Enhancing the Chloride Adsorption and Durability of Sulfate-Resistant Cement-Based Materials by Controlling the Calcination Temperature of CaFeAl-LDO

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

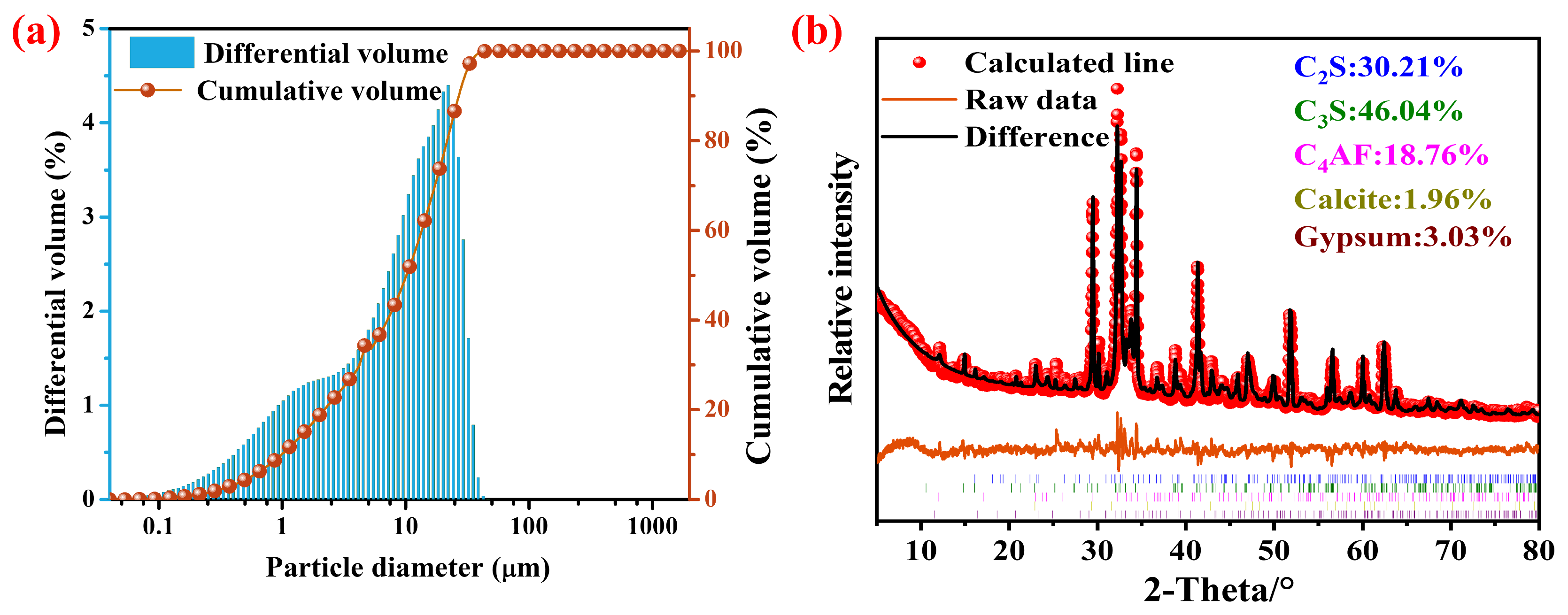

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Calcined LDO-CFA

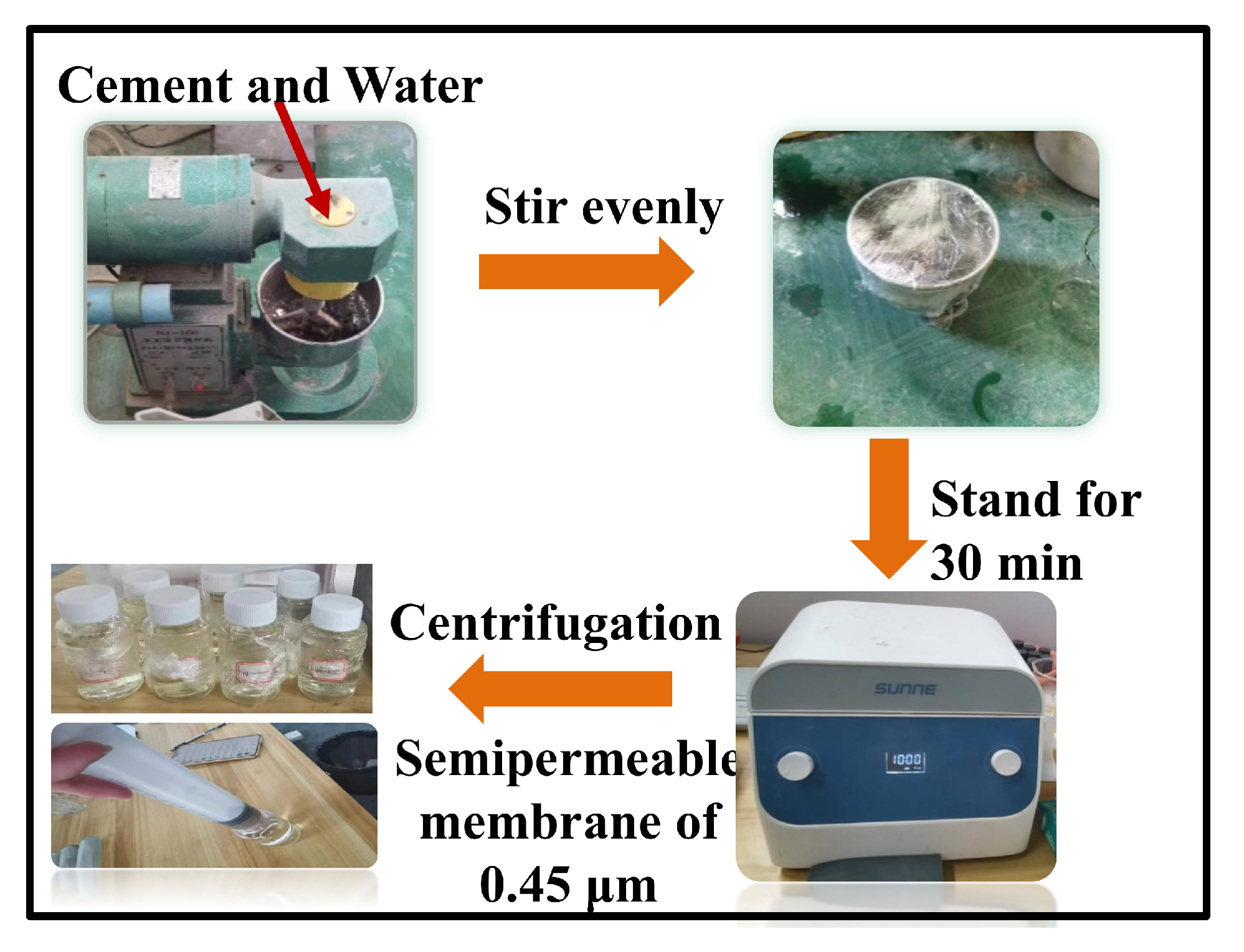

2.3. Extraction Process of Concrete Pore Solutions

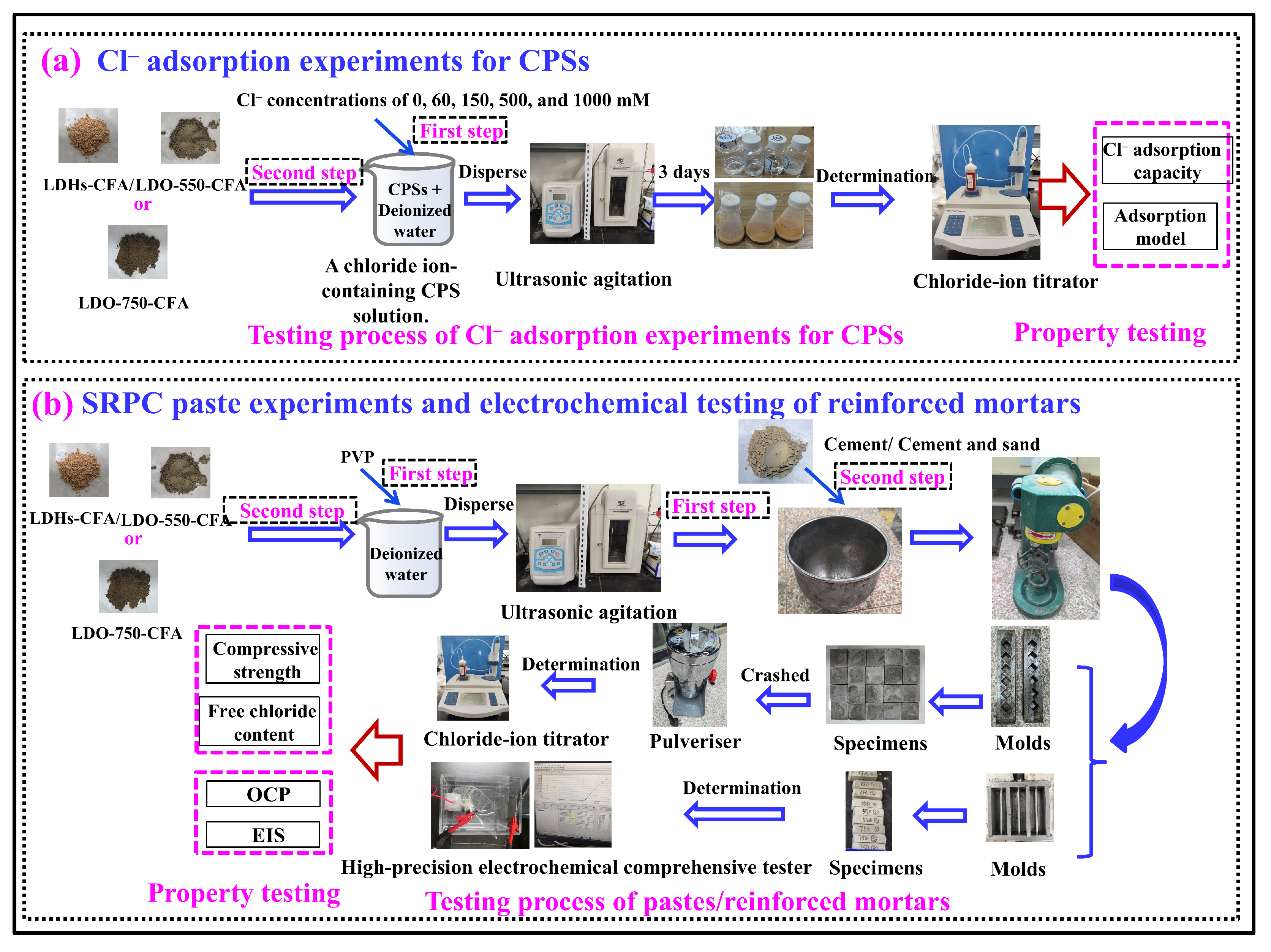

2.4. Preparation of Specimens

2.5. Test Method

2.5.1. Chloride Ion Adsorption Determination

2.5.2. Compressive Strength Test

2.5.3. Electrochemical Tests

2.6. Observation of Microstructure

3. Results and Discussion

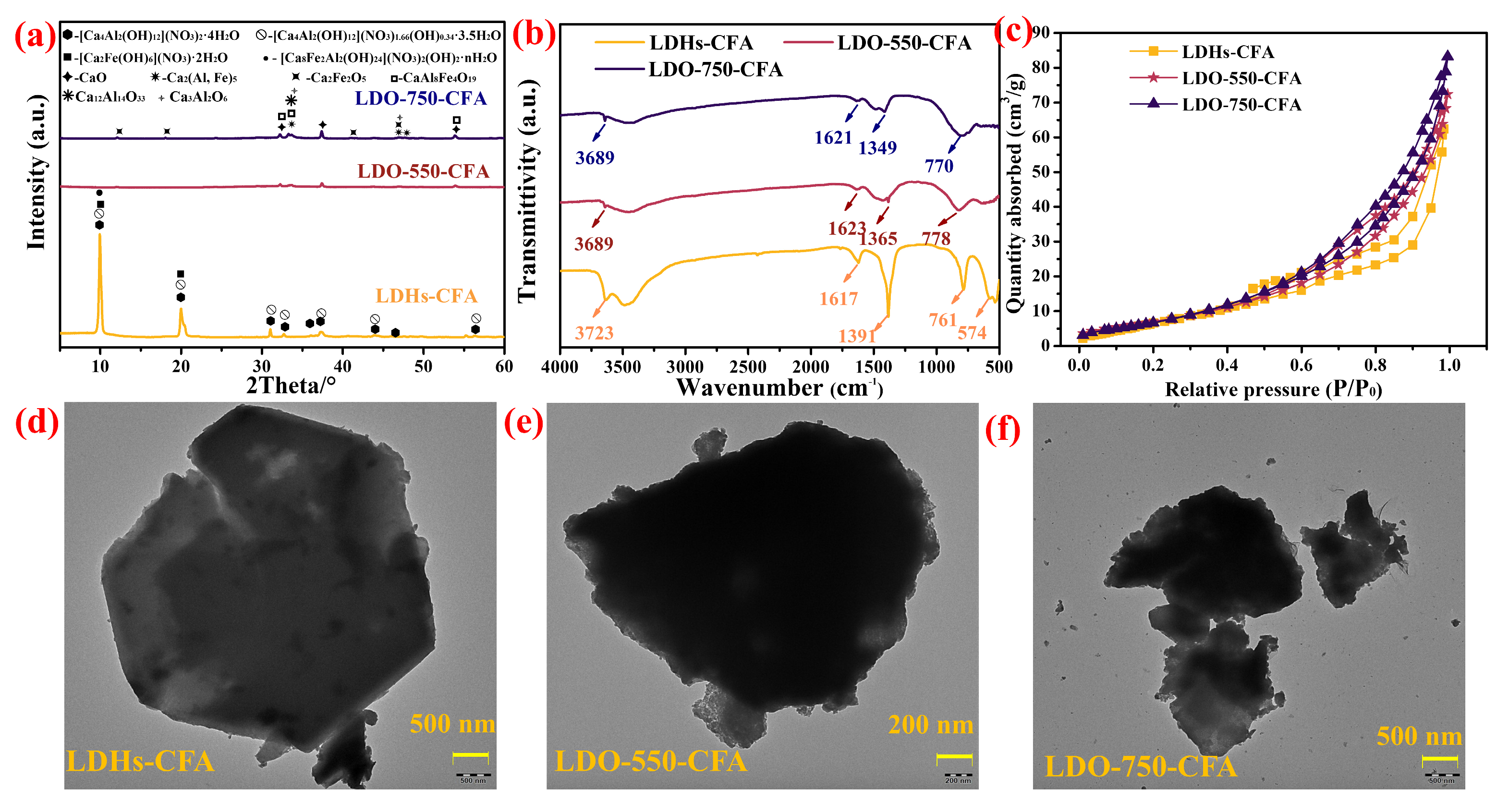

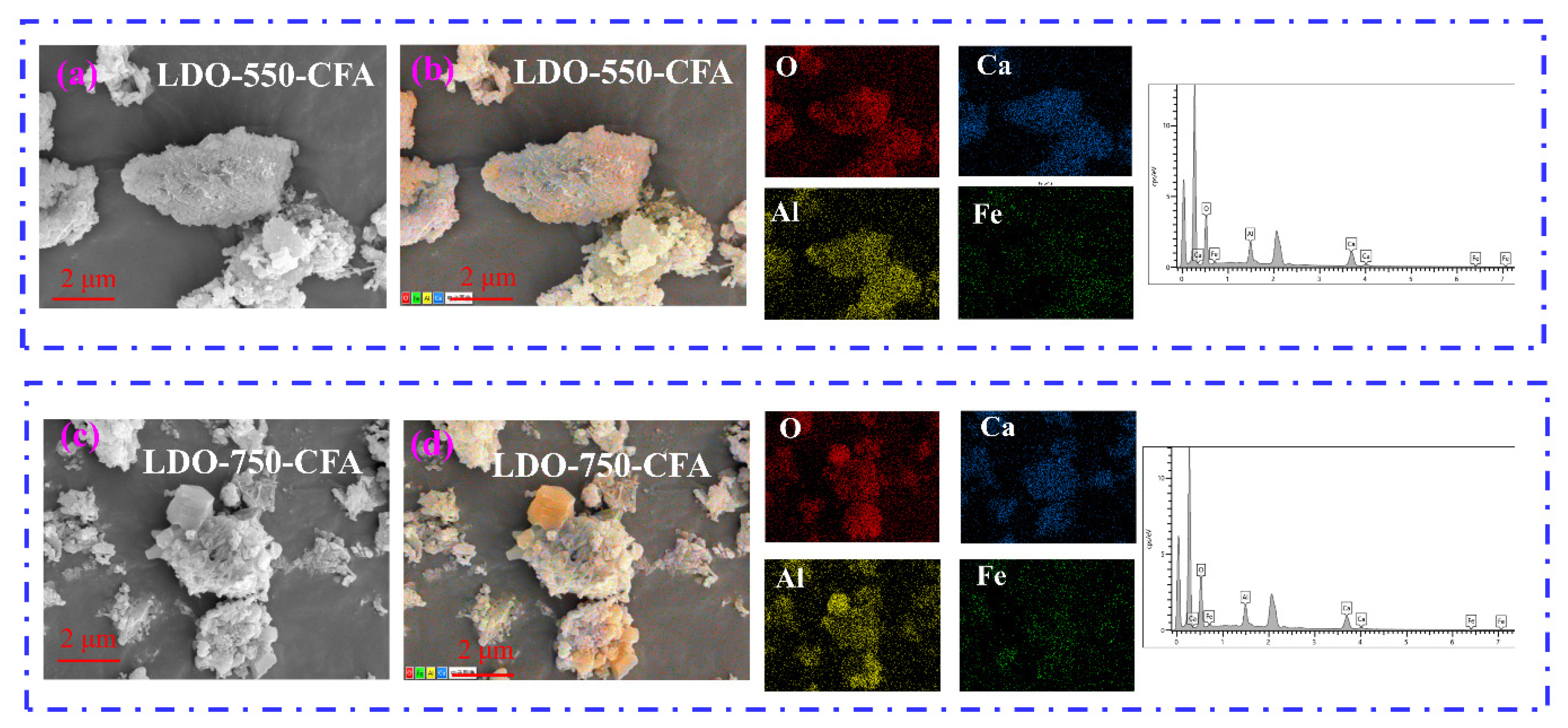

3.1. Characterization of the Calcined LDO-CFA

3.2. Cl− Adsorption Properties of Calcined LDO-CFA in CPSs

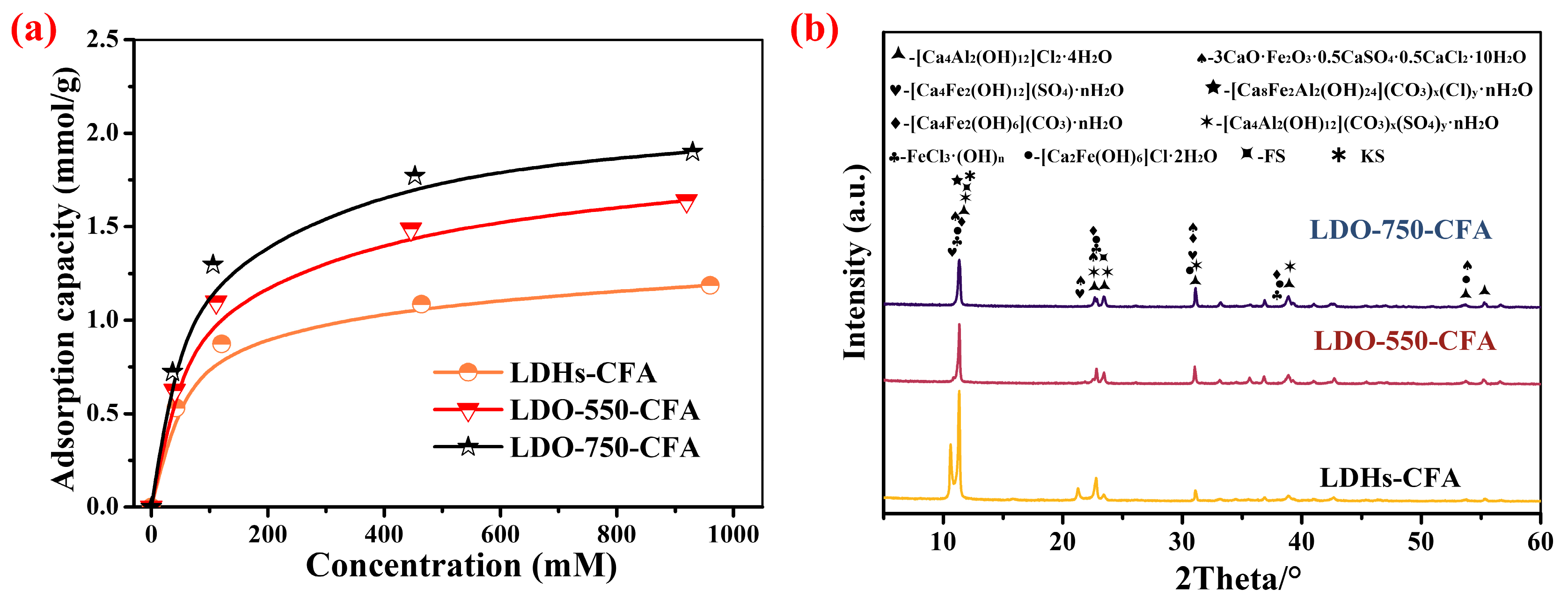

3.2.1. Effect of Concentration on Ion Exchange Capacity

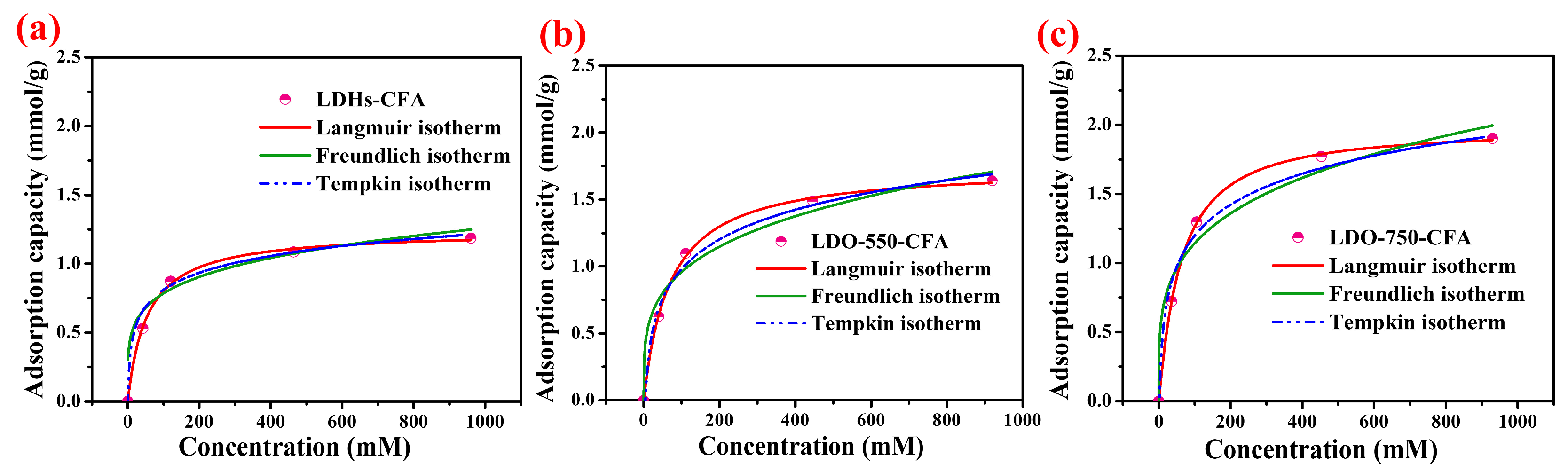

3.2.2. Adsorption Isotherm Analysis

3.3. Properties of Calcined LDO-CFA in Chloride-Containing Hardened SPRC Pastes

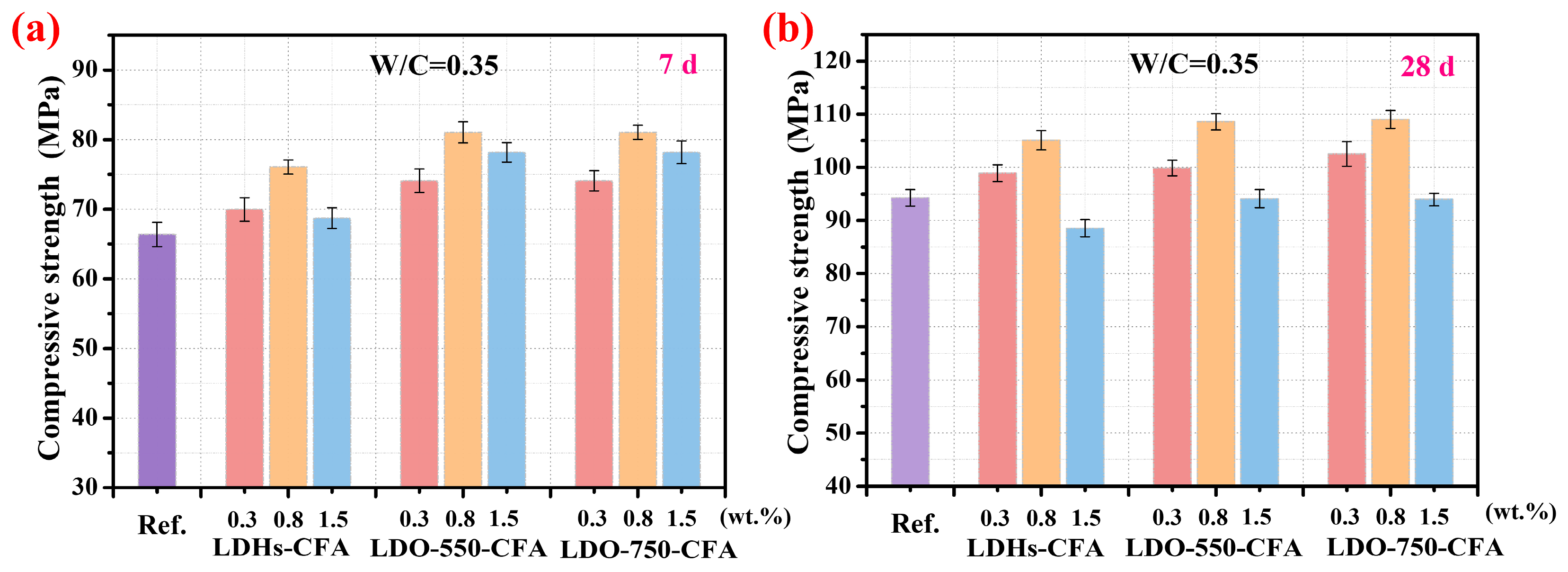

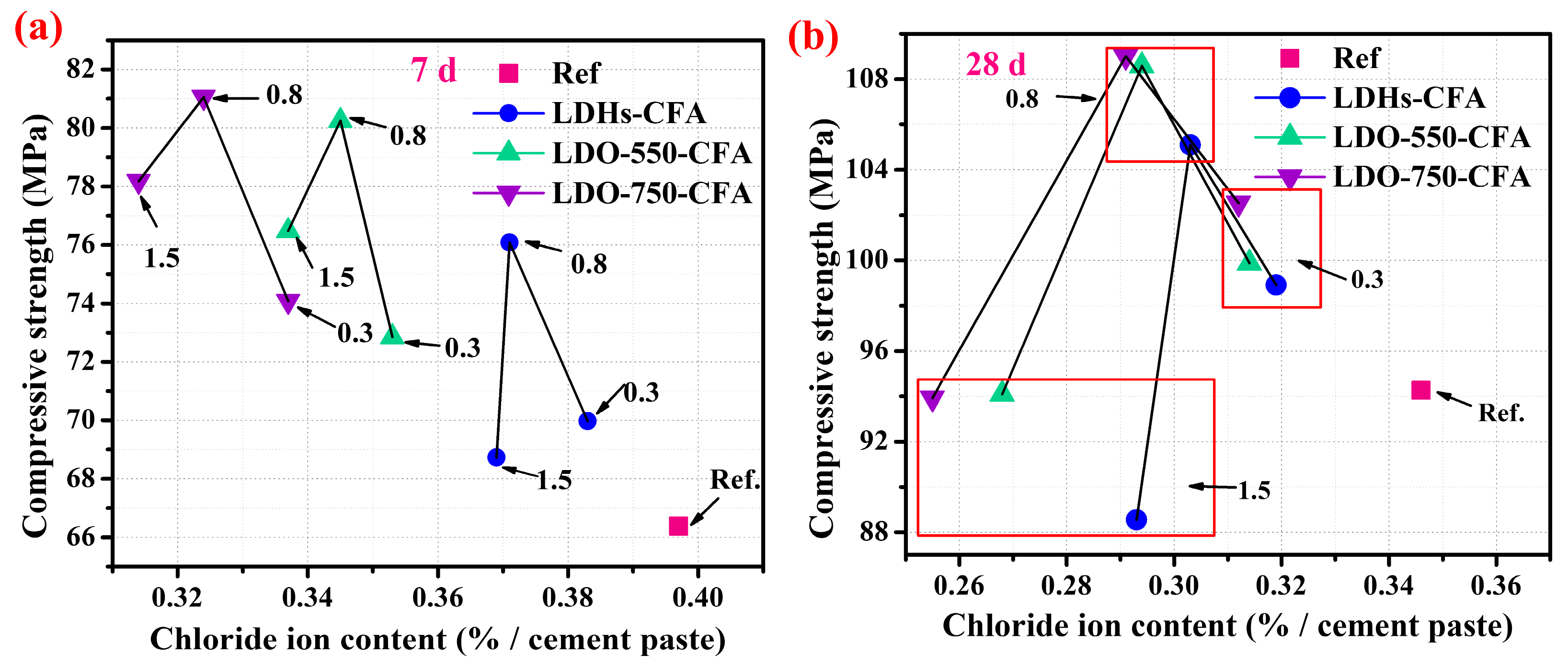

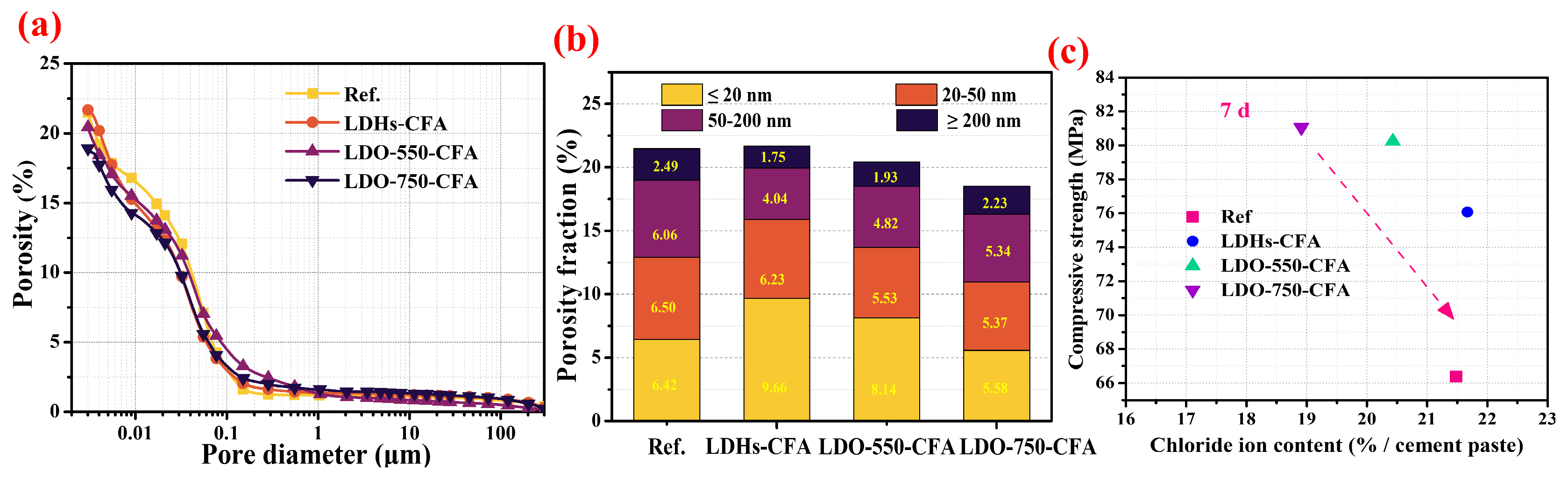

3.3.1. Mechanical Properties

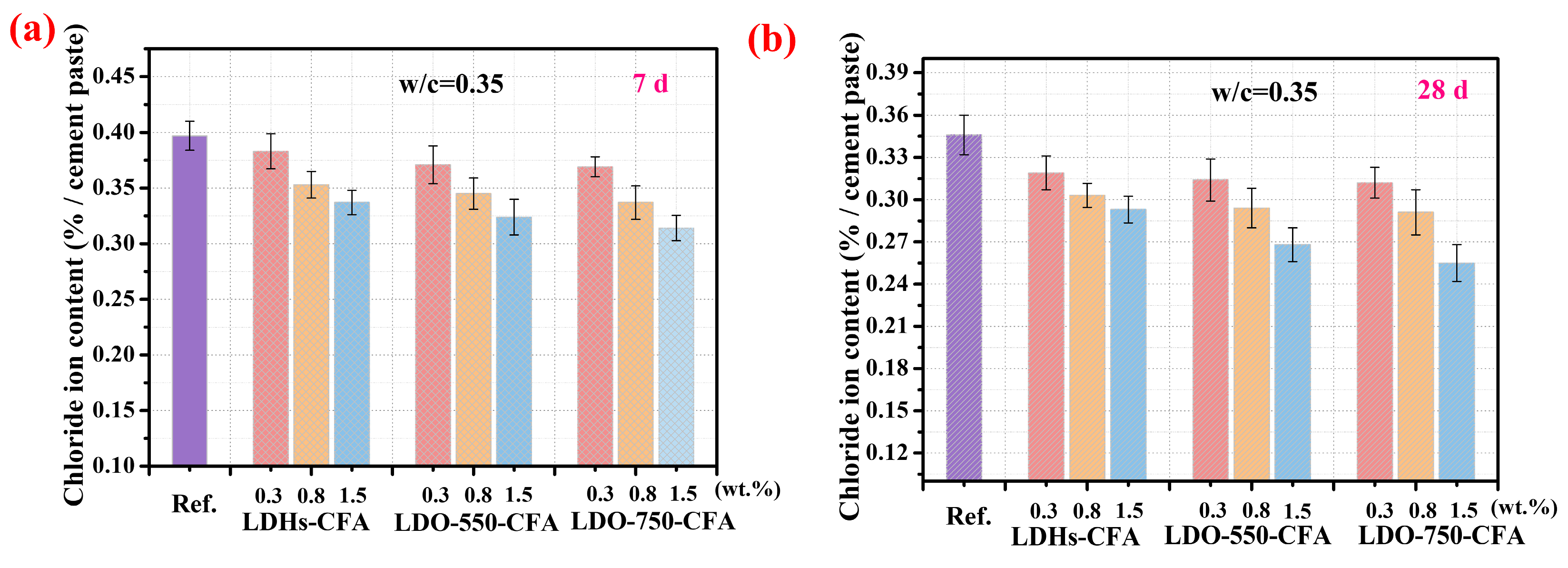

3.3.2. Chloride Ion Adsorption Properties

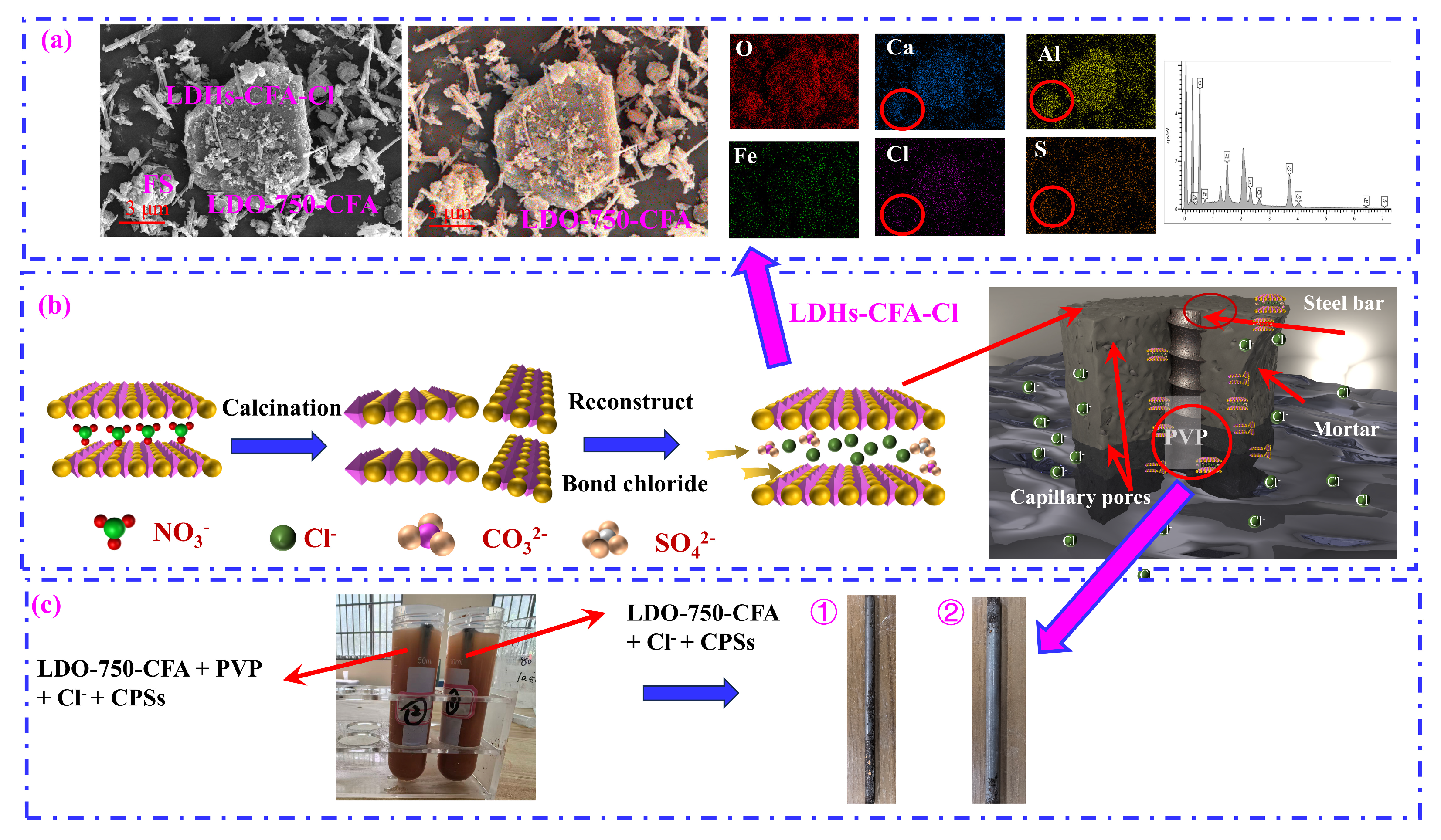

3.4. Microstructure of Chloride-Containing LDO-CFA Cement Paste

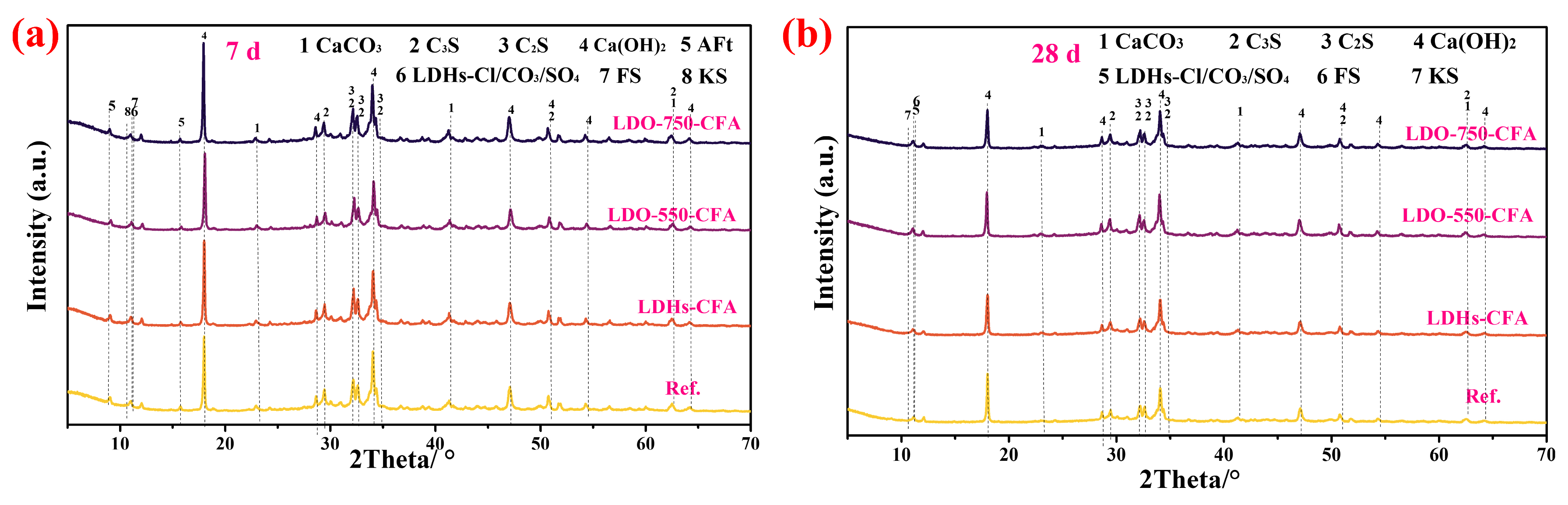

3.4.1. XRD

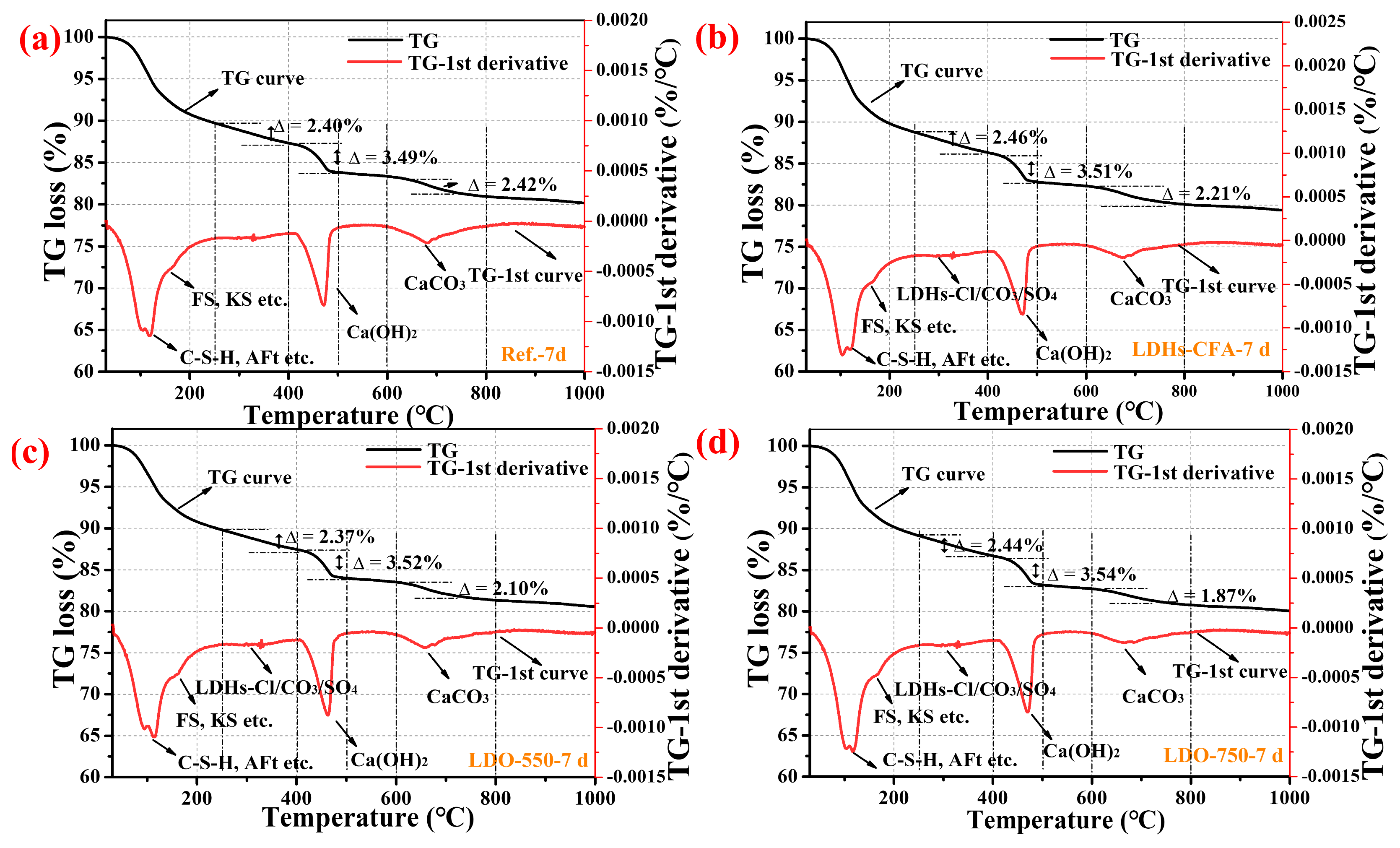

3.4.2. TG-DTG

3.4.3. Pore Structure

3.5. Corrosion Inhibition of LDO-CFA in Reinforced Mortars

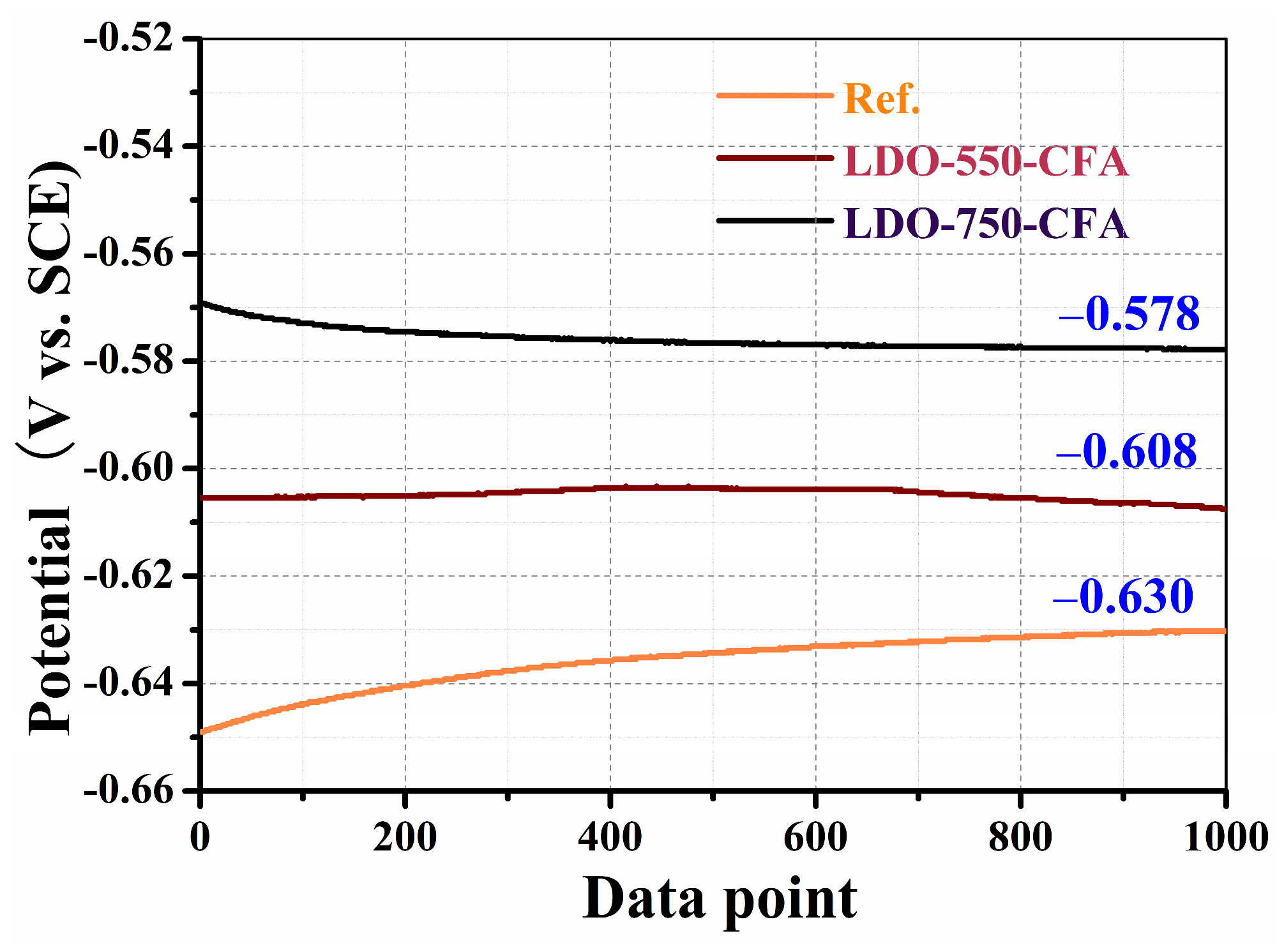

