3.1. Problem Definition and Design Variables

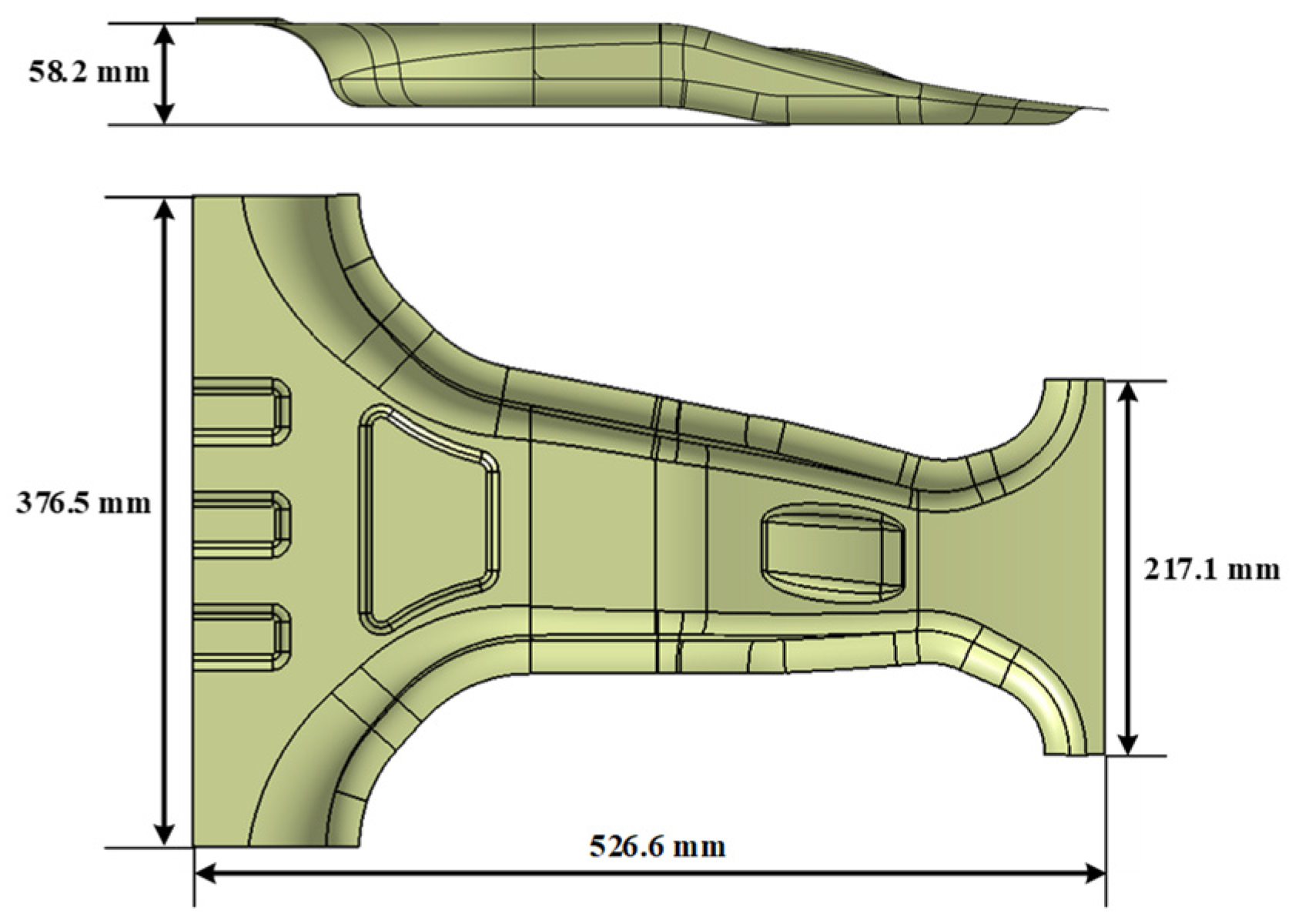

The target structure for optimization in this study was a lab-scale CFRP B-pillar, which was modeled using CATIA V5 based on the geometry of typical automotive B-pillar components, as shown in

Figure 5. For comparative evaluation with conventional steel body panels, a woven thermoset CFRP prepreg from TORAY was selected as the material for the lab-scale CFRP B-pillar. Six CFRP prepreg layers of 0.2 mm thickness per ply were stacked to achieve the same thickness as a DP590 steel panel of 1.2 mm thickness. The design variables used in this study were the fiber orientation angles of the six prepreg plies. Based on the feasible manufacturing and orthotropic behavior of the woven composites, the allowable ply angles were discretized in 15° increments as follows:

The total number of combinations of design variables was 6

6 (=46,656), representing all possible lay-up configurations within the specified angle set. Two objective functions were defined to maximize the structural strength and failure safety simultaneously. Specifically, two criteria were evaluated at a prescribed deformation level corresponding to a punch stroke of 14 mm: (a) maximum load (structural strength) and (b) maximum failure safety (MoS), which were calculated using the modified Tsai-Wu failure criterion. The Tsai-Wu failure criterion was employed to evaluate the failure behavior of each lay-up configuration under bending. This strength-based failure model considers the combined effects of in-plane stresses and provides a scalar failure index (FI), which is calculated as follows:

Expanded into in-plane components, the equation becomes:

The corresponding strength tensors,

Fi and

Fij are defined using the tensile, compressive, and shear strengths of the material as follows:

where

Xt,

Xc,

Yt, and

Yc are the tensile and compressive strengths in the fiber and transverse directions, respectively, and

S is the in-plane shear strength. The material properties of the CFRP are listed in

Table 1.

Table 2 lists the strength values obtained from the technical datasheet of the manufacturer.

Although the Tsai–Wu index (FI = 1) identifies the onset of failure, it does not provide a quantitative measure of safety margin when FI < 1 [

25,

26]. To address this, a safety factor

R was introduced as the ratio of the allowable stress to the actual stress, enabling a continuous measure of structural reliability [

27]:

For the Tsai-Wu criterion, the safety factor

R is determined by solving the quadratic relationship obtained from the polynomial form of the criterion:

The analytical solution of this equation is:

where the coefficients

a and

b are defined according to the Tsai-Wu strength tensor and the in-plane stress components as:

Finally, the margin of safety (MoS) is defined as the surplus capacity beyond the applied load, given by:

This metric offers intuitive insight: for instance, MoS = 1 indicates that the structure can withstand twice the applied load, while MoS = −0.5 implies failure unless the load is reduced by at least 50%. It should be noted that Equation (25) was derived under the plane stress assumption, and the Tsai-Wu coefficients (Fi, Fij) were obtained based on an orthotropic material model for the CFRP lamina. The derivation steps presented above ensure the mathematical consistency between the general Tsai-Wu criterion and the scalar failure metric implemented in the FE simulation.

