Effect of Sample Thickness and Post-Processing on Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Titanium Alloy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Laboratory Experiments

- Group I—includes samples composed of Ti25Nb4Ta8Sn material without supplementary post-processing treatments.

- Group II—comprises Ti25Nb4Ta8Sn samples subjected to post-annealing to alleviate internal stresses.

- Group III—comprises specimens fabricated from Ti6Al4V material with annealing but without any additional post-processing treatments.

- Group IV—consists of Ti6Al4V samples subjected to annealing and etching of the surface and the removal of imperfectly fused powder grains through washing.

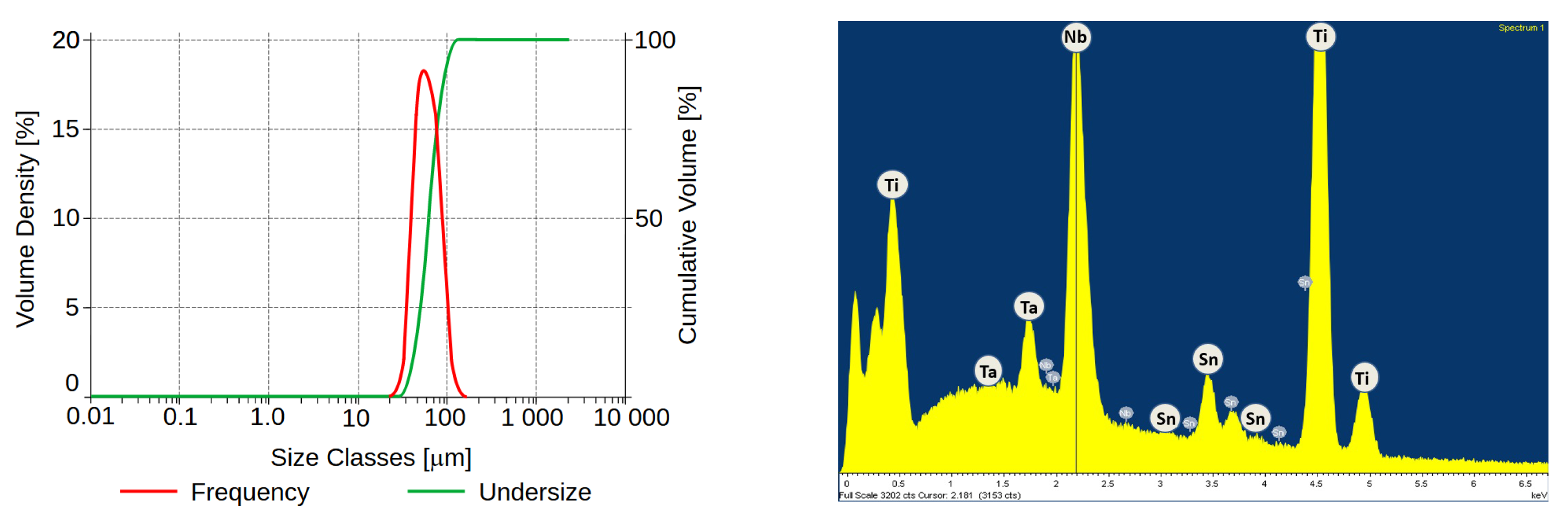

2.1. Preparation of Samples

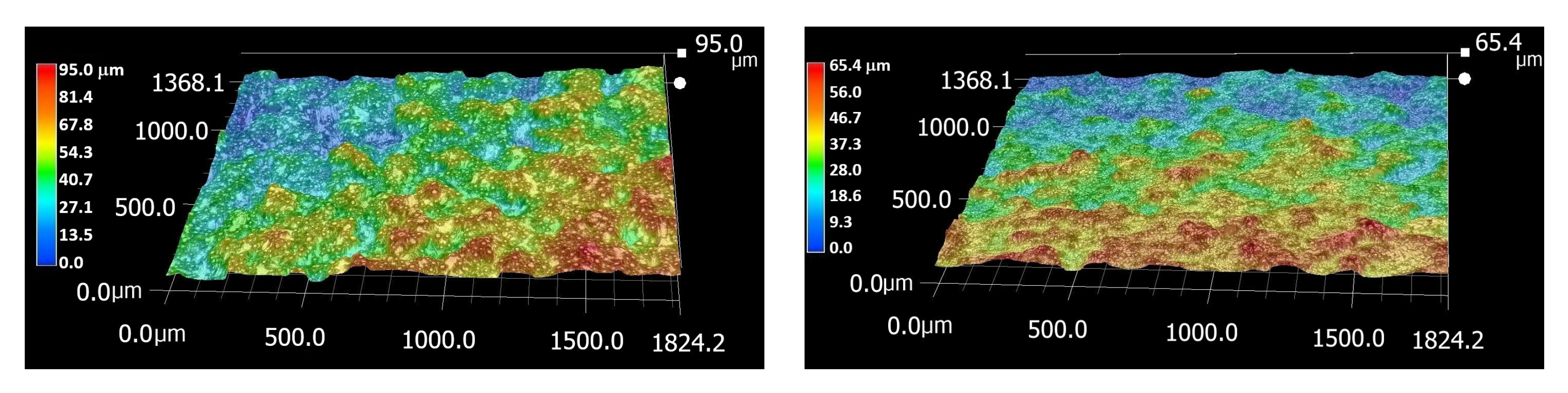

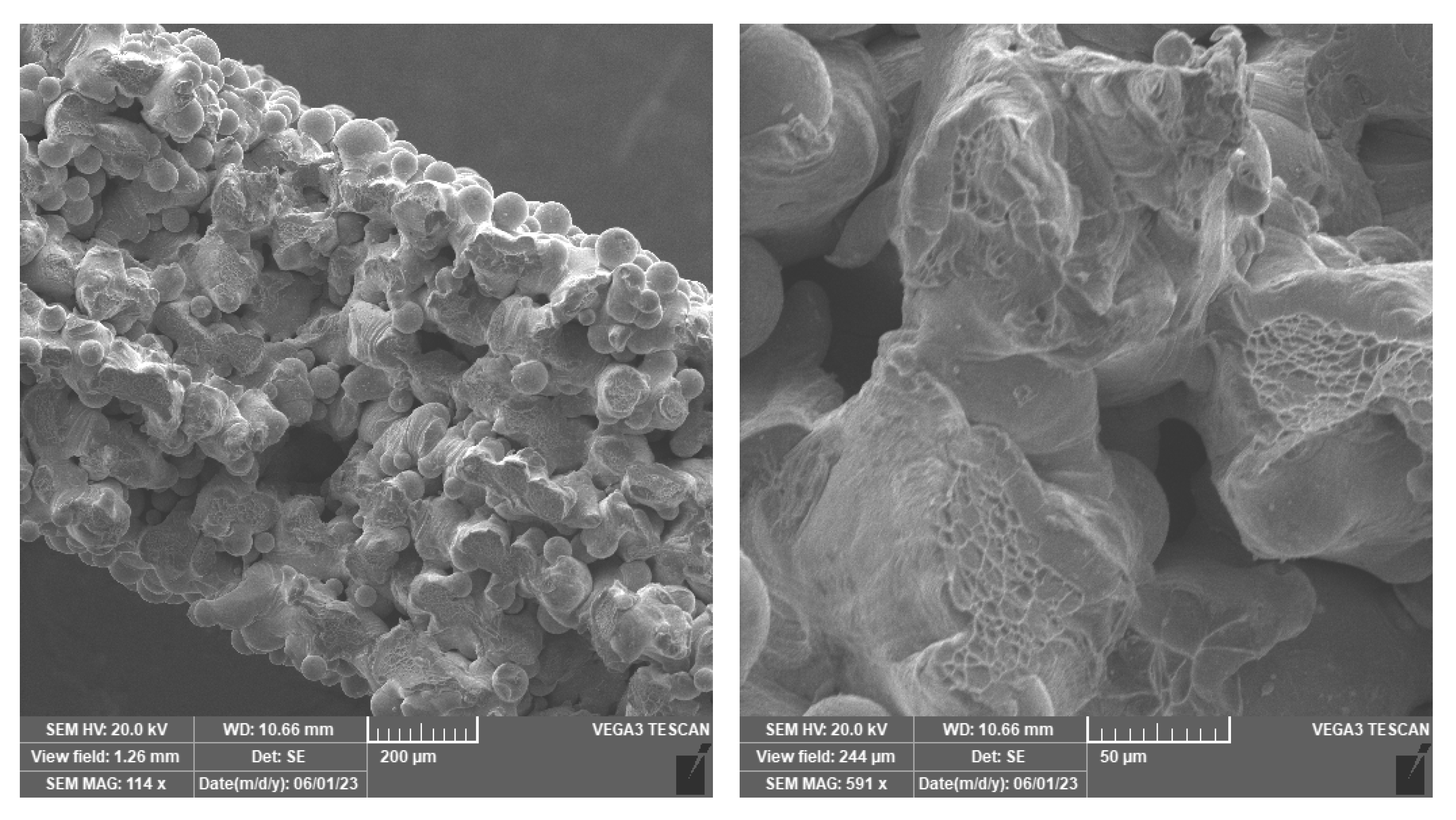

2.2. Surface Etching and Porosity

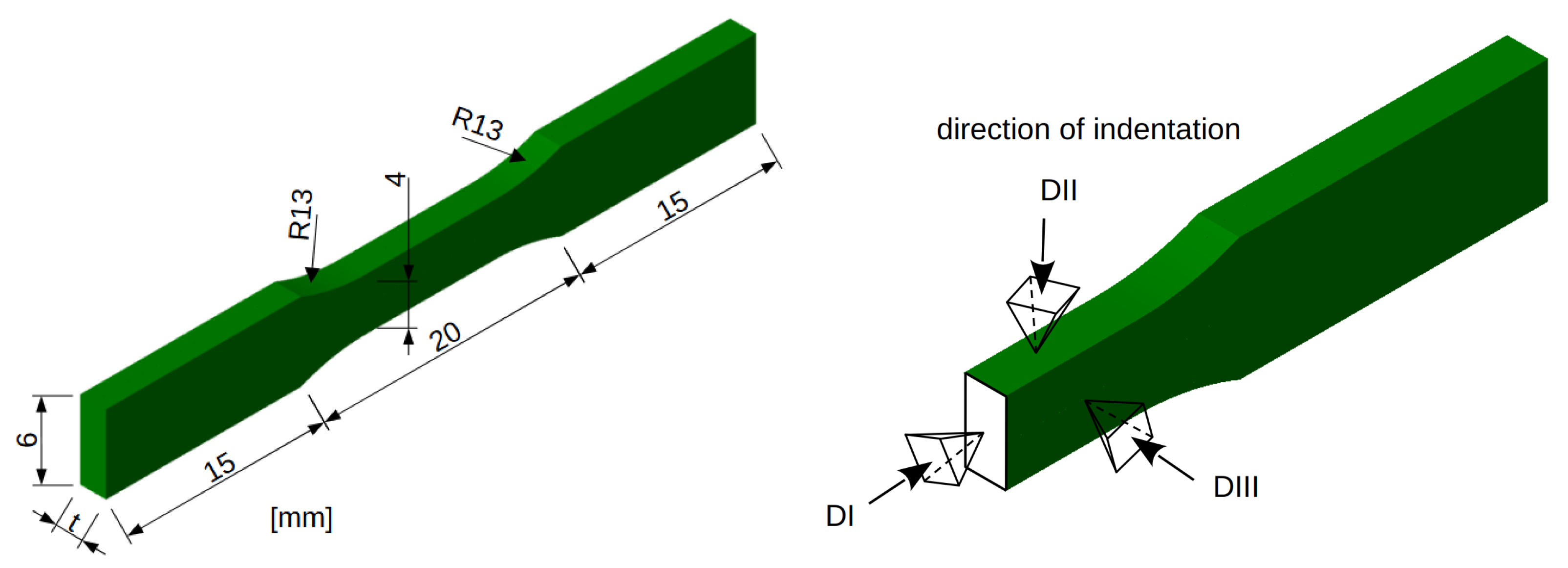

2.3. Mechanical Testing in Uniaxial Tension

2.4. Micromechanical Testing

3. Results and Discussion

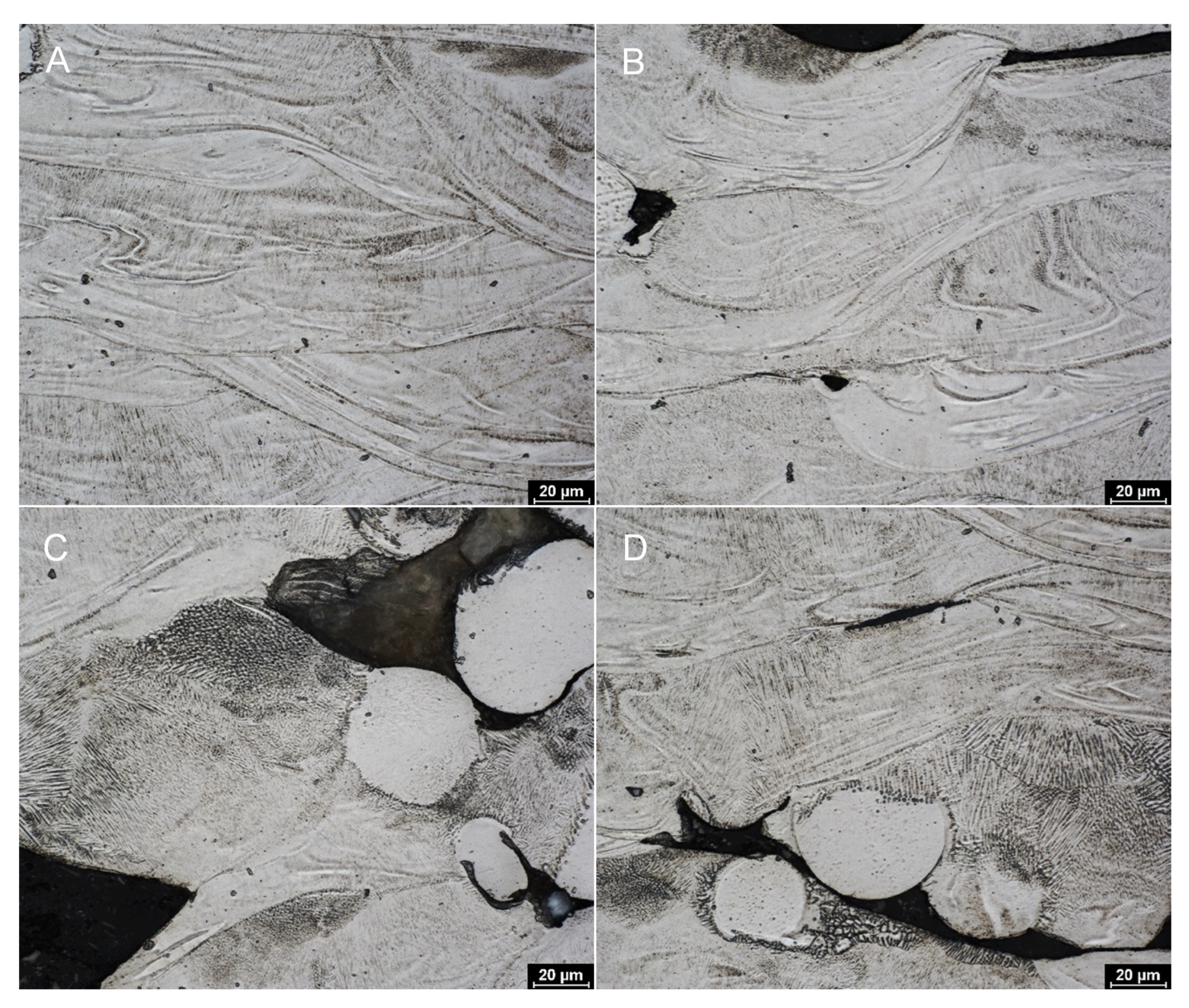

3.1. Metallography and Surface Etching

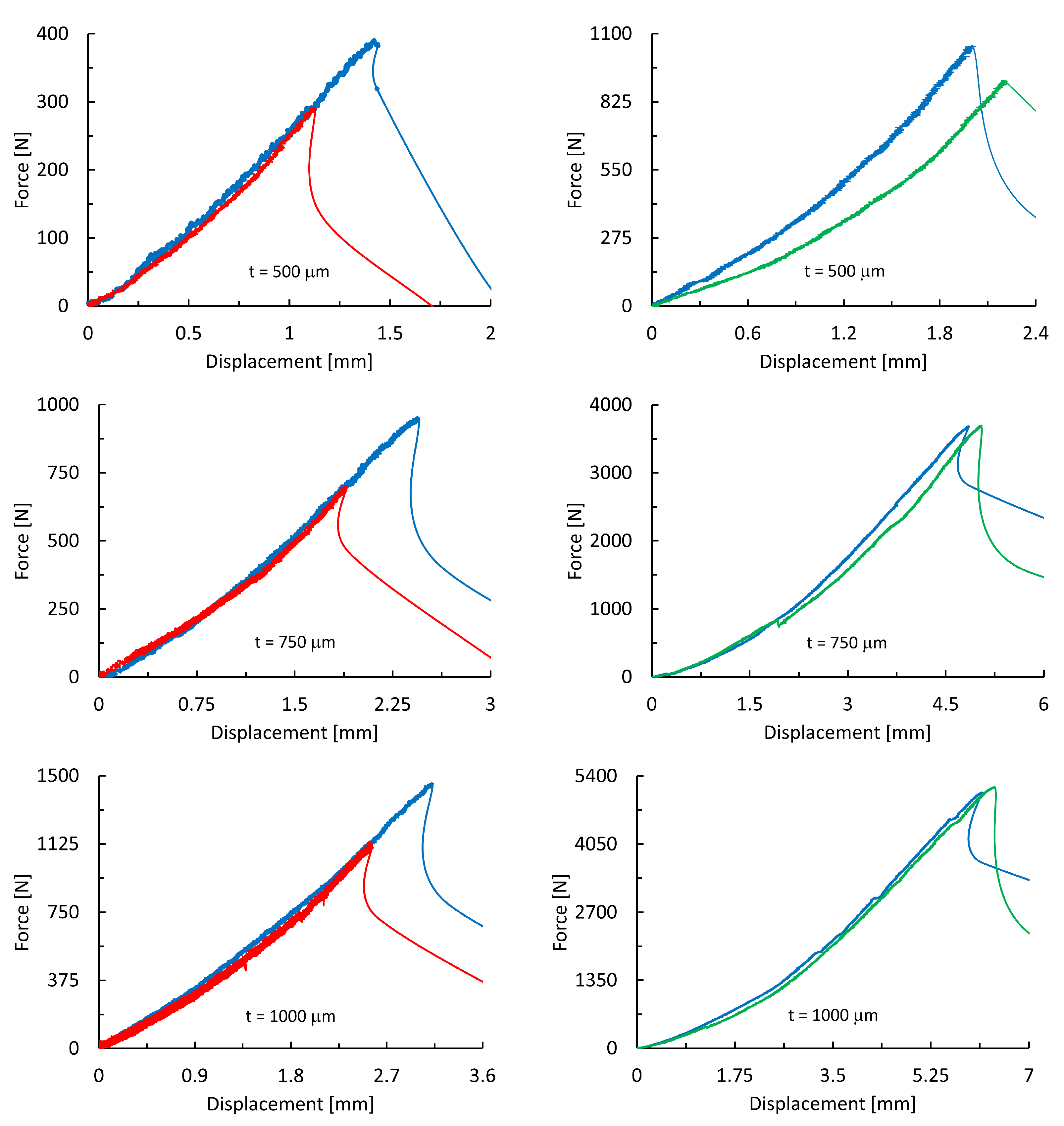

3.2. Result of Mechanical Testing

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Serrano, D.; Kara, A.; Yuste, I.; Luciano, F.; Ongoren, B.; Anaya, B.; Molina, G.; Diez, L.; Ramirez, B.; Ramirez, I.; et al. 3D Printing Technologies in Personalized Medicine, Nanomedicines, and Biopharmaceuticals. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Zhang, M.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, B.; Miao, Z.; Li, L.; Zheng, T.; Liu, P.; Duan, X. Application and Development of Modern 3D Printing Technology in the Field of Orthopedics. Biomed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, T.; Wang, Q.; Cai, H.; Li, W.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Z. Progressive 3D Printing Technology and Its Application in Medical Materials. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stihsen, C.; Springer, B.; Nemecek, E.; Olischar, B.; Kaider, A.; Windhager, R.; Kubista, B. Cementless Total Hip Arthroplasty in Octogenarians. J. Arthroplast. 2017, 32, 1923–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thillemann, M.; APedersen, l.B.; Mehnert, F.; Johnsen, S.P.; Soballe, K. Postoperative use of bisphosphonates and risk of revision after primary total hip arthroplasty: A nationwide population-based study. Bone 2010, 46, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pichardo, S.E.; van Merkesteyn, J.P. Bisphosphonate related osteonecrosis of the jaws: Spontaneous or dental origin? Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2013, 116, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pacheco, K.A. Allergy to Surgical Implants. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 56, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.D.; Ko, F.C.; Virdi, A.S.; Sumner, D.R.; Ross, R.D. Biomechanics of Implant Fixation in Osteoporotic Bone. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2020, 18, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoen, A.H. Infinite Periodic Minimal Surfaces Without Self-Intersections; NASA Technical Report; NASA: Greenbelt, MD, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Krejčí, T.; Řehounek, L.; Jíra, A.; Šejnoha, M.; Kruis, J.; Koudelka, T. Homogenization of Elastic Properties of Trabecular Structuresfor Modern Implants. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Numerical Analysis and Applied Mathematics 2019 (ICNAAM-2019), Rhodes, Greece, 23–28 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewska, A.; Dean, D. The role of stiffness-matching in avoiding stress shielding-induced bone loss and stress concentration-induced skeletal reconstruction device failure. Acta Biomater. 2024, 173, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liao, W.; Dai, N.; Dong, G.; Tang, Y.; Xie, Y.M. Optimal design and modeling of gyroid-based functionally graded cellular structures for additive manufacturing. Comput.-Aided Des. 2018, 107, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jíra, A.; Šejnoha, M.; Krejčí, T.; Vorel, J.; Řehounek, L.; Marseglia, G. Mechanical Properties of Porous Structures for Dental Implants: Experimental Study and Computational Homogenization. Materials 2021, 14, 