Pyrolized Diatomaceous Biomass Doped with Epitaxially Growing Hybrid Ag/TiO2 Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterisation and Antibacterial Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Metabolically Doping Diatomaceous Biomass with Titanium

2.2. Preparation of AgNPs/TiO2/Pyrolized Diatomaceous Biomass Composites

2.3. Characterization Methods and Instrumentation

2.4. Antimicrobial Potential Investigation of the Obtained Formulations

3. Results and Discussion

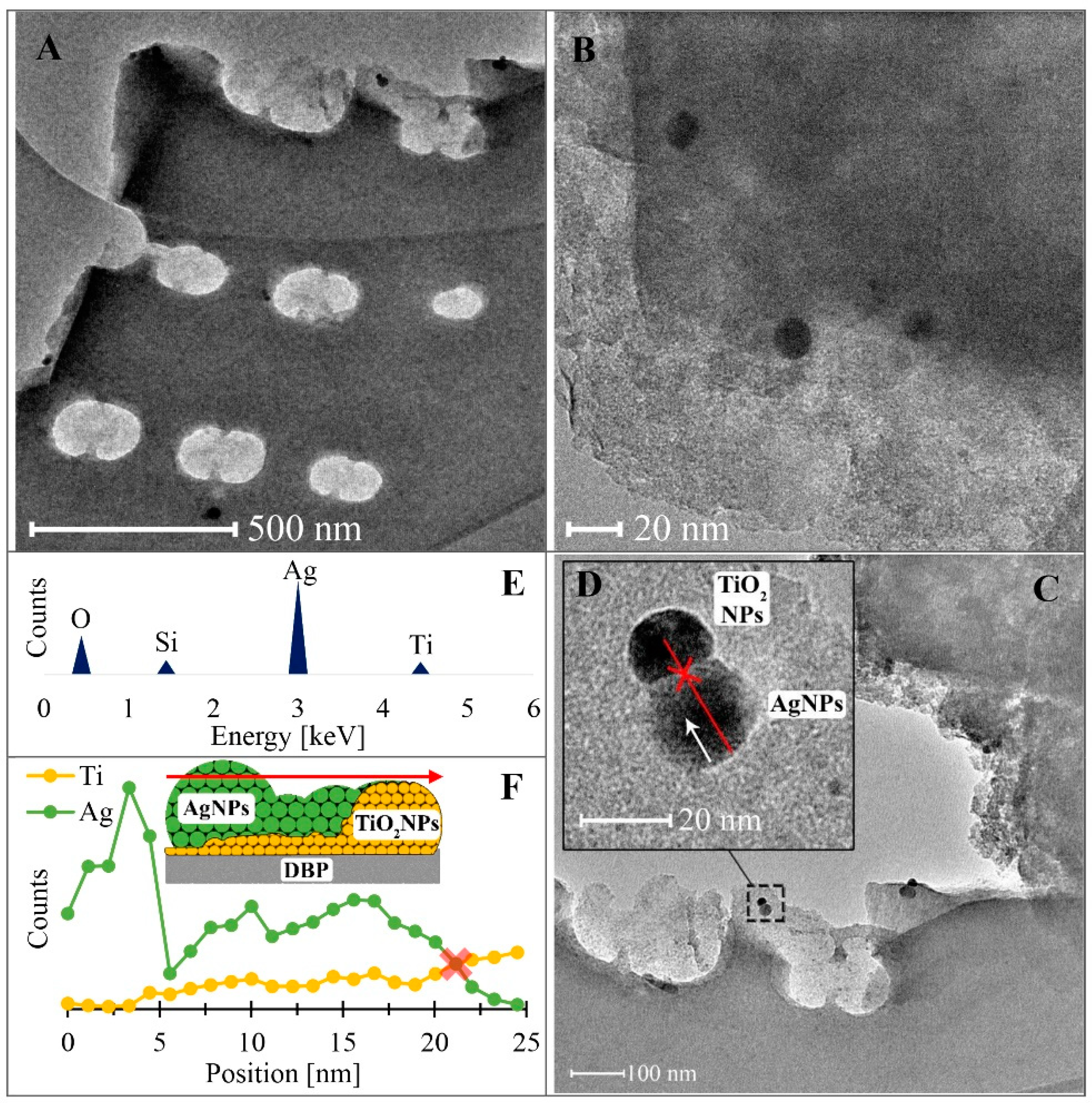

3.1. Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) Studies

3.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy Studies

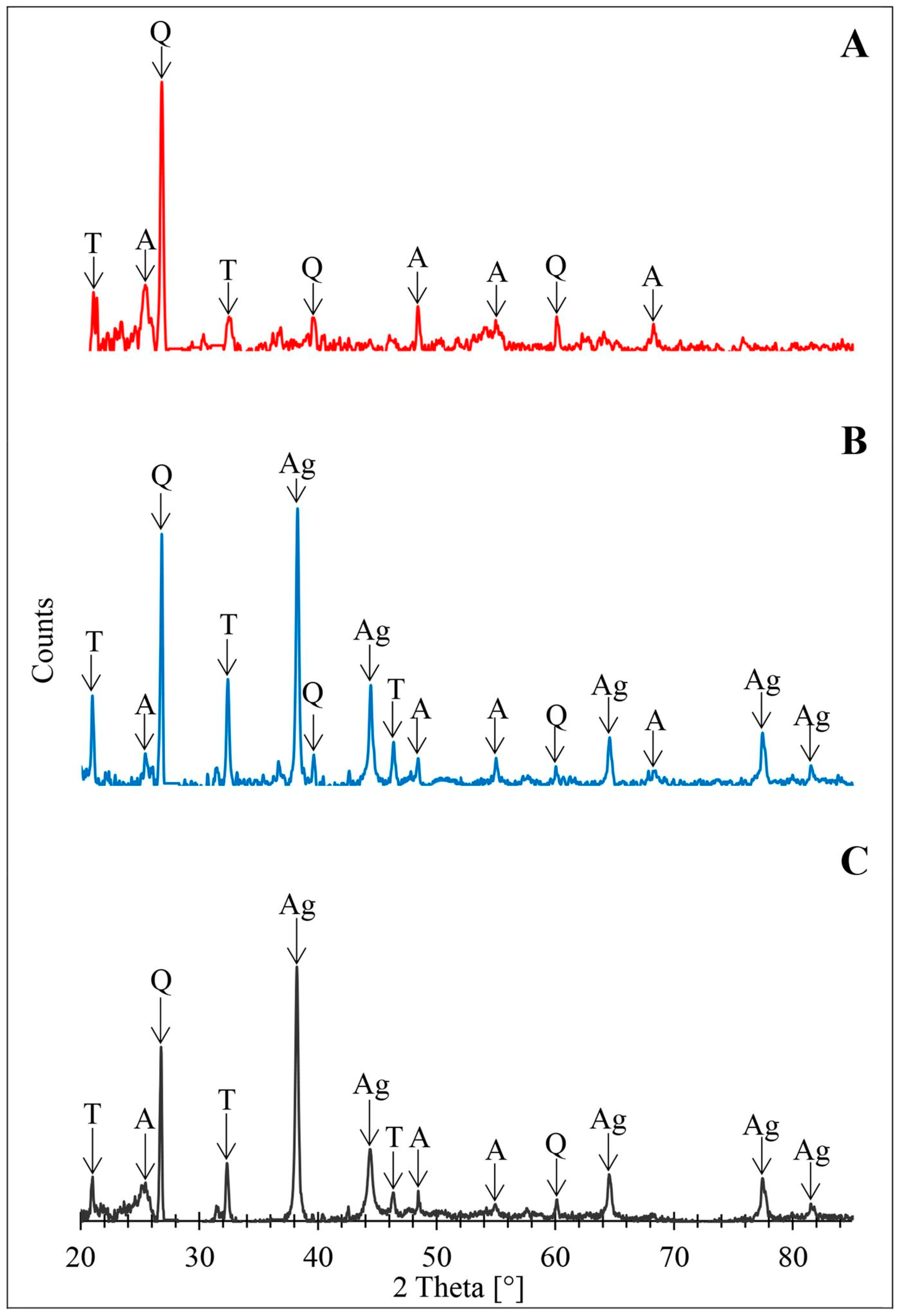

3.3. Powder X-ray Diffraction Analysis

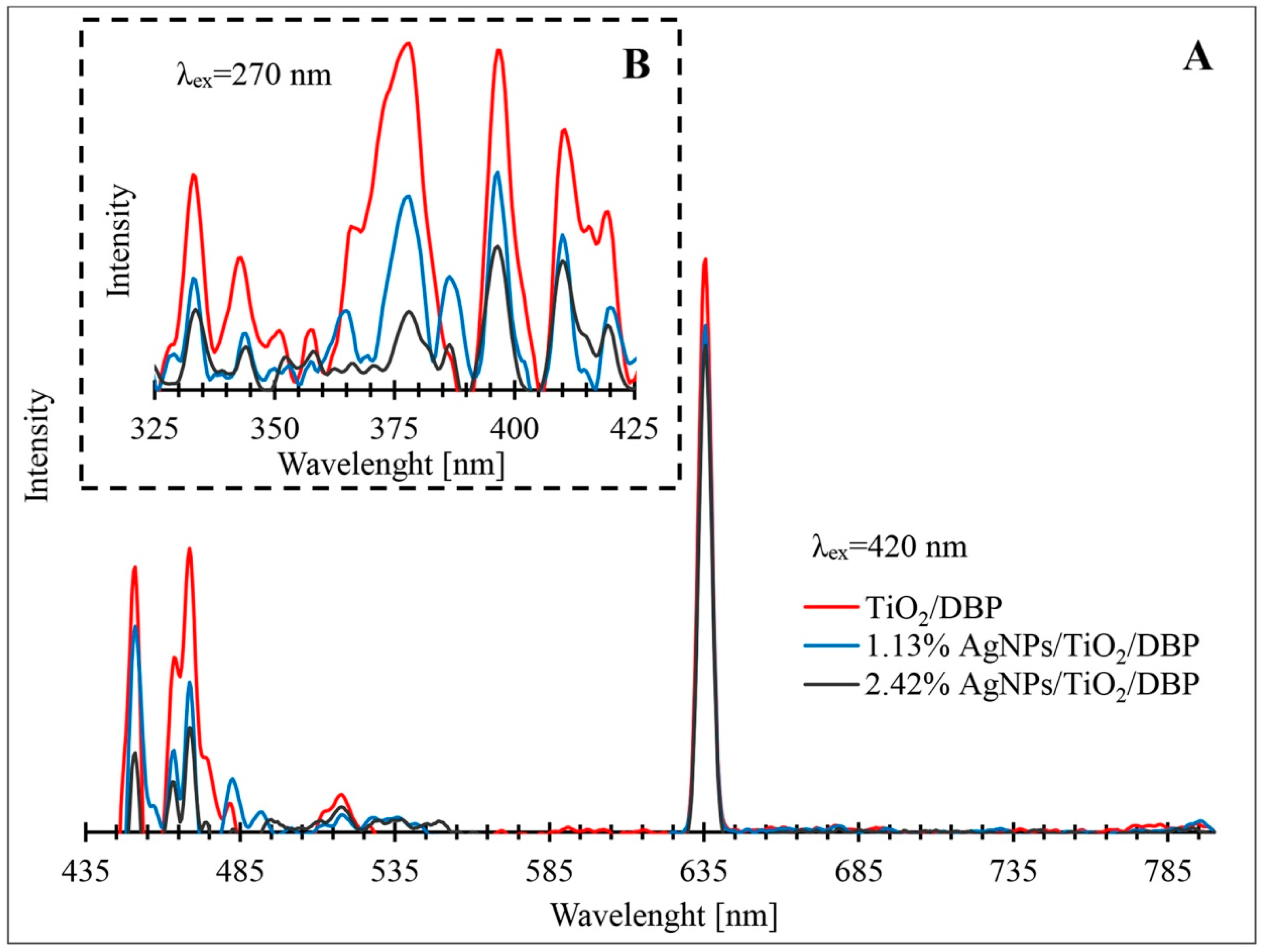

3.4. Photoluminescence Properties

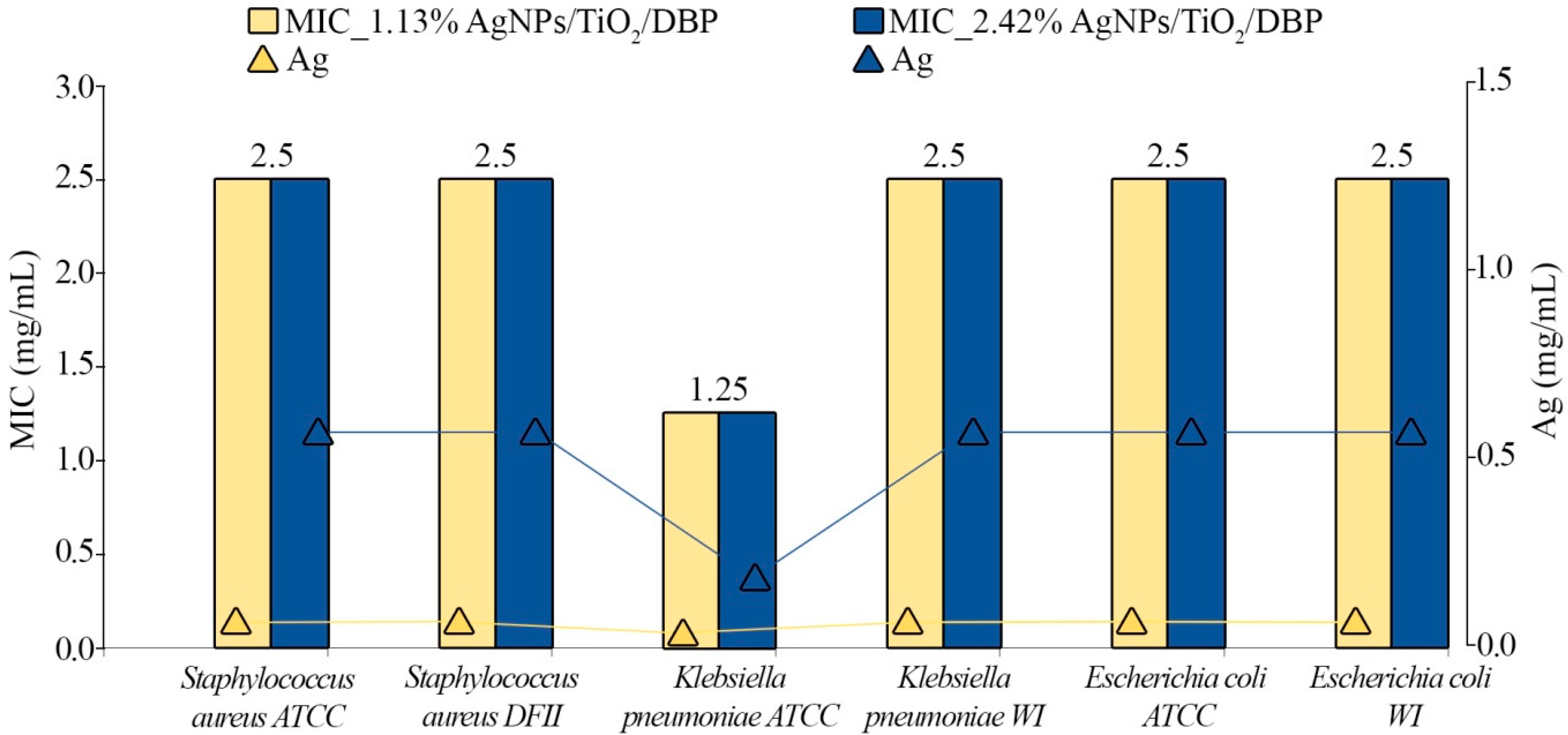

3.5. Antibacterial Activity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davies, J.; Davies, D. Origins and Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010, 74, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, C.A.; Murray, B.E. A New Antibiotic and the Evolution of Resistance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1168–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rae, M.; Carruthers, J. The future of public health. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2022, 83, 1748–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuthati, Y.; Kankala, R.K.; Lin, S.X.; Weng, C.F.; Lee, C.H. pH-Triggered Controllable Release of Silver-Indole-3 Acetic Acid Complexes from Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (IBN-4) for Effectively Killing Malignant Bacteria. Mol. Pharm. 2015, 12, 2289–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ma, L.; Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Jia, Q.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, J. Polydopamine-Encapsulated Fe3O4 with an Adsorbed HSP70 Inhibitor for Improved Photothermal Inactivation of Bacteria. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 24455–24462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, D.I.; Hughes, D. Persistence of antibiotic resistance in bacterial populations. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 35, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, T.; Ou, H.; Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Shi, L.; Liu, J. Silver-Decorated Polymeric Micelles Combined with Curcumin for Enhanced Antibacterial Activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 16880–16889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Duan, S.; Ding, X.; Liu, R.; Xu, F.-J. Versatile Antibacterial Materials: An Emerging Arsenal for Combatting Bacterial Pathogens. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1802140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Yu, Q.; Zhan, W.; Chen, H. A Smart Antibacterial Surface for the On-Demand Killing and Releasing of Bacteria. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2016, 5, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zhan, S.; Jia, Y.; Zhou, Q. Superior Antibacterial Activity of Fe3O4-TiO2 Nanosheets under Solar Light. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 21875–21883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, J.A.; Vijaya, J.J.; Kennedy, L.J.; Bououdina, M. Microwave-assisted synthesis, characterization and antibacterial properties of Ce–Cu dual doped ZnO nanostructures. Optik 2016, 127, 2360–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.A.S.; Nag, M.; Kalagara, T.; Singh, S.; Manorama, S.V. Silver on PEG-PU-TiO2 Polymer Nanocomposite Films: An Excellent System for Antibacterial Applications. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 2455–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, K.; Liu, Q.; Chen, J.; Du, J. Silver-decorated biodegradable polymer vesicles with excellent antibacterial efficacy. Polym. Chem. 2013, 5, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, W.; Chen, Z.; Sun, H.; Shi, P.; Gao, N.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Visible-light-driven enhanced antibacterial and biofilm elimination activity of graphitic carbon nitride by embedded Ag nanoparticles. Nano Res. 2015, 8, 1648–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Ouay, B.; Stellacci, F. Antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles: A surface science insight. Nano Today 2015, 10, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, M.; Serpooshan, V. Silver-Coated Engineered Magnetic Nanoparticles Are Promising for the Success in the Fight against Antibacterial Resistance Threat. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 2656–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, X.; Chu, S.; Ge, Y.; Huang, T.; Liu, Y.; Yu, L. Selenization of cotton products with NaHSe endowing the antibacterial activities. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harifi, T.; Montazer, M. Photo-, Bio-, and Magneto-active Colored Polyester Fabric with Hydrophobic/Hydrophilic and Enhanced Mechanical Properties through Synthesis of TiO2/Fe3O4/Ag Nanocomposite. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobaldi, D.M.; Piccirillo, C.; Pullar, R.C.; Gualtieri, A.F.; Seabra, M.P.; Castro, P.M.L.; Labrincha, J.A. Silver-Modified Nano-titania as an Antibacterial Agent and Photocatalyst. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 4751–4766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Wong, C.; Loredo-Becerra, G.; Quintero-González, C.; Noriega-Treviño, M.; Compeán-Jasso, M.; Niño-Martínez, N.; DeAlba-Montero, I.; Ruiz, F. Evaluation of the antibacterial activity of an indoor waterborne architectural coating containing Ag/TiO2 under different relative humidity environments. Mater. Lett. 2014, 134, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, J.; Das, B.; Chatterjee, S.; Dash, S.K.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Roy, S.; Chen, J.-W.; Chattopadhyay, T. Ag/CuO nanoparticles prepared from a novel trinuclear compound [Cu(Imdz)4(Ag(CN)2)2] (Imdz = imidazole) by a pyrolysis display excellent antimicrobial activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2016, 1113, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.H.; Manikandan, E.; Basheer Ahmed, M.; Ganesan, V. Enhanced Bioactivity of Ag/ZnO Nanorods-A Comparative Antibacterial Study. J. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. 2013, 4, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, G. Potent Antibacterial Activities of Ag/TiO2 Nanocomposite Powders Synthesized by a One-Pot Sol−Gel Method. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 2905–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajipour, M.J.; Fromm, K.M.; Ashkarran, A.A.; de Aberasturi, D.J.; de Larramendi, I.R.; Rojo, T.; Serpooshan, V.; Parak, W.J.; Mahmoudi, M. Antibacterial properties of nanoparticles. Trends Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, M.; Gavriliu, Ş.; Enescu, E.; Ion, I.; Brătulescu, A.; Mihăescu, G.; Măruţescu, L.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Silver–titanium dioxide nanocomposites as effective antimicrobial and antibiofilm agents. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2014, 16, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Tong, L.; Pan, H.; Ruan, C.; Ma, Q.; Liu, M.; Yang, H.; Zhang, L.; et al. Antibacterial effects and biocompatibility of titanium surfaces with graded silver incorporation in titania nanotubes. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 4255–4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.-C.; Wu, K.-H.; Huang, J.-W.; Horng, D.-N.; Liang, C.-F.; Hu, M.-K. Preparation and characterization of functional fabrics from bamboo charcoal/silver and titanium dioxide/silver composite powders and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2012, 32, 1062–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.A.; Pazouki, M.; Hosseinnia, A. Synthesis of TiO2–Ag nanocomposite with sol–gel method and investigation of its antibacterial activity against E. coli. Powder Technol. 2009, 196, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, G.; Vary, P.S.; Lin, C.-T. Anatase TiO2 Nanocomposites for Antimicrobial Coatings. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 8889–8898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Noriega-Trevino, M.E.; Nino-Martinez, N.; Marambio-Jones, C.; Wang, J.; Damoiseaux, R.; Ruiz, F.; Hoek, E.M.V. Synergistic Bactericidal Activity of Ag-TiO2 Nanoparticles in Both Light and Dark Conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 8989–8995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, J.; Pakstis, L.; Buzby, S.; Raffi, M.; Ni, C.; Pochan, D.J.; Shah, S.I. Antibacterial Properties of Silver-Doped Titania. Small 2007, 3, 799–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-S.; Wang, K.-X.; Li, G.-D.; Sun, S.-Y.; Sun, J.; Chen, J.-S. Montmorillonite-Supported Ag/TiO2 Nanoparticles: An Efficient Visible-Light Bacteria Photodegradation Material. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2010, 2, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Gu, J.; Liu, Q.; Tan, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, W.; Su, Y.; Li, W.; Cui, A.; Gu, C.; et al. Metal-Organic Frameworks Reactivate Deceased Diatoms to be Efficient CO2Absorbents. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 1229–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprynskyy, M.; Pomastowski, P.; Hornowska, M.; Król, A.; Rafińska, K.; Buszewski, B. Naturally organic functionalized 3D biosilica from diatom microalgae. Mater. Des. 2017, 132, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawawaki, T.; Kataoka, Y.; Hirata, M.; Akinaga, Y.; Takahata, R.; Wakamatsu, K.; Fujiki, Y.; Kataoka, M.; Kikkawa, S.; Alotabi, A.S.; et al. Inside Cover: Creation of High-Performance Heterogeneous Photocatalysts by Controlling Ligand Desorption and Particle Size of Gold Nanocluster (Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39/2021). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 21074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townley, H.E.; Parker, A.R.; White-Cooper, H. Exploitation of Diatom Frustules for Nanotechnology: Tethering Active Biomolecules. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008, 18, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aw, M.S.; Bariana, M.; Yu, Y.; Addai-Mensah, J.; Losic, D. Surface-functionalized diatom microcapsules for drug delivery of water-insoluble drugs. J. Biomater. Appl. 2013, 28, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicco, S.R.; Vona, D.; De Giglio, E.; Cometa, S.; Mattioli-Belmonte, M.; Palumbo, F.; Ragni, R.; Farinola, G.M. Chemically Modified Diatoms Biosilica for Bone Cell Growth with Combined Drug-Delivery and Antioxidant Properties. Chempluschem 2015, 80, 1104–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, A.P.; Sprynskyy, M.; Wojtczak, I.; Trzciński, K.; Wysocka, J.; Szkoda, M.; Buszewski, B.; Lisowska-Oleksiak, A. Diatoms Biomass as a Joint Source of Biosilica and Carbon for Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes. Materials 2020, 13, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, B.; Mahalingam, S. Ag/TiO2/bentonite nanocomposite for biological applications: Synthesis, characterization, antibacterial and cytotoxic investigations. Adv. Powder Technol. 2017, 28, 2265–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, R.; Uesugi, M.; Komatsu, Y.; Okamoto, F.; Tanaka, T.; Kitawaki, F.; Yano, T.-A. Highly Stable Polymer Coating on Silver Nanoparticles for Efficient Plasmonic Enhancement of Fluorescence. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 4286–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gontijo, L.A.P.; Raphael, E.; Ferrari, D.P.S.; Ferrari, J.L.; Lyon, J.P.; Schiavon, M.A. pH effect on the synthesis of different size silver nanoparticles evaluated by DLS and their size-dependent antimicrobial activity. Rev. Mater. 2020, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Qiao, X.; Qiu, X.; Chen, J. Preparation and Characterization of Nano-silver Loaded Montmorillonite with Strong Antibacterial Activity and Slow Release Property. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2011, 27, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakovan, J. Word of the wise: Hemimorphism. Rocks Miner. 