Table 1.

Mechanical properties of CFRP laminate for structure analysis [

28].

Table 1.

Mechanical properties of CFRP laminate for structure analysis [

28].

| Property | Symbol | Value |

|---|

| Elastic Modulus in fiber direction (GPa) | | 65.01 |

| Elastic Modulus in transverse direction (GPa) | | 65.01 |

| Poisson’s ratio in 1–2 | | 0.13 |

| Shear Modulus in 1–2 (GPa) | | 12.69 |

| Shear Modulus in 2–3 (GPa) | | 1.38 |

| Shear Modulus in 1–3 (GPa) | | 1.38 |

| Mass Density (g/cm2) | | 1.52 |

Table 2.

Strength of CFRP.

Table 2.

Strength of CFRP.

| Property | Symbol | Value |

|---|

| Tensile stress in fiber direction (MPa) | | 638 |

| Compressive stress in fiber direction (MPa) | | 494 |

| Tensile stress in transverse direction (MPa) | | 633 |

| Compressive stress in transverse direction (MPa) | | 491 |

| Shear strengh (MPa) | | 106 |

The deformation condition used in this study was based on the mechanical characteristics of automotive body panels with 1.2 mm-thick steel sheets, which generally exhibit elastic load responses up to 1 kN from the results of a previous study [

7]. To provide a comparable reference to this benchmark while also enabling the evaluation of failure behavior in CFRP lay-ups, punch strokes of 12, 14, and 16 mm were initially examined. For each case, the margin of safety (MoS) and maximum load were evaluated for ten randomly selected lay-up configurations, as summarized in

Table 3.

The results showed that the load of all selected configurations exceeded 1 kN at a punch stroke of 14 mm, and the MoS as a failure safety indicator showed meaningful differences with various distributions. By contrast, no failure was predicted at a stroke of 12 mm for any configuration, which was inadequate for the evaluation of failure-related characteristics. Furthermore, several lay-ups at a stroke of 12 mm produced loads below the 1 kN threshold, which restricted the evaluation of structural performance and made the condition unsuitable for comparative analysis. At a punch stroke of 16 mm, all lay-up configurations were predicted to fail, making it difficult to evaluate the trade-offs between the two objective functions, because every solution collapsed into a failure state. Therefore, a punch stroke of 14 mm was selected as the evaluation condition for lay-up optimization in this study because it represented a suitable distribution of values for strength assessment and damage progression.