4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tshephe, T.S.; Akinwamide, S.O.; Olevsky, E.; Olubambi, P.A. Additive manufacturing of titanium-based alloys- A review of methods, properties, challenges, and prospects. Heliyon 2022, 8, 09041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolde, Z.; Starý, V.; Cvrček, L.; Vandrovcová, M.; Remsa, J.; Daniš, S. Growth of a TiNb adhesion interlayer for bioactive coatings. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 80, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jirka, I.; Vandrovcová, M.; Frank, O.; Tolde, Z.; Plšek, J.; Luxbacher, T.; Bačáková, L.; Starý, V. On the role of Nb-related sites of an oxidized β-TiNb alloy surface in its interaction with osteoblast-like MG-63 cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 1636–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandrovcová, M.; Tolde, Z.; Vaněk, P.; Nehasil, V.; Doubková, M.; Trávníčková, M.; Drahokoupil, J.; Buixaderas, E.; Borodavka, F.; Novakova, J.; et al. Beta-Titanium Alloy Covered by Ferroelectric Coating—Physicochemical Properties and Human Osteoblast-Like Cell Response. Coatings 2021, 11, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlčák, P.; Fojt, J.; Koller, J.; Drahokoupil, J.; Smola, V. Surface pre-treatments of Ti-Nb-Zr-Ta beta titanium alloy: The effect of chemical, electrochemical and ion sputter etching on morphology, residual stress, corrosion stability and the MG-63 