Structure and Magnetic Properties of SrFe12−xInxO19 Compounds for Magnetic Hyperthermia Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

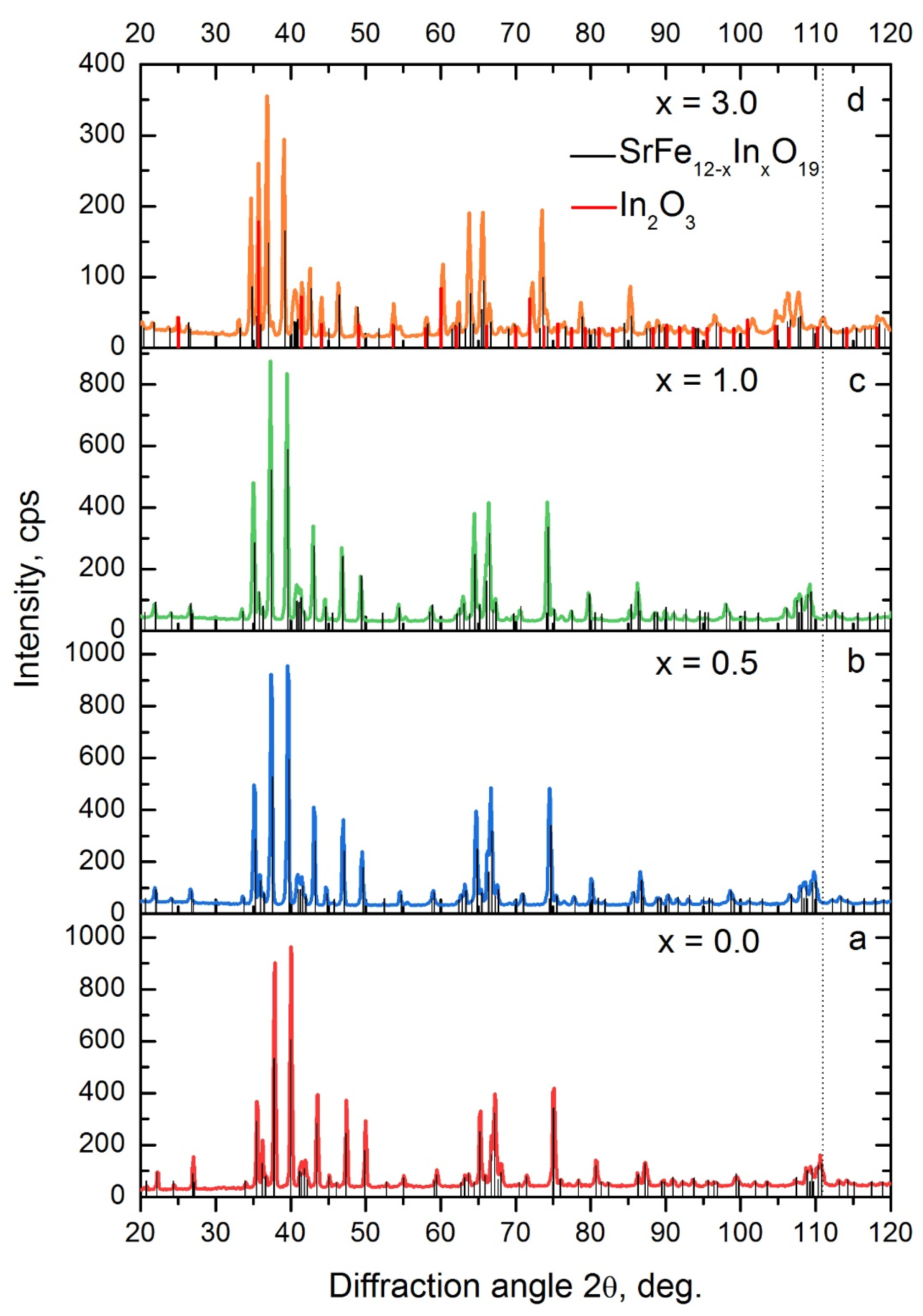

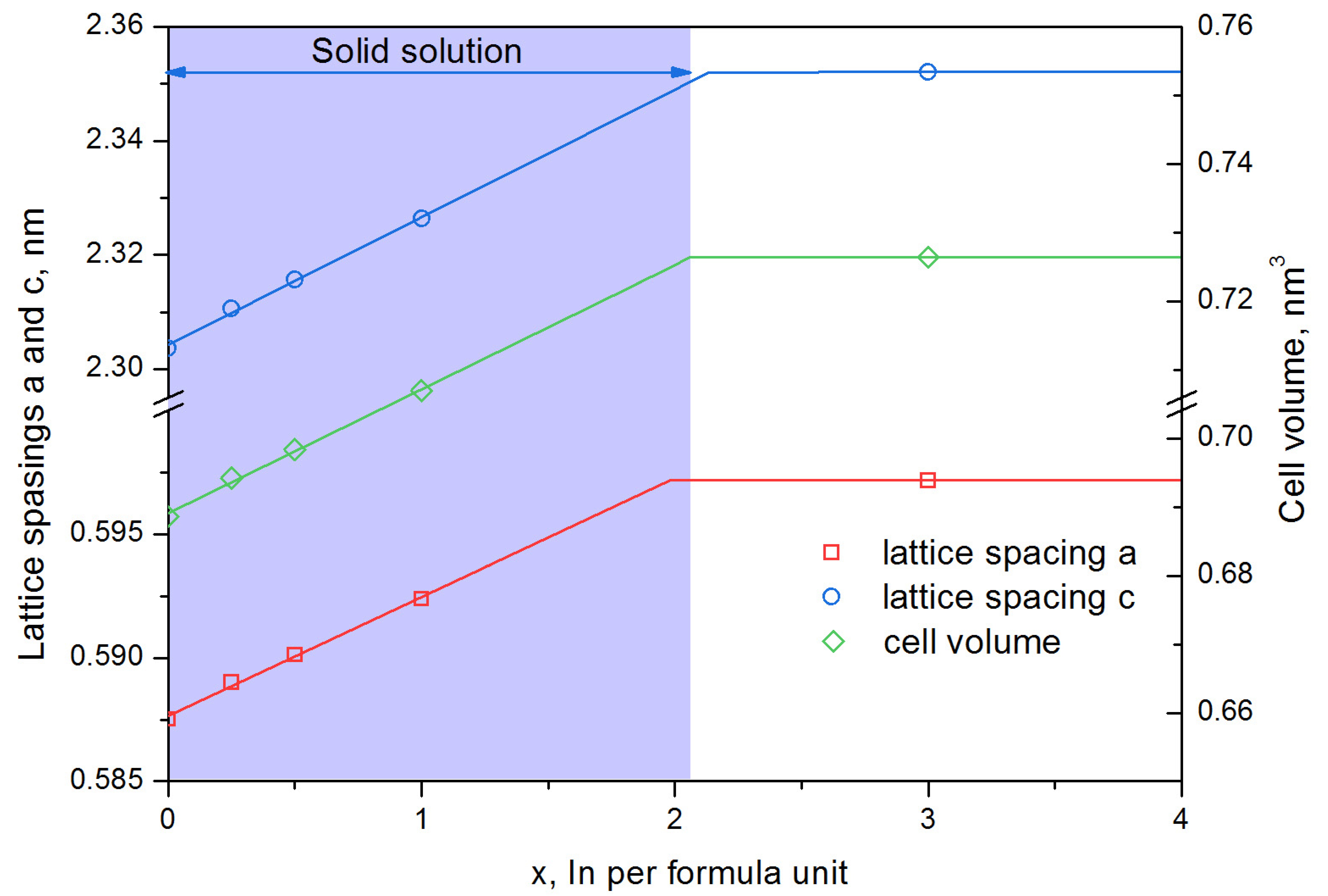

- The solubility limit of In in hexaferrite SrFe12O19 at 1200 °C was determined—it reaches to x = 2.1 In atoms per hexaferrite formula unit. According to Mössbauer spectroscopy data, In predominantly occupies the 12k positions;

