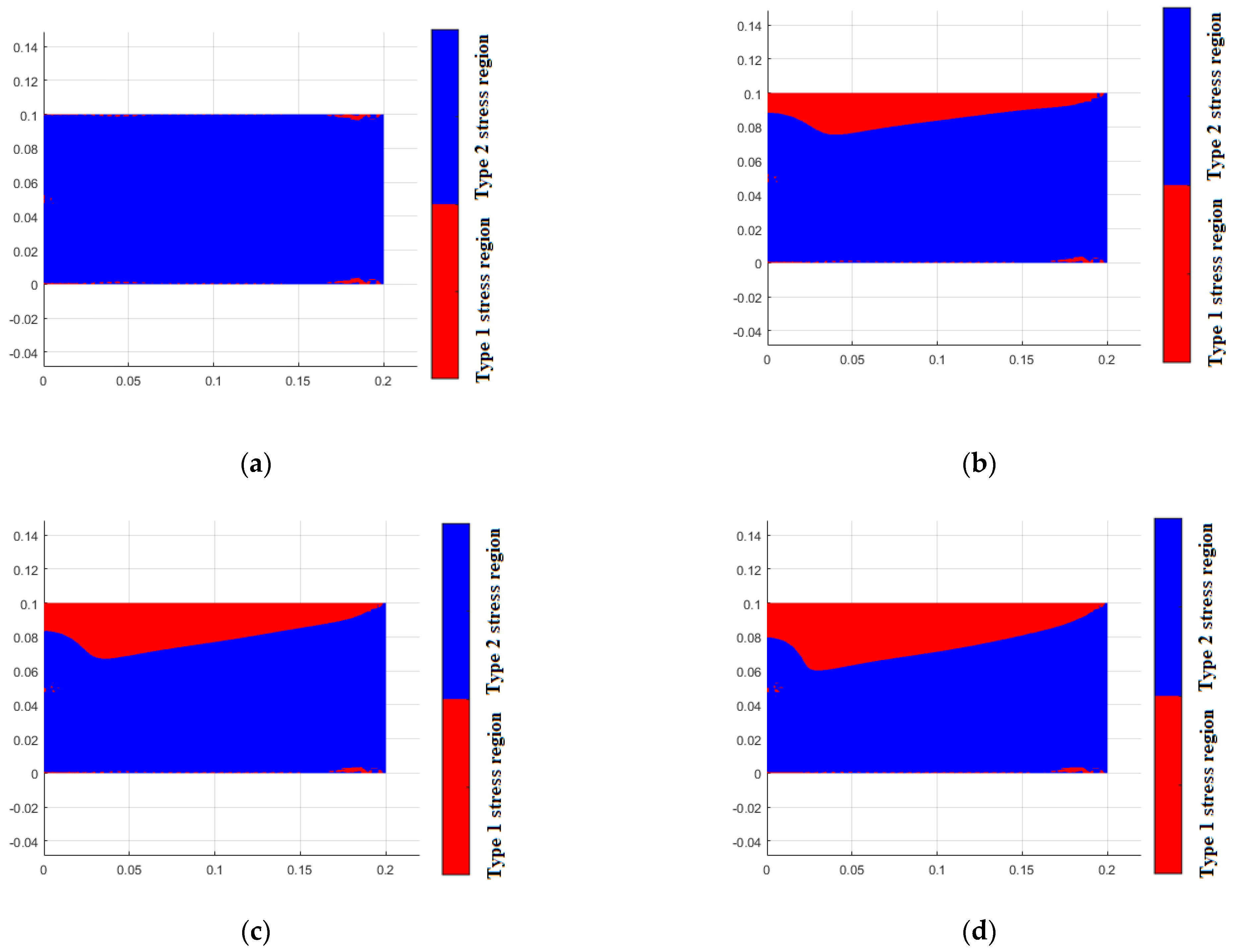

3.2. Model Verification

3.2.1. Verification by Degeneration to Tension–Compression Isotropic Modulus Model

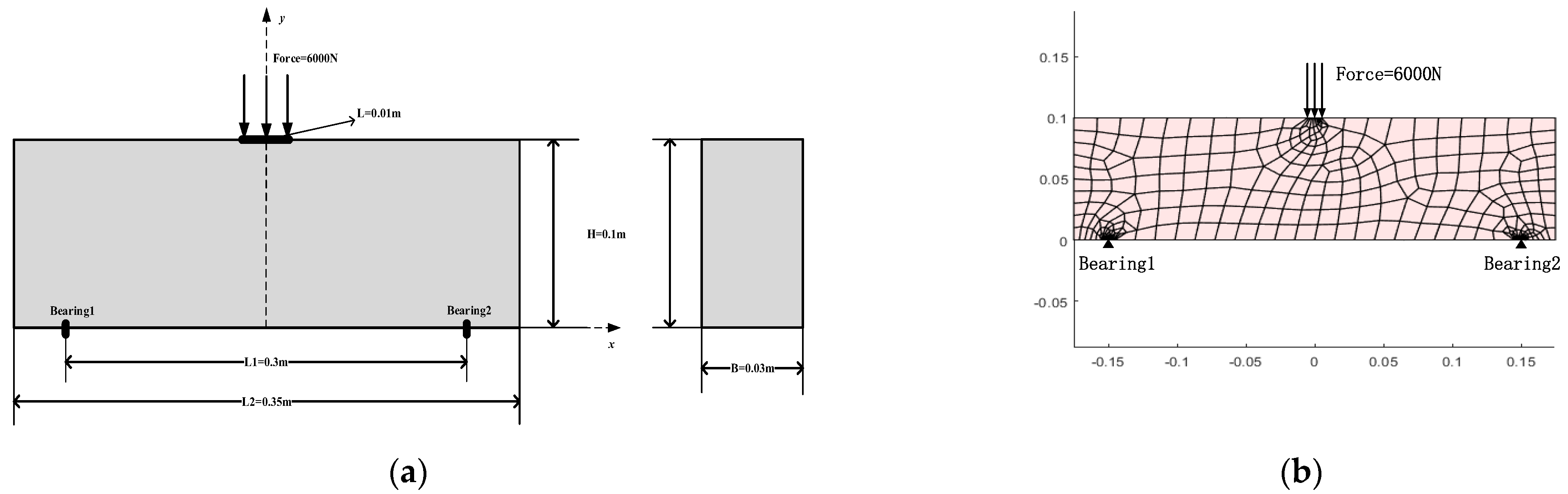

3.2.2. Verification with Other Methods of Different Moduli in Tensile and Compressive

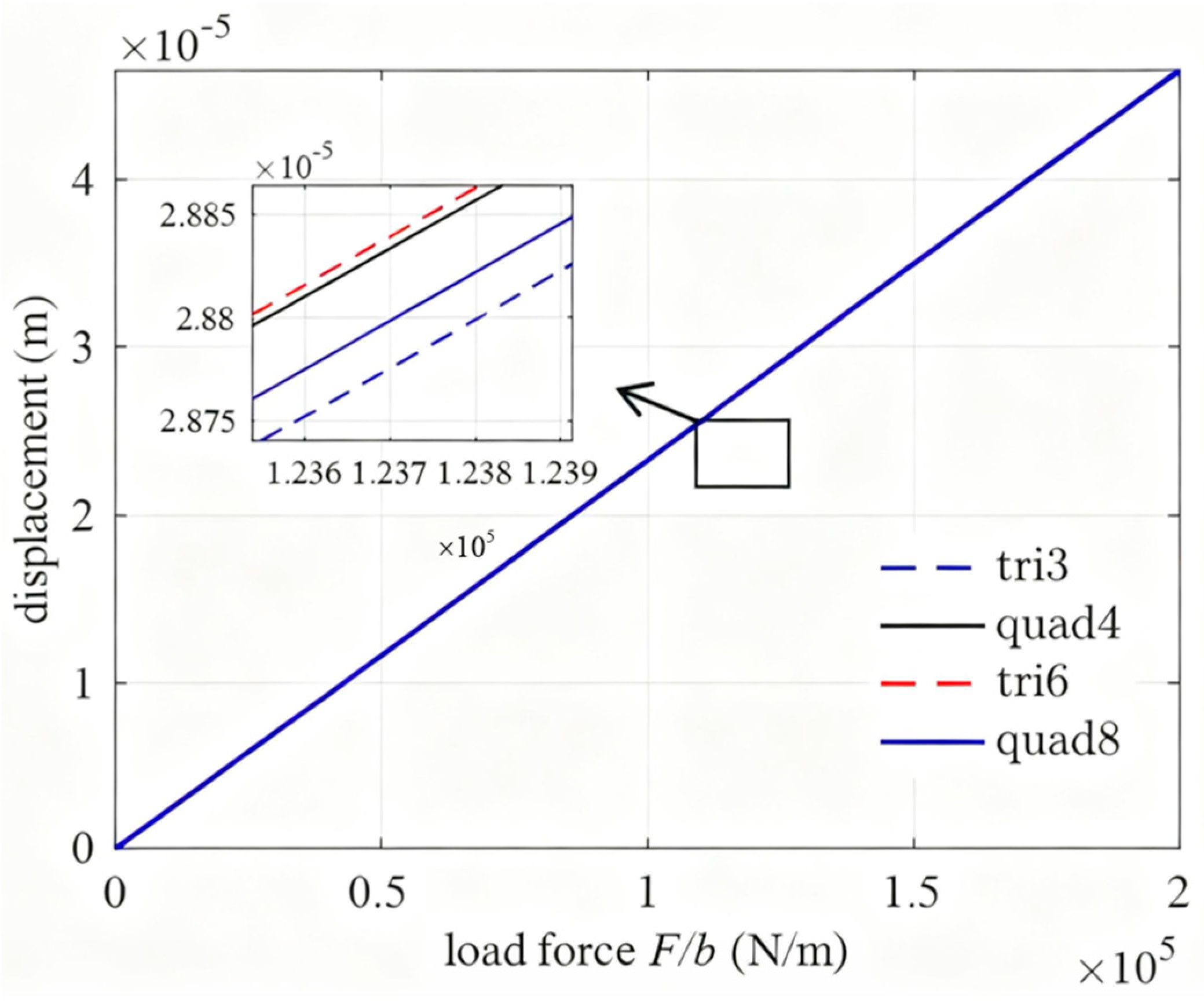

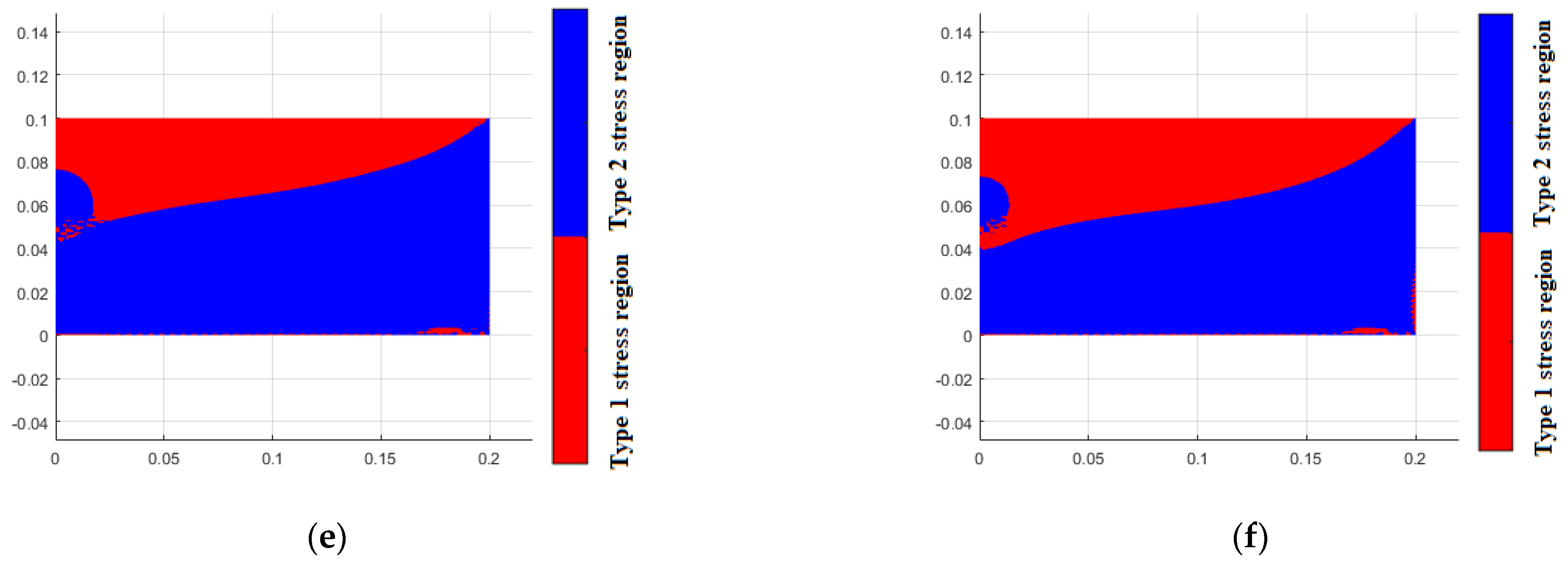

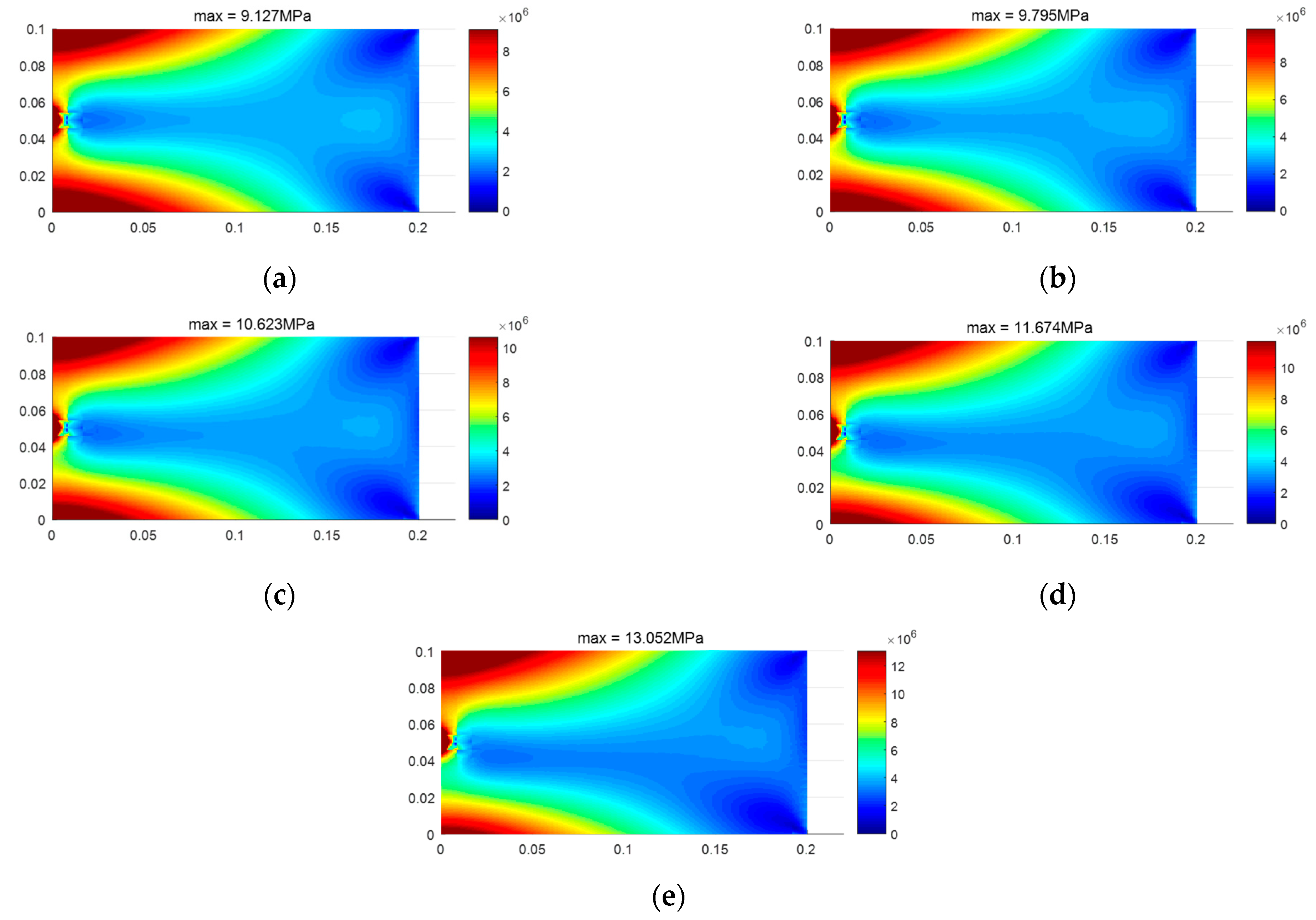

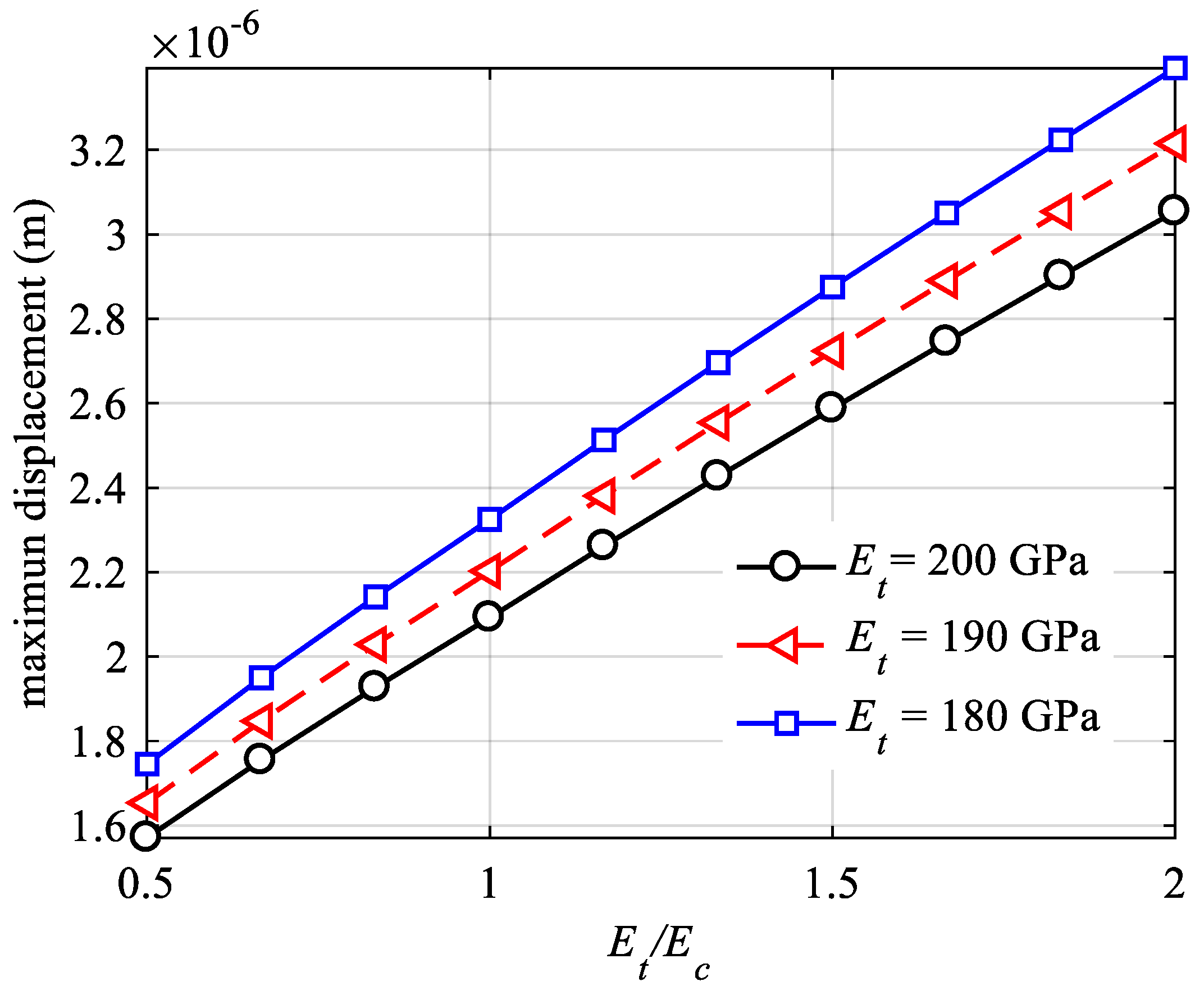

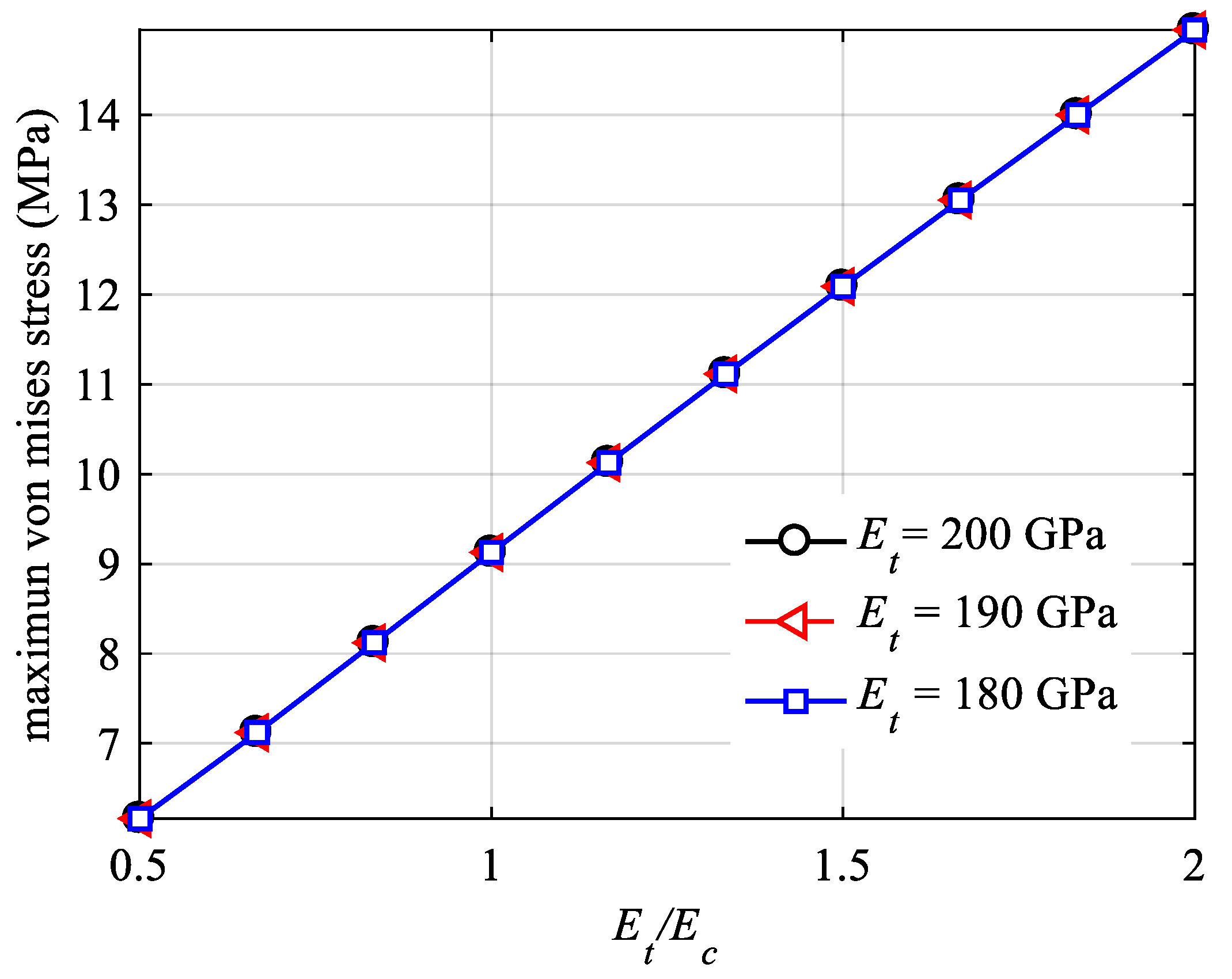

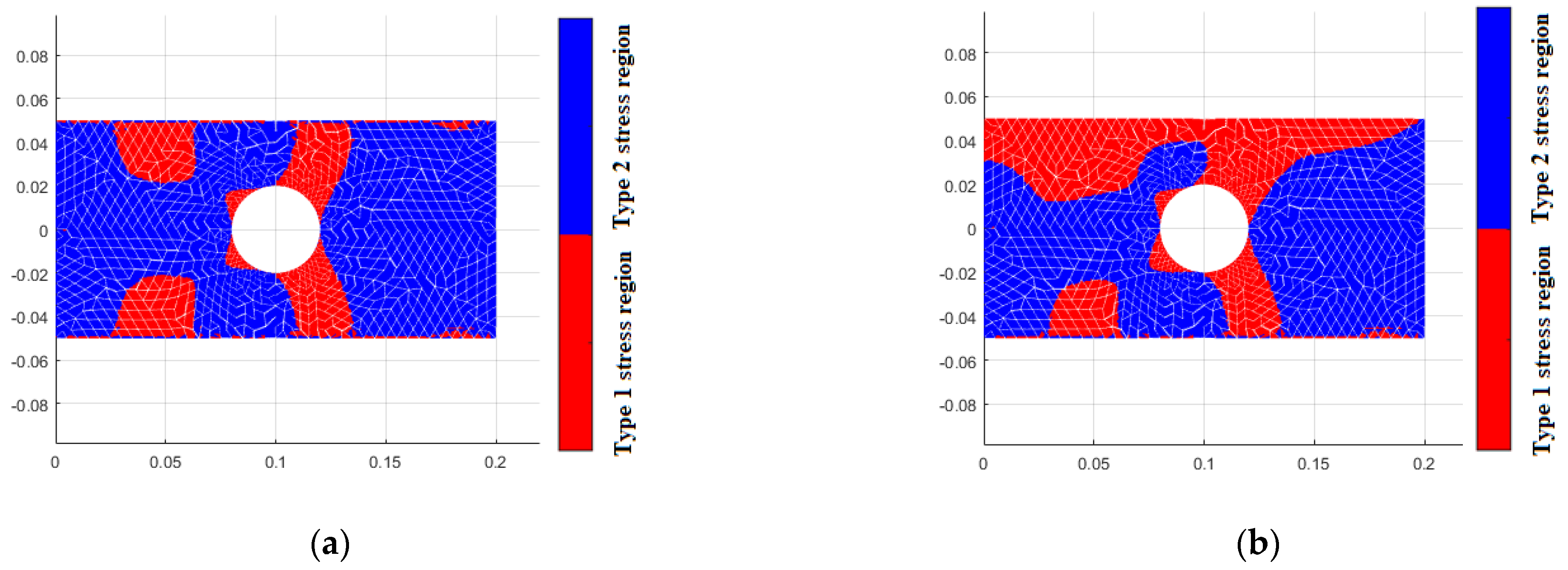

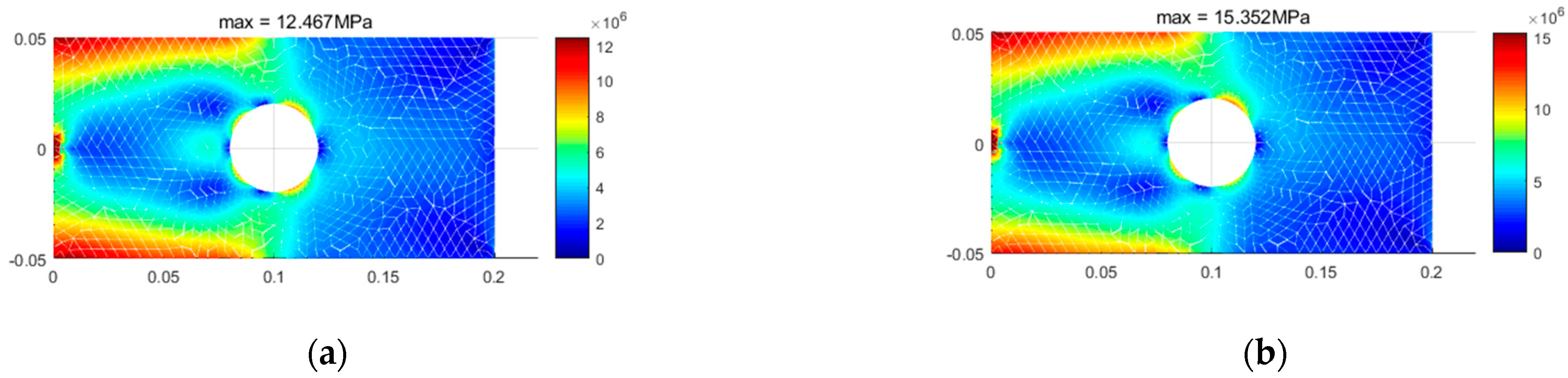

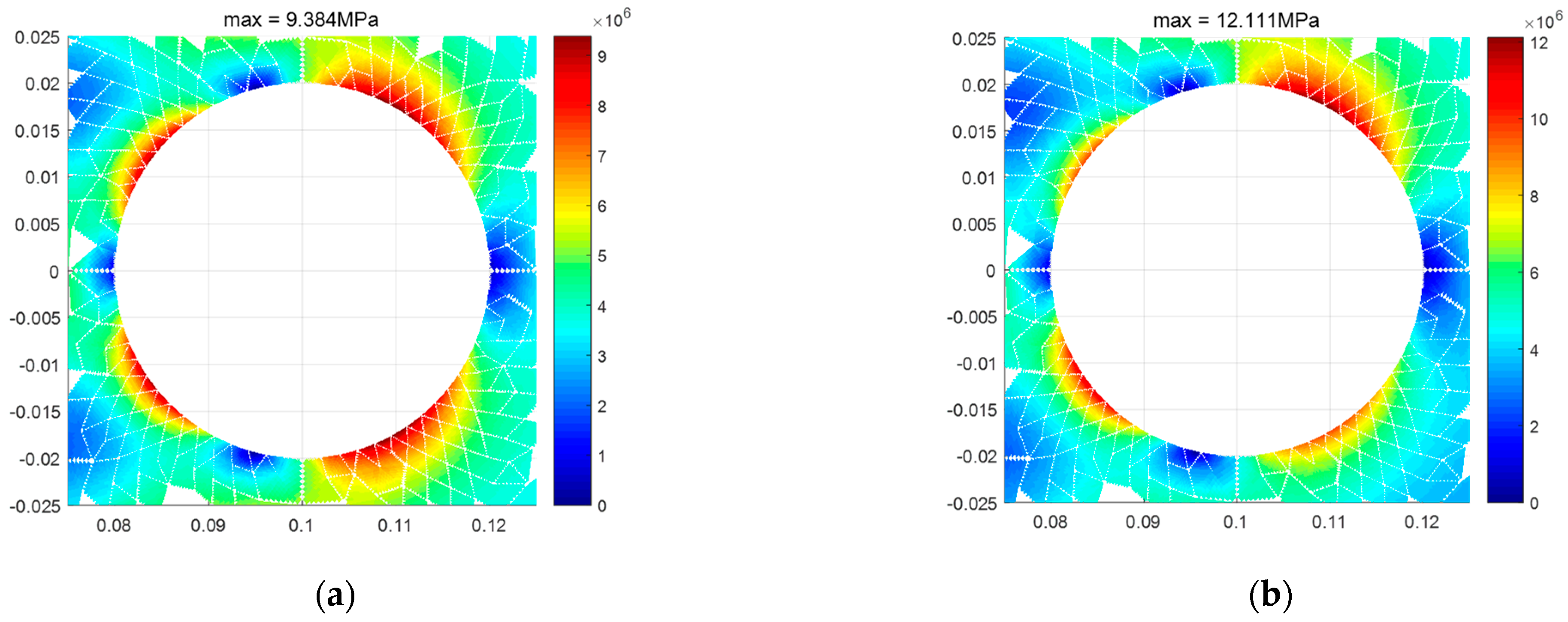

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beskopylny, A.; Meskhi, B.; Kadomtseva, E.; Strelnikov, G. Transverse Impact on Rectangular Metal and Reinforced Concrete Beams Taking into Account Bimodularity of the Material. Materials 2020, 13, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xu, H.; Sun, P. Performance analysis of bimodular simply supported beams based on the deformation decomposition method. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2023, 30, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yao, C.; Yu, Y.; Hong, Z.; Zhi, M.; Wang, X. Mesoporous piezoelectric polymer composite films with tunable mechanical modulus for harvesting energy from liquid pressure fluctuation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 6760–6765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viet, N.V.; Zaki, W.; Umer, R. Analytical investigation of an energy harvesting shape memory alloy–piezoelectric beam. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2020, 90, 2715–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Inoue, K.; Kawai, M.; Xue, Y. Modeling of nonlinear response in loading-unloading tests for fibrous composites under tension and compression. Compos. Struct. 2019, 207, 894–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, M.M.; Currey, J.D.; Weiner, S.; Shahar, R. Are tensile and compressive Young’s moduli of compact bone different? J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2009, 2, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Ma, Y. A full-scale topology optimization method for surface fiber reinforced additive manufacturing parts. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2022, 401, 115632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bert, C.W. Models for fibrous composites with different properties in tension and compression. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 1977, 99, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destrade, M.; Gilchrist, M.D.; Motherway, J.; Murphy, J. Bimodular rubber buckles early in bending. Mech. Mater. 2010, 42, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor-Artigues, M.-M.; Roure-Fernández, F.; Ayneto-Gubert, X.; Bonada-Bo, J.; Pérez-Guindal, E.; Buj-Corral, I. Elastic Asymmetry of PLA Material in FDM-Printed Parts: Considerations Concerning Experimental Characterisation for Use in Numerical Simulations. Materials 2019, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.M. Stress-strain relations for materials with different moduli in tension and compression. AIAA J. 2012, 15, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambartsumyan, S.A. Different Modulus Theory of Elasticity; Moscow Science Publications: Moscow, Russia, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.