cell response. Results Phys. 2021, 28, 104613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Ma, X.; Wang, D.; Zhang, H. Microstructural and Mechanical Properties of β-Type Ti–Nb–Sn Biomedical Alloys with Low Elastic Modulus. Metals 2019, 9, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Microstructure and Properties of Materials; World Scientific: Singapore, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellizzari, M.; Jam, A.; Tschon, M.; Fini, M.; Lora, C.; Benedetti, M. A 3D-Printed Ultra-Low Young’s Modulus β-Ti Alloy for Biomedical Applications. Materials 2020, 13, 2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, H. Wolff’s Law: An ‘MGS’ derivation of Gamma in the Three-Way Rule for mechanically controlled lamellar bone modeling drifts. Bone Miner. 1993, 22, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hybášek, V.; Fojt, J.; Málek, J.; Jablonská, E.; Pruchová, E.; Joska, L.; Ruml, T. Mechanical properties, corrosion behaviour and biocompatibility of TiNbTaSn for dentistry. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolken, H.; Callens, S.; Leeflang, M.; Mirzaali, M.; Zadpoor, A. Merging strut-based and minimal surface meta-biomaterials: Decoupling surface area from mechanical properties. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 52, 102684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Chen, S.; Liang, J.; Liu, C. Effect of atomization pressure on the breakup of TA15 titanium alloy powder prepared by EIGA method for laser 3D printing. Vacuum 2017, 143, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fojt, J.; Kačenka, Z.; Jablonská, E.; Hybášek, V.; Pruchová, E. Influence of the surface etching on the corrosion behaviour of a three-dimensional printed Ti–6Al–4V alloy. Mater. Corros. 2020, 71, 1691–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN ISO 10993; Testing of Medical Devices. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Oliver, W.C.; Pharr, G.M. An improved technique for determining hardness and elastic modulus using load and displacement sensing indentation experiments. J. Mater. Res. 1992, 7, 1564–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.; Huang, S.; Yang, J.; Qi, M.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, D.; Qiu, J.; Lei, J.; Gong, B.; et al. Mechanical properties anisotropy of Ti6Al4V alloy fabricated by beta forging. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2023, 33, 3348–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.Y.; Huang, J.C.; Lin, C.H.; Pan, C.T.; Chen, S.Y.; Yang, T.L.; Lin, D.Y.; Lin, H.K.; Jang, J.S.C. Anisotropic response of Ti-6Al-4V alloy fabricated by 3d printing selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 682, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ti25Nb4Ta8Sn | Ti6Al4V | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without | With | Without | With | ||