3.5.1. Open Circuit Potential

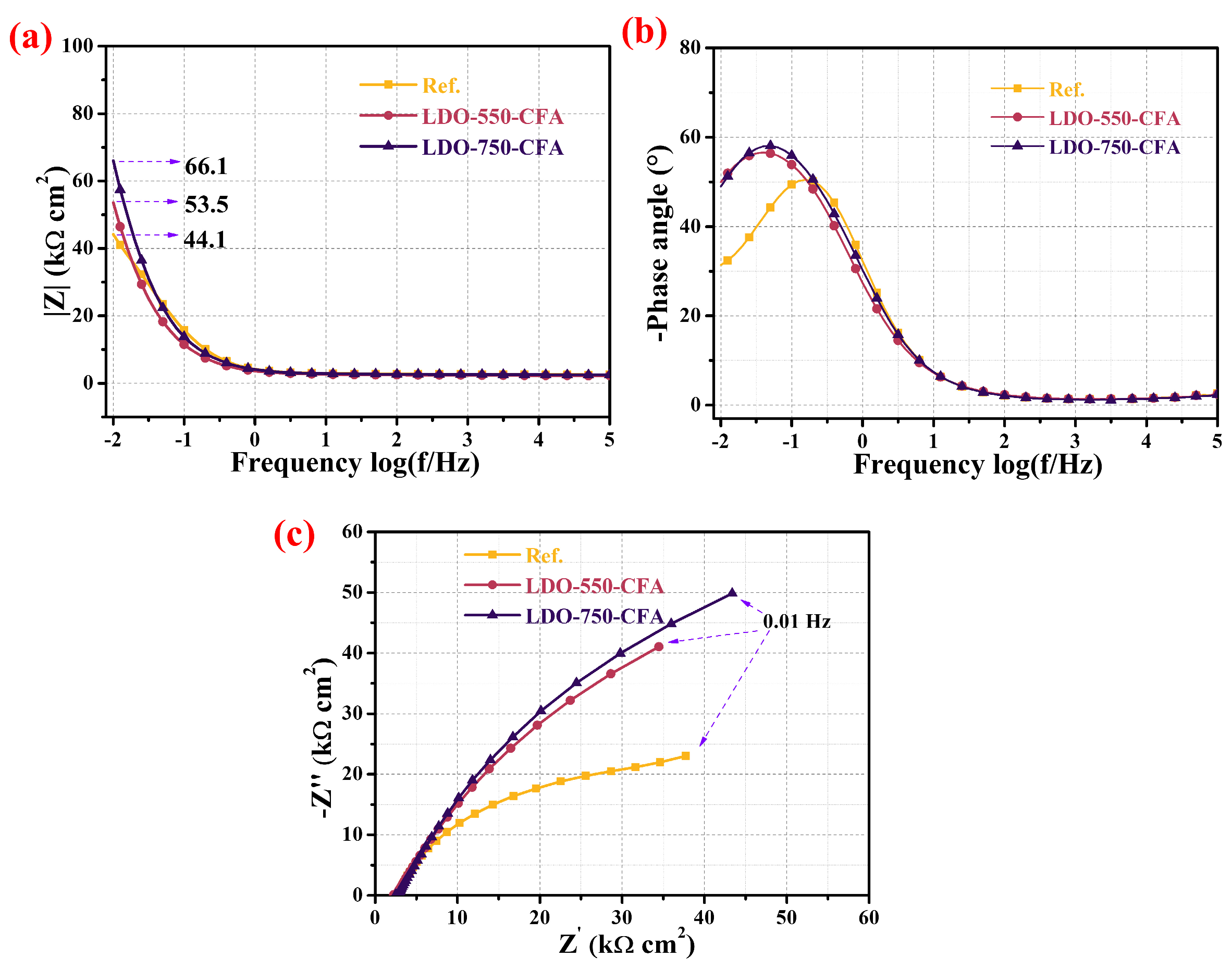

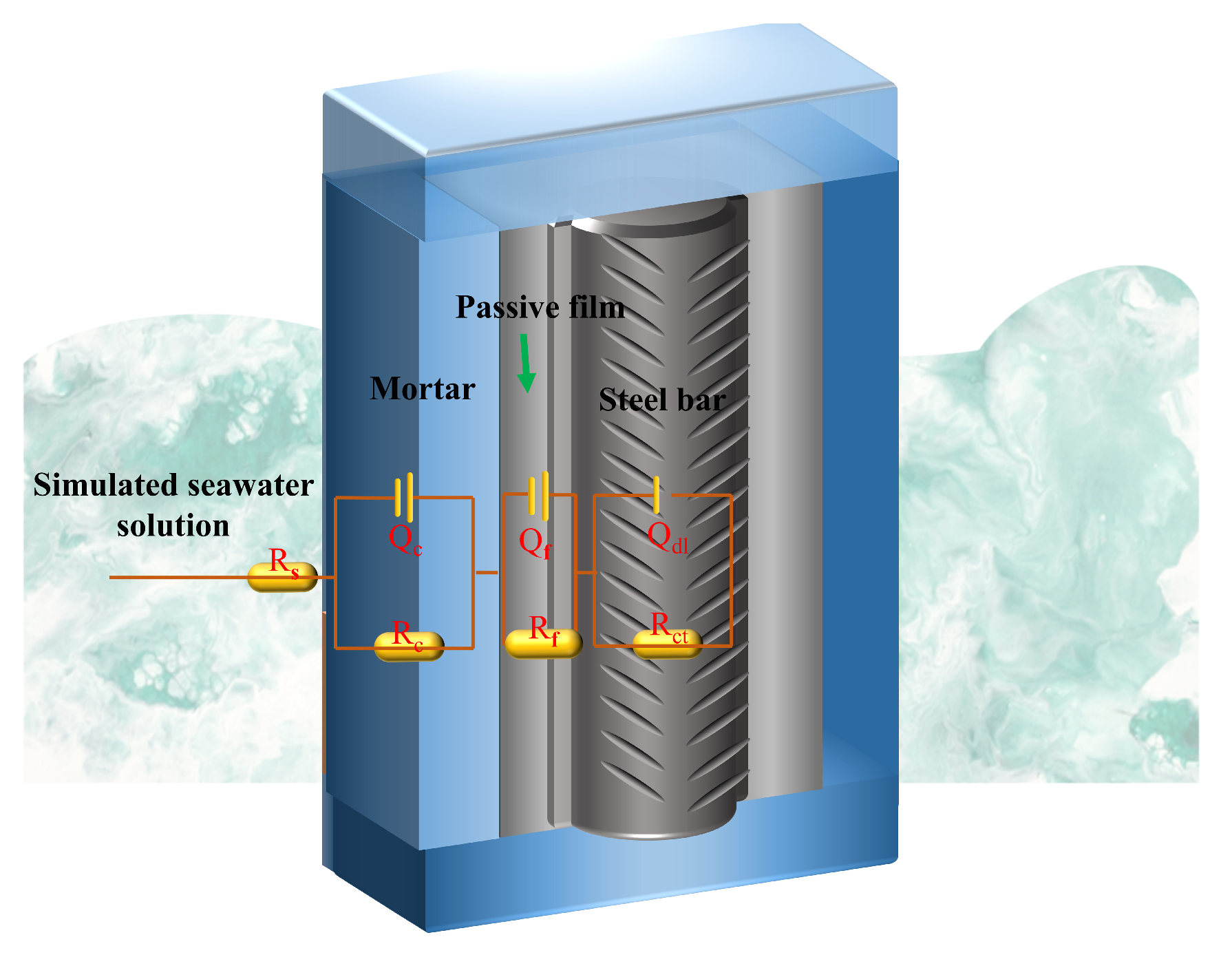

3.5.2. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Measurement

3.6. Discussion

3.7. Practical Implications and Limitations

4. Conclusions

- The chemical composition and microstructure of LDO-CFA calcined at 550 and 750 °C were characterized by XRD, FTIR, BET, SEM mapping, and TEM. Calcination of the LDO-CFA system generates several crystalline phases, namely CaO, CaAl8Fe4O19, Ca2(Al, Fe)O5, Ca2Fe2O5, Ca12Al14O33, and Ca3Al2O6.

- LDO-CFA shows a high Cl− adsorption capacity in both CPSs and cement-based materials. The process follows the Langmuir model, suggesting uniform monolayer adsorption. LDO-750-CFA showed a peak capacity of 1.98 mmol/g in CPSs, surpassing LDHs-CFA by 60.1%. The long-term efficacy was confirmed in SRPC pastes, where free Cl− was lowered to 0.255–0.293% after 28 days of curing.

- At an optimal dosage of 0.8 wt.%, the LDO-750-CFA paste significantly improved the compressive strength of the SPRC paste, increasing it by 22.1% at 7 days and 15.6% at 28 days compared to the control. At 0.8 wt.%, the 28-day paste achieves an optimal balance, exhibiting 16.1% Cl− adsorption efficiency while retaining a compressive strength exceeding 109 MPa.

- Electrochemical tests revealed that, compared to the control, the LDO-750-CFA specimen improved the corrosion resistance of reinforced mortar by increasing the OCP, impedance arc radii, |Z|0.01 values, Rp, Rf, Rct, and inhibition efficiency, while reducing the Cf and Cdl. It also delayed the initiation of steel corrosion.