-T.; Pei, X.-X.; Sun, J.-Y.; Zheng, Z.-L. Simplified theory and analytical solution for functionally graded thin plates with different moduli in tension and compression. Mech. Res. Commun. 2016, 74, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, R.H. Strength of materials, part 2, advanced theory and problems: By S. Timoshenko, second edition. J. Frankl. Inst. 1941, 232, 393. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.M. Apparent Flexural Modulus and Strength of Multimodulus Materials. J. Compos. Mater. 1976, 10, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bert, C.; Gordaninejad, F. Transverse shear effects in bimodular composite laminates. J. Compos. Mater. 1983, 17, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambartsumyan, S.A. Elasticity Theory of Different Moduli; Wu, R.F., Zhang, Y.Z., Eds.; China Railway: Beijing, China, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, J.N.; Chao, W.C. Nonlinear bending of bimodular-material plates. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1983, 19, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinno, R.; Greco, F. Damage evolution in bimodular laminated composites under cyclic loading. Compos. Struct. 2001, 53, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-W.; Chen, C.C. Asymmetric vibration and dynamic stability of bimodulus thick annular plates. Comput. Struct. 1989, 31, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, J.-Y.; Dong, J.; He, X.-T. One-Dimensional and Two-Dimensional Analytical Solutions for Functionally Graded Beams with Different Moduli in Tension and Compression. Materials 2018, 11, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.-T.; Li, W.-M.; Sun, J.-Y.; Wang, Z.-X. An elasticity solution of functionally graded beams with different moduli in tension and compression. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2018, 25, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, G. Analysis for the Canopy of Plane with the Theory of Extension Compression Elastic Modulus. J. Dalian Fish. Univ. 1997, 12, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, G.; Xianqiang, L. Analysis for the plate with the theory of different extension compression elastic modulis. Chin. J. Comput. Mech. 1998, 15, 448. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Lu, X.Q. Analysis of thin-shell structures based on bi-moduli theory. Eng. Mech. 2000, 17, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Meng, X.; Qu, C. Modeling of Bimodular Bone Specimen under Four-Point Bending Fatigue Loading. Materials 2022, 15, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.M.; Chen, T.; Yao, W.J. Progresses in elasticity theory with different modulus in tension and compression and related FEM. Mech. Eng. 2004, 26, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Z.; Wang, D.; Chen, T. Numerical study for load-carrying capacity of beam-column members having different Young′s moduli in tension and compression. Int. J. Model. Identif. Control 2009, 7, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.-J.; Zhang, C.-H.; Jiang, X.-F. Nonlinear Mechanical Behavior of Combined Members with Different Moduli. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2006, 7, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, X.; Zheng, J.; Jiang, C. Topology optimization for structures with bi-modulus material properties considering displacement constraints. Comput. Struct. 2023, 276, 106952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, M.; Montáns, F.J. Bi-modulus materials consistent with a stored energy function: Theory and numerical implementation. Comput. Struct. 2020, 229, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Guo, X. A new computational framework for materials with different mechanical responses in tension and compression and its applications. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2016, 100, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebecca, G.; Giulia, M.; Luisa, R. A Bi-Modulus Material Model for Bending Test on NHL3.5 Lime Mortar. Materials 2023, 16, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.X.; Zheng, J.L.; Li, Q.; Wen, P.H. Fracture analysis for bi-modular materials. Eur. J. Mech. A/Solids 2020, 80, 103904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.-T.; Wang, X.-G.; Sun, J.-Y. Application of perturbation-variation method in large deformation bimodular cylindrical shells: A comparative study of bending theory and membrane theory. Appl. Math. Model. 2024, 129, 448–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Du, Z.; Chung, H.; Tang, S.; Guo, Y.; Chen, B.; Guo, X. Finite deformation analysis of bi-modulus thermoelastic structures and its application in wrinkling prediction of membranes. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2024, 427, 117034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Ye, Z. Analytic elasticity solution of bi-modulus beams under combined loads. Appl. Math. Mech. 2015, 36, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medri, G. A Nonlinear Elastic Model for Isotropic Materials with Different Behavior in Tension and Compression. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 1982, 104, 26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambartsumyan, S.A.; Khachatryan, A.A. The basic equations of the theory of elasticity for materials with different tensile and compressive stiffness. Russ. Electr. Eng. 1966, 1, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Yunzhen, Z.; Zhifeng, W. The finite element method for elasticity with different moduli in tension and compression. Comput. Struct. Mech. Appl. 1989, 6, 236–246. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.T.; Zheng, Z.L.; Sun, J.Y.; Li, Y.M.; Chen, S.L. Convergence analysis of a finite element method based on different moduli in tension and compression. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2009, 46, 3734–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan-Lin, C. Approximate Elasticity Solution of Bending-compression Column with Different Tension-compression Moduli. J. Chongqing Univ. 2008, 31, 339–343. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W.H.; Peng, Z.J.; Meng, S.H.; Xu, C.H.; Yi, F.J.; Du, S.Y. GWFMM model for bi-modulus orthotropic materials: Application to mechanical analysis of 4D-C/C composites. Compos. Struct. 