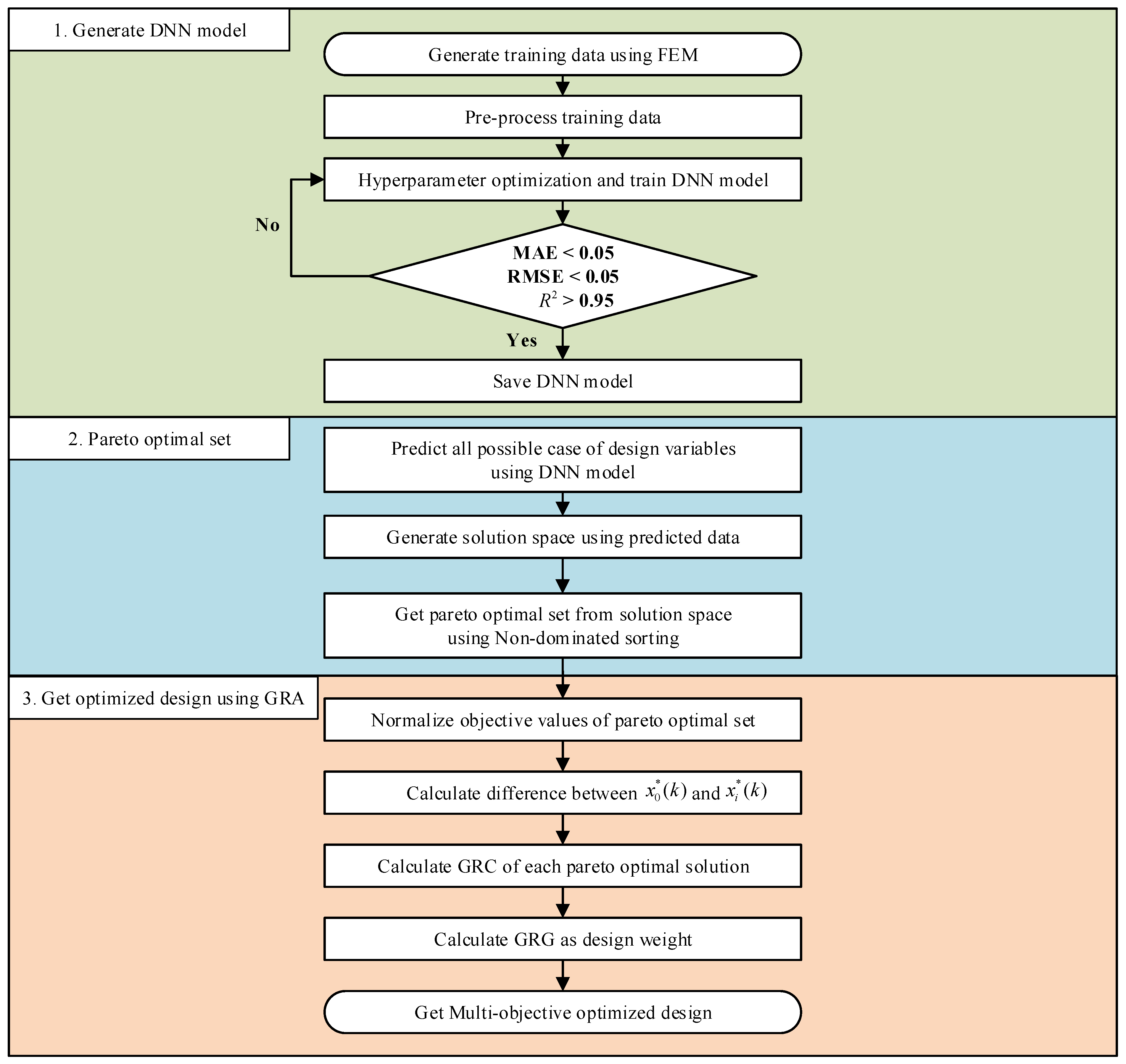

3.2. Multi-Objective Optimization

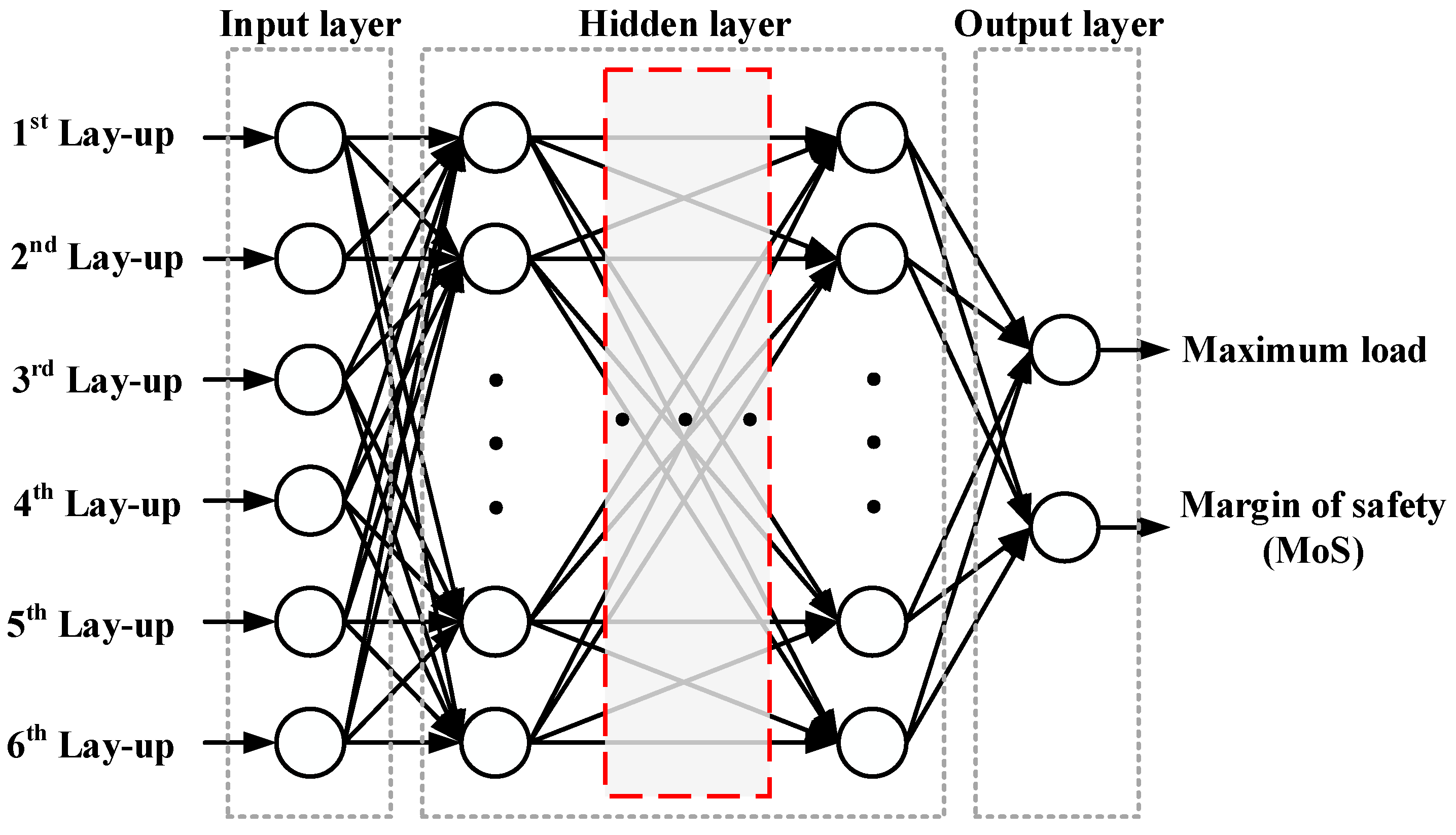

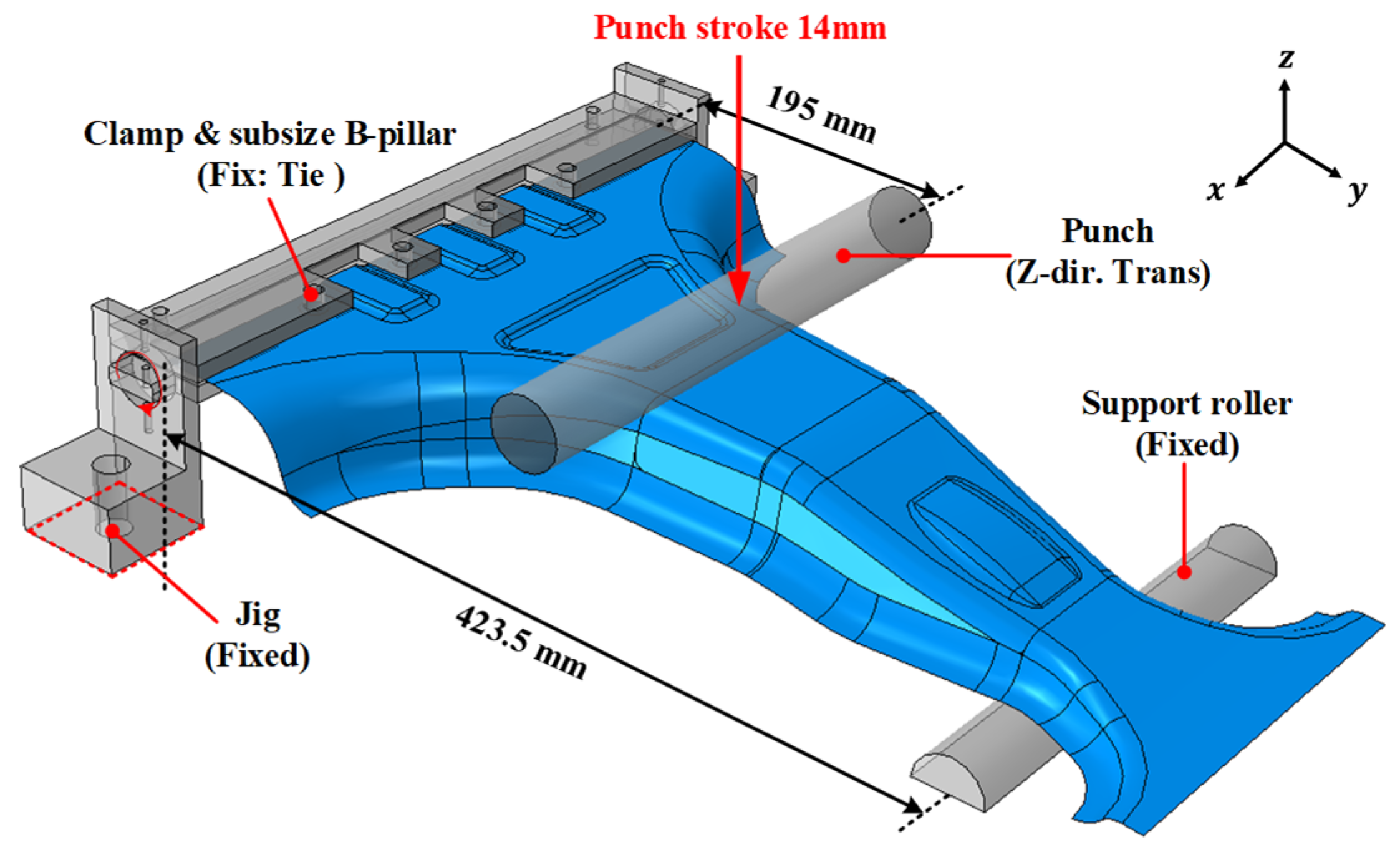

To construct the deep neural network (DNN) surrogate model, a finite element analysis (FEA) was conducted for 2000 randomly selected lay-up configurations to evaluate their structural strength and failure safety. The maximum load and MoS values for each lay-up configuration of the lab-scale CFRP B-pillar were obtained from the FEA under bending conditions, simulating a side impact, as illustrated in

Figure 6. A linear static analysis of bending was adopted as an experimental and numerical surrogate to reproduce the local bending and compressive loads acting on the B-pillar during a side collision. This simplified bending model allows a controlled and repeatable evaluation of bending-dominated behavior while maintaining a direct correlation with the deformation mode of