- This improvement originates from synergistic mechanisms within the mortar: LDO-750-CFA refines the pore structure and adsorbs Cl−, while the Fe3+ from it rapidly forms a protective passivation film. This effect is further boosted by PVP, which ensures the uniform dispersion of LDO-750-CFA and concurrently contributes an organic passive film.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| SRPC | Sulphate-resistant Portland cement |

| LDHs | Layered double hydroxides |

| LDO | Layered double oxide |

| LDHs-CFA | CaFeAl-NO3-layered double hydroxides |

| LDO-CFA | CaFeAl-layered double oxide |

| CPSs | Concrete pore solutions |

| C4AF | Tetracalcium aluminoferrite |

| SCE | Saturated calomel reference electrode |

| EIS | Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy |

| FS | Friedel’s salt |

| KS | Kuzel’s salt |

| OCP | Open circuit potential |

| PVP | Polyvinylpyrrolidone |

| C3S | Tricalcium silicate |

| C3A | Ttricalcium aluminate |

| AFt | Ettringite |

References

- Trivedi, S.S.; Snehal, K.; Das, B.B.; Barbhuiya, S. A comprehensive review towards sustainable approaches on the processing and treatment of construction and demolition waste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 393, 132125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xing, Q.; Bao, J.; Xue, S. Silicone lubricant infused polydimethylsiloxane-based coating with enhanced stability for improving the durability of marine concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 482, 141707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, J.; Bazli, M.; Dhungana, S.; Rajabipour, A.; Hassanli, R.; Arashpour, M. Sand-coated hybrid FRP tubes for marine applications: Bond performance with seawater-sea sand concrete under seawater. Mar. Struct. 