2016, 150, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, B. An analysis of longitudinal vibration of bimodular rod via smoothing function approach. J. Sound Vib. 2008, 317, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, H.W. An efficient algorithm for mechanical analysis of bimodular truss and tensegrity structures. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2013, 70, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Zheng, C.; Song, X.; Lv, S.; Yu, H.; Zhang, J.; Cabrera, M.B.; Liu, H. Mechanical analysis of asphalt pavement based on bimodulus elasticity theory. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 301, 124084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iandiorio, C.; Serenella, R.; Salvini, P. A Combined Approach of Experimental Testing and Inverse FE Modelling for Determining Homogenized Elastic Properties of Membranes and Plates. Eng. Proc. 2025, 85, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.; Pan, Q.; Jin, J.; Zheng, J.; Wen, P. Continuous constitutive model for bimodulus materials with meshless approach. Appl. Math. Model. 2018, 66, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, L.; Huang, Y. Micro- and Macromechanical Properties of Materials; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Ye, J. Numerical analysis of bending property of bi-modulus materials and a new method for measurement of tensile elastic modulus. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2023, 15, 2539–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tri3 | Error | Quad4 | Error | Tri6 | Error | Quad8 | Error | Plane82 | Error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.8970 | −77.72% | 1.4998 | −62.75% | 3.4915 | −13.29% | 3.6047 | −10.48% | 3.7389 | −7.14% |