the full-scale component. The boundary conditions were defined to replicate the laboratory setup, with both supports fixed in the vertical direction and the punch displacement-controlled, ensuring consistency between the numerical and experimental results. The position of the applied load was based on the bumper height of the test vehicle [

29,

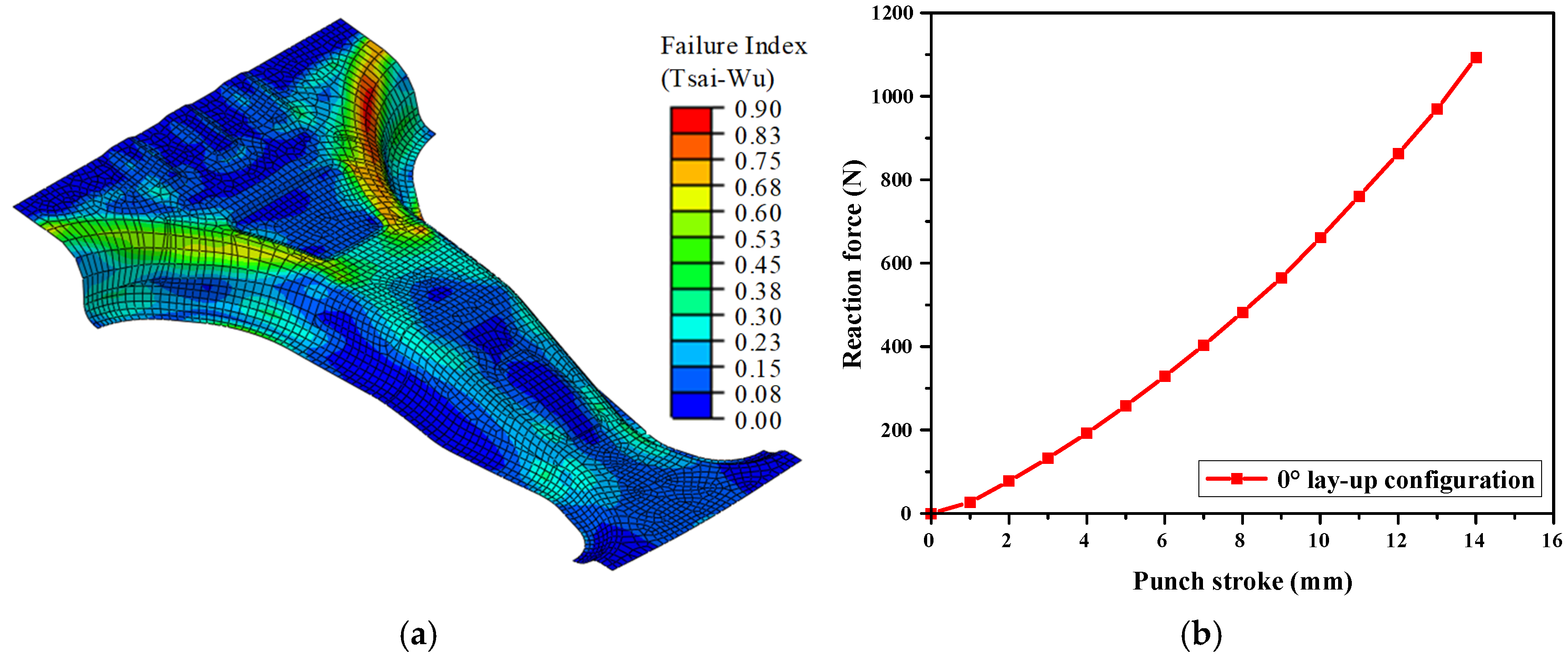

30]. The FEA model utilized 3D shell elements, and the two objective values, the maximum load and margin of safety (MoS), were normalized to the range of 0–1 using min-max normalization to improve the DNN learning performance. The representative FEA results for the 0° lay-up configuration, including the failure index distribution and stroke–force responses, are illustrated in

Figure 7. This example demonstrate how the maximum load and MoS are extracted from the simulations and subsequently used as training data for the DNN surrogate model.