2025, 104, 103872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Y. A space fractal derivative crack model for characterizing chloride ions super diffusion in concrete in the marine tidal zone. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 450, 138585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Gu, H.; Geng, Y.; Wang, P.; Gao, S.; Li, S. Hydrothermal synthesis of CaAl-LDH intercalating with eugenol and its corrosion protection performances for reinforcing bar. Materials 2023, 16, 2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, C.; Jia, C.; Li, D. A comparative study on chloride diffusion in concrete exposed to different marine environment conditions. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 94, 109845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.J.; Zhong, A.N.; Zheng, S.Y.; Guo, H.R.; He, C. Highly enhancing chloride immobilization of cement pastes by novel polymer dots. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 442, 137523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Shi, Z.; Hu, X.; Khaskhoussi, A.; Shi, C. Chloride binding of cement paste containing wet carbonated recycled concrete fines. Cem. Concr. Res. 2025, 191, 107823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Xiao, H.; Guan, S. Influence of Nano-SiO2 and Nano-TiO2 on properties and microstructure of cement-based materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 459, 139805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, A.A.; Anaee, R.; Nasr, M.S.; Shubbar, A.; Alahmari, T.S. Mechanical properties, corrosion resistance and microstructural analysis of recycled aggregate concrete made with ceramic wall waste and ultrafine ceria. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shui, Z.; Gao, X.; Huang, Y.; Yu, R.; Xiao, X. Modification on the chloride binding capacity of cementitious materials by aluminum compound addition. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 222, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Deng, J.; Cui, H.; Sun, G. Highly efficient resistance to chloride ion penetration and enhanced compressive strength in cement coupled with cationic polymer grafted nano-silica. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 478, 141420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Gao, H.; Xu, R.; Guo, Z. Mg-Al layered double hydroxides derived from secondary aluminum ash for soil remediation contaminated with Cd (II) and Cr (VI). J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 497, 139585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Sainio, J.; Shi, J.; Jiang, H.; Ali, B.; Han, N.; Kallio, T. Bifunctional surface-distributed RuO2 on NiFe double layer hydroxide for efficient alkaline water splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 520, 165999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Jiang, G.; Zhang, M.; Dai, Y.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, N.; Cao, Y. Sustainable chloride ion removal from wastewater via capacitive deionization: Anion-preintercalated and Ti-modulated layered double hydroxides for high-efficiency adsorption. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 165393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Yang, J.; Niu, M.; Hanif, A.; Li, G. Synthesis of CaLiAl-LDHs and its optimization on the properties and chloride binding capacity of eco-friendly marine cement-based repair materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 443, 141183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Ma, Y.; Yu, Q. Insight into ion exchange behavior of LDHs: Asynchronous chloride adsorption and intercalated ions release processes. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 147, 105433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Tian, D.; Dong, M.; Lv, M.; Yang, X.; Lu, S. Effects of interlayer-modified layered double hydroxides with organic corrosion inhibiting ions on the properties of cement-based materials and reinforcement corrosion in chloride environment. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 154, 105793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, X.; Chen, T.; Sun, M.; Ou, Y.; Ji, X. A novel strategy to improve the early age strength of high-volume fly ash cement pastes: The combination of seawater and calcined layered double hydroxides as an innovative chemical activator. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 473, 141038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Ji, Y.; Liu, A.; Zhang, H.; Qin, Z.; Long, W. The adsorption and diffusion behavior of chloride in recycled aggregate concrete incorporated with calcined LDHs. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 148, 105452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, A.A.L.; Nobre, T.R.S.; Teobaldo, G.B.M.; de Oliveira, C.L.P.; Coelho, A.C.V.; Angulo, S.C. Ca-Al layered double hydroxides (LDHs) from the rehydration of calcined katoite: Chloride binding capacity and cementitious properties. Appl. Clay Sci. 2025, 276, 107947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Pan, C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhu, Y. Chloride binding in cement paste with calcined Mg-Al-CO3 LDH (CLDH) under different conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 273, 121678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y. In situ engineered layered ZIF-8@ZnAl-LDO hybrids for high-capacity chloride adsorption and synergistic corrosion protection. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 728, 138520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douba, A.; Hou, P.; Kawashima, S. Hydration and mechanical properties of high content nano-coated cements with nano-silica, clay and calcium carbonate. Cem. Concr. Res. 2023, 168, 107132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, W.; Wu, N.; Sun, L.; Shen, P.; Wang, X.; Li, Y. Highly-dispersed carboxymethyl cellulose and polyvinylpyrrolidone functionalized boron nitride for enhanced thermal conductivity and hydrophilicity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 617, 156485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.A.; Castel, A.; Khan, M.S.; Mahmood, A.H. Durability of calcium aluminate and sulphate resistant Portland cement based mortars in aggressive sewer environment and sulphuric acid. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 124, 105852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Gong, C.; Wang, Y.; Huo, L.; Lu, L. Effect of nano-silica on structure and properties of high sulfate resistant Portland cement mixed with mineral powder or fly ash. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 66, 105843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 748-2023; Sulfate Resistance Portland Cement. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2023.