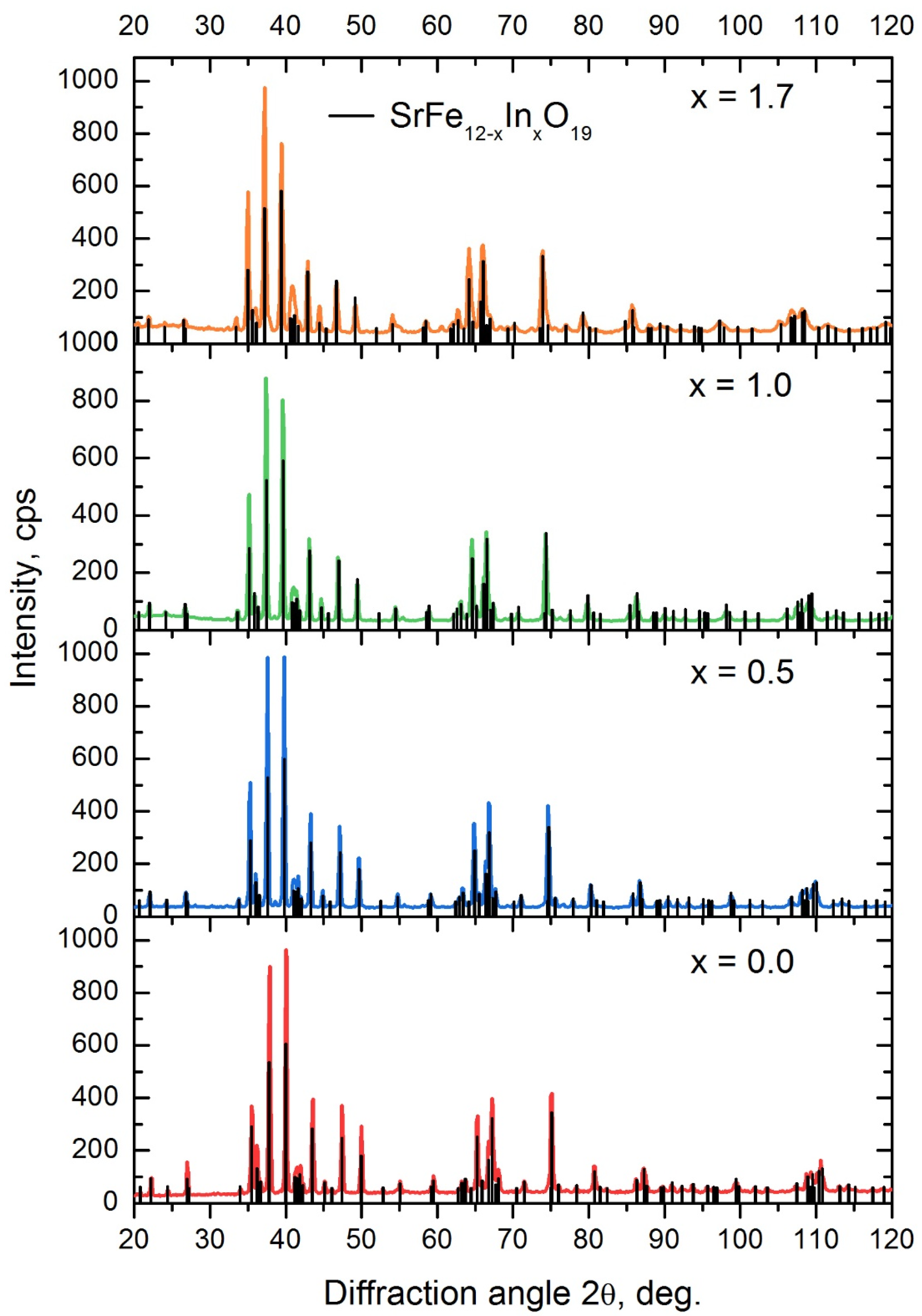

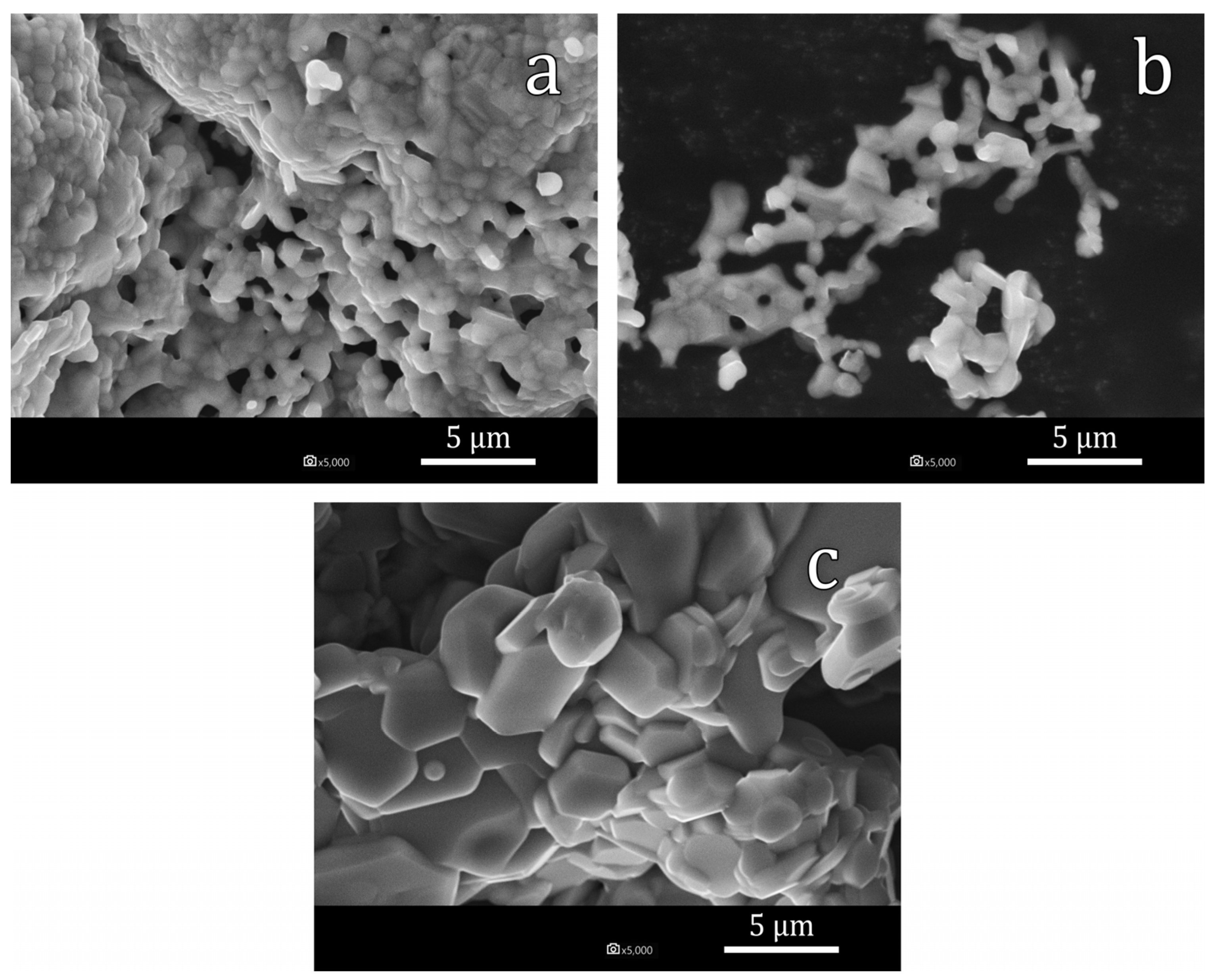

- Using the citrate method and subsequent annealing at 1200 °C, the SrFe12−xInxO19 powders with x = 0.5, x = 1.0 and x = 1.7 were obtained. All synthesized samples contained at least 97% of the SrFe12−xInxO19 phase. Sample particles had sizes in the range of 0.5–5 µm and were collected in agglomerates. As the degree of doping increases, an increase in the average particle size is observed;