The dataset was divided into three subsets using random sampling: 70% for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing. The learning rate for the DNN model was set to 0.001, and the ReLU activation function was used in combination with the Adam optimizer. The maximum number of training epochs was set to 300 with early stopping to prevent overfitting when the validation loss plateaued. The final DNN model structure consisted of five hidden layers, each with 1000 nodes. This configuration was selected based on a systematic hyperparameter tuning process that evaluated various layer and node combinations to balance accuracy, generalization, and computational efficiency. Each candidate architecture was trained and validated using the same dataset, and its performance was quantitatively assessed through mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), coefficient of determination (

R2), and validation loss trends. Deeper networks tended to overfit the training data, while shallower ones exhibited insufficient nonlinear mapping capability and lower predictive accuracy. The selected architecture achieved stable convergence, minimized generalization error, and provided consistent predictions across multiple training iterations. The complete model is presented in

Table 4. This architecture yielded excellent prediction accuracy, with MAE of 0.023, RMSE of 0.038, and R

2 of 0.978 for the test set, as presented in

Table 5.

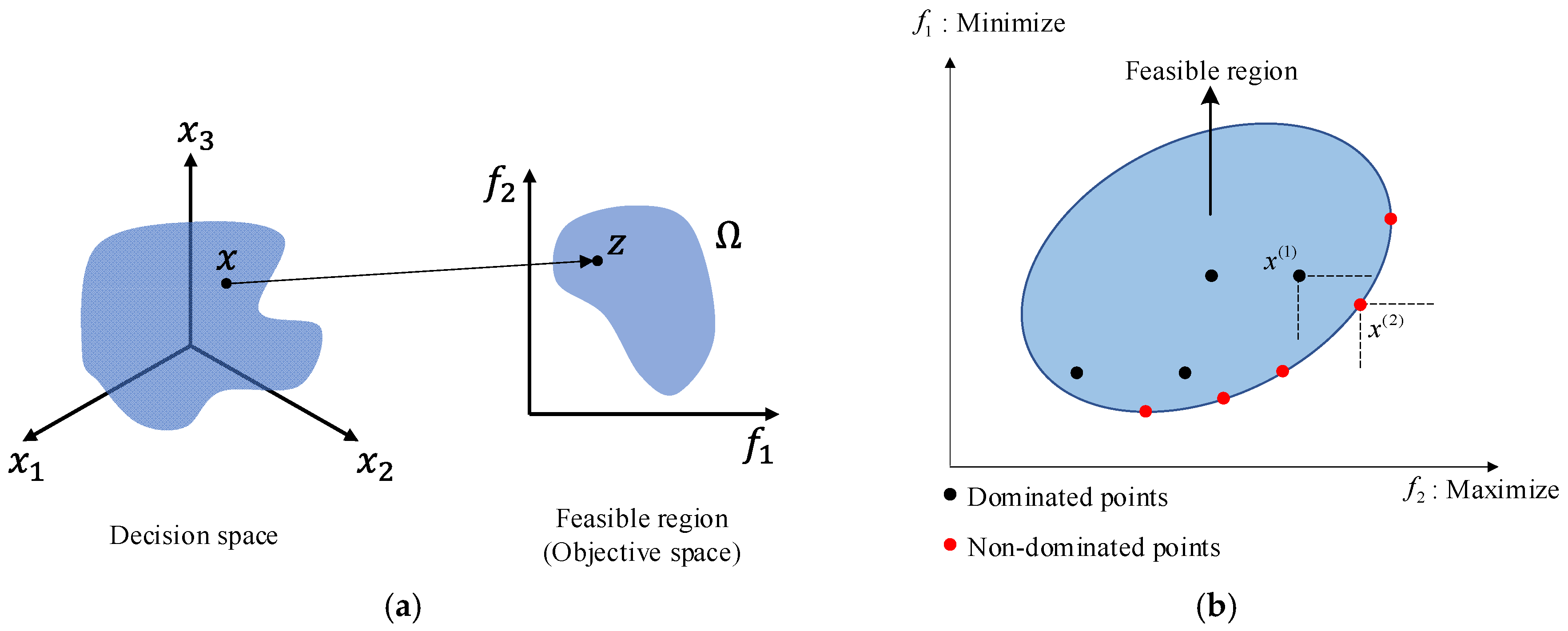

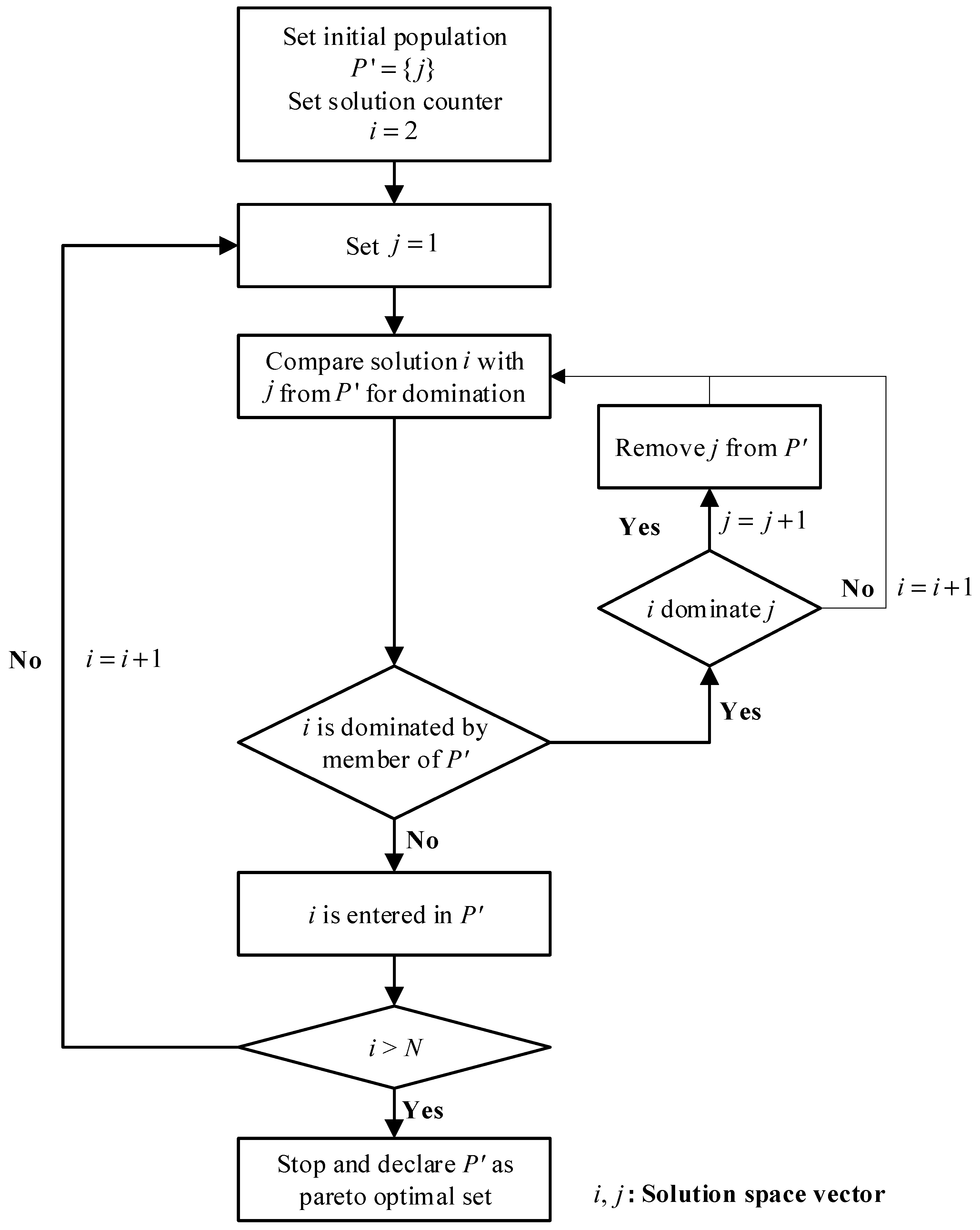

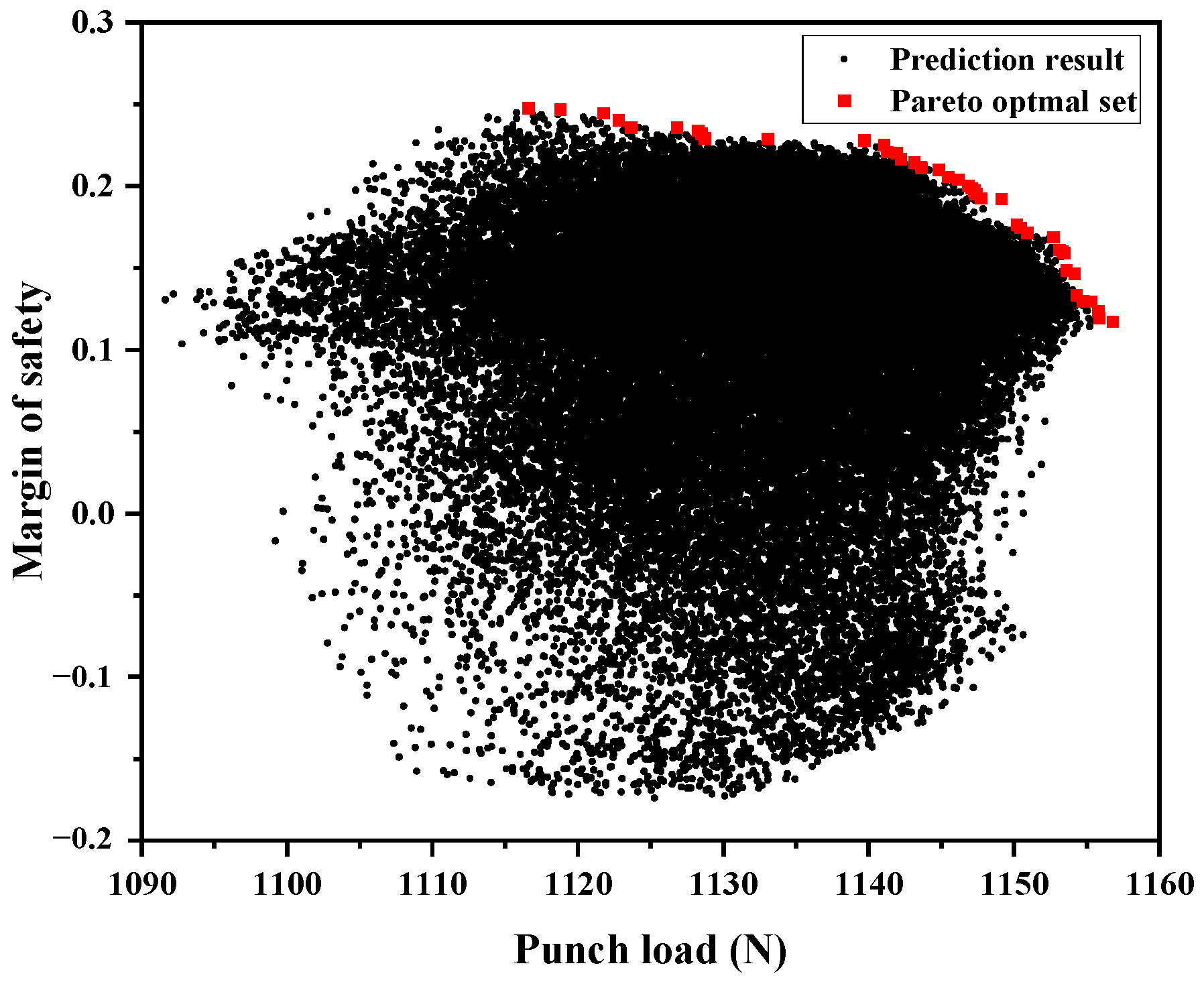

Using the trained DNN surrogate model, 46,656 possible lay-up configurations were evaluated to predict the load and MoS values. Subsequently, these predictions were used to generate the full solution space, as shown in

Figure 8. From this space, 43 non-dominated solutions were identified using the Pareto sorting procedure described in

Figure 4, and the lay-up configurations are listed in

Table A1 in

Appendix A.