2007, 82, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, U.W. Epitaxy of Semiconductors: Introduction to Physical Principles; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, T.; Jiang, L.; Wang, N.; Sun, D.; Zhao, X.; Wang, M.; Qi, Y. Nanoscale characterization of the doped SrZrO3 nanoparticles distribution and its influence on the microstructure of Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ film. J. Alloy. Compd. 2021, 858, 157650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Hu, H.; Utama, M.I.B.; Wong, L.M.; Ghosh, K.; Chen, R.; Wang, S.; Shen, Z.; Xiong, Q. Heteroepitaxial Decoration of Ag Nanoparticles on Si Nanowires: A Case Study on Raman Scattering and Mapping. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 3940–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Wong, J.C.; Weyland, M.; Valanoor, N. Encapsulation of Metal Oxide Nanoparticles by Oxide Supports during Epitaxial Growth. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2019, 1, 1482–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.S.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, X.; Cong, C.; Xie, H.; Liu, X.; Zhou, X.; Huang, F.; et al. Silane-catalysed fast growth of large single-crystalline graphene on hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, L.; Cozzoli, P.D. Colloidal heterostructured nanocrystals: Synthesis and growth mechanisms. Nano Today 2010, 5, 449–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozawa, J.; Uda, S.; Niinomi, H.; Okada, J.; Fujiwara, K. Heteroepitaxial Growth of Colloidal Crystals: Dependence of the Growth Mode on the Interparticle Interactions and Lattice Spacing. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 6995–7000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Xu, B.; Wang, G.; Miao, Y.; Li, B.; Kong, Z.; Dong, Y.; Wang, W.; Radamson, H.H. Review of Highly Mismatched III-V Heteroepitaxy Growth on (001) Silicon. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Tsai, H.-L.; Huang, C.-L. Effect of brookite phase on the anatase–rutile transition in titania nanoparticles. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2003, 23, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pighini, C.; Aymes, D.; Millot, N.; Saviot, L. Low-frequency Raman characterization of size-controlled anatase TiO2 nanopowders prepared by continuous hydrothermal syntheses. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2007, 9, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Banfield, J.F. Understanding Polymorphic Phase Transformation Behavior during Growth of Nanocrystalline Aggregates: Insights from TiO2. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 3481–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitriev, V.P.; Tolédano, P. Theory of reconstructive phase transitions between polymorphs. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter. Mater. Phys. 1998, 58, 11911–11921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammer, M.; Hedrich, R.; Ehrlich, H.; Popp, J.; Brunner, E.; Krafft, C. Spatially resolved determination of the structure and composition of diatom cell walls by Raman and FTIR imaging. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 398, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Tommasi, E. Light Manipulation by Single Cells: The Case of Diatoms. J. Spectrosc. 