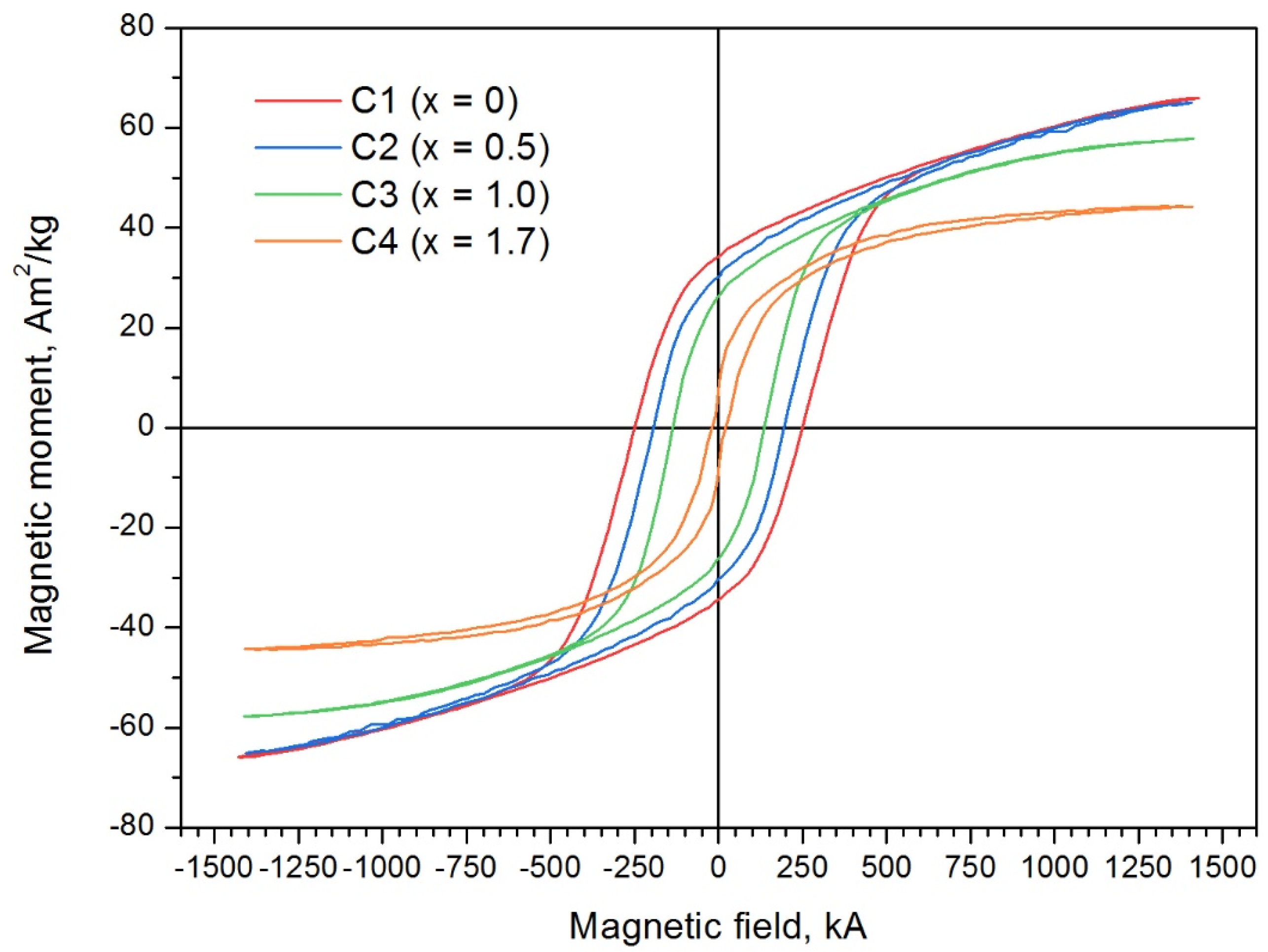

- As the degree of substitution of iron by indium increases from x = 0.5 to x = 1.7, the coercivity of the samples strongly decreases from 188.9 kA/m to 22.3 kA/m. The specific magnetization decreases from 63.5 A·m2/kg to 44.2 A·m2/kg;

- SrFe12−xInxO19 sample with x = 1.7 experienced evident heating when introduced into an alternating magnetic field. The best results of magnetic hyperthermia of the sample were observed at a field strength of 19.94 kA/m and a frequency of 261 kHz (at a high sample concentration (56.67 g/L), heating from 23 to 41 °C was achieved in 2 min).

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Went, J.J.; Rathenau, G.W.; Gorter, E.W.; van Oosterhout, G.W. Ferroxdure, a class of new permanent magnet materials. Philips Tech. Rew. 1951, 13, 194–208. [Google Scholar]