- Yang, L.; Chen, M.; Lu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Wang, J.; Lu, L.; Cheng, X. Synthesis of CaFeAl layered double hydroxides 2D nanosheets and the adsorption behaviour of chloride in simulated marine concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 114, 103817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D512-12; Standard Test Methods for Chloride Ion in Water. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012.

- Yazdi, M.A.; Gruyaert, E.; Van Tittelboom, K.; De Belie, N. New findings on the contribution of Mg-Al-NO3 layered double hydroxides to the hydration and chloride binding capacity of cement pastes. Cem. Concr. Res. 2023, 163, 107037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, Q.; Zheng, H.; Yu, L.; Jiang, L.; Gu, Z.; Li, W. Understanding strengthening mechanisms of Ca-LDO on cementitious materials. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 145, 105340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.A.; Picarra, S.; Pinto, A.F.; Pereira, M.F.; Rucha, M.; Montemor, M.F.; da Fonseca, B.S. Layer double hydroxide (LDH): Synthesis and incorporation in alkoxysilanes for stone conservation. Appl. Clay Sci. 2025, 266, 107687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Kang, H.; Ma, S.; Bai, Y.; Yang, X. High adsorption selectivity of ZnAl layered double hydroxides and the calcined materials toward phosphate. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010, 343, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Niu, D. Performance analysis of calcined Mg-Al layered double hydroxides (CLDH) and its effect on the durability of concrete under the combined action of temperature and sulfate attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 484, 141656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lin, B.; Yu, X.; Li, S.T. Influence of MgAl-LDHs/TiO2 composites on the mechanical and photocatalytic properties of cement pastes and recycled aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 377, 131122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Sun, T.; Wang, X.; He, H.; Shuang, E. Development of high-dispersion CLDH/carbon dot composites to boost chloride binding of cement. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 152, 105669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justnes, H.; Skocek, J.; Østnor, T.A.; Engelsen, C.J.; Skjølsvold, O. Microstructural changes of hydrated cement blended with fly ash upon carbonation. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 137, 106192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C876-91; Standard Specification for Open Circuit Potential in Concrete. American Society for Testing and Materials: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1998.

- Bai, Z.; Meng, S.; Cui, Y.; Sun, Y.; Pei, L.; Hu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, H. A stable anticorrosion coating with multifunctional linkage against seawater corrosion. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 259, 110733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Liu, W.; Chen, L.; Zhang, T.; Fan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, W.; Sun, Y. Unraveling the effect of chloride ion on the corrosion product film of Cr-Ni containing steel in tropical marine atmospheric environment. Corros. Sci. 2022, 209, 110741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wei, J.; Ma, G.; Tan, Q. Effect of MgAl-NO2 LDHs inhibitor on steel corrosion in chloride-free and contaminated simulated carbonated concrete pore solutions. Corros. Sci. 2020, 176, 108940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, J.; Zhou, X.; Zuo, H.; Jiang, L.; Zou, Y.; Shi, J. Effects of stray current and silicate ions on electrochemical behavior of a high-strength prestressing steel in simulated concrete pore solutions. Corros. Sci. 2022, 197, 110083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements | CaO | SiO2 | Fe2O3 | Al2O3 | MgO | SO3 | TiO2 | K2O | Na2O | Others | LOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (wt%) | 58.93 | 18.88 | 4.41 | 4.00 | 3.99 | 3.40 | 0.62 | 0.51 | 0.24 | 1.97 | 3.05 |

| Components | Ca2+ | Na+ | K+ | CO32− | SO42− | OH− |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (mmol/L) | 22.6 | 9.65 | 38.3 | 1.1 | 3.2 | 57.6 |

| Runs | SRPC | Sand | Water | LDO-CFA | PVP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref. | 500 | 1000 | 200 | 0 | 0.1 |

| LDO-550-CFA | 500 | 1000 | 200 | 4.0 | 0.1 |

| LDO-750-CFA | 500 | 1000 | 200 | 4.0 | 0.1 |

| LDO-CFA | Cl−-Adsorbed LDO-CFA | Cement Paste with LDO-CFA |

|---|---|---|

| CaO | [Ca4Al2(OH)12] Cl2·4H2O | CaCO3 |

| CaAl8Fe4O19 | [Ca4Fe2(OH)12] (SO4)n·nH2O | C3S |

| Ca2(Al, Fe)O5 | [Ca4Fe2(OH)12] (CO3)n·nH2O | C2S |

| Ca2Fe2O5 | [Ca4Al2(OH)12] (CO3)x·(SO4)y·nH2O | Ca(OH)2 |

| Ca12Al14O33 | [Ca8Fe2Al2(OH)24] (CO3)x·Cly·nH2O | 3CaO·Al2O3·3CaSO4·32H2O (AFt) |

| Ca3Al2O6 | CaO·Fe2O3·0.5CaSO4·0.5CaCl2·10H2O | LDHs-CFA-Cl/CO3/SO4 |

| CaO·Al2O3·CaCl2·10H2O (FS) | FS | |

| CaO·Al2O3·0.5CaCl2·0.5 CaSO4·10H2O (KS) | KS | |

| FeCl3·(OH)m |

| Adsorption Kinetics Models | LDHs-CFA | LDO-550-CFA | LDO-750-CFA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir isotherm model | |||

| b | 0.018 | 0.013 | 0.011 |

| Qs (mmol/g) | 1.24 | 1.75 | 1.98 |

| R2 | 0.995 | 0.998 | 0.999 |

| Freundlich isotherm model | |||

| KF | 4.877 | 3.849 | 4.000 |

| n | 0.305 | 0.290 | 0.361 |

| R2 | 0.885 | 0.978 | 0.973 |

| Tempkin isotherm model | |||

| b (kJ/mol) | 6.295 | 11.320 | 11.487 |

| KT | 0.971 | 0.217 | 0.405 |

| R2 | 0.975 | 0.992 | 0.967 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, L.; Zhao, X.; Cai, S.; Hua, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Wu, J.; Pang, L.; Gui, X. Enhancing the Chloride Adsorption and Durability of Sulfate-Resistant Cement-Based Materials by Controlling the Calcination Temperature of CaFeAl-LDO. Materials 2025, 18, 4884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214884

Yang L, Zhao X, Cai S, Hua M, Liu J, Liu H, Wu J, Pang L, Gui X. Enhancing the Chloride Adsorption and Durability of Sulfate-Resistant Cement-Based Materials by Controlling the Calcination Temperature of CaFeAl-LDO. Materials. 2025; 18(21):4884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214884

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Lei, Xin Zhao, Shaonan Cai, Minqi Hua, Jijiang Liu, Hui Liu, Junyi Wu, Liming Pang, and Xinyu Gui. 2025. "Enhancing the Chloride Adsorption and Durability of Sulfate-Resistant Cement-Based Materials by Controlling the Calcination Temperature of CaFeAl-LDO" Materials 18, no. 21: 4884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214884

APA StyleYang, L., Zhao, X., Cai, S., Hua, M., Liu, J., Liu, H., Wu, J., Pang, L., & Gui, X. (2025). Enhancing the Chloride Adsorption and Durability of Sulfate-Resistant Cement-Based Materials by Controlling the Calcination Temperature of CaFeAl-LDO. Materials, 18(21), 4884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214884