2016, 2016, 2490128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daude, N.; Gout, C.; Jouanin, C. Electronic band structure of titanium dioxide. Phys. Rev. B 1977, 15, 3229–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpone, N.; Lawless, D.; Khairutdinov, R. Size Effects on the Photophysical Properties of Colloidal Anatase TiO2 Particles: Size Quantization or direct transitions in this indirect semiconductor? J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 16646–16654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Zhang, L.D.; Meng, G.W.; Li, G.H.; Zhang, X.Y.; Liang, C.H.; Chen, W.; Wang, S.X. Preparation and photoluminescence of highly ordered TiO2 nanowire arrays. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2001, 78, 1125–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Berger, H.; Schmid, P.; Lévy, F.; Burri, G. Photoluminescence in TiO2 anatase single crystals. Solid State Commun. 1993, 87, 847–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraf, L.V.; Patil, S.I.; Ogale, S.B.; Sainkar, S.R.; Kshirsager, S.T. Synthesis of Nanophase TiO2 by Ion Beam Sputtering and Cold Condensation Technique. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 1998, 12, 2635–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parang, Z.; Keshavarz, A.; Farahi, S.; Elahi, S.M.; Ghoranneviss, M.; Parhoodeh, S. Fluorescence emission spectra of silver and silver/cobalt nanoparticles. Sci. Iran. 2012, 19, 943–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, B. Tailoring luminescence properties of TiO2 nanoparticles by Mn doping. J. Lumin. 2013, 136, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, J.; Sedhain, A.; Lin, J.; Jiang, H. Structure and Photoluminescence Study of TiO2 Nanoneedle Texture along Vertically Aligned Carbon Nanofiber Arrays. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 17127–17132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, D.K.; Jeffryes, C.; Gutu, T.; Jiao, J.; Chang, C.-H.; Rorrer, G.L. Thermal annealing activates amplified photoluminescence of germanium metabolically doped in diatom biosilica. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 10658–10665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, C.; Tanimura, K.; Itoh, N. Optical studies of self-trapped excitons in SiO2. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1988, 21, 4693–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.M.P.; Tavares, M.T.S.; Neto, N.F.A.; Nascimento, R.M.; Paskocimas, C.A.; Longo, E.; Bomio, M.R.D.; Motta, F.V. Photocatalytic activity and photoluminescence properties of TiO2, In2O3, TiO2/In2O3 thin films multilayer. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 6530–6542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komaraiah, D.; Radha, E.; Sivakumar, J.; Reddy, M.R.; Sayanna, R. Photoluminescence and photocatalytic activity of spin coated Ag+ doped anatase TiO2 thin films. Opt. Mater. 