To determine the optimal design considering the weight factor of the designer for the multi-objective function, which means that the designer can evaluate the multi-objective function as a single objective value according to its relative importance, gray relational analysis (GRA) was applied to the Pareto optimal set. For each Pareto optimal solution, the objective values were normalized using the larger-the-better characteristic, and the gray relational coefficient (GRC) was calculated using Equation (13), where a distinguishing coefficient of

ξ = 0.5 was employed. The final gray relational grade (GRG) for each solution is then obtained from the summation of the GRCs with the assigned weights, as defined in Equation (14). Using this procedure, various weights can enable an optimal design reflecting the relative importance of the multi-objective function. Three different weights were applied to the two objective functions of structural strength and failure safety, where balanced design considered the same relative importance of structural strength and failure safety (

wLoad =

wMoS = 0.5), load-focused design considered the relative importance of structural strength as 0.9 (

wLoad = 0.9,

wMoS = 0.1), and MoS-focused design considered the relative importance of failure safety as 0.9 (

wMoS = 0.9,

wLoad = 0.1), such as (a) GRG

1 (Balanced design):

wLoad =

wMoS = 0.5, (b) GRG

2 (Load-focused design):

wLoad = 0.9,

wMoS = 0.1, and (c) GRG

3 (MoS-focused design):

wMoS = 0.9,

wLoad = 0.1. Optimal lay-up configurations for each case were determined as follows: (a) GRG

1 (Balanced): [0°/45°/60°/30°/0°/45°], (b) GRG

2 (Load-focused): [45°/45°/0°/0°/30°/45°], and (c) GRG

3 (MoS-focused): [0°/45°/60°/60°/60°/60°]. The GRG values corresponding to the determined lay-ups were 0.786, 0.950, and 0.950, respectively, as summarized in

Table A1 in

Appendix A. These values indicate that the selected lay-up configurations effectively achieved the optimized balance between structural strength and failure safety, which is consistent with the specified design intent.