| 4 | 2.8582 | −29.02% | 3.5700 | −11.34% | 3.9786 | −1.19% | 3.9963 | −0.75% | 4.0219 | −0.11% |

| 8 | 3.6056 | −10.45% | 3.8848 | −3.52% | 4.0058 | −0.52% | 4.0189 | −0.19% | 4.0305 | 0.10% |

| 16 | 3.8903 | −3.38% | 3.9833 | −1.07% | 4.0149 | −0.29% | 4.0246 | −0.05% | 4.0299 | 0.08% |

| 24 | 3.9541 | −1.80% | 4.0044 | −0.55% | 4.0166 | −0.25% | 4.0252 | −0.03% | 4.0287 | 0.05% |

| 32 | 3.9786 | −1.19% | 4.0124 | −0.35% | 4.0171 | −0.23% | 4.0252 | −0.03% | 4.0278 | 0.03% |

| 40 | 3.9907 | −0.89% | 4.0163 | −0.25% | 4.0173 | −0.23% | 4.0251 | −0.04% | 4.0271 | 0.01% |

| 48 | 3.9976 | −0.72% | 4.0185 | −0.20% | 4.0173 | −0.23% | 4.0249 | −0.04% | 4.0265 | 0.00% |

| Ref [50] | Present | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tri3 | Quad4 | Tri6 | Quad8 | ||||||

| Error | Error | Error | Error | ||||||

| Same Modulus | 3.5 × 10−5 | 3.432 × 10−5 | 1.95% | 3.518 × 10−5 | 0.51% | 3.734 × 10−5 | 6.69% | 3.712 × 10−5 | 6.05% |

| Different Modulus | 6 × 10−5 | 5.710 × 10−5 | 4.83% | 5.852 × 10−5 | 2.46% | 6.136 × 10−5 | 2.27% | 6.114 × 10−5 | 1.9% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, C.; Wang, F.; Wang, T.; Zhao, L.; Qian, P.; Li, M.; Dai, Z.; Zeng, S. A Finite Element Study of Bimodulus Materials with 2D Constitutive Relations in Non-Principal Stress Directions. Materials 2025, 18, 5126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225126

Dong C, Wang F, Wang T, Zhao L, Qian P, Li M, Dai Z, Zeng S. A Finite Element Study of Bimodulus Materials with 2D Constitutive Relations in Non-Principal Stress Directions. Materials. 2025; 18(22):5126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225126

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Chao, Fei Wang, Tongtong Wang, Long Zhao, Penghui Qian, Mingfeng Li, Zhenglong Dai, and Shan Zeng. 2025. "A Finite Element Study of Bimodulus Materials with 2D Constitutive Relations in Non-Principal Stress Directions" Materials 18, no. 22: 5126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225126

APA StyleDong, C., Wang, F., Wang, T., Zhao, L., Qian, P., Li, M., Dai, Z., & Zeng, S. (2025). A Finite Element Study of Bimodulus Materials with 2D Constitutive Relations in Non-Principal Stress Directions. Materials, 18(22), 5126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225126