2020, 108, 110401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, S.; Poulose, E.K. Silver nanoparticles: Mechanism of antimicrobial action, synthesis, medical applications, and toxicity effects. Int. Nano Lett. 2012, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attallah, N.G.M.; Elekhnawy, E.; Negm, W.A.; Hussein, I.A.; Mokhtar, F.A.; Al-Fakhrany, O.M. In Vivo and In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity of Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles against Staphylococcus aureus Clinical Isolates. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, I.-L.; Hsieh, Y.-K.; Wang, C.-F.; Chen, I.-C.; Huang, Y.-J. Trojan-Horse Mechanism in the Cellular Uptake of Silver Nanoparticles Verified by Direct Intra- and Extracellular Silver Speciation Analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 3813–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.; Kim, H.-K.; Wamer, W.G.; Melka, D.; Callahan, J.H.; Yin, J.-J. Photogenerated Charge Carriers and Reactive Oxygen Species in ZnO/Au Hybrid Nanostructures with Enhanced Photocatalytic and Antibacterial Activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.S.D.; Rajendran, N.K.; Houreld, N.N.; Abrahamse, H. Recent advances on silver nanoparticle and biopolymer-based biomaterials for wound healing applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 115, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanmani, P.; Rhim, J.-W. Physical, mechanical and antimicrobial properties of gelatin based active nanocomposite films containing AgNPs and nanoclay. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 35, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Núñez, N.V.; Villegas, H.H.L.; Del Carmen Ixtepan Turrent, L.; Padilla, C.R. Silver Nanoparticles Toxicity and Bactericidal Effect Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Nanoscale Does Matter. Nanobiotechnology 2009, 5, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.A.; El Maghraby, G.M.; Sonbol, F.I.; Allam, N.G.; Ateya, P.S.; Ali, S.S. Enhanced Efficacy of Some Antibiotics in Presence of Silver Nanoparticles Against Multidrug Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Recovered From Burn Wound Infections. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladini, F.; Pollini, M. Antimicrobial Silver Nanoparticles for Wound Healing Application: Progress and Future Trends. Materials 2019, 12, 2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wali, N.; Shabbir, A.; Wajid, N.; Abbas, N.; Naqvi, S.Z.H. Synergistic efficacy of colistin and silver nanoparticles impregnated human amniotic membrane in a burn wound infected rat model. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, S.; Allafchian, A.; Banifatemi, S.; Tamai, I.A. The antibacterial properties of Ag/TiO2 nanoparticles embedded in silane sol–gel matrix. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 66, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekissanova, Z.; Railean, V.; Brzozowska, W.; Wojtczak, I.; Ospanova, A.; Buszewski, B.; Sprynskyy, M. Synthesis, characterization of silver/kaolinite nanocomposite and studying its antibacterial activity. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 220, 112908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CMITC | ATCC |