| t [μm] | Annealing | Annealing | Etching | Etching | |

| [N] | 408 ± 12 | 208 ± 30 | 1009 ± 43 | 760 ± 85 | |

| 500 | [MPa] | 204 ± 6 | 135 ± 15 | 505 ± 22 | 380 ± 75 |

| E [MPa] | 3620 ± 108 | 3730 ± 410 | 7910 ± 320 | 6780 ± 630 | |

| [N] | 889 ± 38 | 674 ± 86 | 3570 ± 129 | 3571 ± 106 | |

| 750 | [MPa] | 296 ± 13 | 225 ± 29 | 1190 ± 83 | 1190 ± 62 |

| E [MPa] | 3810 ± 152 | 3970 ± 460 | 7930 ± 310 | 7790 ± 234 | |

| [N] | 1443 ± 69 | 1011 ± 101 | 4579 ± 180 | 4959 ± 133 | |

| 1000 | [MPa] | 361 ± 17 | 253 ± 25 | 1145 ± 145 | 1247 ± 46 |

| E [MPa] | 3940 ± 190 | 4184 ± 420 | 7950 ± 390 | 8040 ± 280 | |

| Group I | Group II | Group III | Group IV | ||

| Direction of Nanoindentation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| DI | DII | DIII | |

| [MPa] | 3212 ± 189 | 3376 ± 219 | 2336 ± 188 |

| [GPa] | 52.2 ± 4.8 | 75.9 ± 3.3 | 16.1 ± 0.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jíra, A.; Kruis, J.; Tolde, Z.; Krčil, J.; Jírů, J.; Fojt, J. Effect of Sample Thickness and Post-Processing on Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Titanium Alloy. Materials 2025, 18, 5008. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18215008

Jíra A, Kruis J, Tolde Z, Krčil J, Jírů J, Fojt J. Effect of Sample Thickness and Post-Processing on Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Titanium Alloy. Materials. 2025; 18(21):5008. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18215008

Chicago/Turabian StyleJíra, Aleš, Jaroslav Kruis, Zdeněk Tolde, Jan Krčil, Jitřenka Jírů, and Jaroslav Fojt. 2025. "Effect of Sample Thickness and Post-Processing on Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Titanium Alloy" Materials 18, no. 21: 5008. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18215008

APA StyleJíra, A., Kruis, J., Tolde, Z., Krčil, J., Jírů, J., & Fojt, J. (2025). Effect of Sample Thickness and Post-Processing on Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Titanium Alloy. Materials, 18(21), 5008. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18215008