- Pullar, R.C. Hexagonal ferrites: A review of the synthesis, properties and applications of hexaferrite ceramics. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2012, 57, 1191–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, G.; Anis-ur-Rehman, M. Structural, dielectric and magnetic properties of Cr–Zn doped strontium hexa-ferrites for high frequency applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2012, 526, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Shaukat, S.F.; Haidyrah, A.S.; Akhtar, M.N.; Ahmad, M. Synthesis and investigations of structural, magnetic and dielectric properties of Cr-substituted W-type Hexaferrites for high frequency applications. J. Electroceram. 2021, 46, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashiq, M.N.; Iqbal, M.J.; Najam-ul-Haqa, M.; Gomez, P.H.; Qureshi, A.M. Synthesis, magnetic and dielectric properties of Er–Ni doped Sr-hexaferrite nanomaterials for applications in High density recording media and microwave devices. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2012, 324, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsch, K.; Wehrspohn, R.B.; Barthel, J.; Kirschner, J.; Fischer, S.F.; Kronmüller, H.; Schweinböck, T.; Weiss, D.; Gösele, U. High density hexagonal nickel nanowire array. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2002, 249, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferk, G.; Krajnc, P.; Hamler, A.; Mertelj, A.; Cebollada, F.; Drofenik, M.; Lisjak, D. Monolithic Magneto-Optical Nanocomposites of Barium Hexaferrite Platelets in PMMA. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auwal, I.A.; Baykal, A.; Güner, S.; Sertkol, M.; Sözeri, H. Magneto-optical properties BaBixLaxFe12−2xO19 (0.0≤x≤0.5) hexaferrites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2016, 409, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, A.D.M.; Rider, A.N.; Brown, S.A.; Wang, C.H. Multifunctional magneto-polymer matrix composites for electromagnetic interference suppression, sensors and actuators. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 115, 100705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, M.A.; Afifi, A.I.; Abd El-Hameed, A.S.; Abosheiasha, H.F.; Henaish, A.M.A.; Salogub, D.; Morchenko, A.T.; Kostishyn, V.G.; Turchenko, V.A.; Trukhanov, A.V. Can hexaferrite composites be used as a new artificial material for antenna applications? Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icin, K.; Ozturk, S.; Cakil, D.D.; Sunbul, S.E. Effect of the stoichiometric ratio on phase evolution and magnetic properties of SrFe12O19 produced with mechanochemical process using mill scale. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 14150–14160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketov, S.V.; Yagodkun, Y.D.; Lebed, A.L.; Chernopyatova, Y.V.; Khlopkov, K. Structure and magnetic properties of nanocrystalline SrFe12O19 alloy produced by high-energy ball milling and annealing. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2006, 300, e479–e481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wu, C.; Qi, B.; Zhang, H. Microstructure and magnetic properties of Y substituted M-type hexaferrite BaYxFe12−xO19. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 5911–5916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi, Z.F.; Sun, Y.P.; Zhu, X.B.; Yang, Z.R.; Dai, J.M.; Song, W.H. Structural and magnetic properties of SrFe12O19 hexaferrite synthesized by a modified chemical co-precipitation method. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2008, 320, 2746–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessien, M.M.; Rashad, M.M.; El-Barawy, K. Controlling the composition and magnetic properties of strontium hexaferrite synthesized by co-precipitation method. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2008, 320, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matutes-Aquino, J.; Díaz-Castanon, S.; Mirabal-Garcıa, M.; Palomares-Sanchez, S.A. Synthesis by coprecipitation and study of barium hexaferrite powders. Scr. Mater. 2000, 42, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, D.D.; Kushnir, S.E.; Kazin, P.E.; Tretyakov, Y.D.; Jansen, M. Preparation of the SrFe12O19-based magnetic composites via boron oxide glass devitrification. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2006, 301, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anokhin, E.O.; Trusov, L.A.; Kozlov, D.A.; Chumakov, R.G.; Sleptsova, A.E.; Uvarov, O.V.; Kozlov, M.I.; Petukhov, D.I.; Eliseev, A.A.; Kazin, P.E. Silica coated hard-magnetic strontium hexaferrite nanoparticles. Adv. Powder Technol. 2019, 30, 1976–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, M.; Nachbaur, V.; Bran, J.; Le Breton, J.-M. Synthesis and characterization of SrFe12O19 powder obtained by hydrothermal process. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 496, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikeland, A.Z.; Holscher, J.; Christensen, M. Hydrothermal synthesis of SrFe12O19 nanoparticles: Effect of the choice of base and base concentration. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2021, 54, 134004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Jia, L.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, H. Hydrothermal synthesis and competitive growth of flake-like M-type strontium hexaferrite. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 33388–33394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, T.-S.; Hsu, S.L.; Deng, M.C. Barium ferrite particulates prepared by a salt-melt method. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1993, 120, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikeland, A.Z.; Stingaciu, M.; Mamakhel, A.H.; Saura-Muzquiz, M.; Christensen, M. Enhancement of magnetic properties through morphology control of SrFe12O19 nanocrystallites. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirkazemi, S.; Alamolhoda, S.; Ghiami, Z. Microstructure and Magnetic Properties of SrFe12O19 Nano-sized Powders Prepared by Sol-Gel Auto-combustion Method with CTAB Surfactant. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2015, 28, 1543–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, A.; Fedorova, M.; Naumenko, V.; Schetinin, I.; Abakumov, M.; Erofeev, A.; Gorelkin, P.; Meshkov, G.; Beloglazkina, E.; Ivanenkov, Y. Synthesis, characterization and MRI application of magnetite water-soluble cubic nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 441, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, A.A.; Fedorova, N.D.; Tabachkova, N.Y.; Schetinin, I.V.; Abakumov, M.A.; Soldatov, M.V.; Soldatov, A.V.; Beloglazkina, E.K.; Sviridenkova, N.V. Synthesis of Iron Oxide Nanoclusters by Thermal Decomposition. Langmuir 2018, 34, 4640–4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metelkina, O.N.; Lodge, R.W.; Rudakovskaya, P.G.; Gerasimov, V.M.; Lucas, C.H.; Grebennikov, I.S.; Shchetinin, I.V.; Savchenko, A.G.; Pavlovskaya, G.E.; Rance, G.A. Nanoscale engineering of hybrid magnetite–carbon nanofibre materials for magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 2167–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, A.; Khramtsov, M.; Garanina, A.; Mogilnikov, P.; Sviridenkova, N.; Shchetinin, I.; Savchenko, A.; Abakumov, A.; Majouga, A. Synthesis of iron oxide nanorods for enhanced magnetic hyperthermia. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 469, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.; Wilhelm, C.; Siaugue, J.M. Magnetically induced hyperthermia: Size-dependent heating power of γ -Fe2O3 nanoparticles. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2008, 20, 204133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangijzegem, T.; Stanicki, D.; Laurent, S. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for drug delivery: Applications and characteristics. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2019, 16, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Huo, D.; Tan, W. Room-temperature magnetoresistive and magnetocaloric effect in La1−xBaxMnO3 compounds: Role of Griffiths phase with ferromagnetic metal cluster above Curie temperature. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 131, 043901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertug, B. Investigation of Ferrimagnetic Sr-hexaferrite Nanocrystals for Clinical Hyperthermia. Mater. Sci. Medzg. 2021, 27, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Yu, B.; Yangyang, T.; Di, L.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J. Recent Advances in Nanoplatforms for the Treatment of Osteosarcoma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 805978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Gorsak, T.; Rodriguez, E.M.; Calle, D.; Munoz-Ortiz, T. Magnetic Nanoplatelets for High Contrast Cardiovascular Imaging by Magnetically Modulated Optical Coherence Tomography. ChemPhotoChem 2019, 3, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsak, T.; Drab, M.; Krizaj, D.; Jeran, M.; Genova, J.; Kralj, S.; Lisjak, D. Magneto-mechanical actuation of barium-hexaferrite nanoplatelets for the disruption of phospholipid membranes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 579, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vershinina, S.F.; Evtushenko, V.I. The effect of intratumor implantation of barium hexaferrite, magnetite, hematite, aluminum oxide and silica on the growth dynamics of Ehrlich’s tumor and the survival rate of tumor-bearing mice. Med. Acad. J. 2020, 20, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trusov, L.; Vasiliev, A.; Lukatskaya, M. Stable colloidal solutions of strontium hexaferrite hard magnetic nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 14581–14584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushnir, S.E.; Gavrilov, A.I.; Kazin, P.E. Synthesis of colloidal solutions of SrFe12O19 plate-like nanoparticles featuring extraordinary magnetic-field-dependent optical transmission. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 18893–18901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, W.J.; Brezovich, I.A.; Chakraborty, D.P. Usable frequencies in hyperthermia with thermal seeds. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1984, 1, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafinezhad, A.; Abdellahi, M.; Saber-Samandari, S. Hydroxyapatite—M-type strontium hexaferrite: A new composite for hyperthermia applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 734, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trukhanov, S.V.; Trukhanov, A.V.; Turchenko, V.A.; Trukhanov, A.V.; Trukhanova, E.L.; Tishkevich, D.I.; Panina, L.V. Polarization origin and iron positions in indium doped barium hexaferrites. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchenko, V.A.; Trukhanov, S.V.; Kostishin, V.G.; Damay, F.; Porcher, F.; Klygach, D.S.; Vakhitov, M.G.; Lyakhov, D.; Michels, D.; Bozzo, B.; et al. Features of structure, magnetic state and electrodynamic performance of SrFe12−xInxO19. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Yang, Y.; Lei, R.-Y.; Zhou, J.-P.; Chen, X.-M. The effects of indium doping on the electrical, magnetic, and magnetodielectric properties of M-type strontium hexaferrites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2021, 539, 168333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trusov, L.A.; Gorbachev, E.A.; Lebedev, V.A.; Sleptsova, A.E.; Roslyakov, I.V.; Jansen, M.; Kazin, P.E. Ca–Al double-substituted strontium hexaferrites with giant coercivity. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 479–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemine, O.M.; Madkhali, M.; Hjiri, M.; Aida, M.S. Comparative heating efficiency of hematite (α-Fe2O3) and nickel ferrite nanoparticles for magnetic hyperthermia application. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 28821–28827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nasir, M.H.; Siddique, S.; Aisida, S.O.; Altowairqi, Y.; Fadhali, M.M.; Shariq, M.; Khan, M.S.; Qamar, M.A.; Shahid, T.; Shahzad, M.I.; et al. Structural, Magnetic, and Magnetothermal Properties of Co100−xNix Nanoparticles for Self-Controlled Hyperthermia. Coatings 2022, 12, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| x, at. in per Formula Unit | Phase Composition, % (±3) | Phase SrFe12−xInxO19 Parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a, nm (±0.0001) | c, nm (±0.0003) | Cell Volume, nm3 (±0.003) | c/a Ratio (±0.001) | ||