|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC33591 THL (DFI), Klebsiella pneumoniae 9295_1 CHB (WI), Escherichia coli MB 11464 1 CHB (WI)) | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 700699, Klebsiella pneumonia ATCC 10031, Escherichia coli ATCC 10031 |

| Bacteria Strains | Minimal Inhibitory Concentration of AgNPs/TiO2/DBP [mg/mL] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2/DBP | 1.13% AgNPs/TiO2/DBP | 2.42% AgNPs/TiO2/DBP | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | ATCC | - | 2.5 (0.0283 Ag mg/mL) | 2.5 (0.0605 Ag mg/mL) |

| DFII | - | 2.5 (0.0283 Ag mg/mL) | 2.5 (0.0605 Ag mg/mL) | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | ATCC | - | 1.25 (0.0142 Ag mg/mL) | 1.25 (0.0303 Ag mg/mL) |

| WI | - | 2.5 (0.0283 Ag mg/mL) | 2.5 (0.0605 Ag mg/mL) | |

| Escherichia coli | ATCC | - | 2.5 (0.0283 Ag mg/mL) | 2.5 (0.0605 Ag mg/mL) |

| WI | - | 2.5 (0.0283 Ag mg/mL) | 2.5 (0.0605 Ag mg/mL) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brzozowska, W.; Wojtczak, I.; Railean, V.; Bekissanova, Z.; Trykowski, G.; Buszewski, B.; Sprynskyy, M. Pyrolized Diatomaceous Biomass Doped with Epitaxially Growing Hybrid Ag/TiO2 Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterisation and Antibacterial Application. Materials 2023, 16, 4345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16124345

Brzozowska W, Wojtczak I, Railean V, Bekissanova Z, Trykowski G, Buszewski B, Sprynskyy M. Pyrolized Diatomaceous Biomass Doped with Epitaxially Growing Hybrid Ag/TiO2 Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterisation and Antibacterial Application. Materials. 2023; 16(12):4345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16124345

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrzozowska, Weronika, Izabela Wojtczak, Viorica Railean, Zhanar Bekissanova, Grzegorz Trykowski, Bogusław Buszewski, and Myroslav Sprynskyy. 2023. "Pyrolized Diatomaceous Biomass Doped with Epitaxially Growing Hybrid Ag/TiO2 Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterisation and Antibacterial Application" Materials 16, no. 12: 4345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16124345

APA StyleBrzozowska, W., Wojtczak, I., Railean, V., Bekissanova, Z., Trykowski, G., Buszewski, B., & Sprynskyy, M. (2023). Pyrolized Diatomaceous Biomass Doped with Epitaxially Growing Hybrid Ag/TiO2 Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterisation and Antibacterial Application. Materials, 16(12), 4345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16124345