The GRG values of the three lay-ups predicted by the proposed DNN-GRA optimization framework were verified using FEA. The predicted results were compared with simulation results to assess the accuracy of the DNN model. All errors between the predicted and simulated results were found to be within 5%, demonstrating a high prediction accuracy, as shown in

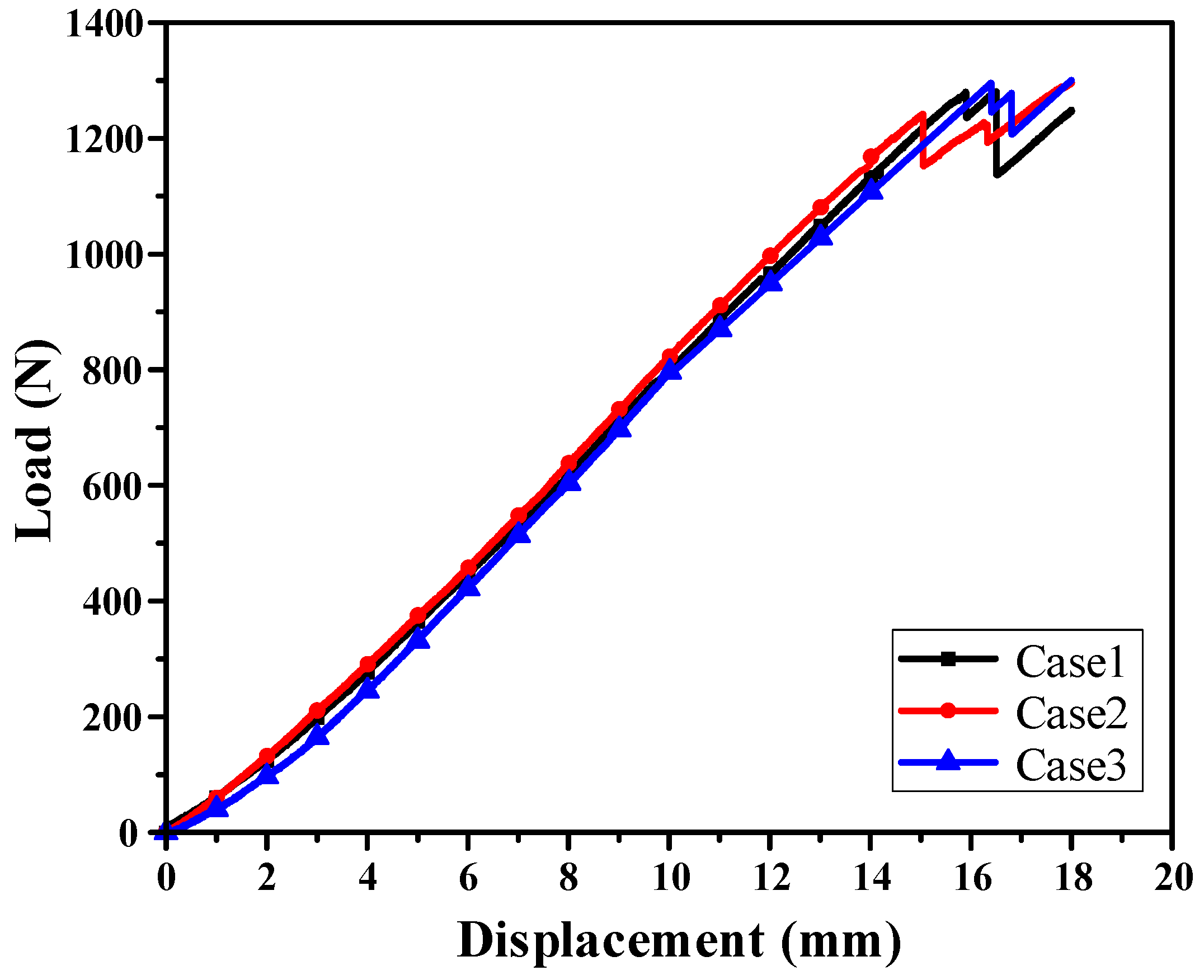

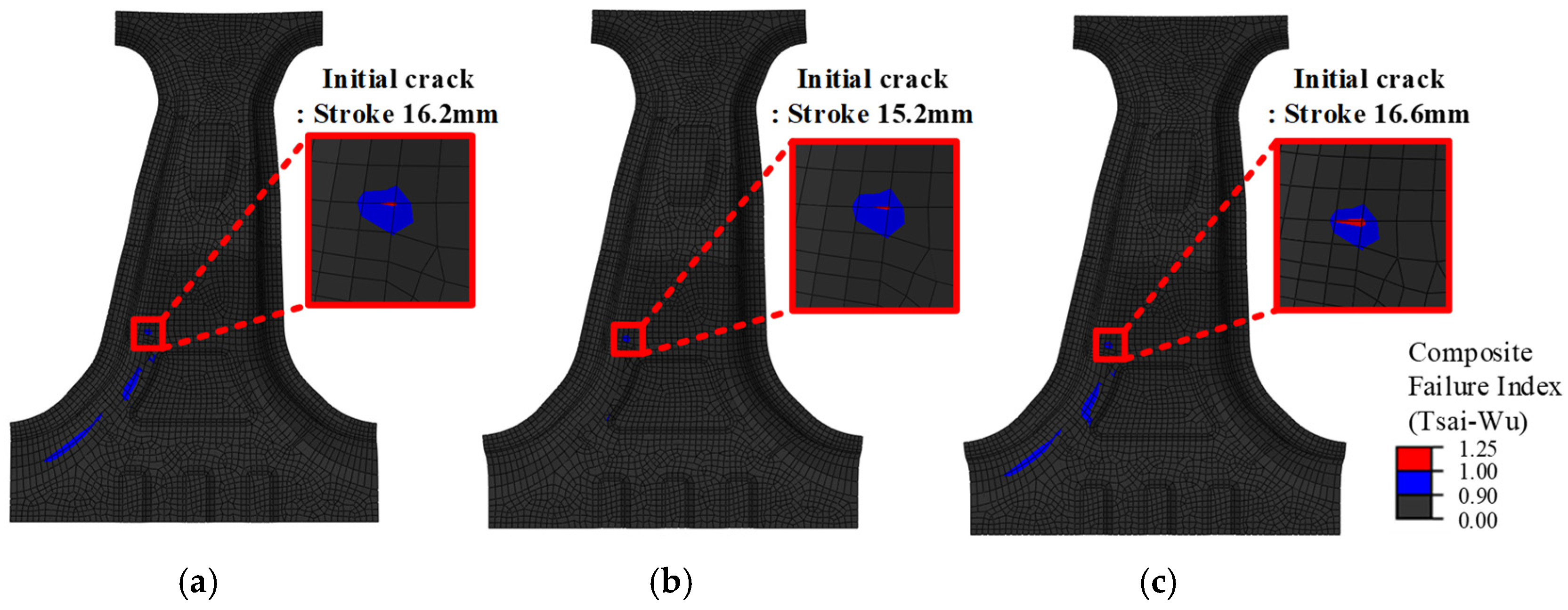

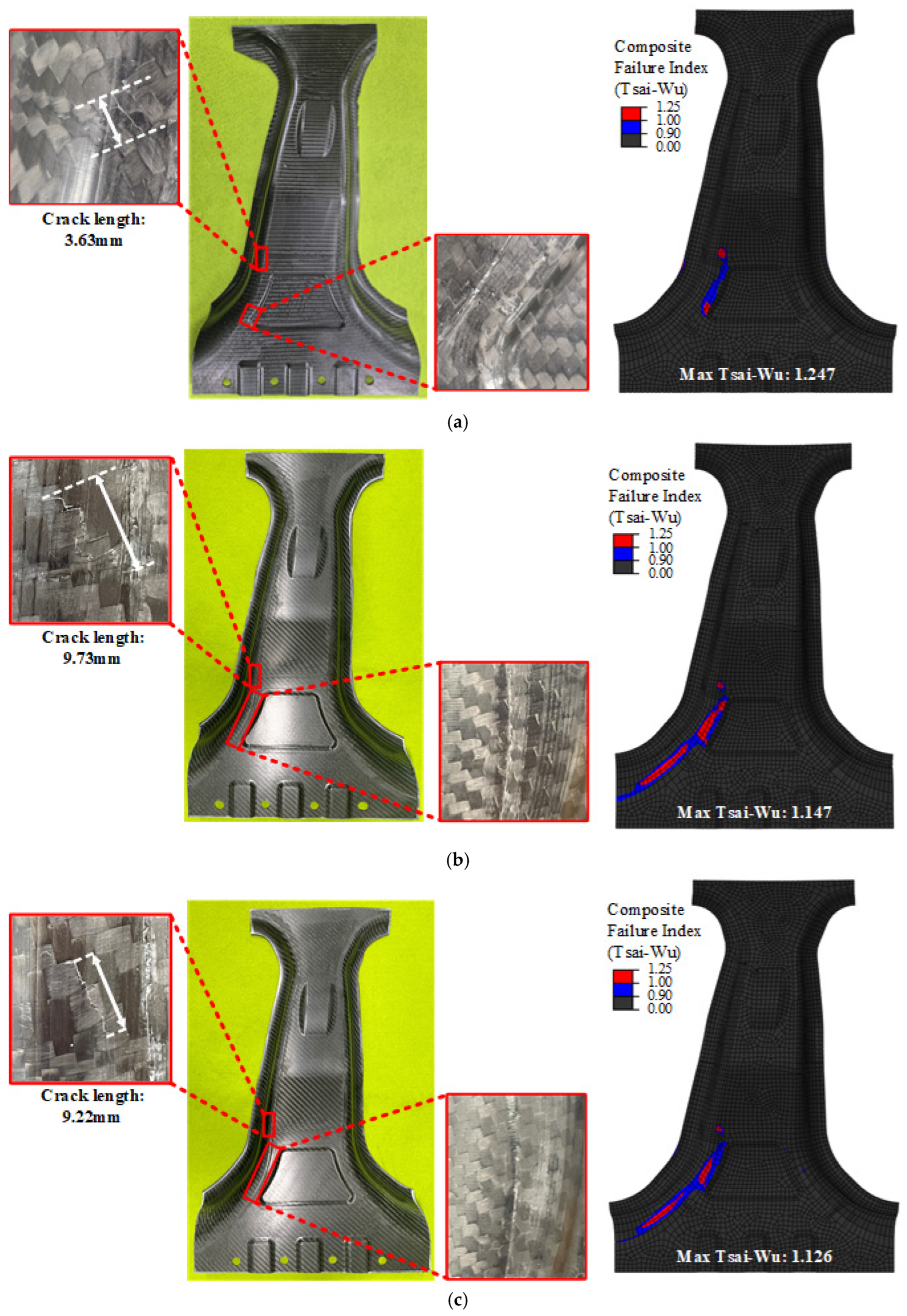

Table 6. The prediction error for the MoS was marginally higher than that for the maximum load, which can be attributed to the fact that the MoS was derived from the Tsai-Wu failure FI. Because the MoS involves a nonlinear combination of multiple stress components, small variations in the stress distribution can lead to amplified differences in the MoS value compared with the directly obtained load. A performance comparison of each case is shown in

Figure 9. The load-focused design (Case 2) exhibited the highest strength. Although the maximum load increased slightly compared with the other cases, this design achieved the highest overall strength value. This result indicates that a slight difference in ply orientation can yield a significant improvement in the load capacity. In contrast, the MoS-focused design (Case 3) showed the lowest strength but provided the most significant increase in MoS. The balanced design (Case 1) indicated simultaneous and moderate improvements in both objectives. The effectiveness of the GRA optimization with different design intents was confirmed from the above three case studies. Finally, lab-scale CFRP B-pillars were manufactured using optimized lay-up configuration, and bending tests were performed to validate the reliability and feasibility of the proposed multi-objective optimization.