| 0 | SrFe12O19—100% | 0.5875 | 2.3036 | 0.6886 | 3.921 |

| 0.25 | SrFe12−xO19—100% | 0.589 | 2.3106 | 0.6942 | 3.923 |

| 0.5 | SrFe12−xO19—100% | 0.5901 | 2.3157 | 0.6984 | 3.924 |

| 1.0 | SrFe12−xO19—100% | 0.5924 | 2.3263 | 0.7070 | 3.927 |

| 3 | SrFe12−xO19—83% In2O3—17% | 0.5972 | 2.352 | 0.7264 | 3.939 |

| Hyperfine Parameters of Mössbauer Spectra | Sample | Fe Site | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12k | 12k’ | 4f1 | 4f2 | 2a | 2b | ||

| Hyperfine magnetic field Hhf, kOe | x = 0 | 409 | - | 488 | 515 | 505 | 406 |

| x = 0.5 | 403 | 341 | 484 | 494 | 488 | 378 | |

| x = 1.0 | 394 | 330 | 461 | 474 | 455 | 355 | |

| Isomer shift (IS), mm/s | x = 0 | 0.35 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.29 | |

| x = 0.5 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.35 | |

| x = 1.0 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.24 | |

| Quadrupole splitting (QS), mm/s | x = 0 | 0.40 | - | 0.17 | 0.29 | 0.02 | 2.2 |

| x = 0.5 | 0.39 | 0.37 | 0.11 | 0.39 | 0.08 | 2.2 | |

| x = 1.0 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.02 | 2.4 | |

| Relative intensity, % | x = 0 | 48 | - | 19 | 18 | 9 | 6 |

| x = 0.5 | 35 | 14 | 18 | 20 | 7 | 6 | |

| x = 1.0 | 26 | 24 | 21 | 15 | 8 | 6 | |

| Sample | x, at. in per Formula Unit (Estimated) | Phase Composition, % | Phase SrFe12−xInxO19 Parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a, nm (±0.0001) | c, nm (±0.0003) | Cell Volume, nm3 (±0.03) | c/a Ratio (±0.001) | |||

| C1 | 0 | SrFe12O19—100% | 0.5876 | 2.3034 | 0.6888 | 3.920 |

| C2 | 0.5 | SrFe12O19—100% | 0.5903 | 2.3144 | 0.6984 | 3.921 |

| C3 | 1.0 | SrFe12O19—99.5% Fe2O3—0.5% | 0.5926 | 2.3264 | 0.7075 | 3.926 |

| C4 | 1.7 | SrFe12O19—98% In2O3—2% | 0.5955 | 2.343 | 0.7196 | 3.935 |

| Sample | x, at. in per Formula Unit (Estimated Quantity) | Coercitivity Force Hc, kA/m | Remanence Magnetization σr, A·m2/kg | Saturation Magnetization σs, A·m2/kg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 0 | 254.1 | 65.3 | 33.5 |

| C2 | 0.5 | 188.9 | 63.5 | 28.6 |

| C3 | 1.0 | 135.6 | 57.7 | 26.2 |

| C4 | 1.7 | 22.3 | 44.2 | 7.7 |

| Concentration, g/L | Time, s | f, kHz | H, kA/m | Tstart, °C | Tfinish, °C | SLP, W/g | ILP, (nH·m2)/kg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10.00 | 120 | 261 | 19.94 | 20 | 22 | 6.97 | 0.067 |

| 56.67 | 120 | 261 | 19.94 | 23 | 41 | 11.07 | 0.107 |

| 56.67 | 120 | 508 | 11.96 | 22 | 31 | 5.54 | 0.076 |

| 56.67 | 120 | 144 | 19.94 | 21 | 27 | 3.69 | 0.064 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nikolenko, P.I.; Nizamov, T.R.; Bordyuzhin, I.G.; Abakumov, M.A.; Baranova, Y.A.; Kovalev, A.D.; Shchetinin, I.V. Structure and Magnetic Properties of SrFe12−xInxO19 Compounds for Magnetic Hyperthermia Applications. Materials 2023, 16, 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16010347

Nikolenko PI, Nizamov TR, Bordyuzhin IG, Abakumov MA, Baranova YA, Kovalev AD, Shchetinin IV. Structure and Magnetic Properties of SrFe12−xInxO19 Compounds for Magnetic Hyperthermia Applications. Materials. 2023; 16(1):347. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16010347

Chicago/Turabian StyleNikolenko, Polina I., Timur R. Nizamov, Igor G. Bordyuzhin, Maxim A. Abakumov, Yulia A. Baranova, Alexander D. Kovalev, and Igor V. Shchetinin. 2023. "Structure and Magnetic Properties of SrFe12−xInxO19 Compounds for Magnetic Hyperthermia Applications" Materials 16, no. 1: 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16010347

APA StyleNikolenko, P. I., Nizamov, T. R., Bordyuzhin, I. G., Abakumov, M. A., Baranova, Y. A., Kovalev, A. D., & Shchetinin, I. V. (2023). Structure and Magnetic Properties of SrFe12−xInxO19 Compounds for Magnetic Hyperthermia Applications. Materials, 16(1), 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16010347